On this day on 19th April

On this day in 1791 Richard Price died. His funeral was conducted at Bunhill Fields and his funeral sermon was preached by Joseph Priestley.

Richard Price, the son of Rice Price, a Congregational minister, was born in Tynton, Glamorgan. From an early age he appears to have rejected his father's religious opinions and instead was attracted to the views of more liberal theologians.

Price attended a Dissenting Academy in London and afterwards became a chaplain in Stoke Newington. In 1756 he married Sarah Blundell and two years later moved to Newington Green, a small village near Hackney.

In 1758 Price wrote the very influential Review of the Principal Questions of Morals. In the book Price argued that individual conscience and reason should be used when making moral choices. Price also rejected the traditional Christian ideas of original sin and eternal punishment. Price and his friend, Joseph Priestley, became leaders of a group of men called Rational Dissenters.

Richard Price was also friendly with the mathematician Thomas Bayes. After Bayes's death in 1761, his relatives asked Price to examine his unpublished papers. Price realized their importance and submitted, An Essay Towards Solving a Problem in the Doctrine of Chances to the Royal Society. In this work, Price, using the information provided by Bayes, introduced the idea of estimating the probability of an event from the frequency of its previous occurrences.

In 1765 Price was admitted to the Royal Society for his work on probability. He also began collecting information on life expectation and in May 1770 he wrote to the Royal Society about the proper method of calculating the values of contingent reversions. It is believed that this information drew attention to the inadequate calculations on which many insurance and benefit societies had recently been formed.

Other books by Price include Observations on Reversionary Payments (1771), An Appeal to the Public on the Subject of the National Debt (1772) and Observations on the Nature of Civil Liberty, the Principles of Government, and the Justice and Policy of War with America (1776).

In 1784 Richard Price met Mary Wollstonecraft who had opened a school in Newington Green. Although Mary was brought up as an Anglican, she soon began attending Richard Price's chapel. Others who visited Price in Newington Green included John Howard, John Quincy Adams, Adam Smith and Benjamin Franklin. Price was a true libertarian and laboured throughout his life to increase intellectual, political and spiritual freedom for all people.

In November, 1789, Richard Price preached a sermon praising the French Revolution. Price argued that British people, like the French, had the right to remove a bad king from the throne. He told his congregation that he could "depart in peace, for mine eyes have seen Thy salvation."

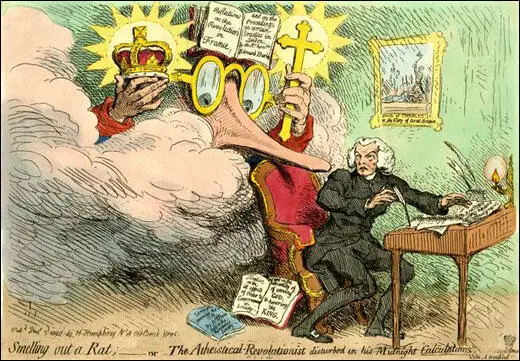

Edmund Burke, was appalled by this sermon and wrote a reply called Reflections on the Revolution in France, where he argued in favour of the inherited rights of the monarchy. James Gillray joined in the debate by producing a print, Smelling out a Rat (1790). It shows Richard Price seated in an armchair at a small writing-desk. Burke is represented by an enormous spectacled nose which rests on the back of Price's chair and by two gigantic hands, one holding a crown, the other a cross, both of which are surrounded by star-shaped haloes. The spectacles support (between the crown and the cross): "Reflections on the Revolution in France, and on the Proceedings in certain Societies in London, by the Rt honble Edmund Burke." Price's pen drops from his hand; the paper before him is headed "On the Benifits of Anarchy Regicide Atheism". The table is lit by a lamp with a naked flame and reflector. Against his chair leans an open book: "Treatise on the ill effects of Order & Government in Society, and on the absurdity of serving God, & honoring the King". On the wall above Price's head is a picture: "Death of Charles Ist or, the Glory of Great Britain". It shows the execution of Charles I.

Mary Wollstonecraft was upset by Burke's attack on her friend and she decided to defend him by writing a pamphlet A Vindication of the Rights of Man. In her pamphlet Wollstonecraft not only supported Price but also pointed out what she thought was wrong with society.

Price was attracted to the ideas of Jeremy Bentham. Price accepted many aspects of Bentham's unitarianism, especially his views on political libertarianism and his opposition to Christian orthodoxy. However, unlike other unitarians, Price was unwilling to question the divinity of Christ. In 1791 he became one of the original members of the Unitarian Society.

