On this day on 14th November

On this day in 1887 Hanna Solf, was born in Germany. A member of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) she was close to Elisabeth von Thadden, who ran a Protestant boarding school at Schloss Wieblingen, near Heidelberg. Von Thadden was opposed to the policies of Adolf Hitler and refused to allow her girls to join the League of German Girls at the boarding school. She did not keep her dislike of Hitler a secret and In 1941 the authorities withdrew the necessary permission to run the school.

Hanna Solf became the head of a anti-Nazi group who were members of the Confessional Church. Other members of the Solf Circle included Elisabeth von Thadden, Otto Kiep, Hilger van Scherpenberg, Erich Graf von Bernstorff, Fanny von Kurowsky, Arthur Zarden, Irmgard Zarden and Herbert Mumm von Schwarzenstein. According to Peter Hoffmann: "The Solf Circle consisted of a group of like-minded people who simply wished to oppose and counter the oppression, persecution, humiliation and degradation of human beings by the regime."

Helmuth von Moltke, the leader of the Kreisau Circle, a small group of intellectuals who were ideologically opposed fascism, was also a member of Abwehr, the Counter-Intelligence Service, Foreign Division, discovered that the telephones of the Solf Circle were about to be tapped and so he warned them to be careful how they communicated to each other. Unfortunately, one of the members of this group, Paul Reckzeh, was a Nazi spy. He now told the authorities that Moltke was a member of the German resistance. As a result Moltke was arrested.

Hanna Solf and other members of the Solf Circle were arrested on 13th January, 1944. Arthur Zarden, who was interrogated by Herbert Lange, was known for horribly torturing prisoners, committed suicide on 18th January. (6) Hanna Solf was not charged for diplomatic reasons and instead was sent to Ravensbrück Concentration Camp.(7)

Elisabeth von Thadden, Otto Kiep, Hilger van Scherpenberg, Herbert Mumm von Schwarzenstein, Fanny von Kurowsky and Irmgard Zarden were charged with "high treason, sedition, defeatism and favouring the enemy" and appeared in court on 1st July, 1944. Thadden was further charged that she had "aided and abetted wartime enemies of the Greater German Reich by undermining the war effort and by conspiring to commit high treason".

A fellow defendant commented: "She (Elisabeth von Thadden) was very composed. Brutes and proles were a completely alien world to her. Thadden was treated horribly after the verdict; she always had her hands shackled behind her back and she could no longer do anything herself. One can imagine how her wrists must have looked, because she had metal shackles. I'm sure she was composed and self-possessed until her head was chopped off. "

Elisabeth von Thadden, Otto Kiep and Herbert Mumm von Schwarzenstein were sentenced to death and executed. Scherpenberg received two years hard labour but Kurowsky and Zarden were acquitted. Hanna Solf remained in Ravensbrück until liberated by the Red Army at the end of the war.

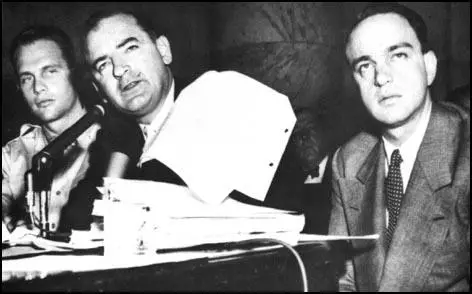

On this day in 1908 Joseph McCarthy was born on a farm in Appleton, Wisconsin, on 14th November, 1908. His parents were devout Roman Catholics and Joseph was the fifth of nine children. He left school at 14 and worked as a chicken farmer before managing a grocery store in the nearby town of Manawa.

McCarthy returned to high school in 1928 and after achieving the necessary qualifications, won a place at Marquette University. After graduating McCarthy worked as a lawyer but was fairly unsuccessful and had to supplement his income by playing poker.

McCarthy was originally a supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal. However, after failing to become the Democratic Party candidate for district attorney, he switched parties and became the Republican Party candidate in an election to become a circuit court judge. McCarthy shocked local officials by fighting a dirty campaign. This included publishing campaign literature that falsely claimed that his opponent, Edgar Werner, was 73 (he was actually 66). As well as suggesting that Werner was senile, McCarthy implied that he was guilty of financial corruption.

When the United States entered the Second Word War McCarthy resigned as a circuit judge and joined the U.S. Marines. After the war McCarthy ran against Robert La Follette to become Republican candidate for the senate. As one of his biographers has pointed out, his campaign posters pictured him in "full fighting gear, with an aviator's cap, and belt upon belt of machine gun ammunition wrapped around his bulky torso." He claimed he had completed thirty-two missions when in fact he had a desk job and only flew in training exercises.

In his campaign, McCarthy attacked La Follette for not enlisting during the war. He had been forty-six when Pearl Harbor had been bombed, and was in fact too old to join the armed services. McCarthy also claimed that La Follette had made huge profits from his investments while he had been away fighting for his country. The suggestion that La Follette had been guilty of war profiteering (his investments had in fact been in a radio station), was deeply damaging and McCarthy won by 207,935 to 202,557. La Follette, deeply hurt by the false claims made against him, retired from politics, and later committed suicide.

