Oswald Mosley and Fascism in Britain

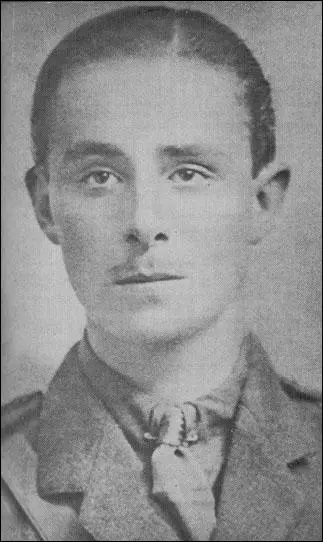

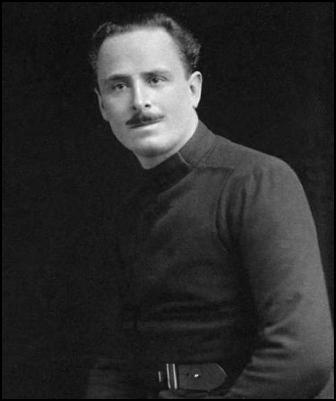

Oswald Mosley, the eldest of the three sons of Sir Oswald Mosley (1874–1928), who succeeded to the baronetcy in 1915, and his wife, Maud Mosley (1874–1950), was born on 16th November 1896. When he was five his mother moved out of the family home. According to his son, Nicholas Mosley, "she left her husband on account of his insatiable and promiscuous sexual habits." (1)

Robert Skidelsky claims there was another reason for her actions: "When Mosley was five Maud Mosley obtained a judicial separation from her husband on account of the latter's infidelities and possibly also to protect Tom, as she called her eldest son, from his father's bullying. Thereafter his childhood was divided between his mother's modest house near her family home in Shropshire and the massive neo-Gothic pile of Rolleston Hall... Mosley adored his mother and his paternal grandfather, who in turn worshipped him. To his mother, a pious, fiercely loyal woman, he was a substitute for an absent husband." (2)

At the age of nine he was sent away to West Down, a small preparatory school. Four years later he entered Winchester College. An excellent sportsman he was trained to box and fence by two ex-army NCOs. At fifteen he won the public schools' fencing championship in both foil and sabre. He was less successful with his academic work. He wrote in his autobiography: "Apart from games, the dreary waste of public school existence was only relieved by learning and homosexuality; at that time I had no capacity for the former and I never had any taste for the latter." (3)

Mosley was considered to be a strange boy by the other students and had no friends, but he was not bullied because he was a good boxer. "To most boys in his house he appeared stupid, or at least totally uninterested in work... At a time when most fourteen-year-olds are merely pretty, Mosley was already handsome." He hated taking orders for the teachers and older students. One of the other boys recalls him as "very tall, with striking, dark good looks: he could easily have been made into a stage villain." (4)

Oswald Mosley and the First World War

In January 1914 Oswald Mosley became an officer cadet at Sandhurst, which he entered as an officer cadet. "What the cadets liked to do in the evenings was to pile into cars (this was 1913) and go up to London and there provoke fights with the chukers-out at places like the Empire Music Hall... The gangs of toughs, however, were apt to fight amongst themselves. In one dispute about a polo pony there were insults, threats of horse-whippings, violence, and in the subsequent fracas my father, fell from the ledge of an upstairs window and injured his leg." (5).

On the outbreak of the First World War he was commissioned in the 16th Lancers, a cavalry regiment. He spent time in Ireland and then, because there did not seem to be much chance of the cavalry being used in the war, he volunteered to join the newly formed Royal Flying Corps who were in need of observers. Mosley wanted more action and he trained to become a pilot. He knew the chances of being killed was fairly high: "We were like men having dinner together at a country house-party knowing that some must soon leave us for ever; in the end, nearly all." (6)

Mosley wrote to his mother not to grieve if he was killed as he was sure he would find death "a most interesting experience". However, while showing off before his mother at Shoreham Airport in May 1915 he crashed his plane and broke his right ankle. He was now sent to fight on the Western Front. However, his leg failed to heal and he was sent home for further operations which saved his leg but left him with a permanent limp and, by October 1916, it was decided that Lieutenant Mosley was only fit for desk work. (7)

Mosley spent the rest of the war working in the Ministry of Munitions and the Foreign Office. He developed a keen interest in politics and he later wrote about his feelings when the Armistice was signed on 11th November, 1918: "I passed through the festive streets and entered one of London's largest and most fashionable hotels, interested by the sounds of revelry which echoed from it. Smooth, smug people, who had never fought or suffered, seemed to the eyes of youth - at that moment age-old with sadness, weariness and bitterness - to be eating, drinking, laughing on the graves of our companions. I stood aside from the delirious throng; silent and alone, ravaged by memory. Driving purpose had begun; there must be no more war. I dedicated myself to politics." (8)

Oswald Mosley in the House of Commons

Oswald Mosley spent his time studying the lives of famous English politicians. This included William Pitt, Charles Fox, William Gladstone and Benjamin Disraeli. He also arranged to meet leading politicians at the time including Winston Churchill, Herbert Asquith, and Frederick E. Smith. Mosley also became friends with Harold Nicolson, the private secretary of Lord Curzon, the Foreign Secretary. Both leading political parties attempted to recruit him but he eventually joined the Conservative Party over the Liberal Party. (9)

Mosley was selected for the safe-seat of Harrow. In the Harrow Observer it was claimed that Mosley was a Central Office nominee, foisted onto the Harrow Association at the expense of better-qualified local men. In one letter, a local solicitor, A. R. Chamberlayne, attacked the "party caucus" which was able to foist men of wealth and connection onto the local associations. Mosley responded by describing Chamberlayne as a failed politician. (10)

Mosley was a great supporter of the idea that Germany had to be treated harshly after the war: "Even if we discount the possibility of another war in our time... the prospect is not alluring, for ultimate German domination of the world would be assured in an economic if not in a military form... Germany (if treated well in the peace agreement) would become one vast business firm, concentrated on one object, to undersell and crush all competitors in every market of the world." (11)

David Lloyd George, the prime minister, was determined to have a general election as soon as possible after the Armistice. King George V wanted the election to be delayed until the public bitterness towards Germany and the desire for revenge had faded, but Lloyd George insisted on going to the country in the "warm after-glow of victory". It was announced that the 1918 General Election would take place on 12th December. (12)

David Lloyd George did a deal with Arthur Bonar Law that the Conservative Party would not stand against Liberal Party members who had supported the coalition government and had voted for him in the Maurice Debate. It was agreed that the Conservatives could then concentrate their efforts on taking on the Labour Party and the official Liberal Party that supported their former leader, Herbert Asquith. The secretary to the Cabinet, Maurice Hankey, commented: "My opinion is that the P.M. is assuming too much the role of a dictator and that he is heading for very serious trouble." (13)

During the campaign Mosley called on German aliens to be deported and that Kaiser Wilhelm II should be tried for war crimes. Germany should be squeezed "until the pips squeaked". He claimed that "Germans had brought disease amongst them, reduced Englishmen's wages, undersold English goods, and ruined social life." (14)

The result announced a fortnight later (to allow for a postal military vote) gave Mosley 13,950, his opponent 3,007. Aged 22, he became the youngest MP in the House of Commons. The local newspaper reported: "It must be said of the successful candidate that he fought for all he was worth... Buoyed up by an ambition for a political career, for which he gives much real promise, he has triumphantly succeeded." (15)

In May 1920 Mosley married Lady Cynthia Curzon, the second daughter of the foreign secretary, Lord Curzon of Kedleston, the former Viceroy of India. Mosley had numerous affairs, including relationships with his wife's younger sister Alexandra Metcalfe (1904-1995), and with their stepmother, Grace Curzon (1879-1958). "Their life together started on a high note of mutual passion which was not, however, sustained. Cimmie, as she was always known, was an idealistic, emotional, not very clever woman, who idolized her husband, and wanted to be adored and cherished in return. Mosley's love for her was genuine, and fervently expressed in letters full of baby talk, written in an illegible hand. But he was incapable of fidelity, resented her minding about his love affairs, and he abused her in public for what he saw as her simplicities." (16)

Mosley was not a loyal Conservative and in his maiden speech he made an attack on the government, including Winston Churchill, secretary of state for war and air. Stanley Baldwin, a fellow Tory MP, commented: "He's a cad and a wrong'un and they will find out." According to Jim Wilson: "Mosley had emerged from the war a dashing figure, much in demand by political hostesses, with a barely disguised contempt for what he regarded as middle-class morality; blandly describing his well-known pursuit of married women as flushing the covers." (17)

