On this day on 23rd November

On this day in 1499 Perkin Warbeck was hanged at Tyburn. Warbeck was born in Tournai in about 1474. According to his biographer, S. J. Gunn: "His parents can be identified as Jehan de Werbecque and Nicaise Farou, members of Tournai's prosperous class of leading artisans, small merchants, and civic officials. Warbeck's early experiences were cosmopolitan. In 1484–7 he was in Antwerp, Bergen op Zoom, and Middelburg, completing his education by learning Flemish and working for merchants, probably in the cloth trade. In April–May 1487 he moved on to the Portuguese court in the company of Lady Margaret Beaumont, wife of the Anglo-Portuguese Jewish convert courtier and international trader Sir Edward Brampton. At Lisbon he took service with the royal councillor and explorer Pero Vaz de Cunha, then in 1488 with a Breton merchant, Pregent Meno."

While visiting Cork in December 1491 he was persuaded to impersonate Richard, Duke of York, second son of Edward IV, who had disappeared eight years earlier together with his elder brother, Edward. In 1492 King Charles VIII of France began funding his campaign. This included being sent to Vienna to meet Emperor Maximilian. He gave his support to Perkin Warbeck but spies in the Maximilian's court told Henry VII about the conspiracy. As a result, several people in England were arrested and executed.

In July 1495 Warbeck landed some of his men at Deal. They were quickly rounded up by the Sheriff of Kent and so Warbeck decided to return to Ireland. However, on 20th November 1495 he went to see King James IV of Scotland in Stirling Castle. On 13th January 1496 James arranged for him to marry him to Lady Katherine Gordon, a distant royal relative. He also provided funding for Warbeck's 1,400 supporters. When Henry VII heard what was happening he began to plan an invasion of Scotland.

Henry VII decided he would need to impose a new tax to pay the cost of raising an army. The people of Cornwall objected to paying taxes for war against Scotland and began a march on London. By 13th June, 1496, the Cornishmen, said to number 15,000, were at Guildford. The army of 8,000 that was being prepared against Scotland had to be rapidly diverted to protect London. On 16th June the rebel army reached Blackheath. When they saw Henry's large army, said to now number 25,000, some of them deserted.

Henry VII sent a force of archers and cavalry round the back of the rebels. According to Francis Bacon: "The Cornish, being ill-armed and ill-led and without horse or artillery, were with no great difficulty cut in pieces and put to flight." A large number of the rebels were killed. Some of its leaders were hanged, drawn and quartered. He then proceeded to fine all those involved in the rebellion. It is claimed this raised £14,699. Bacon commented: "The less blood he drew, the more he took of treasure."

Perkin Warbeck decided to take advantage on the Cornish rebellion by landing in Whitesand Bay on 7th September. He quickly recruited 8,000 Cornishmen but they were unsuccessful in taking Exeter. They retreated to Taunton but with news that Henry's army was marching into Cornwall, on 21st September, Warbeck escaped and sought sanctuary at Beaulieu Abbey. However, he was captured and was brought before Henry at Taunton Castle on 5th October. Warbeck was taken to London where he was repeatedly paraded through the city.

Warbeck managed to escape but he was soon recaptured and on 18th June, 1499, he was sent to the Tower of London for life. The following year he became entangled in another plot. "Exactly what part he played in the conspiracy, and in its betrayal to the king on 3 August, is hard to establish, but Henry and his council resolved to punish all the principal participants."

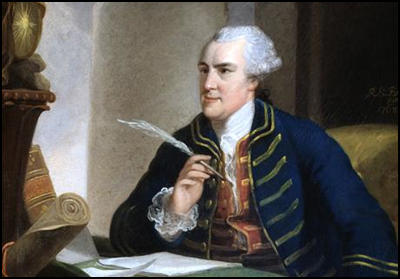

On this day in 1763 Parliament voted that a member's privilege from arrest did not extend to the writing and publishing of seditious libels. In 1762, George III, arranged for his close friend, the Earl of Bute, to become Prime Minister. This decision upset a large number of MPs who considered Bute to be incompetent. John Wilkes, the MP for Aylesbury became Bute's leading critic in the House of Commons. In June 1762 Wilkes established The New Briton, a newspaper that severely attacked the king and his Prime Minister.

After one article that appeared on 23rd April 1763, George III and his ministers decided to prosecute John Wilkes for seditious libel. He was arrested but at a court hearing the Lord Chief Justice ruled that as an MP, Wilkes was protected by privilege from arrest on a charge of libel. However, on 23rd November, 1763, Parliament voted that a member's privilege from arrest did not extend to the writing and publishing of seditious libels. Wilkes escaped to France but in March 1768 he returned to England and stood and won as the Radical candidate for Middlesex.

On 8th June 1768 John Wilkes was found guilty of libel and sentenced to 22 months imprisonment and fined £1,000. Wilkes was also expelled from the House of Commons but in February, March and April, 1769, he was three times re-elected for Middlesex. On all three occasions the decision of the Middlesex electorate was overturned by Parliament. In May the House of Commons voted that Colonel Henry Luttrell, the defeated candidate at Middlesex, should be accepted as the MP.

On 20th February 1769, a lawyer, John Glynn, organised a meeting at the London Tavern to discuss the refusal of the House of Commons to accept the election of John Wilkes. Glynn subscribed £3,340 to form an organisation, the Bill of Rights Society, that would help support the campaign to reinstate Wilkes. Robert Morris, a Welsh barrister, was elected secretary, John Horne Tooke became treasurer. Other members of the group included John Sawbridge, the MP for Hythe, Sir Cecil Wray, MP for East Retford and Sir John Molesworth, MP for Cornwall.

Meetings of the Bill of Rights Society took place fortnightly at the London Tavern. At first the main objective of the society was to "maintain and defend the liberty of the subject, and to support the laws and constitution of the country." John Horne Tooke, who eventually became the most important figure in the Society, believed that the organisation should campaign for a radical programme of parliamentary reform. Tooke managed to do this but some members disagreed and it was this conflict that eventually brought the Bill of Rights Society to an end in 1771.

