On this day on 27th April

On this day in 1667 blind and impoverished, John Milton sells Paradise Lost to a printer for £10. Milton, the son of a stockbroker, was born in London in 1608. He was educated at St. Paul's School and Christ's College, Cambridge and while at university began writing poetry in Latin, Italian and English. Over the next few years his fame grew with works such as Ode Upon the Morning of Christ's Nativity (1629), On Shakespeare (1632), Lycidas (1637) and Epitaphium Damonis (1639).

Milton was touring Italy when he heard about the conflict between Charles I and Parliament. Milton, a Puritan, returned to England to support the rebels. This included the publication of several pamphlets attacking the Anglican Church such as Of Reformation (1641), Of Prelatical Episcopacy (1641), The Reason of Church Government (1642) and Apology for Smectymnuus (1642).

In 1642 Milton married Mary Powell. However, after six weeks, upset by his political views, she returned to her Royalist family. This resulted in him publishing The Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce (1643), where he argued that an incompatibility of mind and spirit was a better ground for divorce than adultery. This was followed by On Education (1644) and Areopagitica, A Speech for the Liberty of Unlicensed Printing (1644), a passionate argument for a free press.

Milton's wife returned in 1645 and the couple had four children: Anne (1646), Mary (1648), John (1651) and Deborah (1652). Soon after the birth of Deborah, Milton's wife and son John died.

Milton, a staunch republican, supported the trial and execution of Charles I and in 1649 published The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates. During the Commonwealth Milton was Latin Secretary to the Council of State. His assistant was his close friend, Andrew Marvell. Marvell's help became even more important after Milton lost his sight in 1651. He continued to write and published several pamphlets including Pro Populo Anglicano Defensio (1651), Defensio Secunda (1654) and Defensio Pro Populo Anglicano (1655).

John Milton also wrote poems praising Oliver Cromwell, Thomas Fairfax and Henry Vane. However, Milton grew increasingly concerned about the authoritarianism of Cromwell's government. On Cromwell's death Milton published The Ready and Easy Way to Establish a Free Commonwealth.

After the Restoration Milton's work was burnt in public. Milton went briefly into hiding fearing he would be executed as a Regicide. Over the next few years he devoted himself to writing and during this period published Paradise Lost (1667), The History of Britain (1670), Paradise Regained (1671), Samson Agonistes (1671) and Of True Religion (1673). John Milton died on 8th November, 1674.

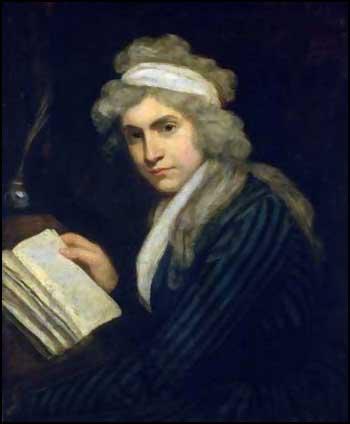

On this day in 1759 Mary Wollstonecraft, the eldest daughter of Edward Wollstonecraft and Elizabeth Dixon Wollstonecraft, was born in Spitalfields, London. At the time of her birth, Wollstonecraft's family was fairly prosperous: her paternal grandfather owned a successful Spitalfields silk weaving business and her mother's father was a wine merchant in Ireland.

Mary did not have a happy childhood. Claire Tomalin, the author of The Life and Death of Mary Wollstonecraft (1974) has pointed out: "Mary's father was sporadically affectionate, occasionally violent, more interested in sport than work, and not to be relied on for anything, least of all for loving attention. Her mother was indolent by nature and made a darling of her first-born, Ned, two years older than Mary; by the time the little girl had learned to walk in jealous pursuit of this loving pair, a third baby was on the way. A sense of grievance may have been her most important endowment."

In 1765 her grandfather died and her father, his only son, inherited a large share of the family business. He sold the business and purchased a farm at Epping. However, her father had no talent for farming. According to Mary, he was a bully, who abused his wife and children after heavy drinking sessions. She later recalled that she often had to intervene to protect her mother from her father's drunken violence William Godwin claims this had a major impact on the development of her personality as Mary "was not formed to be the contented and unresisting subject of a despot".

Mary had several younger brothers and sisters: Henry (1761), Eliza (1763), Everina (1765), James (1768) and Charles (1770). When she was nine years of age, the family moved to a farm in Beverley where Mary received a couple years at the local school, where she learned to read and write. It was the only formal schooling she was to receive. Ned, on the other hand, received a good education, with the hope that eventually he would become a lawyer. Mary was upset by the amount of attention Ned received and said of her mother "in comparison with her affection for him, she might be said not to love the rest of her children".

In 1673 Mary became friends with another fourteen-year-old, girl, Jane Arden. Her father, John Arden, was a highly educated man who gave public lectures on natural philosophy and literature. Arden also gave lessons to his daughter and her new friend. "Sensitive about the failings she was beginning to perceive in her own family, and contrasting them with the dignified, sober and well-read Ardens, Mary envied Jane her entire situation and attached herself determinedly to the family."

Mary and Jane had a argument and stopped seeing each other. However, they did keep in contact by letter: "Before I begin I beg pardon for the freedom of my style. If I did not love you I should not write so; I have a heart that scorns disguise, and a countenance which will not dissemble: I have formed romantic notions of friendship. I have been once disappointed - I think if I am a second time I shall only want some infidelity in a love affair, to qualify me for an old maid, as then I shall have no idea of either of them. I am a little singular in my thoughts of love and friendship; I must have the first place or none. - I own your behaviour is more according to the opinion of the world, but I would break such narrow bounds"

In 1774 Edward Wollstonecraft's financial situation forced the family to move again. This time they returned to a house in Hoxton. Her brother, Ned, was being trained as a lawyer, and used to come home at weekends. Mary continued to have a bad relationship with her brother and constantly undermined her confidence. She later recalled that he took "particular pleasure in tormenting and humbling me".

While in London she met Fanny Blood. "She was conducted to the door of a small house, but furnished with peculiar neatness and propriety. The first object that caught her sight, was a young woman of slender and elegant form... busily employed in feeding and managing some children, born of the same parents, but considerably her inferior in age. The impression Mary received from this spectacle was indelible; and before the interview was concluded, she had taken, in her heart, the vows of eternal friendship."

Mary identified closely with her new friend: "Fanny was eighteen to Mary's sixteen, slim and pretty and set apart from the rest of her family by her manners and talents. Mary could see in her a mirror-image of herself: an eldest daughter, superior to her surroundings, often in charge of a brood of little ones, with an improvident and a drunken father and a mother charming and gentle but quite broken in spirit."

After two years in London the family moved to Laugharne in Wales but Mary continued to correspond with Fanny, who had been promised in marriage to Hugh Skeys, who was living in Lisbon. Mary said in one letter that her feeling for her "resembled a passion" and was "almost (but not quite) that of an intending husband". Mary explained to Jane Arden that her relationship with Fanny was difficult to explain: "I know my resolution may appear a little extra-ordinary, but in forming it I follow the dictates of reason as well as the bent of my inclination."

Mary's mother died in 1782. She now went to live with Fanny Blood and her parents at Waltham Green. Her sister Eliza, married Meredith Bishop, a boat-builder from Bermondsey. In August, 1783, after the birth of her first child, she suffered a mental breakdown and Mary was asked to look after her. When she arrived at her sister's home Mary found Eliza in a very disturbed state. Eliza explained that she had "been very ill-used by her husband".

Mary Wollstonecraft wrote to her sister, Everina, explaining that "Bishop cannot behave properly - and those who attempt to reason with him must be mad or have very little observation... My heart is almost broken with listening to Bishop while he reasons the case. I cannot insult him with advice which he would never have wanted if he was capable of attending to it." In January, 1784, the two sisters escaped from Bishop and went to live under a false name in Hackney.

A few months later Mary Wollstonecraft opened a school in Newington Green, with her sister Eliza and a friend, Fanny Blood. Soon after arriving in the village, Mary made friends with Richard Price, a minister at the local Dissenting Chapel. Price and his friend, Joseph Priestley, were the leaders of a group of men known as Rational Dissenters. Price told her that the "love of God meant attacking injustice".

