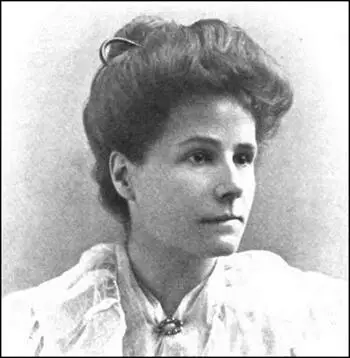

May Sinclair

Mary Amelia St Clair Sinclair, the youngest of six surviving children of William Sinclair (1829–1881) and Amelia Hind Sinclair (1821-1901) was born on 24th August 1863 in Thorncote, Rock Park, Rock Ferry, near Birkenhead. Both parents had been born in Belfast. Amelia Sinclair gave birth to seven children: William (1852-1896), Gertrude (1853-1854), Joseph (1856-1905), Francis (1857-1889), Harold (1858-1887) and Reginald (1861-1891) (1)

Amelia Sinclair was "an unimaginative and inflexible woman", and her strict views on religion and propriety made for a rather repressive atmosphere. (2) Sinclair later described her mother's dominance, in a letter to the Irish writer, Katherine Tynan Hinkson, as a "cold, bitter, narrow tyranny". (3)

William Sinclair was a wealthy shipowner and his business began to fail in the late 1860s. In 1870 he became bankrupt, and the family was dispersed. May lived with her mother in London. She had tuition at home, piano lessons, and access to her father's library, where she read widely in classical and English literature, history, and philosophy. She also learned German, Greek, and French. (4)

Cheltenham Ladies College

In 1881 she was sent to Cheltenham Ladies College where the headteacher, Dorothea Beale, recognised her writing talent. "Miss Beale gave her the sweet assurance that she could think and write lucidly; but she could not grant a desire that was nearly as strong as her hope: to be fully liberated from her mothers's relgious orthodoxy." (5)

Beale had noticed May Sinclair's gift for intellectual enquiry, and encouraged her to become a philosopher. Sinclair wrote her first philosophical essays and poems for the Cheltenham Ladies' College Magazine in 1882. The relationship between Sinclair and Beale was an important one. She noticed May Sinclair's gift for intellectual enquiry and encouraged her to become a philosopher. "consolidated her emerging sense of herself as a thinker, a woman of ideas". (6)

In 1881 her father, who had become an alcoholic, died. The next few years were also difficult. One brother, Harold, died in 1887, and then May Sinclair's favourite brother, Frank, died in 1889. In 1890, Sinclair, her mother, and the only brother left at home, Reginald, moved to Sidmouth. The change of air was meant to benefit Reginald's health, but he died in 1891. (7)

First Publications

May Sinclair's original ambition was to be a poet and philosopher. Her first book, Nakiketas and other Poems (1886), was published under the pseudonym Julian Sinclair. Essays in Verse (1892) was her first publication as May Sinclair. (8) In 1893 Sinclair met and fell in love with the curate Anthony Charles Deane. He wrote her " long letters, recommending books, and climbing the steep path to Sinclair's house to engage her in intense and deeply felt debate". However, in 1896, "Deane became engaged to somebody else, by which time Sinclair was in London, in financial trouble, looking for work as a teacher, and translating books for small amounts of money". (9)

Sinclair's first novel, Audrey Craven, was published in 1896, she was looking after her mother at Christchurch Road, Hampstead. The novel's psychological complexity and frankness shocked the critics. This was followed by Mr and Mrs Nevill Tyson (1897). Theophilus Boll has claimed that: "It is a cause of wonder that this novel was published at all, because it treats the sexual relations of man and wife with an almost medical frankness." (10)

In 1900, Amelia Sinclair suffered a heart attack and needed full-time care from her daughter. This made writing difficult and during this time she supported herself and her mother through translations. Her mother died in February 1901, and as the author of May Sinclair: A Modern Victorian (2000) has pointed out May Sinclair found herself suddenly "alone and free". (11)

