On this day on 1st March

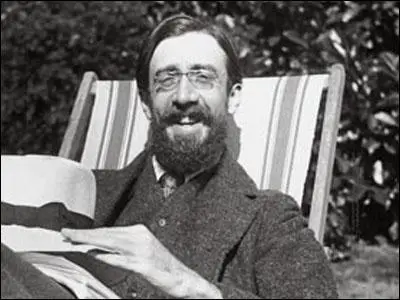

On this day in 1880 writer Lytton Strachey, the eighth of the ten surviving children of Lieutenant-General Sir Richard Strachey (1817–1908) and his wife, Jane Grant Strachey (1840–1928), was born at Stowey House, Clapham Common, on 1st March 1880. Amongst his brother and sisters were James Strachey, Oliver Strachey and Philippa Strachey.

He was educated at Abbotsholme (1893–4); Leamington College (1894–7), Liverpool University (1897–9) and Trinity College (1899–1905), where he met his life-long friends, Leonard Woolf and Clive Bell. Other friends at university included George Mallory, John Maynard Keynes, and Bertrand Russell.

While at the University of Cambridge he was elected to the famous undergraduate society known as the Apostles. Other members included E. M. Forster, Roger Fry, George Edward Moore, Robert Trevelyan, Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson and Desmond MacCarthy. According to his biographer, Stanford Patrick Rosenbaum: "With Keynes and J. T. Sheppard, Strachey turned the Apostles into more of a homosexual brotherhood than it had been. The publication of Moore's Principia ethica in 1903 marked for Strachey the beginning of a new age of reason. The book's analytic method and realistic epistemology, its fundamental distinction between instrumental and intrinsic good, its concept of organic unity, and its ideals of love and beauty all influenced Strachey's writings, beginning with the humorous Apostle papers that he wrote during his ten years as an active member."

In 1905 Lytton Strachey joined with several friends to discuss literary and artistic issues. The friends, who eventually became known as the Bloomsbury Group, included Virginia Woolf, Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell, John Maynard Keynes, E. M. Forster, Duncan Grant, Vita Sackville-West, Ottoline Morrell, Leonard Woolf, David Garnett, Roger Fry, Desmond MacCarthy and Arthur Waley.

Later that year Strachey met the artist Henry Lamb. He told his friend, Leonard Woolf: "He's run away from Manchester, became an artist, and grown side-whiskers... I didn't speak to him, but wanted to, because he really looked amazing, though of course very bad." Strachey made several unsuccessful attempts to seduce Lamb. His biographer, Michael Holroyd, has argued that Strachey was "convinced that Henry, with his angelic smile, his feminine skin and moments of incredible charm, could be converted to bisexuality".

According to Vanessa Curtis: "Lamb was an Adonis, with curly blond hair, a slim figure and a unique way of dressing in old-fashioned silk or velvet garments. He sported a gold earring and had a playful sense of humour. When he was in a good mood he proved an enchanting and alluring companion for Ottoline, but when he was depressed and bad-tempered, it took all of her natural patience and love to see them both through these difficult periods."

Strachey tried at first to earn a livelihood as a literary journalist. Between 1907 and 1909 he wrote nearly a hundred weekly reviews for The Spectator. He also contributed to Desmond MacCarthy's New Quarterly. Strachey left the magazine in 1909 in order to concentrate on his own writing. However, he continued to provide material for The Edinburgh Review.

Strachey remained in love with Henry Lamb, claimed that he was "a genius there can be no doubt, but whether a good or an evil one?" He added: "He is the most delightful companion in the world and the most unpleasant." Duncan Grant, another homosexual, got to know Lamb and told Strachey, "I'm convinced now he's a bad lot." Ottoline Morrell, who was having an affair with Lamb, also complained about his aggressive moods of depression: "The more I suffered from it the more he delighted in tormenting me."

Virginia Woolf fell in love with Strachey. However, he was having a sexual relationship with his cousin Duncan Grant. This ended painfully when Grant fell in love with John Maynard Keynes. On 25th January 1912 Lytton Strachey wrote to Ottoline Morrell: "He (Henry Lamb) has been charming, and I am much happier. I'm afraid I may have exaggerated his asperities; his affection I often feel to be miraculous. It was my sense of the value of our relationship, and my fear that it might come to an end, that made me cry out so loudly the very minute I was hurt."

Lytton Strachey met Dora Carrington while staying with Virginia Woolf at Asheham House at Beddingham, near Lewes, she jointly leased with Leonard Woolf, Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell and Duncan Grant. The author of Virginia Woolf's Women (2002) has pointed out: "Attracted to Carrington from the moment he first laid eyes on her, he had boldly tried to kiss her during a walk across the South Downs, the feeling of his beard prompting an enraged outburst of disgust from the unwilling recipient. According to legend, Carrington plotted frenzied revenge, creeping into Lytton's bedroom during the night with the intention of cutting off the detested beard. Instead, she was mesmerized by his eyes, which opened suddenly and regarded her intently. From that moment on, the two became virtually inseparable. Initially, Strachey's friends viewed the idea of Carrington and Lytton as a couple with repulsion; it was considered extremely inappropriate. Even though it was evident almost from the start that they were to enjoy a platonic relationship rather than a sexual one, the relationship was the talk of Bloomsbury for several months. They were a curious looking couple: Lytton was tall and lanky, bespectacled and with a curiously high-pitched voice, Carrington was short, chubby, eccentrically dressed and with daringly short hair."

Lytton Strachey refused to join the armed forces during the First World War. On 17th March 1916 he had appeared before the Hampstead Tribunal, accompanied by numerous friends and supporters to plead his case. This included the Liberal MP, Philip Morrell. When asked if he had a conscientious objection to all wars, he replied, "Oh no, not at all. Only this one." He was turned down for conscientious objector status but after his medical it was decided he was not fit enough for military service.

According to David Garnett: "They (Dora Carrington and Lytton Strachey) became lovers, but physical love was made difficult and became impossible. The trouble on Lytton's side was his diffidence and feeling of inadequacy, and his being perpetually attracted by young men; and on Carrington's side her intense dislike of being a woman, which gave her a feeling of inferiority so that a normal and joyful relationship was next to impossible....When sexual love became difficult each of them tried to compensate for what the other could not give in a series of love affairs."

In 1917, Strachey set up home with Dora Carrington at Mill House, Tidmarsh, in Berkshire. Carrington's close friend, Dorothy Brett, was shocked by the decision: "How and why Carrington became so devoted to him I don't know. Why she submerged her talent and whole life in him, a mystery... Gertler's hopeless love for her, most of her friendships I think were partially discarded when she devoted herself to Lytton... I know that Lytton at first was not too kind with Carrington's lack of literary knowledge. She pandered to his sex obscenities, I saw her, so I got an idea of it. I ought not to be prejudiced. I think Gertler and I could not help being prejudiced. It was so difficult to understand how she could be attracted." Mark Gertler was furious and asked Carrington how she could "love a man like Strachey twice your age (36) and emaciated and old."