Price had written several books including the very influential Review of the Principal Questions of Morals (1758) where he argued that individual conscience and reason should be used when making moral choices. Price also rejected the traditional Christian ideas of original sin and eternal punishment. As a result of these religious views, some Anglicans accused Rational Dissenters of being atheists.

In January 1784, Fanny Blood travelled to Lisbon to marry Hugh Skeys. Mary missed her deeply and wrote that "without someone to love the world is a desert". She confessed that "my heart sometimes overflows with tenderness - and at other times seems quite exhausted and incapable of being warmly interested about anyone." She was attracted to John Hewlett, a young schoolmaster, and was very upset when he married another woman.

Fanny Blood became seriously ill and Mary decided to visit her in Portugal. When she arrived she discovered that Fanny was nine-months pregnant. She successfully gave birth but within days both Fanny and the child were dead. Mary stayed on in Lisbon for several weeks. She and Skeys were drawn together in their grief but she had to return to her school and returned to England in February 1786.

Wollstonecraft argued that friendship was more important than love: "Friendship is a serious affection; the most sublime of all affections, because it is founded on principle, and cemented by time. The very reverse may be said of love. In a great degree, love and friendship cannot subsist in the same bosom; even when inspired by different objects they weaken or destroy each other, and for the same object can only be felt in succession. The vain fears and fond jealousies, the winds which fan the flame of love, when judiciously or artfully tempered, are both incompatible with the tender confidence and sincere respect of friendship".

Although Mary was brought up as an Anglican, she soon began attending Price's Unitarian Chapel. Price held radical political views and had encountered a great deal of hostility when he supported the cause of American independence. At Price's home Mary Wollstonecraft met other leading radicals including the publisher, Joseph Johnson. He was impressed by Mary's ideas on education and commissioned her to write a book on the subject. In Thoughts on the Education of Girls, published in 1786, Mary attacked traditional teaching methods and suggested new topics that should be studied by girls.

Mary Wollstonecraft became emotionally involved with the artist Henry Fuseli. He had made a living from producing pornographic drawings and eventually gained fame for his painting The Nightmare, that showed a sleeping woman, head and shoulders dropped back over the end of her couch. She is surmounted by an incubus that peers out at the viewer. Contemporary critics were taken aback by the overt sexuality of the painting.

Fuseli was forty-seven and Mary twenty-nine. He was recently married to his former model, Sophia Rawlins. Fuseli shocked his friends by constantly talking about sex. Mary later told William Godwin that she never had a physical relationship with Fuseli but she did enjoy "the endearments of personal intercourse and a reciprocation of kindness, without departing in the smallest degree from the rules she prescribed to herself".

Mary fell deeply in love with Fuseli: "From him Mary learnt much about the seamy side of life... Obviously there was a time when they were in love with one another, and playing with fire; the increase of Mary's love to the point where it became torture to her is hard to explain if it remained at all times entirely platonic." Mary wrote that she was enraptured by his genius, "the grandeur of his soul, that quickness of comprehension, and lovely sympathy". She proposed a platonic living arrangement with Fuseli and his wife, but Sophia rejected the idea and he broke off the relationship with Wollstonecraft.

In 1788 Joseph Johnson and Thomas Christie established the Analytical Review. The journal provided a forum for radical political and religious ideas and was often highly critical of the British government. Mary Wollstonecraft wrote articles for the journal. So also did the scientist, Joseph Priestley, the philosopher, Erasmus Darwin, the poet William Cowper, the moralist William Enfield, the physician John Aikin, the author Anna Laetitia Barbauld; the Unitarian minister William Turner; the literary critic James Currie; the artist Henry Fuseli; the writer Mary Hays and the theologian Joshua Toulmin.

Mary and her radical friends welcomed the French Revolution. In November, 1789, Richard Price preached a sermon praising the revolution. Price argued that British people, like the French, had the right to remove a bad king from the throne. "I see the ardour for liberty catching and spreading; a general amendment beginning in human affairs; the dominion of kings changed for the dominion of laws, and the dominion of priest giving way to the dominion of reason and conscience."

Edmund Burke, was appalled by this sermon and wrote a reply called Reflections on the Revolution in France where he argued in favour of the inherited rights of the monarchy. He also attacked political activists such as Major John Cartwright, John Horne Tooke, John Thelwall, Granville Sharp, Josiah Wedgwood, Thomas Walker, who had formed the Society for Constitutional Information, an organisation that promoted the work of Tom Paine and other campaigners for parliamentary reform.

Burke attacked the dissenters who were wholly "unacquainted with the world in which they are so fond of meddling, and inexperienced in all its affairs, on which they pronounce with so much confidence". He warned reformers that they were in danger of being repressed if they continued to call for changes in the system: "We are resolved to keep an established church, an established monarchy, an established aristocracy, and an established democracy; each in the degree it exists, and in no greater."

Joseph Priestley was one of those attacked by Burke, pointed out: "If the principles that Mr Burke now advances (though it is by no means with perfect consistency) be admitted, mankind are always to be governed as they have been governed, without any inquiry into the nature, or origin, of their governments. The choice of the people is not to be considered, and though their happiness is awkwardly enough made by him the end of government; yet, having no choice, they are not to be the judges of what is for their good. On these principles, the church, or the state, once established, must for ever remain the same." Priestley went on to argue that these were the principles "of passive obedience and non-resistance peculiar to the Tories and the friends of arbitrary power."

Mary Wollstonecraft also felt that she had to respond to Burke's attack on her friends. Joseph Johnson agreed to publish the work and decided to have the sheets printed as she wrote. According to one source when "Mary had arrived at about the middle of her work, she was seized with a temporary fit of topor and indolence, and began to repent of her undertaking." However, after a meeting with Johnson "she immediately went home; and proceeded to the end of her work, with no other interruption but what were absolutely indispensable".

The pamphlet A Vindication of the Rights of Man not only defended her friends but also pointed out what she thought was wrong with society. This included the slave trade and way that the poor were treated. In one passage she wrote: "How many women thus waste life away the prey of discontent, who might have practised as physicians, regulated a farm, managed a shop, and stood erect, supported by their own industry, instead of hanging their heads surcharged with the dew of sensibility, that consumes the beauty to which it at first gave lustre."

The pamphlet was so popular that Johnson was able to bring out a second edition in January, 1791. Her work was compared to that of Tom Paine, the author of Common Sense. Johnson arranged for her to meet Paine and another radical writer, William Godwin. Henry Fuseli's friend, William Roscoe, visited her and he was so impressed by her that he commissioned a portrait of her by John Williamson. "She took the trouble to have her hair powdered and curled for the occasion - a most unrevolutionary gesture - but was not very pleased with the painter's work."

In 1791 Tom Paine published Rights of Man. In the book Paine attacked hereditary government and argued for equal political rights. Paine suggested that all men over twenty-one in Britain should be given the vote and this would result in a House of Commons willing to pass laws favourable to the majority. The book also recommended progressive taxation, family allowances, old age pensions, maternity grants and the abolition of the House of Lords. "The whole system of representation is now, in this country, only a convenient handle for despotism, they need not complain, for they are as well represented as a numerous class of hard-working mechanics, who pay for the support of royalty when they can scarcely stop their children's mouths with bread."

The book also recommended progressive taxation, family allowances, old age pensions, maternity grants and the abolition of the House of Lords. Paine also argued that a reformed Parliament would reduce the possibility of going to war. "Whatever is the cause of taxes to a Nation becomes also the means of revenue to a Government. Every war terminates with an addition of taxes, and consequently with an addition of revenue; and in any event of war, in the manner they are now commenced and concluded, the power and interest of Governments are increased. War, therefore, from its productiveness, as it easily furnishes the pretence of necessity for taxes and appointments to places and offices, becomes a principal part of the system of old Governments; and to establish any mode to abolish war, however advantageous it might be to Nations, would be to take from such Government the most lucrative of its branches. The frivolous matters upon which war is made show the disposition and avidity of Governments to uphold the system of war, and betray the motives upon which they act."

The British government was outraged by Paine's book and it was immediately banned. Paine was charged with seditious libel but he escaped to France before he could be arrested. Paine announced that he did not wish to make a profit from The Rights of Man and anyone had the right to reprint his book. It was printed in cheap editions so that it could achieve a working class readership. Although the book was banned, during the next two years over 200,000 people in Britain managed to buy a copy.

