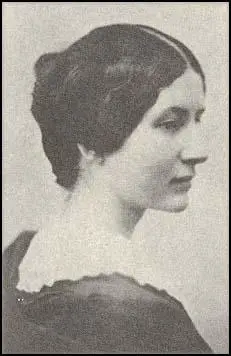

Annie Fields

Annie Adams, the sixth of seven children, was born in Boston on 6th June, 1834. Her father, Zabdiel Boylston Adams, was a doctor. According to her biographer, Susan K. Harris: "like most American women from wealthy and educated homes in the Northeast, Annie Adams was educated both at home and at school. George B. Emerson's School for Young Ladies stressed study in science, history, foreign languages (including Latin)."

As a teenager she met James Thomas Fields, a successful publisher whose 18-year old wife Eliza Willard, had died from tuberculosis in 1850. The couple were married in 1854. Annie Fields was also a writer and played an important role in her husband's company, Ticknor and Fields and helped establish a literary salon at their home at 37 Charles Street. A supporter of women's rights she encouraged women writers such as Harriet Beecher Stowe, Lydia Maria Child, Sarah Orne Jewett, Mary Freeman, and Emma Lazarus. She also became friends with other writers such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, John Greenleaf Whittier, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

In July, 1859, Annie and her husband visited Charles Dickens at Gad's Hill Place and met the famous novelist, Wilkie Collins: "Early in the month of July, 1859, I spent a day with him in his beautiful country retreat in Kent. He drove me about the leafy lanes in his basket wagon, pointing out the lovely spots belonging to his friends, and ending with a visit to the ruins of Rochester Castle. We climbed up the time-worn walls and leaned out of the ivied windows, looking into the various apartments below. I remember how vividly he reproduced a probable scene in the great old banqueting-room, and how graphically he imagined the life of ennui and everyday tediousness that went on in those lazy old times. I recall his fancy picture of the dogs stretched out before the fire, sleeping and snoring with their masters. That day he seemed to revel in the past, and I stood by, listening almost with awe to his impressive voice, as he spoke out whole chapters of a romance destined never to be written. On our way back to Gad's Hill Place, he stopped in the road, I remember, to have a crack with a gentleman who he told me was a son of Sydney Smith. The only other guest at his table that day was Wilkie Collins; and after dinner we three went out and lay down on the grass, while Dickens showed off a raven that was hopping about, and told anecdotes of the bird and of his many predecessors." Annie commented that Dickens impressed her with his the "exquisite delicacy and quickness of his perception, something as fine as the finest woman possesses".

Fields was a supporter of Abraham Lincoln during the American Civil War and wanted a complete end to slavery. As Susan K. Harris, the author of The Cultural Work of the Late Nineteenth-Century Hostess (2004), has pointed out: "With most of her New England contemporaries, she was a political liberal, especially when it came to social reform: a staunch abolitionist during the Civil War, she attended meetings of the Freedmen's Association after the war's conclusion, and seems to have been peripherally involved with the move to send teachers to the South."

James T. Fields tried to encourage Dickens to carry out a reading tour of the United States. On 22nd May, 1866, he wrote to reject the suggestion: "Your letter is an excessively difficult one to answer, because I really do not know that any sum of money that could be laid down would induce me to cross the Atlantic to read. Nor do I think it likely that any one on your side of the great water can be prepared to understand the state of the case. For example, I am now just finishing a series of thirty readings. The crowds attending them have been so astounding, and the relish for them has so far outgone all previous experience, that if I were to set myself the task, 'I will make such or such a sum of money by devoting myself to readings for a certain time,' I should have to go no further than Bond Street or Regent Street, to have it secured to me in a day. Therefore, if a specific offer, and a very large one indeed, were made to me from America, I should naturally ask myself, 'Why go through this wear and tear, merely to pluck fruit that grows on every bough at home?' It is a delightful sensation to move a new people; but I have but to go to Paris, and I find the brightest people in the world quite ready for me. I say thus much in a sort of desperate endeavor to explain myself to you. I can put no price upon fifty readings in America, because I do not know that any possible price could pay me for them. And I really cannot say to any one disposed towards the enterprise, 'Tempt me,' because I have too strong a misgiving that he cannot in the nature of things do it."