Dora Carrington and Lytton Strachey did attempt a sexual relationship. She was willing to adapt to Strachey's homosexuality. However, she admitted in a letter to Strachey: "Hours were spent in front of the glass last night strapping the locks back, and trying to persuade myself that two cheeks like turnips on the top of a hoe bore some resemblance to a very well nourished youth of sixteen." Virginia Woolf assumed that Carrington was having a sexual relationship with Strachey. However, she recalled in her diary on 2nd July, 1918: "After tea Lytton and Carrington left the room ostensibly to copulate; but suspicion was aroused by a measured sound proceeding from the room, and on listening at the keyhole it was discovered that they were reading aloud Macaulay's Essays!"

In the summer of 1918, Dora's brother, Noel Carrington, introduced her to a friend, Ralph Partridge, who he had rowed with at University of Oxford, while they were on holiday in Scotland. On 4th July she wrote to Lytton Strachey that "Partridge shared all the best views of democracy and social reform... I hope I shall see him again - not very attractive to look at. Immensely big. But full of wit, and recklessness." Strachey replied: "The existence of Partridge is exciting. Will he come down here when you return? I hope so; but you give no suggestion of his appearance - except that he's immensely big - which may mean anything. And then, I have a slight fear that he may be simply a flirt."

Gretchen Gerzina, the author of A Life of Dora Carrington: 1893-1932 (1989), pointed out "Partridge was the opposite of the kind of man who normally attracted her. He was tall and broad-shouldered and, in spite of her critical assessment of his looks, very handsome. He was in many ways a man's man, who wore his uniform as if he was meant to and was an athlete. Her friends in Bloomsbury took to calling him the major, and wondered how to assimilate such a seemingly stereotypical and masculine member of the English upper middle classes into their circle. They were to find that he fitted in rather well."

Ralph Partridge went to live with Carrington and Strachey at Mill House. Carrington began an affair with Partridge. According to Strachey's biographer, Stanford Patrick Rosenbaum, they created: "A polygonal ménage that survived the various affairs of both without destroying the deep love that lasted the rest of their lives. Strachey's relation to Carrington was partly paternal; he gave her a literary education while she painted and managed the household. Ralph Partridge... became indispensable to both Strachey, who fell in love with him, and Carrington." However, Frances Marshall denied that the two men were lovers and that Lytton quickly realised that Ralph was "completely heterosexual".

Gerald Brenan, had served with Ralph Partridge during the First World War, was a regular visitor to Mill House when he was in England. Brenan later described an early meeting with Carrington and Strachey: "Carrington came to the door and with one of her sweet, honeyed smiles welcomed me in. She was wearing a long cotton dress with a gathered skirt and her straight yellow hair, now beginning to turn brown, hung in a mop round her head. But the most striking thing about her was her eyes, which were of an intense shade of blue and very long-sighted, so that they took in everything they looked at in an instant. Passing a door through which I saw bicycles, we came into a sitting room, very simply furnished, in which a tall, thin, bearded man was stretched out in a wicker armchair with his long legs twisted together. Carrington introduced me to Lytton who, mumbling something I did not catch, held out a limp hand, and then led me through a glass door into an apple orchard where I saw Ralph, dressed in nothing but a pair of dirty white shorts, carrying a bucket."

In 1918 Lytton Strachey published Eminent Victorians (1918). The book was an irreverent look at the lives of Florence Nightingale, Thomas Arnold, Charles George Gordon and Henry Edward Manning. The historian, Gretchen Gerzina, has pointed out: "Not only did the book completely revise the art of biography from something long and dull to a quick-paced and creative form, but Lytton suddenly found himself a well-known and socially desirable character. Further he began to enjoy, for the first time in his life, a comfortable and independent income."

Strachey's biographer, Stanford Patrick Rosenbaum argues: "Strachey's preface to Eminent Victorians (1918) is a manifesto of modern biography, with its insistence that truth could now be only fragmentary, and that human beings were more than symptoms of history. The biographer's responsibility was to preserve both a becoming brevity and his own freedom of spirit, which for Strachey meant illustrating and exposing lives rather than imposing explanations on them.... Strachey's portraits are unified by a point of view that ironically juxtaposes the psychology and careers of his subjects."

Frances Marshall was a close friend of Dora Carrington during this period: "Her love for Lytton was the focus of her adult life, but she was by no means indifferent to the charms of young men, or of young women either for that matter; she was full of life and loved fun, but nothing must interfere with her all-important relation to Lytton. So, though she responded to Ralph's adoration, she at first did her best to divert him from his desire to marry her. When in the end she agreed, it was partly because he was so unhappy, and partly because she saw that the great friendship between Ralph and Lytton might actually consolidate her own position."

Virginia Woolf assumed that Carrington was having a sexual relationship with Lytton Strachey. However, she recalled in her diary on 2nd July, 1918: "After tea Lytton and Carrington left the room ostensibly to copulate; but suspicion was aroused by a measured sound proceeding from the room, and on listening at the keyhole it was discovered that they were reading aloud Macaulay's Essays!"

Dora Carrington married Ralph Partridge in 1921. She wrote to Lytton Strachey on her honeymoon: "So now I shall never tell you I do care again. It goes after today somewhere deep down inside me, and I'll not resurrect it to hurt either you or Ralph. Never again. He knows I'm not in love with him... I cried last night to think of a savage cynical fate which had made it impossible for my love ever to be used by you. You never knew, or never will know the very big and devastating love I had for you ... I shall be with you in two weeks, how lovely that will be. And this summer we shall all be very happy together."

In 1924 Strachey purchased Ham Spray House in Ham, Wiltshire, for £2,100. Dora and Ralph were invited to live with Strachey. According to Michael Holroyd, the author of Lytton Strachey (1994): "Ham Spray House had no drains or electric light and was in need of general repairs... The builders started work there in early spring... Even with some help from a legacy which Ralph had received on his father's death, it was all turning out to be fearfully expensive." Later, the loft at the east end of the house was converted into a studio for Carrington.

Julia Strachey, who visited her at Ham Spray House, recalls: "From a distance she (Carrington) looked a young creature, innocent and a little awkward, dressed in very odd frocks such as one would see in some quaint picture-book; but if one came closer and talked to her, one soon saw age scored around her eyes - and something, surely, a bit worse than that - a sort of illness, bodily or mental. She had darkly bruised, hallowed, almost battered sockets."