Mary Wollstonecraft's publisher, Joseph Johnson, suggested that she should write a book about the reasons why women should be represented in Parliament. It took her six weeks to write Vindication of the Rights of Women. She told her friend, William Roscoe: "I am dissatisfied with myself for not having done justice to the subject. Do not suspect me of false modesty. I mean to say, that had I allowed myself more time I could have written a better book, in every sense of the word."

In the book Wollstonecraft attacked the educational restrictions that kept women in a state of "ignorance and slavish dependence." She was especially critical of a society that encouraged women to be "docile and attentive to their looks to the exclusion of all else." Wollstonecraft described marriage as "legal prostitution" and added that women "may be convenient slaves, but slavery will have its constant effect, degrading the master and the abject dependent." She added: " I do not wish them (women) to have power over men; but over themselves".

The ideas in Wollstonecraft's book were truly revolutionary and caused tremendous controversy. Horace Walpole described Wollstonecraft as a "hyena in petticoats". Mary Wollstonecraft argued that to obtain social equality society must rid itself of the monarchy as well as the church and military hierarchies. Mary Wollstonecraft's views even shocked fellow radicals. Whereas advocates of parliamentary reform such as Jeremy Bentham and John Cartwright had rejected the idea of female suffrage, Wollstonecraft argued that the rights of man and the rights of women were one and the same thing.

Edmund Burke continued his attack on the radicals in Britain. He described the London Corresponding Society and the Unitarian Society as "loathsome insects that might, if they were allowed, grow into giant spiders as large as oxen". King George III issued a proclamation against seditious writings and meetings, threatening serious punishments for those who refused to accept his authority.

In November, 1792, Mary Wollstonecraft decided to move to Paris in an effort to get away from her unhappy love affair with Henry Fuseli: "I intend no longer to struggle with a rational desire, so have determined to set out for Paris in the course of a fortnight or three weeks." She joked that "I am still a spinster on the wing... At Paris I might take a husband for the time being, and get divorced when my truant heart longed again to nestle with old friends."

Mary arrived in Paris on 11th December at the start of the trial of King Louis XVI. She stayed in a small hotel and watched events from the window of her room: "Though my mind is calm, I cannot dismiss the lively images that have filled my imagination all the day... Once or twice, lifting my eyes from the paper, I have seen eyes glare through a glass-door opposite my chair, and bloody hands shook at me... I am going to bed - and, for the first time in my life, I cannot put out the candle."

Also in Paris at this time was Tom Paine, William Godwin, Joel Barlow, Thomas Christie, John Hurford Stone, James Watt and Thomas Cooper. She also met the poet, Helen Maria Williams. Mary wrote to her sister, Everina, that "Miss Williams has behaved very civilly to me, and I shall visit her frequently, because I rather like her, and I meet French company at her house. Her manners are affected, yet her simple goodness of her heart continually breaks through the varnish, so that one would be more inclined, at least I should, to love than admire her."

In March 1793 Mary met the writer, Gilbert Imlay, whose novel, The Emigrants, had just been published. The book appealed to Mary "because it advocated divorce and contained a portrait of a brutal and tyrannical husband". Mary was thirty-four and Imlay was five years older. "He was a handsome man, tall, thin and easy in his manner". Wollstonecraft was immediately attracted to him and described him as "a most natural, unaffected creature".

William Godwin, who witnessed the relationship while he was in Paris, claims that her personality changed during this period. "Her confidence was entire; her love was unbounded. Now, for the first time in her life, she gave a loose to all the sensibilities of her nature... Her whole character seemed to change with a change of fortune. Her sorrows, the depression of her spirits, were forgotten, and she assumed all the simplicity and the vivacity of a youthful mind... She was playful, full of confidence, kindness and sympathy. Her eyes assumed new lustre, and her cheeks new colour and smothness. Her voice became cheerful; her temper overflowing with universal kindness: and that smile of bewitching tenderness from day to day illuminated her countenance, which all who knew her will so well recollect."

Mary decided to live with Imlay. She wrote about those "sensations that are almost too sacred to be alluded to". The German revolutionary, George Forster in July 1793, met Mary soon after her relationship with Imlay began. "Imagine a five or eight and twenty year old brown-haired maiden, with the most candid face, and features which were once beautiful, and are still partly so, and a simple steadfast character full of spirit and enthusiasm; particularly something gentle in eye and mouth. Her whole being is wrapped up in her love of liberty. She talked much about the Revolution; her opinions were without exception strikingly accurate and to the point."

Mary gave birth to a girl on 14th May 1794. She named her Fanny after her first love, Fanny Blood. She wrote to a friend about how tenderly she and Gilbert loved the new child: "Nothing could be more natural or easy than my labour. My little girl begins to suck so manfully that her father reckons saucily on her writing the second part of the Rights of Women."

In August 1794, Gilbert told Mary he had to go to London on business and he would make arrangements for her to join him in a few months. In reality he had deserted her. "When I first received your letter, putting off your return to an indefinite time, I felt so hurt that I know not what I wrote. I am now calmer, though it was not the kind of wound over which time has the quickest effect; on the contrary, the more I think, the sadder I grow... What sacrifices have you not made for a woman you did not respect! But I will not go over this ground. I want to tell you that I do not understand you."

Mary returned to England in April 1795 but Imlay was unwilling to live with her and keep up appearances like a conventional husband. Instead he moved in with an actress "exposing Mary to public humiliation and forcing her to acknowledge openly the failure of her brave social experiment... it is one thing to defy the opinion of the world when you are happy, another altogether to endure it when you are miserable." Mary found it especially humiliating that his "desire for her had lasted scarcely more than a few months".

One night in October 1795, she jumped off Putney Bridge into the Thames. By the time she had floated two hundred yards downstream she was seen by a couple of waterman who managed to pull her out of the river. She later wrote: "I have only to lament, that, when the bitterness of death was past, I was inhumanly brought back to life and misery. But a fixed determination is not to be baffled by disappointment; nor will I allow that to be a frantic attempt, which was one of the calmest acts of reason. In this respect, I am only accountable to myself. Did I care for what is termed reputation, it is by other circumstances that I should be dishonoured."

Joseph Johnson managed to persuade her return to writing. In January 1796 he published a pamphlet entitled Letters Written During a Short Residence in Denmark, Norway and Sweden. Mary was a good travel writer and provided some good portraits of the people she met in these countries. From a literary standpoint it was probably Wollstonecraft's best book. One critic commented that "If ever there was a book calculated to make a man in love with its author this appears to me to be the book".

In March 1796, Mary wrote to Gilbert Imlay to tell them that she had finally accepted that their relationship was over: "I now solemnly assure you, that this is an eternal farewell... I part with you in peace". Mary was now open to starting another relationship. She was visited several times by the artist, John Opie, who had recently obtained a divorce from his wife. Robert Southey also showed interest and told a friend that she was the person he liked best in the literary world. He said her face was marred only by a slight look of superiority, and that "her eyes are light brown, and, though the lid of one of them is affected by a little paralysis, they are the most meaning I ever saw".

Her friend, Mary Hays, invited her to a small party where renewed her acquaintance with the philosopher, William Godwin. Although aged 40 he was still a bachelor and for most of his life he had shown little interest in women. He had recently published Enquiry into Political Justice and William Hazlitt had commented that Godwin "blazed as a sun in the firmament of reputation".

The couple enjoyed going to the theatre together and going to dinner with painters, writers and politicians, where they enjoyed discussing literary and political issues. Godwin later recalled: "The partiality we conceived for each other, was in that mode, which I have always regarded as the purest and most refined of love. It grew with equal advances in the mind of each. It would have been impossible for the most minute observer to have said who was before, and who was after... I am not conscious that either party can assume to have been the agent or the patient, the toil-spreader or the prey, in the affair... I found a wounded heart... and it was my ambition to heal it."

Mary Wollstonecraft married William Godwin in March, 1797 and soon afterwards, a second daughter, Mary, was born. The baby was healthy but the placenta was retained in the womb. The doctor's attempt to remove the placenta resulted in blood poisoning and Mary died on 10th September, 1797.