Mosley often expressed left of centre political views. In 1921 he argued against spending money on trying to overthrow the Bolshevik government in Russia. "It went to my heart to think of £100,000,000 being spent in Russia supporting a mere adventure", while the unemployed "are trying to keep a family on 15s. a week". He went on to argue that "it is evident that great economies can be effected by cutting adrift from all extraneous adventures and commitments, and withdrawing to the normal bounds of Empire." (18)

Oswald Mosley and Ireland

Mosley also became a critic of the government's policy in Ireland. An estimated 10% of the Royal Irish Constabulary resigned between August 1918 and August 1920. Winston Churchill, the Secretary of State for War, suggested that that the government should recruit British ex-servicemen to serve as policemen in Ireland. Over the next few weeks 4,400 men, who received the good wage of 10 shillings a day, joined the Royal Irish Constabulary Special Reserve. They obtained the nickname, Black and Tans, from the colours of the improvised uniforms they initially wore, composed of mixed khaki British Army and rifle green RIC uniform parts. (19)

Complaints were soon received about the behaviour of the Black and Tans and the government was attacked in the House of Commons by the Labour Party for using terror tactics. David Lloyd George rejected these claims in a speech where he denounced the insurgency as "organized assassination of the most cowardly kind" but assured his audience, that "we have murder by the throat". (20)

In October 1920, Mosley in the House of Commons condemned the behaviour of the Black and Tans. "The Government was confusing the right of men to defend themselves with the right to wander around the countryside, destroying the houses and the property of innocent persons, and depriving them of any possible means of earning a livelihood... You will not restore order in Ireland by pulling old women out of their beds and burning their houses." He added that the only way to break down the murder gangs "is to catch them... you must obtain information of their movements... You must act upon it." (21)

The Cairo Gang was a group of British intelligence agents who were sent to Dublin with the intention of assassinating leading members of the IRA. Unfortunately, the IRA had a spy in the ranks of the RIC and twelve members of this group, were killed on the morning of 21st November 1920 in a planned series of simultaneous early-morning strikes engineered by Michael Collins. The men killed included Colonel Wilfrid Woodcock, Lieutenant-Colonel Hugh Montgomery, Major Charles Dowling, Captain George Bennett, Captain Leonard Price, Captain Brian Keenlyside, Captain William Newberry, Lieutenant Donald MacLean, Lieutenant Peter Ames, Lieutenant Henry Angliss and Lieutenant Leonard Wilde. (22)

That afternoon the Royal Irish Constabulary drove in trucks into Croke Park during a football match, shooting into the crowd. Fourteen civilians were killed, including one of the players, Michael Hogan, and a further 65 people were wounded. Later that day two republicans, Richard McKee, Peadar Clancy and an unassociated friend, Conor Clune were arrested and after being tortured were shot dead "while trying to escape". (23)

Mosley continued to criticise government policy in Ireland. Mosley claimed that it was the gross inefficiency of government policy "which has been largely responsible for the death of many of these gallant men". These men had died as a result of the actions of the Black and Tans. He argued that there was "overwhelming evidence.. that this policy of reprisals is a deliberate purpose" and that David Lloyd George "had obliterated the narrow, but very sacred line, which divides justice from indiscriminate revenge". (24)

The government was furious with Mosley for making this speech. However, it was welcomed by members of the Liberal Party and the Labour Party. One veteran MP, William Wedgwood Benn, described it "one of the best speeches I have ever heard in the House". Mosley joined forces with a group of left-wing political figures that included Ramsay MacDonald, George Douglas Cole, Ben Tillett, Sidney Webb, and Leonard Woolf, to form a Peace with Ireland Council that promised to acquire information on individual atrocities perpetrated by the Black and Tans. (25)

Mosley stands as an Independent

Mosley came under pressure from the Harrow Conservative Association to support the government in the House of Commons. Mosley refused: "I cannot enter Parliament unless I am free to take any action of opposition or association, irrespective of labels, that is compatible with my principles and is conductive to their success. My first consideration must always be the triumph of the causes for which I stand and in the present condition of politics, or in any situation likely to arise in the near future, such freedom of action is necessary to that end." (26)

At a meeting on 14th October, 1922, two younger members of the government, Stanley Baldwin and Leo Amery, urged the Conservative Party to remove David Lloyd George from power. Andrew Bonar Law disagreed as he believed that he should remain loyal to the Prime Minister. In the next few days Bonar Law was visited by a series of influential Tories - all of whom pleaded with him to break with Lloyd George. This message was reinforced by the result of the Newport by-election where the independent Conservative won with a majority of 2,000, the coalition Conservative came in a bad third.

Another meeting took place on 18th October. Austen Chamberlain and Arthur Balfour both defended the coalition. However, it was a passionate speech by Baldwin: "The Prime Minister was described this morning in The Times, in the words of a distinguished aristocrat, as a live wire. He was described to me and others in more stately language by the Lord Chancellor as a dynamic force. I accept those words. He is a dynamic force and it is from that very fact that our troubles, in our opinion, arise. A dynamic force is a terrible thing. It may crush you but it is not necessarily right." The motion to withdraw from the coalition was carried by 187 votes to 87. (27)

Oswald Mosley decided to stand in Harrow as an Independent in the 1922 General Election. The Labour and Liberal parties did not stand against him and he increased the size of his majority by polling 15,290 against 7,868 for the Tory candidate. However, the Conservative Party won 344 seats and formed the next government. The Labour Party promised to nationalise the mines and railways, a massive house building programme and to revise the peace treaties, went from 57 to 142 seats, whereas the Liberal Party increased their vote and went from 36 to 62 seats. The major loser was the Lloyd George Liberals. (28)

Beatrice Webb, a senior figure in the Labour Party, met Mosley for the first time in June, 1923: "We have made the acquaintance of the most brilliant man in the House of Commons - Oswald Mosley.... If there were a word for the direct opposite of a caricature, for something which is almost absurdly a perfect type, I should apply it to him. Tall and slim, his features not too handsome to be strikingly peculiar to himself, modest yet dignified in manner, with a pleasant voice and unegotistical conversation, this young person would make his way in the world without his adventitious advantages, which are many - birth, wealth and a beautiful aristocratic wife. He is also an accomplished orator in the old grand style, and an assiduous worker in the modern manner - keeps two secretaries at work supplying him with information but realizes that he himself has to do the thinking!" (29)

Mosley was now in a difficult position. As Robert Skidelsky pointed out: "He (Mosley) might be able to go on holding Harrow for ever, but he could scarcely expect to make his mark on his time as an eccentric Independent of mildly left-wing opinions." Attempts were made to persuade him to join the two main opposition parties. However, he was uncertain which one would give him a route to power and when Stanley Baldwin called another election in November, 1923, he decided to fight it as an Independent. He held the seat but with a reduced majority of 4,646. (30)

In the 1923 General Election, the Labour Party won 191 seats. David Marquand has pointed out that: "The new parliamentary Labour Party was a very different body from the old one. In 1918, 48 Labour M.P.s had been sponsored by trade unions, and only three by the ILP. Now about 100 members belonged to the ILP, while 32 had actually been sponsored by it, as against 85 who had been sponsored by trade unions.... In Parliament, it could present itself for the first time as the movement of opinion rather than of class." (31)

Although the Conservative Party had 258 seats, Herbert Asquith announced that the Liberal Party would not keep the Tories in office. If a Labour Government were ever to be tried in Britain, he declared, "it could hardly be tried under safer conditions". The Daily Mail warned about the dangers of a Labour government and the Daily Herald commented on the "Rothermere press as a frantic attempt to induce Mr Asquith to combine with the Tories to prevent a Labour Government assuming office". (32)

On 22nd January, 1924 Stanley Baldwin resigned. At midday, the 57 year-old, Ramsay MacDonald went to Buckingham Palace to be appointed prime minister. He later recalled how George V complained about the singing of the Red Flag and the La Marseilles, at the Labour Party meeting in the Albert Hall a few days before. MacDonald apologized but claimed that there would have been a riot if he had tried to stop it. (33)

Oswald Mosley joins the Labour Party

It now became clear which party he must join to have a successful political career. On 27th March 1924, Oswald Mosley applied to join the Labour Party. The Liberals reacted angrily to the decision and Margot Asquith wrote to him: "Personally I think you have done an unwise thing at a foolish time, but after all this is your own affair and not mine. You had a very great - if not the greatest chance in the future of leading the Liberal Party... You need courage and conviction to achieve anything big in politics and above all patience and a certain amount of education. Till now I have seen none of these qualities in the new Government." She finished her letter by saying she recently visited Italy: "I had a wonderful time with Mussolini who is a really Big Man." (34)