Brenan was a regular visitor to Ham Spray House when he was in England. Brenan later described an early meeting with Dora Carrington: "Carrington came to the door and with one of her sweet, honeyed smiles welcomed me in. She was wearing a long cotton dress with a gathered skirt and her straight yellow hair, now beginning to turn brown, hung in a mop round her head. But the most striking thing about her was her eyes, which were of an intense shade of blue and very long-sighted, so that they took in everything they looked at in an instant." Passing a door through which I saw bicycles, we came into a sitting room, very simply furnished, in which a tall, thin, bearded man was stretched out in a wicker armchair with his long legs twisted together. Carrington introduced me to Lytton who, mumbling something I did not catch, held out a limp hand, and then led me through a glass door into an apple orchard where I saw Ralph, dressed in nothing but a pair of dirty white shorts, carrying a bucket. He came forward to meet me with his big blue eyes rolling with fun and gaiety and carried me off to see the ducks and grey-streaked Chinese geese that he had recently bought... After this I was introduced to the tortoiseshell cat, which to his delight was rolling on its back in the grass in the frenzies of heat, and taken on to the kitchen where a buxom, fair-haired village girl of twenty, whom he addressed in a very flirtatious manner, was busy among the pots and pans.

Lytton Strachey had a sexual relationship with Philip Ritchie but he died of pneumonia in 1927. This was followed with a relationship with the publisher Roger Senhouse. Meanwhile Dora Carrington continued her affair with Gerald Brenan. Carrington enjoyed a close relationship with Alix Strachey, who she had attempted to seduce. She wrote in December 1928: "I send you my love. I wish it was for some use." She also had similar feelings for Julia Strachey. She told Brenan that she was strongly attracted to Julia and that she was "sleeping night after night in my house, and there's nothing to be done, but to admire her from a distance, and steal distracted kisses under cover of saying goodnight."

Dora Carrington wrote in her diary in 1929 that her sexual relationships were having a detrimental impact on her art. "I would like this year (since for the first time I seem to be without any relations to complicate me) to do more painting. But this is a resolution I have made for the last 10 years." However, later that year she began a relationship with Beakus Penrose, the younger brother of Roland Penrose. Her biographer, Gretchen Gerzina, has argued: "She may have found a sexual awakening with Henrietta - and there is no evidence that she ever had another woman as a lover - but ultimately it was a romance with a man she craved."

In 1931 Strachey became extremely ill. He had a fever that would not go away and constantly felt tired. At first he was diagnosed as having typhoid. He then saw another specialist who suggested it was ulcerative colitis. Frances Marshall pointed out: "In those days bulletins were published in the daily papers mentioning the progress of well-known people's illnesses. Lytton rated this degree of importance and the press often rang up, though the nice lady at the local exchange dealt with their queries and kept them supplied with news... On Christmas Day 1931 he was given up for dead. In the evening he made an astonishing recovery from near-unconsciousness."

Strachey told his nurse: "Darling Carrington. I love her. I always wanted to marry Carrington and I never did." Dora Carrington later recalled: "He could never have said anything more consoling. Not that I would have, even if he had asked me. But it was happiness to know he secretly had loved me so much." On 19th January 1932, Carrington asked his nurse if there was any chance that he might survive the illness. She replied: "Oh no - I don't think so now". Soon afterwards she went into the garage and tried to kill herself. However, during the night Ralph Partridge went looking for her and "found her in the garage with the car engine running, rushed in and dragged her out".

Lytton Strachey died of undiagnosed stomach cancer on 21st January 1932. Carrington went into deep depression. Gerald Brenan wrote to Carrington claiming: "To be happy you won't have to forget him, only to think of him without pain and that I really believe may be easier than you can now imagine."

Carrington kept a journal where she tried to communicate with Strachey. On 12th February 1932 Carrington wrote: "They say one should keep your standards & your values of life alive. But how can I when I only kept them for you. Everything was for you. I loved life just because you made it so perfect & now there is no one left to make jokes with or talk to... I see my paints, & think it is no use for Lytton will never see my pictures now, & I cry. And our happiness was getting so much more. This year there would have been no troubles, no disturbing loves... Everything was designed for this year. Last year we recovered from our emotions, & this autumn we were closer than we had ever been before. Oh darling Lytton you are dead & I can tell you nothing."

Frances Marshall was with Ralph Partridge when he received a phone-call on 11th March 1932. "The telephone rang, waking us. It was Tom Francis, the gardener who came daily from Ham; he was suffering terribly from shock, but had the presence of mind to tell us exactly what had happened: Carrington had shot herself but was still alive. Ralph rang up the Hungerford doctor asking him to go out to Ham Spray immediately; then, stopping only to collect a trained nurse, and taking Bunny with us for support, we drove at breakneck speed down the Great West Road.... We found her propped on rugs on her bedroom floor; the doctor had not dared to move her, but she had touched him greatly by asking him to fortify himself with a glass of sherry. Very characteristically, she first told Ralph she longed to die, and then (seeing his agony of mind) that she would do her best to get well. She died that same afternoon."

On this day in 1881 Tsar Alexander II was assassinated. Alexander, the eldest son of Tsar Nicholas I, was born in Moscow on 17th April, 1818. Educated by private tutors, he also had to endure rigorous military training that permanently damaged his health.

In 1841 he married Marie Alexandrovna, the daughter of the Grand Duke of Hesse-Darmstadt. Alexander became Tsar of Russia on the death of his father in 1855. At the time Russia was involved in the Crimean War and in 1856 signed the Treaty of Paris that brought the conflict to an end.

The Crimean War made Alexander realize that Russia was no longer a great military power. His advisers argued that Russia's serf-based economy could no longer compete with industrialized nations such as Britain and France.

Alexander now began to consider the possibility of bringing an end to serfdom in Russia. The nobility objected to this move but as Alexander told a group of Moscow nobles: "It is better to abolish serfdom from above than to wait for the time when it will begin to abolish itself from below".

In 1861 Alexander issued his Emancipation Manifesto that proposed 17 legislative acts that would free the serfs in Russia. Alexander announced that personal serfdom would be abolished and all peasants would be able to buy land from their landlords. The State would advance the the money to the landlords and would recover it from the peasants in 49 annual sums known as redemption payments.

Alexander II also introduced other reforms and in 1864 he allowed each district to set up a Zemstvo. These were local councils with powers to provide roads, schools and medical services. However, the right to elect members was restricted to the wealthy.

Other reforms introduced by Alexander included improved municipal government (1870) and universal military training (1874). He also encouraged the expansion of industry and the railway network.

