On this day on 24th August

On this day in 1759 William Wilberforce, only son of Robert Wilberforce (1728–1768) and Elizabeth Bird (1730–1798), was born in Kingston upon Hull on 24th August 1759. His paternal grandfather, William Wilberforce (1690–1776), established the family fortunes through the Baltic trade and was twice mayor of Hull.

William was not a strong child and it was said that "his frame from infancy was feeble, his stature small, his eyes weak". He himself said that if "I was not born in less civilised times, when it would have been thought impossible to rear so delicate a child".

William started at Hull Grammar School at the age of seven. He was taught by Isaac Milner who immediately recognised his talent as an orator: "Even then (as a boy) his elocution was so remarkable, that we used to set him upon a table and made him read aloud as an example to the other boys."

In 1768, because of his father's premature death, he was sent to live with an uncle, also William Wilberforce, and his wife, Hannah, at their homes in St James's Place, London, and in Wimbledon. His aunt Hannah, an admirer of John Wesley and George Whitefield and friendly with the Methodists, influenced him towards evangelicalism. When he was 13, his mother decided to remove him from this "dangerous influence" and he became a boarder at Pocklington School.

At seventeen Wilberforce was sent to St. John's College. Following the deaths of his grandfather in 1776 and his childless uncle William in 1777, Wilberforce was an extremely wealthy man. "He could lay claim to a personal fortune in the low hundreds of thousands of pounds, with £100,000 at that time roughly corresponding to £10 million today."

William Wilberforce was shocked by the behaviour of his fellow students at the University of Cambridge and later explained: "I was introduced on the very first night of my arrival to as licentious a set of men as can well be conceived. They drank hard, and their conversation was even worse than their lives." While at university he was introduced to "some of the very worse men that I ever met with in my life". Wilberforce spent his time "entertaining, socializing, attending balls and visiting friends".

After leaving university he showed no interest in the family business, and while still at Cambridge he decided to pursue a political career and at the age of twenty, he decided to become a candidate in the forthcoming parliamentary election in Kingston upon Hull in September 1780. His opponent was a rich and powerful member of the nobility, and Wilberforce had to spend nearly £9,000 on the 1,500 voters to become elected. In the House of Commons Wilberforce mainly supported the the Tory government led by Lord North but preferred the label "Independent".

Wilberforce was not an active member of the House of Commons and did not make his first speech until May 1781 when he argued that the proposed legislation, the Prevention of Smuggling Act, that "it would not only be severe, but unjust to confiscate the vessel" of a captain involved in these illegal trade. The second speech also reflected the interests of his electors when he requested government contracts for Hull. In fact he spent most of his time at the three most important gentlemen's clubs, White's, Boodle's and Brooks's, in London.

At the time he was a heavy gambler and later wrote "they considered me a fine, fat pigeon whom they might pluck". However, it was the experiences of others that eventually brought this addiction to an end. He saw some young aristocrats lose their entire estates. He later pointed out that most of the big losers were "heirs to future fortunes" and came to the conclusion that he could not afford to gamble.

During this period he became very friendly with William Pitt. The two men had been at Cambridge together, but had spent little time together as Pitt took his education more seriously. Pitt was "astronomically ambitious, but being a younger son had no independent fortune". He therefore did not have the money to stand for a large town such as Hull and had to find a cheaper way to enter Parliament. With the help of his university friend, Charles Manners, 4th Duke of Rutland, secured the patronage of James Lowther, who controlled the pocket borough of Appleby; a by-election in that constituency sent Pitt to the House of Commons in January 1781.

Pitt regularly stayed with Wilberforce at his house in Wimbledon and "for near three months slept almost every night there." The two men, although Tories, began to turn against Lord North. Wilberforce wrote that "while the present Ministry existed there were no prospects of either peace or happiness to this Kingdom". He went on to claim that the actions of North's ministers more "resembled the career of furious madmen than the necessarily vigorous and prudent exertions of able statesmen."

On 19th December 1783, George III appointed Pitt as Prime Minister, even though Lord North and Charles Fox continued to command majority support in the House of Commons. The dismissal by the King of a government with a clear majority, was unconstitutional and a total violation of the settlement of 1688. Pitt, at twenty-four, was by far the youngest Prime Minister in British history. Wilberforce, albeit without government office, was a key supporter of his minority government in its difficult early months.

The historian, Ellen Gibson Wilson, has pointed out: "Wilberforce was little over five feet tall, a frail and elfin figure who in his later years weighed well under 100 pounds. His charm was legendary, his conversation delightful, his oratory impressive. He dressed in the colourful finery of the day and adorned any salon with his amiable manner. Yet his object in life - no less than the transformation of a corrupt society through serious religion - was solemn... Wilberforce, although he rejected a party label, was deeply conservative and a loyal supporter of the government led by his friend William Pitt."

In 1784 Wilberforce became converted to Evangelical Christianity. He joined the Clapham Set, a group of evangelical members of the Anglican Church, centered around Henry Venn, rector of Clapham Church in London. As a result of this conversion, Wilberforce became interested in the subject of social reform. Other members included Hannah More, Granville Sharp, Henry Thornton, Zachary Macaulay, James Stephen, Edward James Eliot, Thomas Gisbourne, John Shore and Charles Grant.

Wilberforce contemplated giving up politics for a life as a clergyman. John Newton, a former slave-trader, who had become a devout Christian, persuaded Wilberforce that he could serve God better by remaining in Parliament and campaigning for social reform. Wilberforce renounced all "things of the flesh". He resigned from all his gentlemen clubs and "exchanged his socializing and entertaining for one of reflection and re-evaluation".

In June 1786 Thomas Clarkson published Essay on the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species, Particularly the African. As Ellen Gibson Wilson has pointed out: "A substantial book (256 pages), it traced the history of slavery to its decline in Europe and arrival in Africa, made a powerful indictment of the slave system as it operated in the West Indian colonies and attacked the slave trade supporting it. In reading it, one is struck by its raw emotion as much as by its strong reasoning."

In 1787 Thomas Clarkson, William Dillwyn and Granville Sharp formed the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Although Sharp and Clarkson were both Anglicans, nine out of the twelve members on the committee, were Quakers. This included John Barton (1755-1789); George Harrison (1747-1827); Samuel Hoare Jr. (1751-1825); Joseph Hooper (1732-1789); John Lloyd (1750-1811); Joseph Woods (1738-1812); James Phillips (1745-1799) and Richard Phillips (1756-1836). Influential figures such as John Wesley, Josiah Wedgwood, James Ramsay, and William Smith gave their support to the campaign. Clarkson was appointed secretary, Sharp as chairman and Hoare as treasurer.

Clarkson approached another sympathiser, Charles Middleton, the MP for Rochester, to represent the group in the House of Commons. He rejected the idea and instead suggested the name of William Wilberforce, who "not only displayed very superior talents of great eloquence, but was a decided and powerful advocate of the cause of truth and virtue." Lady Middleton wrote to Wilberforce who replied: "I feel the great importance of the subject and I think myself unequal to the task allotted to me, but yet I will not positively decline it."

Wilberforce agreed that while people such as Thomas Clarkson worked on gathering evidence and mobilizing public opinion through the committee for the abolition of the slave trade, Wilberforce complemented their work through his exertions in the House of Commons. He also attempted lobbied bishops and prominent laymen. On 28th October, 1787, he wrote in his journal that "God Almighty has set before me two great objects, the suppression of the slave trade and the reformation of manners".

Wilberforce's nephew, George Stephen, was surprised by this choice as he considered him a lazy man and too conservative to do the job and had "too much deferential regard for rank and power: "He worked out nothing for himself; he was destitute of system, and desultory in his habits; he depended on others for information, and laid himself open to misguidance... he required an intellectual walking stick."

