On this day on 17th January

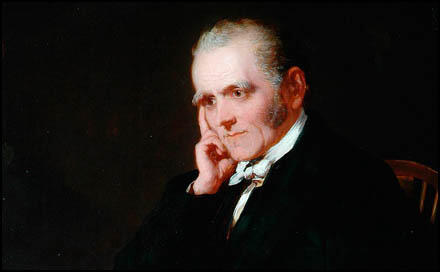

On this day in 1612 Thomas Fairfax, the son of Ferdinando Fairfax, was born in Denton, Yorkshire. A soldier, he served under Baron Vere in the Netherlands.

Fairfax was knighted by Charles I in 1641. However, when the Civil War broke out in 1642 he took the side of Parliament and played an important in the defeat of Royalist forces at Marston Moor in 1644.

In February 1645, Parliament decided to form a new army of professional soldiers. This army of 22,000 men became known as the New Model Army. Its commander-in-chief was General Fairfax, while Oliver Cromwell was put in charge of its cavalry.

Members of the New Model Army received proper military training and by the time they went into battle they were very well-disciplined. In the past, people became officers because they came from powerful and wealthy families. In the New Model Army men were promoted when they showed themselves to be good soldiers. For the first time it became possible for working-class men to become army officers.

The New Model Army took part in its first major battle just outside the village of Naseby in Northamptonshire on 14 June 1645. The battle began when Prince Rupert led a charge against the left wing of the parliamentary cavalry which scattered and Rupert's men then gave chase.

While this was going on Oliver Cromwell launched an attack on the left wing of the royalist cavalry. This was also successful and the royalists that survived the initial charge fled from the battlefield. While some of Cromwell's cavalry gave chase, the majority were ordered to attack the now unprotected flanks of the infantry. Charles I was waiting with 1,200 men in reserve. Instead of ordering them forward to help his infantry he decided to retreat. Without support from the cavalry, the royalist infantry realised their task was impossible and surrendered.

By the time Prince Rupert's cavalry returned to the battlefield the fighting had ended. Rupert's cavalry horses were exhausted after their long chase and were not in a fit state to take on Cromwell's cavalry. Rupert had no option but to ride off in search of Charles I.

The battle was a disaster for the king. About 1,000 of his men had been killed, while another 4,500 of his most experienced men had been taken prisoner. The Parliamentary forces were also able to capture Charles' baggage train that contained his complete stock of guns and ammunition.

Thomas Fairfax was politically a conservative and was opposed to the trial of Charles I in 1648. However, he willingly suppressed the Levellers in the army.

Fairfax was elected to the House of Commons (1654-1658) but did not attend proceedings. Fairfax supported the recall of the monarchy in 1660 but played no role in politics during the reign of Charles II. Thomas Fairfax died in 1671.

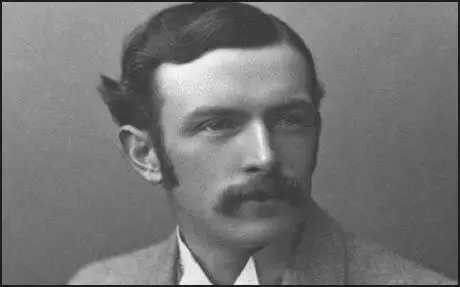

On this day in 1784 John Fielden, the third son of Joshua Fielden, was born in Todmorden. Joshua Fielden was the owner of a small textile business.

At the age of ten John was required to work in his family's cotton factory for ten hours a day. When he had served his apprenticeship his father made John and his four brothers, partners in Joshua Fielden & Sons. Once a week Joshua and his sons would take their cloth to Manchester, 20 miles away, and collect the bags of imported cotton. This journey became easier with the building of the Rochdale Canal in 1804.

Fielden pointed out: "In the counties of Derbyshire, Nottingham, and, more particularly, in Lancashire the newly-invented machinery was used in large factories built on the side of rivers capable of turning the water-wheel. Thousands of hands were suddenly required in these places, remote from towns. The small and nimble fingers of little children being by far the most in request."

When Joshua Fielden died in 1811, the business was still fairly small. Joshua left £200 in cash and the property and machinery was estimated to be worth £5000. Jointly run by John and his four brothers, Samuel, Joshua, James and Thomas, the business expanded rapidly over the next few years.

John married Ann Grindrod, the daughter of a Rochdale grocer in 1811. The couple had seven children: Jane (1814), Samuel (1816), Mary (1817), Ann (1819), John (1822), Joshua (1827) and Ellen (1829). John Fielden's wife died of a heart-attack in 1831 after seeing a child drown in the local canal.

Brought up as a Quaker, Fielden had been taught at an early age to be concerned about the welfare of the people the company employed. In 1816 the four brothers presented a petition to Parliament that argued for factory legislation to protect child workers. In 1822 Fielden was a founder member of the Todmorden Unitarian Society, a religious group active in the social reform movement. Two years later, Fielden funded the building of the Unitarian Chapel. Fielden also established and taught at the Unitarian School in the village.

When the wages of factory workers began to fall in the 1820s, Fielden started advocating the introduction of a minimum wage. Fielden argued that if workers were paid a decent wage, this would be good for the British economy as it was increase spending on manufactured goods. He also believed that low wages and long hours had a disastrous effect on the health of the workers. As an employer Fielden practised what he preached and paid good wages to his workers. In an attempt to improve wages Fielden gave support to John Doherty and his Grand Union of Operative Spinners. Fielden also worked with Doherty in the formation of the Society for the Protection of Children Employed in Cotton Factories.

Fielden explained in one speech: "At a meeting in Manchester a man claimed that a child in one mill walked twenty-four miles a day. I was surprised by this statement, therefore, when I went home, I went into my own factory, and with a clock beside me, I watched a child at her work, and having watched her for some time, I then calculated the distance she had to go in a day, and to my surprise, I found it to be nothing short of twenty miles."

By 1832 Fielden Brothers was one of the largest textile companies in Britain. The company owned 684 power looms and was responsible for about one per cent of the total cloth being produced in Yorkshire and Lancashire.

John Fielden believed that adult men should have the vote and was active in the Manchester Political Union. He established the Todmorden Political Union and in 1831 Fielden and William Cobbett were selected as Radical candidates for Oldham in the election that followed the passing of 1832 Reform Act. Cobbett and Fielden both won easily and became the leaders of the reform movement in the House of Commons.

After the death of William Cobbett in 1835, reformers relied heavily on John Fielden to put their case in the House of Commons. Campaigns supported by Fielden included the six demands of the Chartist movement and opposition to the 1834 Poor Law Act. Fielden also campaigned against the payment of compensation to slave owners and supported revision of the Corn Laws. Fielden was also in favour of a national system of education under public control and always voted against measures that attempted to give financial aid to church schools.

John Fielden main political activity concerned factory legislation. Although Fielden personally believed that a ten hour day was too long for children, he supported the campaign for a ten hour day as he was aware this was the only thing that Parliament would accept. It was a long hard struggle and it was not until 1847 that Parliament passed the Ten Hours Act. As Lord Ashley had been defeated in the General Election earlier that year, John Fielden had the task of taking the act through Parliament. Although Ashley had been the official leader of the factory reformers, no one had done more than Fielden to obtain this reform.

By the 1840s, John Fielden's son, Samuel Fielden, became the dominant figure in the Fielden Brothers company. In 1845 Fielden purchased a small country estate, Skeynes, near Edenbridge in Kent. John Fielden died at Skeynes on 29th May, 1849. He is buried in a simple grave at the Unitarian Chapel in Todmorden.

On this day in 1829 Catherine Booth was born. Catherine Mumford, the daughter of a coachbuilder, was born in Ashbourne, Derbyshire, on 17th January 1829. When she was a child the family moved to Boston, Lincolnshire and later they lived in Brixton, London. Catherine was a devout Christian and by the age of twelve she had read the Bible eight times. She had a social conscience from an early age. On one occasion she protested to the local policeman that he had been too rough on a drunken man he had arrested and frog-marched to the local lock-up.