On this day in 1872 Philippa Strachey, the fifth among the ten children (five daughters and five sons) of Lieutenant-General Sir Richard Strachey (1817–1908) and his wife, Jane Grant Strachey (1840–1928), was born at Stowey House, Clapham Common, on 19th April, 1872. Amongst her brothers and sisters were Lytton Strachey, James Strachey and Oliver Strachey.

After visiting India to see her brothers she taught at an infant school. Her life changed after she met feminist Emily Davies. Under her influence she joined the London Society for Women's Suffrage. She was asked to organize the National Union of Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) march on 9th February 1907. It was such a success that she was given the task of organizing all subsequent NUWSS demonstrations and pageants.

Several members of the family were involved in the struggle for women's suffrage. This included her mother, sister-in-law, Rachel Strachey, and her cousin Duncan Grant, a member of the Men's League For Women's Suffrage. In 1909 she encouraged him to enter the Artists' Suffrage League (ASL) poster competition. Grant submitted Handicapped! and shared the first prize of £5. The Common Cause newspaper described it as depicting "a stalwart Grace Darling type struggling in the trough of a heavy sea with only a pair of sculls, while a nonchalant young man in flannels glides gaily by, with a wind inflating his sail - the vote - treating with good temper a subject which often causes bitterness."

According to Barbara Caine: "A woman of considerable wit and charm, Pippa Strachey was a gifted and stylish correspondent and a great raconteuse. She preferred the backroom role of organizing secretary to any more public position, hating the limelight and speaking in public very rarely."

Strachey was a strong supporter of the British government during the First World War. This involved her organizing the Women's Service, which both found work for women and trained them as substitutes for men in many skilled occupations. After the war she continued to concentrate on women's employment, through the London Society for Women's Service, that continued to campaign for the vote for all women.

Strachey also chaired the advisory committee of the Women's Employment Federation, was an adviser to the Cambridge University Women's Employment Committee, and supported both the Joint Committee for Women in the Civil Service and the Society for Promoting the Training of Women. She served for many years on the board of Bedford College, London. A devoted admirer of Millicent Garrett Fawcett, she played a major role in establishing the Fawcett Society.

Philippa Strachey lost her sight but in her nineties she taught herself braille She died, unmarried, on 23 August 1968 at 38 Carlton Drive, Putney.

On this day in 1881 Benjamin Disraeli died aged 76. In the 1880 General Election the Liberal Party won 352 seats with 54.7% of the vote. Benjamin Disraeli resigned and Queen Victoria invited Spencer Cavendish, Lord Hartington, the official leader of the party, to become her new prime minister. He replied that the Liberal majority appeared to the nation as being a "Gladstone-created one" and that Gladstone had already told other senior figures in the party he was unwilling to serve under anybody else.

Victoria explained to Hartington that "there was one great difficulty, which was that I could not give Mr. Gladstone my confidence." She told her private secretary, Sir Henry Frederick Ponsonby: "She will sooner abdicate than send for or have any communication with that half mad firebrand who would soon ruin everything and be a dictator. Others but herself may submit to his democratic rule but not the Queen."

Victoria now asked to see Granville Leveson-Gower, 2nd Earl Granville. He also refused to be prime minister, explaining that Gladstone had a "great amount of popularity at the present moment amongst the people". He also suggested that Gladstone, now aged 70, would probably retire by 1881. Victoria now agreed to appoint Gladstone as her prime minister. That night he recorded in his diary that the Queen received him "with the perfect courtesy from which she never deviates".

Benjamin Disraeli decided to retire from politics. Disraeli hoped to spend his retirement writing novels but soon after the publication of Endymion (1880) he became very ill with severe bronchitis. Queen Victoria wanted to visit Disraeli but he rejected the idea. He is said to have remarked: "No it is better not. She would only ask me to take a message to Prince Albert".

On this day in 1882 suffragist Margery Corbett, the daughter of Charles Corbett and Marie Corbett, was born at Danehill, Sussex. Margery and her younger sister, Cicely Corbett, were educated at home by Lina Eckenstein. Charles taught the girls classics, history and mathematics and Marie taught them scripture and the piano. A local woman gave them lessons in French and German.

For many years Charles Corbett and Marie Corbett made public speeches on the subject of women's rights in East Grinstead High Street. East Grinstead was a safe Conservative seat and the crowds were usually very hostile. A survey carried out in 1911 suggested that less than 20% of the women in East Grinstead supported women having the vote in parliamentary elections. In her autobiography, Margery described how the people of East Grinstead reacted to her parents support of women's rights: "My parents were Liberals… at that period as much hated and distrusted by the gentry as Communists are today, and regarded as traitors to their class. In consequence they boycotted them… I suspect this boycott threw my energetic mother even more fervently into good works amongst the villagers, where, in the days before the welfare state, poverty was widespread."