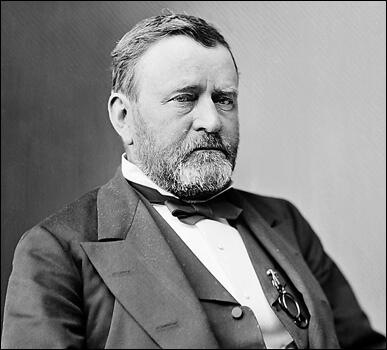

On this day in 1822 Ulysses S. Grant, the son of a tanner, was born in Point Pleasant, Ohio. He entered the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1839. An outstanding horseman, he was unable to join the cavalry after graduating 21st in a class of 39. He joined the 4th Infantry Regiment as a second lieutenant and served as a regimental quartermaster during the Mexican War (1846-48).

After the war he was stationed on the Pacific Coast. It was during this period he developed a drink problem. This resulted in his being forced to resign from the United States Army in 1854.

Grant worked as a firewood peddler, real estate salesman and as a farmer near St. Louis, before becoming a clerk in his family's tannery and leather store in Galenta, Illinois.

An opponent of slavery, on the outbreak of the Civil War, Grant offered his services to the Union Army. He was commissioned as colonel of the 21st Illinois Volunteers. Even before he had engaged the Confederate forces, Grant was promoted to the rank of brigadier-general and placed in charge of the District of South-East Missouri.

On 4th September General Leonidas Polk and a large Confederate Army moved into Kentucky and began occupying high ground overlooking the Ohio River. Grant now moved his troops into Kentucky and quickly gained control of the mouths of the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers as they flowed into the Ohio. The Union Army now controlled the main waterway into the heartland of the Confederacy.

In February, 1862 Grant took his army along the Tennessee River with a flotilla of gunboats and captured Fort Henry. This broke the communications of the extended Confederate line and Joseph E. Johnston decided to withdraw his main army to Nashville. He left 15,000 men to protect Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River but this was enough and Grant had no difficulty taking this prize as well. With western Tennessee now secured, Abraham Lincoln was now able to set up a Union government in Nashville by appointing Andrew Johnson as its new governor.

The Confederate Army now regrouped and Albert S. Johnston and Pierre T. Beauregard reunited their armies near the Tennessee-Mississippi line. With 55,000 men they now outnumbered the forces led by Ulysses S. Grant. On 6th April the Confederate Army attacked Grant's army at Shiloh. Taken by surprise, Grant's army suffered heavy losses until the arrival of General Don Carlos Buell and reinforcements.

Rumours reached President Abraham Lincoln that Grant was responsible for the Union Army's high casualty rate. Grant was defended by his commanding officer, General Henry Halleck. In early 1863, Halleck convinced Lincoln that Grant was the right man to direct the Vicksburg Campaign.

Edwin M. Stanton, the Secretary of War, heard that Grant was drinking heavily and sent newspaperman, Charles Dana, to spy on him. However, Dana found the rumours were untrue and Grant remained in control of the campaign.

General John Pemberton was placed in charge of defending the fortifications around Vicksburg. After two failed assaults, Grant decided to starve Pemberton out. This strategy proved successful and on 4th July, 1863, Pemberton surrendered the city. The western Confederacy was now completely isolated from the eastern Confederacy and the Union Army had total control of the Mississippi River.

President Abraham Lincoln described Grant's campaign as "one of the most brilliant in the world." He wrote to Grant that he had disagreed with Grant's tactics but added: "I now wish to make the personal acknowledgment that you were right, and I was wrong." Grant was promoted to the rank of major general. In October, Lincoln put Grant in control of all armies from the Alleghenies to the Mississippi.

Lincoln rejected Grant's plan to invade Alabama and Georgia. He also complained about Grant's willingness to keep the president informed of his actions. Lincoln commented that "General Grant is a copious worker, and fighter, but a very meagre writer, or telegrapher." Despite his doubts about Grant, in March, 1864, he was named lieutenant general and the commander of the Union Army.

Ulysses S. Grant joined the Army of the Potomac where he worked closely with George Meade and Philip Sheridan. They crossed the Rapidan and entered the Wilderness. When Lee heard the news he sent in his troops, hoping that the Union's superior artillery and cavalry would be offset by the heavy underbrush of the Wilderness. Fighting began on the 5th May and two days later smoldering paper cartridges set fire to dry leaves and around 200 wounded men were either suffocated or burned to death. Of the 88,892 men that Grant took into the Wilderness, 14,283 were casualties and 3,383 were reported missing. Robert E. Lee lost 7,750 men during the fighting.

After the battle Grant moved south and on May 26th sent Philip Sheridan and his cavalry ahead to capture Cold Harbor from the Confederate Army. Lee was forced to abandon Cold Harbor and his whole army well dug in by the time the rest of the Union Army arrived. Grant's ordered a direct assault but afterwards admitted this was a mistake losing 12,000 men "without benefit to compensate".

Grant now headed quickly towards Richmond and was able to take Petersburg before Robert E. Lee had time to react. However, Pierre T. Beauregard was able to protect the route to the city before the arrival of Lee's main army forced Ulysses S. Grant to prepare for a siege.

Grant gave William Sherman the task of destroying the Confederate Army in Tennessee. Joseph E. Johnson and his army retreated and after some brief skirmishes the two sides fought at Resaca (14th May), Adairsvile (17th May), New Hope Church (25th May), Kennesaw Mountain (27th June) and Marietta (2nd July). President Jefferson Davis was unhappy about Johnson's withdrawal policy and on 17th July replaced him with the more aggressive John Hood. He immediately went on the attack and hit George H. Thomas and his men at Peachtree Creek. Hood was badly beaten and lost 2,500 men. Two days later he took on William Sherman at the Battle of Atlanta and lost another 8,000 men.

Grant continued to have disagreements with President Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton. Grant defended generals such as Benjamin Butler, Nathaniel Banks and Henry Thomas, who Lincoln wanted to remove from power. Grant and Lincoln also disagreed about the strategy employed in the Shenandoah Valley.

In the summer of 1864 General Robert E. Lee sent Major General Jubal Early up the Shenandoah Valley to threaten Washington. President Abraham Lincoln demanded that Grant personally took command of the army defending the capital. In his memoirs Grant made it clear that he disagreed with this policy: "The Shenandoah Valley was very important to the Confederates, because it was the principal storehouse they now had for feeding their armies about Richmond. It was well known that they would make a desperate struggle to maintain it. It had been the source of a great deal of trouble to us heretofore to guard that outlet to the north, partly because of the incompetency of some of the commanders, but chiefly because of the interference from Washington. It seemed to be the policy of General Halleck and Secretary Stanton to keep any force sent there, in pursuit of the invading army, moving right and left so as to keep between the enemy and our capital".

In August 1864, Grant sent Philip Sheridan and 40,000 soldiers into the Shenandoah Valley. Sheridan soon encountered troops led by Jubal Early and after a series of minor defeats Sheridan eventually gained the upper hand. His men now burnt and destroyed anything of value in the area and after defeating Early in another large-scale battle on 19th October, the Union Army, for the first time, held the valley. William Sherman removed all resistance in the valley when he marched to Southern Carolina in early 1865.

In August 1864 the Union Army made another attempt to take control of the Shenandoah Valley. Philip Sheridan and 40,000 soldiers entered the valley and soon encountered troops led by Jubal Early who had just returned from Washington. After a series of minor defeats Sheridan eventually gained the upper hand. His men now burnt and destroyed anything of value in the area and after defeating Early in another large-scale battle on 19th October, the Union Army, for the first time, held the Shenandoah Valley.

On 1st April, 1865, Grant sent Philip Sheridan to Five Forks. The Confederates, led by Major General George Pickett, were overwhelmed and lost 5,200 men. On hearing the news, Robert E. Lee decided to abandon Richmond. President Jefferson Davis, his family and government officials, was forced to flee from Richmond. The Union Army took control of Richmond and on 4th April Abraham Lincoln entered the city.

Robert E. Lee was only able to muster an army of 8,000 men. He probed the Union Army at Appomattox but faced by 110,000 men he decided the cause was hopeless. He contacted Grant and after agreeing terms on 9th April, surrendered his army at Appomattox Court House. Grant issued a brief statement: "The war is over; the rebels are our countrymen again and the best sign of rejoicing after the victory will be to abstain from all demonstrations in the field."