On his first day in the Senate, McCarthy called a press conference where he proposed a solution to a coal-strike that was taking place at the time. McCarthy called for John L. Lewis and the striking miners to be drafted into the Army. If the men still refused to mine the coal, McCarthy suggested they should be court-martialed for insubordination and shot.

McCarthy's first years in the Senate were unimpressive. People also started coming forward claiming that he had lied about his war record. Another problem for McCarthy was that he was being investigated for tax offences and for taking bribes from the Pepsi-Cola Company. In May, 1950, afraid that he would be defeated in the next election, McCarthy held a meeting with some of his closest advisers and asked for suggestions on how he could retain his seat. Edmund Walsh, a Roman Catholics priest, came up with the idea that he should begin a campaign against communist subversives working in the Democratic administration.

McCarthy also contacted his friend, the journalist, Jack Anderson. In his autobiography, Confessions of a Muckraker, Anderson pointed out: "At my prompting he (McCarthy) would phone fellow senators to ask what had transpired this morning behind closed doors or what strategy was planned for the morrow. While I listened in on an extension he would pump even a Robert Taft or a William Knowland with the handwritten questions I passed him."

In return, Anderson provided McCarthy with information about politicians and state officials he suspected of being "communists". Anderson later recalled that his decision to work with McCarthy "was almost automatic.. for one thing, I owed him; for another, he might be able to flesh out some of our inconclusive material, and if so, I would no doubt get the scoop." As a result Anderson passed on his file on the presidential aide, David Demarest Lloyd.

Joseph McCarthy also began receiving information from his friend, J. Edgar Hoover, the head of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). William C. Sullivan, one of Hoover's agents, later admitted that: "We were the ones who made the McCarthy hearings possible. We fed McCarthy all the material he was using." McCarthy made a speech in Salt Lake City where he attacked Dean Acheson, the Secretary of State, as "a pompous diplomat in striped pants".

On 9th February, 1950, at a meeting of the Republican Women's Club in Wheeling, West Virginia, McCarthy claimed that he had a list of 205 people in the State Department that were known to be members of the American Communist Party (later he reduced this figure to 57). McCarthy went on to argue that some of these people were passing secret information to the Soviet Union. He added: "The reason why we find ourselves in a position of impotency is not because the enemy has sent men to invade our shores, but rather because of the traitorous actions of those who have had all the benefits that the wealthiest nation on earth has had to offer - the finest homes, the finest college educations, and the finest jobs in Government we can give."

The list of names was not a secret and had been in fact published by the Secretary of State in 1946. These people had been identified during a preliminary screening of 3,000 federal employees. Some had been communists but others had been fascists, alcoholics and sexual deviants. As it happens, if McCarthy had been screened, his own drink problems and sexual preferences would have resulted in him being put on the list.

Raymond Gram Swing, who worked for the the Blue Radio Network, later explained the impact of his speech: "In those four years he (McCarthy) throve as a demagogue, and frightened many, if not all, diplomats into failing to give their frank opinions to the government for fear of being falsely accused of Communist tendencies. The government thus suffered from a debility among diplomats. Employees in the Information Agency had to smother their political judgments lest they be pilloried by Senator McCarthy's congressional committee. It was a season of terror for which Senator McCarthy somewhat incorrectly bears all the blame. He became the name-symbol of the epoch, not by accident, for that was precisely what he wanted. He found the Communist issue when he needed something to make himself known and powerful. Through his exploitation of it and by his attacks on innocent persons, he did the United States more harm at home, and in democratic countries abroad, than any individual in modern times."

On 20th February, 1950, McCarthy made a six hour speech on the Senate floor supporting the allegations he had made in Salt Lake City. This time he did not describe them as "card-carrying communists" because this had been shown to be untrue. Instead he argued that his list were all "loyalty risks". He also claimed that one of the president's speech-writers, was a communist. David Demarest Lloyd immediately issued a statement where he defended himself against McCarthy's charges. President Harry S. Truman not only kept him on but promoted him to the post of Administrative Assistant. Lloyd was indeed innocent of these claims and McCarthy was forced to withdraw these allegations. As Anderson admitted: "At my instigation, then, Lloyd had been done an injustice that was saved from being grevious only by Truman's steadfastness."

McCarthy also claimed that the Democratic administration had been infiltrated by communist subversives. McCarthy named four of these people, who had held left-wing views in their youth, but when Democrats accused McCarthy of smear tactics, he suggested they were part of this communist conspiracy. This claim was used against his critics who were up for re-election in 1950. Many of them lost and this made other Democrats reluctant to criticize McCarthy in case they became targets of his smear campaigns.

Drew Pearson immediately launched an attack on Joseph McCarthy. He pointed out that only three people on the list were State Department officials. When this list was first published four years ago, Gustavo Duran and Mary Jane Keeney had both resigned from the State Department in 1946. The third person, John S. Service, had been cleared after a prolonged and careful investigation. Pearson also pointed out that none of these people had been members of the American Communist Party. Jack Anderson asked Pearson to stop attacking McCarthy: "He is our best source on the Hill." Pearson replied, "He may be a good source, Jack, but he's a bad man."