At the age of eighteen, Margery and her younger sister Cicely and a group of friends formed a society called the Younger Suffragists. In 1901 Margery won a place at Newnham College, Cambridge to read Classics. At university she joined the Cambridge branch of the National Union of Women Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) and by the time she was nineteen she had become secretary of the Constitutional Suffrage Movement.

Her friend, Mary Hamilton, explained: "At college Margery was intensely keen on civil liberties, free trade, international good will, democracy… She spends time and energy without stint or personal ambition… She has an immense sense of duty, and must have spent a very large part of her entire life on committees and at meetings."

Although Margery Corbett passed her examinations, because she was a woman, Cambridge University refused to grant her a degree (Cambridge University granted the first degrees to women in 1947). In 1904 Margery obtained a place at the Cambridge Teachers Training College but after completing the course she decided that teaching was not for her.

In 1907 Margery Corbett was appointed Secretary of the National Union of Women Suffrage Societies and was giving the responsibility of editing their journal. Disappointed with the poor record of the Liberal Party with respect to women's suffrage, Margery left the Women's Liberal Federation and with her mother and sister helped form the Liberal Suffrage Group. Margery also played an active role in the by-election where Bertrand Russell unsuccessfully stood as the women's suffrage candidate. The following year Margery became a member of the National Committee of the NUWSS.

In 1909 Margery became involved in the International Woman Suffrage Alliance and was a speaker at their conferences in Berlin and Stockholm. Margery married the barrister, Brian Ashby in 1910. In November 1914, Margery gave birth to her only child. This restricted her activities during the next few years but she was to do war work in hospitals and on the land. Margery also ran a canteen at an outbuilding of Woodgate, in an attempt to provide good food for local schoolchildren.

After the passing of the Qualification of Women Act in 1918 Margery Corbett Ashby became one of the seventeen women candidates that stood in the post-war election. Margery was the Liberal candidate for Ladywood, Birmingham. During the election campaign Margery advocated feminist policies that would have given women full political equality with men. This was the first of seven unsuccessful attempts by Margery Corbett Ashby to get into the House of Commons.

In 1919 Margery was a member of the International Alliance of Women who attended the Versailles Peace Conference. The following year she took part in the first post-war congress of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance. In 1923 she was elected president of the organisation and she held the post until her retirement in 1946.

In 1932 she was the British delegate to the Geneva Disarmament Conference. Margery resigned from this position in 1935 in protest at the British government's refusal to support any practical scheme for mutual security and defence. In 1937 she was one of the signatories of as declaration in the press asserting that war could be avoided if the League of Nations took positive action. She was also president of the National Union for Equal Citizenship.

Margery continued to be active in politics after the Second World War. In 1952, at the age of seventy, she became editor of International Women's News. Margery continued to be active in politics and was probably the only woman in Britain to be involved in suffrage campaign before the First World War and the Women's Liberation Movement in the 1970s. Margery's last political demonstration was at the age of ninety-eight when she took part in the Women's Day of Action in London. Margery Corbett Ashby died at Danehill on 22nd May 1981.

On this day in 1893 Jessie Stephen, the eldest of eleven children of Alexander Stephen, tailor, and his wife, Jane Miller, was born in Marylebone, London. When she was a child her family moved to Edinburgh. Later, they settled in Dunfermline.

In 1901 her father found work for the Co-operative Society in Glasgow. Jessie was educated at North Kelvinside School. At fourteen she won a scholarship, but had to leave school a year later because of her father's unemployment. Jessie found work as a domestic servant.

Jessie, a committed socialist, joined the Maryhill branch of the Independent Labour Party (ILP). In 1912 she started organizing maidservants in Glasgow into a domestic workers' union branch. The following year she helped establish the formation of the Scottish Federation of Domestic Workers.

Jessie Stephen was also an active member of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). In 1912 the WSPU began a campaign to destroy the contents of pillar-boxes. By December, the government claimed that over 5,000 letters had been damaged by the WSPU. According to her biographer, Audrey Canning: "Jessie was assigned to drop acid into local pillar boxes. while dressed in her maid's uniform. As a working-class suffragette, she enlisted the support of dockers in the ILP to deal with hecklers at WSPU meetings." In March 1913 was the youngest of a delegation of Glasgow working-women who went to London to lobby the House of Commons.

On 4th August, 1914, England declared war on Germany. The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort.

Emmeline Pankhurst announced that all militants had to "fight for their country as they fought for the vote." Ethel Smyth pointed out in her autobiography, Female Pipings for Eden (1933): "Mrs Pankhurst declared that it was now a question of Votes for Women, but of having any country left to vote in. The Suffrage ship was put out of commission for the duration of the war, and the militants began to tackle the common task."