Alexander's reforms did not satisfy liberals and radicals who wanted a parliamentary democracy and the freedom of expression that was enjoyed in the United States and most other European states. The reforms in agricultural also disappointed the peasants. In some regions it took peasants nearly 20 years to obtain their land. Many were forced to pay more than the land was worth and others were given inadequate amounts for their needs.

In 1876 a group of reformers established Land and Liberty. As it was illegal to criticize the Russian government, the group had to hold its meetings in secret. Influenced by the ideas of Mikhail Bakunin, the group published literature demanding that Russia's land should be handed over to the peasants.

Some reformers favoured a policy of terrorism to obtain reform and on 14th April, 1879, Alexander Soloviev, a former schoolteacher, tried to kill Alexander. His attempt failed and he was executed the following month. So also were sixteen other men suspected of terrorism.

The government responded to the assassination attempt by appointing six military governor-generals that imposed a rigorous system of censorship on Russia. All radical books were banned and known reformers were arrested and imprisoned.

In October, 1879, the Land and Liberty split into two factions. The majority of members, who favoured a policy of terrorism, established the People's Will. Soon afterwards the group decided to assassinate Alexander. The following month Andrei Zhelyabov and Sophia Perovskaya used nitroglycerine to destroy the Tsar train. However, the terrorist miscalculated and it destroyed another train instead. An attempt the blow up the Kamenny Bridge in St. Petersburg as the Tsar was passing over it was also unsuccessful.

The next attempt on Alexander's life involved a carpenter, Stefan Khalturin, who had managed to find work in the Winter Palace. Allowed to sleep on the premises, each day he brought packets of dynamite into his room and concealed it in his bedding.

On 17th February, 1880, Khalturin constructed a mine in the basement of the building under the dinning-room. The mine went off at half-past six at the time that the People's Will had calculated Alexander would be having his dinner. However, his main guest, Prince Alexander of Battenburg, had arrived late and dinner was delayed and the dinning-room was empty. Alexander was unharmed but sixty-seven people were killed or badly wounded by the explosion.

The People's Will contacted the Russian government and claimed they would call off the terror campaign if the Russian people were granted a constitution that provided free elections and an end to censorship. On 25th February, 1880, Alexander announced that he was considering granting the Russian people a constitution. To show his good will a number of political prisoners were released from prison. Loris Melikof, the Minister of the Interior, was given the task of devising a constitution that would satisfy the reformers but at the same time preserve the powers of the autocracy.

At the same time the Russian Police Department established a special section that dealt with internal security. This unit eventually became known as the Okhrana. Under the control of Loris Melikof, the Minister of the Interior, undercover agents began joining political organizations that were campaigning for social reform.

In January, 1881, Loris Melikof presented his plans to Alexander II. They included an expansion of the powers of the Zemstvo. Under his plan, each zemstov would also have the power to send delegates to a national assembly called the Gosudarstvenny Soviet that would have the power to initiate legislation. Alexander was concerned that the plan would give too much power to the national assembly and appointed a committee to look at the scheme in more detail.

The People's Will became increasingly angry at the failure of the Russian government to announce details of the new constitution. They therefore began to make plans for another assassination attempt. Those involved in the plot included Sophia Perovskaya, Andrei Zhelyabov, Gesia Gelfman, Nikolai Sablin, Ignatei Grinevitski, Nikolai Kibalchich, Nikolai Rysakov and Timofei Mikhailov.

In February, 1881, the Okhrana discovered that their was a plot led by Andrei Zhelyabov to kill Alexander. Zhelyabov was arrested but refused to provide any information on the conspiracy. He confidently told the police that nothing they could do would save the life of the Tsar.

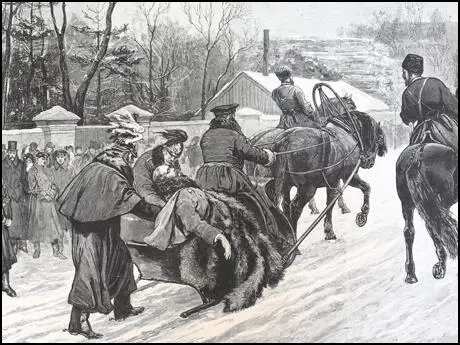

On 1st March, 1881, Alexander II was travelling in a closed carriage, from Michaelovsky Palace to the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg. An armed Cossack sat with the coach-driver and another six Cossacks followed on horseback. Behind them came a group of police officers in sledges.

All along the route he was watched by members of the People's Will. On a street corner near the Catherine Canal Sophia Perovskaya gave the signal to Nikolai Rysakov and Timofei Mikhailov to throw their bombs at the Tsar's carriage. The bombs missed the carriage and instead landed amongst the Cossacks. The Tsar was unhurt but insisted on getting out of the carriage to check the condition of the injured men. While he was standing with the wounded Cossacks another terrorist, Ignatei Grinevitski, threw his bomb. Alexander was killed instantly and the explosion was so great that Grinevitski also died from the bomb blast.

Of the other conspirators, Nikolai Sablin committed suicide before he could be arrested and Gesia Gelfman died in prison. Sophia Perovskaya, Andrei Zhelyabov, Nikolai Kibalchich, Nikolai Rysakov and Timofei Mikhailov were hanged on 3rd April, 1881.

On this day in 1899 Edmund Duffy was born in Jersey City. Duffy did not attend high school, but instead went to the Art Students League in New York City. It had no entrance requirements and no set course. With teachers such as Thomas Eakins, Robert Henri, John Sloan, Art Young, George Luks, Boardman Robinson, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Howard Pyle, George Grosz and George Bellows, it developed a reputation for progressive teaching methods and radical politics. In 1900 it had nearly a thousand students and was considered the most important art school in the country.

Students included James Montgomery Flagg, Mary Heaton Vorse, Howard Pyle, May Wilson Preston, Howard Christy, Alice Beach Winter, Ida Proper, Lou Rogers, Norman Rockwell, Mary Pinchot Meyer, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, Lee Bontecou, Helen Frankenthaler, Eva Hesse, Donald Judd, Knox Martin, James Rosenquist and Cy Twombly.

Duffy's first drawings appeared in the New York Tribune. He moved to London and worked for the London Evening News. Duffy worked in Paris for a few years, and he finally returned to the United States in 1922. He worked for two years with both the New York Leader and the Brooklyn Eagle.

He joined the Baltimore Sun as a cartoonist in 1924. The following year he went to Tennessee with H. L. Mencken to report on the Scopes Trial. The two men worked together for the next twenty-five years. Mencken valued Duffy's work very highly and once remarked: "Give me a good cartoonist and I can throw out half the editorial staff."

