On this day on 27th December

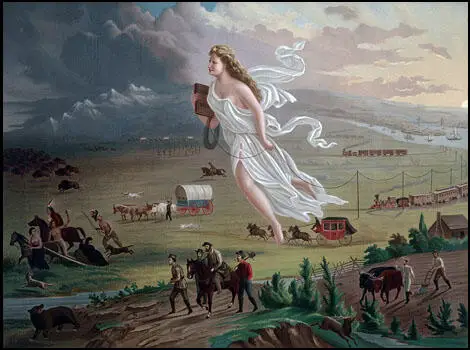

On this day in 1845 John L. O'Sullivan uses the term "manifest destiny" in the New York Morning News. It was used to encourage the spirit of expansionism. Over the following years the Manifest Destiny doctrine claimed that it should be the objective of the United States to absorb all of North America. This expansionism eventually ended in the acquisition of Texas, Oregon and California.

On this day in 1870 Ada Nield, the second child in a family of thirteen of William Nield, brickmaker, and his wife, Jane Hammond Nield was born in Audley, Staffordshire, on 28th January 1870. Ada was taken from school at the age of eleven to help look after the family, especially her younger sister May, who was an epileptic.

As the authors of One Hand Tied Behind Us (1978) have pointed out: "She had to leave school at eleven and take on the heavy responsibility of looking after her seven younger brothers, combining this with various odd jobs. Her father, a poor farmer, had to give up his farm for lack of capital, and moved his family to Crewe where he could more easily find another job."

In 1887 the Nield family moved to Crewe, and Ada worked at a shop in Nantwich. Later she found employment in the Compton Brothers clothing factory. In 1894 she published anonymously in The Crewe Chronicle, a series of letters describing conditions in her factory. As her biographer, David Doughan, pointed out: "These letters were circumstantially critical of the pay and conditions of factory women, especially compared to those of their male colleagues doing the same work. This resulted in Ada losing her position"

Ada Nield now joined the Independent Labour Party and soon afterwards the local branch stated: "It has been agreed at ILP meetings that the rights of women workers must be recognized, that common cause must be made with these our sisters, and that something definite must be done sooner or later - and the sooner the better." Ada, now a committed socialist, was also elected to the Nantwich Board of Guardians. According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999): "In 1896 she spent several weeks travelling around the north-east in the Clarion van, holding meetings to publicize the policies of the ILP." Ada was also a regular contributor to The Clarion and The Labour Leader. One biographer has commented that Ada "was very diffident about her personal appearance, but contemporaries record that she was very good-looking, with striking red hair."

In 1897 Ada Nield married George Chew, an ILP organizer. The following year, her only child, a daughter, was born. The couple settled in Rochdale where they ran a small shop. In 1900 she was given a full-time post by the Women's Trade Union League and she would take Doris, her young daughter, with her on her travels. During this period she became friends with Ramsay MacDonald, Margaret MacDonald, John Bruce Glasier, Katherine Glasier, Selina Cooper, John Robert Clynes and Mary Macarthur.

Ada Nield Chew was a member of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) and was totally against the policy of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). The main objective of the WSPU was to gain, not universal suffrage, the vote for all women and men over a certain age, but votes for women, “on the same basis as men.” This meant winning the vote not for all women but for only the small stratum of women who could meet the property qualification. As one critic pointed out, it was "not votes for women", but “votes for ladies.”

On the 16th December 1904 The Clarion published a letter from Ada Nield Chew on WSPU policy: "The entire class of wealthy women would be enfranchised, that the great body of working women, married or single, would be voteless still, and that to give wealthy women a vote would mean that they, voting naturally in their own interests, would help to swamp the vote of the enlightened working man, who is trying to get Labour men into Parliament."

The following month Christabel Pankhurst replied to the points that Ada made: "Some of us are not at all so confident as is Mrs Chew of the average middle class man's anxiety to confer votes upon his female relatives." A week later Ada Nield Chew retorted that she still rejected the policies in favour of "the abolition of all existing anomalies... which would enable a man or woman to vote simply because they are man or woman, not because they are more fortunate financially than their fellow men and women". As the authors of One Hand Tied Behind Us (1978) pointed out: "The fiery exchange ran on through the spring and into March. The two women both relished confrontation, and neither was prepared to concede an inch. They had no sympathy for the other's views, and shared no common experiences that might help to bridge the chasm."

In 1911 Ada Nield Chew and Selina Cooper became organizers for the NUWSS. She was also an active member of the Fabian Women's Group and wrote for various journals including The Common Cause, The Freewoman and The Englishwoman's Review.

Ada Nield Chew influenced the NUWSS decision in April 1912 to support Labour Party candidates in parliamentary by-elections. Emily Davies, a member of the Conservative Party, and Margery Corbett-Ashby, an active supporter of the Liberal Party, resigned from the NUWSS over this decision. However, others like Catherine Osler, resigned from the Women's Liberal Federation in protest against the government's attitude to the suffrage question.

The National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies established an Election Fighting Fund (EFF) to support these Labour candidates. The EFF Committee, which administered the fund, included Margaret Ashton, Henry N. Brailsford, Kathleen Courtney, Muriel de la Warr, Millicent Fawcett, Catherine Marshall, Isabella Ford, Laurence Housman, Margory Lees and Ethel Annakin Snowden.

On 4th August 1914, Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the NUWSS, declared that it was suspending all political activity until the First World War was over. Despite pressure from members of the NUWSS, Fawcett refused to argue against the war. Her biographer, Ray Strachey, argued: "She stood like a rock in their path, opposing herself with all the great weight of her personal popularity and prestige to their use of the machinery and name of the union." At a Council meeting of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies held in February 1915, Fawcett attacked the peace efforts of people like Mary Sheepshanks. Fawcett argued that until the German armies had been driven out of France and Belgium: "I believe it is akin to treason to talk of peace."

Ada Nield Chew was completely against this policy: "The militant section of the movement... would without doubt place itself in the trenches quite cheerfully, if allowed. It is now ... demanding, with all its usual pomp and circumstance of banner and procession, its share in the war. This is an entirely logical attitude and strictly in line with its attitude before the war. It always glorified the power of the primitive knock on the nose in preference to the more humane appeal to reason.... What of the others? The non-militants - so-called - though bitterly repudiating militancy for women, are as ardent in their support of militancy for men as their more consistent and logical militant sisters."

Ada Nield Chew disagreed with this policy and like Catherine Marshall, Helena Swanwick, Maude Royden, and Selina Cooper she refused on principle to undertake war work. Later she joined Mary Sheepshanks, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Emily Hobhouse and Chrystal Macmillan in becoming a member of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom.