On this day in 1875 Katharine Symonds, the daughter of the historian, John Addington Symonds and Janet Catherine, was born. Educated by governesses and her mother she spent most of her early life in Switzerland and Italy.

Katharine had intended to train as a hospital nurse but after meeting the artist, Charles Wellington Furse, she changed her plans. The couple were married in 1900 but Furse died four years later leaving her with two young children.

In 1909 Katharine Furse joined the Red Cross Voluntary Aid Detachment that was attached to the Territorial Army. On the outbreak of the First World War Furse was chosen to head the first Voluntary Aid Detachment unit to be sent to France. Aware of her administrative abilities, the authorities decided to place Furse in charge of the VAD Department in London. By 1916 she was appointed Commander-in-Chief and the following year became one of the five women appointed Dame Grand Cross, a newly created Order of the British Empire.

Although considered a great success as head of the Voluntary Aid Detachment, Furse was unhappy about her lack of power to introduce reforms. In November 1917, Furse and several of her senior colleagues resigned. Furse was immediately offered the post as Director of the Women's Royal Naval Service (WRNS).

The Royal Navy was the first of the armed forces to recruit women and since 1916 the Women's Royal Naval Service took over the role of cooks, clerks, wireless telegraphists, code experts and electricians. The women were so successful that other organizations such as the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) and the Women's Royal Air Force were also established.

After the war Furse joined the travel agency of Sir Henry Lunn. Working mainly in Switzerland, Furse became an expert skier and did a great deal to popularize the sport with British tourists. He achievements were acknowledged when she became President of the Ladies' Ski Club.

In 1920 formed the Association of Wrens and this led to her becoming head of the Sea Rangers and for ten years was director of the World Association of Girl Guides and Girl Scouts. Her autobiography, Hearts and Pomegranates was published in 1940.

Katharine Furse died in London on 25th November, 1952.

On this day in 1876 Maude Royden, the youngest of the eight children of Sir Thomas Bland Royden (1831–1917), was born at Mossley Hill, near Liverpool.

Royden was educated at Cheltenham Ladies' College, and at Lady Margaret Hall. As a result of the contacts she made at Oxford University she developed an interest in the plight of the poor. She decided to leave university to take up work in a Victoria Women's Settlement in Liverpool.

In 1902 she went to work with the Reverend Hudson Shaw (1859–1944) in his parish in South Luffenham. Shaw was leading figure in the Oxford University extension movement. As her biographer, Sheila Fletcher, has pointed out: "She grew strongly attached to Shaw and his mentally fragile wife, Effie, helping them revive a sluggish parish. Finding she had gifts of self-expression far beyond the needs of a Sunday school class, Shaw resolved to get her extension work, lecturing on English literature. Though the Oxford delegacy then employed only male lecturers, he insisted that they try her out. This was her start in public speaking."

Maude Royden became increasingly interested in the subject of women's rights and she joined the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. Working under Millicent Fawcett she soon became one of the organisation's main public speakers. In 1909 she helped form the Church League for Women's Suffrage. Two years later she was elected to the executive committee of the NUWSS. Royden also edited its newspaper, The Common Cause, between 1913-1914.

When the First World War was declared two pacifists, Clifford Allen and Fenner Brockway, formed the No-Conscription Fellowship (NCF), an organisation that encouraged men to refuse war service. The NCF required its members to "refuse from conscientious motives to bear arms because they consider human life to be sacred." As Martin Ceadel, the author of Pacifism in Britain 1914-1945 (1980) pointed out: "Though limiting itself to campaigning against conscription, the N.C.F.'s basis was explicitly pacifist rather than merely voluntarist.... In particular, it proved an efficient information and welfare service for all objectors; although its unresolved internal division over whether its function was to ensure respect for the pacifist conscience or to combat conscription by any means"

Maude Royden was a strong supporter of the No-Conscription Fellowship. The group received support from public figures such as Bertrand Russell, Philip Snowden, Bruce Glasier, Robert Smillie, C. H. Norman, William Mellor, Arthur Ponsonby, Guy Aldred, Alfred Salter, Duncan Grant, Wilfred Wellock, Maude Royden, Max Plowman and Rev. John Clifford. Other members included Cyril Joad, Alfred Mason, Winnie Mason, Alice Wheeldon, William Wheeldon, John S. Clarke, Arthur McManus, Hettie Wheeldon, Storm Jameson, Duncan Grant, Max Plowman and Rev. John Clifford.

After the outbreak of the war Royden found herself in conflict with many in the NUWSS, which under the leadership of Millicent Fawcett, had support the war effort. At the end of 1914 she became the secretary of the Fellowship of Reconciliation. In February 1915 she resigned as editor of The Common Cause and gave up her place on the NUWSS executive council. She now joined the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom.

In 1917 the City Temple, the Congregational church in Holborn, offered her a preaching post. Royden became well known as a speaker on social and religious subjects. In a speech on 16 July 1917 at Queen's Hall , London, she said; "The Church should go forward along the path of progress and be no longer satisfied only to represent the Conservative Party at prayer."

In 1918 she spoke in Hudson Shaw's church on the League of Nations and Christianity. As a result he was rebuked by the Bishop of London. Shaw asked her to preach at the three hours' service on Good Friday (18th April). The bishop forbade it, on the grounds that this was an especially ‘sacred’ service. Soon afterwards, the Church League for Women's Suffrage, resolved to campaign not only for the preaching but the priesthood of women.

In 1921 Maude Royden established the Guildhouse, an ecumenical place of worship and a cultural centre. On Sunday afternoons there were talks about politics and the arts. Royden preached at the Sunday evening service to a congregation from all over London. She became famous and was asked to preach all over the world.