Catherine did not enjoy good health. At the age of fourteen she developed spinal curvature and four years later, incipient tuberculosis. It was while she was ill in bed that she began writing articles for magazines warning of the dangers of drinking alcohol. Catherine was a member of the local Band of Hope and a supporter of the national Temperance Society.

In 1852 Catherine met William Booth, a Methodist minister. William had strong views on the role of church ministers believing they should be "loosing the chains of injustice, freeing the captive and oppressed, sharing food and home, clothing the naked, and carrying out family responsibilities." Catherine shared William's commitment to social reform but disagreed with his views on women. Catherine was an avowed feminist. On one occasion she objected to William describing women as the "weaker sex". William was also opposed to the idea of women preachers. When Catherine argued with William about this he added that although he would not stop Catherine from preaching he would "not like it". Despite their disagreements about the role of women in the church, the couple married on 16th June 1855, at Stockwell New Chapel.

It was not until 1860 that Catherine Booth first started to preach. One day in Gateshead Bethesda Chapel, a strange compulsion seized her and she felt she must rise and speak. Later she recalled how an inner voice taunted her: "You will look like a fool and have nothing to say". Catherine decided that this was the Devil's voice: "That's just the point," she retorted, "I have never yet been willing to be a fool for Christ. Now I will be one."

Catherine's sermon was so impressive that William changed his mind about women's preachers. Catherine Booth soon developed a reputation as an outstanding speaker but many Christians were outraged by the idea. As Catherine pointed out at that time it was believed that a woman's place was in the home and "any respectable woman who raised her voice in public risked grave censure."

In 1864 the couple began in London's East End the Christian Mission which later developed into the Salvation Army. Catherine Booth took a leading role in these revival services and could often be seen preaching in the dockland parishes of Rotherhithe and Bermondsey. Though often imprisoned for preaching in the open air, members of the Salvation Army fought on, waging war on poverty and injustice.

The Church of England were at first extremely hostile to the Salvation Army. Lord Shaftesbury, a leading politician and evangelist, described William Booth as the "anti-christ". One of the main complaints against Booth was his "elevation of women to man's status". In the Salvation Army a woman officer enjoyed equal rights with a man. Although Booth had initially rejected the idea of women preachers, he had now completely changed his mind and wrote that "the best men in my Army are the women."

Catherine Booth began to organize what became known as Food-for-the-Million Shops where the poor could buy hot soup and a three-course dinner for sixpence. On special occasions such as Christmas Day, she would cook over 300 dinners to be distributed to the poor of London.

By 1882 a survey of London discovered that on one weeknight, there were almost 17,000 worshipping with the Salvation Army, compared to 11,000 in ordinary churches. Even, Dr. William Thornton, the Archbishop of York, had to accept that the Salvation Army was reaching people that the Church of England had failed to have any impact on.

It was while working with the poor in London that Catherine found out about what was known as "sweated labour". That is, women and children working long hours for low wages in very poor conditions. In the tenements of London, Catherine discovered red-eyed women hemming and stitching for eleven hours a day. These women were only paid 9d. a day, whereas men doing the same work in a factory were receiving over 3s. 6d. Catherine and fellow members of the Salvation Army attempted to shame employers into paying better wages. They also attempted to improve the working conditions of these women.

Catherine was particularly concerned about women making matches. Not only were these women only earning 1s. 4d. for a sixteen hour day, they were also risking their health when they dipped their match-heads in the yellow phosphorus supplied by manufacturers such as Bryant & May. A large number of these women suffered from 'Phossy Jaw' (necrosis of the bone) caused by the toxic fumes of the yellow phosphorus. The whole side of the face turned green and then black, discharging foul-smelling pus and finally death.

Women like Catherine Booth and Annie Beasant led a campaign against the use of yellow phosphorus. They pointed out that most other European countries produced matches tipped with harmless red phosphorus. Bryant & May responded that these matches were more expensive and that people would be unwilling to pay these higher prices.

Catherine Booth died of cancer on 4th October 1890. The campaigns that were started by Catherine were not abandoned. William Booth decided he would force companies to abandon the use of yellow phosphorus. In 1891 the Salvation Army opened its own match-factory in Old Ford, East London. Only using harmless red phosphorus, the workers were soon producing six million boxes a year. Whereas Bryant & May paid their workers just over twopence a gross, the Salvation Army paid their employees twice this amount.

William Booth organised conducted tours of MPs and journalists round this 'model' factory. He also took them to the homes of those "sweated workers" who were working eleven and twelve hours a day producing matches for companies like Bryant & May. The bad publicity that the company received forced the company to reconsider its actions. In 1901, Gilbert Bartholomew, managing director of Bryant & May, announced it had stopped used yellow phosphorus.

Catherine Booth and William Booth had eight children, all of whom were active in the Salvation Army. William Bramwell Booth (1856-1929) was chief of staff from 1880 and succeeded his father as general in 1912. Catherine's second son, Ballington Booth (1857-1940), was commander of the army in Australia (1883-1885) and the USA (1887-1896). One of her daughters, Evangeline Cory Booth (1865-1950) was elected General of the Salvation Army in 1934.

On this day in 1863 David Lloyd George, the second child and the elder son of William George and Elizabeth Lloyd, was born in Chorlton-on-Medlock.

Lloyd George's father was the son of a farmer who had a desire to become a doctor or a lawyer. However, unable to afford the training, William George became a teacher. He wrote in his diary, "I cannot make up my mind to be a school master for life... I want to occupy higher ground somehow or other."

William George married Elizabeth Lloyd, the daughter of a shoemaker, on 16th November 1859. He became a school teacher in Newchurch in Lancashire, but in 1863, he bought the lease of Bwlford, a smallholding of thirty acres near Haverfordwest. However, he died, from pneumonia aged forty-four, on 7th June, 1864.

Elizabeth Lloyd, was only 36 years-old and as well as having two young children, Mary Ellen and David, she was also pregnant with a third child. Elizabeth sent a telegram to her unmarried brother, Richard Lloyd, who was a master-craftsman with a shoe workshop in Llanystumdwy, Caernarvonshire. He arranged for the family to live with him. According to Hugh Purcell: "Richard Lloyd... was an aoto-didact whose light burned long into the night as he sought self-improvement. He ran the local debating society and regarded politics as a public service to improve people's lives."

The Lloyd family were staunch Nonconformists and worshipped at the Disciples of Christ Chapel in Criccieth. Richard Lloyd was Welsh-speaking and deeply resented English dominance over Wales. Richard was impressed by David's intelligence and encouraged him in everything he did. David's younger brother, William George, later recalled: "He (David) was the apple of Uncle Lloyd's eye, the king of the castle and, like the other king, could do no wrong... Whether this unrestrained admiration was wholly good for the lad upon whom it was lavished, and indeed for the man who evolved out of him, is a matter upon which opinions may differ."

David Lloyd George acknowledged the help given to him by Richard Lloyd: "All that is best in life's struggle I owe to him first... I should not have succeeded even so far as I have were it not for the devotion and shrewdness with which he has without a day's flagging kept me up to the mark... How many times have I done things... entirely because I saw from his letters that he expected me to do them."

Lloyd George was an intelligent boy and did very well at his local school. Lloyd George's headmaster, David Evans, was described as a "teacher superlative quality". His "outstanding gift was for holding the attention of the young and for arousing their enthusiasm". Lloyd George said that "no pupil ever had a finer teacher". Evans returned the compliment: "no teacher ever had a more apt pupil".

In 1877 Lloyd George decided he wanted to be a lawyer. After passing his Law Preliminary Examination he found a post at a firm of solicitors in Portmadog. He started work soon after his sixteenth birthday. He passed his final law examination in 1884 with a third-class honours and established his own law practice in Criccieth. He soon developed a reputation as a solicitor who was willing to defend people against those in authority.

Lloyd George began getting involved in politics. His uncle was a member of the Liberal Party with a strong hatred of the Conservative Party. At the age of 18 he visited the House of Commons and noted in his diary: "I will not say that I eyed the assembly in a spirit similar to that in which William the Conqueror eyed England on his visit to Edward the Confessor, as the region of his future domain."