Jessie Stephen disagreed with this strategy and after leaving the WSPU joined the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELF), an organisation that combined socialism with a demand for women's suffrage, it also worked closely with the Independent Labour Party. Other members included Sylvia Pankhurst, Keir Hardie, Julia Scurr, Mary Phillips, Millie Lansbury, Eveline Haverfield, Maud Joachim, Lilian Dove-Wilcox, Nellie Cressall and George Lansbury. In the early stages of the war Jessie toured northern England to raise funds and sell the federation's journal, the The Women's Dreadnought.

In March 1916 Sylvia Pankhurst renamed the East London Federation of Suffragettes, the Workers' Suffrage Federation (WSF). The newspaper was renamed the Workers' Dreadnought and continued to campaign against the war and gave strong support to organizations such as the Non-Conscription Fellowship. The newspaper also published the famous anti-war statement by Siegfried Sassoon.

Audrey Canning has argued that: "Tall, black-haired, and handsome as a young woman, Jessie Stephen had a strong personality and excelled as a lively speaker... She attributed her vocal powers to two years' training as a contralto at the London Guildhall School of Music and enjoyed entertaining her English audiences to recitals of Hebridean folk-songs."

In 1917 Jessie Stephen became the Independent Labour Party organizer for Bermondsey, where she worked closely with ILP leader, Alfred Salter. The anti-war stance of Salter resulted in a loss of support for this left-wing member of the party. Salter wrote: "For a while it seemed as if the whole fabric of our organisation so laboriously built up in the past years, was doomed to go under."

Jessie Stephen had developed a good reputation for effective campaigning and Mary Macarthur recruited her to work for the National Federation of Women Workers. In December 1918 Jessie became secretary of its domestic workers' section. The following year she was appointed vice-chair of the catering trade for the new Ministry of Reconstruction. In 1919 she was elected to Bermondsey Borough Council.

Under the leadership of Ada Salter, London's first woman Mayor. As a socialist she declined to wear Mayoral robes or the chain of office. With a Labour majority on the council, Ada could now push on with her plans to improve the look of Bermondsey. A Borough Gardens Superintendent was employed and ordered to plant elms, populars, planes and acacias in the streets of Bermondsey. Later he added birch, ash, yew and wild cherry.

Jessie Stephen also became involved in the campaign to improve public health in Bermondsey. Special films were prepared and were shown to large crowds in the open air and pamphlets were distributed throughout the borough. A systematic house-to-house inspection was conducted to seek out conditions dangerous to health. Premises where food was sold were constantly examined and samples of foods were taken away for analysis.

During the 1926 General Strike Jessie agreed on explaining the trade union position in a tour of the United States. Speaking to large gatherings of immigrant workers from Europe, she raised substantial funds for the National Union of Mineworkers and the Socialist Party of America. She also visited where she encouraged the formation of the Canadian Union of Domestic Workers.

According to her biographer, Audrey Canning: "Besides having a talent for journalism Jessie Stephen also proved adept at running her own secretarial agency and joined the National Union of Clerks in 1938. In 1944 she was appointed as the first woman area union organizer of the National Clerical and Administrative Workers' Union for south Wales and the west of England, moving to Bristol, where she became the first woman president of the trades council and a city councillor in 1952. Jessie Stephen established close connections with the Bristol Co-operative Society after 1948, both as employee - working for eleven years with Broad Quay branch of the Co-operative Wholesale Society - and as chair of the management committee."

Jessie Stephen died at Bristol General Hospital aged eighty-six on 12th June 1979 from pneumonia and heart failure.

On this day in 1894 Elizabeth Kirkpatrick was born in Chicago, Illinois. Her father, Dr. L. Kirkpatrick, was a physician. She attended a Catholic girls' school before studying music at the University of Chicago. She failed to graduate and married Albert Dilling, an engineer, in 1918.

Elizabeth Dilling had two children, Kirkpatrick and Elizabeth Jane. In 1931 they visited the Soviet Union. Dilling later recalled: "Our family trip to Red Russia in 1931 started my dedication to anti-Communism. We were taken behind the scenes by friends working for the Soviet Government and saw deplorable conditions, first hand. We were appalled, not only at the forced labor, the squalid crowded living quarters, the breadline ration card workers' stores, the mothers pushing wheelbarrows and the begging children of the State nurseries besieging us. The open virulent anti-Christ campaign, everywhere, was a shock. In public places were the tirades by loud speaker, in Russian (our friends translated). Atheist cartoons representing Christ as a villain, a drunk, the object of a cannibalistic orgy (Holy Communion); as an oppressor of labor; again as trash being dumped from a wheelbarrow by the Soviet Five-Year-Plan - these lurid cartoons filled the big bulletin boards in the churches our Soviet guides took us to visit." When she returned to America she went on a lecture tour where she expressed her hostility to communism.