With the war going badly in Korea and communist advances in Eastern Europe and in China, the American public were genuinely frightened about the possibilities of internal subversion. McCarthy, as chairman of the Government Committee on Operations of the Senate, was in an ideal position to exploit this situation.

For the next two years McCarthy investigated various government departments and questioned a large number of people about their political past. Some people lost their jobs after they admitted they had been members of the Communist Party. McCarthy made it clear to the witnesses that the only way of showing that they had abandoned their left-wing views was by naming other members of the party.

This witch-hunt and anti-communist hysteria became known as McCarthyism. Some left-wing artists and intellectuals were unwilling to live in this type of society and people such as Joseph Losey, Richard Wright, Ollie Harrington, James Baldwin, Herbert Biberman, Lester Cole and Chester Himes went to live and work in Europe.

McCarthyism was mainly used against Democrats associated with the New Deal policies introduced by Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1930s. Harry S. Truman and members of his Democratic administration such as George Marshall and Dean Acheson, were accused of being soft on communism. Truman was portrayed as a dangerous liberal and McCarthy's campaign helped the Republican candidate, Dwight Eisenhower, win the presidential election in 1952.

After what had happened to McCarthy's opponents in the 1950 election, most politicians were unwilling to criticize him in the Senate. As The Boston Post pointed out: "Attacking him is this state is regarded as a certain method of committing suicide. One notable exception was William Benton, a senator from Connecticut and the owner of Encyclopaedia Britannica. McCarthy and his supporters immediately began smearing Benton. It was claimed that while Benton had been Assistant Secretary of State he had protected known communists and that he had been responsible for the purchase and display of "lewd art works". Benton, who was also accused of being disloyal by McCarthy for having much of his company's work printed in England, was defeated in the 1952 elections.

Joseph McCarthy informed Jack Anderson that he had evidence that Professor Owen Lattimore, director of the Walter Hines Page School of International Relations at Johns Hopkins University, was a Soviet spy. Drew Pearson, who knew Lattimore, and while accepting he held left-wing views, he was convinced he was not a spy. In his speeches, McCarthy referred to Lattimore as "Mr X... the top Russian spy... the key man in a Russian espionage ring."

On 26th March, 1950, Pearson named Lattimore as McCarthy's Mr. X. Pearson then went onto defend Lattimore against these charges. McCarthy responded by making a speech in Congress where he admitted: "I fear that in the case of Lattimore I may have perhaps placed too much stress on the question of whether he is a paid espionage agent."

McCarthy then produced Louis Budenz, the former editor of The Daily Worker. Budenz claimed that Lattimore was a "concealed communist". However, as Anderson admitted: "Budenz had never met Lattimore; he spoke not from personal observation of him but from what he remembered of what others had told him five, six, seven and thirteen years before."

Drew Pearson now wrote an article where he showed that Budenz was a serial liar: "Apologists for Budenz minimize this on the ground that Budenz has now reformed. Nevertheless, untruthful statements made regarding his past and refusal to answer questions have a bearing on Budenz's credibility." He went on to point out that "all in all, Budenz refused to answer 23 questions on the ground of self-incrimination".

Owen Lattimore was eventually cleared of the charge that he was a Soviet spy or a secret member of the American Communist Party and like other victims of McCarthyism, he went to live in Europe and for several years was professor of Chinese studies at Leeds University.

Despite the efforts of Jack Anderson, by the end of June, 1950, Drew Pearson had written more than forty daily columns and a significant percentage of his weekly radio broadcasts, that had been devoted to discrediting the charges made by Joseph McCarthy.

Joe McCarthy now told Anderson: "Jack, I'm going to have to go after your boss. I mean, no holds barred. I figure I've already lost his supporters; by going after him, I can pick up his enemies." McCarthy, when drunk, told Assistant Attorney General Joe Keenan, that he was considering "bumping Pearson off".

On 15th December, 1950, McCarthy made a speech in Congress where he claimed that Pearson was "the voice of international Communism" and "a Moscow-directed character assassin." McCarthy added that Pearson was "a prostitute of journalism" and that Pearson "and the Communist Party murdered James Forrestal in just as cold blood as though they had machine-gunned him."

Over the next two months McCarthy made seven Senate speeches on Drew Pearson. He called for a "patriotic boycott" of his radio show and as a result, Adam Hats, withdrew as Pearson's radio sponsor. Although he was able to make a series of short-term arrangements, Pearson was never again able to find a permanent sponsor. Twelve newspapers cancelled their contract with Pearson.

McCarthy and his friends also raised money to help Fred Napoleon Howser, the Attorney General of California, to sue Pearson for $350,000. This involved an incident in 1948 when Pearson accused Howser of consorting with mobsters and of taking a bribe from gambling interests. Help was also given to Father Charles Coughlin, who sued Pearson for $225,000. However, in 1951 the courts ruled that Pearson had not libeled either Howser or Coughlin.

Only the St. Louis Star-Times defended Pearson. As its editorial pointed out: "If Joseph McCarthy can silence a critic named Drew Pearson, simply by smearing him with the brush of Communist association, he can silence any other critic." However, Pearson did get the support of J. William Fulbright, Wayne Morse, Clinton Anderson, William Benton and Thomas Hennings in the Senate.