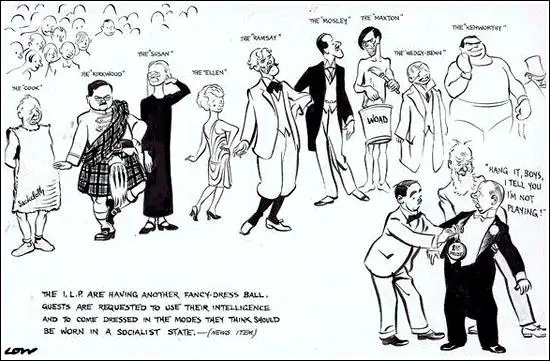

Ramsay MacDonald was extremely pleased by Mosley decision as it thought his aristocratic background would help the Labour Party to appear "respectable". Mosley immediately joined the Independent Labour Party, the left-wing pressure group in the Labour Party. Some members of the ILP were highly suspicious of his motives. Willie Stewart, a veteran member, commented: "He'll need watching, he's out of a bad nest." Others in the party such as Herbert Morrison and Hugh Dalton "were naturally jealous of a rich recruit who entered with such a fanfare of publicity and felt that their own years of patient toil in the cause had been undervalued by comparison." (35)

Egon Ranshofen-Wertheimer, was a German journalist who saw Mosley speak at a Labour Party public meeting in April, 1924: "Suddenly there was a movement in the crowd, and a young man, with the face of the ruling class in Great Britain, but the gait of a Douglas Fairbanks, thrust himself forward through the throng to the platform, followed by a lady in heavy, costly furs. There stood Oswald Mosley... a new recruit to the Socialist movement at his first London meeting. He was introduced to the audience, and even at that time, I remember, the song 'For he's a jolly good fellow', greeted the young man from two thousand throats." (36)

Oswald Mosley decided to stand at Ladywood, Birmingham, a seat held by Neville Chamberlain in the 1924 General Election. During the campaign it became clear that Mosley had a good chance of winning the seat. A local journalist wrote: "None of us who went through that fight with him will ever forget it. His power of the audience was amazing, and his eloquence made even hardened Pressmen gasp in astonishment." Mosley commented: "It was a joyous day when in the courtyards running back from the streets in the Birmingham slums we saw the blue window cards coming down and the red going up." (37)

However, four days before the election, The Daily Mail published the Zinoviev Letter. Under the headline "Civil War Plot by Socialists Masters" it argued: "Moscow issues orders to the British Communists... the British Communists in turn give orders to the Socialist Government, which it tamely and humbly obeys... Now we can see why Mr MacDonald has done obeisance throughout the campaign to the Red Flag with its associations of murder and crime. He is a stalking horse for the Reds as Kerensky was... Everything is to be made ready for a great outbreak of the abominable class war which is civil war of the most savage kind." (38)

The rest of the Tory owned newspapers ran the story about the letter (although later it was discovered to be a forgery) over the next few days and it was no surprise when the election was a disaster for the Labour Party. The Conservatives won 412 seats and formed the next government. Lord Beaverbrook, the owner of the Daily Express and Evening Standard, told Lord Rothermere, the owner of The Daily Mail and The Times, that the "Red Letter" campaign had won the election for the Conservatives. Rothermere replied that it was probably worth a hundred seats. (39)

Mosley was defeated by only 77 votes. He now became a leading advocate for socialism. He worked very closely with John Strachey, who had also come from a very privileged background. Both men were according to Hugh Thomas, "refugees from the upper class" in a largely proletarian or lower-middle-class world, who were "intoxicated" by "sexual freedom". (40)

Mosley and Strachey both read and impressed with the work of John Maynard Keynes. Mosley attempted to adapt Keynes' theories to his ideas on socialism. At an Independent Labour Party conference at Gloucester, he called for the nationalisation of the banking system "that consecrated combination of private interests and public plunders". The banking system, Mosley explained, lay at the heart of capitalism. "Every capitalist must come to you and you can dictate the conditions under which he will carry on... Let us join to our cry for the minimum wage the battle cry, the banks for the people." (41)

On 3rd May 1925, introduced his "unauthorised economic programme" to Birmingham. Over 5,000 people queued for seats in the Birmingham Town Hall, which seated only half that number. He attacked the government policy of forcing down wages in order to make the workers more employable. Stanley Baldwin had recently claimed that "all the workers of this country have got to face a reduction of wages". Mosley argued that the workers should have their wages raised as it would help stimulate employment. (42)

This message was repeated in another speech the following month by John Strachey. "The cause of poverty was that not enough necessaries were being produced; and when employers were asked why they did not produce more, they replied that it was because there was no effective demand." Strachey argued that the government needed to get control of the banking system and force up wages, thus creating the demand which manufacturers would then supply. (43)

Smethwick By-Election

On 22nd November, John Davison, the Labour MP for Smethwick, was forced to resign on grounds of ill-health. Mosley was immediately selected to replace Davison. This was a controversial decision and some Labour politicians pointed out that the party had been formed to represent the working-class. Philip Snowden, who was opposed to Mosley's economic policies, warned the party not to "degenerate into an instrument for the ambitions of wealthy men" and suggested that some candidatures were being "put up to auction by the local Labour Party and sold to the highest bidder". (44)

Mosley also came under attack from Conservative supporting newspapers. They were at different times accused of "flaunting their wealth or adopting heavy proletarian camouflage - and which was the more reprehensible". For example, The Daily Express accused Mosley of preaching socialism "in a twenty guineas Savile Row suit". Then he was condemned for "playing his part well" in an "old overcoat and a battered hat and calling Lady Cynthia "the missus". (45)

Other newspapers wrote articles about the wealthy socialist couple frolicking on the Riviera, spending thousands of pounds in renovating their "mansion" and generally "living a debauched aristocratic life". (46) It has been claimed that these attacks motivated his supporters to work even harder. Mosley argued that: "While I am being abused by the Capitalist Press I know I am doing effective work for the Labour cause." (47)

Oswald Mosley's father joined in those criticizing the candidate. The Daily Mail published a letter from him complaining about Mosley's socialism: "More valuable help would be rendered to the country by my Socialist son and daughter-in-law if, instead of achieving cheap publicity about relinquishing titles, they would take more material action and relinquish some of their wealth and so help to make easier the plight of some of their more unfortunate followers". (48)

He followed this by giving an interview to The Daily Express. "He was born with a golden spoon in his mouth - it cost £100 in doctor's fees to bring him into the world. He lived on the fat of the land and never did a day's work in his life. If he and his wife want to go in for Labour, why don't they do a bit of work themselves? My son tells the tale that he does this and that but he lives in the height of luxury. If the working class... are going to be taken in by such nonsense - I am sorry for them. How does my son know anything about them?" (49)

Newspapers owned by Harold Harmsworth (Lord Rothermere) and William Maxwell Aitken (Lord Beaverbrook) reported that Mosley was part of a "Red Plot" and that William Gallagher and Arthur McManus, leading members of the Communist Party of Great Britain, were campaigning for the Labour candidate. The Morning Post complained that "no tactics too contemptible for the Socialists to adopt in their grovelling appeal to all that is most stupid and most deplorable in human nature". (50)

These tactics did not stop him winning Smethwick. His majority of 6,582 on a 80% poll surprised even his most optimistic supporters. To a crowd of 8,000 outside the Town Hall he said that the result was a defeat of the Press Lords: "This is not a by-election, it is history. The result of this election sends out a message to every worker in the land. You have met and beaten the Press of reaction... Tonight all Britain looks to you and thanks you. My wonderful friends of Smethwick, by your heroic battle against a whole world in arms, I believe you have introduced a new era for British democracy." (51)

1929 General Election

Mosley's victory excited some members of the Labour Party. He was a great campaigner and that he had the ability to attract large crowds to public meetings. In October 1927 Mosley was elected to the National Executive Committee of the Labour Party with 1,613,000 votes, behind George Lansbury (2,183,000) and Charles Trevelyan (1,675,000). John Wheatley described him in 1926 as "one of the most brilliant and hopeful figures thrown up by the Socialist Movement during the last 30 years". (52)

Ramsay MacDonald was also impressed with Mosley and had the makings of a great party leader. In October 1928, MacDonald and Mosley went on a motor-car tour together that included visits to Prague, Berlin and Vienna. Mosley was also introduced to one of MacDonald's mistresses who was living in Europe. This holiday led to rumours that MacDonald was introducing a future Labour foreign secretary to European statesmen. (53)