Charles Fox was also unsure of Wilberforce's commitment to the anti-slavery campaign. He wrote to Thomas Walker: "There are many reasons why I am glad (Wilberforce) has undertaken it rather than I, and I think as you do, that I can be very useful in preventing him from betraying the cause, if he should be so inclined, which I own I suspect. Nothing, I think but such a disposition, or a want of judgment scarcely credible, could induce him to throw cold water upon petitions. It is from them and other demonstrations of the opinion without doors that I look for success."

Political radicals such as Francis Place hated politicians such as Wilberforce "for their complacency and indifference to poverty in their own country while fighting against the same thing abroad". He described him as "an ugly epitome of the devil". William Hazlitt added: "He preaches vital Christianity to untutored savages, and tolerates its worst abuses in civilised states. He thus shows his respect for religion without offending the clergy."

In May 1788, Charles Fox precipitated the first parliamentary debate on the issue. He denounced the "disgraceful traffic" which ought not to be regulated but destroyed. William Dolben described shipboard horrors of slaves chained hand and foot, stowed like "herrings in a barrel" and stricken with "putrid and fatal disorders" which infected crews as well. With the support of Wilberforce Samuel Whitbread, Charles Middleton and William Smith, Dolben put forward a bill to regulate conditions on board slave ships. The legislation was initially rejected by the House of Lords but after William Pitt threatened to resign as prime minister, the bill passed 56 to 5 and received royal assent on 11th July.

Wilberforce's biographer, John Wolffe, has argued: "Following the publication of the privy council report on 25 April 1789, Wilberforce marked his own delayed formal entry into the parliamentary campaign on 12 May with a closely reasoned speech of three and a half hours, using its evidence to describe the effects of the trade on Africa and the appalling conditions of the middle passage. He argued that abolition would lead to an improvement in the conditions of slaves already in the West Indies, and sought to answer the economic arguments of his opponents. For him, however, the fundamental issue was one of morality and justice. The Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was very pleased with the speech and sent its thanks for his "unparalleled assiduity and perseverance".

William Wilberforce also became involved in other areas of social reform. In August 1789 Wilberforce stayed with Hannah More at her cottage in Blagdon, and on visiting the nearby village of Cheddar and according to William Roberts, the author of Memoirs of the Life and Correspondence of Mrs. Hannah More (1834): they were appalled to find "incredible multitudes of poor, plunged in an excess of vice, poverty, and ignorance beyond what one would suppose possible in a civilized and Christian country". As a result of this experience, More rented a house at Cheddar and engaged teachers to instruct the children in reading the Bible and the catechism. The school soon had 300 pupils and over the next ten years the More sisters opened another twelve schools in the area where the main objective was "to train up the lower classes to habits of industry and virtue".

Michael Jordan, the author of The Great Abolition Sham (2005) has pointed out that More shared Wilberforce's reactionary political views: "More set up local schools in order to equip impoverished pupils with an elementary grasp of reading. This, however, was where her concern for their education effectively ended, because she did not offer her charges the additional skill of writing. To be able to read was to open a door to good ideas and sound morality (most of which was provided by Hannah More through a series of religious pamphlets); writing, on the other hand, was to be discouraged, since it would open the way to rising above one's natural station."

The House of Commons agreed to establish a committee to look into the slave trade. Wilberforce said he did not intend to introduce new testimony as the case against the trade was already in the public record. Ellen Gibson Wilson, a leading historian on the slave trade has argued: "Everyone thought the hearing would be brief, perhaps one sitting. Instead, the slaving interests prolonged it so skilfully that when the House adjourned on 23 June, their witnesses were still testifying."

James Ramsay, the veteran campaigner against the slave trade, was now extremely ill. He wrote to Thomas Clarkson: "Whether the bill goes through the House or not, the discussion attending it will have a most beneficial effect. The whole of this business I think now to be in such a train as to enable me to bid farewell to the present scene with the satisfaction of not having lived in vain." Ten days later Ramsay died from a gastric haemorrhage. The vote on the slave trade was postponed to 1790.

Wilberforce initially welcomed the French Revolution as he believed that the new government would abolish the country's slave trade. He wrote to Abbé de la Jeard on 17th July 1789 commenting that "I sympathize warmly in what is going forward in your country." Clarkson commented: "Mr. Wilberforce, always solicitous for the good of this great cause, was of the opinion that, as commotions have taken place in France, which then aimed at political reforms, it was possible that the leading persons concerned in them might, if an application were made to them judiciously, be induced to take the slave trade into their consideration, and incorporated among the abuses to be done away."

Wilberforce intended to visit France but he was persuaded by friends that it would be dangerous for an English politician to be in the country during a revolution. Wilberforce therefore asked Clarkson to visit Paris on behalf of himself and the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Clarkson was welcomed by the French abolitionists and later that month the government published A Declaration of the Rights of Man asserting that all men were born and remained free and equal.

However, the visit was a failure as Clarkson could not persuade the French National Assembly to discuss the abolition of the slave trade. Marquis de Lafayette said "he hoped the day was near at hand, when two great nations, which had been hitherto distinguished only for their hostility would unite in so sublime a measure (abolition) and that they would follow up their union by another, still more lovely, for the preservation of eternal and universal peace." Clarkson thought Lafayette "as uncompromising an enemy of the slave-trade and slavery, as any man I ever knew".

On his return to England Thomas Clarkson continued to gather information for the campaign against the slave-trade. Over the next four months he covered over 7,000 miles. During this period he could only find twenty men willing to testify before the House of Commons. He later recalled: "I was disgusted... to find how little men were disposed to make sacrifices for so great a cause." There were some seamen who were willing to make the trip to London. One captain told Clarkson: "I had rather live on bread and water, and tell what I know of the slave trade, than live in the greatest affluence and withhold it."

William Wilberforce believed that the support for the French Revolution by the leading members of the Society for the Abolition of Slave Trade was creating difficulties for his attempts to bring an end to the slave trade in the House of Commons. He told Thomas Clarkson: "I wanted much to see you to tell you to keep clear from the subject of the French Revolution and I hope you will." Wilberforce had changed his views on the subject because of the way that radicals such as Thomas Paine had welcomed the French Revolution.

Wilberforce's conservative friends were also very concerned about the other leaders of the anti-slavery movement. Isaac Milner, a leader of the Clapham Set, had a long talk with Clarkson, and then commented to Wilberforce: "I wish him better health, and better notions in politics; no government can stand on such principles as he maintains. I am very sorry for it, because I see plainly advantage is taken of such cases as his, in order to represent the friends of Abolition as levellers."

On 18th April 1791 Wilberforce introduced a bill to abolish the slave trade. Wilberforce was supported by William Pitt, William Smith, Charles Fox, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, William Grenville and Henry Brougham. The opposition was led by Lord John Russell and Colonel Banastre Tarleton, the MP for Liverpool. There was no reasoned justification of slavery or the slave-trade. Thomas Grosvenor, the MP for Chester, acknowledged that it was "not an amiable trade but neither was the trade of a butcher an amiable trade, and yet a mutton chop was, nevertheless, a good thing." One observer commented that it was "a war of the pigmies against the giants of the House". However, on 19th April, the motion was defeated by 163 to 88.

Granville Sharp came up with the idea that the black community in London should be allowed to to start a colony in Sierra Leone. The country was chosen largely on the strength of evidence from the explorer, Mungo Park and a encouraging report from the botanist, Henry Smeathman, who had recently spent three years in the area. The British government supported Sharp's plan and agreed to give £12 per African towards the cost of transport. Sharp contributed more than £1,700 to the venture. In the summer and autumn 1791 Wilberforce worked with his close friend Henry Thornton to launch the company.