In 1888 Lloyd George married Margaret Owen , the daughter of a prosperous farmer. He developed a "deserved reputation for promiscuity". One of his biographers has pointed out: "Not for nothing was his nickname the Goat. He had a high sex drive without the furtiveness that often goes with it. Although he knew that the fast life, as he called it, could ruin his career he took extraordinary risks. Only two years after his marriage he had an affair with an attractive widow of Caernavon, Mrs Jones... She gave birth to a son who grew up to look remarkably like Richard, Lloyd George's legitimate son who was born the previous year."

Lloyd George joined the local Liberal Party and became an alderman on the Caernarvon County Council. He also took part in several political campaigns including one that attempted to bring an end to church tithes. Lloyd George was also a strong supporter of land reform. As a young man he had read books by Thomas Spence, John Stuart Mill and Henry George on the need to tackle this issue. He had also been impressed by pamphlets written by George Bernard Shaw and Sidney Webb of the Fabian Society on the need to tackle the issue of land ownership.

In 1890 David Lloyd George, was selected as the Liberal candidate for the Caernarvon Borough constituency. A by-election took place later that year when the sitting Conservative MP died. Lloyd George fought the election on a programme which called for religious equality in Wales, land reform, the local veto in granting licenses for the sale of alcohol, graduated taxation and free trade. Lloyd George won the seat by 18 votes and at twenty-seven became the youngest member of the House of Commons.

On this day in 1872 the first meeting of the Central Society for Women's Suffrage. In November 1871, Jacob Bright suggested at the annual general meeting of the Manchester Society for Women's Suffrage that greater pressure could be applied on members of the House of Commons by establishing a Central Committee for Women's Suffrage in London. The first meeting of this new group was held on 17th January 1872. The first executive committee included Frances Power Cobbe, Priscilla Bright McLaren, Agnes Garrett and Lilias Ashworth Hallett.

In 1874 the Central Committee introduced a yearly subscription fee of one shilling. This enabled free admission to all meetings. New members in that year included Millicent Fawcett, Florence Nightingale and Harriet Martineau. In 1881 Lydia Becker became secretary of the Central Committee for Women's Suffrage. Other members of the executive committee included Helen Blackburn, Jessie Boucherett, Frances Power Cobbe, Millicent Fawcett, Eva Maclaren, Priscilla Bright McLaren and Helen Taylor.

On this day in 1908 Edith New is arrested after chaining herself to the railings of 10 Downing Street. According to The Daily Express: "Each suffragist wore round her waist a long, steel chain - not unlike a very heavy dog chain. Each took the loosened end of the chain, threw it round the railings, and fixed it to the rest of the chain. This was done so deftly that it was not until the police heard the click of the lock that they understood the clever move by which the suffragists had outwitted them, and prevented for a time their own removal. Votes for women! shouted the two voluntary prisoners simultaneously. Votes for Women!"

On this day in 1914 John Edward Simkin was born in Finsbury, London. His father, John Edward Simkin, was killed during the First World War. His mother Jane Simkin, remarried Harry White.

In 1935, Jane and Harry, John, his brother William, and their half-sister, Lily White, moved to a flat in Garnham Street, Stoke Newington. Muriel Hughes, was asked by her uncle to help the family with their radio aerial.

Both of Mrs White's sons showed an interest in twenty-year-old Muriel. Bill wanted to ask her out, but John (known to all of his friends as Ted) told his mother, that he had just met "the girl he was going to marry". Bill was the first one to make a move, but it was Ted who successfully invited her to go out with him to see the film Mutiny on the Bounty, starring Charles Laughton and Clark Gable.

Muriel's sister, Stella Hughes, was only nine-years-old when Ted took Muriel on their first date. Stella was anxious to see the new boyfriend and when he brought her back home she leant over the upstairs bannister rails. However, she could not see him as he was standing outside, but she could hear him singing a song to Muriel, Without a Word of Warning, a hit for Bing Crosby that first appeared in the film, Two for Tonight (1935).

Ted Simkin worked at the large Mac Fisheries depot at Finsbury Park in North London and spent time as a porter at the famous Billingsgate Fish Market before becoming a "fish salesman". Muriel talked fondly about the high-quality fish he was able to supply free of charge to the Hughes family. According to Muriel, during this period, Ted had a very outgoing personality, and with his accordion playing, he was a popular guest at parties.

Stella says that Ted was always telling jokes and was a very funny man. He was also a fanatical Spurs supporter and he often took her to White Hart Lane to see games. Muriel was not interested in football and did not go to games. Stella admitted she was not interested either but she took the opportunity to go out with Ted. However, she soon learnt to love the game and has been a life-long supporter of Spurs.

Ted had not known his father, John Edward Simkin, who had been killed on the Western Front in 1915 when he was only one year-old. He did not see much of his stepfather, Harry White, who left the family home when he was very young, According to Muriel it seems that an older colleague at work, Izzie Wright, became a father figure. In the early days of their relationship they went on outings to the countryside or the seaside with other couples, including Izzie and his wife Lilly, and Muriel's cousin Winnie Treweek and her new husband George Logsdon.

John Simkin married Muriel Hughes at West Hackney Church, Stoke Newington on 26th August 1939. They went away for two weeks at Weymouth. While on their honeymoon Neville Chamberlain announced that Britain was at war with Germany. She recalled: "We were on our honeymoon when war was declared. We had planned to have a fortnight's holiday, but we had to come home after a week. It was not a very good start to our married life."

On their return they moved into their new council house in 98 Rogers Road, Dagenham, Essex. At the time of her marriage, Muriel was employed as an "Examiner and Finisher" at the London tailoring firm of Horne Brothers, earning 8s 6d a week. On the first day of the Second World War, Parliament passed the National Service (Armed Forces) Act, under which all men between 18 and 41 were made liable for conscription. The registration of all men in each age group in turn began on 21st October for those aged 20 to 23. Ted continued his work as a salesman at the fish market until he was conscripted into the Royal Artillery on 15th July 1940.

"I went with my parents to London to see off my husband and brother. They had both been called up by the army. After we left them at the railway station we got caught in an air-raid. We had to get off the bus after it caught fire. We ran for shelter. While we were running, I looked at my dad and he appeared to be on fire. I said: "Dad, you're alight." He nearly had a heart attack and I was not very popular when he discovered that I was mistaken and that it was only the torch in his pocket that had been accidentally turned on while he was running."

Young women without children were encouraged to do war work. Muriel joined the Briggs munitions factory in Dagenham. During the Blitz, these factories were a major target for the Luftwaffe. Mum's work was highly dangerous: "It was a terrible job, but we had no option. We all had to do war work... We had to wait until the second alarm before we were allowed to go to the shelter. The first bell was a warning they were coming. The second was when they were overhead. They did not want any time wasted. The planes might have gone straight past and the factory would have stopped for nothing."

These regulations made the work especially precarious. "Sometimes the Germans would drop their bombs before the second bell went. On one occasion a bomb hit the factory before we were given permission to go to the shelter. The paint department went up. I saw several people flying through the air and I just ran home. I was suffering from shock. I was suspended for six weeks without pay. They would have been saved if they had been allowed to go after the first alarm... We were risking our lives in the same way as the soldiers were."

On the outbreak of the war, Sir John Anderson, the Home Secretary and the Minister of Home Security, commissioned the engineer, William Patterson, to design a small and cheap shelter that could be erected in people's gardens. Within a few months nearly one and a half million of these Anderson Shelters were distributed to people living in areas expected to be bombed by the Luftwaffe. Anderson shelters were given free to poor people. Men who earned more than £5 a week could buy one for £7. The main problem was that under a quarter of the public had no gardens. Made from six curved sheets bolted together at the top, with steel plates at either end, and measuring 6ft 6in by 4ft 6in (1.95m by 1.35m) the shelter could accommodate six people. These shelters were half buried in the ground with earth heaped on top. The entrance was protected by a steel shield and an earthen blast wall.

Muriel had one of these shelters in her garden. "We had an Anderson shelter in the garden. You were supposed to go into the shelter every night. I used to take my knitting. I used to knit all night. I was too frightened to go to sleep. You got into the habit of not sleeping. I've never slept properly since. It was just a bunk bed. I did not bother to get undressed. It was cold and damp in the shelter. I was all on my own because my husband was in the army."