Maude Royden joined the Labour Party and in 1922 she was invited to stand as its candidate for the Wirral constituency but declined because she wanted to concentrate on her religious work. The following year she preached in churches and cathedrals in the USA, where she advocated the Christian cause of peace and the need for the League of Nations. She also went on speaking tours in Japan, China, Australia and New Zealand.

In 1928 Radclyffe Hall published the novel, The Well of Loneliness, about the subject of lesbianism. The publisher, Jonathan Cape, argued on the bookjacket that: "In England hitherto the subject has not been treated frankly outside the regions of scientific text-books, but that its social consequences qualify a broader and more general treatment is likely to be the opinion of thoughtful and cultured people."

There was a campaign by the press to get the book banned. The Sunday Express argued: "In order to prevent the contamination and corruption of English fiction it is the duty of the critic to make it impossible for any other novelist to repeat this outrage. I say deliberately that this novel is not fit to be sold by any bookseller or to be borrowed from any library."

Behind the scenes the Home Office put pressure of Jonathan Cape to withdraw the book. One official described the book as "inherently obscene… it supports a depraved practice and is gravely detrimental to the public interest". The chief magistrate, Sir Chartres Biron, ordered that all copies be destroyed, and that literary merit presented no grounds for defence. The publisher agreed to withdraw the novel and proofs intended for a publisher in France were seized in October 1928.

Maude Royden gave passionate support for the book. A sermon on the subject was published in The Guildhall Monthly in April 1929. "I feel bound to say that I find it difficult to understand why an official who permits the publication of books so filthy that it soils the mind to read them, and the production of plays in which everything that is connected with sex is degraded, in which marriage and adultery alike are treated as though they were rather a nasty joke, should have fastened on this particular book as being unfit for us to read. I do not desire that those other books or plays should be suppressed; I have no faith at all in that way of dealing with evil. It is better to concentrate our efforts on trying to be interested in something that is good than to take a short cut to virtue by repressing what is evil."

Radclyffe Hall wrote to Maude Royden explaining her motivation for writing the novel: "May I take this opportunity of telling you how much your support of The Well of Loneliness has meant to its author during the past months of government persecution. I wrote the book in order to help a very much misunderstood and therefore unfortunate section of society, and to feel that a leader of thought like yourself had extended to me your understanding was, and still is, a source of strength and encouragement."

Martin Ceadel, the author of Pacifism in Britain 1914-1945 (1980) has pointed out: "Indeed what was perhaps the most sanguine pacifist initiative of the entire twentieth century occurred in February 1932: the attempt by a trio of leading Christian pacifists to form a Peace Army of unarmed passive resisters to intercede between the combats in the world's military confrontations, starting with the one in Manchuria. The prime mover of this scheme was one of the inter-war period's best-known woman pacifists, Dr Maude Royden, a former suffragist who... had devoted herself to the cause of peace."

In 1934 she visited India with Margery Corbett Ashby and met Ghandi. However, as Sheila Fletcher has pointed out: "But while she was buoyed up by a sense of mission, the Guildhouse suffered from her absences. Later she regretted having turned increasingly to preaching as hopes of the priesthood faded. In 1936 when the Guildhouse closed, her sense of failure was not assuaged by her being by then a Companion of Honour and holder of honorary doctorates."

In July 1935, Richard Sheppard, a canon of St. Paul's Cathedral, formed the Peace Pledge Union (PPU). Maude Royden along with Arthur Ponsonby, George Lansbury, Vera Brittain, Wilfred Wellock, Siegfried Sassoon, Donald Soper, Aldous Huxley, Laurence Housman and Bertrand Russell, joined this new group. Over the next two years the PPU obtained over 100,000 members.

From 1937 the PPU organized alternative Remembrance Day commemorations, including the wearing of white rather than red poppies on 11th November. In 1938 the PPU campaigned against legislation introduced by Parliament for air raid precautions, and the following year against legislation for military conscription.

On the outbreak of the Second World War Maude Royden renounced pacifism as she accepted that it was necessary to fight against the evils of Nazi Germany. In October 1944 she married the recently widowed Hudson Shaw. He was then eighty-five and died two months later. In her autobiography, A Threefold Cord (1947) she revealed that she had a passionate but platonic love for each other from first meeting in 1901.

Maude Royden died in Hampstead on 30th July 1956.

On this day in 1805 Mary Grant was born in Kingston, Jamaica. Her father was a Scottish army officer and her mother a free black woman who ran a boarding house in Kingston. Mary's mother also treated people who become ill. She was a great believer in the herbal medicines. These medicines were based on the knowledge of slaves brought from Africa. This knowledge was passed on to Mary and later she also become a 'doctress'.

On 10th November 1836 she married, in Kingston, one of her mother's resident guests, Edwin Horatio Seacole, but she was soon widowed. According to her biographer, Alan Palmer: "With her sister, Louisa, she ran the family boarding-house for several years, supervising its reconstruction after Kingston's great fire in 1843. She nursed cases of cholera and yellow fever in Jamaica and at Las Cruces in Panama where, for more than two years, she helped her brother manage a hotel. On returning to Jamaica she was briefly nursing superintendent at Up-Park military camp."

In 1850 Kingston was hit by a cholera epidemic. Mary Seacole, used herbal medicines and other remedies including lead acetate and mercury chloride. She also dealt with a yellow fever outbreak in Jamaica. Her fame as a medical practitioner grew and she was soon carrying out operations on people suffering from knife and gunshot wounds.

Mary loved travelling and as a young woman visited the Bahamas, Haiti and Cuba. In these countries she collected details of how people used local plants and herbs to treat the sick. On one trip to Panama she helped treat people during another cholera epidemic. Mary carried out an autopsy on one victim and was therefore able to learn even more about the way the disease attacked the body.

In 1853 Russia invaded Turkey. Britain and France, concerned about the growing power of Russia, went to Turkey's aid. This conflict became known as the Crimean War. Soon after British soldiers arrived in Turkey, they began going down with cholera and malaria. Within a few weeks an estimated 8,000 men were suffering from these two diseases. At the time, disease was a far greater threat to soldiers than was the enemy. In the Crimean War, of the 21,000 soldiers who died, only 3,000 died from injuries received in battle.