After the war Ada Nield Chew ceased to be active in politics. According to David Doughan: "She now concentrated on the family business, starting an independent mail-order wholesale drapery line which met with such success that by 1922 she had to rent a small warehouse. She retired from the mail-order business in 1930. Although a seasoned traveller to all parts of Britain, she had never been abroad until 1927, when she and her daughter holidayed in the south of France. This she followed with a visit to her brother in South Africa in 1932, a round-the-world tour in 1935, and motoring holidays in France and Switzerland."

Ada Nield Chew died on 27th December 1945 at 55 Ormerod Road, Burnley, Lancashire.

On this day in 1882 John Scale, was born in Wales. He was educated at Repton School and Sandhurst Military College. On 8th May 1901 he was commissioned as a second lieutenant with the Royal Warwickshire Regiment. He was posted to India and in 1903 he was promoted to lieutenant with the 87th Punjabis Regiment in the British Indian Army.

In December 1912 he was transferred to Russia and the following year he qualified as a 1st Class Interpreter. On the outbreak of the First World War Scale was sent to the Western Front. In August 1916 he was attached to the to the British Secret Intelligence Service in Petrograd, where he served under Lieutenant-Colonel Samuel Hoare. Michael Smith, the author of Six: A History of Britain's Secret Intelligence Service (2010) has argued: "Scale, a 6 foot 4 inch Indian Army officer, had been serving on the Western Front when his ability to speak Russian led to him being called back to England to escort a group of influential Russian parliamentarians, and ultimately to his recruitment by Cumming to advise Hoare on military matters and act as the link-man with Thornhill and Steveni."

Christopher Andrew, the author of Secret Service: The Making of the British Intelligence Community (1985) argues: "Captain Scale, then on active service in France, was transferred to Petrograd to advise Hoare on battle order intelligence." One of his fellow agents described him as "tall, handsome, well-red, intelligent with a debonair manner which endeared him to everyone." Other members of the unit included Oswald Rayner, Cudbert Thornhill and Stephen Alley.

The British Secret Intelligence Service became concerned about the influence that Grigory Rasputin was having on Russian foreign policy. In a document written by Scale in November 1916 warned that "German intrigue was becoming more intense daily" and "the sinister influence which seemed to be clogging the war machine, Rasputin the drunken debauche influencing Russia's policy". Rumours also began to circulate that Tsarina Alexandra Fedorovna and Rasputin were leaders of a pro-German court group and were seeking a separate peace with the Central Powers in order to help the survival of the autocracy in Russia.

Scale recorded: "German intrigue was becoming more intense daily. Enemy agents were busy whispering of peace and hinting how to get it by creating disorder, rioting, etc. Things looked very black. Romania was collapsing, and Russia herself seemed weakening. The failure in communications, the shortness of foods, the sinister influence which seemed to be clogging the war machine, Rasputin the drunken debaucher influencing Russia's policy, what was to the be the end of it all?"

On 24th November 1916 Scale was sent to Romania to assist in a British Secret Intelligence Service operation to destroy the Romanian oil fields and corn harvest ahead of the invading German troops. According to Richard Cullen, the author of Rasputin (2010): "Muriel (Scale's daughter) was compelling during her interview when she reiterated that her father had told her he was sent to Romania because he had to be out of Russia at the time."

Grigory Rasputin was assassinated on 29th December, 1916. Soon afterwards Prince Felix Yusupov, Vladimir Purishkevich, the leader of the monarchists in the Duma, the Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich Romanov, Dr. Stanislaus de Lazovert and Lieutenant Sergei Mikhailovich Sukhotin, an officer in the Preobrazhensky Regiment, confessed to being involved in the killing.

On 7th January 1917, Stephen Alley wrote to Scale in Romania: "Although matters have not proceeded entirely to plan, our objective has clearly been achieved. Reaction to the demise of Dark Forces (a codename for Rasputin) has been well received by all, although a few awkward questions have already been asked about wider involvement. Rayner is attending to loose ends and will no doubt brief you on your return."

Richard Cullen, the author of Rasputin (2010), has argued that the assassination of Grigory Rasputin had been organised by Scale, Oswald Rayner and Stephen Alley: "Rasputin's death was calculated, brutal, violent and slow and it was orchestrated by John Scale, Stephen Alley and Oswald Rayner through the close personal relationship that existed between Rayner and Yusupov." Cullen adds: "Given the clear and supportable assertions that he (Scale) was involved in the plot to kill Rasputin, was this the reason for his absence from Petrograd?"

Scale narrowly escaped capture by the Bolsheviks after the Russian Revolution. In 1918 he became head of the British Secret Intelligence Service station in Stockholm. Scale, along with Oswald Rayner, recruited Russian speakers to infiltrate Russia. John Scale, who retired in 1927 at the rank of lieutenant colonel, died aged sixty-seven on 22nd April 1949.

On this day in 1900 Emily Hobhouse arrived in South Africa to investigate British use of concentration camps. Hobhouse, like many members of the radical wing of the Liberal Party, was opposed to the Boer War. Over the first few weeks of the war Emily spoke at several public meetings where she denounced the activities of the British government.

In late 1900 Emily was sent details of how women and children were being treated by the British Army. She later wrote: "poor women who were being driven from pillar to post, needed protection and organized assistance. And from that moment I was determined to go to South Africa in order to render assistance to them".

In October 1900, Emily formed the Relief Fund for South African Women and Children. An organisation set up: "To feed, clothe, harbour and save women and children - Boer, English and other - who were left destitute and ragged as a result of the destruction of property, the eviction of families or other incidents resulting from the military operations". Except for members of the Society of Friends, very few people were willing to contribute to this fund.

Hobhouse arrived in South Africa on 27th December, 1900. After meeting Alfred Milner, she gained permission to visit the concentration camps that had been established by the British Army. However, Lord Kitchener objected to this decision and she was now told she could only go to Bloemfontein.

She left Cape Town on 22nd January, 1901, and arrived at Bloemfontein two days later. There were at the time eighteen hundred people in the camp. Emily discovered "that there was a scarcity of essential provision and that the accommodation was wholly inadequate." When she complained about the lack of soap she was told, "soap is an article of luxury". She nevertheless succeeded ultimately to have it listed as a necessity, together with straw and kettles in which to boil the drinking water.

Over the next few weeks Emily visited several camps to the south of Bloemfontein, including Norvalspont, Aliwal North, Springfontein, Kimberley and Orange River. She was also allowed to visit Mafeking. Everywhere she directed the attention of the authorities to the inadequate sanitary accommodation and inadequate rations.