In 1952 McCarthy appointed Roy Cohn as the chief counsel to the Government Committee on Operations of the Senate. Cohn had been recommended by J. Edgar Hoover, who had been impressed by his involvement in the prosecution of Julius Rosenberg and Ethel Rosenberg. Soon after Cohn was appointed, he recruited his best friend, David Schine, to become his chief consultant.

McCarthy's next target was what he believed were anti-American books in libraries. His researchers looked into the Overseas Library Program and discovered 30,000 books by "communists, pro-communists, former communists and anti anti-communists." After the publication of this list, these books were removed from the library shelves.

For some time opponents of McCarthy had been accumulating evidence concerning his homosexual activities. Several members of his staff, including Roy Cohn and David Schine, were also suspected of having a sexual relationship. Although well-known by political journalists, the first article about it did not appear until Hank Greenspun published an article in the Las Vegas Sun in 25th October, 1952. Greenspun wrote that: "It is common talk among homosexuals in Milwaukee who rendezvous in the White Horse Inn that Senator Joe McCarthy has often engaged in homosexual activities."

Joseph McCarthy considered a libel suit against Greenspun but decided against it when he was told by his lawyers that if the case went ahead he would have to take the witness stand and answer questions about his sexuality. In an attempt to stop the rumours circulating, McCarthy married his secretary, Jeannie Kerr. Later the couple adopted a five-week old girl from the New York Foundling Home.

In October, 1953, McCarthy began investigating communist infiltration into the military. Attempts were made by McCarthy to discredit Robert Stevens, the Secretary of the Army. The president, Dwight Eisenhower, was furious and now realised that it was time to bring an end to McCarthy's activities. The United States Army now passed information about McCarthy to journalists who were known to be opposed to him. This included the news that McCarthy and Roy Cohn had abused congressional privilege by trying to prevent David Schine from being drafted. When that failed, it was claimed that Cohn tried to pressurize the Army into granting Schine special privileges. Drew Pearson, published the story on 15th December, 1953.

Some figures in the media, such as writers George Seldes and I. F. Stone, and cartoonists, Herb Block and Daniel Fitzpatrick, had fought a long campaign against McCarthy. Other figures in the media, who had for a long time been opposed to McCarthyism, but were frightened to speak out, now began to get the confidence to join the counter-attack. Edward Murrow, the experienced broadcaster, used his television programme, See It Now, on 9th March, 1954, to criticize McCarthy's methods. Newspaper columnists such as Walter Lippmann also became more open in their attacks on McCarthy.

The senate investigations into the United States Army were televised and this helped to expose the tactics of Joseph McCarthy. One newspaper, the Louisville Courier-Journal, reported that: "In this long, degrading travesty of the democratic process, McCarthy has shown himself to be evil and unmatched in malice." Leading politicians in both parties, had been embarrassed by McCarthy's performance and on 2nd December, 1954, a censure motion condemned his conduct by 67 votes to 22.

Raymond Gram Swing, who had been forced to resign from the Voice of America because of McCarthy, argued in his autobiography, Good Evening (1964) that this did not mark the end of McCarthyism: "I am more than a little disquieted that McCarthy's condemnation by the Senate and his subsequent death have satisfied so many people that McCarthyism is over. For one thing, I consider that the condemnation by the Senate has given unwarranted satisfaction. It was based on an altogether peculiar sense of the importance of secondary matters. I am profoundly grateful that the committee went as far as it did. But I feel that it left out of account in its condemnation most of what Senator McCarthy had injuriously done. It ignored his roughshod disregard of civil rights and his irrepressible mendacity, and the fact that they existed while he was acting with the authority of the Senate. These transgressions were not specifically and helpfully rebuked at the time or ever. American principles and ethics were not strengthened by the Senate resolution of condemnation. The nation did not become healthier through it. It simply was rid of a menace because some Senate conservatives realized that their dignity was being sullied."

McCarthy now lost the chairmanship of the Government Committee on Operations of the Senate. He was now without a power base and the media lost interest in his claims of a communist conspiracy. As one journalist, Willard A. Edwards, pointed out: "Most reporters just refused to file McCarthy stories. And most papers would not have printed them anyway."

Joseph McCarthy, who had been drinking heavily for many years, was discovered to have cirrhosis of the liver. An alcoholic, he was unable to take the advice of doctors and friends to stop drinking. Joseph McCarthy died in the Bethesda Naval Hospital on 2nd May, 1957. As the newspapers reported, McCarthy had drunk himself to death.

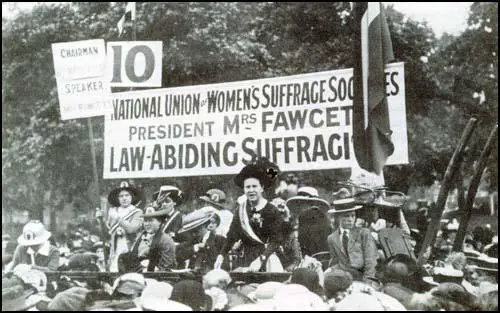

On this day in 1913 the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies makes statement in The Common Cause rejecting the use of violence in obtaining the vote for women. The NUWSS held public meetings, organised petitions, wrote letters to politicians, published newspapers and distributed free literature. The main demand was for the vote on the same terms "as it is, or may be" granted to men. It was thought that this proposal would be "more likely to find support than a broader measure that would put women into the electoral majority, and it might nevertheless play the part of the thin end of the wedge."