In 1940 Muriel and Ted had a lucky escape: "You would go nights and nights, and nothing happened. On one occasion when my husband was on leave, I think it was a weekend, we decided we would spend the night in bed instead of in the shelter. I heard the noise and woke up and I would see the sky. They had dropped a basket of incendiary bombs and we had got the lot. Luckily not one went off. Next morning the bombs were standing up in the garden as if they had grown in the night."

Muriel claimed that certain things improved during the war: "People on the whole were more friendly during the war than they are today - happier even. People helped you out. You had to have a sense of humour. You couldn't get through it without that. The worst part was having you husband and brothers away from you. We never heard from Jack, my brother, for five months. He couldn't communicate at all because he was involved in important battles in North Africa. It was very worrying. We knew a lot of his regiment had been killed. Then we saw his picture in the Daily Express newspaper. He was being inspected by General Montgomery. It was not until then that we knew he was alive."

Muriel Simkin managed to survive the bombing raids, but the extended family did suffer one major tragedy. "Rosie, my mum's sister, had to go to hospital to have a baby. Her mother-in-law looked after her three-year-old son. There was a bombing raid and Rosie's son and mother-in-law rushed to Bethnal Green underground station. Going down the stairs somebody fell. People panicked and Rosie's son was trampled to death."

John Edward Simkin was called up for military service on 15 July 1940 and joined the Royal Artillery. He was a member of a team operating an anti-aircraft battery during the Battle of Britain. Later he served at Biggin Hill, Rochford and Dover. He was wounded in 1944 and as a result missed taking part in the D-Day landings.

After the Second World War he worked at the Every-Ready factory in Edmonton. John Simkin died in road accident on 16th October, 1956.

On this day in 1915 Lucy Parsons led a march against hunger and unemployment in Chicago. Lucy Waller, the daughter of John Waller, a Muscogee, and Marie del Gather from Mexico, was born in Texas in 1851. Her parents died when she was a child and was raised by relatives.

In 1870 she met Albert Parsons, a former soldier in the Confederate Army but now a Radical Republican. They married the following year but mixed relationships were unacceptable and so the couple moved to Chicago. Parsons became a printer but after becoming involved in trade union activities he was blacklisted.

Lucy had several articles published in radical journals such as 'The Socialist' and 'The Alarm'. She was also a member of the Socialist Labor Party and the International Working Men's Association (the First International), a labor organization that supported racial and sexual equality.

Albert Parsons was arrested and charged with the Haymarket Bombing. Although no evidence was provided in court that linked Parsons to the crime, he was found guilty along with August Spies, Adolph Fisher, Louis Lingg and George Engel and was sentenced to death. He was executed on 11th November, 1887.

Parsons continued to be politically active after the death of her husband. A founding member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) she published the radical journals, Freedom and The Liberator where she campaigned for trade union rights and an end to lynching.

Lucy Parsons was also a member of the National Committee of the International Labor Defense, an organisation that helped African Americans unjustly accused of crimes such as the Scottsboro Nine. In 1939 Parsons joined the American Communist Party. Lucy Parsons died in a fire in her Chicago home on 7th March 1942.

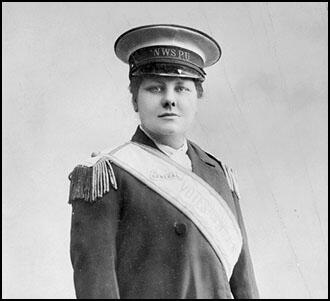

On this day in 1949 women's suffrage leader Flora Drummond died.

Flora Gibson was born in Manchester on 4th August 1879, but spent her childhood on the Isle of Arran. She took a business training course in Glasgow and also attended lectures on economics at the University of Glasgow. Flora qualified as a post mistress but was refused entry because she was too short.

After her marriage to Joseph Drummond in 1898 Flora lived in Manchester and she and her husband joined the Independent Labour Party. She was also a member of the Fabian Society and the Clarion Club. Her husband worked as an upholsterer. At the time she was employed in a baby-linen factory.

According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999): "Flora Drummond... later explained her involvement in the women's suffrage movement by her experience at this time. She saw that women were paid such low wages that they were forced to engage in prostitution in order to live. Flora Drummond's husband, an upholsterer, was often out of work and it seems unlikely that she would have elected to take low-paid work if she could have been more gainfully employed."

Flora Drummond became a member of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) and in the summer of 1905 she joined Hannah Mitchell in the campaign to recruit women to the cause in Lancashire towns. On 13th October she was with Teresa Billington-Greig at the Free Trade Hall when they witnessed the arrests of Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney. Pankhurst and Kenney were found guilty of assault and fined five shillings each.

In 1906 Drummond joined Annie Kenney, Mary Gawthorpe, Nellie Martel, Helen Fraser, Adela Pankhurst and Minnie Baldock as WSPU full-time organizers. As Christabel Pankhurst pointed out: "Clement's Inn, our headquarters, was a hive seething with activity... General Flora Drummond's office was full of movement. As department was added to department, Clement's Inn seemed always to have one more room to offer. Mary Richardson described her as having a "broad, lovable Scottish accent."

On 9th March, 1906, Flora Drummond and Annie Kenney, led a demonstration to Downing Street, repeatedly knocking on the door of the Prime Minister, Henry Campbell-Bannerman. Drummond and Kenney were arrested but Campbell-Bannerman refused to press charges and they were released. A few months later Drummond was arrested outside the House of Commons and she served her first term of imprisonment in Holloway Prison.

In 1908 Flora Drummond was put in charge of the WSPU offices at Clement's Inn. It was during this time that she acquired the nickname "General". Emmeline Pankhurst said that "Mrs. Drummond is a woman of very great public spirit; she is an admirable wife and mother; she has very great business ability, and she has maintained herself, although a married woman, for many years, and has acquired for herself the admiration and respect of all the people with whom she has had business relations."

The WSPU organised a mass meeting to take place on 21 June 1908 called Women's Sunday at Hyde Park. The leadership intended it "would out-rival any of the great franchise demonstrations held by the men" in the 19th century. Sunday was chosen so that as many working women as possible could attend. It is claimed that it attracted a crowd of over 300,000. At the time, it was the largest protest to ever have taken place in Britain. Speakers included Gladice Keevil, Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst, Adela Pankhurst, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Mary Gawthorpe, Jennie Baines, Rachel Barrett, Marie Brackenbury, Georgina Brackenbury, Annie Kenney, Nellie Martel, Marie Naylor, Flora Drummond and Edith New.

Flora Drummond was arrested with Christabel Pankhurst in October 1908 and charged with the incitement to "rush the House of Commons". She was sentenced to three months' imprisonment but she was discharged after nine days, when the prison authorities discovered that she was pregnant. Her son was named "Keir" after Keir Hardie.

In 1909 Drummond moved to Glasgow. She wrote to Minnie Baldock that her husband, Joseph Drummond, had decided to go and live in Australia. She organized the WSPU campaign in the January 1910 General Election. In 1911 she returned to Clement's Inn where she was put in charge of all the WSPU branches in the country on a wage of £3 10s a week.

Drummond was arrested during a demonstration on 15th April 1913. In court she argued that if she was imprisoned she would go on hunger-strike. The Daily Herald reported: "She (Flora Drummond) did not like the idea of hunger striking any more than the most normal human beings, but hunger strike she would if she were sent to gaol." The court decided to withdraw the charges against her.

In May 1914, she was arrested again. For the ninth time she was imprisoned. After going on hunger strike she was released under the Cat and Mouse Act. Drummond recuperated in the Isle of Arran but she returned to Clement's Inn after the outbreak of the First World War. The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort.

Emmeline Pankhurst announced that all militants had to "fight for their country as they fought for the vote." Ethel Smyth pointed out in her autobiography, Female Pipings for Eden (1933): "Mrs Pankhurst declared that it was now a question of Votes for Women, but of having any country left to vote in. The Suffrage ship was put out of commission for the duration of the war, and the militants began to tackle the common task."