In 1934 Dilling published The Red Network: A Who's Who of Radicalism for Patriots (1934). This included attacks on several well-known figures on the left. For example she said of Jane Addams: "Greatly beloved because of her kindly intentions toward the poor, Jane Addams has been able to do more probably than any other living woman to popularize pacifism and to introduce radicalism into colleges, settlements, and respectable circles. The influence of her radical proteges, who consider Hull House their home center, reaches out all over the world. One knowing of her consistent aid of the Red movement can only marvel at the smooth and charming way she at the same time disguises this aid." Other people smeared by Dilling included Albert Einstein who she pointed out was "married to Russian" and had his property confiscated by the Nazis because he was a communist (this was untrue). Frederic C. Howe, Franz Boas, Sigmund Freud and Mahatma Gandhi, were also accused of being communists.

Her next book was an attack on President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal entitled The Roosevelt Red Record and Its Background (1936). Dilling argued that officials in Roosevelt's administration were associated with members of the American Communist Party. She also claimed that Eleanor Roosevelt was a "socialist sympathizer and associate, pacifist". During this period she became associated with Father Charles Coughlin.

Dilling joined forces with Robert E. Wood, John T. Flynn, Charles A. Lindbergh, Burton K. Wheeler, Robert R. McCormick, Hugh Johnson, Robert LaFollette Jr., Amos Pinchot, Hamilton Stuyvesan Fish, Harry Elmer Barnes and Gerald Nye to form the America First Committee (AFC) in September 1940. The AFC had four main principles: (1) The United States must build an impregnable defense for America; (2) No foreign power, nor group of powers, can successfully attack a prepared America; (3) American democracy can be preserved only by keeping out of the European War; (4) "Aid short of war" weakens national defense at home and threatens to involve America in war abroad.

Dilling's writing became increasingly anti-Semitic. In The Octopus (1940), which she wrote under the pseudonym Rev. Frank Woodruff Johnson, she attacked the Jewish Anti-Defamation League and linked Jews to communism. She was also active in two other anti-Semitic organisations, Mothers' Peace Movement and We the Mothers Mobilize for America.

After the Pearl Harbor attack, Dilling was indicted, along with 28 others, under the The Alien Registration Act (also known as the Smith Act) that made it illegal for anyone in the United States to advocate, abet, or teach the desirability of overthrowing the government. The defendants were accused of holding pro-fascist views. Attempts were made to prove they were Nazi propaganda agents by demonstrating the similarity between their statements and enemy propaganda. The case finally ended in a mistrial after the death of the presiding judge, Edward C. Eicher. As a result of protests led by Roger Baldwin of the American Civil Liberties Union, Dilling and in December 1946 the government withdrew the charges.

In the 1950s, Elizabeth Dilling was a contributor to several anti-Semitic journals. This included Common Sense , edited by Conde McGinley. She supported McGinley when he was successfully sued for libel by by Rabbi Joachim Prinz in 1955. Her son, Kirkpatrick Dilling, was one of his defence attorneys. The jury awarded Prinz $30,000, agreeing that the publication was lying when it falsely claimed that he was "expelled in 1937 from Germany for revolutionary communistic activities". Her second husband,

Jeremiah Stokes, shared her political views and was the co-author with Dilling of The Plot Against Christianity (1964). It included the following passage: "Marxism, Socialism, or Communism in practice are nothing but state-capitalism and rule by a privileged minority, exercising despotic and total control over a majority having virtually no property or legal rights. As is discussed elsewhere herein, Talmudic Judaism is the progenitor of modem Communism and Marxist collectivism as it is now applied to a billion or more of the world’s population. Only through thorough understanding of the ideology from which this collectivism originates, and those who dominate and propagate it, can the rest of the world hope to escape the same fate. Communism - Socialism was originated by Jews and has been dominated by them from the beginning." Elizabeth Dilling died on 26th May, 1966.

On this day in 1901 Edith Summerskill, the youngest daughter of Dr William Summerskill (1866–1947) and his wife, Edith Clara Wilde, was born in Doughty Street, London, on 19th April 1901. As a child she accompanied her father on home visits and he told her about the connections between poverty and ill-health. Dr. Summerskill held left-wing political views and was a strong supporter of women's suffrage.

Edith was educated at Eltham Hill Grammar School and in 1918 won a place at King's College, where she studied medicine. Trained at Charing Cross Hospital she qualified as a doctor in 1924. The following year she married Dr. Edward Jeffrey Samuel (1895–1983).

In 1928 Edith and her husband established a joint medical practice in North London. In an interview she gave to BBC Radio 4 many years later, she recalled attending her first confinement as a newly qualified doctor. Shocked at the state of the home and the undernourishment of the mother, whose first child had rickets, she said "In that room that night, I became a socialist".