Grant attended the Cabinet meeting on 14th April, 1865. However, he declined the offer of accompanying Abraham Lincoln to the Ford Theatre that night as he wanted to see his sons in New Jersey. This decision probably saved his life as John Wilkes Booth and his fellow conspirators were planning to kill Grant as well as Lincoln.

In August 1867, President Andrew Johnson sacked Edwin M. Stanton and appointed Grant as his Secretary of War. When Congress insisted upon Stanton's reinstatement, Grant resigned. Johnson was furious as he believed Grant would stay in office despite the expected objections of Congress.

In 1868 the Republican Party nominated Grant for president. His running mate was Schuyler Colfax, a man associated with the Radical Republican. Grant and Colfax won 26 states out of 34. Three states, Virginia, Mississippi and Texas, had no vote as they had not been yet admitted to the Union. However, Grant only won 52.7 per cent of the popular vote and only narrowly beat his Democratic opponent, Horatio Seymour.

At 46, Grant was the youngest man to be elected president. His first administration included Elihu Washburne (secretary of State), George Boutwell (Secretary of the Treasury), William T. Sherman (Secretary of War), John Creswell (Postmaster General) and Ebenezer Hoar (Attorney General). Later additions included Hamilton Fish (Secretary of State), George H. Williams (Attorney General), William Belknap (Secretary of War) and Zachariah Chandler (Secretary of the Interior).

Politically inexperienced, he had problems dealing with Congress. However, he was popular with the people of America and in 1872 easily defeated his opponent, Horace Greeley. Grant's second term was plagued by corruption and scandal. He announced that he intended to "Let no man escape" but he was criticized for the way he dealt with the situation when Orville Babcock, his private secretary, and William Belknap, his Secretary of War, were accused of corruption. Although loyally defended by his friend, Thomas Nast, the political cartoonist, the "maker of presidents", these events severely damaged his reputation. When Grant's period of office came to an end in 1877, he announced to the American people, "Failures have been errors of judgment, not of intent."

In 1881 Ulysses S. Grant and his son became involved in the investment firm of Grant & Ward. Grant encouraged others to invest in this company and his reputation was again damaged when the firm collapsed and it was discovered that his partner, Ferdinand Ward, was guilty of corruption. With the support of his friend, Mark Twain, Grant began work on his memoirs. Suffering from throat cancer, Grant completed his autobiography, The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant, shortly before his death on 23rd July, 1885.

On this day 1839 The Northern Star reported that the Hyde Chartist Society contained 300 men and 200 women. The newspaper quoted one of the male members as saying that the women were more militant than the men, or as he put it: "the women were the better men". These women's groups were often very large, the Birmingham Charter Association for example, had over 3,000 female members.

Susanna Inge was an important figure in the Chartist movement. As she explained in an article for The Northern Star in July, 1842. "As civilisation advances man becomes more inclined to place woman on an equality with himself, and though excluded from everything connected with public life, her condition is considerably improved". She went on to urge women to “assist those men who will, nay, who do, place women in on equality with themselves in gaining their rights, and yours will be gained also".

In October 1842, Susanna Inge and Mary Ann Walker attempted to establish a Female Chartist Association. Inge argued that in time women should be given the vote. However, she felt before this could happen women "ought to be better educated, and that, if she were, so far as mental capacity, she would in every respect be the equal of man”.

This plan to form a Female Chartist Association was criticised by some male Chartists. One declared that he "did not consider that nature intended women to partake of political rights". He argued that women were "more happy in the peacefulness and usefulness of the domestic hearth, than in coming forth in public and aspiring after political rights".

It was also suggested that if a "young gentleman" might try "to influence her vote through his sway over her affection". Mary Ann Walker responded by claiming that "she would treat with womanly scorn, as a contemptible scoundrel, the man who would dare to influence her vote by any undue and unworthy means; for if he were base enough to mislead her in one way, he would in another.”

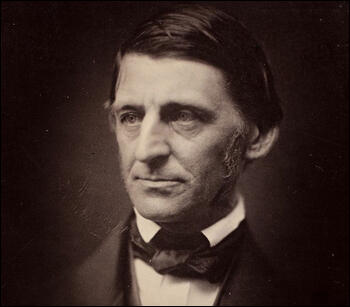

On this day in 1882 Ralph Waldo Emerson died. Emerson was born in Boston on 25th May, 1803. After graduating from Harvard University he became a minister of the Unitarian Church in 1829.

The death of his first wife in 1831 resulted in him questioning his religious beliefs. The following year he resigned his ministry and toured Europe. While in England he met Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Wordsworth and Thomas Carlyle.

On his return to the United States, Emerson remarried and settled in Concorde. His first book, Nature, was published in 1836. This was followed by The American Scholar. Emerson also wrote for The Dial and in 1842 became its editor.

Emerson met a befriended Henry David Thoreau who, for a while, worked as his handyman. Under the influence of Emerson, Thoreau wrote Civil Disobedience (1849). The two men shared the belief that it was morally justified to peacefully resist unjust laws. This philosophy was reflected in his collection of lectures, Representative Men (1850) and his campaign against slavery.

A member of the Republican Party, Emerson fully supported Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War. When Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation Emerson called it a momentous day for the United States.

Later books by Emerson include English Traits (1856), The Conduct of Life (1860), Society and Solitude (1870) and Letters and Social Aims (1876).

Ralph Waldo Emerson died on 27th April, 1882.

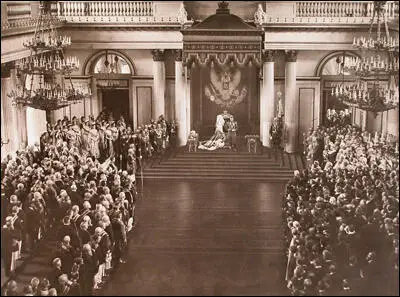

On this day in 1906 the State Duma of the Russian Empire meets for the first time. A British journalist, Maurice Baring, described the members taking their seats on the first day: "Peasants in their long black coats, some of them wearing military medals... You see dignified old men in frock coats, aggressively democratic-looking men with long hair... members of the proletariat... dressed in the costume of two centuries ago... There is a Polish member who is dressed in light-blue tights, a short Eton jacket and Hessian boots... There are some socialists who wear no collars and there is, of course, every kind of headdress you can conceive."

Several changes in the composition of the Duma had been changed since the publication of the October Manifesto. Nicholas II had also created a State Council, an upper chamber, of which he would nominate half its members. He also retained for himself the right to declare war, to control the Orthodox Church and to dissolve the Duma. The Tsar also had the power to appoint and dismiss ministers. At their first meeting, members of the Duma put forward a series of demands including the release of political prisoners, trade union rights and land reform. The Tsar rejected all these proposals and dissolved the Duma.

In April, 1906, Nicholas II forced Sergi Witte to resign and asked the more conservative Peter Stolypin to become Chief Minister. Stolypin was the former governor of Saratov and his draconian measures in suppressing the peasants in 1905 made him notorious. At first he refused the post but the Tsar insisted: "Let us make the sign of the Cross over ourselves and let us ask the Lord to help us both in this difficult, perhaps historic moment." Stolypin told Bernard Pares that "an assembly representing the majority of the population would never work".

Stolypin attempted to provide a balance between the introduction of much needed land reforms and the suppression of the radicals. In October, 1906, Stolypin introduced legislation that enabled peasants to have more opportunity to acquire land. They also got more freedom in the selection of their representatives to the Zemstvo (local government councils). "By avoiding confrontation with peasant representatives in the Duma, he was able to secure the privileges attached to nobles in local government and reject the idea of confiscation."

However, he also introduced new measures to repress disorder and terrorism. On 25 August 1906, three assassins wearing military uniforms, bombed a public reception Stolypin was holding at his home on Aptekarsky Island. Stolypin was only slightly injured, but 28 others were killed. Stolypin's 15-year-old daughter had both legs broken and his 3-year-old son also had injuries. The Tsar suggested that the Stolypin family moved into the Winter Palace for protection.

Elections for the Second Duma took place in 1907. Peter Stolypin, used his powers to exclude large numbers from voting. This reduced the influence of the left but when the Second Duma convened in February, 1907, it still included a large number of reformers. After three months of heated debate, Nicholas II closed down the Duma on the 16th June, 1907. He blamed Lenin and his fellow-Bolsheviks for this action because of the revolutionary speeches that they had been making in exile.