Richard S. Reddie, the author of Abolition! The Struggle to Abolish Slavery in the British Colonies (2007) has argued: "Some detractors have since denounced the Sierra Leone project as repatriation by another name. It has been seen as a high-minded yet hypocritical way of ridding the country of its rising black population... Some in Britain wanted Africans to leave because they feared they were corrupting the virtues of the country's white women, while others were tired of seeing them reduced to begging on London streets."

In March 1796, Wilberforce's proposal to abolish the slave trade was defeated in the House of Commons by only four votes. At least a dozen abolitionist MPs were out of town or at the new comic opera in London. Thomas Clarkson commented: "To have all our endeavours blasted by the vote of a single night is both vexatious and discouraging." Wilberforce wrote in his diary: "Enough at the Opera to have carried it. Very much vexed and incensed at our opponents".

William Wilberforce held conservative views on most other issues. He opposed parliamentary reform and supported the suspension of Habeas Corpus that resulted in political activists such as Thomas Hardy and John Thelwall being imprisoned. He also supported the government when it passed Combination Acts of 1799–1800. This made it illegal for workers to join together to press their employers for shorter hours or may pay. As a result trade unions were thus effectively made illegal.

In 1804 Thomas Clarkson returned to his campaign against the slave trade and toured the country on horseback obtaining new evidence and maintaining support for the campaigners in Parliament. A new generation of activists such as Henry Brougham, Zachary Macaulay and James Stephen, helped to galvanize older members of the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

William Wilberforce introduced an abolition bill on 30th May 1804. It passed all stages in the House of Commons and on 28th June it moved to the House of Lords. The Whig leader in the Lords, Lord Grenville, said as so many "friends of abolition had already gone home" the bill would be defeated and advised Wilberforce to leave the vote to the following year. Wilberforce agreed and later commented "that in the House of Lords a bill from the House of Commons is in a destitute and orphan state, unless it has some peer to adopt and take the conduct of it".

In February 1805, Wilberforce presented his eleventh abolition bill to the House of Commons. Charles Brooke reported that the French slave trade was resurgent, so that abolition would merely hand British commerce over to the enemy. Wilberforce replied: "The opportunity now offered may never return, and if the present moment be neglected, events may occur which render the whole of the West India islands one general scene of devastation and horror. The storm is fast gathering; every instant it becomes blacker and blacker. Even now I know not whether it be too late to avert the impending evil, but of this I am quite sure - that we have no time to lose." This time the pro-slave trade MPs were better organised and it was defeated by seven votes.

In February, 1806 Lord Grenville was invited by the king to form a new Whig administration. Grenville, was a strong opponent of the slave trade. Grenville was determined to bring an end to British involvement in the trade. He had spoken against the slave-trade in nearly all the debates in the 1790s. Thomas Clarkson sent a circular to all supporters of the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade claiming that "we have rather more friends in the Cabinet than formerly" and suggested "spontaneous" lobbying of MPs. He added: "There was never perhaps a season when so much virtuous feeling pervading all ranks."

Grenville's Foreign Secretary, Charles Fox, led the campaign in the House of Commons to ban the slave trade in captured colonies. Clarkson commented that Fox was "determined upon the abolition of it (the slave trade) as the highest glory of his administration, and as the greatest earthly blessing which it was the power of the Government to bestow." Wilberforce praised the new, younger, members of Parliament "whose lofty and liberal sentiments... show to the people that their legislators, and especially the higher order of their youth, are forward to assert the rights of the weak against the strong."

This time there was little opposition and the bill was passed by an overwhelming 114 to 15. In the House of Lords Lord Greenville made a passionate speech that lasted three hours where he argued that the trade was "contrary to the principles of justice, humanity and sound policy" and criticised fellow members for "not having abolished the trade long ago". Ellen Gibson Wilson has pointed out: "Lord Grenville ... opposed a delaying inquiry but several last-ditch petitions came from West Indian, London and Liverpool shipping and planting spokesmen.... He was determined to succeed and his canvassing of support had been meticulous." When the vote was taken the bill was passed in the House of Lords by 41 votes to 20.

William Wilberforce now spent his energies developing the Sierra Leone Company as a foundation for disseminating Christianity and civilization in Africa. It has been argued by Stephen Tomkins that during this period "Wilberforce... allowed the abolitionist colony of Sierra Leone... to use slave labour and buy and sell slaves.... After abolition, the British navy patrolled the Atlantic seizing slave ships. The crew were arrested, but what to do with the African captives? With the knowledge and consent of Wilberforce and friends, they were taken to Sierra Leone and put to slave labour in Freetown. They were called 'apprentices', but they were slaves. The governor of Sierra Leone paid the navy a bounty per head, put some of the men to work for the government, and sold the rest to landowners. They did forced labour, under threat of punishment, without pay, and those who escaped to neighbouring African villages to work for wages were arrested and brought back".

In the General Election following the passing of the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act Wilberforce was challenged by a political opponent. He won but the hard contest had left him "thin and old beyond his years". In 1811 he decided to give up the county seat for reasons of health. Lord Calthorpe offered him a pocket borough at Bramber and he was returned from there in 1812 without having to leave his holiday home.

Francis Burdett was a supporter of Wilberforce's campaign against the slave trade. In 1816 he attacked Wilberforce when he refused to complain about the suspension of Habeas Corpus, during the campaign for parliamentary reform. Burdett commented: "How happened it that the honourable and religious member was not shocked at Englishmen being taken up under this act and treated like African slaves?" Wilberforce replied that Burdett was opposing the government in a deliberate scheme to destroy the liberty and happiness of the people.

It gradually became clear that there were serious problems with the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act. British captains who were caught continuing the trade were fined £100 for every slave found on board. However, this law did not stop the British slave trade. In fact, the situation became worse. Now that the supply had officially ceased, the demand grew and with it the price of slaves. For high prices the traders were prepared to take the additional risks. If slave-ships were in danger of being captured by the British navy, captains often reduced the fines they had to pay by ordering the slaves to be thrown into the sea.

Some people involved in the anti-slave trade campaign argued that the only way to end the suffering of the slaves was to make slavery illegal. A new Anti-Slavery Society was formed in 1823 by Thomas Clarkson, Henry Brougham and Thomas Fowell Buxton. "Its purpose was to rouse public opinion to bring as much pressure as possible on parliament, and the new generation realized that for this they still needed Clarkson.... He rode some 10,000 miles and achieved his masterpiece: by the summer of 1824, 777 petitions had been sent to parliament demanding gradual emancipation".

Some people involved in the anti-slave trade campaign such as Thomas Fowell Buxton, argued that the only way to end the suffering of the slaves was to make slavery illegal. "I now regret that I and those honourable friends who thought with me on this subject have not before attempted to put an end, not merely to the evils of the slave trade, but to the evils of slavery itself."

Wilberforce disagreed, he believed that at this time slaves were not ready to be granted their freedom. He pointed out in A Letter on the Abolition of the Slave Trade, Addressed to the Freeholders and other inhabitants of Yorkshire that: "It would be wrong to emancipate (the slaves). To grant freedom to them immediately, would be to insure not only their masters' ruin, but their own. They must (first) be trained and educated for freedom."

In 1823 Wilberforce published his Appeal to the Religion, Justice and Humanity of the Inhabitants of the British Empire in behalf of the Negro Slaves in the West Indies. "In this pamphlet he dwelt on the moral and spiritual degradation of the slaves and presented their emancipation as a matter of national duty to God. It proved to be a powerful inspiration for the anti-slavery agitation in the country."