The Divine Fire (1904), a critique of the bookselling industry, was her first major success, establishing her reputation not only in Britain, but in America, where it was a best-seller. Like much of her fiction it deals with the emotional and psychological lives of artists. A year after publication, the novel was so famous and so much admired that Sinclair embarked on a tour of the East Coast and met Ralph Waldo Emerson, Mark Twain, Annie Fields and Sarah Orne Jewett. Now a successful writer she no longer had money problems. (12)

Sinclair lost four brothers from heart failure between 1887 and 1896. When Joseph Sinclair, her last surviving brother, died in 1905, Sinclair assumed responsibility for his children, and then for those of her brother William when his widow died in 1906. By this time her mother had died and In August 1907 she took a flat at 4 The Studios, Edwardes Square, Kensington, London. Her friends included H. G. Wells, Ford Madox Ford, Percy Wyndham Lewis, and W. B. Yeats. (13)

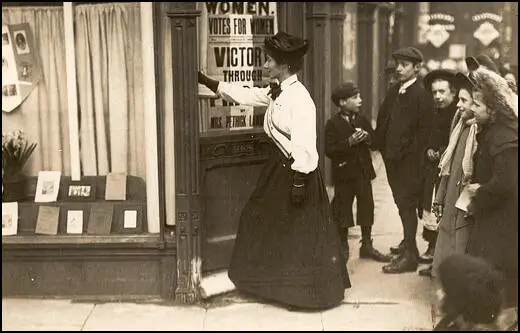

Women's Suffrage

A supporter of the women's suffrage movement, Sinclair was a member of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). On 1st March 1908 she had a letter published in Votes for Women where she said: "I can only say that it is impossible to be a woman and not admire to the utmost the devotion, the courage, and the endurance of the women who are fighting and working for Suffrage today. And I am glad and honoured to have this opportunity to recording my whole-hearted sympathy with them and with their aims." (14)

May Sinclair concentrated on novels exploring the difficulties women faced in sexual, domestic, and intellectual arenas in The Helpmate (1907), The Judgement of Eve (1907) and Kitty Tailleur (1908). The Creators (1910) a novel that dealt with the way men denigrate women's creativity. (15) It has been argued that with these novels Sinclair became "one of the few brilliant women philosophers of her time". (16)

In 1908 Cicely Hamilton formed the Women Writers Suffrage League (WWSL). The WWSL stated that its object was "to obtain the vote for women on the same terms as it is or may be granted to men. Its methods are those proper to writers - the use of the pen." Women writers who joined the organisation included May Sinclair, Beatrice Harraden, Elizabeth Robins, Charlotte Despard, Alice Meynell, Olive Schreiner, Edith Ellis, Margaret Nevinson, Evelyn Sharp and Marie Belloc Lowndes. Sympathetic male writers such as Israel Zangwill and Laurence Housman, were allowed to become "Honorary Men Associates". (17)

In October 1908 Sinclair met Thomas Hardy for the first time, and the two went cycling together, from Dorchester to Weymouth. Hardy admired Sinclair's work, and she was in turn delighted by his admiration. She told Katherine Tynan Hinkson in a letter that she had "lost her heart" to the author. (18) Later that year Sinclair met Ezra Pound and would become both his financial patron and advocate for his work. (19)

May Sinclair disapproved of the WSPU arson campaign and left the organisation and joined the Women's Freedom League (WFL). Like the WSPU, the WFL was a militant organisation that was willing the break the law. As a result, over 100 of their members were sent to prison after being arrested on demonstrations or refusing to pay taxes. However, members of the WFL was a completely non-violent organisation and opposed the WSPU campaign of vandalism against private and commercial property. Court protests against the trial of women "by man made laws", a favourite idea of Teresa Billington-Greig, were carried out by the WFL. (20)

May Sinclair and Feminism

In a letter to The Times, Britian's leading bacteriologist and immunologist, Dr. Almroth Wright argued that women were physically, intellectually, and morally inferior to men, so that to concede them the suffrage would be harmful to the state. He argued that women's brains were innately different from men's and were not constituted to deal with social and public issues. Wright also vigorously opposed the professional development of women. Wright claimed that the suffragists were powered by their sexual frustration because of the shortage of men. (21)