Duffy was one of the few white cartoonists willing to speak out against racial injustice. This included attacks on lynching and the Ku Klux Klan. Duffy supported the campaign led by Mary McLeod Bethune and Walter Francis White to persuade Congress to past an anti-lynching bill that had been proposed by Robert F. Wagner and Edward Costigan.

On 6th December, 1931, Edmund Duffy, published a cartoon in the Baltimore Sun about the lynching of 23 year-old Mattthew Williams by a white mob in Salisbury, Maryland, two days previously.

During Edmund Duffy's career, he won three Pulitzer Prizes. The cartoons were An Old Struggle Still Going On (27th February, 1930) that dealt with the struggle between communism and capitalism; California Points with Pride! (28th November, 1933) about California Governor James Rolph's reaction to the lynching of the killers of Brooke Hart and The Outstretched Hand (7th October, 1939) about Adolf Hitler and the invasion of Poland. Edmund Duffy died on 12th September 1962.

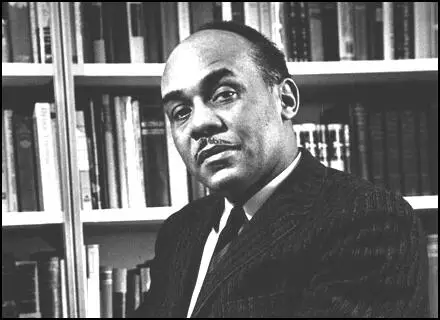

On this day in 1914 writer Ralph Ellison, the son of Lewis Alfred Ellison and Ida Millsap, was born in Oklahoma City.. It was later claimed that he was named after Ralph Waldo Emerson. Ralph's father, who ran a small business, died when he was only three years old.

In 1933 Ellison won a scholarship to study music at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, where he was taught by two very talented musicians, William Levi Dawson and Hazel Harrison. He also spent a lot of time in the library reading and eventually decided to become a writer.

Ellison joined the Federal Writers' Project in New York City in 1936. He met Richard Wright who encouraged him and published some of his short stories and reviews in New Challenge and the Negro Quarterly. Other work also appeared in the left-wing journal, New Masses, where he mixed with other radical writers and artists such as Max Eastman, Upton Sinclair, Sherwood Anderson, Erskine Caldwell, Alvah Bessie, James Agee, Langston Hughes, John Dos Passos, Josephine Herbst, Albert Maltz, Agnes Smedley, Theodore Dreiser, Floyd Dell, Art Young, William Gropper, Albert Hirschfeld, Carl Sandburg, Waldo Frank and Eugene O'Neill.

During the Second World War Ellison served in the Merchant Marine. With the support of his second wife, Fanny McConnell, who worked as a photographer, Ellison spent his time on his first novel, Invisible Man (1952). The book tells the story of a Southern black youth who goes to Harlem to join the fight against white oppression. The book was well received and won the National Book Award in 1953.

Irving Howe wrote: "No white man could have written it, since no white man could know with such intimacy the life of the Negroes from the inside; yet Ellison writes with an ease and humor which are now and again simply miraculous. Invisible Man is a record of a Negro's journey through contemporary America, from South to North, province to city, naive faith to disenchantment and perhaps beyond. There are clear allegorical intentions but with a book so rich in talk and drama it would be a shame to neglect the fascinating surface for the mere depths."

Saul Bellow added: "He (the main character in the novel) is recruited by white radicals and becomes a Negro leader, and in the radical movement he learns eventually that throughout his entire life his relations with other men have been schematic; neither with Negroes nor with whites has he ever been visible, real... one is accustomed to expect excellent novels about boys, but a modern novel about men is exceedingly rare. For this enormously complex and difficult American experience of ours very few people are willing to make themselves morally and intellectually responsible. Consequently, maturity is hard to find."

After the publication of his novel, Ellison travelled around Europe before settling in Rome. However, he was unable to write anything of substance and in 1958 he returned to the United States in order to teach American and Russian literature at Bard College in New York City. He also began work on his second novel, Juneteenth. Although he wrote over 2,000 pages, the novel was never completed. He told friends that he was not satisfied with what he had produced.

Ellison decided to concentrate on his academic career and taught at Rutgers University and Yale University. In 1964, Ellison published Shadow and Act, a collection of essays about life as a black man and his love of jazz. In 1970 he became a permanent member of the faculty at New York University as the Albert Schweitzer Professor of Humanities.

In 1986 he published Going to the Territory, a collection of essays that included studies of Richard Wright, William Faulkner and Duke Ellington. However, he never completed his novel and concentrated on his other interests, including work as a sculptor, musician and photographer.

Ralph Ellison died on 16th April, 1994, of pancreatic cancer. John F. Callahan, his literary executor, arranged the publication of Flying Home and Other Stories in 1996. Three years later he published a 368-page version of his second novel, Juneteenth. The complete version was published as Three Days Before the Shooting in 2010.

On this day in 1921 Margaret Haig Thomas, Lady Rhondda launched the Six Point Group of Great Britain, which focused on what she regarded as the six key issues for women: The six original specific aims were: (1) Satisfactory legislation on child assault; (2) Satisfactory legislation for the widowed mother; (3) Satisfactory legislation for the unmarried mother and her child; (4) Equal rights of guardianship for married parents; (5) Equal pay for teachers; (6) Equal opportunities for men and women in the civil service.

On this day in 1950 Klaus Fuchs is convicted of spying for the Soviet Union. Klaus Fuchs was born on 29th December, 1911, in Rüsselsheim, Germany. He was the third child in the family of two sons and two daughters of Emil Fuchs and his wife, Else Wagner. According to Mary Flowers: "His father, renowned for his high Christian principles, was a pastor in the Lutheran church who joined the Quakers later in life and eventually became professor of theology at Leipzig University. Fuchs's grandmother, mother, and one sister all took their own lives, while his other sister was diagnosed as schizophrenic."

Klaus Fuchs studied physics and mathematics at the University of Leipzig and in 1931 he joined the German Communist Party (KPD). He fled the country when Adolf Hitler took power in 1933. He taught in Paris before moving to England. He settled in Bristol and studied under Nevill Francis Mott, the Melville Wills Professor in Theoretical Physics at the University of Bristol. Soon after he arrived in the city he was the subject of a police enquiry. "The German Counsul in Bristol named him as an extremist left-wing agitator. Not a great deal of credence was given to the allegation because such denunciations were fairly frequent and anyway the young physicist was just one of thousands of Germans who fled their homeland for ideological reasons."