In 1930 Dr Charles Brook met Dr Ewald Fabian, the editor of Der Sozialistische Arzt and the head of Verbandes Sozialistischer Aerzte in Germany. Fabian said he was surprised that Britain did not have an organisation that represented socialists in the medical profession. Brook responded by arranging a meeting to take place on 21st September 1930 at the National Labour Club. As a result it was decided to form the Socialist Medical Association. Brook was appointed as Secretary of the SMA and Somerville Hastings, the Labour MP for Reading, became the first President. Other early members included Edith Summerskill, Hyacinth Morgan, Reginald Saxton, Alex Tudor-Hart, Archie Cochrane, Christopher Addison, John Baird, Alfred Salter, Barnett Stross, Robert Forgan and Richard Doll.

The Socialist Medical Association agreed a constitution in November 1930, "incorporating the basic aims of a socialised medical service, free and open to all, and the promotion of a high standard of health for the people of Britain". The SMA also committed itself to the dissemination of socialism within the medical profession. The SMA was open to all doctors and members of allied professions, such as dentists, nurses and pharmacists, who were socialists and subscribed to its aims. International links were established through the International Socialist Medical Association, based in Prague, an organisation that had been established by Dr Ewald Fabian.

In 1931 the SMA, after representations from Somerville Hastings and Charles Brook, became affiliated to the Labour Party. The following year, at its annual party conference, a resolution calling for a national health service to be an immediate priority of a Labour government was passed. The SMA also launched The Socialist Doctor journal in 1932. Summerskill was an active member of the SMA and as John Stewart, the author of The Battle for Health: A Political History of the Socialist Medical Association (1999), has pointed out, "she put forward the case for a socialized health service, and it was she who came up with the idea of organizing social events both to raise money and to attract publicity to the organization."

Edith Summerskill, who was on the left-wing of the Labour Party, played an active role in supporting the Popular Front government during the Spanish Civil War. On 8th August 1936 it was decided to form a Spanish Medical Aid Committee. Dr. Christopher Addison was elected President and the Marchioness of Huntingdon agreed to become treasurer. Other supporters included Summerskill, Somerville Hastings, Charles Brook, Isabel Brown, Leah Manning, George Jeger, Philip D'Arcy Hart, Frederick Le Gros Clark, Lord Faringdon, Arthur Greenwood, George Lansbury, Victor Gollancz, D. N. Pritt, Archibald Sinclair, Rebecca West, William Temple, Tom Mann, Ben Tillett, Eleanor Rathbone, Julian Huxley, Harry Pollitt and Mary Redfern Davies. Summerskill was also involved in establishing The National Women's Appeal for Food for Spain.

John Stewart pointed out in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography that: "As a feminist, Summerskill paid particular attention to women's social and political issues. In the 1930s she was outspoken in her attacks on the prevailing high rate of maternal mortality and urged that the interests of the expectant mother must always be prioritized by the maternity services. She was especially critical of negligent doctors and inadequate provision, pointing out that a significant proportion of deaths in childbirth resulted from preventable, and hence unnecessary, infections. Unsurprisingly, this was related to broader claims for a publicly funded and administered health care service."

Summerskill was selected as the parliamentary candidate for Bury. In the 1935 General Election she was attacked by the Roman Catholic Church for her support for women's right to birth control. This contributed to her defeat and the following year she was was adopted as Labour Party candidate for the parliamentary constituency of Fulham West. Summerskill won the seat at a by-election in April 1938 and she now joined two other members of the SMA, Alfred Salter and Somerville Hastings, in the House of Commons. Later that year Summerskill was co-founder with Vera Brittain, Helena Normanton and Helen Nutting of the Married Women's Association. The organisation sought equal relationships between men and women in marriage.

During the Second World War the influence of Summerskill and the Socialist Medical Association increased. In October 1940, at the beginning of the Blitz, she told fellow MPs that the wartime organization of health services, and the impact of the war itself, had greatly and irreversibly changed the provision and perception of health care. Along with Somerville Hastings she was a member of Labour's advisory committee on public health, a body charged with formulating proposals for a national health service. In 1944 she became a member of Labour's national executive.

Summerskill was returned to the House of Commons at the 1945 General Election as MP for Fulham West. She was one of twelve SMA members elected and their was now a concerted effort to persuade the government to introduce a National Health Service. Hastings was considered too old to become Minister of Health but it was hoped that Clement Attlee would appoint another SMA member such as Edith Summerskill. However, Attlee rejected this advice and Aneurin Bevan was appointed instead.