Mary Seacole travelled to London to offer her services to the British Army. There was considerable prejudice against women's involvement in medicine and her offer was rejected. When The Times publicised the fact that a large number of British soldiers were dying of cholera there was a public outcry, and the government was forced to change its mind. Florence Nightingale, who had little practical experience of cholera, was chosen to take a team of thirty-nine nurses to treat the sick soldiers.

Mary Seacole's application to join Florence Nightingale's team was rejected. Mary, who had become a successful business woman in Jamaica, decided to travel to the Crimea at her own expense. She visited Florence Nightingale at her hospital at Scutari. Unwilling to accept defeat, Mary started up a business called the British Hotel but others referred to as “Mrs Seacole’s hut” a few miles from the battlefront. Here she sold food and drink to the British officers and a canteen for the soldiers.

Alan Palmer has argued: "Her independent status ensured a freedom of movement denied the formal nursing service; by June she was a familiar figure at the battle-front, riding forward with two mules in attendance, one carrying medicaments and the other food and wine. She brought medical comfort to the maimed and dying after the assault on the Redan, in which a quarter of the British force was killed or wounded, and she tended Italian, French, and Russian casualties at the Chernaya two months later."

Lady Alicia Blackwood wrote in A Narrative of Personal Experiences and Impressions during a Residence on the Bosphorous throughout the Crimean War (1881): "She (Mary Seacole) had, during the time of battle, and in the time of fearful distress, personally spared no pains and no exertion to visit the field of woe, and minister with her own hands such things as she could comfort, or alleviate the sufferings of those around her; freely giving to such as could not pay, and to many whose eyes were closing in death, from whom payment could never be expected."

William H. Russell, wrote in The Times: "In the hour of their illness, these men have found a kind and successful physician, a Mrs Seacole. She is from Kingston (Jamaica) and she doctors and cures all manner of men with extraordinary success. She is always in attendance near the battlefield to aid the wounded, and has earned many a poor fellow's blessing." However, Lynn MacDonald points out: "The medical treatment she gave to soldiers is easily exaggerated - her patients were all relatively healthy walk-ins. The most serious cases went to the general hospitals, the less serious to the regimental hospitals."

Whereas Florence Nightingale and her nurses were based in a hospital several miles from the front, Mary Seacole treated her patients on the battlefield. On several occasions she was found treating wounded soldiers from both sides while the battle was still going on. However, most of her time on battle days went to selling food and drink to officers and spectators.

After the war ended in 1856 Mary Seacole returned to England where she opened a canteen at Aldershot, a venture that failed through lack of funds. By November she was bankrupt. She was encouraged to write an autobiography, published by Blackwood in July 1857 as the Wonderful Adventures of Mrs Seacole. It sold well and lived in some comfort during her final years. Mary Seacole died of apoplexy in London on 14th May, 1881.

On this day in 1910 Edith Downing of the WSPU was arrested and sentenced to seven days' imprisonment for throwing a stone through a window of Somerset House. Downing was born in Cardiff in 1857. She studied at the Slade School of Fine Art (1892-93) and exhibited at the Royal Academy for the first time in 1892. In 1898 she had two sculptures accepted. Over the next few years she became a regular exhibitor at the academy.

Downing joined the Central Society for Women's Suffrage in 1903 and its successor, London Society for Women's Suffrage in 1906. Downing became frustrated by the lack of success of these organisations and in 1908 she became a member of the Women Social & Political Union. The following year she made small portraits of Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney, that were sold for WSPU funds.

Downing joined forces with Marion Wallace-Dunlop to organise a series of spectacular WSPU processions. The most impressive of these was the Woman's Coronation Procession on 17th June 1911. Flora Drummond led off on horseback with Charlotte Marsh as colour-bearer on foot behind her. She was followed by Marjorie Annan Bryce in armour as Joan of Arc.

The art historian, Lisa Tickner, described the event in her book The Spectacle of Women (1987): "The whole procession gathered itself up and swung along Northumberland Avenue to the strains of Ethel Smyth's March of the Women... The mobilisation of 700 prisoners (or their proxies) dressed in white, with pennons fluttering from their glittering lances, was, as the Daily Mail observed, "a stroke of genius". As The Daily News reported: "Those who dominate the movement have a sense of the dramatic. They know that whereas the sight of one woman struggling with policemen is either comic or miserably pathetic, the imprisonment of dozens is a splendid advertisement."

During the 1910 General Election the NUWSS organised the signing petitions in 290 constituencies. They managed to obtain 280,000 signatures and this was presented to the House of Commons in March 1910. With the support of 36 MPs a new suffrage bill was discussed in Parliament. The WSPU suspended all militant activities and on 23rd July they joined forces with the NUWSS to hold a grand rally in London. When the House of Commons refused to pass the new suffrage bill, the WSPU broke its truce on what became known as Black Friday on 18th November, 1910, when its members clashed with the police in Parliament Square. Edith Downing was one of the women arrested during this demonstration but was released without charge. On 23rd November she was arrested again and sentenced to seven days' imprisonment for throwing a stone through a window of Somerset House.

Christabel Pankhurst decided that the WSPU needed to intensify its window-breaking campaign. On 1st March, 1912, a group of suffragettes volunteered to take action in the West End of London. The Daily Graphic reported the following day: "The West End of London last night was the scene of an unexampled outrage on the part of militant suffragists.... Bands of women paraded Regent Street, Piccadilly, the Strand, Oxford Street and Bond Street, smashing windows with stones and hammers." Edith Downing was arrested for taking part in this demonstration. While in Holloway Prison she took part in the mass hunger strike and was forcibly fed before being released.