By the time that Emily returned to Bloemfontein in March 1901, the population had grown considerably. She later wrote: " The population had redoubled and had swallowed up the results of improvements that had been effected. Disease was on the increase and the sight of the people made the impression of utter misery. Illness and death had left their marks on the faces of the inhabitants. Many that I had left hale and hearty, of good appearance and physically fit, had undergone such a change that I could hardly recognize them."

Hobhouse argued that Kitchener’s "Scorched Earth" policy included the systematic destruction of crops and slaughtering of livestock, the burning down of homesteads and farms, and the poisoning of wells and salting of fields - to prevent the Boers from resupplying from a home base. Civilians were then forcibly moved into the concentration camps. Although this tactic had been used by Spain (Ten Years' War) and the United States (Philippine-American War), it was the first time that a whole nation had been systematically targeted.

Emily decided that she had to return to England in an effort to persuade the Marquess of Salisbury and his government to bring an end to the British Army's scorched earth and concentration camp policy. David Lloyd George and Charles Trevelyan took up the case in the House of Commons and accused the government of "a policy of extermination" directed against the Boer population. William St John Fremantle Brodrick, the Secretary of State for War argued that the interned Boers were "contented and comfortable" and stated that everything possible was being done to ensure satisfactory conditions in the camps.

The vast majority of MPs showed little sympathy to the plight of the Boers. Hobhouse later wrote: "The picture of apathy and impatience displayed here, which refused to lend an ear to undeserved misery, contrasted sadly with the scenes of misery in South Africa, still fresh in my mind. No barbarity in South Africa was as severe as the bleak cruelty of an apathetic parliament."

In August, 1901, the British government established a commission headed by Millicent Fawcett to visit South Africa. While the Fawcett Commission was carrying out the investigation, the government published its own report. According to the New York Times: “The War Office has issued a four-hundred-page Blue Book of the official reports from medical and other officers on the conditions in the concentration camps in South Africa. The general drift of the report attributes the high mortality in these camps to the dirty habits of the Boers, their ignorance and prejudices, their recourse to quackery, and their suspicious avoidance of the British hospitals and doctors.”

The Fawcett Commission confirmed almost everything that Emily Hobhouse had reported. After the war a report concluded that 27,927 Boers had died of starvation, disease and exposure in the concentration camps. In all, about one in four of the Boer inmates, mostly children, died. However, the South African historian, Stephen Burridge Spies argues in Methods of Barbarism: Roberts and Kitchener and Civilians in the Boer Republics (1977) that this is an under-estimate of those who died in the camps.

Hobhouse decided to return to South Africa but was warned by the authorities they would refuse permission for her to visit the camps. When Hobhouse arrived in Cape Town on Sunday 27th October, 1901, she was not allowed to leave her ship. In poor health, she decided to recuperate in the mountains of Savoy. It was while she was there that Hobhouse heard that the Boer leaders had signed the Peace Treaty of Vereeniging.

Hobhouse was also an opponent of British involvement in the First World War. On 3rd September, 1916, she wrote to a friend: "Think of our beloved fatherland, think of beautiful Italy, of France and of Germany, all of them working at full capacity to produce weapons of war and destruction. It seems as if we have reached the end of our civilization. It is all too hideous for words".

In 1921 the people of South Africa raised £2,300 and sent it to Hobhouse in recognition for the work she had done on their behalf during the Boer War. The money was sent to her with the explicit mandate that she had to buy a small house for herself somewhere along the coast of Cornwall. On 18th May, 1921, she replied: "I find it impossible to give expression to the feelings that overpowered me when I heard of the surprise you had prepared for me. My first impulse was not to accept any gift, or otherwise to devote it to some or other public end. But after having read and reread your letter, I have decided to accept your gift in the same simple and loving spirit in which it was sent to me."

Hobhouse purchased a house at St. Ives. On Christmas Day, 1921, she wrote to the organisers of the fund: "To you I owe everything that surrounds me now and that gives me a feeling of comfort and rest and security - the warmth of my little room - and the feeling of being at home. When I look back upon the year that has passed, I marvel more and more at everything that you and your people have done to ensure my happiness and my welfare".

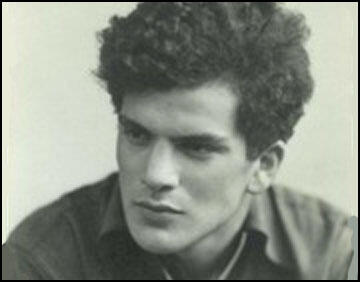

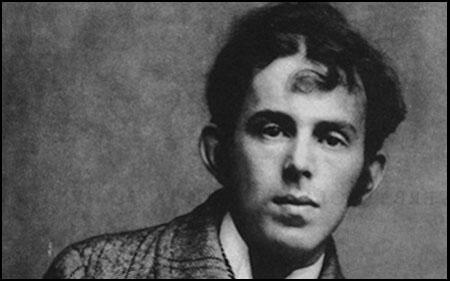

John Cornford, the son of Francis Macdonald Cornford (1874–1943) and Frances Crofts Cornford (1886–1960), was born in Cambridge on 27th December 1915. His father was professor of ancient philosophy at Cambridge University and his mother, the grand-daughter of Charles Darwin, was a published poet. He was named Rupert in memory of Rupert Brooke, who had been killed in the First World War just before he was born.

At the age of nine Cornford was sent as a boarder to Copthorne Preparatory School in Sussex. Francis Macdonald Cornford later recalled: "At Copthorne he became absorbed in cricket. His headmaster said that his style, as a player, was the most incredible he had ever seen. But his knowledge of the history of the game was exhaustive... Later, his knowledge of the more democratic Association Football became no less extensive."

In 1929 he obtained a scholarship to Stowe School. The following year he was joined by his brother, Christopher: "Already, by the time I joined him at Stowe in the autumn of 1930, he had begun to be critical of the school, as indeed of everything else. He was already anti-militarist and atheist - one of his favourite pastimes was to tie up the school chaplain in metaphysical knots during the Tuesday afternoon religious talks."

The following year he began writing poetry that had been inspired by the work of W.H. Auden, T.S. Eliot and Robert Graves. He also developed an interest in politics. Christopher Cornford recalled: "As young as fourteen and a half he became sympathetic to Socialism. As we strode together through the school grounds, among the great beech trees and lakes, the rotundas and monumental obelisks, in shiny blue serge Sunday suits and stiff collars unloosed, he explained to me the principles of the nationalisation of industry and the injustices of our economic system."

John Cornford also began reading books written by G. D. H. Cole, Harold Laski, Rajani Palme Dutt, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. He claimed that Cole's plan for socialism "isn't powerful enough emotional position to accumulate the colossal reserves of energy and fanaticism that are needed to bring through a revolution without violence". Cornford preferred Marx to Cole: "Cole's Socialism is without the strength of Communism because it is without the really important part of Marxism, his dialectical materialism and the interpretation of history." He described Palme Dutt as "extraordinarily intelligent, but almost equally bitter."