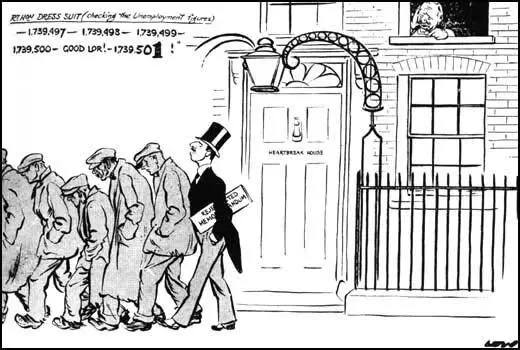

In January 1929, 1,433,000 people in Britain were out of work. Stanley Baldwin was urged to take measures that would protect the depressed iron and steel industry. Baldwin ruled this out owing to the pledge against protection which had been made at the 1924 election. Agriculture was in an even worse condition, and here again the government could offer little assistance without reopening the dangerous tariff issue. Baldwin was considered to be a popular prime minister and he fully expected to win the general election that was to take place on 30th May. (54)

In its manifesto the Conservative Party blamed the General Strike for the country's economic problems. "Trade suffered a severe set-back owing to the General Strike, and the industrial troubles of 1926. In the last two years it has made a remarkable recovery. In the insured industries, other than the coal mining industry, there are now 800,000 more people employed and 125,000 fewer unemployed than when we assumed office... This recovery has been achieved by the combined efforts of our people assisted by the Government's policy of helping industry to help itself. The establishment of stable conditions has given industry confidence and opportunity." (55)

The Labour Party attacked the record of Baldwin's government: "By its inaction during four critical years it has multiplied our difficulties and increased our dangers. Unemployment is more acute than when Labour left office.... The Government's further record is that it has helped its friends by remissions of taxation, whilst it has robbed the funds of the workers' National Health Insurance Societies, reduced Unemployment Benefits, and thrown thousands of workless men and women on to the Poor Law. The Tory Government has added £38,000,000 to indirect taxation, which is an increasing burden on the wage-earners, shop-keepers and lower middle classes." (56)

Oswald Mosley became an important figure in the campaign. During the election he made a speech attacking Baldwin's government: "Unemployment, wages, rents, suffering, squalor and starvation; the struggle for existence in our streets, the threat of world catastrophe in another war; these are the realities of the present age. These are the problems which require every exertion of the best brains of our time for a vast constructive effort. These are the problems which should unite the nation in a white heat of crusading zeal for their solution. But these are precisely the problems which send Parliament to sleep. When not realities but words are to be discussed Parliament wakes up. Then we are back in the comfortable pre-war world of make-believe. Politics are safe again; hairs are to be split, not facts to be faced. Hush! Do not awaken the dreamers. Facts will wake them in time with a vengeance." (57)

A massive campaign in the Tory press against the proposal of increased public spending proposed by Mosley was very successful. In the 1929 General Election the Conservatives won 8,656,000 votes (38%), the Labour Party 8,309,000 (37%) and the Liberals 5,309,000 (23%). However, the bias of the system worked in Labour's favour, and in the House of Commons the party won 287 seats, the Conservatives 261 and the Liberals 59, and MacDonald formed the next government.

It was hoped that MacDonald would increase government spending in order to reduce unemployment but this did not happen. A. J. P. Taylor has argued that the idea of increasing public spending would be good for the economy, was difficult to grasp. "It seemed common sense that a reduction in taxes made the taxpayer richer... Again it was accepted doctrine that British exports lagged because costs of production were too high; and high taxation was blamed for this about as much as high wages." (58). John Maynard Keynes later commented: "The difficulty lies, not in the new ideas, but in escaping from the old ones, which ramify, for those brought up as most of us have been, into every corner of our minds." (59)

Instead of being appointed Foreign Secretary (that job went to Arthur Henderson) Mosley was given a fairly junior position, the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. This surprised some people in the Labour Party. Aneurin Bevan thought he was a potential leader of the party. However, Jennie Lee, the recently elected MP for North Lanarkshire, later pointed out: "Another bright light in this 1929 Parliament was Sir Oswald Mosley." However, she added that "he had a fatal flaw in his character, on overwhelming arrogance and an unshakable conviction that he was born to rule." (60)

Mosley Memorandum

In January 1930 unemployment in Britain reached 1,533,000. By March, the figure was 1,731,000. Oswald Mosley proposed a programme that he believed would help deal with the growing problem of unemployment in Britain. According to David Marquand: "It made three main assertions - that the machinery of government should be drastically overhauled, that unemployment could be radically reduced by a public-works programme on the lines advocated by Keynes and the Liberal Party, and that long-term economic reconstruction required a mobilisation of national resources on a larger scale than has yet been contemplated. The existing administrative structure, Mosley argued, was hopelessly inadequate. What was needed was a new department, under the direct control of the prime minister, consisting of an executive committee of ministers and a secretariat of civil servants, assisted by a permanent staff of economists and an advisory council of outside experts." (61)

The Chancellor of the Exchequer, Philip Snowden, was a strong believer in laissez-faire economics and disliked the proposals. (62) MacDonald had doubts about Snowden's "hard dogmatism exposed in words and tones as hard as the ideas" but he also dismissed "all the humbug of curing unemployment by Exchequer grants." (63) MacDonald passed the Mosley Memorandum to a committee consisting of Snowden, Tom Shaw, Arthur Greenwood and Margaret Bondfield. The committee reported back on 1st May. Mosley's administrative proposals, the committee claimed "cut at the root of the individual responsibilities of Ministers, the special responsibility of the Chancellor of the Exchequer in the sphere of finance, and the collective responsibility of the Cabinet to Parliament". The Snowden Report went onto argue that state action to reduce unemployment was highly dangerous. To go further than current government policy "would be to plunge the country into ruin". (64)

MacDonald recorded in his diary what happened when Mosley heard the news about his proposals being rejected. "Mosley came to see me... had to see me urgently: informed me he was to resign. I reasoned with him and got him to hold his decision over till we had further conversations. Went down to Cabinet Room late for meeting. Soon in difficulties. Mosley would get away from practical work into speculative experiments. Very bad impression. Thomas light, inconsistent but pushful and resourceful; others overwhelmed and Mosley on the verge of being offensively vain in himself." (65)

Oswald Mosley was not trusted by most of his fellow MPs. One Labour Party MP, Clement Attlee, said Mosley had a habit of speaking to his colleagues "as though he were a feudal landlord abusing tenants who are in arrears with their rent". (66) John Bew described Mosley as "handsome... lithe and black and shiny... he looked like a panther but behaved like a hyena". (67)

At a meeting of Labour MPs took place on 21st May, Oswald Mosley outlined his proposals. This included the provision of old-age pensions at sixty, the raising of the school-leaving age and an expansion in the road programme. He gained support from George Lansbury and Tom Johnson, but Arthur Henderson, speaking on behalf of MacDonald, appealed to Mosley to withdraw his motion so that his proposals could be discussed in detail at later meetings. Mosley insisted on putting his motion to the vote and was beaten by 210 to 29. (68)

Mosley now resigned from the government and was replaced by Clement Attlee. It has been claimed that MacDonald was so fed up with Mosley that he looked around him and choose the "most uninteresting, unimaginative but most reliable among his backbenchers to replace the fallen angel". Winston Churchill said Attlee was "a modest little man, with plenty to be modest about". Mosley was more generous as he accepted that he had "a clear, incisive and honest mind within the limits of his range". However, he added, in agreeing to take his job, Attlee "must be reckoned as content to join a government visibly breaking the pledges on which he was elected." (69)

The New Party

It was now clear that while Ramsay MacDonald was in power, Mosley's economic ideas would never be accepted. He therefore decided he had to have his own political party. In January 1931, Sir William Morris (later Lord Nuffield), a motor-car manufacturer, gave Mosley a cheque for £50,000 to form a new political party. Further donations came from the industrialist, Wyndham Portal, and tobacco millionaire Hugo Cunliffe-Owen. The left-wing Labour MP, Aneurin Bevan, who had supported the Mosley Memorandum, argued that if you accept funding from industrialists, "you will end up as a fascist party". (70)

On 20th February, 1931, Mosley and five Labour Party MPs, Cynthia Mosley, John Strachey, Robert Forgan, Oliver Baldwin (the son of Stanley Baldwin, the leader of the Conservative Party) and William J. Brown, decided to resign from the party. William E. Allen, the Tory MP for West Belfast, and Cecil Dudgeon, the Liberal MP for Galloway, also agreed to join the New Party. However, Brown and Baldwin changed their minds and sat in the House of Commons as Independents and six months later rejoined the Labour Party. (71).