The Women's Social and Political Union disagreed with the NUWSS over the use of violence. Millicent Fawcett wrote to her sister, Elizabeth Garrett: "We have the best chance of Women's Suffrage next session that we have ever had, by far, if it is not destroyed by disgusting masses of people by revolutionary violence." Elizabeth agreed and replied: "I am quite with you about the WSPU. I think they are quite wrong. I wrote to Miss Pankhurst... I have now told her I can go no more with them."

culmination of the Pilgrimage on 26th July 1913.

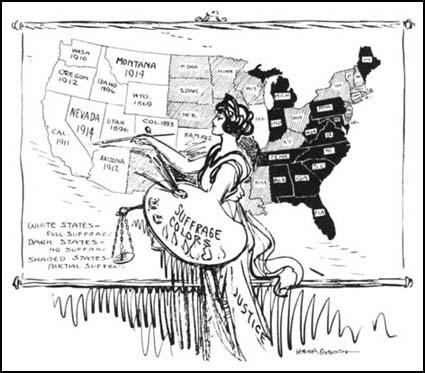

On this day in 1914 the Maryland Suffrage News publishes a cartoon on the progress of women's suffrage in the United States. Working with journals such as the Women Voter, The Women's Journal, Woman Citizen and The Masses, the suffragists mounted vigorous campaigns to gain the vote. They tended to concentrate their energies in trying to persuade state legislatures to submit to their voters amendments to state constitutions conferring full suffrage to women. Individual states gradually yielded to these demands. In 1893 women got the vote in Colorado, followed by Utah (1896), Idaho (1896), Washington (1910), California (1911), Arizona (1912), Kansas (1912), Oregon (1912), Illinois (1913), Nevada (1914) and Montana (1914).

Maryland Suffrage News (14th November, 1914)

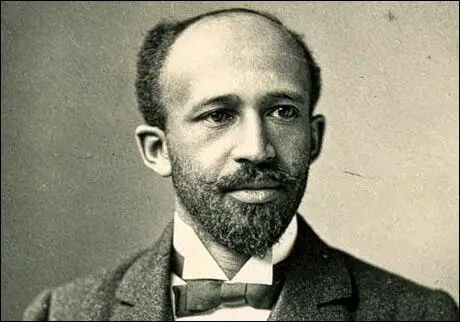

On this day in 1915 William Du Bois wrote an article about Booker T. Washington in The Crisis. In 1903 Du Bois published his ground-breaking The Souls of Black Folks. The book included an attack on Washington for not doing more in the campaign for African American civil rights. Du Bois own solution to this problem was to join forces with William Monroe Trotter to form the Niagara Movement in 1905. The group drew up a plan for aggressive action and demanded: manhood suffrage, equal economic and educational opportunities, an end to segregation and full civil rights.

William Du Bois began to read the works of Henry George, Jack London and John Spargo. He eventually became converted to socialism and in 1907 he wrote that "socialism was the one great hope of the Negro in America." He also became friendly with socialists such as Mary White Ovington and William English Walling.

The Niagara Movement had little impact on influencing those in power and in February, 1909, Du Bois joined with other campaigners for African American civil rights to form the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP). Other members included Mary White Ovington, William English Walling, Josephine Ruffin, Mary Talbert, Mary Church Terrell, Inez Milholland, Jane Addams, Mary McLeod Bethune, George Henry White, Charles Edward Russell, John Dewey, William Dean Howells, Charles Darrow, Lincoln Steffens, Ray Stannard Baker, Fanny Garrison Villard, Oswald Garrison Villard and Ida Wells-Barnett.

The NAACP started its own magazine, Crisis, in November, 1910. The magazine was edited by Du Bois and contributors to the first issue included Oswald Garrison Villard and Charles Edward Russell. The magazine soon built up a large readership amongst black people and white sympathizers. By 1919 Crisis was selling 100,000 copies a month.

In the newspaper Du Bois campaigned against lynching, Jim Crow laws, sexual inequality. He told his readers in October, 1911, that: "Every argument for Negro suffrage is an argument for women's suffrage; every argument for women's suffrage is an argument for Negro suffrage; both are great moments in democracy. There should be on the part of Negroes absolutely no hesitation whenever and wherever responsible human beings are without voice in their government." In 1912 he supported Eugene Debs, the Socialist Party candidate for president. He particularly admired the way that Debs refused to address segregated audiences in the South.

When Booker T. Washington died, William Du Bois wrote an article about him in The Crisis: "Booker T. Washington was the greatest Negro leader since Frederick Douglass, and the most distinguished man, white or black who has come out of the South since the Civil War. On the other hand, in stern justice, we must lay on the soul of this man, a heavy responsibility for the consummation of Negro disfranchisement, the decline of the Negro college and the firmer establishment of color caste in this land."

On this day in 1933 the second Asian to be elected as a MP, Mancherjee Bhownaggree, died. He was born in Bombay, India, on 15th August, 1851. The son of a merchant, he was educated at Elphinstone College and the University of Bombay, before becoming a journalist.