Dickens eventually changed his mind and on 9th November, 1867, he left Liverpool on board the Cuba and following a rough passage, arrived in Boston ten days later. Fields later recalled: "A few of his friends, under the guidance of the Collector of the port, steamed down in the custom-house boat to welcome him. It was pitch dark before we sighted the Cuba and ran alongside. The great steamer stopped for a few minutes to take us on board, and Dickens's cheery voice greeted me before I had time to distinguish him on the deck of the vessel. The news of the excitement the sale of the tickets to his readings had occasioned had been earned to him by the pilot, twenty miles out. He was in capital spirits over the cheerful account that all was going on so well, and I thought he never looked in better health. The voyage had been a good one, and the ten days' rest on shipboard had strengthened him amazingly he said. As we were told that a crowd had assembled in East Boston, we took him in our little tug and landed him safely at Long Wharf in Boston, where carriages were in waiting. Rooms had been taken for him at the Parker House, and in half an hour after he had reached the hotel he was sitting down to dinner with half a dozen friends, quite prepared, he said, to give the first reading in America that very night, if desirable. Assurances that the kindest feelings towards him existed everywhere put him in great spirits, and he seemed happy to be among us."

On 21st November, 1867, James and Annie gave Dickens a dinner at their home, 37 Charles Street. His biographer, Peter Ackroyd, has commented: "James Fields, and his wife Annie Adams Fields... became his closest friends during the visit, Annie herself being then thirty-three while her husband was fifty." Dickens described Annie to Mamie Dickens as "a very nice woman, with a rare relish for humour and a most contagious laugh". Annie wrote in her diary that Dickens "bubbled over with fun" at the dinner and that he often "convulsed the company with laughter with... his queer turns of expression". She added that she was very lucky "to have known this great man so well." Dickens told Mamie that: "They are the most devoted friends, and never in the way, and never out of it." Michael Slater has argued: "Not only did the Fieldes provide him with a congenial domestic base (he actually stayed a few days in their house in early January, breaking his otherwise cast-iron rule about never accepting private hospitality during his reading tours), they also offered him an intimate and admiring friendship, firmly based upon their love for him as a great and good man and upon their unbounded admiration for his artistic genius."

James and Annie Fields visited England in May, 1868. Charles Dickens took a suite for himself in the St James's Hotel in Piccadilly in order to show them the sights of London, Windsor and Richmond. The couple also visited Gad's Hill Place and met Georgina Hogarth, Kate Dickens and Mamie Dickens. Fields later commented: "There is no prettier place than Gad's Hill in all England for the earliest and latest flowers, and Dickens chose it, when he had arrived at the fullness of his fame and prosperity, as the home in which he most wished to spend the remainder of his days." Annie wrote in her diary: "I never saw anything prettier; Kate with her muslin kerchief... with white hollyhocks in her hair and her quaint graceful little figure and he (Dickens), light and lithe as a boy of 20 - those two take great delight in each other."

Dickens was very open about his problems as a father and mother. Annie recorded, that he was "often troubled by the lack of energy his children show and has even allowed James to see how deep his unhappiness is in having so many children by a wife who is totally uncongenial." Although they did not meet Ellen Ternan he did tell James about her existence. This information was passed on to Annie. She wrote in her diary: "I feel the bond there is between us. She must feel it too. I wonder if we shall ever meet."

On her return to Boston she began a regular correspondence with Georgina Hogarth. In February 1870, she wrote in her diary: "Nobody can say how much too much of this the children have to bear and to how little purpose poor Miss Hogarth spends her life hoping to comfort and care for him. I never felt more keenly her anomalous and unnatural position in the household. Not one mentioned her name; they could not have, I suppose, lest they might do her wrong. Ah, how sad a name it must be to those who love him best. Dear, dear Dickens."

Annie took a strong interest in social reform and in 1870 founded the Holly Tree Inn in Chicago. The name was taken from a short-story, The Boots at the Holly Tree Inn , by Charles Dickens. According to Rita K. Gollin, the author of Annie Adams Fields, Woman of Letters (2002), they were intended to “provide substantial food at cost prices” to working women. The Boston Globe, reported on 14th December, 1872, that “an average of two-thirds of those who avail themselves of the privileges are persons who do not really need to economize, while one-third, consisting of milliners, shop-girls, etc. live at the place from motives of economy, and save fully two-thirds in board.”