Edith Summerskill was appointed as parliamentary secretary at the Ministry of Food. As John Stewart has pointed out: "This was always going to be a challenging position at a time of rationing and austerity - aspects of post-war life with which the British people were becoming increasingly disenchanted. Among her campaigns were those to make milk free from tuberculosis, an issue on which she could draw upon her medical knowledge."

In the 1950 Summerskill became minister of national insurance. However, she lost the post following Labour's defeat in the 1951 General Election. Over the next eight years she served on Labour's shadow cabinet. She was also a member of Labour's national executive and was party chairman in 1954–5. In 1956 was one of the platform speakers at Labour's famous Trafalgar Square rally against the Suez War.

In February 1961 Summerskill was made a life peeress. She was an active member of the House of Lords and her successful private member's bill, became the 1964 Married Women's Property Act. She also supported the reform of the law relating to homosexuality and for the legalization of abortion and campaigned against nuclear weapons and the American intervention in Vietnam. In 1967 she published her autobiography, A Woman's World.

Edith Summerskill died at her home in Millfield Lane, Highgate, on 4th February 1980.

On this day in 1943 Yitzhak Zuckerman leads the Warsaw Uprising. At the Wannsee Conference held on 20th January 1942, Reinhard Heydrich chaired a meeting to consider what to do with the large number of Jews under their control. Also at the meeting were Heinrich Muller, Adolf Eichmann and Roland Friesler.

Those at the meeting eventually decided on what became known as the Final Solution. From that date the extermination of the Jews became a systematically organized operation. It was decided to establish extermination camps in the east that had the capacity to kill large numbers including Belzec (15,000 a day), Sobibor (20,000), Treblinka (25,000) and Majdanek (25,000).

Between 22nd July and 3rd October 1942, 310,322 Jews were deported from the Warsaw ghetto to these extermination camps. Information got back to the ghetto what was happening to those people and it was decided to resist any further attempts at deportation. In January 1943, Heinrich Himmler gave instructions for Warsaw to be "Jew free" by Hitler's birthday on 20th April.

Warsaw contained several resistance groups. The largest was the Polish Home Army. There was also the Jewish Military Union and the communist Jewish Fighter Organization (ZOB) led by Mordechai Anielewicz, Yitzhak Zuckerman, Gole Mire and Adolf Liebeskind.

On 19th April 1943 the Waffen SS entered the Warsaw ghetto. Although they only had two machine-guns, fifteen rifles and 500 pistols, the Jews opened fire on the soldiers. They also attacked them with grenades and petrol bombs. The Germans took heavy casualties and the Warsaw military commander, Brigadier-General Jürgen Stroop, ordered his men to retreat. He then gave instructions for all the buildings in the ghetto to be set on fire.

As people fled from the fires they were rounded up and deported to the extermination camp at Treblinka. The ghetto fighters continued the battle from the cellars and attics of Warsaw. On 8th May the Germans began using poison gas on the insurgents in the last fortified bunker. About a hundred men and women escaped into the underground sewers but the rest were killed by the gas. It is believed that only 100 Jews survived the 1943 ghetto rising.

In the summer of 1944 the Red Army began to advance rapidly into German occupied Poland. The advancing Soviet troops refused to accept the authority of the Polish government-in-exile and disarmed members of the Polish Home Army they met during the invasion.

The Polish government-in-exile in London feared that the Soviet Union would replace Nazi Germany as occupiers of the country. On 26th July 1944 the Polish government secretly ordered General Tadeusz Komorowski, the commander of the Polish Home Army, to capture Warsaw before the arrival of the advancing Russians. Five days later Komorowski gave the orders to rise up.

The Home Army had about 50,000 soldiers in Warsaw. There were a further 1,700 people who were members of other Polish resistance groups who were willing to join the uprising. The men were desperately short of arms and ammunition. It is estimated they had 1,000 rifles, 300 automatic pistols, 60 sub-machine-guns, 35 anti-tank guns, 1,700 pistols and 25,000 grenades. The army also had its own workshop and were attempting to produce pistols, flame-throwers and grenades.

On the first day of the rising on 1st August, 1944, the Poles managed to capture part of the left bank of the River Vistula in Warsaw. However, attempts to take the bridges crossing the river were unsuccessful.

German reinforcements arrived on the 3rd August. The German Army used 600mm siege guns on Warsaw and the Luftwaffe bombed the city around-the-clock. British and Polish airmen flew in supplies from bases in Italy but it was difficult to drop the food and ammunition to places still in the hands of the rebels. The Royal Air Force and the Polish Air Force made 223 sorties and lost 34 aircraft during the uprising.

Heinrich Himmler gave instructions "that every inhabitant should be killed" and that Warsaw should "be razed to the ground" as an example to the rest of Europe under German occupation. As soon as territory was taken the Nazi's took revenge on the local people. In the Wola district alone an estimated 25,000 people were executed by firing squad.