It also stirred William Cobbett into a virulent published attack on Wilberforce for his alleged failure to acknowledge the extent of the deprivation and oppression suffered by the "free British labourers". Over the years the intensified his attacks on what Cobbett"saw as the hypocrisy of Wilberforce in campaigning for better conditions for Negro slaves abroad while British people lived in desperate conditions at home in the new manufacturing towns".

In 1824 Elizabeth Heyrick published her pamphlet Immediate not Gradual Abolition. In her pamphlet Heyrick argued passionately in favour of the immediate emancipation of the slaves in the British colonies. This differed from the official policy of the Anti-Slavery Society that believed in gradual abolition. She called this "the very masterpiece of satanic policy" and called for a boycott of the sugar produced on slave plantations.

In the pamphlet Heyrick attacked the "slow, cautious, accommodating measures" of the leaders like Wilberforce. "The perpetuation of slavery in our West India colonies is not an abstract question, to be settled between the government and the planters; it is one in which we are all implicated, we are all guilty of supporting and perpetuating slavery. The West Indian planter and the people of this country stand in the same moral relation to each other as the thief and receiver of stolen goods".

The leadership of the organisation attempted to suppress information about the existence of this pamphlet and William Wilberforce gave out instructions for leaders of the movement not to speak on the same platforms as Heyrick and other women who favoured an immediate end to slavery. His biographer, William Hague, claims that Wilberforce was unable to adjust to the idea of women becoming involved in politics "occurring as this did nearly a century before women would be given the vote in Britain".

Although women were allowed to be members they were virtually excluded from its leadership. Wilberforce disliked to militancy of the women and wrote to Thomas Babington protesting that "for ladies to meet, to publish, to go from house to house stirring up petitions - these appear to me proceedings unsuited to the female character as delineated in Scripture".

Thomas Clarkson, another leader of the anti-slavery movement, was much more sympathetic towards women. Unusually for a man of his day, he believed women deserved a full education and a role in public life and admired the way the Quakers allowed women to speak in their meetings. Clarkson told Elizabeth Heyrick's friend, Lucy Townsend, that he objected to the fact that "women are still weighed in a different scale from men... If homage be paid to their beauty, very little is paid to their opinions."

Records show that about ten per cent of the financial supporters of the organisation were women. In some areas, such as Manchester, women made up over a quarter of all subscribers. Lucy Townsend asked Thomas Clarkson how she could contribute in the fight against slavery. He replied that it would be a good idea to establish a women's anti-slavery society.

On 8th April, 1825, Lucy Townsend held a meeting at her home to discuss the issue of the role of women in the anti-slavery movement. Townsend, Elizabeth Heyrick, Mary Lloyd, Sarah Wedgwood, Sophia Sturge and the other women at the meeting decided to form the Birmingham Ladies Society for the Relief of Negro Slaves (later the group changed its name to the Female Society for Birmingham). The group "promoted the sugar boycott, targeting shops as well as shoppers, visiting thousands of homes and distributing pamphlets, calling meetings and drawing petitions."

The society which was, from its foundation, independent of both the national Anti-Slavery Society and of the local men's anti-slavery society. As Clare Midgley has pointed out: "It acted as the hub of a developing national network of female anti-slavery societies, rather than as a local auxiliary. It also had important international connections, and publicity on its activities in Benjamin Lundy's abolitionist periodical The Genius of Universal Emancipation influenced the formation of the first female anti-slavery societies in America".

The formation of other independent women's groups soon followed the setting up of the Female Society for Birmingham. This included groups in Nottingham (Ann Taylor Gilbert), Sheffield (Mary Anne Rawson, Mary Roberts), Leicester (Elizabeth Heyrick, Susanna Watts), Glasgow (Jane Smeal), Norwich (Amelia Opie, Anna Gurney), London (Mary Anne Schimmelpenninck, Mary Foster), Darlington (Elizabeth Pease) and Chelmsford (Anne Knight). Over the next seven years seventy-three of these women's organisations were formed to campaign against slavery.

In 1830, the Female Society for Birmingham submitted a resolution to the National Conference of the Anti-Slavery Society calling for the organisation to campaign for an immediate end to slavery in the British colonies. Elizabeth Heyrick, who was treasurer of the organisation suggested a new strategy to persuade the male leadership to change its mind on this issue. In April 1830 they decided that the group would only give their annual £50 donation to the national anti-slavery society only "when they are willing to give up the word 'gradual' in their title." At the national conference the following month, the Anti-Slavery Society agreed to drop the words "gradual abolition" from its title. It also agreed to support Female Society's plan for a new campaign to bring about immediate abolition.

The Female Society for Birmingham played an important role in the propaganda campaign against slavery. Lucy Townsend, wrote the anti-slavery pamphlet To the Law and to the Testimony (1832). "Under Lucy Townsend's and Mary Lloyd's leadership the society developed the distinctive forms of female anti-slavery activity, involving an emphasis on the sufferings of women under slavery, systematic promotion of abstention from slave-grown sugar through door-to-door canvassing, and the production of innovative forms of propaganda, such as albums containing tracts, poems, and illustrations, embroidered anti-slavery workbags."

William Wilberforce's final decline in health began early in 1833 with a severe attack of influenza. He went to Bath, where the waters had so often in the past appeared beneficial to him, but this time he experienced no relief, suffering "much from pain and languor". In mid-July he was moved to London, where for some days he seemed to improve.

On 26th July, 1833, William Wilberforce received news that the Slavery Abolition Act had passed its third reading. This act gave all slaves in the British Empire their freedom. The British government paid £20 million in compensation to the slave owners. The amount that the plantation owners received depended on the number of slaves that they had. For example, Henry Phillpotts, the Bishop of Exeter, received £12,700 for the 665 slaves he owned.

William Wilberforce died on 29th July 1833 at 44 Cadogan Place, Sloane Street. The following year Robert Wilberforce and Samuel Wilberforce, began work on their father's biography. The book was published in 1838. As Ellen Gibson Wilson, the author of Thomas Clarkson (1989), pointed out: "The five volumes which the Wilberforces published in 1838 vindicated Clarkson's worst fears that he would be forced to reply. How far the memoir was Christian, I must leave to others to decide. That it was unfair to Clarkson is not disputed. Where possible, the authors ignored Clarkson; where they could not they disparaged him. In the whole rambling work, using the thousands of documents available to them, they found no space for anything illustrating the mutual affection and regard between the two great men, or between Wilberforce and Clarkson's brother."

Wilson goes on to argue that the book has completely distorted the history of the campaign against the slave-trade: "The Life has been treated as an authoritative source for 150 years of histories and biographies. It is readily available and cannot be ignored because of the wealth of original material it contains. It has not always been read with the caution it deserves. That its treatment of Clarkson, in particular, a deservedly towering figure in the abolition struggle, is invalidated by untruths, omissions and misrepresentations of his motives and his achievements is not understood by later generations, unfamiliar with the jealousy that motivated the holy authors. When all the contemporary shouting had died away, the Life survived to take from Clarkson both his fame and his good name. It left us with the simplistic myth of Wilberforce and his evangelical warriors in a holy crusade".

Eventually, Robert Wilberforce and Samuel Wilberforce apologized for what they had done to Clarkson: "As it is now several years since the conclusion of all differences between us, and we can take a more dispassionate view than formerly of the circumstances of the case, we think ourselves bound to acknowledge that we were in the wrong in the manner in which we treated you in the memoir of our father.... we are conscious that too jealous a regard for what we thought our father's fame, led us to entertain an ungrounded prejudice against you and this led us into a tone of writing which we now acknowledge was practically unjust."

On this day in 1872 Max Beerbohm was born at 57 Palace Gardens Terrace, London His father, Julius Ewald Edward Beerbohm (1810–1892), had come to England in about 1830 and established himself as a successful corn merchant.