During the First World War Drummond toured the country in an attempt to persuade trade unionists from going on strike. In 1917 Drummond joined with Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst to form the The Women's Party. Its twelve-point programme included: (1) A fight to the finish with Germany. (2) More vigorous war measures to include drastic food rationing, more communal kitchens to reduce waste, and the closing down of nonessential industries to release labour for work on the land and in the factories. (3) A clean sweep of all officials of enemy blood or connections from Government departments. Stringent peace terms to include the dismemberment of the Hapsburg Empire." The WP also supported: "equal pay for equal work, equal marriage and divorce laws, the same rights over children for both parents, equality of rights and opportunities in public service, and a system of maternity benefits." Christabel and Emmeline had now completely abandoned their earlier socialist beliefs and advocated policies such as the abolition of the trade unions.

After the passing of the Qualification of Women Act in 1918, Flora Drummond helped Christabel Pankhurst, who represented the The Women's Party in Smethwick. Despite the fact that the Conservative Party candidate agreed to stand down, Christabel lost a straight fight with the representative of the Labour Party by 775 votes.

In 1922 Flora divorced Joseph Drummond and two years later married Alan Simpson, an engineer from Glasgow. Drummond had now completely rejected her early socialism and now held right-wing opinions and along with Elsie Bowerman and Norah Dacre Fox established the Women's Guild of Empire, a right wing league opposed to communism. Her biographer, Krista Cowman, pointed out: "When the war ended she was one of the few former suffragettes who attempted to continue the popular, jingoistic campaigning which the WSPU had followed from 1914 to 1918. With Elsie Bowerman, another former suffragette, she founded the Women's Guild of Empire, an organization aimed at furthering a sense of patriotism in working-class women and defeating such socialist manifestations as strikes and lock-outs." By 1925 Drummond claimed the organization had a membership of 40,000. In April 1926, she led a demonstration that demanded an end to the industrial unrest that was about to culminate in the General Strike.

Juanita Frances, who worked with Drummond in the Women's Guild of Empire, described her as someone who "looked as she spoke" and was "like a charwoman" and that she was "rather shabby" and "a little unkempt".

Flora Drummond became involved in a dispute with Norah Dacre Fox who had criticised the violent methods of the British Union of Fascists. On 22nd February 1935 Norah argued in The Blackshirt that Drummond had once "defied all law and order; smashed not only windows, but all the meetings of Cabinet Ministers on which she could lay hands, and was for long the daily terror of the Public Prosecutor and the despair of Bow Street!" Norah described Drummond and other former suffragettes as "extinct volcanoes either wandering about in the backwoods of international pacifism and decadence, or prostrating themselves before the various political parties."

On this day in 2004 Elisabeth Scholl was interviewed by the Daily Mirror on the White Rose group. During the Second World War a group of medical students at the University of Munich got together to discuss poetry. This included Hans Scholl, her brother, Alexander Schmorell, Jürgen Wittenstein, Christoph Probst and Willi Graf. At meetings they took it in turns reading poems and the others had to guess the name of the poet. One evening, on 21st May, 1942, Hans read a poem about a tyrant that contained the passage: "Mounting the rubbish heap around him/He spews his message on the world." The people living under this tyrant accepted his rule: "The masses lived in utter shame/For foulest deeds they felt no blame." At the end, the poem predicts that this nightmare period will pass with the overthrow of the tyrant, and one day his reign will be looked back upon, and talked about, like the Black Plague.

No one at the meeting could identify the poet. Probst suggested that it had been written in Germany recently. "Anyway, those verses couldn't be more timely. They might have been written yesterday." Schmorell agreed and suggested that the poem should be mimeographed and dropped over Germany from an airplane "with a dedication to Adolf Hitler". Graf added that it should be printed in the Völkischer Beobachter. Scholl then told the group the name of the poet was Gottfried Keller. "Actually, the verses were written in 1878, and they don't refer to events in Germany at all, but to a political situation in Switzerland. The author is Gottfried Keller".

After this the meetings tended to be more political and the members discussed ways they could show their disapproval of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party. However, it remained a discussion group. As Anton Gill, the author of An Honourable Defeat: A History of German Resistance to Hitler (1994) has pointed out: "The group had no wish to throw bombs, or to cause any injury to human life. They wanted to influence people's minds against Nazism and militarism."

The friends became known as the White Rose group. Hans Scholl soon emerged as the group's leader: "The role was tacitly bestowed on him by virtue of that quality in his personality that, in any group, made him the focus of attention. Alex Schmorell was usually at his side, his close collaborator. Between them, they arranged for meetings and meeting places.... Sometimes they met in Hans' room for impromptu talk and discussion. For larger meetings, they gathered at the Eickemeyer studio or the villa of Dr. Schmorell, an indulgent father who shared many of his son's views."

Christoph Probst was promoted to the rank of sergeant in the medical service and posted to Innsbruck. (7) Over the next few weeks Sophie Scholl, Traute Lafrenz, Lilo Ramdohr and Gisela Schertling became active members. Inge Scholl, Hans and Sophie's sister, who lived in Ulm, also attended meetings whenever she was in Munich. "There was no set criterion for entry into the group that crystallized around Hans and Sophie Scholl... It was not an organization with rules and a membership list. Yet the group had a distinct identity, a definite personality, and it adhered to standards no less rigid for being undefined and unspoken. These standards involved intelligence, character, and especially political attitude."

The group of friends had discovered a professor at the university who shared their dislike of the Nazi regime. Kurt Huber was Sophie's philosophy teacher. However, medical students also attended his lectures, which "were always packed, because he managed to introduce veiled criticism of the regime into them". The 49 year-old professor, also joined in private discussions with what became known as the White Rose group. Hans told his sister, Inge Scholl, "though his hair was turning grey, he was one of them".

According to Elisabeth Scholl, the White Rose group was formed because of the execution of members of the resistance: "We learned in the spring of 1942 of the arrest and execution of 10 or 12 Communists. And my brother said, In the name of civic and Christian courage something must be done. Sophie knew the risks. Fritz Hartnagel told me about a conversation in May 1942. Sophie asked him for a thousand marks but didn’t want to tell him why. He warned her that resistance could cost both her head and her neck. She told him, I’m aware of that. Sophie wanted the money to buy a printing press to publish the anti-Nazi leaflets.”

In June 1942 the White Rose group began producing leaflets. They were typed single-spaced on both sides of a sheet of paper, duplicated, folded into envelopes with neatly typed names and addresses, and mailed as printed matter to people all over Munich. At least a couple of hundred were handed into the Gestapo. It soon became clear that most of the leaflets were received by academics, civil servants, restaurateurs and publicans. A small number were scattered around the University of Munich campus. As a result the authorities immediately suspected that students had produced the leaflets.

The opening paragraph of the first leaflet said: "Nothing is so unworthy of a civilized nation as allowing itself to be "governed" without opposition by an irresponsible clique that has yielded to base instinct. It is certain that today every honest German is ashamed of his government. Who among us has any conception of the dimensions of shame that will befall us and our children when one day the veil has fallen from our eyes and the most horrible of crimes - crimes that infinitely outdistance every human measure-reach the light of day? If the German people are already so corrupted and spiritually crushed that they do not raise a hand, frivolously trusting in a questionable faith in lawful order in history; if they surrender man's highest principle, that which raises him above all other God's creatures, his free will; if they abandon the will to take decisive action and turn the wheel of history and thus subject it to their own rational decision; if they are so devoid of all individuality, have already gone so far along the road toward turning into a spiritless and cowardly mass - then, yes, they deserve their downfall."

According to the historian of the resistance, Joachim Fest, this was a new development in the struggle against Adolf Hitler. "A small group of Munich students were the only protesters who managed to break out of the vicious circle of tactical considerations and other inhibitions. They spoke out vehemently, not only against the regime but also against the moral indolence and numbness of the German people." Peter Hoffmann, the author of The History of German Resistance (1977) claimed they must have been aware that they could do any significant damage to the regime but they "were prepared to sacrifice themselves" in order to register their disapproval of the Nazi government.