The Women's Freedom League asked May Sinclair to respond to Wright. The result was the pamphlet Feminism (1912): "Now, to have established his hypothesis on truly scientific lines Sir Almroth Wright should have had under his personal examination a majority, not only of the members of the Women's Social and Political Union, but of every Suffrage Society throughout the country; to say nothing of other countries, for in these, by his own showing, hysteria and a desire for the vote have not been invariably connected as agent and disease. That is to say, the 'hysteria bacillus' is not present in every case of suffragitis. And, if it is not present, what becomes of his hypothesis ? But let that pass. Sir Almroth Wright can reply that he is only investivating the British variety. And no doubt he can plead further that he has scientific precedent for his procedure. You are not bound to examine, say, every case of amoebic dysentery in order to establish the existence of entamoeba histolytica as the pathogenic germ. Enough, if you can eliminate other causes in a sufficient number of cases. True, but Sir Almroth Wright has not eliminated other causes. He has not searched for them. He is apparently unaware that they may exist. As for his cases, if he were really investigating a disease, would he not be careful to choose such only as were typical?"

Sinclair mentions friends in the movement such as Charlotte Despard, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst "among the militants, and among non-militants women like" Millicent Garrett Fawcett, Emily Davies and Frances Balfour. "They will present him with the thing he is investigating in its utmost purity and perfection. Even from the rank and file, from all grades and classes of suffrage societies the list could be prolonged indefinitely. Such women are alone representative of their movement; and if Sir Almroth Wright were to enquire closely, I think he would realise that in all of them the element of hysteria is either absent or negligible. Whoever charges such women with hysteria, neurosis, and degeneracy stands self-convicted of a lack of balance and acumen. Heaven forbid that I should pledge myself to the assertion that there are no hysterical, neurotic, or degenerate subjects in the Suffrage movement. I have one or two in my mind (as Sir Almroth Wright probably has) at this moment. The Suffrage Movement draws with a wide net, and in all large assemblies of human beings (men as well as women) you will find some neurosis and hysteria and degeneracy, neurosis being the scourge of modernity." (22)

Influence of Sigmund Freud

May Sinclair developed a love of the work of the Brontë sisters. She wrote an introduction to the new Everyman edition of Elizabeth Gaskell's, The Life of Charlotte Brontë, and the novels of Charlotte, Anne and Emily. The Three Brontës, a full length work of criticism and biography was published in 1912. (23)

In March 1913, an unknown poet, Charlotte Mew, wrote a letter to May Sinclair about her recently published The Combined Maze (1913). Sinclair replied and the two women became very close. Sinclair became her vigorous champion, encouraging her to "believe in herself and securing the publication of her poems in periodicals and in volume form and rounding up sympathetic reviewers among her friends." (24) Rebecca Bowler claims that Mew was in love with Sinclair and the two had a brief but intense friendship. (25)

In October 1913 Sinclair attended the inaugural meeting of the Medico-Psychological Clinic of London, "the first clinic in England to include psychoanalysis in an eclectic array of therapeutic methods". (26) Sinclair wrote the prospectus, and was elected as one of the twelve founder members, and as a member of the board of management. After discovering the work of Sigmund Freud she wrote the book, The Three Sisters (1914) a study of middle-class women in a repressive society. This book marked the beginning of Sinclair's interest in psychology and her attempts to explore unconscious motivation. (27)

First World War

On the outbreak of the First World War Sinclair went to France where she worked for the Motor Ambulance Unit. Sinclair was overcome by what she saw and after seventeen days she was sent home to England. Articles based on her experiences appeared in the The English Review during the summer of 1915. A fuller account, Journal of Impressions in Belgium, was published at the winter of 1915. It was among the first journals of the war written from the perspective of a woman to be published in Britain. (28)

In 1916 Sinclair was elected a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. In the same year William Lyon Phelps, of Yale University, who taught the first American university course on the modern novel, hailed her as "the foremost living writer among English-speaking women" (29)