Members of the moderate Constitutional Democrat Party (Kadets) were especially angry about this decision. The leaders, including Prince Georgi Lvov and Pavel Milyukov, travelled to Vyborg, a Finnish resort town, in protest of the government. Milyukov drafted the Vyborg Manifesto. In the manifesto, Milyukov called for passive resistance, non-payment of taxes and draft avoidance. Stolypin took revenge on the rebels and "more than 100 leading Kadets were brought to trial and suspended from their part in the Vyborg Manifesto."

Stolypin's repressive methods created a great deal of conflict. Lionel Kochan, the author of Russia in Revolution (1970), pointed out: "Between November 1905 and June 1906, from the ministry of the interior alone, 288 persons were killed and 383 wounded. Altogether, up to the end of October 1906, 3,611 government officials of all ranks, from governor-generals to village gendarmes, had been killed or wounded." (19) Stolypin told his friend, Bernard Pares, that "in no country is the public more anti-governmental than in Russia".

On this day in 1915 the New York Tribune reports on poison gas on the Western Front. "The German troops, who followed up this advantage with a direct attack, held inspirators in their mouths, these preventing them from being overcome by the fumes. The effect of the noxious trench gas seems to be slow in wearing away. The men come out of their violent nausea in a state of utter collapse. Some of the rescued have already died from the after effects. How many of the men left unconscious in the trenches when the French broke died from the fumes it is impossible to say, since those trenches were at once occupied by the Germans."

Poisonous gases were known about for a long time before the First World War but military officers were reluctant to use them as they considered it to be a uncivilized weapon. The French Army were the first to employ it as a weapon when in the first month of the war they fired tear-gas grenades at the Germans.

In October 1914 the German Army began firing shrapnel shells in which the steel balls had been treated with a chemical irritant. The Germans first used chlorine gas cylinders in April 1915 when it was employed against the French Army at Ypres. Chlorine gas destroyed the respiratory organs of its victims and this led to a slow death by asphyxiation.

General William Robertson recommended Brigadier General Charles Howard Foulkes to General John French as the best man to organise the retaliation. Foulkes accepted the post he eventually received the title of General Officer Commanding the Special Brigade responsible for Chemical Warfare and Director of Gas Services. He worked closely with scientists working at the governmental laboratories at Porton Down near Salisbury. His biographer, John Bourne, has argued: "Despite Foulkes' energy, the ingenuity of his men and the consumption of expensive resources, gas was ultimately disappointing as a weapon, despite its terrifying reputation."

It was important to have the right weather conditions before a gas attack could be made. When the British Army launched a gas attack on 25th September in 1915, the wind blew it back into the faces of the advancing troops. This problem was solved in 1916 when gas shells were produced for use with heavy artillery. This increased the army's range of attack and helped to protect their own troops when weather conditions were not completely ideal.

After the first German chlorine gas attacks, Allied troops were supplied with masks of cotton pads that had been soaked in urine. It was found that the ammonia in the pad neutralized the poison. Other soldiers preferred to use handkerchiefs, a sock, a flannel body-belt, dampened with a solution of bicarbonate of soda, and tied across the mouth and nose until the gas passed over. It was not until July 1915 that soldiers were given efficient gas masks and anti-asphyxiation respirators.

One disadvantage for the side that launched chlorine gas attacks was that it made the victim cough and therefore limited his intake of the poison. Both sides found that phosgene was more effective poison to use. Only a small amount was needed to make it impossible for the soldier to keep fighting. It also killed its victim within 48 hours of the attack. Advancing armies also used a mixture of chlorine and phosgene called 'white star'.

Mustard Gas (Yperite) was first used by the German Army in September 1917. The most lethal of all the poisonous chemicals used during the war, it was almost odourless and took twelve hours to take effect. Yperite was so powerful that only small amounts had to be added to high explosive shells to be effective. Once in the soil, mustard gas remained active for several weeks. The Germans also used bromine and chloropicrin.

In July 1917, David Lloyd George appointed Winston Churchill as Minister of Munitions and for the rest of the war, he was in charge of the production of tanks, aeroplanes, guns and shells. Clive Ponting, the author of Churchill (1994) has argued: "The technology in which Churchill placed greatest faith though was chemical warfare, which had first been used by the Germans in 1915. It was at this time that Churchill developed what was to prove a life-long enthusiasm for the widespread use of this form of warfare."

Churchill developed a close relationship with Brigadier General Charles Howard Foulkes. Churchill urged Foulkes to provide him with effective ways of using chemical weapons against the German Army. In November 1917 Churchill advocated the production of gas bombs to be dropped by aircraft. However, this idea was rejected "because it would involve the deaths of many French and Belgian civilians behind German lines and take too many scarce servicemen to operate and maintain the aircraft and bombs."

On 6th April, 1918, Churchill told Louis Loucheur, the French Minister of Armaments: "I am... in favour of the greatest possible development of gas-warfare." In a paper he produced for the War Cabinet he argued for the widespread deployment of tanks, large-scale bombing attacks on German civilians and the mass use of chemical warfare. Foulkes told Churchill that his scientists were working on a very powerful new chemical weapon codenamed "M Device".

According to Giles Milton, the author of Russian Roulette: How British Spies Thwarted Lenin's Global Plot (2013): "Trials at Porton suggested that the M Device was indeed a terrible new weapon. The active ingredient in the M Device was diphenylaminechloroarsine, a highly toxic chemical. A thermogenerator was used to convert this chemical into a dense smoke that would incapacitate any soldier unfortunate enough to inhale it... The symptoms were violent and deeply unpleasant. Uncontrollable vomiting, coughing up blood and instant and crippling fatigue were the most common features.... Victims who were not killed outright were struck down by lassitude and left depressed for long periods."

Churchill hoped that he would be able to use the top secret "M Device", an exploding shell that released a highly toxic gas derived from arsenic. Foulkes called it "the most effective chemical weapon ever devised". The scientist, John Haldane, later described the impact of this new weapon: "The pain in the head is described as like that caused when fresh water gets into the nose when bathing, but infinitely more severe... accompanied by the most appalling mental distress and misery." Foulkes argued that the strategy should be "the discharge of gas on a stupendous scale". This was to be followed by "a British attack, bypassing the trenches filled with suffocating and dying men". However, the war came to an end in November, 1918, before this strategy could be deployed.

It has been estimated that the Germans used 68,000 tons of gas against Allied soldiers. This was more than the French Army (36,000) and the British Army (25,000). An estimated 91,198 soldiers died as a result of poison gas attacks and another 1.2 million were hospitalized. The Russian Army, with 56,000 deaths, suffered more than any other armed force.

Brigadier General Charles Howard Foulkes published Gas: The True Story of the Special Brigade in 1934. In the book Foulkes claims that the total British casualties due to gas amounted to 181,053 of which 6,109 were fatal. However, he admitted that this did not include the men who died after the war due to the effects of gas poisoning. He added that the German Army had not published details of their gas casualties.

On this day in 1927 civil rights activist Coretta Scott was born. Coretta Scott was born in Marion, Alabama, on 27th April, 1927. Her father was a lumber carrier who did badly during the Great Depression. The family was so poor that Coretta had to walk three miles to school every day.

After graduating from Antioch College in Ohio in 1951, she enrolled at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston. In 1953 Coretta married Martin Luther King and over the next few years gave birth to four children.

King became pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. Coretta was active in the civil rights movement and took part in the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the famous March on Washington in August, 1963.

After the assassination of Martin Luther King Coretta continued to campaign for equal rights and founded the Center for Non-Violent Social Change in Atlanta. Her book, My Life with Martin Luther King was published in 1969.

Coretta's greatest success was in establishing Martin Luther King Day, commemorating her husband's birthday on January 15 as a US national holiday.

Coretta Scott King died in her sleep on 31st January, 2006.

On this day in 1932 Hart Crane his sexual advances to a male crew member were rejected. He had been drinking heavily when several passengers heard him call out "goodbye, everybody" before jumping overboard.

Hart Crane, the son of a successful drug store owner, was born in Garretsville, Ohio on 21st July 1899. His parents divorced in April 1917 and soon afterwards he left high school and moved to New York City. Over the next few years he did a variety of jobs including a shipyard worker and as an advertising copywriter.