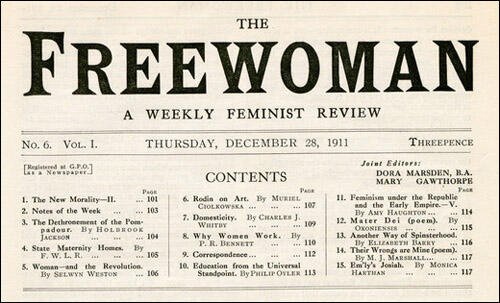

On this day in 1911, the first edition of the feminist journal, The Freewoman appeared. In March 1911 Dora Marsden and her close friend, Grace Jardine, went to work for the Women's Freedom League newspaper, The Vote. Marsden attempted to persuade the WFL to finance a new feminist journal. When this proposal was refused, Marsden left. She now joined forces with Jardine and Mary Gawthorpe to establish her own journal. Charles Granville, agreed to become the publisher. On 23rd November, 1911, they published the first edition of The Freewoman. The journal caused a storm when it advocated free love and encouraged women not to get married. The journal also included articles that suggested communal childcare and co-operative housekeeping.

Mary Humphrey Ward, the leader of Anti-Suffrage League argued that the journal represented "the dark and dangerous side of the Women's Movement". According to Ray Strachey, the leader of the National Union of Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), Millicent Fawcett, read the first edition and "thought it so objectionable and mischievous that she tore it up into small pieces". Whereas Maude Royden described it as a "nauseous publication". Edgar Ansell commented that it was "a disgusting publication... indecent, immoral and filthy."

Other feminists were much more supportive, Ada Nield Chew, argued that the was "meat and drink to the sincere student who is out to learn the truth, however unpalatable that truth may be." Benjamin Tucker commented that it was "the most important publication in existence". Floyd Dell, who worked for the Chicago Evening Post argued that before the arrival of The Freewoman: "I had to lie about the feminist movement. I lied loyally and hopefully, but I could not have held out much longer. Your paper proves that feminism has a future as well as a past." Guy Aldred pointed out: "I think your paper deserves to succeed. I will use my influence in the anarchist movement to this end." Others showed their support for the venture by writing without payment for the journal. This included Teresa Billington-Greig, Rebecca West, H. G. Wells, Edward Carpenter, Havelock Ellis, Stella Browne, C. H. Norman, Edmund Haynes, Catherine Gasquoine Hartley, Huntley Carter, Lily Gair Wilkinson and Rose Witcup.

Edwin Bjorkman, writing in the American Review of Reviews, was a great fan of the writing of Dora Marsden: "The writer of The Freewoman editorials has shot into the literary and philosophical firmament as a star of the first magnitude. Although practically unknown before the advent of The Freewoman ... she speaks always with the quietly authoritative air of the writer who has arrived. Her style has beauty as well as force and clarity."

Marsden also attacked the WSPU's strategy of employing militant tactics. She argued that the autocracy of Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst prevented independent thought and encouraged followers to become "bondwomen". Marsden went on to suggest "the paramount interest of the WSPU was neither the emancipation of women, nor the vote, but the increase in power of their own organisation." On 7th March, 1912, she wrote: "The Pankhurst party have lost their forthright desire for enfranchisement in their outbalancing desire to raise their own organisation to a position of dictatorship amongst all women's organisations.... The vote was only of secondary importance to the leaders... before every other consideration, political, social or moral comes the aggrandisement of the WSPU itself and the increase of power of their own organisation."

The most controversial aspect of the The Freewoman was its support for free-love. On 23rd November, 1911 Rebecca West wrote an article where she claimed: "Marriage had certain commercial advantages. By it the man secures the exclusive right to the woman's body and by it, the woman binds the man to support her during the rest of her life... a more disgraceful bargain was never struck."

On 28th December 1911, Dora Marsden began a five-part series on morality. Dora argued that in the past women had been encouraged to restrain their senses and passion for life while "dutifully keeping alive and reproducing the species". She criticised the suffrage movement for encouraging the image of "female purity" and the "chaste ideal". Dora suggested that this had to be broken if women were to be free to lead an independent life. She made it clear that she was not demanding sexual promiscuity for "to anyone who has ever got any meaning out of sexual passion the aggravated emphasis which is bestowed upon physical sexual intercourse is more absurd than wicked."

Dora Marsden went on to attack traditional marriage: "Monogamy was always based upon the intellectual apathy and insensitiveness of married women, who fulfilled their own ideal at the expense of the spinster and the prostitute." According to Marsden monogamy's four cornerstones were "men's hypocrisy, the spinster's dumb resignation, the prostitute's unsightly degradation and the married woman's monopoly." Marsden then added "indissoluble monogamy is blunderingly stupid, and reacts immorally, producing deceit, sensuality, vice, promiscuity and an unfair monopoly." Friends assumed that Marsden was writing about her relationships with Grace Jardine and Mary Gawthorpe.

Dora argued that it would be better if women had a series of monogamous relationships. Les Garner, the author of A Brave and Beautiful Spirit (1990) has argued: "How far her views were based on her own experience it is difficult to tell. Yet the notion of a passionate but not necessarily sexual relationship would perhaps adequately describe her friendship with Mary Gawthorpe, if not others too. Certainly, her argument would appeal to single women like herself who had sexual desires and feelings but were not allowed to express them - unless, of course, in marriage. Even then, sex, for women at least, was supposed to be reserved for procreation."

On 21st March 1912 Stella Browne wrote about her views on free-love in The Freewoman: "The sexual experience is the right of every human being not hopelessly afflicted in mind or body and should be entirely a matter of free choice and personal preference untainted by bargain or compulsion." According to her biographer, Lesley A. Hall: "Browne emphasized the need for women to speak about their own experiences. In both principle and practice Stella was a convinced believer in free love, known to have had various lovers, certainly some male, and possibly some female, though these cannot be reliably identified."

Charlotte Payne-Townshend Shaw, the wife of George Bernard Shaw, wrote to Dora Marsden "though there has been much I have not agreed with in the paper", The Freewoman was nevertheless a "valuable medium of self-expression for a clever set of young men and women". However, Olive Schreiner disagreed and argued that the debates about sexuality were inappropriate and revolting in a publication of "the women's movement". Frank Watts wrote a letter to the journal that if women really wanted to discuss sex "then it must be admitted by sane observers that man in the past was exercising a sure instinct in keeping his spouse and girl children within the sheltered walls of ignorance."