The second leaflet was published in the third week of June 1942 dealt with the treatment of Jews in Nazi Germany and in Eastern Europe. "Since the conquest of Poland three hundred thousand Jews have been murdered in this country in the most bestial way. Here we see the most frightful crime against human dignity, a crime that is unparalleled in the whole of history. For Jews, too, are human beings - no matter what position we take with respect to the Jewish question - and a crime of this dimension has been perpetrated against human beings. Someone may say that the Jews deserved their fate. This assertion would be a monstrous impertinence; but let us assume that someone said this - what position has he then taken toward the fact that the entire Polish aristocratic youth is being annihilated? (May God grant that this program has not fully achieved its aim as yet!) All male offspring of the houses of the nobility between the ages of fifteen and twenty were transported to concentration camps in Germany and sentenced to forced labor, and all girls of this age group were sent to Norway, into the bordellos of the SS!"

The leaflet then raised questions about the way the German population were responding to these atrocities: "Why tell you these things, since you are fully aware of them - or if not of these, then of other equally grave crimes committed by this frightful sub-humanity? Because here we touch on a problem which involves us deeply and forces us all to take thought. Why do the German people behave so apathetically in the face of all these abominable crimes, crimes so unworthy of the human race? Hardly anyone thinks about that. It is accepted as fact and put out of mind. The German people slumber on in their dull, stupid sleep and encourage these fascist criminals; they give them the opportunity to carry on their depredations; and of course they do so. Is this a sign that the Germans are brutalized in their simplest human feelings, that no chord within them cries out at the sight of such deeds, that they have sunk into a fatal consciencelessness from which they will never, never awake? It seems to be so, and will certainly be so, if the German does not at last start up out of his stupor, if he does not protest wherever and whenever he can against this clique of criminals, if he shows no sympathy for these hundreds of thousands of victims. He must evidence not only sympathy; no, much more: a sense of complicity in guilt. For through his apathetic behavior he gives these evil men the opportunity to act as they do; he tolerates this government which has taken upon itself such an infinitely great burden of guilt; indeed, he himself is to blame for the fact that it came about at all! "

The third leaflet claimed that the goal of the White Rose was to bring down the Nazi government. It suggested the strategy of passive resistance that was being used by students fighting against racial discrimination in the United States: "We want to try and show them that everyone is in a position to contribute to the overthrow of the system. It can be done only by the cooperation of many convinced, energetic people - people who are agreed as to the means they must use. We have no great number of choices as to the means. The only one available is passive resistance. The meaning and goal of passive resistance is to topple National Socialism, and in this struggle we must not recoil from our course, any action, whatever its nature. A victory of fascist Germany in this war would have immeasurable, frightful consequences. The first concern of every German is not the military victory over Bolshevism, but the defeat of National Socialism."

This leaflet was sent to Sophie Scholl's philosophy teacher, Kurt Huber. He was then invited to the home of Alexander Schmorell. He turned up but was reluctant to get involved in a discussion about resisting the Nazi government. Traute Lafrenz abruptly turned to Huber and asked if he had received a White Rose leaflet. "He must have paused; the question, so pointed and direct, from a young woman he had never met before, must have startled him. He undoubtedly was put on guard: Kurt Huber was a man who did not find independent, sophisticated, and intellectual women sympathetic. He was comfortable with women who accepted the role that nature had given them: the comforter, the nurturer, the provider of sanctuary for the struggling man in a hostile world. As he saw it, women were there to pour coffee for the men as they talked over the serious issues of the world; women were not there for intellectual companionship or friendship, but for spiritual succor. He replied to the young woman that yes, he had received a leaflet. He didn't say much beyond that, except that he doubted the impact of the leaflet was worth the terrible risks."

Yvonne Sherratt has pointed out that in contrast to Hitler's ideological opponents, "Huber was neither left-leaning nor Jewish. He was a nationalist conservative, believing in the sanctity of tradition and the importance of the nation." (15) Kurt Huber was also strongly anti-communist and was unhappy with the passage in the leaflet that said: "The first concern of every German is not the military victory over Bolshevism, but the defeat of National Socialism." Huber left the meeting without making it clear if he was willing to join the group.

The group needed funds for the printing and mailing of the leaflets. Fritz Hartnagel who was on leave, gave Sophie 1,000 Reichsmarks, for what she told him was "a good purpose". Falk Harnack, a member of the Red Orchestra resistance group, also provided help. As well as sending the leaflets in the mail, members of the group carried them in suitcases to towns in southern Germany and delivering them to their supporters. This was highly dangerous as the Gestapo often carried out searches of passengers in trains. As a result of this activity, resistance groups were set up in Hamburg and Berlin.

There is a photograph of Sophie Scholl that was taken on 23rd July, 1942 (see below). Richard F. Hanser, the author of A Noble Treason: The Story of Sophie Scholl (1979) has pointed out: "They are all standing next to an openwork iron fence whose top reaches only a few inches over their heads. Peering down at them over the fence is Sophie, who is standing on something on the other side. She has evidently been there for some time. Her satchel-like briefcase, probably filled with books, is hooked by its handles to one of the fence spikes. She is wearing a knitted sweater with broad stitches, and her dark hair is falling loosely to her shoulders.... In one of the photographs, her lifted arms are flung wide, and there is a correspondingly wide smile on her face. It is a light and girlish gesture at a time that could not have been happy for her."

A fourth leaflet was published in July 1942. It included detailed of the large number of German soldiers killed during Operation Barbarossa: "Neither Hitler nor Goebbels can have counted the dead. In Russia thousands are lost daily. It is the time of the harvest, and the reaper cuts into the ripe grain with wide strokes. Mourning takes up her abode in the country cottages, and there is no one to dry the tears of the mothers. Yet Hitler feeds with lies those people whose most precious belongings he has stolen and whom he has driven to a meaningless death." The ended the leaflet with the words: "We will not be silent. We are your bad conscience. The White Rose will not leave you in peace!" Lilo Ramdohr remembers Christoph Probst criticising the leaflet as being "too emotional".

At the end of July, 1942, Hans Scholl, Jürgen Wittenstein, Alexander Schmorell and Willi Graf, were sent to the Eastern Front as medics. During their time in Poland and the Soviet Union they witnessed many examples of atrocities being committed by the German Army which made them even more hostile to the government. They were also upset by having to treat so many wounded and dying soldiers. It became clear that Germany was fighting a war it could not win.

Hans Scholl later told his sister Inge about one incident that had a profound impact on him. "During the transport to the front their train had stopped for a few minutes at a Polish station. Along the embankment he saw women and girls bent over and doing heavy men's work with picks. They wore the yellow Star of David on their blouses. Hans slipped through the window of his car and approached. The first one in the group was a young, emaciated girl with small, delicate hands and a beautiful, intelligent face that bore an expression of unspeakable sorrow. Did he have anything that he might give to her? He remembered his Iron Ration - a bar of chocolate, raisins, and nuts - and slipped it into her pocket. The girl threw it on the ground at his feet with a harassed but infinitely proud gesture. He picked it up, smiled, and said, I wanted to do something to please you. Then he bent down, picked a daisy, and placed it and the package at her feet. The train was starting to move, and Hans had to take a couple of long leaps to get back on. From the window he could see that the girl was standing still, watching the departing train, the white flower in her hair."

Scholl, Wittenstein, Graf and Schmorell returned to Munich in November, 1942. The following month Scholl went to visit Kurt Huber and asked his advice on the text of a new leaflet. He had previously rejected the idea of leaflets because he thought they would have no appreciable effect on the public and the danger of producing them outweighed any effect they might have. However, he had changed his mind and agreed to help Scholl write the leaflet. Huber later commented that "in a state where the free expression of public opinion is throttled a dissident must necessarily turn to illegal methods."

Lilo Ramdohr was a member of the White Rose group. Ramdohr arranged for Hans Scholl and Alexander Schmorell to meet her boyfriend, Falk Harnack. Harnack was critical of the leaflets because he thought they "were academic, intellectual, and much too flowery to have an impact on the masses" and had obviously been published by people who "didn't speak the language of the working people." Harnack insisted that the group needed to join forces with those on the left of the political spectrum.