In 1872 Bhownaggree replaced his father as head of the Bombay State Agency. He later became Judicial Councillor of Behavnager, before moving to England in 1882, where he worked as a lawyer.

A member of the Conservative Party, Bhownaggree was chosen as Bethnel Green candidate for the 1895 General Election. He won the seat and therefore became the second Asian to be elected to the House of Commons. The Liberal Party MP, Dadabhai Naoroji, had represented Finsbury Central between 1892-95. Bhownaggree, unlike Naoroji, was a strong supporter of British rule in India.

Bhownaggree retired from politics after being defeated in the 1906 General Election. He gave generously to local charities and in memory of his dead sister, donated the Bhownagree Gallery in the Commonwealth Institute.

On this day in 1938 Dorothy Thompson makes a radio broadcast in the US on anti-Semitism in Germany. According to her biographer, Marion K. Sanders, when Dorothy was eight her mother died from blood poisoning after a bungled abortion performed by Dorothy's maternal grandmother." Dorothy rebelled after her mother's death and her father's remarriage and she was sent to Chicago to live with her aunt. While studying politics and economics at Syracuse University she became a suffragist and was involved in the campaign to obtain the vote for women. After the First World War Thompson went to Europe to become a freelance writer.

In 1920 she persuaded the International News Service to let her cover a Zionist conference in Vienna. This work resulted in her being employed as a European correspondent for the Philadelphia Public Ledger. Later she acquired a similar post with the New York Post and in 1925 she was appointed as head of its Berlin bureau in Germany.

During this period she became friends with Raymond Gram Swing and John Gunther while working in Germany. Ken Cuthbertson, the author of Inside: The Biography of John Gunther (1992), has pointed out: "Thompson, who was taken with John Gunther, befriended him both as a young man and a pupil. Theirs was an intimate, albeit platonic (as far as is known), relationship which endured through good times and bad."

On 14th May 1928 Thompson married Sinclair Lewis. After interviewing Adolf Hitler in 1931 she wrote about the dangers of him winning power in Germany. A strong opponent of Hitler and his government, in 1934 Thompson became the first American correspondent to be expelled from Nazi Germany. A fellow journalist, Raymond Gram Swing, compared her writing with Freda Kirchwey: "I wish to say that she (Kirchwey) was one of the best and most likable journalists with whom I ever worked. I am tempted to call her the best woman journalist I ever encountered, but hesitate to rank her ahead of Dorothy Thompson, who was a better writer."

On her return to the United States Thompson joined the New York Tribune and in 1936 began writing a newspaper column, On the Record. The following year she began broadcasting for the NBC. Thompson also wrote for the Ladies' Home Journal and developed such a large following that Time Magazine called her the second most popular woman in America, after Eleanor Roosevelt. Books by Thompson included New Russia, (1928) and I Saw Hitler! (1932).

On 14th November, 1938 she gave a radio broadcast on the actions of Herschel Grynzspan. "He (Grynzspan) read that Jewish children had been stood on platforms in front of classes of German children and had had their features pointed to and described by the teacher as marks of a criminal race. He read that men and women of his race, amongst them scholars and a general decorated for his bravery had been forced to wash the streets, while the mob laughed. There were men of his race, whom he had been taught to venerate - scientists and educators and scholars who once had been honored by their country. He read that they had been driven from their posts. He heard that the Nazi government had started all this because they said the Jews had made them lose the World War. But Herschel had not even been born when the World War ended. He was seventeen years old. Herschel had a pistol. I don't know why he had it. Maybe he had bought it somewhere thinking to use it on himself, if the worst came to the worst. Thousands of men and women of his race had killed themselves in the last years, rather than live like hunted animals. Still, he lived on.

Then, a few days ago, he got a letter from his father. His father told him that he had been summoned from his bed, and herded with thousands of others into a train of box cars, and shipped over the border, into Poland. He had not been allowed to take any of his meager savings with him. Just fifty cents. 'I am penniless,' he wrote to his son.... This was the end. Herschel fingered his pistol and thought: "Why doesn't someone do something! Why must we be chased around the earth like animals!' Herschel was wrong. Animals are not chased around the world like this. In every country there are societies for the prevention of cruelty to animals. But there are none for the prevention of cruelty to people. Herschel thought of the people responsible for this terror. Right in Paris were some, who were the official representatives of these responsible people. Maybe he thought that assassination is an honorable profession in these days. He knew, no doubt, that the youths who murdered the Austrian Chancellor Dollfuss are heroes in Nazi Germany, as are the murderers of Rathenau. Maybe he remembered that only four years ago the Nazi Leader himself had caused scores of men to be assassinated without a trial, and had justified it simply by saying that he was the law. And so Herschel walked into the German embassy and shot Herr von Rath. Herschel made no attempt to escape. Escape was out of the question anyhow."