Harry J. Birnstingl praised Marsden for raising the subject of homosexuality. He added: "It apparently has never occurred to them that numbers of these women find their ultimate destiny, as it were, among members of their own sex, working for the good of each other, forming romantic - nay passionate - attachments with each other? It is splendid that these women... should suddenly find their destiny in thus working together for the freedom of their own sex. It is one of the most wonderful things of the twentieth century."

The articles on sexuality created a great deal of controversy. However, they were very popular with the readers of the journal. In February 1912, Ethel Bradshaw, secretary of the Bristol branch of the Fabian Women's Group, suggested that readers formed Freewoman Discussion Circles. Soon afterwards they had their first meeting in London and other branches were set up in other towns and cities.

Some of the talks that took place in the Freewoman Discussion Circles included Edith Ellis (Some Problems of Eugenics), Rona Robinson (Abolition of Domestic Drudgery), C. H. Norman (The New Prostitution), Edmund Haynes (Divorce Reform), Huntley Carter (The Dances of the Stars) and Guy Aldred (Sex Oppression and the Way Out). Other active members included Grace Jardine, Stella Browne, Harry J. Birnstingl, Charlotte Payne-Townshend Shaw, Rebecca West, Havelock Ellis, Lily Gair Wilkinson, Françoise Lafitte-Cyon and Rose Witcup.

Harriet Shaw Weaver was one of those who joined the Freewoman Discussion Circle in London. The authors of Dear Miss Weaver (1970) pointed out: "It was a successful group, inaugurated at a meeting of more than eighty people. The numbers increased so fast that at its first meeting-room, at the Suffragette shop, was too small. So was its second, at the Eustace Miles vegetarian restaurant; and its final home was at the Chandos Hall. The programme for the session July to October 1912 included talks on Eugenics by Mrs Havelock Ellis and on Divorce Reform by E.S.P. Haynes. Other subjects were Sex Oppression and the Way Out, Celibacy, Prostitution, and the Abolition of Domestic Drudgery." Rebecca West recalled that at the meetings: "Everyone behaved beautifully - it's like being in Church, except Rona Robinson and myself. Barbara Low has spoken very seriously to me about it."

In July 1912, The Morning Post carried a letter from Lord Eustace Percy condemning The Freewoman as an immoral paper. Charles Granville replied that "The Freewoman's work was to clense the gutters of our national existence, gutters which, at present, are an offensive stench in the nostrils of God."

By the summer of 1912 Dora Marsden had become disillusioned with the parliamentary system and no longer considered it important to demand women's suffrage: "The politics of the community are a mere superstructure, built upon the economic base... even though Mr. George Lansbury were Prime Minister and every seat in the House occupied by Socialist deputies, the capitalist system being what it is they would be powerless to effect anything more than the slow paced reform of which the sole aim is to make men and masters settle down in a comfortable but unholy alliance... the capitalists own the states. A handful of private capitalists could make England, or any other country, bankrupt within a week."

This article brought a rebuke from H. G. Wells: That you do not know what you want in economic and social organization, that the wild cry for freedom which makes me so sympathetic with your paper, and which echoes through every column of it, is unsupported by the ghost of a shadow of an idea how to secure freedom. What is the good of writing that economic arrangements will have to be adjusted to the Soul of Man if you are not prepared with anything remotely resembling a suggestion of how the adjustment is to be affected?"

Mary Gawthorpe also criticised Dora Marsden for her what she called her "philosophical anarchism". She told her that she "was not really an anarchist at all" but one who believed in rank, with herself at the top. Mary added: "Intellectually you have signed on as a member of the coming aristocracy. Free individuals you would have us be, but you would have us in our ranks... I watch you from week to week governing your paper. You have your subordinates. You say to one go and she goes, to another come, and she comes."

Mary Gawthorpe had suffered severe internal injuries after being beaten up by stewards at a meeting. She was also imprisoned several times and hunger strikes and force-feeding badly damaged her health and in March 1912, she was unable to continue working as co-editor of The Freewoman. Marsden wrote in the journal that "we earnestly hope that the coming months will see her restored to health". Although Mary was ill, she had not resigned on health grounds, but because of what she claimed was "Dora's bullying" and her "philosophical anarchism". Gawthorpe returned all Dora's letters and asked her not to write again: "The sight of your letters I am obliged to confess turns me white with emotion and I have acute heart attacks following on from that."

In the edition published on 18th June 1912, Ada Nield Chew created further controversy with an article on the role of women in marriage. She argued that the emancipation of women depended on their gaining economic independence and rejecting the idea that their natural lifelong vocation was domestic and maternal. Ada, a working-class woman with children, added that: "A married woman dependent on her husband earns her living by her sex... Why, in the name of reason and common sense, should we condemn a mother to be a life-long parasite because she has had one or more babies to care for?"

In September 1912, The Freewoman was banned by W. H. Smith because "the nature of certain articles which have been appearing lately are such as to render the paper unsuitable to be exposed on the bookstalls for general sale." Dora Marsden argued that this was not the only reason the journal was banned: "The animosity we rouse is not roused on the subject of sex discussion. It is aroused on the question of capitalism. The opposition in the capitalist press only broke out when we began to make it clear that the way out of the sex problem was through the door of the economic problem."

Charles Grenville wrote to Dora Marsden complaining that the journal was losing about £20 a week and told her he was thinking of withdrawing as the publisher of the magazine. Marsden replied: "You have put money into the paper. I have put in the whole of my brain, power and personality. Without your money I would not have started, without my brain the paper could not have lived and shown the signs of flourishing which it undoubtedly has."