Crane told Walker Evans that he became a homosexual after being seduced by an older man in 1919 in Akron, Ohio, where he was employed as a clerk in one of his father’s candy stores. However, because of his Christian Scientist upbringing, he never came to terms with his sexuality.

Crane went to live in Greenwich Village where he became close friends with Malcolm Cowley and his wife Peggy Baird. Cowley encouraged Hart to write but he later admitted that he had a serious drink problem: "Hart drank to write: he drank to invoke the visions that his poems are intended to convey."

On 17th October, 1921, wrote to William Wright explaining what he was trying to achieve as a poet: "I can only apologize by saying that if my work seems needlessly sophisticated it is because I am only interested in adding what seems to me something really new to what has been written. Unless one has some new, intensely personal viewpoint to record, say on the eternal feelings of love, and the suitable personal idiom to employ in the act, I say, why write about it?.... I admit to a slight leaning toward the esoteric, and am perhaps not to be taken seriously. I am fond of things of great fragility, and also and especially of the kind of poetry John Donne represents, a dark musky, brooding, speculative vintage, at once sensual and spiritual, and singing rather the beauty of experience than innocence"

Eugene O'Neill was one of his earliest supporters. Crane wrote to his mother on 3rd February, 1924: "O'Neill ... recently told a mutual friend of ours that he thinks me the most important writer of all in the group of younger men with whom I am generally classed".

In 1924 Hart Crane began an affair with Emil Opffer, a Danish merchant mariner. According to one biographer: "With him, an emotional relationship developed in which Crane was intensely engaged. Crane never found a single partner with whom to share his life, and after Opffer, he may have felt such a partner could never be found. His affairs were temporary, mostly anonymous, and sometimes violent." His relationship with Opffer inspired a series of poems that became known as Voyages. These poems were included in his first collection, White Buildings (1926).

Crane's poetry was not popular but he had some important supporters. E. E. Cummings said that "Crane’s mind was no bigger than a pin, but it didn’t matter; he was a born poet." Another reviewer argued that "Crane masterfully uses variations in rhythm and syntax to establish a powerful, nearly invisible foundation that provides a dynamic forward movement to a poetic line that is bristling with significance, its diction drawn from virtually dozens of conflicting and overlapping registers."

Crane was a great admirer of the work of T.S. Eliot but disliked his pessimism. He also thought The Waste Land was too critical of the modern world and attempted to write poems that provided a balanced view of contemporary developments. His friend, Malcolm Cowley, later revealed that Crane could only write under the influence of alcohol. "But the recipe could be followed for a few years at the most, and it was completely effective only for two periods of about a month each, in 1926 and 1927, when working at top speed he finished most of the poems included in The Bridge. After that more and more alcohol was needed, so much of it that when the visions came he was incapable of putting them on paper."

A second volume of poems, The Bridge, appeared in 1930 to mixed reviews. Cudworth Flint wrote: "This poem seems to me indubitably the work of a man of genius, and it contains passages of compact imagination and compelling rhythms. But its central intention, to give to America a myth embodying a creed which may sustain us somewhat as Christianity has done in the past, the poem fails." However, Yvor Winter argued: "These poems illustrate the dangers inherent in Mr. Crane’s almost blind faith in his moment-to-moment inspiration, the danger that the author may turn himself into a kind of stylistic automaton, the danger that he may develop a sentimental leniency toward his vices and become wholly their victim, instead of understanding them and eliminating them."

The publication of The Bridge meant that Hart Crane was recognized as an important poet and Eda Lou Walton announced he was being included in her New York University course in contemporary poetry. He was also awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1931. During this period he began an affair with Peggy Baird. It was his only heterosexual relationship and it was probably instigated by Peggy, who had a reputation for being very promiscuous. She told her friend, Dorothy Day that sex was "a barrier that kept men and women from fully understanding each other, and thus a barrier to be broken down". In 1931 Peggy left her husband, Malcolm Cowley, and went to live with Crane in Mexico.

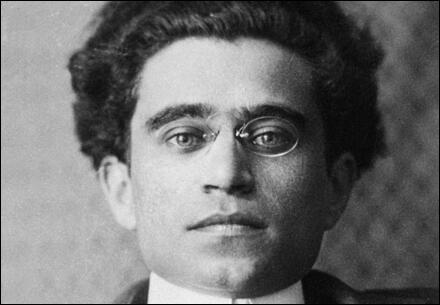

On this day in 1937 Antonio Gramsci died in prison. Gramsci was born in Ales, Sardina, on 22nd January 1891. Although born into poverty he was extremely intelligent and in 1911 won a scholarship to Turin University. While a student in Italy Gramsci became involved in politics. He joined the Italian Socialist Party in 1914 and inspired by the Bolshevik Revolution he took an active part in the workers' occupation of factories in 1918.

Gramsci was disillusioned by the unwillingness of the Italian Socialist Party to advocate revolutionary struggle. Encouraged by Vladimir Lenin and the Comintern, Gramsci joined with Palmiro Togliatti to form the Italian Communist Party in 1921.

Gramsci visited the Soviet Union in 1922 and two years later became leader of the communists in parliament. An outspoken critic of Benito Mussolini and his fascist government, he was arrested and imprisoned in 1928.

While in prison Gramsci wrote a huge collection of essays which later established his reputation as one of the most important radical theorists since Karl Marx. In his essays he criticized those who had turned Marxism into a closed system, with immutable laws. He argued that the collapse of capitalism and its replacement with socialism was not inevitable and rejected Lenin's belief that revolution could be brought about by a small, dedicated minority. While this worked in a backward country such as Russia in 1917 he doubted it would be successful in more advanced countries in Europe.

In his writings Gramsci emphasized the importance of the way the ruling class controlled institutions such as the press, radio and trade unions. Gramsci believed that the only way the power of the state could be overthrown was when the majority of the workers desired revolution.

Antonio Gramsci's book, Prison Notebooks, was published in 1947 and his theories, that advocated persuasion, consent and doctrinal flexibility, had a major influence on left-wing radicals in post-war Europe.

On this day in 1939, Neville Chamberlain made the controversial decision to introduce conscription, although repeated pledges had been given by him against such a step. It is claimed that Leslie Hore-Belisha, Secretary of State for War, had forced Chamberlain to change his mind. Both members of the Labour Party and the Liberal Party objected to the measure and according to Winston Churchill because of "the ancient and deep-rooted prejudice which has always existed in England against Compulsory Military Service."

Clement Attlee argued: "Whilst prepared to take all necessary steps to provide for the safety of the nation and the fulfillment of its international obligations, this House regrets that His Majesty's Government in breach of their pledges should abandon the voluntary principle which has not failed to provide the man-power needed for defence, and is of opinion that the measure proposed is ill-conceived, and, so far from adding materially to the effective defence of the country, will promote division and discourage the national effort, and is further evidence that the Government's conduct of affairs throughout these critical times does not merit the confidence of the country or this House."

Attlee later attempted to explain why he opposed conscription. He thought this was of doubtful military value and that military conscription might pave the way for industrial conscription. He admitted to Mark Arnold-Forster: "But you must remember the hangover from the last war. The generals were given far too many men. They sacrificed men because they wouldn't use their brains. Didn't happen in the second war."

Parliament passed the Military Training Act by 380 to 143 votes. This introduced conscription for men aged 20 and 21, who were now required to undertake six months' full-time military training. Once this decision had been taken, however, the Labour Party quickly accepted it, and it soon ceased to be contentious. A resolution at the Labour Party Conference calling for non-cooperation in defence measures was defeated by a huge majority - 1,670,000 to 286,000. Attlee and the shadow cabinet continued to oppose any further concessions to Adolf Hitler.

Parliament also passed legislation that protected some important occupations from national service. After consulting with business leaders, the government published the Schedule of Reserved Occupations. Employers were also able to ask for individual key workers employed in one of these occupations not to be conscripted into the armed forces. In January 1939, a handbook sent to every household in the country, which catalogued the various full-time and part-time war jobs. It was designed to check impulsive volunteering by skilled workers and to help others to find the appropriate service. Over the next few months more than 200,000 men had been granted deferment at their employers' request. By the summer of 1939 over 300,000 had volunteered for the armed forces and around 500,000 recruits for the Civil Defence services.