In 1932 he read Das Kapital and the Communist Manifesto. He also wrote a letter to his brother about the criticism that Karl Marx had received from Harold Laski. " It seems to me dishonest for men like Laski to dismiss the Marxist interpretation of history and yet proclaim Marx as a great prophet, because his wonderfully accurate prophecy is dependent on his interpretation of history. Where it seems to me that he went wrong is in applying terms like the class-struggle (which is a legitimate abbreviation of what actually happens) as the whole and simple truth. It's far more complicated than he seemed to realise. But I believe that in this, too, his limitations are important in making him intelligible."

When he was only sixteen he won an exhibition to Trinity College. Cornford spent that summer in London. He joined the Young Communist League and spent a lot of time at the London School of Economics. He also had a poem published in the Listener before taking up his place at university in October 1933. According to Michael De-la-Noy: "During his three years at Cambridge he wrote only nine poems, for he was spending fourteen hours a day on political activities."

A fellow student at university was Victor Kiernan. He later recalled: "He had his philosophy, or rather instinctive attitude, of which friends got only glimpses; not that lie was secretive, but that he followed Lenin in his contempt for all useless sentiment and psychological weakness. He recalled one's ideas of what Lenin was like in other ways. His politics, unlike those of many middle-class Socialists, were not based on humanitarianism alone. To him the movement was something that could call out and realise all his powers; it was the only atmosphere he could breathe."

John Cornford became very concerned about Adolf Hitler gaining power in Nazi Germany. In an article that he wrote in The Cambridge Left journal in 1934 he argued: "Fascism strives to cripple the working-class movement by murdering and torturing its leaders, suppressing its legal organisations and press, removing the right to strike in defence of wages and conditions, and all political rights whatsoever. Fascism exploits the Nationalist feelings of the petty bourgeoisie to divert their hostility towards the existing regime by whipping up a chauvinist frenzy against some foreign scapegoat - in Germany the Jews; in Poland the Ukrainian minority."

In March 1935 Cornford became a full member of the Communist Party of Great Britain. Despite the amount of time he spent on his political activities he achieved first classes in both parts of the history tripos (1935 and 1936). Cornford also became romantically attached to Rachel Peters and she gave birth to his illegitimate child. He later left Peters for Margot Heinemann.

Kenneth Sinclair Loutit recalled how John Cornford and James Klugman tried to recruit him into the Socialist Society: "My second meeting with James Klugman must have been after my return from Germany. He was accompanied by John Cornford. As contemporaries we all knew each other by sight, and Klugman remembered his previous recruiting visit. They said, very reasonably, that it was only by working together that people sharing the same goals could hope to achieve them, so I really could not do other than join the University Socialist Society. I had already told James the year before that I was not a joiner... John Cornford then took over asking what I saw as the most important thing for the next decade."

John Cornford wrote an article explaining why so many university students were joining the Communist Party of Great Britain. "The last few years have seen a considerable growth of Communist influence in the universities... It is no longer a phenomenon that can be dismissed as an outburst of transient youthful enthusiasm. It has established itself so firmly that any serious analysis of trends in the universities must take it into account... Communism in the universities is a serious force. It is serious because students do not easily or naturally become Communists. Communism has to fight down more prejudices, more traditions, more simple distortions of fact, than any other political organisation. It would not have gained ground without a serious appeal."

In 1936 Trinity College gave him a scholarship, and he planned to study the Elizabethans. However, on the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War he decided to go to Spain. Cornford reached Barcelona on 8th August 1936. He wrote to Margot Heinemann about the revolutionary spirit he found in Spain: "In Barcelona one can understand physically what the dictatorship of the proletariat means.... The mass of the people ... simply are enjoying their freedom. The streets are crowded all day, and there are big crowds round the radio palaces. But there is nothing at all like tension or hysteria... It is genuinely a dictatorship of the majority, supported by the over-whelming majority.

He met Franz Borkenau, an Austrian journalist, and the two men decided to travel to the front-line. He had already made up his mind to join the Worker's Party (POUM) army. He told his father in a letter: "After I had been three days in Barcelona it was clear, first, how serious the position was; second, that a journalist without a word of Spanish was just useless. I decided to join the militia."

Tom Wintringham later explained why Cornford had joined a group that was strongly influenced by the political ideas of Leon Trotsky and hostile to Joseph Stalin and his government in the Soviet Union: "In Barcelona he (John Cornford) found that the militia was being organized by the trade unions and political parties. He had no papers from England: he had not even brought his party membership card with him. So when he applied to the Hotel Colon, then the military headquarters of the party in which Barcelona's Socialists and Communists had joined forces, he was told to wait. Friendly but precise Germans, people taught by Bismarck as well as by exile to carry all necessary documents with them at all times, told him that he could not join the Thaelmann group, or any other unit of foreign volunteers organized by the United Socialist Party, until his standing as a known anti-Fascist was guaranteed by some document or by some person they knew. John was too restless, impatient for this. He flung off to join a rival party's militia, that of the P.O.U.M."

Cornford took part in an action at Perdiguera. He wrote to Harry Pollitt about his whereabouts and to inform him of the realities of the military situation in Spain. He also told Margot Heinemann about the battle he had taken part in and how it was reported in the POUM newspaper: "Today I found with interest but not surprise the distortions in the POUM press. The fiasco of the attack at Perdiguera is presented as a punitive expedition which was a success."

Cornford fought at Aragon in August 1936. The following month he fell ill and was sent to hospital. The authors of Journey to the Frontier have argued: "The precise nature of John's illness has never been established... it was disabling, and he suffered a few truly difficult days." Cornford was sent back to Cambridge to recuperate.

Cornford decided to use this as an opportunity to persuade some of his old friends to go to Spain. Bernard Knox later recalled: "In September I received a letter from my friend John Cornford, the leader of the Communist movement in Cambridge, who had just returned from Spain, where he had fought for a few weeks on the Aragon front, in a column organized by the Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista, the POUM, a party that was later to be suppressed as too revolutionary. He had returned to England to recruit a small British unit that would set an example of training and discipline (and shaving) to the anarchistic militias operating out of Barcelona. He asked me to join and I did so without a second thought."

Cornford recruited a group of twelve friends to join the International Brigades. Knox went with him to see his father, Francis Macdonald Cornford. "He had served as an officer in the Great War and still had the pistol he had had to buy when he equipped himself for France. He gave it to John, and I had to smuggle it through French Customs at Dieppe, for John's passport showed entry and exit stamps from Port-Bou and his bags were likely to be given a thorough going-over."