In 1885 he entered Charterhouse School. He later wrote: "My delight in having been at Charterhouse was far greater than my delight in being there… I always longed to be grown-up!". Beerbohm began drawing caricatures of his teachers and of public figures, while at school.

Beerbohm met Oscar Wilde in 1888. Wilde's biographer, Richard Ellmann, has claimed: "Beerbohm was quick and clever: Wilde taught him to be languid and preposterous.... Beerbohm admired, learned, and resisted; aware that Wilde was homosexual, and anxious not to to follow him in that direction, he drew back from intimacy. He was to caricature Wilde savagely; this was ungrateful, but it was a form of ingratitude, and of intimacy, into which other followers of Wilde lapsed."

Beerbohm won a place at Merton College in 1890 to study classics. While at university he became friends with Oscar Wilde, Robert Ross, Alfred Douglas and William Rothenstein. He continued with his drawing and in 1892 The Strand Magazine published thirty-six of his caricatures. He later wrote that this success provided "a great, an almost mortal blow to my modesty".

The publisher, John Lane, invited Aubrey Beardsley and his friend, Henry Harland, to produce a new quarterly, called The Yellow Book. The first edition was published in April, 1894. The reviewer in The Times, pointing to the cover that had been produced by Beardsley and wrote of its "repulsiveness and insolence". The drawings by Beardsley created a great deal of controversy and because of this, the first edition of 5000 copies sold out in five days.

John Lane, was pleased with the success of the book and invited Beardsley and his friend, Henry Harland, to produce a new quarterly, called The Yellow Book. The first edition was published in April, 1894. The reviewer in The Times, pointing to the cover that had been produced by Beardsley, wrote of its "repulsiveness and insolence". The drawings by Beardsley created a great deal of controversy and because of this, the first edition of 5,000 copies sold out in five days.

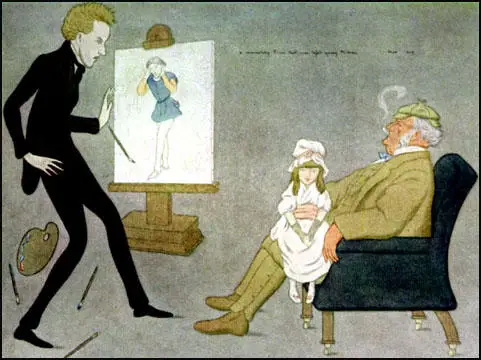

The author of Max Beerbohm: A Kind of Life (2002) has argued: "Max's reputation as a caricaturist was if anything higher than that as an essayist. In the late 1890s his drawing had also developed: it became more subtle, more intricate, more understated, the general softening of tone owing much to the addition of light colour washes, something Will Rothenstein had urged on him. Max himself remarked that as he got older (on into his late twenties) he found that his two arts... were growing more like each other... Max's was one of those rare talents equally distinguished in two arts. His sister arts sometimes come together in those of his drawings with more or less lengthy captions."

Beerbohm's close friend, Oscar Wilde was arrested and charged with offences under the Criminal Law Amendment Act (1885). The trial of Wilde and Alfred Taylor began before Justice Arthur Charles on 26th April, 1895. Of the ten alleged sexual partners Queensberry's plea had named, five were omitted from the Wilde indictment. The trial under Charles ended in jury disagreement after four hours. The second trial, under Justice Alfred Wills, began on 22nd May. Douglas was not called to give evidence at either trial, but his letters to Wilde were entered into evidence, as was his poem, Two Loves. Called on to explain its concluding line - "I am the love that dares not speak its name" Wilde answered that it meant the "affection of an elder for a younger man".

Wilde attempted to defend his relationship with what became known as the "Love that dare not speak its name" speech: "It is that deep, spiritual affection that is as pure as it is perfect. It dictates and pervades great works of art like those of Shakespeare and Michaelangelo, and those two letters of mine, such as they are. It is in this century misunderstood, so much misunderstood that it may be described as the Love that dare not speak its name, and on account of it I am placed where I am now. It is beautiful, it is fine, it is the noblest form of affection. There is nothing unnatural about it. It is intellectual, and it repeatedly exists between an elder and a younger man, when the elder man has intellect, and the younger man has all the joy, hope and glamour of life before him. That it should be so the world does not understand. The world mocks at it and sometimes puts one in the pillory for it."

Max Beerbohm, was in court at the time and wrote to his friend, Reginald Turner: "Oscar has been quite superb. His speech about the Love that dares not tell his name was simply wonderful and carried the whole court right away, quite a tremendous burst of applause. Here was this man, who had been for a month in prison and loaded with insults and crushed and buffeted, perfectly self-possessed, dominating the Old Bailey with his fine presence and musical voice. He has never had so great a triumph, I am sure as when the gallery burst into applause - I am sure it affected the jury."

Beardsley invited Beerbohm to contribute essays and caricatures to the journal. He also wrote for other publications, and he drew caricatures for Pick-Me-Up, Sketch, and the Pall Mall Budget. He also published, under the imprint of The Bodley Head, a collection of essays, entitled The Works of Max Beerbohm (1896). Leonard Smithers, who was a thirty-four-year-old ex-solicitor who sold old books, prints, and pornography from a shop in Arundel Street, off the Strand, published a collection of his drawings, Caricatures of Twenty-Five Gentlemen (1896).

Beerbohm became very close to William Rothenstein. He later wrote: "He (Rothenstein) wore spectacles that flashed that flashed more than any other pair ever seen. He was a wit. He was brimful of ideas... He knew everyone in Paris. He knew them all by heart. He was Paris in Oxford... I liked Rothenstein not less than I feared him; and there arose between us a friendship that has grown ever warmer, and been more and more valued by me, with every passing year."

Beerbohm, whose elder half-brother, Herbert Beerbohm Tree, was one of London's foremost actor–managers, took a keen interest in the theatre. Frank Harris appointed Beerbohm as the drama critic of The Fortnightly Review. In 1898 he began to write a regular column for The Saturday Review, a journal recently purchased by Harris. He held the post for the next twelve years.

Beerbohm was a great supporter of the work of George Bernard Shaw. Although he did not share Shaw's socialist beliefs, described him as "the most brilliant and remarkable journalist in London." He also considered him a great playwright. He was especially complimentary about Man and Superman (1902), which he considered to be his "masterpiece so far". He described it as the "most complete expression of the most distinct personality in current literature".

He also liked John Bull's Other Island (1904): "Mr Shaw, it is insisted, cannot draw life: he can only distort it. All his characters are but so many incarnations of himself. Above all, he cannot write plays. He has no dramatic instinct, no theatrical technique... That theory might have held water in the days before Mr Shaw's plays were acted. Indeed, I was in the habit of propounding it myself... When I saw John Bull's Other Island I found that as a piece of theatrical construction it was perfect... to deny that he is a dramatist merely because he chooses for the most part, to get drama out of contrasted types of character and thought, without action, and without appeal to the emotions, seems to me both unjust and absurd. His technique is peculiar because his purpose is peculiar. But it is not the less technique."

After a series of failed relationships Beerbohm married an American actress, Florence Kahn on 4th May 1910, at the Paddington register office. Enid Bagnold saw them together just after they got married: "She wore her bracelets outside her black net gloves. I was thrilled by the way the top of Max's head steamed in a spiral." William Rothenstein commented: "Max supports matrimony with a charm and grace which is the despair of other husbands."

Beerbohm's biographer, N. John Hall, has pointed out: "He quit his post at the Saturday Review, and went to live the rest of his life in the Villino Chiaro, a small house on the coast road overlooking the Mediterranean at Rapallo, Italy. Max and his wife seem to have had a thoroughly happy life together. There has been speculation that he was a non-active homosexual, that his marriage was never consummated, that he was a natural celibate. The fact is, not much is known of Max's private life."