Young men who were not wearing the uniform of the armed forces because they were working in reserved occupations, sometimes came under pressure from the local population: "Matt, my boyfriend, was exempted from call-up for a while because he was needed at home. He worked at Devonport Dockyard building ships. It got embarrassing when people in our village started to whisper: Why isn't he fighting like our men?"

On the outbreak of the Second World War,the regular army and its reserves numbered about 400,000, and there was a roughly equal number of territorials. On the first day of war, Parliament passed the National Service (Armed Forces) Act, under which all men between 18 and 41 were made liable for conscription. The registration of all men in each age group in turn began on 21st October for those aged 20 to 23. The following May, registration had extended only as far as men aged twenty-seven. Richard Titmuss said that the "call-up" seemed "to progress with the speed of an elephant trying to compete in the Derby".

To others the pace was going too fast. Frank Edwards, a 33-year-old, a businessman from Birmingham, wrote in December, 1939: "I think there were some surprised people today when the 22-year-olds were called up, owing to this being sooner than was expected, especially as it was authoritatively stated after the last call up on 21st October that it was not expected the next age group would be called on until the new year."

Muriel Simkin was on honeymoon when war was declared. Soon after she arrived home her husband, John Simkin, and her brother, Jack Hughes, received their call up papers. "We were on our honeymoon when war was declared. We had planned to have a fortnight's holiday but we had to come home after a week. It was not a very good start to our married life... People on the whole were more friendly during the war than they are today - happier even. People helped you out. You had to have a sense of humour. You couldn't get through it without that."

Provision was made in the legislation for people to object to military service. Not only on pacifist grounds, which had been accepted in the First World War, but also on political grounds. Of the first batch of men aged 20 to 23, an estimated 22 in every 1,000 objected and went before local conscientious objection tribunals. The tribunals varied greatly in their attitudes towards conscientious objection to military service, and the proportions of conscientious applications totally rejected ranged from 2 per cent in London to 27 per cent in south-west Scotland. The longer the war continued, the lower the percentage objected to conscription. By the summer of 1940 only 16 in every thousand did so."

The political and moral views of the tribunal chairman were vitally important. It was difficult always to get a fair hearing in London, especially during the Blitz. On one occasion the chairman told the applicant that his request was rejected because "Even God is not a pacifist, for he kills us all in the end". A man could himself apply for postponement of his call-up on grounds of severe personal hardship. Over the whole war more than 200,000 such applications were accepted, and a sizable proportion of the applicants had their postponement renewed."

On this day in 1942 Reinhard Heydrich is assassinated by Czech resistance fighters. On 27th September 1941, Heydrich took up his post as Reich Protector of Bohemia and Moravia. Five days later he announced that the SS intended to "Germanize the Czech vermin." Czech men, women and children were killed in large-scale executions, many staged dramatically in public. These actions resulted in a new nickname, the "Butcher of Prague".

In September, 1941, President Eduard Beneš, the head provisional Czechoslovakian government based in London approached Colin Gubbins, the director of operations of Special Operations Executive (SOE) about the possible assassination of Reinhard Heydrich. "Colonel Moravec enquired whether SOE would help in this project by providing facilities for training and supplying any special weaponry that was required. Gubbins had no hesitation in agreeing, but decided to restrict the knowledge of the Czech approach, and above all of the identity of the probable target, to a very small circle.... Acts of terrorism fell within SOE's charter and, as a senior official of the Sicherheitsdienst, Heydrich was a legitimate target. Moreover, in the last resort Benes and the Czech government were free to do what they liked in their own country without having to seek British approval. However, Gubbins pointed out to Moravec that an assassination of this sort was a purely political act which, even if unsuccessful, would result in wholesale reprisals for which, in his view, there was insufficient military justification."

Stewart Menzies, the head of MI6 gave permission for Gubbins to organize the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich. This was the only Nazi leader that the Allies attempted to assassinate. They took this decision knowing that the German Army would take terrible retribution of the people of Czechoslovakia. Interestingly, Gubbins did not tell the Prime Minister Winston Churchill and the Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden about the plot. Eden was especially opposed to this kind of action that he described as this "war crimes business".

The Czech secret service in England provided British-trained assassination agents Jan Kubis and Jozef Gabčík. The two-man team, codenamed Anthropoid, parachuted into the Bohemian hills on 29th December 1941. The drop was over Nehvizdy, a village five miles south of Pilsen. During the time needed to recruit the team they studied Heydrich's movements and habits. He always used the same routes between his country estate at Hradcany Castle and the airport. He always sat in the front seat of his powerful Mercedes car with Klein, the SS driver. Heydrich also did not use a bodyguard or armed escort.

On 23rd May 1942, the Czech underground gave Kubis and Gabčík, Heydrich's schedule for 27th May. "Meanwhile a perfect place for an ambush had been found. It was in the Holesovice suburb were Heydrich's car would have to slow for a right turn from Kirchmayer Blvd toward Troja Bridge and the center of Prague. With time for working out details of their plan Kubis and Gabčík formed their team. Josef Valcik would be on the boulevard about 100 yards from the turn, and he would flash a pocket mirror (pretending to comb his hair) when the victim came into sight. Rena Fafek, Gabcik's girlfriend, would be driven through the turn ahead of the big Mercedes and signal (by wearing a hat or not) whether the team had to deal with two cars or just one. Adolf Opalka was on the left-hand sidewalk across the street from the hit men; Kubis was on the corner watching Valcik:a few yards from him on the right sidewalk, were Gabčík and three other parachutists, Jaroslt Svarc, Josef Bublik, and Jan Hruby.... Just after 10:30 the Anthropoids got the signals: Valcik flashed his mirror, and the lady partisan came through the turn bareheaded. As the unsuspecting Germans followed, a streetcar clanged up from the Troja Bridge to a transfer point on the boulevard. Klein had to slow further for a couple of indecisive pedestrians, then he slammed on the brakes to avoid hitting a man who darted into the street. It was Josef Gabčík who whipped a Sten gun from under his rain coat, leveled it at Heydrich's chest, and calmly pulled the trigger. Nothing happened!"

Heydrich and Klein both stood up and opened fire at Gabčík. Kubis then stepped forward a threw lobbed a grenade at the car. Heydrich was taken to the local hospital, where he underwent an emergency operation. The wound in his side did not appear to be life-threatening, but was full of debris - bits of metal and car upholstery to include cloth, leather, and horsehair near the spleen. Heydrich was reported to be recovering well, but developed blood poisoning and died of septicemia on 4th June 1942.

Karl Frank, Secretary of State for of Bohemia and Moravia, offered a reward of 10 million Czech crowns for the arrest of those involved in the assassination. He also stated: "Whoever shelters these criminals, provides them with help, or, knowing them, does not denounce them, will be shot with his whole family." Adolf Hitler gave orders for the immediate execution of 10,000 Czechs suspected of anti-German activities of anti-German activities. The Gestapo began rounding up suspects and they were sent to Mauthausen concentration camp.

The seven men involved in the assassination hid in the church of St Cyril and St Methodius in Prague. They were betrayed by Karel Curda. Inside were more than a hundred members of the Czech Resistance Movement. The men held out for three weeks until he Germans stormed the church on 18th June 1942. All the men inside were either killed or committed suicide. Four priests were executed on 3rd September for helping the fugitives, and another 252 Czechs were condemned to death at another trial that month for aiding the assassins. Another 256 Czechs were condemned to death for aiding the assassination plot.

As Jacques Delarue, the author of The Gestapo (1962) has pointed out: "Heydrich's death was the signal for the most bloody reprisals. More than three thousand arrests were carried out, and courts-martial at Prague and Brno pronounced 1,350 death sentences.... A gigantic operation was unleashed against the Resistance and the Czech populace. An area of 15,000 square kilometers and 5,000 communes was searched and 657 persons shot on the spot.... Until the end the Nazis harassed the Czech people without ever managing to break their resistance. It had been calculated that 200,000 people passed through the prison of Brno alone, of whom only 50,000 were liberated, the others having been killed or sent to the slow death of the concentration camps. In all, 305,000 Czechs were deported to the camps; only 75,000 emerged alive."