After obtaining his PhD. He took a DSc at Edinburgh University under the guidance of Max Born, one of the pioneers of the new quantum mechanics. After the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 he was interned with other German refugees in camps on the Isle of Man. According to Andrew Boyle, The Climate of Treason (1979): "His spell behind barbed wire had merely hardened Fuchs's secret Communist faith, a process not reversed by the German attack on the Soviet Union." He was then transferred to Sherbrooke Camp in Canada where he met Hans Kahle, who had fought with the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War. Kahle gave Fuchs some addresses of left wing friends, including that of Charlotte Haldane.

Klaus Fuchs was was released following representations from many distinguished scientists, protesting that his skills were going to waste. Rudolf Peierls, who worked at Birmingham University, recruited Klaus Fuchs to help him with his research into atomic weapons: "In 1940, when it was clear that an atomic weapon was a serious possibility, and that it was urgent to do experimental and theoretical work, I wanted someone to help me with the theoretical side. Most competent theoreticians were already doing something important, and when I heard that Fuchs, whom I knew and respected as a physicist from his work at Bristol, was back in the UK, temporarily in Edinburgh, it seemed a good idea to try to get him to come to Birmingham. There was at first some difficulty about security clearance, and I was told I could not tell him what it was all about... I explained that in the kind of work that had to be done he could be of no use to me and unless he knew exactly what one was trying to do, and that there was no half-way house. In the end he was cleared."

According to a document in the NKVD archives, Klaus Fuchs began spying for the Soviet Union in August 1941: "Klaus Fuchs has been our source since August 1941, when he was recruited through the recommendation of Urgen Kuchinsky (an exiled German Communist resident in Great Britain). In connection with the laboratory's transfer to America, Fuchs's departure is expected, too. I should inform you that measures to organize a liaison with Fuchs in America have been taken by us, and more detailed data will be conveyed in the course of passing Fuchs to you." Another file says that Fuchs passed material to their agent for the first time in September 1941.

Fuch's Soviet controller was Ursula Beurton: "Klaus and I never spent more than half an hour together when we met. Two minutes would have been enough but, apart from the pleasure of the meeting, it would arouse less suspicion if we took a little walk together rather than parting immediately. Nobody who did not live in such isolation can guess how precious these meetings with another German comrade were."

In 1943 Klaus Fuchs went with Peierls to join the Manhattan Project, which was the codename given to the American atomic bomb programme based in Los Alamos. However, Fuchs was based in the research unit in New York City. Over the next few months he met five times with his Soviet contact. On 21st January, 1944, the agent sent a report on Fuchs to GRU headquarters: "While working with us, Fuchs passed us a number of theoretical calculations on atomic fission and creation of the uranium bomb... His materials were appraised highly." The report also stated that Fuchs was a "devout Communist... whose only financial reward consisted of occasional gifts."

Fuchs's courier was Harry Gold. He sometimes went to the house of Fuchs' sister, who was living in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to meet with Fuchs. Allen Weinstein, the author of The Hunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America (1999), has pointed out: "The NKVD had chosen Gold, an experienced group handler, as Fuchs' contact on the grounds that it was safer than having him meet directly with a Russian operative, but Semyon Semyonov was ultimately responsible for the Fuchs relationship."

Gold reported after his first meeting with Klaus Fuchs: "He (Fuchs) obviously worked with our people before and he is fully aware of what he is doing... He is a mathematical physicist... most likely a very brilliant man to have such a position at his age (he looks about 30). We took a long walk after dinner... He is a member of a British mission to the U.S. working under the direct control of the U.S. Army... The work involves mainly separating the isotopes... and is being done thusly: The electronic method has been developed at Berkeley, California, and is being carried out at a place known only as Camp Y... Simultaneously, the diffusion method is being tried here in the East... Should the diffusion method prove successful, it will be used as a preliminary step in the separation, with the final work being done by the electronic method. They hope to have the electronic method ready early in 1945 and the diffusion method in July 1945, but (Fuchs) says the latter estimate is optimistic. (Fuchs) says there is much being withheld from the British. Even Niels Bohr, who is now in the country incognito as Nicholas Baker, has not been told everything."

Fuchs met Gold for a second meeting on 25th February, 1944, where he turned material with his personal work on "Enormoz". At a third meeting on 11th March, he delivered fifty additional pages. Gold reported to Semyon Semyonov that "(Klaus Fuchs) asked me how his first stuff had been received, and I said quite satisfactorily but with one drawback: references to the first material, bearing on a general description of the process, were missing, and we especially needed a detailed schema of the entire plant. Clearly, he did not like this much. His main objection, evidently, was that he had already carried out this job on the other side (in England), and those who receive these materials must know how to connect them to the scheme. Besides, he thinks it would be dangerous for him if such explanations were found, since his work here is not linked to this sort of material. Nevertheless, he agreed to give us what we need as soon as possible." On 28th March, 1944, Fuchs complained to Gold that "his work here is deliberately being curbed by the Americans who continue to neglect cooperation and do not provide information." He even suggested that he might learn more by returning to England. If Fuchs went back, "he would be able to give us more complete general information but without details."

Frustrated at the lack of success in the United States in October 1944 Major Pavel Fitin sent Leonid Kvasnikov to build up a network of atomic spies. The following month Kvasnikov was pleased to hear that Fuchs had been transferred to Los Alamos. This included Fuchs, Theodore Hall, Harry Gold, Julius Rosenberg, David Greenglass and Ruth Greenglass. On 8th January, 1945, Kvasnikov sent a message to Fitin about the progress he was making. "(David Greenglass) has arrived in New York City on leave... In addition to the information passed to us through (Ruth Greenglass), he has given us a hand-written plan of the layout of Camp-2 and facts known to him about the work and the personnel. The basic task of the camp is to make the mechanism which is to serve as the detonator. Experimental work is being carried out on the construction of a tube of this kind and experiments are being tried with explosive."

Major Pavel Fitin, the head of NKVD's foreign intelligence unit, claimed that Klaus Fuchs was the most important figure in the project he had given the codename "Enormoz". In November 1944 he reported: "Despite participation by a large number of scientific organization and workers on the problem of Enormoz in the U.S., mainly known to us by agent data, their cultivation develops poorly. Therefore, the major part of data on the U.S. comes from the station in England. On the basis of information from London station, Moscow Center more than once sent to the New York station a work orientation and sent a ready agent, too (Klaus Fuchs)." Another memorandum from NKVD stated that "Fuchs is an important figure with significant prospects and experience in agent's work acquired over two years spent working with the neighbors (GRU). After determining at early meetings his status in the country and possibilities, you may move immediately to the practical work of acquiring information and materials."

The Soviet government was devastated when the atom bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6th and 9th August, 1945. Allen Weinstein, the author of The Hunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America (1999): "On August 25, Kvasnikov responded that the station had not yet received agent reports on the explosions in Japan. As for Fuchs and Greenglass, their next meetings with Gold were scheduled for mid-September. Moscow found Kvasnikov's excuses unacceptable and reminded him on August 28 of the even greater future importance of information on atomic research, now that the Americans had produced the most destructive weapon known to humankind."