Scholl agreed and Harnack and suggested that they formed a branch of their group in Berlin. "They were eager to establish some kind of contact with the anti-Nazi opposition in Berlin, where efforts were being made to bring together the various factions of the resistance - Communist, liberal, conservative-military - into a unified movement with a consensus on aims and action. Falk Harnack had the necessary connections, including contacts with high-ranking army officers."

The first draft of the fifth leaflet was written by Sophie Scholl, Hans Scholl and Alexander Schmorell. Kurt Huber then revised the material. The three men had long discussions about the content of the leaflet. Huber thought that the young men were "leaning too much to the left" and he described the White Rose group as "a Communist ring". However, it was eventually agreed what would be published. For the first time, the name White Rose did not appear on the leaflet. The authors now presented them as the "Resistance Movement in Germany".

This leaflet, entitled A Call to All Germans!, included the following passage: "Germans! Do you and your children want to suffer the same fate that befell the Jews? Do you want to be judged by the same standards as your traducers? Are we do be forever the nation which is hated and rejected by all mankind? No. Dissociate yourselves from National Socialist gangsterism. Prove by your deeds that you think otherwise. A new war of liberation is about to begin."

It ended with the kind of world they wanted after the war finished: "Imperialistic designs for power, regardless from which side they come, must be neutralized for all time... All centralized power, like that exercised by the Prussian state in Germany and in Europe, must be eliminated... The coming Germany must be federalistic. The working class must be liberated from its degraded conditions of slavery by a reasonable form of socialism... Freedom of speech, freedom of religion, the protection of individual citizens from the arbitrary will of criminal regimes of violence - these will be the bases of the New Europe."

The Gestapo later estimated that the White Rose group distributed around 10,000 copies of this leaflet. Sophie Scholl and Traute Lafrenz purchased the special paper needed, as well as the envelopes and stamps from a large number of shops to avoid suspicion. Each leaflet was turned out one by one, night after night. "In order to stay awake and to function during the day, they took pep pills from the military clinics where the medics worked." (32) The conspirators had to ensure that the Gestapo could not trace the source to Munich so the group had to post their leaflets from neighbouring towns."

The authorities took the fifth leaflet more seriously than the others. One of the Gestapo's most experienced agents, Robert Mohr, was ordered to carry out a full investigation into the group called the "Resistance Movement in Germany". He was told "the leaflets were creating the greatest disturbance at the highest levels of the Party and the State". Mohr was especially concerned by the leaflets simultaneous appearance in widely separated cities including Stuttgart, Vienna, Ulm, Frankfurt, Linz, Salzburg and Augsburg. This suggested an organization of considerable size was at work, one with capable leadership and considerable resources.

On 3rd, 8th and 15th February, 1943, Willi Graf, Hans Scholl and Alexander Schmorell went out into the darkened streets and painted slogans such as "Freedom" and "Down with Hitler!" on the walls of apartment houses, state buildings, and the university. In some places they added a white swastika, crossed out with a smear of red paint. Christoph Probst, who was living in Innsbruck at the time, heard about this, he told his friends that "these nocturnal forays were dangerous and foolish."

On 13th January, 1943, the Gauleiter of Bavaria, Paul Giesler, addressed the students of University of Munich in the Main Auditorium of the Deutsche Museum. He argued that universities should not produce students with "twisted intellects" and "falsely clever minds". Giesler went on to state that "real life is transmitted to us only by Adolf Hitler, with his light, joyful and life-affirming teachings!" He went on to attack "well-bred daughters" who were shirking their war duties. Some women in the audience began calling out angry comments. He responded by arguing that "the natural place for a woman is not at the university, but with her family, at the side of her husband." The female students at the university should fulfill their duties as mothers instead of studying. He then added that "for those women students not pretty enough to catch a man, I'd be happy to lend them one of my adjutants".

Traute Lafrenz and Katharina Schüddekopf began shouting abuse at Giesler. Other women in the audience joined in. Giesler then ordered their arrest by his SS guards. Male students, including Hans Leipelt, came to their aid and fights began all over the auditorium. Those who managed to escape ran out of the museum and after forming themselves in a large group, began marching in a procession in the direction of the university. They linked arms as they marched singing songs of solidarity. However, before they got to the university armed police forced them to disperse.

The White Rose group believed there was a direct connection between their leaflets and the student unrest. They decided therefore to print another 1,300 leaflets and to distribute them around the university. On 18th February, 1943, Sophie and Hans Scholl went to the University of Munich with a suitcase packed with leaflets. According to Inge Scholl: "They arrived at the university, and since the lecture rooms were to open in a few minutes, they quickly decided to deposit the leaflets in the corridors. Then they disposed of the remainder by letting the sheets fall from the top level of the staircase down into the entrance hall. Relieved, they were about to go, but a pair of eyes had spotted them. It was as if these eyes (they belonged to the building superintendent) had been detached from the being of their owner and turned into automatic spyglasses of the dictatorship. The doors of the building were immediately locked, and the fate of brother and sister was sealed."

Jakob Schmid, a member of the Nazi Party, saw them at the University of Munich, throwing leaflets from a window of the third floor into the courtyard below. He immediately told the Gestapo and they were both arrested. They were searched and the police found a handwritten draft of another leaflet. This they matched to a letter in Scholl's flat that had been signed by Christoph Probst. Following interrogation, they were all charged with treason.

Sophie, Hans and Christoph were not allowed to select a defence lawyer. Inge Scholl claimed that the lawyer assigned by the authorities "was little more than a helpless puppet". Sophie told him: "If my brother is sentenced to die, you musn't let them give me a lighter sentence, for I am exactly as guilty as he."

Sophie was interrogated all night long. She told her cell-mate, Else Gebel, that she denied her "complicity for a long time". But when she was told that the Gestapo had found evidence in her brother's room that proved she was guilty of drafting the leaflet. "Then the two of you knew that all was lost... We will take the blame for everything, so that no other person is put in danger." Sophie made a confession about her own activities but refused to give information about the rest of the group.

The trial took place on 22nd February, 1943. The indictment against Christoph Probst stated: "Early in 1943 the accused Hans Scholl requested that his friend, the accused Probst (with whom he had for a long time exchanged ideas about the political situation), write down his ideas on current political developments. Probst then sent him a draft, which without doubt was to be duplicated and distributed, though there was no time for such action. This draft was found in Scholl's pocket at the time of his arrest."

Judge Roland Freisler argued in court that Probst was guilty of producing "in cowardly defeatism" a leaflet "which takes the heroic struggle in Stalingrad as the occasion for defaming the Führer as a military swindler and which then, progressing to a hortatory tone, calls for opposition to National Socialism and for action which would lead, as he pretends, to an honorable capitulation. He supports the promises in this leaflet by citing-Roosevelt! And his knowledge about these matters he derived from listening to British broadcasts!."

Freisler added that Probst's defence was that he had not intended the material to be used as a leaflet was not convincing or acceptable: "Whoever acts in this way - and particularly at this time, when we must close our ranks - is attempting to cause the first rift in the unity of the battle front. And German students, whose traditional honor has always called for self-sacrifice for Volk and fatherland, were the ones who acted thus!"

Friends of Hans and Sophie had immediately telephoned Robert Scholl with news of the arrests. Robert and Magdalena went to Gestapo headquarters but they were told they were not allowed to visit them in prison over the weekend. They were not told that there trial was to begin on the Monday morning. However, another friend, Otl Aicher, telephoned them with the news. They were met by Jürgen Wittenstein at the railway station: "We have very little time. The People's Court is in session, and the hearing is already under way. We must prepare ourselves for the worst."

Sophie's parents tried to attend the trial and Magdalene told a guard: "I’m the mother of two of the accused." He responded: "You should have brought them up better." Robert Scholl was forced his way past the guards at the door and managed to get to his children's defence attorney. "Go to the president of the court and tell him that the father is here and he wants to defend his children!" He spoke to Judge Roland Freisler who responded by ordering the Scholl family from the court. The guards dragged them out but at the door Robert was able to shout: "There is a higher justice! They will go down in history!"