Cornford took the men to Albacete, where they received some military training. Bernard Knox later recalled: "Our British section was assigned (mainly, I suppose, because I could serve as interpreter) to the French Battalion, where we ended up in the compagnie mitrailleuse, the machine-gun company. But for the rest of September and all through October we had no machine guns, not even rifles; the only weapon around was John's pistol, which he kept well under wraps. Since we couldn't train with weapons, our days were spent practicing close-order drill (French, English, or sometimes Spanish) and going on route marches along the dusty roads of the province of Murcia. No one knew when or where we would be sent to fight when (if ever) the weapons arrived, though the scuttlebutt rumors had us held in reserve for a flanking movement via Ciudad Real that would take Franco, now moving steadily toward Madrid, in the rear."

Bernard Knox fought alongside Cornford in Spain. "Our baptism of fire was sharp and unexpected. We were scattered with our machine-guns along a crest which we had every reason to believe was as safe as anything could be in the Madrid area (which wasn't very safe), when we heard our first shell. Nobody minded much, because it burst a good forty yards behind us, but the next two or three showed us that they were feeling for the crest we were occupying... Our commander had gone up to advanced positions that night with one of our gun-crews, so John took over command that morning, inspecting the positions we had taken up, and criticising ruefully the way in which most of us came down the cliff. But it was not a bad performance for raw troops taken by surprise in a barrage."

John Cornford took part in the battle for Madrid and on 7th November 1936, and received a severe head wound. Sam Russell was with him when it happened: "When the smoke cleared there was John Cornford with blood pouring down his face and head. We later discovered that it was one of our own anti-aircraft shells that had fallen short and had come through the side of a wall. They took John off and that afternoon he came back with his head bandaged, looking very heroic and romantic."

While recovering he wrote some of his most important poems including Heart of the Heartless World. On 8th December, 1936, Cornford wrote to Margot Heinemann: " No wars are nice, and even a revolutionary war is ugly enough. But I'm becoming a good soldier, longish endurance and a capacity for living in the present and enjoying all that can be enjoyed. There's a tough time ahead but I've plenty of strength left for it. Well, one day the war will end - I'd give it till June or July, and then if I'm alive I'm coming back to you. I think about you often, but there's nothing I can do but say again, be happy, darling, And I'll see you again one day."

John Cornford insisted on going back to the front-line where he joined the recently formed British Battalion. He was killed near Lopera on 27th December 1936, his twenty-first birthday. According to Francis Beckett, the author of Enemy Within - the Rise and Fall of the British Communist Party (1995), Cornford was killed trying to retrieve the body of Ralph Fox. Cornford's best known work was published after his death: The Last Mile to Huesca and Poems from Spain.

On this day in 1916, MI5 begin the framing Alice Wheeldon. She was a socialist and a member of the Socialist Labour Party (SLP) . She was also active in the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). Her daughters, Hettie Wheeldon and Winnie Wheeldon, shared her feminist political views.

The outbreak of the First World War caused conflict between Alice and the WSPU. Alice was a pacifist and disagreed with the WSPU's strong support for the war. Sylvia Pankhurst and Charlotte Despard established the Women's Peace Army, an organisation that demanded a negotiated peace. Alice, Hettie Wheeldon and Winnie Wheeldon, all joined this new political group. Other members included Helena Swanwick and Olive Schreiner.

Alice and her daughters also joined the No-Conscription Fellowship (NCF). Other members included Clifford Allen, Fenner Brockway, Bertrand Russell, Philip Snowden, Bruce Glasier, Robert Smillie, C. H. Norman and Rev. John Clifford.

In 1915 Alice's daughter, Winnie, married Alfred Mason. The couple moved to Southampton, where Mason worked as a chemist and continued to be involved in the socialist and anti-war movement. Alice's son, William Wheeldon, was also active in the cause. On 31st August 1916, he appeared before Derby Borough Police Court charged with "wilfully obstructing police officers in the execution of their duty." The previous week he had attempted to stop the police move five conscientious objectors from the prison to the railway station. William was found guilty and sentenced to a month imprisonment.

Over 3,000,000 men volunteered to serve in the British Armed Forces during the first two years of the First World War. Due to heavy losses at the Western Front the government decided to introduce conscription (compulsory enrollment) by passing the Military Service Act. The NCF mounted a vigorous campaign against the punishment and imprisonment of conscientious objectors. About 16,000 men refused to fight. Most of these men were pacifists, who believed that even during wartime it was wrong to kill another human being.

Alice Wheeldon, Willie Paul, John S. Clarke and Arthur McManus, established a network in Derby to help those conscientious objectors on the run or in jail. This included her son, William Wheeldon, who was secretly living with his sister, Winnie Mason, in Southampton.

On 27th December 1916, Alex Gordon arrived at Alice's house claiming to be a conscientious objectors on the run from the police. Alice arranged for him to spend the night at the home of Lydia Robinson. a couple of days later Gordon returned to Alice's home with Herbert Booth, another man who he said was a member of the anti-war movement. In fact, both Gordon and Booth were undercover agents working for MI5 via the Ministry of Munitions. According to Alice, Gordon and Booth both told her that dogs now guarded the camps in which conscientious objectors were held; and that they had suggested to her that poison would be necessary to eliminate the animals, in order that the men could escape.

Alice Wheeldon agreed to ask her son-in-law, Alfred Mason, who was a chemist in Southampton, to obtain the poison, as long as Gordon helped her with her plan to get her son to the United States: "Being a businesswoman I made a bargain with him (Gordon) that if I could assist him in getting his friends from a concentration camp by getting rid of the dogs, he would, in his turn, see to the three boys, my son, Mason and a young man named MacDonald, whom I have kept, get away."

On 31st January 1917, Alice Wheeldon, Hettie Wheeldon, Winnie Mason and Alfred Mason were arrested and charged with plotting to murder the British Prime Minister David Lloyd George and Arthur Henderson, the leader of the Labour Party.

At Alice's home they found Alexander Macdonald of the Sherwood Foresters who had been absent without leave since December 1916. When arrested Alice claimed: "I think it is a such a trumped-up charge to punish me for my lad being a conscientious objector... you punished him through me while you had him in prison... you brought up an unfounded charge that he went to prison for and now he has gone out of the way you think you will punish him through me and you will do it."

Sir Frederick Smith, the Attorney-General, was appointed as prosecutor of Alice Wheeldon. Smith, the MP for Liverpool Walton, had previously been in charge of the government's War Office Press Bureau, which had been responsible for newspaper censorship and the pro-war propaganda campaign.