Other people who joined the New Party included Cyril Joad (Director of Propaganda), Harold Nicholson (editor of their journal, Action), Mary Richardson (former member of the Women's Social and Political Union), John Becket and Peter Dunsmore Howard (captain of the England national rugby union team). The New Party's first electoral contest was at Ashton-under-Lyne after the death of Albert Bellamy, the Labour MP. The candidate was Allan Young, and his election agent was Wilfred Risdon. At the by-election on 30th April, 1931, Young split the Labour vote and the Conservative candidate, John Broadbent, was elected. (72)

At a committee meeting of the New Party on 14th May 1931, Oswald Mosley urged the formation of a group young men to provide protection at political meetings from other political groups. "The Communist Party will develop a challenge in this country which will seriously alarm people here. You will in effect have the situation which arose in Italy and other countries and which summoned into existence the modern movement which now rules in those countries. We have to build and create the skeleton of an organisation so as to meet it when the time comes." (73)

These comments disturbed those on the left of the party such as John Strachey and Cyril Joad, who disliked the comparisons with the Sturmabteilung (SA) used by the Nazi Party in Germany. This information was leaked to the press and he was forced to deny the comparisons with Adolf Hitler: "We are simply organising an active force of our young men supporters to act as stewards. The only methods we shall employ will be English ones. We shall rely on the good old English fist." (74)

Cynthia Mosley also disagreed with her husband's move to the right. According to Robert Skidelsky: "Cimmie (Cynthia) was frankly terrified of where his restlessness would lead him. She hated fascism and Harmsworth (Lord Rothermere, the press baron). She threatened to put a notice in The Times dissociating herself from Mosley's fascist tendencies. They bickered constantly in public, Cimmie emotional and confused, Mosley ponderously logical and heavily sarcastic." (75)

Harold Nicholson also was worried by Mosley's attraction to fascism. "What makes it so distressing is that I should like to be able to encourage and support you in everything you do and feel.... I do not think that in practice you will succeed in keeping distinct the ideology of fascism from the violent and untruthful methods which the fascists have adopted in Italy. I think there may well be a future for the corporate state idea in this country. But I do not think... there is any possible future for direct action: we have, by training and temperament, become possessed of indirect minds." (76)

John Strachey believed that the New Party should develop close contacts with the Soviet Union: "A New Party Government will enter into close economic relations with the Russian Government and will endeavour to conclude such trading contracts between suitable British and Russian statutory organisations as will rapidly develop the controlled interchange of goods between the two countries." When this policy was rejected, Strachey resigned from the party. (77)

In the 1931 General Election the New Party fielded 25 candidates. Mosley obtained 10,500 votes in Stoke-on-Trent but was bottom of the poll. Only two candidates, Mosley and Sellick Davies, standing in Merthyr Tydfil, saved their deposits. The total votes cast for the New Party were 36,377. This compared badly with the Communist Party of Great Britain, which managed 74,824 votes for 26 candidates. Ramsay MacDonald, and his National Government won 556 seats. Mosley told Nicolson that "we have been swept away in a hurricane of sentiment" and that "our time is yet to come". (78)

The British Union of Fascists

In January 1932, Oswald Mosley, William E. Allen and Harold Nicholson visited Italy to study fascism at first hand. Mosley met Benito Mussolini who he found "affable but unimpressive". Mussolini advised Mosley to "call himself a fascist, but not to try the military stunt in England". Nicholson claimed in his diary that Mosley was not put off by the way Mussolini had arrested his opponents and the censorship of Italian newspapers. "Mosley... cannot keep his mind off shock troops, the arrest of MacDonald and J. H. Thomas, their internment in the Isle of Wight and the roll of drums around Westminster. He is a romantic. That is a great failing." (79)

On his return to England, Mosley wrote an article in The Daily Mail about the achievements of Mussolini. "A visit to Mussolini... is typical of that new atmosphere. No time is wasted in the polite banalities which have so irked the younger generation in Britain when dealing with our elder statesmen.... Questions on all relevant and practical subjects are fired with the rapidity and precision of bullets from a machine gun; straight, lucid, unaffected exposition follows of his own views on subjects of mutual interest to him and to his visitor.... The great Italian represents the first emergence of the modern man to power; it is an interesting and instructive phenomenon. Englishmen who have long suffered from statesmanship in skirts can pay him no less, and need pay him no more, tribute than to say, Here at least is a man". (80)

Mosley now became convinced that the time was right to establish a fascist party. There had been fascist groups in the past. Miss Rotha Lintorn-Orman established the British Fascisti organization in 1923. She later said: "I saw the need for an organization of disinterested patriots, composed of all classes and all Christian creeds, who would be ready to serve their country in any emergency." Members of the British Fascists had been horrified by the Russian Revolution. However, they had gained inspiration from what Mussolini had done it Italy. (81)

Most members of the British Fascisti came from the right-wing of the Conservative Party. Early recruits included William Joyce, Maxwell Knight and Nesta Webster. Knight's work as Director of Intelligence for the British Fascists brought him to the attention of Vernon Kell, Director of the Home Section of the Secret Service Bureau. This government organization had responsibility of investigating espionage, sabotage and subversion in Britain and was also known as MI5. In 1925 Kell recruited Knight to work for the Secret Service Bureau and played a significant role in helping to defeat the General Strike in 1926. (82)

Arnold Leese, a retired veterinary surgeon, had founded the Imperial Fascist League (IFL) in 1929. He had a private army called the Fascist Legions, who never numbered more than three dozen, wore black shirts and breeches. The IFL defined fascism as the "patriotic revolt against democracy and a return to statesmanship" and planned to "impose a corporate state" on the country. It also believed that Jews should be banned from citizenship. The IFL enemies were Communism, Freemasonry and Jews. (83)

Mosley originally dismissed the Imperial Fascist League as "one of those crank little societies mad about the Jews". However, on 27th April 1932, Mosley arranged for Leese to speak to New Party members, on the subject of The Blindness of British Politics under Jew Money-Power. However, the two men did not get on well together. Leese refused all co-operation with Mosley, "believing him to be in the pay of the Jews". (84)

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was formally launched on 1st October, 1932. It originally had only 32 members and included several former members of the New Party: Cynthia Mosley, Robert Forgan, William E. Allen, John Beckett and William Joyce. Mosley told them: "We ask those who join us... to be prepared to sacrifice all, but to do so for no small or unworthy ends. We ask them to dedicate their lives to building in the country a movement of the modern age... In return we can only offer them the deep belief that they are fighting that a great land may live." (85)

Over the next few months a large number of people joined the organisation such as Charles Bentinck Budd, Harold Harmsworth (Lord Rothermere), Major General John Fuller, Wing-Commander Louis Greig, A. K. Chesterton, David Bertram Ogilvy Freeman-Mitford (Lord Redesdale), Unity Mitford, Diana Mitford, Patrick Boyle (8th Earl of Glasgow), Malcolm Campbell and Tommy Moran. Mosley refused to publish the names or numbers of members but the press estimated a maximum number of 35,000. (86)

Mosley decided that members of the BUF should wear a uniform. The black shirt was to be the symbol of fascism. According to Mosley the "black shirt was the outward and visible sign of an inward and spiritual grace". The uniform enabled his stewards to recognise each other in a fight against those trying to disrupt BUF meetings. "In addition, the uniform was a symbol of authority, and as such his uniformed squads would not only be a rallying-point, but also a striking-force in any battle that might develop with the communists for the control of the State." (87)

Mary Richardson was one of those who liked the idea of a uniform: "I was first attracted to the Blackshirts because I saw in them the courage, the action, the loyalty, the gift of service, and the ability to serve which I had known in the suffrage movement". Mosley commented: "In the Blackshirt all men are the same, whether millionaire or on the dole. The barriers of class distinction and social differences are broken down by the Blackshirt within a Movement which aims at the creation of a classroom brotherhood marked only by functional differences." (88)

Mosley began to argue for national socialism: "How can any international system, whether capitalist or Socialist, advance or even maintain the standard of life of our people? None can deny the truism that to sell we must find customers and, as foreign markets progressively close... the home customer becomes ever more the outlet of industry. But the home customer is simply the British people, on whose purchasing power our industry is ever more dependent. For the most part the purchasing power of the British people depends on the wages and salaries they are paid... Yet wages and salaries of the British people are held down far below the level which modern science, and the potential of production, could justify because their labour is subject to... undercutting competition... on both foreign and home markets.... The result is the tragic paradox of poverty and unemployment amid potential plenty.... Internationalism, in fact, robs the British people of the power to buy the goods that the British people produce." (89)

Cynthia Mosley remained a member of the British Union of Fascists but was not a strong believer in fascism. She was also in bad health. Harold Nicholson wrote: "Cimmie (Cynthia) comes to see me. She has not been well. She faints. She even faints in bed. She talks about Tom (Oswald) and Fascismo. She really does care for the working-classes and loathes all forms of reaction." (90)

Cynthia, the mother of two children (Elisabeth and Nicholas), had a difficult pregnancy with a third child. Nicholson once again wrote about the situation: "Cimmie has been very ill. She has kidney trouble and they want to do a caesarean operation. Unfortunately the child is too young to survive and Climmie wants to hang on for a fortnight. Tom (Oswald) is faced with the awful dilemma of sacrificing his baby or his wife." (91)

Michael Mosley was born on 25th April 1932. After a long convalescence Cynthia's health gradually recovered. In April 1933 she agreed to accompany her husband to visit Benito Mussolini. They all appeared together on the balcony of the Palazzo Venezia, and made the fascist salute in one of the very rare occasions when she publicly showed any sympathy with fascism." (92).