Beerbohm did over forty caricatures of George Bernard Shaw during his lifetime. He did not find Shaw's appearance attractive. He mentioned his pallid pitted skin and red hair like seaweed. "The back of his neck was especially bleak; very long, untenanted, and dead white". He admitted that Shaw's political views did not help: "My admiration for his genius has during fifty years and more been marred for me by dissent from almost any view that he holds about anything."

Beerbohm held an exhibition of his work at the Leicester Galleries in April 1911. The Times, reviewing the show, claimed that he deserved the title of "the greatest of English comic artists". Beerbohm later defined caricatures as "the delicious art of exaggerating, without fear or favour, the peculiarities of this or that human body, for the mere sake of exaggeration... The whole man must be melted down, as in a crucible, and then, as from the solution, be fashioned anew. He must emerge with not one particle of himself lost, yet with not a particle of himself as it was before."

Beerbohm told William Rothenstein that he was partly responsible for his success: "As you will know, your belief in me has always been a great incentive to me to believe in myself; and your creative, suggestive, fertilizing mind has enormously helped me from time to time. I remember, for example, that it was you who, at Oxford, first told me that I ought to try washes of water-colour - things of which at that time I supposed myself to be quite incapable at the age of ninety. And it was you who made me see the difference between line-y drawing and drawing that had an unjournalistic grace. And it was you, later, whose advice helped me to keep within my own little spiritual way of expression and not to try for external accuracies. And - but I won't enumerate the heaps of ways in which, to me, as to many other more important persons, you have been ballast and inspiration."

In 1911 Max Beerbohm published to great critical acclaim his only novel, Zuleika Dobson. It has often featured in the list of the 100 best novels ever published. This was followed by a collection of seventeen parodies of contemporary writers, A Christmas Garland (1912). The Saturday Review claimed that "He (Beerbohm) has not only parodied the style of his authors, but their minds also".

In February 1914 Frank Harris was sent to Brixton Prison for contempt of court following an article on Earl Fitzwilliam, who had been cited as a co-respondent in a divorce case. His assistant editor, Enid Bagnold, went around to Beerbohm's flat to ask for his help. "I rung his doorbell, and sent up a message as urgent as I could make it by the maid. He was not dressed, but came down in a wonderful dressing-gown, and as he listened his two very blue eyes were serious with anger, though his eyebrows, his mouth, and the rest of his charming face would not go any great lengths. He was angry enough to dress very quickly, and came with me, carrying his cane."

As well as helping editing Modern Society, that week he drew a cartoon for the front cover. It showed Beerbohm having dinner with Harris. Underneath he wrote: "The Best Talker in London, with one of his best listeners".

Beerbohm's next book, Seven Men (1919), was a collection of short stories. One of his greatest fans was Virginia Woolf. She wrote to Beerbohm: "If you knew how I had pored over your essays - how they fill me with marvel - how I can't conceive what it would be like to write as you do!" Beerbohm himself was greatly influenced by the work of Henry James. He told Frank Harris that he "gets effects through those elaborate sentences that you could hardly get otherwise."

Beerholm had further exhibitions at the Leicester Galleries in 1923 and 1925. The New York Herald Tribune published a review which argued: "In terms of aesthetics Mr Beerbohm is not a draughtsman at all; he has a delicate sense of color, decorative felicity… but he has never learned to draw… For his own purposes, however, his drawing is consummate… He has a genius for likenesses; better than anyone else he understands how to convey the attitudes of his subject… Add to these humor without venom and refined imagination and you have lifted caricature into the realm of art."

Beerholm drew caricatures of Oscar Wilde, William Rothenstein, George Bernard Shaw, Thomas Hardy, W. B. Yeats, Lytton Strachey, John Ruskin, William Morris, Aubrey Beardsley, John Singer Sargent, Augustus John, William Gladstone, Benjamin Disraeli, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Henry James, Joseph Conrad, James Whistler, George Meredith, Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, Queen Victoria, Edward VII, George V and Edward VIII. In 1930 he gave up caricaturing: "I found that my caricatures were becoming likenesses. I seem to have mislaid my gift for dispraise. Pity crept in. So I gave up caricaturing, except privately".

In 1939 George VI offered him a knighthood. To the surprise of his friends he accepted the honour. After the ceremony, he wrote to a friend: "My costume yesterday was quite all right… Indeed, I was (or so I thought, as I looked around me) the best-dressed of the Knights, and quite on a level with the Grooms of the Chamber and other palace officials. I'm not sure that I wasn't as presentable as the King himself - very charming though he looked."

After the death of his wife in 1951, Elisabeth Jungmann, became his secretary and companion. He married her just before his death at Rapallo on 20th May 1956.

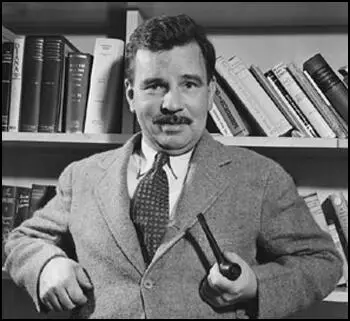

On this day in 1898 Malcolm Cowley, the only child of a homeopathic physician, was born in Cambria County, Pennsylvania. A successful school student, Cowley won a scholarship to Harvard University in 1915. While at university Cowley contributed to the Harvard Advocate and attended lectures by Amy Lowell.

In 1917 Cowley left Harvard to drive munitions trucks for the American Field Service in France. While on the Western Front Cowley wrote articles about the First World War for The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

Cowley returned to the United States in 1918 and soon afterwards met the artist, Peggy Baird. She was briefly married to Orrick Johns but after a visit to Europe she left him and settled in New York City where she mixed with a group of radicals that lived in Greenwich Village. This included Michael Gold, Dorothy Day and Eugene O'Neill. Cowley married Peggy in 1919. He continued with his studies and graduated from Harvard in 1920. For the next few years he wrote poetry and book reviews for The Dial and the New York Evening Post.

In 1921 Cowley moved to France and continued his studies at the University of Montpellier. He also found work with avant-garde literary magazines such as Broom and Secession. While in France he became friendly with American expatriates such as Gertrude Stein, Ernest Hemingway and Ezra Pound.

Cowley returned to the United States in August 1923 and went to live in Greenwich Village where he became close friends with the poet Hart Crane. As well as writing poetry Cowley found work as an advertising copywriter with Sweet's Architectural Catalogue. He also translated seven books from French into English.

In 1929 Cowley published Blue Juniata, his first book of poems. Later that year he replaced Edmund Wilson as literary editor of the New Republic. Cowley's marriage broke up in 1931 and Peggy Baird went to live with Hart Crane in Mexico. This ended in tragedy when Crane committed suicide by jumping from the ship Orizaba on the way back to New York City on 27th April 1932. Two months later Cowley married Muriel Maurer.

Coming under the influence of Theodore Dreiser, Cowley became increasingly involved in radical politics. In 1932 Cowley joined Mary Heaton Vorse, Edmund Wilson and Waldo Frank as union-sponsored observers of the miners' strikes in Kentucky. The men's lives were threatened by the mine owners and Frank was badly beaten up. The following year Cowley published Exile's Return in 1933. The book was largely ignored and sold only 800 copies in the first twelve months. The following year he published an autobiography, The Dream of Golden Mountains (1934).

In 1935 Cowley and other left-wing writers established the League of American Writers. Other members included Erskine Caldwell, Archibald MacLeish, Upton Sinclair, Clifford Odets, Langston Hughes, Carl Sandburg, Carl Van Doren, Waldo Frank, David Ogden Stewart, John Dos Passos, Lillian Hellman and Dashiell Hammett. Cowley was appointed vice president and over the next few years Cowley was involved in several campaigns, including attempts to persuade the United States government to support the republicans in the Spanish Civil War. However, he resigned in 1940 because he felt the organization was under the control of the American Communist Party.