The case was tried at the Old Bailey instead of in Derby. According to friends of the accused, the change of venue took advantage of the recent Zeppelin attacks on London. As Nicola Rippon pointed out in her book, The Plot to Kill Lloyd George (2009): "It made for a prospective jury that was likely to be both frightened of the enemy and sound in their determination to win the war."

The trial began on 6th March 1917. Alice Wheeldon selected Saiyid Haidan Riza as her defence counsel. He had only recently qualified as a lawyer and it would seem that he was chosen because of his involvement in the socialist movement.

In his opening statement Sir Frederick Smith argued that the "Wheeldon women were in the habit of employing, habitually, language which would be disgusting and obscene in the mouth of the lowest class of criminal." He went on to claim that the main evidence against the defendants was from the testimony of the two undercover agents. However, it was disclosed that Alex Gordon would not be appearing in court to give his evidence.

Basil Thomson, the Deputy Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, argued in his book, The Story of Scotland Yard (1935) that Gordon was an agent who "was a person with a criminal history, or he had invented the whole story to get money and credit from his employer."

Herbert Booth said in court that Alice Wheeldon had confessed to him that she and her daughters had taken part in the arson campaign when they were members of the Women's Social and Political Union. According to Booth, Alice claimed that she used petrol to set fire to the 900-year-old church of All Saints at Breadsall on 5th June 1914. She added: "You know the Breadsall job? We were nearly copped but we bloody well beat them!"

Booth also claimed on another occasion, when speaking about David Lloyd George and Arthur Henderson she remarked: "I hope the buggers will soon be dead." Alice added that Lloyd George had been "the cause of millions of innocent lives being sacrificed, the bugger shall be killed to stop it... and as for that other bugger Henderson, he is a traitor to his people." Booth also claimed that Alice made a death-threat to Herbert Asquith who she described as "the bloody brains of the business."

Herbert Booth testified that he asked Alice what the best method was to kill David Lloyd George. She replied: "We (the WSPU) had a plan before when we spent £300 in trying to poison him... to get a position in a hotel where he stayed and to drive a nail through his boot that had been dipped in the poison, but he went to France, the bugger."

Sir Frederick Smith argued that the plan was to use this method to kill the prime minister. He then produced letters in court that showed that Alice had contacted Alfred Mason and obtained four glass phials of poison that she gave to Booth. They were marked A, B, C and D. Later scientific evidence revealed the contents of two phials to be forms of strychnine, the others types of curare. However, the leading expert in poisons, Dr. Bernard Spilsbury, under cross-examination, admitted that he did not know of a single example "in scientific literature" of curate being administered by a dart.

Major William Lauriston Melville Lee, the head of the PMS2, who employed Herbert Booth and Alex Gordon, gave evidence in court. He was asked by Saiyid Haidan Riza if Gordon had a criminal record. He refused to answer this question and instead replied: "I have already already explained to you that I do not know the man. I cannot answer questions on matters beyond my own knowledge." He admitted he had instructed Booth to "get in touch with people who might be likely to commit sabotage".

Alice Wheeldon turned the jury against her when she refused to swear on the Bible. The judge responded by commenting: "You say that an affirmation will be the only power binding upon your conscience?" The implication being that the witness, by refusing to swear to God, would be more likely to be untruthful in their testimony." This was a common assumption held at the time. However, to Alice, by openly stating that she was an atheist, was her way of expressing her commitment to the truth.

Alice admitted that she had asked Alfred Mason to obtain poison to use on dogs guarding the camps in which conscientious objectors were held. This was supported by the letter sent by Mason that had been intercepted by the police. It included the following: "All four (glass phials) will probably leave a trace but if the bloke who owns it does suspect it will be a job to prove it. As long as you have a chance to get at the dog I pity it. Dead in 20 sec. Powder A on meat or bread is ok."

She insisted that Gordon's plan involved the killing of the guard dogs. He had told her that he knew of at least thirty COs who had escaped to America and that he was particularly interested in "five Yiddish still in the concentration camp." Gordon also claimed he had helped two other Jewish COs escape from imprisonment.

Alice Wheeldon admitted that she had told Alex Gordon that she hoped David Lloyd George and Arthur Henderson would soon be dead as she regarded them as "a traitor to the labouring classes?" However, she was certain that she had not said this when she handed over the poison to Gordon.

When Hettie Wheeldon gave evidence she claimed that It was Gordon and Booth who suggested that they assassinate the prime minister. She replied: "I said I thought assassination was ridiculous. The only thing to be done was to organise the men in the work-shops against compulsory military service. I said assassination was ridiculous because if you killed one you would have to kill another and so it would go on."

Hettie said that she was immediately suspicious of her mother's new friends: "I thought Gordon and Booth were police spies. I told my mother of my suspicions on 28 December. By the following Monday I was satisfied they were spies. I said to my mother: "You can do what you like, but I am having nothing to do with it."

In court Winnie Mason admitted having helped her mother to obtain poison, but insisted that it was for "some dogs" and was "part of the scheme for liberating prisoners for internment". Her husband, Alfred Mason, explained why he would not have supplied strychnine to kill a man as it was "too bitter and easily detected by any intended victim". He added that curare would not kill anything bigger than a dog.

Emmeline Pankhurst, the leader of the Women's Social and Political Union, told the court: "We (the WSPU) declare that there is no life more valuable to the nation than that of Mr Lloyd George. We would endanger our own lives rather than his should suffer."

Saiyid Haidan Riza argued that this was the first trial in English legal history to rely on the evidence of a secret agent. As Nicola Rippon pointed out in her book, The Plot to Kill Lloyd George (2009): "Riza declared that much of the weight of evidence against his clients was based on the words and actions of a man who had not even stood before the court to face examination." Riza argued: "I challenge the prosecution to produce Gordon. I demand that the prosecution shall produce him, so that he may be subjected to cross-examination. It is only in those parts of the world where secret agents are introduced that the most atrocious crimes are committed. I say that Gordon ought to be produced in the interest of public safety. If this method of the prosecution goes unchallenged, it augurs ill for England."

The judge disagreed with the objection to the use of secret agents. "Without them it would be impossible to detect crimes of this kind." However, he admitted that if the jury did not believe the evidence of Herbert Booth, then the case "to a large extent fails". Apparently, the jury did believe the testimony of Booth and after less than half-an-hour of deliberation, they found Alice Wheeldon, Winnie Mason and Alfred Mason guilty of conspiracy to murder. Alice was sentenced to ten years in prison. Alfred got seven years whereas Winnie received "five years' penal servitude."