Later that day Sophie Scholl, Hans Scholl and Christoph Probst were all found guilty. Judge Freisler told the court: "The accused have by means of leaflets in a time of war called for the sabotage of the war effort and armaments and for the overthrow of the National Socialist way of life of our people, have propagated defeatist ideas, and have most vulgarly defamed the Führer, thereby giving aid to the enemy of the Reich and weakening the armed security of the nation. On this account they are to be punished by death. Their honour and rights as citizens are forfeited for all time."

Werner Scholl was in court in his German Army uniform. He managed to get to his brother and sister. "He shook hands with them, tears filling his eyes. Hans was able to reach out and touch him, saying quickly, Stay strong, no compromises."

Robert and Magdalena managed to see their children before they were executed. Their daughter, Inge Scholl, later explained what happened: "First Hans was brought out. He wore a prison uniform, he walked upright and briskly, and he allowed nothing in the circumstances to becloud his spirit. His face was thin and drawn, as if after a difficult struggle, but now it beamed radiantly. He bent lovingly over the barrier and took his parents' hands... Then Hans asked them to take his greetings to all his friends. When at the end he mentioned one further name, a tear ran down his face; he bent low so that no one would see. And then he went out, without the slightest show of fear, borne along by a profound inner strength."

Magdalena Scholl said to her 22 year-old daughter: "I'll never see you come through the door again." Sophie replied, "Oh mother, after all, it's only a few years' more life I'll miss." Sophie told her parents she and Hans were pleased and proud that they had betrayed no one, that they had taken all the responsibility on themselves.

Else Gebel shared Sophie Scholl's cell and recorded her last words before being taken away to be executed. "How can we expect righteousness to prevail when there is hardly anyone willing to give himself up individually to a righteous cause.... It is such a splendid sunny day, and I have to go. But how many have to die on the battlefield in these days, how many young, promising lives. What does my death matter if by our acts thousands are warned and alerted. Among the student body there will certainly be a revolt."

They were all beheaded by guillotine in Stadelheim Prison only a few hours after being found guilty. A prison guard later reported: "They bore themselves with marvelous bravery. The whole prison was impressed by them. That is why we risked bringing the three of them together once more-at the last moment before the execution. If our action had become known, the consequences for us would have been serious. We wanted to let them have a cigarette together before the end. It was just a few minutes that they had, but I believe that it meant a great deal to them."

The Gestapo began arresting other members of the White Rose group. Alexander Schmorell went to see Lilo Ramdohr who allowed him to stay the night. She was able to get hold of a Yugoslav passport from a friend who was a printer and had the photo replaced with one of Schmorell. His plan was to travel to Switzerland. However, when he arrived at the railway station he discovered that all papers and train tickets were being checked by the police.

Schmorell attempted to get help from people not connected to the White Rose group but when he visited a friend, Marie Luise, she contacted the police. Schmorell made a full confession and admitted duplicating and distributing the leaflets: "Schmorell traveled to Salzburg, Linz, and Vienna and put leaflets addressed to places in those cities in the mails." He also said he was responsible for "defacing walls in many places in Munich" with the words "Down With Hitler", "Hitler the Mass Murderer" and "Freedom".

Willi Graf, Alexander Schmorell and Kurt Huber were all arrested. The Gestapo interviewed Graf for several days and nights. He willingly admitted his guilt but refused to give the names of other members of the White Rose group. It was later claimed that "brilliant lights were beamed into his eyes constantly as three voices questioned him in irregular, unpredictable patterns".

Several members of the White Rose group were put on trial on 19th April, 1943. This included Alexander Schmorell, Kurt Huber, Willi Graf, Traute Lafrenz, Hans Hirzel, Susanne Hirzel, Falk Harnack, Eugen Grimminger, Heinrich Bollinger, Helmut Bauer, Franz Müller, Heinrich Guter, Gisela Schertling and Katharina Schüddekopf. (59)

At the beginning of the trial, the lawyer representing Huber leaped to his feet at the beginning of the trial, raised his arm in the Nazi salute, and shouted "Heil Hitler!" He then announced that he was disassociating himself from his client: "This is the first time I have heard the contents of these leaflets. As a German and a protector of the law of the German Reich, I cannot tolerate such vilification of the Führer. I cannot defend such a monstrous crime. I respectfully ask this court to be relieved of the obligation to defend my client."

Judge Roland Freisler replied: "This court thoroughly understands your position. You may lay down your brief." Freisler ordered another attorney present to represent Kurt Huber. This lawyer protested that he didn't know the case, had not examined the evidence. Freisler waved away the objections. Huber was also upset by the news that other academics had refused to serve as character witnesses."

Kurt Huber, Alexander Schmorell and Willi Graf were all charged with high treason. "Kurt Huber, Alexander Schmorell and Willi Graf in time of war have promulgated leaflets calling for sabotage of the war effort and for the overthrow of the National Socialist way of life of our people; have propagated defeatist ideas, and have most vulgarly defamed the Führer, thereby giving aid to the enemy of the Reich and weakening the armed security of the nation."

The indictment againt Graf and Schomorell stated that both men should "have been particularly grateful to the Führer, for he ordered army pay for them during the time of their university attendance - as was true for all enlistees assigned to medical study. Inclusive of money for food, they received over 250 marks per month, and exclusive of money for food, but with rations in goods, it still amounted to about 200 marks - more than most students ordinarily receive from home". He was accused of distributing leaflets and recruiting others "for anti-German projects".

Willi Graf said almost nothing in his defence when he appeared in the dock. Judge Roland Freisler told Graf that he "had the Gestapo running in circles for a while... but in the end we were too smart for you, weren't we?" "Graf stood tall, pale, his features closed, his blue eyes remote". When he refused to answer questions Freisler ordered him to leave the dock. "Graf sat down, his eyes blank; it was as if his spirit had left the chamber."

Kurt Huber gave a speech in the court. He tried to explain his sense of responsibility as a German professor. "As a German citizen, as a German professor, and as a political person, I hold it to be not only my right but also my moral duty to take part in the shaping of our German destiny, to expose and oppose obvious wrongs. What I intended to accomplish was to rouse the student body, not by means of an organization, but solely by my simple words; to urge them, not to violence, but to moral insight into the existing serious deficiencies of our political system. To urge the return to clear moral principles, to the constitutional state, to mutual trust between men."

He finished with the words: "You have stripped from me the rank and privileges of the professorship and the doctoral degree which I earned, and you have set me at the level of the lowest criminal. The inner dignity of the university teacher, of the frank, courageous protestor of his philosophical and political views - no trial for treason can rob me of that. My actions and my intentions will be justified in the inevitable course of history; such is my firm faith. I hope to God that the inner strength that will vindicate my deeds will in good time spring forth from my own people. I have done as I had to on the prompting of my inner voice."

Judge Roland Freisler responded: "A German university professor is first and foremost an educator of the young. As such he ought to try, in time of difficulty and struggle, to see that our university students are trained to be worthy younger brothers of the soldiers of 1914 at Langemarck in Flanders; that they are reinforced in their absolute trust in our Führer, our people and our Reich; and that they become seasoned fighters, prepared for any sacrifice! The accused Huber, however, acted in an exactly opposite manner! He nourished doubt instead of dispelling it; he delivered addresses about federalism and democracy for Germany, about a multiparty system, instead of teaching and setting an example in his own life of rigorous National Socialism. It was not a time for tackling theoretical problems, but rather for grasping the sword, yet he sowed doubt among our youth.... Huber further states that he believed he was performing a good deed... The days when every man can be allowed to profess his own political beliefs are past. For us there is but one standard: the National Socialist one. Against this we measure each man!"

Willie Graf, Kurt Huber and Alexander Schmorell were all convicted of high treason and were all sentenced to death. Other sentences included Eugen Grimminger, ten years; Heinrich Bollinger and Helmut Bauer, seven years; Hans Hirzel and Franz Müller, five years; Heinrich Guter, eighteen months; Susanne Hirzel, six months; Traute Lafrenz, Gisela Schertling and Katharina Schüddekopf, one year each.

Falk Harnack was surprisingly found not guilty. Judge Roland Freisler commented: "Falk Harnack failed to report his knowledge of treasonous activity. But such unique and special circumstances surround his case that we find ourselves unable to punish his deed of omission. He is accordingly set free."