Annie Fields wrote about her social work in How to Help the Poor (1883): "The management of the organization in Boston is vested in a board of twenty-two directors, ladies and gentlemen, who meet always once a month, and more frequently in emergencies.... The district office may be called the home of the agent. Here duplicate registration cards of reference are kept respecting the poor of the district; here information may be found about persons needing employment, especially that of men and children who can work only a part of the time, and therefore cannot be advertised or sent to an intelligence office. These offices are arms, as it were, of the Industrial Aid Society, which may be called a kind of central bureau for employment of this nature. Here the volunteer visitors may find the agent any day, or meet each other at the regular meetings called conferences, which occur weekly."

James Thomas Fields died on 24th April, 1881. Soon afterwards Sarah Orne Jewett moved in with Annie. Mark DeWolfe Howe has argued in Memories of a Hostess (1922): "James Fields chose Jewett as the ideal friend to fill the impending gap in the life of his wife. He must have known that, when the time should come for readjusting herself to life without him, she would need something more than random contacts with friends ... He must have realized that the intensely personal element in her nature would require an outlet through an intensely personal devotion. If he could have foreseen the relation that grew up between Mrs. Fields and Miss Jewett her junior by about fifteen years almost immediately upon his death, and continued throughout the life of the younger friend, he would surely have felt a great security of satisfaction in what was yet to be."

When the women were apart they wrote passionate letters to each other. In March 1882, Sarah wrote: "Are you sure you know how much I love you... I think of you and think of you and I am always reminded of you." In another letter she told Annie: "I long to see you and say all sorts of foolish things... and to kiss you ever so many times." Lillian Faderman, the author of Surpassing the Love of Men (1981) openly suggest that Fields and Jewett's relationship was lesbian. However, others have raised doubts about this.

In 1884 George Washington Cable visited their home: "In Charles Street I dined and spent the evening with Mrs. Fields and Miss Sarah Orne Jewett. They are both women of emphatic goodness and intelligence. Mrs. Fields could not see me for some time as she had just come in from a hard day's work of visiting her various charities and was bedraggled by the storm. we talked of men and things... It helps anecdotes, to hear them from a lovely woman of mind & heart & good works & fame, and golden years, and black hair waving down from the centre of the upper forehead & backward to the ears. I must try to get her picture... Miss Jewett is not picturesque, like Mrs Fields, but it's a sweet short sermon just to look at her."

Annie now concentrated on writing and published a book on John Greenleaf Whittier entitled, Whittier, Notes of His Life and of His Friendship (1883). This was followed by book social welfare reform, How to Help the Poor (1883). Other books by Fields include: A Shelf of Old Books (1894), The Singing Shepherd, and Other Poems (1895), and biographies of Harriet Beecher Stowe and Nathaniel Hawthorne entitled Life and Letters of Harriet Beecher Stowe (1897) and Nathaniel Hawthorne (1899).

According to Henry James Annie retained her interest in new writers: "She herself had the good fortune to assist, during all her later years, at an excellent case of such growth, for which nature not less than circumstance had perfectly fitted her - she was so intrinsically charming a link with the past and abounded so in the pleasure of reference and the grace of fidelity. She helped the present, that of her own actuality, to think well of her producing conditions, to think better of them than of many of those that open for our wonderment today: what a note of distinction they were able to contribute, she moved us to remark, what a quality of refinement they appeared to have encouraged, what a minor form of the monstrous modern noise they seemed to have been consistent with!"

In 1902 Sarah Orne Jewett was thrown from a carriage and injured her head and neck. The injuries caused her recurring pain, dizziness, and forgetfulness over the next four years. As Susan K. Harris, the author of The Cultural Work of the Late Nineteenth-Century Hostess (2004), has pointed out: "While Jewett was recuperating in Maine, Fields suffered a mild stroke in Boston; the result of both their illnesses was a prolonged separation and resultant anxiety about each other."

Annie Fields died on 5th January, 1915.

Primary Sources

(1) Annie Fields, diary entry (February, 1870)

Nobody can say how much too much of this the children have to bear and to how little purpose poor Miss Hogarth spends her life hoping to comfort and care for him. I never felt more keenly her anomalous and unnatural position in the household. Not one mentioned her name; they could not have, I suppose, lest they might do her wrong. Ah, how sad a name it must be to those who love him best. Dear, dear Dickens.