On this day in 1946 Emily Balch was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. On the outbreak of the First World War, Balch and a group of women pacifists in the United States, began talking about the need to form an organization to help bring it to an end. On the 10th January, 1915, over 3,000 women attended a meeting in the ballroom of the New Willard Hotel in Washington and formed the Woman's Peace Party. Addams was elected chairman and other women involved in the organization included Mary McDowell, Florence Kelley, Alice Hamilton, Anna Howard Shaw, Belle La Follette, Fanny Garrison Villard, Jeanette Rankin, Lillian Wald, Edith Abbott, Grace Abbott, Mary Heaton Vorse, Freda Kirchwey, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Crystal Eastman, Carrie Chapman Catt, Emily Bach, and Sophonisba Breckinridge.

In April 1915, Arletta Jacobs, a suffragist in Holland, invited members of the Woman's Peace Party to an International Congress of Women in the Hague. Jane Addams was asked to chair the meeting and Balch, Alice Hamilton, Mary Heaton Vorse, Julia Lathrop, Leonora O'Reilly, Sophonisba Breckinridge and Grace Abbott went as delegates from the United States. Others who went to the Hague included Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Emily Hobhouse, (England); Chrystal Macmillan (Scotland) and Rosika Schwimmer (Hungary). Afterwards, Balch, Addams, Jacobs, Macmillan and Schwimmer went to to London, Berlin, Vienna, Budapest, Rome and Paris to speak with members of the various governments in Europe. During this time they met Edward Grey (13th May), Herbert Asquith (14th May), Gottlieb von Jagow (21st May), Theobold von Bethmann-Hollweg (22nd May), Karl von Sturgkh (26th May), Théophile Delcassé (12th June) and Rene Viviani (14th June).

Balch was also a member of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF). As a result of her anti-war activities, Balch was dismissed as professor of political economy at Wellesley College. She now concentrated on her peace work and became secretary of the WILPF (1918-22 and 1934-35). However, the emergence of Adolf Hitler changed her views on pacifism. She wrote: "It is not enough to sweep before your own door, nor to cultivate your own garden, nor to put out the fire when your own house is burning and disinterest yourself, as the diplmats say, when the frame house next door is in flames and the children calling from its nursery windows to be taken out."

Emily Balch won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1946. In her later life Balch wrote several important books including Refugees as Assets (1939), One Europe (1947) and Toward Human Unity, or Beyond Nationalism (1952). A few weeks before she died she wrote in her diary: "I am bringing my days to a close in a world still hag-ridden by the thought of war, and it is not given to us in this new atomic world to know how things will turn out. But when I reflect on the enormous changes that I have seen myself and the amazing resiliency and resourcefulness of mankind, how can I fail to be of good courage."

On this day in 1946, May Sinclair, who suffered from Parkinsin's Disease, died.

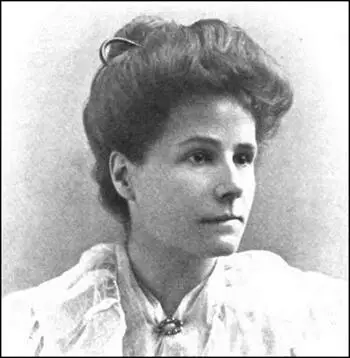

May Sinclair, the daughter of William Sinclair, a wealthy shipowner, was born in Rock Ferry, Cheshire in 1863. Sinclair was educated at Cheltenham Ladies College where Dorothea Beale recognised her writing talent.

Sinclair's first novel, Audrey Craven, was published in 1896. This was followed by Mr and Mrs Nevill Tyson (1897), The Divine Fire (1904), The Helpmate (1907) and The Creators (1910), a novel that dealt with the way men denigrate women's creativity. A collection of short-stories, The Flaw in the Crystal appeared in 1912.

A supporter of the women's suffrage movement, Sinclair was a member of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). On 1st March 1908 she had a letter published in Votes for Women where she said it was impossible to be a woman who did not admire the work of the WSPU.

In 1908 two members of the WSPU, Cicely Hamilton and Bessie Hatton, formed the Women Writers Suffrage League (WWSL). The WWSL stated that its object was "to obtain the vote for women on the same terms as it is or may be granted to men. Its methods are those proper to writers - the use of the pen." Women writers who joined the organisation included May Sinclair, Beatrice Harraden, Elizabeth Robins, Charlotte Despard, Alice Meynell, Olive Schreiner, Edith Ellis, Margaret Nevinson, Evelyn Sharp and Marie Belloc Lowndes. Sympathetic male writers such as Israel Zangwill and Laurence Housman, were allowed to become "Honorary Men Associates".

May Sinclair disapproved of the WSPU arson campaign and left the organisation and joined the Women's Freedom League (WFL). Like the WSPU, the WFL was a militant organisation that was willing the break the law. As a result, over 100 of their members were sent to prison after being arrested on demonstrations or refusing to pay taxes. However, members of the WFL was a completely non-violent organisation and opposed the WSPU campaign of vandalism against private and commercial property.

Dr. Almroth Wright, Britian's leading bacteriologist and immunologist was strongly opposed to women's suffrage. He argued that women's brains were innately different from men's and were not constituted to deal with social and public issues. Wright also vigorously opposed the professional development of women. Wright claimed that the suffragists were powered by their sexual frustration because of the shortage of men.