Pavel Fitin wrote to Vsevolod Merkulov: "Practical use of the atomic bomb by the Americans means the completion of the first stage of enormous scientific-research work on the problem of releasing intra-atomic energy. The fact opens a new epoch in science and technology and will undoubtedly result in rapid development of the entire problem of Enormoz - using intra-atomic energy not only for military purposes but in the entire modern economy. All this gives the problem of Enormoz a leading place in our intelligence work and demands immediate measures to strengthen our technical intelligence."

In 1946 Klaus Fuchs returned to England, where he was appointed by John Cockcroft as head of the theoretical physics division at the newly created British Nuclear Research Centre at Harwell. Fuchs approached members of the Communist Party of Great Britain in order to get back in contact with the NKVD. On 19th July, 1947, Fuchs met Hanna Klopshtock in Richmond Park.

Klopshtock arranged for Fuchs to meet Alexander Feklissov, London's deputy station chief for scientific and technical intelligence. Fuchs explained to Feklissov the principle of the hydrogen bomb on which Enrico Fermi and Edward Teller were working on at the University of Chicago. Feklissov reported: "I thanked him once again for helping us and, having noted that we know about his refusal to accept material help from us in the past, said that now conditions had changed: his father was his dependent, his ill brother (who has tuberculosis) needed his help... therefore we considered it imperative to propose our help as an expression of gratitude." Fuchs was given £200. However, he returned £100 on the grounds that he could not explain the sudden appearance of £200.

In March 1948, Feklissov received orders to keep clear of Klaus Fuchs. This was because the Daily Express had reported that British counter-intelligence were investigating three unnamed scientists who were suspected of being members of the Communist Party of Great Britain. Feklissov was also told that one of Fuchs' former contacts (Ursula Beurton) had been interviewed by the FBI. The point was made that Fuchs would probably not now be in a position to give them any worthwhile information as even if he was not arrested, he would probably be barred from participating in secret scientific research work on the atomic problem. However, Feklissov continued to have meetings with Fuchs.

The NKVD became especially concerned when Judith Coplon was arrested on 4th March, 1949 in New York City as she met with Valentin Gubitchev, a Soviet employee on the United Nations staff. They discovered that she had in her handbag twenty-eight FBI memoranda. Eight days later Moscow sent Feklissov a message: "In connection with the latest events in (New York City) and in order to avoid repetition of such cases in other places, it is necessary to revise urgently and most carefully the practice of holding meetings... We ask you to revise... all methods for carrying out meetings, especially with (Fuchs)."

On 12th September 1949, MI5 was sent documents that had been uncovered by the Venona Project that suggested that Fuchs was a Soviet spy. His telephones were tapped and his correspondence intercepted at both his home and office. Concealed microphones were installed in Fuchs's home in Harwell. Fuchs was tailed by B4 surveillance teams, who reported that he was difficult to follow. Although they discovered he was having an affair with the wife of his line manager, the investigation failed to produce any evidence of espionage.

In January 1950, Percy Sillitoe, the head of MI5, wrote to Fuchs's boss, Sir Archibald Rowlands pointing out: "We have had Fuchs' activities under intensive investigation for more than four months. Since it has been generally agreed that Fuchs' continued employment is a constant threat to security and since our elaborate investigation has produced no dividends, I should be grateful if you would be kind enough to arrange for Fuchs' departure from Harwell as soon as is decently possible."

Fuchs was interviewed by MI5 officers but he denied any involvement in espionage and the intelligence services did not have enough evidence to have him arrested and charged with spying. Jim Skardon later recalled: "He (Klaus Fuchs) was obviously under considerable mental stress. I suggested that he should unburden his mind and clear his conscience by telling me the full story." Fuchs replied "I will never be persuaded by you to talk." The two men then went to lunch: "During the meal he seemed to be resolving the matter and to be considerably abstracted... He suggested that we should hurry back to his house. On arrival he said that he had decided it would be in his best interests to answer my questions. I then put certain questions to him and in reply he told me that he was engaged in espionage from mid 1942 until about a year ago. He said there was a continuous passing of information relating to atomic energy at irregular but frequent meetings."

Klaus Fuchs explained to Skardon: "Since that time I have had continuous contact with the persons who were completely unknown to me, except that I knew they would hand whatever information I gave them to the Russian authorities. At that time I had complete confidence in Russian policy and I believed that the Western Allies deliberately allowed Russia and Germany to fight each other to the death. I had therefore, no hesitation in giving all the information I had, even though occasionally I tried to concentrate mainly on giving information about the results of my own work. There is nobody I know by name who is concerned with collecting information for the Russian authorities. There are people whom I know by sight whom I trusted with my life." A few days later J. Edgar Hoover informed President Harry S. Truman that "we have just gotten word from England that we have gotten a full confession from one of the top scientists, who worked over here, that he gave the complete know-how of the atom bomb to the Russians." As Christopher Andrew, the author of The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009) pointed out: "What Fuchs had failed to realize was that, but for his confession, there would have been no case against him, Skardon's knowledge of his espionage, which had so impressed him, derived from... Verona... and unusable in court."

Klaus Fuchs was found guilty on 1st March 1950 of four counts of breaking the Official Secrets Act by "communicating information to a potential enemy". After a trial lasting less than 90 minutes, Lord Rayner Goddard sentenced him to fourteen years' imprisonment, the maximum for espionage, because the Soviet Union was classed as an ally at the time. Hoover reported that "Fuchs said he would estimate that the information furnished by him speeded up by several years the production of an atom bomb by Russia."

Fuchs was released on 23rd June 1959 after serving nine years and four months. Immediately after leaving Wakefield Prison he joined his father and one of his nephews in what had become the German Democratic Republic (GDR), where he was appointed deputy director of the Institute for Nuclear Research near Dresden. Fuchs married a friend from his student days, a fellow communist called Margarete Keilson. They had no children.

Klaus Fuchs died on 28th January, 1988.

On this day in 1980 Dixie Dean died. William (Dixie) Dean was born in Birkenhead on 22nd January 1907. He played football for Laird Street School, Moreton Bible Class, Heswell and Pensby United before joining Tranmere Rovers in November 1923.

Although the club was struggling at the bottom of the Third Division of the Football League, Dean managed to score 27 goals in 30 games. In March 1925 Dean joined Everton in the First Division for a transfer fee of £3,000. He made his first appearance against Arsenal at Highbury and scored on his home debut a week later against Aston Villa.