(2) Susan K. Harris, The Cultural Work of the Late Nineteenth-Century Hostess (2004)

Between these two houses, Annie Fields entertained the array of American and British writers of her time, as well as a scattering of politicians, musicians, actors, artists, and social reformers. With most of her New England contemporaries, she was a political liberal, especially when it came to social reform: a staunch abolitionist during the Civil War, she attended meetings of the Freedmen's Association after the war's conclusion, and seems to have been peripherally involved with the move to send teachers to the South. She supported a strong government, comforting herself after Lincoln's assassination by noting that " True hearted men and women are not cast down, they rather see a happy reward for our noble President and the stronger hand of Andrew Johnson is what we need now, all believe." She also devoted a substancial part of her life to charity work anion, the Boston poor, establishing coffee houses (as alternatives to bars) and residences for single womcn, and participating in the move to professionalize charitable agencies.

(3) Arthur A. Adrian, Georgina Hogarth and the Dickens Circle (1957)

As her friendship with Annie deepened through the years, Georgina's closely written pages became increasingly intimate and revealing. And Mrs. Fields often meditated on her friend, on Dickens's daughters, and on life at Gad's Hill. But dimming the joy of her first memories was the persistent conviction of an ominous shadow over that household. On the second anniversary of her 1869 visit, reflecting on a recent entertainment in her own home, she confided to her diary that there had been "more jollity than ever I saw except at Dickens's, and alas! I must say it, with more real lightness of heart than I ever saw at Gad's Hill. The shadow of somewhere already fallen there and there were no young people - young in the sense of being innocent of all experience as these are here."

(4) Annie Fields, lecture (1882)

Everywhere... good men are listening and pondering on these things. Henry George seems to have a larger following in England than he has in this country - perhaps he is right - perhaps he has found one means for the solution of the evil - if so where so likely to begin a trial of his ideas as in some part of England.

(5) Annie Fields, How to Help the Poor (1883)

Visiting the poor does not mean entering the room of a person hitherto unknown, to make a call. It means that we are invited to visit a miserable abode for the purpose first of discovering the cause of that misery. A physician is sometimes obliged to see a case many times before the nature of the disease is made clear to his mind; but, once discovered, he can prescribe the remedy.

(6) Annie Fields, How to Help the Poor (1883)

The management of the organization in Boston is vested in a board of twenty-two directors, ladies and gentlemen, who meet always once a month, and more frequently in emergencies. In this number are included the Chairman of the Overseers of the Poor, the President of the Boston Provident Association, the President of the Society of St. Vincent de Paul and of the Roxbury Charitable Society. The other members are persons chosen because they are known to have done or tried to do some practical labor for the poor, as well as because of their intelligent interest in the subject.

The district office may be called the home of the agent. Here duplicate registration cards of reference are kept respecting the poor of the district; here information may be found about persons needing employment, especially that of men and children who can work only a part of the time, and therefore cannot be advertised or sent to an intelligence office. These offices are arms, as it were, of the Industrial Aid Society, which may be called a kind of central bureau for employment of this nature. Here the volunteer visitors may find the agent any day, or meet each other at the regular meetings called conferences, which occur weekly.

The agent becomes a connecting link for the volunteer visitors who come daily for advice and assistance. When a family is in distress of any kind, there need be no delay in getting relief, because the agent is always ready to consult with the committee, if necessary, or is able by constant experience to know how and what to do immediately.

The struggle of the volunteer visitors under the various district committees has been a brave one, and the exhortation "to give to him that asketh" is at length bearing fruit; but it is slow fruition, because there must be growth; and, if such work is to be really useful, the service of many persons must be accepted whose work is necessarily intermittent. "This must be done in order that we may secure a sufficient number of workers, and not waste, but gather in and use, all the overflowing sympathy which is such a blessing to giver and receiver. With our volunteers, home-claims must and should come first; and it is precisely those whose claims are deepest and whose family life is the noblest who have the most precious influence in the homes of the poor. But, if the work is to be valuable, we must find some way to bind together those broken scraps of time, and thus give it continuity in spite of changes and breaks."

This we believe we have done in establishing agents in every district who are assisted each by a committee of men and women. Certainly agents and committees are yet very far from understanding the full scope of their work, but knowledge is increasing every day, and the reform is moving on because the foundations are sound.