The Derby Mercury reported: "It was a lamentable case, lamentable to see a whole family in the dock; it was sad to see women, apparently of education, using language which would be foul in the mouths of the lowest women. Two of the accused were teachers of the young; their habitual use of bad language made one hesitate in thinking whether education was the blessing we had all hoped."

On 13th March, three days after the conviction, the Amalgamated Society of Engineers, published an open letter to the Home Secretary that included the following: "We demand that the Police Spies, on whose evidence the Wheeldon family is being tried, be put in the Witness Box, believing that in the event of this being done fresh evidence will be forthcoming which will put a different complexion on the case."

Basil Thomson, the Deputy Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, was also unconvinced by the guilt of Alice Wheeldon and her family. Thomson later said that he had "an uneasy feeling that he himself might have acted as what the French call an agent provocateur - an inciting agent - by putting the idea into the woman's head, or, if the idea was already there, by offering to act as the dart-thrower."

Alice was sent to Aylesbury Prison where she began a campaign of non-cooperation with intermittent hunger strikes. One of the doctors at the prison reported that many prisoners were genuinely frightened of Alice who seemed to "have a devil" within her. However, the same doctor reported that she also had many admirers and had converted several prisoners to her revolutionary political ideas.

Some members of the public objected to Alice Weeldon being forced to eat. Mary Bullar wrote to Herbert Samuel, the Home Secretary and argued: "Could you not bring in a Bill at once simply to say that forcible feeding was to be abandoned - that all prisoners alike would be given their meals regularly and that it rested with them to eat them or not as they chose - it was the forcible feeding that made the outcry so there could hardly be one at giving it up!"

Alice was moved to Holloway Prison. As she was now separated from her daughter, Winnie Mason, she decided to go on another hunger strike. On 27th December 1917, Dr Wilfred Sass, the deputy medical officer at Holloway, reported that Alice's condition was rapidly declining: "Her pulse is becoming rather more rapid... of poor volume and rather collapsing... the heart sounds are rapid... at the apex of the heart." It was also reported that she said she was "going to die and that there would be a great row and a revolution as the result."

Winnie Mason wrote to her mother asking her to give up the hunger strike: "Oh Mam, please don't die - that's all that matters... you were always a fighter but this fight isn't worth your death... Oh Mam, for one kiss from you! Oh do get better please do, live for us all again."

On 29th December David Lloyd George sent a message to the Home Office that he had "received several applications on behalf of Mrs Wheeldon, and that he thought on no account should she be allowed to die in prison." Herbert Samuel was reluctant to take action but according to the official papers: "He (Lloyd George) evidently felt that, from the point of view of the government, and in view especially of the fact that he was the person whom she conspired to murder, it was very undesirable that she should die in prison."

Alice Wheeldon was told she was to be released from prison because of the intervention of the prime minister. She replied: "It was very magnanimous of him... he has proven himself to be a man." On 31st December, Hettie Wheeldon took her mother back to Derby.

Sylvia Pankhurst, writing in the Workers' Dreadnought, claimed that Alice was "mothering half a dozen other comrades with warm hospitality in a delightful old-fashioned household, where comfort was secured by hard work and thrifty management." She added that Alice was forced to close her shop but had "made the best of the situation by using her shop window for growing tomatoes."

The campaign continued to get Winnie Mason and Alfred Mason released from prison. On 26th January 1919 it was announced that the pair had be allowed out on licence at the request of Premier Lloyd George."

Alice Wheeldon's health never recovered from her time in prison. She died of influenza on 21st February 1919. At Alice's funeral, her friend John S. Clarke, made a speech that included the following: "She was a socialist and was enemy, particularly, of the deepest incarnation of inhumanity at present in Great Britain - that spirit which is incarnated in the person whose name I shall not insult the dead by mentioning. He was the one, who in the midst of high affairs of State, stepped out of his way to pursue a poor obscure family into the dungeon and into the grave... We are giving to the eternal keeping of Mother Earth, the mortal dust of a poor and innocent victim of a judicial murder."

Hettie Wheeldon, Winnie Mason and Alice Wheeldon.

On this day in 1917 C. P. Scott, recorded in his diary comments made by David Lloyd George at a private meeting. Scott the owner of the Manchester Guardian, initially opposed Britain's involvement in the First World War. Scott supported his friends, John Burns, John Morley and Charles Trevelyan, when they resigned from the government over this issue. As he wrote at the time: "I am strongly of the opinion that the war ought not to have taken place and that we ought not to have become parties to it, but once in it the whole future of our nation is at stake and we have no choice but do the utmost we can to secure success."

During the summer of 1914 most of the newspaper's writers, including C. E. Montague, Leonard Hobhouse, Herbert Sidebottom, Henry Nevinson, and J. A. Hobson had called for Britain to remain neutral in the growing conflict in Europe. However, once war was declared, most gave their support to the government. Montague although forty-seven with a wife and seven children, volunteered to join the British Army. Grey since his early twenties, Montague died his hair in an attempt to persuade the army to take him. On 23rd December, 1914, the Royal Fusiliers accepted him and he joined the Sportsman's Battalion.

Montague was later promoted to the rank of second lieutenant and transferred to Military Intelligence. For the next two years he had the task of writing propaganda for the British Army and censoring articles written by the five authorized English journalists on the Western Front (Perry Robinson, Philip Gibbs, Percival Phillips, Herbert Russell and Bleach Thomas). Howard Spring, another of the newspaper's writers, also worked for the Military Intelligence in France.

Henry Nevinson, the newspaper's main war reporter, was highly critical of the tactics used by the British Army but was unable to get this view past the censors. C. P. Scott and Leonard Hobhouse opposed conscription introduced in 1916 and the following year supported attempts made by Arthur Henderson to secure a negotiated peace.

On 27th December, Scott wrote in his diary that David Lloyd George told him : "I listened last night, at a dinner given to Philip Gibbs on his return from the front, to the most impressive and moving description from him of what the war (on the Western Front) really means, that I have heard. Even an audience of hardened politicians and journalists were strongly affected. If people really knew, the war would be stopped tomorrow. But of course they don't know, and can't know. The correspondents don't write and the censorship wouldn't pass the truth. What they do send is not the war, but just a pretty picture of the war with everybody doing gallant deeds. The thing is horrible and beyond human nature to bear and I feel I can't go on with this bloody business."