When Edward Carpenter realised the journal was being brought to an end, he wrote to Dora Marsden: "The Freewoman did so well during its short career under your editorship, it was so broad-minded and courageous that its cessation has been real loss to the cause of free and rational discussion of human problems."

The last edition appeared on 10th October 1912. Dora Marsden told her readers: "The editorial work has not been easy. We have been hemmed in on every side by lack of funds. We have, moreover, been promoting a constructive creed, which had not only to be erected as we went along, we had also to deal with the controversy which this constructive creed left in its wake.... The entire campaign has been carried on indeed only at the cost of a total expenditure of energy, and we, therefore, do not hold it possible to continue the same amount of work, with diminished resources, if in addition, we have to bear the entire anxiety of securing such resources as are to be at our disposal."

On this day in 1911 Elsie Duval, of the Women Social & Political Union (WSPU) was arrested for obstructing the police. Elsie Duval, daughter of Ernest Duval, was born in 1892. Her mother, Emily Duval, was a member of the WSPU before joining the Women's Freedom League in 1907. In January 1908 she was sentenced to one month's imprisonment after taking part in a demonstration at the home of Herbert Asquith. In 1911 Emily Duval left the WFL because it was not militant enough and rejoined the WSPU. Elsie's father, was also a supporter of women's suffrage and was a member of the Men's League For Women's Suffrage. Her brother, Victor Duval, was also imprisoned several times for taking part in demonstrations.

Elsie Duval joined the WSPU at the age of fifteen. She was at first too young to be involved in militant activity and was not arrested until 23rd November 1911 on a charge of obstructing the police. In March 1912 the WSPU organised a new campaign that involved the large-scale smashing of shop-windows. Elsie took part in this campaign and in July was sentenced to a month's imprisonment for breaking a window in Clapham. While in prison she was forcibly fed nine times.

Elsie Duval also took part in the WSPU's arson campaign. It is believed she was responsible for burning Sanderstead Station. She was arrested for "loitering with intent" on 3rd April 1913. She was sentenced to one month's imprisonment. After being released under the Cat and Mouse Act, she escaped with her boyfriend, Hugh Franklin, to Belgium and stayed in Brussels. She received a letter from Jessie Kenney that said: "Miss Pankhurst thinks it would be better for you to stay where you are for the time being and until you get stronger."

On 4th August, 1914, England declared war on Germany. Two days later the NUWSS announced that it was suspending all political activity until the war was over. The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort. Duval and Franklin now returned to England.

During the First World War she applied to work with Louisa Garrett Anderson and Flora Murray in a hospital in Claridge Hotel in Paris. The offer was rejected and on 28th September 1915 she married Hugh Franklin in the West London Synagogue. His father disinherited him for marrying out of the Jewish faith and never saw him again.

Elsie Duval became ill during the influenza epidemic and died of heart failure on 1st January 1919. It is believed that her heart had been weakened by the treatment she received in prison.

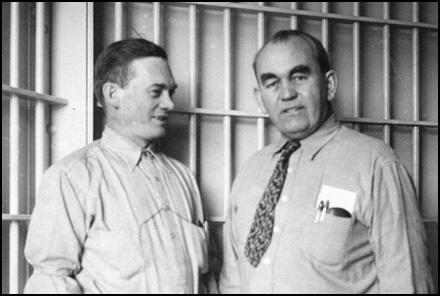

On this day in 1917 the San Francisco Call reported that Tom Mooney and Warren Billings had been framed by District Attorney Charles Fickert. On 22nd July, 1916, employers in San Francisco organized a march through the streets in favour of an improvement in national defence. Critics of the march such as William Jennings Bryan, claimed that the Preparedness March was being organized by financiers and factory owners who would benefit from increased spending on munitions.

During the march a bomb went off in Steuart Street killing six people (four more died later). Two witnesses described two dark-skinned men, probably Mexicans, carrying a heavy suitcase near to where the bomb exploded. The Chamber of Commerce immediately offered a reward of $5,000 for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the dynamiters. Other organizations and individuals added to this sum and the reward soon reached $17,000. Offering such a large reward was condemned by the editor of the New York Times claiming it was a "sweepstake for perjurers".

On the evening of the bombing Martin Swanson went to see the District Attorney, Charles Fickert. Swanson told Fickert that despite the claims that it was the work of Mexicans, he was convinced that Tom Mooney and Warren Billings were responsible for the explosion. The next day Swanson resigned from the Public Utilities Protective Bureau and began working for the District Attorney's office. On 26th July 1916, Fickert ordered the arrest of Mooney, his wife Rena Mooney, Warren Billings, Israel Weinberg and Edward Nolan. Mooney and his wife were on vacation at Montesano at the time. When Mooney read in the San Francisco Examiner that he was wanted by the police he immediately returned to San Francisco and gave himself up. The newspapers incorrectly reported that Mooney had "fled the city" and failed to mention that he had purchased return tickets when he left San Francisco.

None of the witnesses of the bombing identified the defendants in the lineup. The prosecution case was instead based on the testimony of two men, an unemployed waiter, John McDonald and Frank Oxman, a cattleman from Oregon. They claimed that they saw Warren Billings plant the bomb at 1.50 p.m. Oxman saw Tom Mooney and his wife talking with Billings a few minutes later. However, at the trial, a photograph showed that the couple were over a mile from the scene. A clock in the photograph clearly read 1.58 p.m. The heavy traffic at the time meant that it was impossible for Mooney and his wife to have been at the scene of the bombing. Despite this, Mooney was sentenced to death and Billings to life-imprisonment. Rena Mooney and Israel Weinberg were found not guilty and Edward Nolan was never brought to trial.

A large number of people believed that Billings and Mooney had been framed. Those involved in the campaign to get them released included Robert Minor, Fremont Older, George Bernard Shaw, Heywood Broun, Samuel Gompers, Eugene V. Debs, Roger Baldwin, John Dewey, John Haynes Holmes, Oswald Garrison Villard, Norman Hapgood, Crystal Eastman, Norman Thomas, Upton Sinclair, Theodore Dreiser, Sinclair Lewis, Lincoln Steffens, H. L. Mencken, Burton K. Wheeler, Sherwood Anderson, Abraham Muste, Harry Bridges, James Larkin, James Cannon, William Z. Foster, Alexander Berkman, Emma Goldman, William Haywood, William A. White, Carl Sandburg, Arturo Giovannitti and Robert Lovett.