Dixie Dean was Everton's top scorer in his first full season with the club (1925-26). In Who's Who of Everton (2004) Tony Matthews described him as: "A football immortal, strong, dashing with a powerful right-foot shot and exceptional heading ability, Dixie Dean was, without doubt, one of the greatest centre-forwards of his era."

He suffered a serious motorcycle accident in Holywell in 1926, in which he suffered a fractured skull and jaw. He was told by doctors that he could not play football again. They were particularly concerned about the dangers posed by heading the ball.

Dean ignored that advice and was once again Everton's top scorer in the 1926-27 season. This included a large number of headed goals. In February 1927 Dean won his first international cap playing for England against Wales. Dean scored after 10 minutes and added a second before the end of the game. The following month he scored two more against Scotland. In May 1927, Dean scored hat-tricks against both Belgium and Luxembourg. In his first five games for England he scored an amazing twelve goals.

Dean was in sensational form in the 1927-28 season. He scored seven hat-tricks that season and ended up with a record-breaking 60 league goals in 39 games. Everton won the First Division title that season with 53 points, two more than their rivals Huddersfield Town.

Dean was also Everton's top scorer in the 1928-29 season. He repeated this feat in 1929-30 but could not save Everton from being relegated. Everton easily won the Second Division championship in the 1930-31 season. Dean scored in 12 consecutive league games and once again was the club's leading scorer.

Everton won the First Division championship in 1931-32. Dean scored eight hat-tricks that season and for the seventh successive season was Everton's top scorer. Dean was also recalled to the international side and scored against Spain in December 1931. All told, he scored 18 goals in 16 games for England.

Dean also scored 28 FA Cup goals for Everton including one in the club's 3-0 victory over Manchester City in the 1933 FA Cup Final.

Dean's body took a terrible hammering during his career and he suffered several spells out of the side with injuries. He failed to be leading scorer for Everton in the 1933-34 season but regained his position as the best marksman at the club in 1934-35.

Matt Busby played against Dean several times. In his autobiography he pointed out: "To play against Dixie Dean was at once a delight and a nightmare. He was a perfect specimen of an athlete, beautifully proportioned, with immense strength, adept on the ground but with extraordinary skill in the air. However close you watched him, his timing in the air was such that he was coming down before you got anywhere near him, and he hit that ball with his head as hard and as accurate as most players could kick it. Defences were close to panic when corners came over. And though he scored a huge tally of goals with headers he was an incredibly unselfish and amazingly accurate layer-off of chances for others. He was resilient in face of the big, tough centre-halves of his clay - and I cannot think of one centre-half today to match up with that lot, though it was often the unstoppable force against the immovable object - and he was a thorough sportsman."

Eddie Hapgood, the Arsenal full-back agreed: "Dixie Dean, a wizard with his feet, but just as deadly with his head, as strong as a house, and just as hard to knock off the ball, as clean in his play as a new pin, a great sportsman, and a trier to the end. Dixie was always a tough handful, not only because he was so big and fast, but because he used to roam out on to the wings, taking the centre-half with him, and, frequently, slipping him, making it extremely hard for the rest of the defence to keep some sort of order."

In December, 1936, Everton signed Tommy Lawton for a fee of £6,500. It was a record fee for a teenager. ne of the attractions of the deal was that Lawton now had the opportunity to play with Dean. When they met for the first-time, Dean put his arm round Lawton and said: "I know you've come here to take my place. Anything I can do to help you I will. I promise, anything at all." Dean was thirty years old and after suffering several serious injuries, he knew that there was not much time left for him at the top. Dean kept his promise and spent a lot of time with Lawton on the training field. Gordon Watson, who played at inside-left for Everton, later recalled: "Lawton and Dean used to work together under the main stand, Dean throwing up a large cased ball, stuffed with wet paper to make it as heavy as a medicine ball".

Six weeks after joining the club, Tommy Lawton was brought into the first team for an away match against Wolverhampton Wanderers, as Dean was rested prior to a fifth round FA Cup tie with Tottenham Hotspur. Lawton found it difficult playing against the England centre-half, Stan Cullis, however, he did score a goal 15 minutes from the end.

Everton drew the FA Cup tie with Tottenham Hotspur 1-1 and it was decided to play Tommy Lawton alongside Dixie Dean in the replay. In the second minute Lawton scored with a tremendous shot from outside the penalty area. Dean turned to Joe Mercer and said: "Well, that's it then. That's the swan song. That's the end of it." Dean realised that it would not be long before this talented player took his place in the side.

After twenty minutes Albert Geldard provided the centre for Dean to put 2-0 up. Dean later added a third but Tottenham Hotspur scored four to go through to the next round.

In the next game Everton beat Leeds United 7-0 with Dean and Lawton both scoring good goals. At the end of the 1936-37 season Dean had scored 24 goals in his 36 league games whereas Lawton had three in ten.

John Jones, Everton's young full-back, later argued that it was Dixie Dean who was the main coach at the club: "Dixie was the boss. Young players at Everton had to keep in order otherwise they were pretty soon stepped on... It was Dixie, along with a couple of England centre-halves, Charlie Gee and Tommy White who ran the show. Occasionally they'd call a meeting and they'd be telling the youngsters what to do. It was the best method of coaching I ever experienced." Lawton agreed but claimed that: "All they ever said was make sure you pass it to a man in the same shirt."

At the beginning of the 1937-38 season Tommy Lawton played at inside-right and Dixie Dean at centre-forward. The pairing did not work and Everton failed to win a game when they two men played together. On 8th September 1937, Dean was dropped and Lawton replaced him as centre-forward to play against Manchester City.

During his career he was known as Dixie Dean. This was a reference to his dark complexion and curly black hair. Dean hated being called "Dixie" and insisted that his friends and acquaintances used his real name. His biographer, Nick Walsh, argues in Dixie Dean: The Official Biography of a Goalscoring Legend (1977) that Dean felt that the term "had connections with colour problems connected with the Southern states of America, and therefore contained an inference that he was of that origin, or half-caste."

Dixie Dean was leaving the pitch after a game in 1938 when a spectator called out: "We will get you yet, you black bastard." Dean went over to him and punched him in the face. A policeman came running over but instead of arresting him, shook him by the hand.

At the end of the 1937-38 season Dean was transferred to Notts County in the Third Division. While at Everton he had scored 349 goals in 399 games. This included 19 against local rivals Liverpool. He only played nine games for his new club before moving to Ireland to play for Sligo Rovers.

After retiring from football in April 1941, Dixie Dean ran a pub in Chester. He had his right-leg amputated in 1976 and eventually died of a heart-attack on 1st March 1980 while watching Everton play Liverpool at Goodison Park.