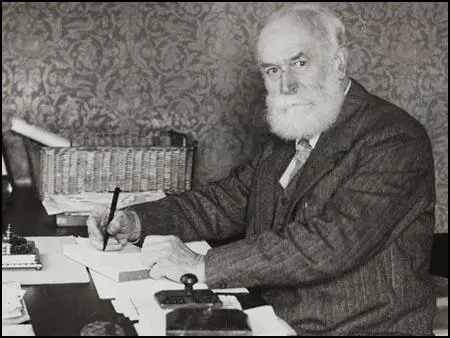

On this day in 1929 Joseph Stalin makes a speech on collectivization of agriculture. In 1926 Stalin formed an alliance with Nikolay Bukharin, Mikhail Tomsky and Alexei Rykov, on the right of the party, who wanted an expansion of the New Economic Policy that had been introduced several years earlier. Farmers were allowed to sell food on the open market and were allowed to employ people to work for them. Those farmers who expanded the size of their farms became known as kulaks. Bukharin believed the NEP offered a framework for the country's more peaceful and evolutionary "transition to socialism" and disregarded traditional party hostility to kulaks.

This move upset those on the left of the party such as Leon Trotsky, Lev Kamenev and Gregory Zinoviev. According to Robert Service, the author of Stalin: A Biography (2004): "Stalin and Bukharin rejected Trotsky and the Left Opposition as doctrinaires who by their actions would bring the USSR to perdition... Zinoviev and Kamenev felt uncomfortable with so drastic a turn towards the market economy... They disliked Stalin's movement to a doctrine that socialism could be built in a single country - and they simmered with resentment at the unceasing accumulation of power by Stalin."

On 27th December, 1929, Stalin said: "Our large-scale, centralised, socialist industry is developing according to the Marxist theory of expanded reproduction; for it is growing in volume from year to year, it has its accumulations and is advancing with giant strides. But our large-scale industry does not constitute the whole of the national economy. On the contrary, small-peasant economy still predominates in it. Can we say that our small-peasant economy is developing according to the principle of expanded reproduction? No, we cannot. Not only is there no annual expanded reproduction in the bulk of our small-peasant economy, but, on the contrary, it is seldom able to achieve even simple reproduction. Can we advance our socialised industry at an accelerated rate while we have such an agricultural basis as small-peasant economy, which is incapable of expanded reproduction, and which, in addition, is the predominant force in our national economy? No, we cannot. Can Soviet power and the work of socialist construction rest for any length of time on two different foundations: on the most large-scale and concentrated socialist industry, and the most disunited and backward, small-commodity peasant economy? No, they cannot. Sooner or later this would be bound to end in the complete collapse of the whole national economy."

On this day in 1938 the poet Osip Mandelstam died in a Soviet prison. Mandelstam was hostile to the Communist government and his poetry never conformed to the official doctrine of Socialist Realism. His work became increasingly hostile to the government of Joseph Stalin. During a holiday in Crimea he witnessed the result of Stalin's collectivisation programme.

In 1934 Mandelstam wrote an epigram about Stalin: His fingers are fat as grubs and the words, final as lead weights, fall from his lips... His cockroach whiskers leer and his boot tops gleam... the murderer and peasant slayer". It has been described as as a "sixteen line death sentence." Mandelstam was arrested and exiled to Cherdyn.

Mandelstam was allowed to return to Moscow in May, 1937. During the Great Purge, Mandelstam was attacked for his unwillingness to adopt Socialist Realism and he was accused of holding anti-Soviet views. In 1938 he was arrested and and charged with "counter-revolutionary activities" and was sentenced to five years in correction camps.

Nadezhda Khazina, his wife, later claimed: "The principles and aims of mass terror have nothing in common with ordinary police work or with security. The only purpose of terror is intimidation. To plunge the whole country into a state of chronic fear, the number of victims must be raised to astronomical levels, and on every floor of every building there must always be several apartments from which the tenants have suddenly been taken away. The remaining inhabitants will be model citizens for the rest of their lives - this was true for every street and every city through which the broom has swept. The only essential thing for those who rule by terror is not to overlook the new generations growing up without faith in their elders, and keep on repeating the process in systematic fashion."

Mandelstam wrote to his wife in October, 1938: "My health is very bad, I'm extremely exhausted and thin, almost unrecognizable, but I don't know whether there's any sense in sending clothes, food and money. You can try, all the same, I'm very cold without proper clothes." The Soviet government reported that Osip Mandelstam died at Vtoraya Rechka, on 27th December, 1938.

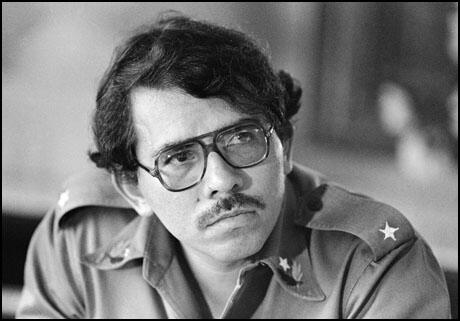

On this day in 1974, a group of FSLN guerrillas kidnapped a group of important figures close to President Anastasio Somoza. These men were later exchanged for Daniel Ortega and thirteen other Sandinista prisoners who were flown to Cuba.

The FSLN's prestige increased after this successful operation. In 1975 Anastasio Somoza ordered a violent and repressive campaign against the FSLN. It killed a large number of guerrillas including one of its founders, José Carlos Fonseca Amador.

Anastasio Somoza's regime received a set-back with the election of President Jimmy Carter in the United States. Carter announced he was only willing to provide aid to the government of Nicaragua if it improved its human rights record.

On 10th January, 1978, Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Cardenal, the publisher of the La Prensa newspaper and a strong opponent of the government, was assassinated. Evidence was uncovered that the publisher had been killed by Somoza's son and members of the National Guard. On 23rd January a nationwide strike began and the workers demanded an end to the military dictatorship.

In November 1978 the Organization of American States on Human Rights published a report charging the National Guard with numerous violations of human rights. The report was followed by a United Nations resolution condemning the Nicaraguan government.

Anastasio Somoza refused to leave office and various organizations, including the Sandinista National Liberation Front, Los Doce, the PLI, and the Popular Social Christian Party formed the National Patriotic Front. In June a provisional government in exile was established in Costa Rica. The FSLN continued its guerrilla activities and it gradually gained control of most of Nicaragua.

On 17th July, 1979, Anastasio Somoza resigned and fled to Paraguay. Daniel Ortega joined the Junta for National Reconstruction and in 1984 FSLN won the elections. The following year Ortega became president of Nicaragua.

Funded by the United States, the Contra rebels refused to accept the election of Ortega. His government's power also suffered from economic sanctions imposed by President Ronald Reagan. It was later discovered that the United States had attempted to damage the economy by the mining of Nicaragua's harbours.

In the 1990 elections the FSLN lost the elections to the UNO (Union of National Opposition). Ortega was replaced as president by Violeta Chamorro. Ortega left office with the words: "We leave victorious because we Sandinistas have spilled blood and sweat not to cling to government posts, but to bring Latin America a little dignity, a little social justice."