In 1941 President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Archibald MacLeish as head of the Office of Facts and Figures. MacLeish recruited Cowley as his deputy. This decision soon resulted in right-wing journalists such as Whittaker Chambers and Westbrook Pegler writing articles pointing out Cowley's left-wing past. One member of Congress, Martin Dies of Texas, accused Cowley of having connections to 72 communist or communist-front organizations.

MacLeish came under pressure from J. Edgar Hoover, head of the FBI, to sack Cowley. In January 1942, MacLeish replied that the FBI agents needed a course of instruction in history. "Don't you think it would be a good thing if all investigators could be made to understand that Liberalism is not only not a crime but actually the attitude of the President of the United States and the greater part of his Administration?" In March 1942 Cowley, vowing never again to write about politics, resigned from the Office of Facts and Figures.

Cowley now became literary adviser to Viking Press. He now began to edit the selected works of important American writers. Viking Portable editions by Cowley included Ernest Hemingway (1944), William Faulkner (1946) and Nathaniel Hawthorne (1948). In 1949 Cowley returned to the political scene by testifying at the second Alger Hiss trial. His testimony contradicted the main evidence supplied by Whittaker Chambers.

Malcolm Cowley published a revised edition of Exile's Return in 1951. This time the book sold much better. He also published The Literary Tradition (1954) and edited a new edition of Leaves of Grass(1959) by Walt Whitman. This was followed by Black Cargoes, A History of the Atlantic Slave Trade (1962), Fitzgerald and the Jazz Age (1966), Think Back on Us (1967), Collected Poems (1968), Lesson of the Masters (1971) and A Second Flowering (1973).

Malcolm Cowley died on 28th March 1989.

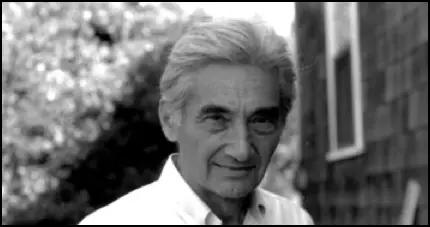

On this day in 1922 Howard Zinn, the son of Jewish immigrants, Edward Zinn, a waiter, and Jennie (Rabinowitz) Zinn, a housewife, was born in Brooklyn in 1922. Zinn later recalled: “We moved a lot, one step ahead of the landlord. I lived in all of Brooklyn’s best slums.”

Zinn attended New York City public schools and after graduating from Thomas Jefferson High School he became a pipe fitter in the Brooklyn Navy Yard where he met his future wife, Roslyn Shechter.

Zinn became very active in left-wing politics and in 1939 he attended a meeting organised by the American Communist Party. "Suddenly, I heard the sirens sound, and I looked around and saw the policemen on horses galloping into the crowd and beating people. I couldn't believe that. And then I was hit. I turned around and I was knocked unconscious. I woke up sometime later in a doorway, with Times Square quiet again, eerie, dreamlike, as if nothing had transpired. I was ferociously indignant... It was a very shocking lesson for me."

A strong opponent of fascism Zinn joined the United States Air Force in 1943. During the Second World War Zinn flew missions throughout Europe. He was awarded the Air Medal, and attained the rank of second lieutenant. In April 1945, he was involved in the bombing of German soldiers based in Royan. "Twelve hundred heavy bombers, and I was in one of them, flew over this little town of Royan and dropped napalm - first use of napalm in the European theater. And we don’t know how many people were killed or how many people were terribly burned as a result of what we did." This experience turned him into an anti-war campaigner.

After the war, Zinn worked at a series of menial jobs until entering New York University on the GI Bill in 1949. He received his bachelor’s degree from NYU, followed by master’s and doctoral degrees in history from Columbia University, where he studied under Henry Steele Commager and Richard Hofstadter. He obtained his PhD with a dissertation about the career of Fiorello LaGuardia. This became the subject of his first book, LaGuardia in Congress (1959). The book was well-received and won the American Historical Association's Albert J. Beveridge Prize.

In 1956, he became the chairmanship of the history and social sciences department at Spelman College, an all-black women's school in Atlanta. Zinn made no attempt to hide his political views. One of his students, Alice Walker, remembers how in his first lecture he stated: “Well, I stand to the left of Mao Zedong.” As she pointed out: "It was such a moment, because the people couldn’t imagine anyone in Atlanta saying something like that, when at that time the Chinese and the Chinese Revolution just meant that, you know, people were on the planet who were just going straight ahead, a folk revolution. So he was saying he was to the left of that."

While teaching at the college he joined the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People and during the 1960s was active in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. His political activities resulted in him losing his job at Spelman College. In 1963, Spelman fired him for "insubordination." Alice Walker argued: "He was thrown out because he loved us, and he showed that love by just being with us. He loved his students. He didn’t see why we should be second-class citizens. He didn’t see why we shouldn’t be able to eat where we wanted to and sleep where we wanted to and be with the people we wanted to be with. And so, he was with us. He didn’t stay back, you know, in his tower there at the school. And so, he was a subversive in that situation."

According to the Los Angeles Times: "During the civil rights movement, Zinn encouraged his students to request books from the segregated public libraries and helped coordinate sit-ins at downtown cafeterias. Zinn also published several articles, including a then-rare attack on the Kennedy administration for being too slow to protect blacks."

In 1964 Howard Zinn became Professor of History at Boston University. Soon afterwards he published his second book, SNCC: The New Abolitionists (1964). This was followed by The Southern Mystique (1964) and New Deal Thought (1966).

Zinn was also one of the leaders of the Anti-Vietnam War protests during the presidencies of Lyndon Baines Johnson and Richard Nixon. When Daniel Ellsberg, an administration official, came out against the war, he gave one copy of the Pentagon Papers Zinn and his wife, Roslyn. As a result of his political activities that he published Vietnam: The Logic of Withdrawal (1967) and Disobedience and Democracy (1968). Zinn travelled to Hanoi with Father Daniel Berrigan and successfully negotiated the release of three captured US airmen.

Zinn came into conflict with John Silber, the president of Boston University. Zinn twice helped lead faculty votes to oust Silber president, who in turn claimed that Zinn was a prime example of teachers "who poison the well of academe." Zinn was also co-chairman of the strike committee when university professors walked out in 1979. After the strike was settled, he and four colleagues were charged with violating their contract when they refused to cross a picket line of striking secretaries. The charges against "the Boston Five" were soon dropped.

George Binette was one of his students: "At first I found his lectures disorganised, bordering on the chaotic. But I soon came to appreciate that through subtly weaving considerable erudition with personal reminiscence, he was challenging the received and often cherished assumptions about US history among young people. In person Zinn frequently projected a Zen-like calm. He seemed to possess exceptional patience, both for naive admirers and stridently reactionary critics, though he never concealed a zealous passion against injustice. And in contrast to many left-leaning academics, he combined his classroom stance with practical action."

Other books by Zinn included The Politics of History (1970), Postwar America (1973), Justice in Everyday Life (1974). A People's History of the United States was published in 1980 with a first printing of 5,000. However, over the next twenty years it achieved sales of over a million copies. Traditional historians criticised the book but as Zinn pointed out: "There's no such thing as a whole story; every story is incomplete. My idea was the orthodox viewpoint has already been done a thousand times." Noam Chomsky has argued that the book had a tremendous impact on the public: "I can't think of anyone who had such a powerful and benign influence... His historical work changed the way millions of people saw the past."