In May 1917, May Sinclair joined forces with Louisa Garrett Anderson, Hertha Ayrton, Evelyn Sharp, Olive Schreiner, Millicent Garrett Fawcett, Elizabeth Robins, Maude Royden, Mary Macarthur, Margaret Bondfield, Esther Roper, Margaret Ashton, Susan Lawrence and Eleanor Rathbone to urge Parliament to pass the Solicitors (Qualification of Women Bill, a measure to enable women to qualify and practise as solicitors in England and Wales. (30)

Later Novels

One of her best known novels was Mary Olivier (1919). It has been claimed that it was based on her own life: "Much of her family life formed the basis of this novel: the heroine's love for her brother Mark (Frank); her struggle against the tyranny and religious orthodoxy of the mother, who rejects her daughter's love in favour of her sons; her fear of hereditary madness, alcoholism, and physical weakness; her intense, unconsummated, renounced love for several different men; and the drive to individuation and creativity seeking to escape the trammels of heredity, family, environment, society, and religion. All ontact can be read as fictionalized spiritual biography." (31)

By 1920 Sinclair was at the pinnacle of her achievement, and was described by the poet and critic, Thomas Moult, as "the most widely known woman artist in the country and America". The Life and Death of Harriett Fream (1922), a portrait of a spinster who can never escape her mother's influence and an expression of female disappointment and repression, was considered by Sinclair to be "one of the best books I have done". (32)

Later novels included Arnold Waterlow (1924), The Rector of Wyck (1925) and The Allinghams (1927). She also published two volumes of short-stories, Uncanny Stories (1923) and The Intercessor and Other Stories (1931). Suzanne Raitt has suggested that her later work "suggest that her thoughts were turning to the years ahead and to the possibility of a long, slow decline with no immediate family - no children of her own - to take care of her. She was both anticipating the petty humiliations of age and illness, and returning to the stories and characters of her past". (33)

At the time of the National Register of 1939, May Sinclair was living with her 53-year-old "Companion & Housekeeper", Florence Ada Bartrop and 30-year-old "Chauffeur & Mechanic" Ernest W. Williams at The Gables, Burcott Lane, Bierton, Buckinghamshire. (34)

May Sinclair had little contact with her friends during this period. Suffered from Parkinson's disease in the final years of her life, she disappeared from public view. She was living with her companion and housekeeper Florence Bartrop in Buckinghamshire. (35)

May Sinclair, died on 14th November 1946. She left effects valued at £10,310 3s. 9d. Harold Lumley St. Clair Sinclair (her nephew) was one of the executors of her will. (36)

Primary Sources

(1) Votes for Women (5th March 1908)

I can only say that it is impossible to be a woman and not admire to the utmost the devotion, the courage, and the endurance of the women who are fighting and working for Suffrage today. And I am glad and honoured to have this opportunity to recording my whole-hearted sympathy with them and with their aims.

(2) The Times (4 April 1912)

We are dealing less with a psychological portent than with a new sociological factor, the solidarity of women; and there is only one other factor that can be compared with it for importance, and that is the solidarity of the working man. And these two solidarities are one. For, at the bottom of it also – enthusiasm and sexless, selfless love apart – whether we like to admit it or not, are certain hard sociological and economic facts. There are more women than men in this country, and somehow those women have to be maintained. It is on the whole better for them and better for society that they should maintain themselves this that they should be ignobly or dishonestly dependent. And, even if it were not better, it has got to be. Women are driven into the labour market by the irresistible pressure, not of "physiological emergencies," but of economic forces… However much man may dislike to have women working side by side with him, he has no objection to women working side by side with him, he has no objection whatever to him her working under him, so long as her work is cheap. What he lives in fear of is that any moment her work may become dear. That is why he tries to undervalue it by his talk of "physical disabilities" and that is why he hates above all things the suffrage movement. It is, after all, as much a commercial as a sexual fear and hatred.