On her return to London she was again taken ill and was rushed to hospital to have her appendix removed. The operation was successful but two days later, on 16th May, 1933, she died of peritonitis. Oswald Mosley was completely shattered by Cynthia's death but according to his friends it intensified his political beliefs and made him even more committed to fascism: "He now regards his movement as a memorial to Cimmie and is prepared willingly to die for it." (93)

In a speech made in March, 1933, Mosley outlined his fascist beliefs: "The Fascist principle is private freedom and public service. That imposes upon us, in our public life, and in our attitude towards other men, a certain discipline and a certain restraint; but in our public life alone; and I should argue very strongly indeed that the only way to have private freedom was by a public organisation which brought some order out of the economic chaos which exists in the world today, and that such public organisation can only be secured by the methods of authority and of discipline which are inherent in Fascism." (94)

Mosley began to openly question democracy. He quoted approvingly the words of George Bernard Shaw: "What is the historical function of Parliament in this country? It is to prevent the Government from governing. It has never had any other purpose... Bit by bit it broke the feudal Monarchy; it broke the Church; and finally it even broke the country gentleman. Then, having broken everything that could govern the country, it left us at the mercy of our private commercial capitalists and landowners. Since then we have been governed from outside Parliament, first by our own employers, and of late by the financiers of all nations and races." (95)

Mosley believed the House of Commons tamed those who wished to change society: "Many a good revolutionary has arrived at Westminster roaring like a lion, only a few months later to be cooing as the tame dove of his opponent. The bar, the smoking room, the lobby, the dinner tables of his constituents' enemies, and the atmosphere of the best club in the country, very quickly rob a people's champion of his vitality and fighting power. Revolutionary movements lose their revolutionary ardour as a result long before they ever reach power, and the warrior of the platform becomes the lap-dog of the lobbies." (96)

Mosley suggested this problem could be dealt with by the introduction of the Corporate State. The government would preside over corporations formed from the employers, trade unions and consumer interests. Within the guidelines of a national plan, these corporations would work out its own policy for wages, prices, conditions of employment, investment and terms of competition. Government would intervene only to settle deadlocks between unions and employers. Strikes would be made illegal.

Mosley's critics on the left argued that his Corporate State would enshrine the freedom of capitalists to exploit a working-class deprived of both its industrial and political weapons. Mosley believed that working-class political parties and unions would not be needed: "In such a system (the Corporate State) there is no place for parties and for politicians. We shall ask the people for a mandate to bring an end the Party system and the Parties. We invite them to enter a new civilisation. Parties and the party game belong to the old civilisation, which has failed." (97)

The January Club

The January Club was a product of the dinners and functions held by Robert Forgan, a member of the British Union of Fascists (BUF) during the autumn of 1933. The chairman of the January Club was Sir John Collings Squire, who claimed that membership was open to anyone who was "in sympathy with the the Fascist movement". Squire's biographer, Patrick J. Howarth, claimed that "They believed that the present democratic system of government in this country must be changed, and although the change was unlikely to come about suddenly, as it had in Italy and Germany, they regarded it as inevitable." (98) The secretary of the January Club was Captain H. W. Luttman-Johnson and it has been argued that "the correspondence between Luttman-Johnson and Mosley leaves no doubt that the January Club was designed as a front organization for the BUF". (99)

The January Club stated that its objectives included: "(i) To bring together men who are interested in modern methods of government. (ii) To provide a platform for leaders of Fascist and Corporate State thought. The club, however, will not formulate any policy of its own. (iii) To enable those who are propagating Fascism to hear the views of those who, while sympathizing with and students of twentieth-century political thought, are not themselves Fascists." (100)

The journalist and novelist, Cecil Roberts, attended one of their first meetings with his friend, Francis Yeats-Brown. He later recalled: The majority appeared to be tentative enquirers like myself. Some of the speeches struck a note of accord in their deprecation of the lassitude of our Government. On invitation I spoke myself, expressing all my pent-up indignation and alarm. Sir John Squire, who was present, an enquirer like myself, repeatedly congratulated me on that speech." (101)

Members of the January Club included Basil Liddell Hart, General Sir Hubert Gough, Wing-Commander Sir Louis Greig, Gentleman Usher to the King George VI, Sir Henry Fairfax-Lucy, Sir Philip Magnus-Allcroft MP, Sir Thomas Moore and Ralph Blumenfeld, the editor of the Daily Express. (102) Speakers at the meetings included Mary Allen, the commander of the Women's Police Service since 1920, William Joyce, Muriel Innes Currey, Alexander Raven Thomson and Air Commodore John Adrian Chamier. (103) Richard C. Thurlow has pointed out that the January Club, was part of the "considerable hidden history of British fascism." (104)

The most important member of the January Club was the newspaper baron, Harold Harmsworth, the 1st Lord Rothermere. According to S. J. Taylor, the author of The Great Outsiders: Northcliffe, Rothermere and the Daily Mail (1996), as early as 1931, Rothermere was offering to place "the whole of the Harmsworth press at Mosley's disposal". Rothermere believed that Mosley and his fledgling Fascists represented "sound, commonplace, Conservative doctrine". Inspired by "loyalty to the throne and love of country", they were little more than an energetic wing of the Conservative Party". (105)

Stephen Dorril has explained that the men who established the January Club later admitted that its main objective was to provide a platform for Oswald Mosley and the British Union of Fascists (BUF). (106) "At a conference in the Home Office in November 1933 attended by the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, two officers of MI5 and a superintendent from Special Branch, it was decided that information should be systematically collected on fascism in the United Kingdom." (107) These reports from MI5 pointed out that the January Club was "a powerhouse for the development of Fascist culture" and "it brought fascism to the notice of large numbers of people who would have considered it much less favourably otherwise." (108)

After the 1933 General Election, Chancellor Adolf Hitler proposed an Enabling Bill that would give him dictatorial powers. Such an act needed three-quarters of the members of the Reichstag to vote in its favour. All the active members of the Communist Party, were in prison, in hiding, or had left the country (an estimated 60,000 people left Germany during the first few weeks after the election). This was also true of most of the leaders of the other left-wing party, Social Democrat Party (SDP). However, Hitler still needed the support of the Catholic Centre Party (BVP) to pass this legislation. Hitler therefore offered the BVP a deal: vote for the bill and the Nazi government would guarantee the rights of the Catholic Church. The BVP agreed and when the vote was taken on 24th March, 1933, only 94 members of the SDP voted against the Enabling Bill. (109)

Soon afterwards the Communist Party and the Social Democrat Party became banned organisations. Party activists still in the country were arrested. A month later Hitler announced that the Catholic Centre Party, the Nationalist Party and all other political parties other than the NSDAP were illegal, and by the end of 1933 over 150,000 political prisoners were in concentration camps. Hitler was aware that people have a great fear of the unknown, and if prisoners were released, they were warned that if they told anyone of their experiences they would be sent back to the camp. (110)

Lord Rothermere produced a series of articles acclaiming the new regime. The most famous of these was on the 10th July when he told readers that he "confidently expected" great things of the Nazi regime. He also criticized other newspapers for "its obsession with Nazi violence and racialism", and assured his readers that any such deeds would be "submerged by the immense benefits that the new regime is already bestowing on Germany." He pointed out that those criticizing Hitler were on the left of the political spectrum. (111)

Hitler acknowledged this help by writing to Rothermere: "I should like to express the appreciation of countless Germans, who regard me as their spokesman, for the wise and beneficial public support which you have given to a policy that we all hope will contribute to the enduring pacification of Europe. Just as we are fanatically determined to defend ourselves against attack, so do we reject the idea of taking the initiative in bringing about a war. I am convinced that no one who fought in the front trenches during the world war, no matter in what European country, desires another conflict." (112) In another article Lord Rothermere called for Hitler to be given back land in Africa that had been taken as a result of the Versailles Treaty. (113)