May Sinclair wrote a pamphlet Feminism (1912) where she pointed out the flaws in Wright's arguments: "Now, to have established his hypothesis on truly scientific lines Sir Almroth Wright should have had under his personal examination a majority, not only of the members of the Women's Social and Political Union, but of every Suffrage Society throughout the country; to say nothing of other countries, for in these, by his own showing, hysteria and a desire for the vote have not been invariably connected as agent and disease. That is to say, the 'hysteria bacillus' is not present in every case of suffragitis. And, if it is not present, what becomes of his hypothesis ? But let that pass. Sir Almroth Wright can reply that he is only investivating the British variety. And no doubt he can plead further that he has scientific precedent for his procedure. You are not bound to examine, say, every case of amoebic dysentery in order to establish the existence of entamoeba histolytica as the pathogenic germ. Enough, if you can eliminate other causes in a sufficient number of cases. True, but Sir Almroth Wright has not eliminated other causes. He has not searched for them. He is apparently unaware that they may exist. As for his cases, if he were really investigating a disease, would he not be careful to choose such only as were typical?"

Sinclair mentions friends in the movement such as Charlotte Despard, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst "among the militants, and among non-militants women like" Millicent Garrett Fawcett, Emily Davies and Frances Balfour. "They will present him with the thing he is investigating in its utmost purity and perfection. Even from the rank and file, from all grades and classes of suffrage societies the list could be prolonged indefinitely. Such women are alone representative of their movement; and if Sir Almroth Wright were to enquire closely, I think he would realise that in all of them the element of hysteria is either absent or negligible. Whoever charges such women with hysteria, neurosis, and degeneracy stands self-convicted of a lack of balance and acumen. Heaven forbid that I should pledge myself to the assertion that there are no hysterical, neurotic, or degenerate subjects in the Suffrage movement. I have one or two in my mind (as Sir Almroth Wright probably has) at this moment. The Suffrage Movement draws with a wide net, and in all large assemblies of human beings (men as well as women) you will find some neurosis and hysteria and degeneracy, neurosis being the scourge of modernity."

Working at the Medico-Psychological Clinic in London in 1913 May Sinclair discovered the work of Sigmund Freud. This influenced her book, The Three Sisters (1914) a study of middle-class women in a repressive society. This book marked the beginning of Sinclair's interest in psychology and her attempts to explore unconscious motivation.

On the outbreak of the First World War Sinclair went to France where she worked for the Motor Ambulance Unit. Sinclair was overcome by what she saw and after seventeen days she was sent home to England. Articles based on her experiences appeared in the The English Review during the summer of 1915. A fuller account, Journal of Impressions in Belgium, was published at the winter of 1915.

Other novels by May Sinclair include Tree of Heaven (1917) Mary Olivier (1919) and The Life and Death of Harriett Fream (1922). Influenced by the work of Sigmund Freud and Havelock Ellis, Sinclair became one of the leading exponents of the stream of consciousness novel.

Later novels included Arnold Waterlow (1924), The Rector of Wyck (1925) and The Allinghams (1927). She also published two volumes of short-stories, Uncanny Stories (1923) and The Intercessor and Other Stories (1931).

On this day in 1947 Marie Belloc Lowndes died.

Marie Belloc, the daughter of Louis Belloc, a French barrister, was born in France on 5th August 1868. Her mother was Elizabeth Rayner Parkes, the daughter of the Birmingham radical, Joseph Parkes, and granddaughter of Joseph Priestley.

The Belloc family moved to England in 1872. Like her brother, Hillaire Belloc, Marie was a talented writer and she had her first story published when she was only sixteen. This was followed by several novels that were well received by the critics. In 1896 Marie married Frederic Lowndes, the editor of The Times.

In 1908 the famous playwright, Cicely Hamilton, formed the Women Writers Suffrage League (WWSL). The WWSL stated that its object was "to obtain the vote for women on the same terms as it is or may be granted to men. Its methods are those proper to writers - the use of the pen." Belloc Lowndes was one of the first women to join the WWSL.

In 1913 Belloc Lowndes published highly successful novel, The Lodger. The fictionalized story about Jack the Ripper sold more than a million copies and was made into a popular feature film. Other important novels written by Belloc Lowndes include What Timmy Did (1921), The Story of Ivy (1928) and the Christine Diamond (1940).

Marie Lowndes Belloc died on 13th November 1947.

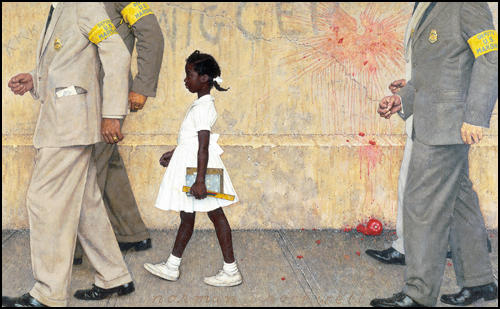

On this day in 1960 Ruby Bridges attended an all-White elementary school in Louisiana. Ruby was 6 years old, became involved in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) campaign to integrate the New Orleans School system. When she entered William Frantz Elementary School in 1960 she became the first African-American child to attend an all-white elementary school in the South. Norman Rockwell was so moved by this act of bravery he painted The Problem We All Live With (14th January, 1964).