(3) May Sinclair, Feminism (1912)

It would seem as if almost any old argument were good enough for the man who reads the papers. You may appeal, directly, if you are crude, indirectly if you are at all subtle, to his grosser instincts, to his plentiful emotions, to the prejudices that rule him for the moment. This is the ancient argumentum ad homincm and it never fails of its effect. All that it requires is a sufficient command of journalistic rhetoric. You may handle your case against a whole class, a whole sex, by ardent generalization from a single instance, painful, intimate, domestic. You may even seem to prove your case by bringing forward all the instances that support it and suppressing all the rest. The third form of argument, when combined with the first, is, to the man who reads the papers, simply irresistible. But it cannot be said that these methods commend themselves as scientific. They are not the kind employed by Sir Almroth Wright when he set out on the great research associated with his name. I do not know whether it would be difficult to demonstrate to the man who reads the papers every link in that beautiful chain of proof by which he there established his hypothesis. When it comes to denouncing the Suffragist movement for his benefit, Sir Almroth Wright has no beautiful chain of proof to offer him at all. Nobody, of course, could suspect a man of Sir Almroth Wright's eminence of arguing from a single painful, intimate, domestic instance; but, in his extraordinary descent from the serene heights of Science into this really horrid arena, he has not scrupled to fall back upon the 1st and 3rd methods indicated above. Somewhere on the serene heights there must be angels weeping, and wondering.

As far as can be made out in the confusion of his onrush, his hypothesis is that what we may call journalistically the " hysteria bacillus " is present as the pathogenic agent in every case of what the journalists are calling "Suffragitis." Now, to have established his hypothesis on truly scientific lines Sir Almroth Wright should have had under his personal examination a majority, not only of the members of the Women's Social and Political Union, but of every Suffrage Society throughout the country; to say nothing of other countries, for in these, by his own showing, hysteria and a desire for the vote have not been invariably connected as agent and disease. That is to say, the "hysteria bacillus" is not present in every case of suffragitis. And, if it is not present, what becomes of his hypothesis ? But let that pass. Sir Almroth Wright can reply that he is only investivating the British variety. And no doubt he can plead further that he has scientific precedent for his procedure. You are not bound to examine, say, every case of amoebic dysentery in order to establish the existence of entamoeba histolytica as the pathogenic germ." Enough, if you can eliminate other causes in a sufficient number of cases.

True, but Sir Almroth Wright has not eliminated other causes. He has not searched for them. He is apparently unaware that they may exist. As for his cases, if he were really investigating a disease, would he not be careful to choose such only as were typical? And by typical, he, a man of science, would not mean what the newspaper man means - the sort of cases you see going about - but classic cases, "beautiful cases," cases which present their symptoms, not mixed with obscure and doubtful and extraneous matter, but clear and perfect and unmistakable. And for such "beautiful cases" he should look, not among the rank and file of the suffrage movement, but among its leaders, where he will find women like Mrs. Despard, and Dr. Garrett Anderson, Mrs. Pethick Lawrence, Mrs. Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst among the militants, and among non-militants women like Mrs. Fawcett, Miss Emily Davies, Lady Frances Balfour. They will present him with the thing he is investigating in its utmost purity and perfection. Even from the rank and file, from all grades and classes of suffrage societies the list could be prolonged indefinitely. Such women are alone representative of their movement; and if Sir Almroth Wright were to enquire closely, I think he would realise that in all of them the element of hysteria is either absent or negligible. Whoever charges such women with hysteria, neurosis, and degeneracy stands self-convicted of a lack of balance and acumen. Heaven forbid that I should pledge myself to the assertion that there are no hysterical, neurotic, or degenerate subjects in the Suffrage movement. I have one or two in my mind (as Sir Almroth Wright probably has) at this moment. The Suffrage Movement draws with a wide net, and in all large assemblies of human beings (men as well as women) you will find some neurosis and hysteria and degeneracy, neurosis being the scourge of modernity. Equally true is it that many women threatened or afflicted with the scourge, have found their cure in the work exacted by the suffrage leaders; and when they have found it, their medical man knows them no more.