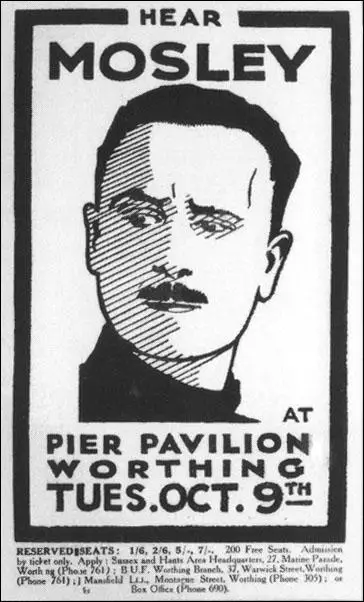

Success in Worthing

At an election meeting in Broadwater on 16th October 1933, Charles Bentinck Budd revealed he had recently met Sir Oswald Mosley and had been convinced by his political arguments and was now a member of the British Union of Fascists (BUF). Budd added that if he was elected to the local council "you will probably see me walking about in a black shirt". (114)

Budd won the contest and the national press reported that Worthing was the first town in the country to elect a Fascist councillor. Worthing was now described as the "Munich of the South". A few days later Mosley announced that Budd was the BUF Administration Officer for Sussex. Budd also caused uproar by wearing his black shirt to council meetings. (115)

On Friday 1st December 1933, the BUF held its first public meeting in Worthing in the Old Town Hall. According to one source: "It was crowded to capacity, with the several rows of seats normally reserved for municipal dignitaries and magistrates now occupied by forbidding, youthful men arrived in black Fascist uniforms, in company with several equally young women dressed in black blouses and grey skirts." (116)

Budd reported that over 150 people in Worthing had joined the British Union of Fascists. Some of the new members were former communists but the greatest intake had come from increasingly disaffected Conservatives. The Weekly Fascist News described the growth in membership as "phenomenal" as a few months ago members could be counted on one's fingers, and now "hundreds of young men and women -.together with the many leading citizens of the town - now participated in its activities". (117)

The mayor of Worthing, Harry Duffield, the leader of the Conservative Party in the town, was most favourably impressed with the Blackshirts and congratulated them on the disciplined way they had marched through the streets of Worthing. He reported that employers in the town had written to him giving their support for the British Union of Fascists. They had "no objection to their employees wearing the black shirt even at work; and such public spirited action on their part was much appreciated." (118)

The Daily Mail and the British Union of Facists

Harold Harmsworth, Lord Rothermere, the press baron, was a great supporter of Adolf Hitler. According to James Pool, the author of Who Financed Hitler: The Secret Funding of Hitler's Rise to Power (1979): "Shortly after the Nazis' sweeping victory in the election of September 14, 1930, Rothermere went to Munich to have a long talk with Hitler, and ten days after the election wrote an article discussing the significance of the National Socialists' triumph. The article drew attention throughout England and the Continent because it urged acceptance of the Nazis as a bulwark against Communism... Rothermere continued to say that if it were not for the Nazis, the Communists might have gained the majority in the Reichstag." (119)

Louis P. Lochner, the author of Tycoons and Tyrant: German Industry from Hitler to Adenauer (1954) Lord Rothermere provided funds to Hitler via Ernst Hanfstaengel. When Hitler became Chancellor on 30th January 1933, Rothermere produced a series of articles acclaiming the new regime. "I urge all British young men and women to study closely the progress of the Nazi regime in Germany. They must not be misled by the misrepresentations of its opponents. The most spiteful distracters of the Nazis are to be found in precisely the same sections of the British public and press as are most vehement in their praises of the Soviet regime in Russia." (120)

George Ward Price, the Daily Mail's foreign correspondent developed a very close relationship with Adolf Hitler. According to the German historian, Hans-Adolf Jacobsen: "The famous special correspondent of the London Daily Mail, Ward Price, was welcomed to interviews in the Reich Chancellery in a more privileged way than all other foreign journalists, particularly when foreign countries had once more been brusqued by a decision of German foreign policy. His paper supported Hitler more strongly and more constantly than any other newspaper outside Germany." (121)

Franklin Reid Gannon, the author of The British Press and Germany (1971), has claimed that Hitler regarded him as "the only foreign journalist who reported him without prejudice". (122) In his autobiography, Extra-Special Correspondent (1957), Ward Price defended himself against the charge he was a fascist by claiming: "I reported Hitler's statements accurately, leaving British newspaper readers to form their own opinions of their worth." (123)

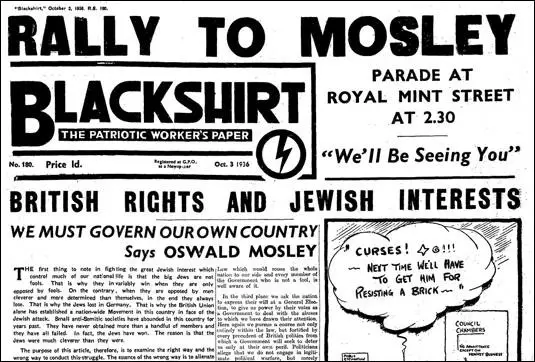

Lord Rothermere also gave full support to Oswald Mosley and the National Union of Fascists. He wrote an article, Hurrah for the Blackshirts, on 22nd January, 1934, in which he praised Mosley for his "sound, commonsense, Conservative doctrine". Rothermere added: "Timid alarmists all this week have been whimpering that the rapid growth in numbers of the British Blackshirts is preparing the way for a system of rulership by means of steel whips and concentration camps. Very few of these panic-mongers have any personal knowledge of the countries that are already under Blackshirt government. The notion that a permanent reign of terror exists there has been evolved entirely from their own morbid imaginations, fed by sensational propaganda from opponents of the party now in power. As a purely British organization, the Blackshirts will respect those principles of tolerance which are traditional in British politics. They have no prejudice either of class or race. Their recruits are drawn from all social grades and every political party. Young men may join the British Union of Fascists by writing to the Headquarters, King's Road, Chelsea, London, S.W." (124)

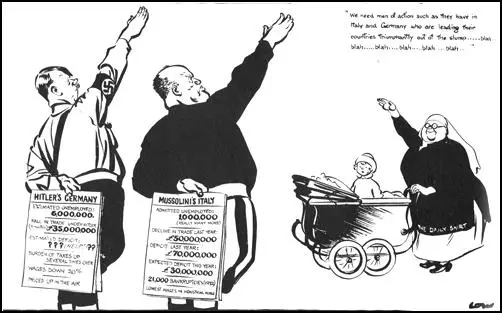

David Low, a cartoonist employed by the Evening Standard, made several attacks on Rothermere's links to the fascist movement. In January 1934, he drew a cartoon showing Rothermere as a nanny giving a Nazi salute and saying "we need men of action such as they have in Italy and Germany who are leading their countries triumphantly out of the slump... blah... blah... blah... blah." The child in the pram is saying "But what have they got in their other hands, nanny?" Hitler and Mussolini are hiding the true records of their periods in government. Hitler's card includes, "Hitler's Germany: Estimated Unemployed: 6,000,000. Fall in trade under Hitler (9 months) £35,000,000. Burden of taxes up several times over. Wages down 20%." (125)

Lord Beaverbrook, the owner of the Evening Standard, was a close friend and business partner of Lord Rothermere, and refused to allow the original cartoon to be published. At the time, Rothermere controlled forty-nine per cent of the shares. Low was told by one of Beaverbrook's men: "Dog doesn't eat dog. It isn't done." Low commented that it was said as "though he were giving me a moral adage instead of a thieves' wisecrack." He was forced to make the nanny unrecgnisable as Rothermere and had to change the name on her dress from the Daily Mail to the Daily Shirt. (126)

The Daily Mail continued to give its support to the fascists. Lord Rothermere allowed fellow member of the January Club, Sir Thomas Moore, the Conservative Party MP for Ayr Burghs, to publish pro-fascist articles in his newspaper. Moore described the BUF as being "largely derived from the Conservative Party". He added "surely there cannot be any fundamental difference of outlook between the Blackshirts and their parents, the Conservatives?" (127)

In April 1934, The Daily Mail published an article by Randolph Churchill that praised a speech that Mosley made in Leeds: "Sir Oswald's peroration was one of the most magnificent feats of oratory I have ever heard. The audience which had listened with close attention to his reasoned arguments were swept away in spontaneous reiterated bursts of applause." (128)

Violence and the British Union of Fascists

The London Evening News, another newspaper owned by Lord Rothermere, found a more popular and subtle way of supporting the Blackshirts. It obtained 500 seats for a BUF rally at the Royal Albert Hall and offered them as prizes to readers who sent in the most convincing reasons why they liked the Blackshirts. Rothermere's , The Sunday Dispatch, even sponsored a Blackshirt beauty competition to find the most attractive BUF supporter. Not enough attractive women entered and the contest was declared void. (129)