The book was criticised by liberal and conservative historians. When reviewing the book for the New York Times, the historian, Eric Foner described it as "a deeply pessimistic vision of the American experience" and pointed out that "blacks, Indians, women and labourers appear either as rebels or as victims. Less dramatic but more typical lives - people struggling to survive with dignity in difficult circumstances - receive little attention."

Sean Wilentz, a professor of history at Princeton University, had mixed views on Zinn: “What Zinn did was bring history writing out of the academy, and he undid much of the frankly biased and prejudiced views that came before it. But he’s a popularizer, and his view of history is topsy-turvy, turning old villains into heroes, and after a while the glow gets unreal.”

As he wrote in his autobiography, You Can't Be Neutral on a Moving Train (1994), "From the start, my teaching was infused with my own history. I would try to be fair to other points of view, but I wanted more than 'objectivity'; I wanted students to leave my classes not just better informed, but more prepared to relinquish the safety of silence, more prepared to speak up, to act against injustice wherever they saw it. This, of course, was a recipe for trouble."

In 1988, Howard Zinn took early retirement to concentrate on writing. This including a play about the anarchist leader Emma Goldman. Other books by Zinn include: Declarations of Independence (1990), Zinn Reader (1997), Howard Zinn on History (2001), Zinn on War (2001), Terrorism and War (2002), Emma, a biography of Emma Goldman (2002), Disobedience and Democracy (2002), his autobiography, You Can't Be Neutral on a Moving Train (2002), A Power Governments Cannot Suppress (2006), A Young People's History of the United States (2007) and The Unraveling of the Bush Presidency (2007).

Howard Zinn continued to be active in politics and was highly critical of US troops being used in Iraq and Afghanistan. Zinn argued: "Where progress has been made, wherever any kind of injustice has been overturned, it's been because people acted as citizens, and not as politicians. They didn't just moan. They worked, they acted, they organised, they rioted if necessary to bring their situation to the attention of people in power. And that's what we have to do today."

Howard Zinn died of a heart attack while swimming on 27th January, 2010.

On this day in 1943 philosopher Simone Weil died of a combination of tuberculosis and anorexia.

Simone Weil, the daughter of a doctor, was born in Paris, France, in 1909. A member of a prosperous Jewish family Weil studied at the Lycée Fénelon (1920-24), Lycée Victor Duruy (1924-25) and Lycée Hebri IV (1925-28) before entering the Ecole Normale Supérieure in 1928.

At university Weil developed radical political views and was known as the 'Red Virgin'. After graduating she taught at schools in Le Puy, Auxeterre, Roanne, Bourges and Saint-Quentin. Weil also worked as a factory worker for Renault in order to discover what it was like to be a member of the working class. She also served as a volunteer with the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War.

During the Second World War the Weil family left Paris and went to live in Marseilles before moving to the United States. Weil moved to London in November 1942, where he joined General D and his government in exile. She wanted to return to the front-line but because of her poor health she worked for the minister of the interior preparing for the postwar social reconstruction of France.

Simone Weil died of a combination of tuberculosis and anorexia on 24th August 1943. Her writings published after her death included Gravity and Grace (1952) and The Need for Roots (1952).

On this day in 1983 Scott Nearing died in Harborside, Maine.

Scott Nearing was born in Morris Run, Pennsylvania, on 6th August, 1883. While at the University of Pennsylvania, Nearing became a socialist and pacifist.

He graduated in 1909 and worked as a university lecturer but was fired from the University of Pennsylvania (1915) and Toledo University (1917) for his opposition to United States involvement in the First World War. Later Nearing found work teaching at Rand School.

Nearing was active in the campaign for black civil rights and wrote two books on racism, Black America (1924) and Free Born (1932).

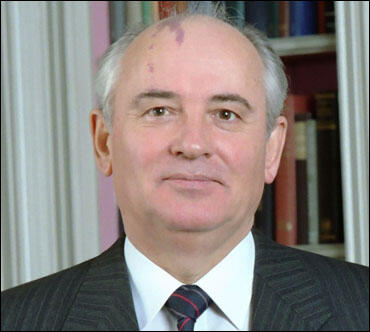

On this day in 1991 Mikhail Gorbachev resigns as head of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

Mikhail Gorbachev, the son of an agricultural mechanic on a collective farm, was born in Privolnoye in the Soviet Union on 2nd March, 1931.

Gorbachev's grandfather, Pantelei Yefimovich Gopkalo, was a staunch member of the Communist Party (CPSU) and was chairman of the village kolkhoz. In 1937 he was arrested by the NKVD Secret Police and charged with being a leader of an underground organization supporting Leon Trotsky. After enduring nearly two years of torture and imprisonment, his grandfather was released in December 1938.

In his memoirs Gorbachev argues this incident had a dramatic impact on his political development. His grandfather remained a committed communist and introduced his grandson to the works of Karl Marx, Frederick Engels and Lenin (although not Leon Trotsky).

During the Second World War Gorbachev's village was occupied by the German Army. He later wrote: "I was fourteen when the war ended. Our generation is the generation of wartime children. It has burned us, leaving its mark both on our characters and in our view of the world."

Gorbachev worked as a combine harvest operator before studying law at Moscow University. While a student Gorbachev joined Communist Party (CPSU) and married Raisa Titorenko.

After leaving university Gorbachev became a full-time official with Komsomol (Communist Youth Organization). In 1955 Gorbachev he was appointed first secretary of the Komsomol Territorial Committee. Gorbachev made rapid progress and by 1960 he was the top Komsomol official in Stavropol. The following year he was a delegate from Stavropol to the 22nd Communist Party Congress in Moscow.

Gorbachev studied for a second degree at the Stavropol Agricultural Institute (1964-67) and in 1970 was appointed First Secretary for Stavropol Territory. His work in this post impressed Yuri Andropov, who was at that time the head of the Committee for State Security (KGB). Andropov now used his considerable influence to promote Gorbachev's career.

In 1971 Gorbachev became a member of Communist Party Central Committee. He later moved to Moscow where he became the Secretary of Agriculture. In 1980 Gorbachev became the youngest member of the Politburo and within four years had become deputy to Konstantin Chernenko.

On the death of Chernenko in 1985 Gorbachev was elected by the Central Committee as General Secretary of the Communist Party. As party leader he immediately began forcing more conservative members of the Central Committee to resign. He replaced them with younger men who shared his vision of reform.

In 1985 Gorbachev introduced a major campaign against corruption and alcoholism. He also spoke about the need for Perestroika (Restructuring) and this heralded a series of liberalizing economic, political and cultural reforms which had the aim of making the Soviet economy more efficient.

Gorbachev introduced policies with the intention of establishing a market economy by encouraging the private ownership of Soviet industry and agriculture. However, the Soviet authoritarian structures ensured these reforms were ineffective and there were shortages of goods available in shops.

Gorbachev also announced changes to Soviet foreign policy. In 1987 he met with Ronald Reagan and signed the Immediate Nuclear Forces (INF) abolition treaty. He also made it clear he would no longer interfere in the domestic policies of other countries in Eastern Europe and announced the withdrawal of Soviet forces from Afghanistan. In December 1987 he announced the withdrawal of 500,000 Soviet troops from Central and Eastern Europe and made it clear he would not send in Soviet troops to protect communist states. The following year he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

Aware that Gorbachev would not send in Soviet tanks there were demonstrations against communist governments throughout Eastern Europe. Over the next few months the communists were ousted from power in Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania, and East Germany.

Gorbachev's attempts to make the Soviet Union a more democratic country made him unpopular with conservatives still in positions of power. In August 1991 he survived a coup staged by hard-liners in the Communist Party.

Gorbachev responded by dissolving the Central Committee. However, with the Soviet Union disintegrating into separate states, Gorbachev resigned from office on 25th December, 1995.