When the Old Town was taken by the German Army on 2nd August, the Polish resistance fighters were forced to flee via the sewer canals. This network of underground canals were now used to move men and supplies under enemy controlled areas of Warsaw.

On 20th August the Polish Home Army captured the Polish Telephone Company building and the Krawkowskie Police Station. Three days later they took control of the Piusa Telephone Exchange.

On 10th September the Red Army led by Marshal Konstantin Rokossovy, entered the city but met heavy resistance. After five days Soviet forces had captured the right bank of the city. Rokossovy then halted his troops and waited for reinforcements. However, some historians have argued that Rokossovy was following the orders of Joseph Stalin, who wanted the Germans to destroy what was left of the Polish Home Army.

The insurgents were forced to leave Czerniakow on 23rd September. Three days later they were forced to leave the Upper Mokotow area via the underground sewers. On 30th September General Tadeusz Komorowski appointed General Leopold Okulicki as head of the Polish underground.

Running out of men and supplies General Komorowski and 15,000 members of the Polish Home Army were forced to surrender on 2nd October 1944. It is estimated that 18,000 insurgents were killed and another 6,000 were seriously wounded. A further 150,000 civilians were also killed during the uprising.

After the Polish surrender the German Army began to systematically to destroy the surviving buildings in Warsaw. By the time the Red Army resumed its attack on Warsaw, over 70 per cent of the city had been destroyed. Over the next few weeks the Soviet forces took control of the city.

On this day in 1945 Richard Dimbleby reports from Belsen concentration camp.

I picked my way over corpse after corpse in the gloom, until I heard one voice raised above the gentle undulating moaning. I found a girl, she was a living skeleton, impossible to gauge her age for she had practically no hair left, and her face was only a yellow parchment sheet with two holes in it for eyes. She was stretching out her stick of an arm and gasping something, it was "English, English, medicine, medicine", and she was trying to cry but she hadn't enough strength. And beyond her down the passage and in the hut there were the convulsive movements of dying people too weak to raise themselves from the floor.

In the shade of some trees lay a great collection of bodies. I walked about them trying to count, there were perhaps 150 of them flung down on each other, all naked, all so thin that their yellow skin glistened like stretched rubber on their bones. Some of the poor starved creatures whose bodies were there looked so utterly unreal and inhuman that I could have imagined that they had never lived at all. They were like polished skeletons, the skeletons that medical students like to play practical jokes with.

At one end of the pile a cluster of men and women were gathered round a fire; they were using rags and old shoes taken from the bodies to keep it alight, and they were heating soup over it. And close by was the enclosure where 500 children between the ages of five and twelve had been kept. They were not so hungry as the rest, for the women had sacrificed themselves to keep them alive. Babies were born at Belsen, some of them shrunken, wizened little things that could not live, because their mothers could not feed them.

One woman, distraught to the point of madness, flung herself at a British soldier who was on guard at the camp on the night that it was reached by the 11th Armoured Division; she begged him to give her some milk for the tiny baby she held in her arms. She laid the mite on the ground and threw herself at the sentry's feet and kissed his boots. And when, in his distress, he asked her to get up, she put the baby in his arms and ran off crying that she would find milk for it because there was no milk in her breast. And when the soldier opened the bundle of rags to look at the child, he found that it had been dead for days.

There was no privacy of any kind. Women stood naked at the side of the track, washing in cupfuls of water taken from British Army trucks. Others squatted while they searched themselves for lice, and examined each other's hair. Sufferers from dysentery leaned against the huts, straining helplessly, and all around and about them was this awful drifting tide of exhausted people, neither caring nor watching. Just a few held out their withered hands to us as we passed by, and blessed the doctor, whom they knew had become the camp commander in place of the brutal Kramer.

On this day in 1945 French resistance leader, Charles Delestraint, is executed in Dachau by the Schutz Staffeinel (SS). Charles Delestraint was born in France on 12th March 1879. A member of the French Army he spent most of the First World War as a prisoner of war.

He remained in the army and became a leading supporter of a modern army made up of armoured divisions. Delestraint retired in 1939 but was recalled to the armed services at the beginning of the Second World War and led the counter-attack against the German Army at Abbeville (3rd-4th June, 1940). After France surrendered Delestraint retired to Bourgen Bresse.

Delestraint was recruited to the French Resistance by Henry Frenay. After visiting Charles De Gaulle in London he agreed to head the Armée Secrete. Delestraint returned to France with Jean Moulin on 24th March 1943.

René Hardy, a member of the resistance had been arrested and turned and his information led to Delestraint being arrested by the Gestapo on 9th June, 1943. After being interrogated by Klaus Barbie he was deported to Nazi Germany.