David Low was one of those who attended the meeting at the Royal Albert Hall: "Mosley spoke effectively at great length. Delivery excellent, matter reckless. Interruptions began, but no dissenting voice got beyond half a dozen sentences before three or four bullies almost literally jumped on him, bashed him and lugged him out. Two such incidents happened near me. An honest looking blue-eyed student type rose and shouted indignantly 'Hitler means war!' whereupon he was given the complete treatment." (130)

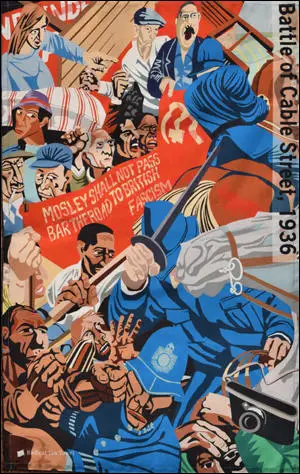

Oswald Mosley decided to hold a large British Union of Fascists rally at Olympia on 7th June. Soon after the meeting was announced, The Daily Worker issued a statement declaring that the Communist Party of Great Britain intended to demonstrate against Mosley by organized heckling inside the meeting and by a mass demonstration outside the hall. (131)

The CPGB did what it could to disrupt the meeting. As Robert Benewick, the author of The Fascist Movement in Britain (1972) pointed out: "They (the CPGB) printed illegal tickets. Groups of hecklers were stationed at strategic points inside the meeting, and Press interviews with their members were organized outside. First-aid stations were set up in near-by houses, and there were the inevitable parades, banners, placards and slogans. It was unlikely that weapons were officially authorized but this would not have prevented anyone from carrying them." (132) In fact, Philip Toynbee later admitted that he and Esmond Romilly both took knuckle-dusters to the meeting. (133)

About 500 anti-fascists including Vera Brittain, Richard Sheppard and Aldous Huxley, managed to get inside the hall. When they began heckling Oswald Mosley they were attacked by 1,000 black-shirted stewards. Several of the protesters were badly beaten by the fascists. Margaret Storm Jameson pointed out in The Daily Telegraph: "A young woman carried past me by five Blackshirts, her clothes half torn off and her mouth and nose closed by the large hand of one; her head was forced back by the pressure and she must have been in considerable pain. I mention her especially since I have seen a reference to the delicacy with which women interrupters were left to women Blackshirts. This is merely untrue... Why train decent young men to indulge in such peculiarly nasty brutality?" (134)

Collin Brooks, was a journalist who worked for Lord Rothermere at the The Sunday Dispatch. He also attended the the rally at Olympia. Brooks wrote in his diary: "He (Mosley) mounted to the high platform and gave the salute - a figure so high and so remote in that huge place that he looked like a doll from Marks and Spencer's penny bazaar. He then began - and alas the speakers hadn't properly tuned in and every word was mangled. Not that it mattered - for then began the Roman circus. The first interrupter raised his voice to shout some interjection.The mob of storm troopers hurled itself at him. He was battered and biffed and hashed and dragged out - while the tentative sympathisers all about him, many of whom were rolled down and trodden on, grew sick and began to think of escape. From that moment it was a shambles. Free fights all over the show. The Fascist technique is really the most brutal thing I have ever seen, which is saving something. There is no pause to hear what the interrupter is saying: there is no tap on the shoulder and a request to leave quietly: there is only the mass assault. Once a man's arms are pinioned his face is common property to all adjacent punchers." Brooks also commented that one of his "party had gone there very sympathetic to the fascists and very anti-Red". As they left the meeting he said "My God, if ifs to be a choice between the Reds and these toughs, I'm all for the Reds". (135)

Several members of the Conservative Party were in the audience. Geoffrey Lloyd pointed out that Mosley stopped speaking at once for the most trivial interruptions, although he had a battery of twenty-four loud-speakers. The interrupters were then attacked by ten to twenty stewards. Mosley's claim that he was defending the right of freedom was "pure humbug" and his tactics were calculated to provide an "apparent excuse" for violence. (136) William Anstruther-Gray, the MP for North Lanark, agreed with Lloyd: "Frankly if anybody had told me an hour before the meeting at Olympia that I should find myself on the side of the Communist interrupters, I would have called him a liar." (137)

However, George Ward Price, of The Daily Mail disagreed and put all the blame on the demonstrators: "If the Blackshirts movement had any need of justification, the Red Hooligans who savagely and systematically tried to wreck Sir Oswald Mosley's huge and magnificently successful meeting at Olympia last night would have supplied it. They got what they deserved. Olympia has been the scene of many assemblies and many great fights, but never had it offered the spectacle of so many fights mixed up with a meeting." (138)

In the debate that took place in the House of Commons on the BUF rally, several Tory MPs defended Mosley. Michael Beaumont by admitting that he was an "anti-democrat and an avowed admirer of Fascism in other countries" and from what he observed inside the meeting, no one there "got anything more than he deserved". (139) Tom Howard, the MP for Islington South, admired Mosley for his determination to maintain the right of free speech. He was also worried that the BUF were taking members from the Tories: "The tens of thousands of young men who had joined the Blackshirts... are the best element of the country". (140)

Clement Attlee, the Deputy Leader of the Labour Party, claimed to have evidence to demonstrate that the Blackshirts used "plain-clothes inciters to disorder" at their meetings and that the Blackshirts used deliberate incitement as an excuse for force. (141) Walter Citrine, the General Secretary of the Trade Union Congress, demanded an end to "the drilling and arming of civilian sections of the community" and deplored the inactivity of the police and the courts in dealing with the British Union of Fascists." (142)

Stanley Baldwin, the prime minister, admitted that there were similarities between the Conservative Party and the British Union of Fascists but because of its "ultramontane Conservatism... it takes many of the tenets of our own party and pushes them to a conclusion which, if given effect to, would, I believe, be disastrous to our country." (143) The government rejected a proposal for a public inquiry into the violence at the Olympia meeting but the Home Secretary gave several hints on the possibility of legislation that would help prevent trouble at political meetings. (144)

In July, 1934 Lord Rothermere suddenly withdrew his support for Oswald Mosley. The historian, James Pool, the author of Who Financed Hitler: The Secret Funding of Hitler's Rise to Power (1979), argues: "The rumor on Fleet Street was that the Daily Mail's Jewish advertisers had threatened to place their adds in a different paper if Rothermere continued the pro-fascist campaign." Pool points out that sometime after this, Rothermere met with Hitler at the Berghof and told how the "Jews cut off his complete revenue from advertising" and compelled him to "toe the line." Hitler later recalled Rothermere telling him that it was "quite impossible at short notice to take any effective counter-measures." (145)

Vernon Kell, of MI5, reported to the Home Office that the rally at Olympia appeared to have had a negative impact on the future of the National Union of Fascists: "It is becoming increasingly clear that at Olympia Mosley suffered a check which is likely to prove decisive. He suffered it, not at the hands of the Communists who staged the provocations and now claim the victory; but at the hands of Conservative MPs, the Conservative press and all those organs of public opinion which made him abandon the policy of using his Defence Force to overwhelm interrupters." (146)

Oswald Mosley had developed a large following in Sussex after the election of Charles Bentinck Budd, the fascists only councillor. Budd arranged for Mosley and William Joyce to address a meeting at the Worthing Pavilion Theatre on 9th October, 1934. The British Union of Fascists covered the town with posters with the words "Mosley Speaks", but during the night someone had altered the posters to read "Gasbag Mosley Speaks Tripe". It was later discovered that this had been done by Roy Nicholls, the chairman of the Young Socialists. (147)

The venue was packed with fascist supporters from Sussex. According to Michael Payne: "Finally the curtain rose to reveal Sir Oswald himself standing alone on the stage. Clad entirely in black, the great silver belt buckle gleaming, the right arm raised in the Fascist salute, he was spell-bindingly illuminated in the hushed, almost reverential atmosphere by the glare of spotlights from right, left and centre. A forest of black-sleeved arms immediately shot up to hail him." (148)

The meeting was disrupted when a few hecklers were ejected by hefty East End bouncers. Mosley, however, continued his speech undaunted, telling his audience that Britain's enemies would have to be deported: "We were assaulted by the vilest mob you ever saw in the streets of London - little East End Jews, straight from Poland. Are you really going to blame us for throwing them out?" (149)

At the close of proceedings Mosley and Joyce, accompanied by a large body of blackshirts, marched along the Esplanade.They were protected by all nineteen available members of the Borough's police force. The crowd of protesters, estimated as around 2,000 people, attempted to block their path. A ninety-six-year-old woman, Doreen Hodgkins, was struck on the head by a Blackshirt before being escorted away. When the Blackshirts retreated inside, the crowd began to chant: "Poor old Mosley's got the wind up!" (150)