Allowance must be made for medical men (and for medical women, for that matter). They are handicapped by the fact that their chief and most absorbing experience lies among the unhealthy. Think of the long procession of disabled and morbid women who trail for ever through their consulting rooms. No wonder that no doctor can ever lose sight of the fact that the mind of woman is always threatened with the reverberations of her physiological emergencies. "As for woman, herself," says Sir Almroth Wright, "she makes very light of any of these mental upsettings." I, for one, do not make light of them, any more than I make light of the Life-Force. I do not question its supremacy and importance. I do not for a moment question the scientific value of Sir Almroth Wright's experience. I only object to the pseudoscientific use he has made of it. A man has a right to hold any views on Women's Suffrage that he chooses, but a man of science has no right to support his views by pseudo-scientific arguments. If that is not one of the which Sir Almroth Wright invokes for his own purposes, it is one which he must observe if he is to maintain the integrity of his professional conscience. He argues as if all women were physically unhealthy, and all potentially, when not actually insane. At the bottom of the Feminist movement he finds this "clement of mental disorder"; he finds bitterness and fury, springing from the insurgence of woman's frustrated natural instincts. He argues as if there were no such thing in the world as self-control. Even in animals - I say even, because in these at least one of the sexes has periods of complete quiescence - male and female cannot be worked side by side." Every woman should be clearly told - and the woman of the world will immediately understand - that when man sets his face against the proposal to bring in an epicene world he does so because he can do his best work only in surroundings where he is perfectly free from suggestion and restraint." In the same spirit he charges medical women with lack of modesty and reticence.

Student Activities

References

(1) David Simkin, Family History Research (14th November, 2022)

(2) Suzanne Raitt, May Sinclair: A Modern Victorian (2000) page 19

(3) May Sinclair, letter to Katherine Tynan Hinkson (14th April, 1912)

(4) Max Saunders, May Sinclair: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (4th January 2007)

(5) Theophilus Boll, Miss May Sinclair: Novelist (1973) page 33

(6) Suzanne Raitt, May Sinclair: A Modern Victorian (2000) page 26

(7) Rebecca Bowler, May Sinclair (November, 2022)

(8) Max Saunders, May Sinclair: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (4th January 2007)

(9) Rebecca Bowler, May Sinclair (November, 2022)

(10) Theophilus Boll, Miss May Sinclair: Novelist (1973) page 169

(11) Suzanne Raitt, May Sinclair: A Modern Victorian (2000) page 83

(12) Rebecca Bowler, May Sinclair (November, 2022)

(13) Max Saunders, May Sinclair: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (4th January 2007)

(14) Votes for Women (5th March 1908)

(15) Max Saunders, May Sinclair: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (4th January 2007)

(16) Suzanne Raitt, May Sinclair: A Modern Victorian (2000) page 42

(17) Elizabeth Crawford, The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928 (2000) page 638

(18) May Sinclair, letter to Katherine Tynan Hinkson (15th October, 1908)

(19) Rebecca Bowler, May Sinclair (November, 2022)

(20) Teresa Billington Greig, The Non-Violent Militant: Selected Writings of Teresa Billington-Greig (1987) page 107

(21) The Times (28 March 1912)

(22) May Sinclair, Feminism (1912)

(23) Rebecca Bowler, May Sinclair (November, 2022)

(24) Theophilus Boll, Miss May Sinclair: Novelist (1973) page 103

(25) Rebecca Bowler, May Sinclair (November, 2022)

(26) Theophilus Boll, Miss May Sinclair: Novelist (1973) page 104

(27) Max Saunders, May Sinclair: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (4th January 2007)

(28) Rebecca Bowler, May Sinclair (November, 2022)

(29) The Times (15th November, 1946)

(30) Votes for Women (4th May 1917)

(31) Max Saunders, May Sinclair: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (4th January 2007)

(32) Theophilus Boll, Miss May Sinclair: Novelist (1973) page 143

(33) Suzanne Raitt, May Sinclair: A Modern Victorian (2000) page 241

(34) National Register (1939)

(35) Rebecca Bowler, May Sinclair (November, 2022) (28)