Mooney's defence team complained about the method of selecting his jury. Bourke Cockran pointed out that in San Francisco "each Superior Court Judge places in the box from which the trial jurors are drawn the names of such persons as he may think proper. In theory he is supposed to choose persons peculiarly well qualified to decide issues of fact. In actual practice he places in the box the names of men who ask to be selected. The practical result is that a jury panel is a collection of the lame, the halt, the blind, and the incapable, with a few exceptions, and these are well known to the District Attorney who is thus enabled to pick a jury of his own choice." It was also discovered that William MacNevin, the foreman of Mooney's jury, was a close friend of Edward Cunha, who led the prosecution. MacNevin's wife later claimed her husband was in collusion with Cunha during the trial.

In 1917 the American government became concerned about the conviction and imprisonment of Tom Mooney and Warren Billings and the Secretary of Labor, William Bauchop Wilson, delegated John Densmore, the Director of General Employment, to investigate the case. By secretly installing a dictaphone in the private office of the District Attorney he was able to discover that Mooney and Billings had probably been framed by Charles Fickert and Martin Swanson. The report was leaked to Fremont Older who published it in the San Francisco Call on 23rd November 1917.

There were protests all over the world about this miscarriage of justice and President Woodrow Wilson called on William Stephens, the Governor of California, to look again at the case. Two weeks before Tom Mooney was scheduled to hang, Stephens commuted his sentence to life imprisonment in San Quentin. Soon afterwards Mooney wrote to Stephens: "I prefer a glorious death at the hands of my traducers, you included, to a living grave."

In November 1920, Draper Hand of the San Francisco Police Department, went to Mayor James Rolph and admitted that he had helped Charles Fickert and Martin Swanson to frame Mooney. Hand also confessed that he had arranged for John McDonald to get a job when he began threatening to tell the newspapers that he had lied in court about Mooney and Billings.

Mooney's defence team now began to search for MacDonald. He was found in January 1921 and agreed to make a full confession. He claimed he did see two men with the large suitcase but was unable to get a good look at them. When he reported the incident to District Attorney Charles Fickert he was asked to say the men were identify Warren Billings and Tom Mooney. Fickert said that if he did this "I will see that you get the biggest slice of the reward." Later two witnesses, Edgar Rigall and Earl K. Hatcher, came forward and provided evidence that Frank Oxman was 200 miles away during the bombing and could not have seen what he told the court at the trial of Mooney.

In February 1921 John McDonald confessed that the police had forced him to lie about the planting of the bomb. Despite this new evidence the Californian authorities refused a retrial. After the publication of this new evidence it was generally believed that Charles Fickert and Martin Swanson had framed Mooney and Billings. However, Republican governors over the next twenty years: William Stephens (1917-1923), Friend Richardson (1923-1927), Clement Young (1927-1931), James Rolph (1931-1934) and Frank Merriam (1934-39) all refused to order the release of the two men.

The international campaign to free Tom Mooney and Warren Billings continued. In a survey carried out in 1935 and it was discovered that Tom Mooney was one of the four best known Americans in Europe (other three were Franklin D. Roosevelt, Charles A. Lindbergh and Henry Ford).

In 1937 a group of politicians led by Caroline O'Day, Nan Honeyman, Jerry O'Connell, Emanuel Celler, James E. Murray, Vito Marcantonio, Gerald Nye and Usher Burdick asked President Franklin D. Roosevelt to intercede in the case. When Roosevelt declined Murray and O'Connell introduced a resolution in the Senate calling on Governor Frank Merriam to pardon Mooney and Billings.

In November 1938 Culbert Olson was elected as Governor of California. He was the first member of the Democratic Party to hold this office for forty-four years. Soon after gaining power Olson ordered that Tom Mooney and Warren Billings should be released from prison. Rena Mooney, who welcomed her husband as he left San Quentin, was quoted as saying: "These twenty-two long years have been moth-eaten. Life to me has been something like a cloak. There is little left but the tatters."

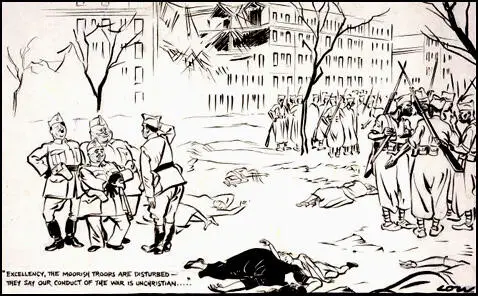

On this day in 1936 David Low produced the cartoon, Progress of Civilization in Spain. In 1935 Low joined with other radicals, such as Stafford Cripps, Nye Bevan, Ellen Wilkinson, J. B. Priestley, Victor Gollancz, Henry Nevinson and Norman Angell to complain about Britain's foreign policy towards Nazi Germany. Low was especially appalled by what he called the "Government's supine attitude to foreign intervention in Spain" during the Spanish Civil War. (42)

On 5th August 1936, Low published a cartoon entitled Correct Attitudes in Spain. A man marked "Democracy" is being attacked by two men "Army Fascism" and "Fascist Intervention". Standing alongside is Anthony Eden, the British prime minister, and Leon Blum, the French premier. Eden is saying: "Heah, I say, fair play! You shouldn't encourage the agressor, you know. After all, my friend and I aren't trying to help his victim."

Although he was a staunch socialist, Low, did not usually join political groups because he thought he could be more effective by remaining and independent critic. However, he did become a member of Friends of the Spanish Republic and the International Association of Writers for the Defence of Culture. He felt so strongly about the situation in Spain that he wrote letters to The Times and made public speeches on the subject.