One great difficulty in advancing any public work of such unobtrusive character is that of finding a sufficient number of unselfish persons who will take hold of it. "I believe that educated people would come forward, if once they saw how they could be really useful and without neglecting nearer claims. Let us reflect that hundreds of workers are wanted; that, if they are to preserve their vigor, they must not be overworked; and that each of us that might help and holds back not only leaves work undone, but injures to a certain extent the work of others. Let each of us not attempt too much, but take some one little bit of work and, doing it simply, thoroughly, and lovingly, wait patiently for the gradual spread of good." In our present method of helping the poor by associated and organized labor, it is found that a little time will go a great way. Two hours a week on an average, the year through, is all the time that need be given by a visitor who is busied with other duties and yet wishes to do something to help the unfortunate. Within this brief space of time, more good can be achieved than is easy to describe; and who cannot save two hours for such a work? I know many persons give more time because it is theirs to bestow, and because their interest grows and thrusts aside other things; but this is no reason why others should withhold the mite they possess.

(7) Henry James, Atlantic Monthly (July 1915)

It was not perhaps in the purest gold of the matter that we pretended to deal in the New York and the Boston to which I have referred; but if I wish to catch again the silver tinkle at least, straining my ear for it through the sounds of today, I have but to recall the dawn of those associations that seemed then to promise everything, and the last declining ray of which rests, just long enough to be caught, on the benign figure of Mrs. Fields, of the latter city, recently deceased and leaving behind her much of the material out of which legend obligingly grows. She herself had the good fortune to assist, during all her later years, at an excellent case of such growth, for which nature not less than circumstance had perfectly fitted her - she was so intrinsically charming a link with the past and abounded so in the pleasure of reference and the grace of fidelity. She helped the present, that of her own actuality, to think well of her producing conditions, to think better of them than of many of those that open for our wonderment today: what a note of distinction they were able to contribute, she moved us to remark, what a quality of refinement they appeared to have encouraged, what a minor form of the monstrous modern noise they seemed to have been consistent with!

The truth was of course very decidedly that the seed I speak of, the seed that has flowered into legend, and with the thick growth of which her domestic scene was quite embowered, had been sown in soil peculiarly grateful and favored by pleasing accidents. The personal beauty of her younger years, long retained and not even at the end of such a stretch of life quite lost; the exquisite native tone and mode of appeal, which anciently we perhaps thought a little 'precious,' but from which the distinctive and the preservative were in time to be snatched, a greater extravagance supervening; the signal sweetness of temper and lightness of tact, in fine, were things that prepared together the easy and infallible exercise of what I have called her references. It adds greatly to one's own measure of the accumulated years to have seen her reach the age at which she could appear to the younger world about her to 'go back' wonderfully far, to be almost the only person extant who did, and to owe much of her value to this delicate aroma of antiquity.

My title for thus speaking of her is that of being myself still extant enough to have known by ocular and other observational evidence what it was she went back to and why the connection should consecrate her. Every society that amounts, as we say, to anything has it own annals, and luckless any to which this cultivation of the sense of a golden age that has left a precious deposit happens to be closed. A local present of proper pretensions has in fact to invent a set of antecedents, something in the nature of an epoch either of giants or of fairies, when literal history may in this respect have failed it, in order to look other temporal claims of a like complexion in the face. Boston, all letterless and unashamed as she verily seems today, needs luckily, for recovery of self-respect, no resort to such make-believes - to legend, that is, before the fact; all her legend is well after it, absolutely upon it, the large, firm fact, and to the point of covering, and covering yet again, every discernible inch of it. I felt myself during the half-dozen years of my younger time spent thereabouts just a little late for history perhaps, though well before, or at least well abreast of, poetry; whereas now it all densely foreshortens, it positively all melts beautifully together, and I square myself in the state of mind of an authority not to be questioned. In other words, my impression of the golden age was a first-hand one, not a second or a third; and since those with whom I shared it have dropped off one by one, - I can think of but two or three of the distinguished, the intelligent and participant, that is, as left, - I fear there is no arrogance of authority that I am not capable of taking on.

James T. Fields must have had about him when I first knew him much of the freshness of the season, but I remember thinking him invested with a stately past; this as an effect of the spell cast from an early, or at least from my early, time by the 'Ticknor, Reed and Fields' at the bottom of every title-page of the period that conveyed, however shyly, one of the finer presumptions. I look back with wonder to what would seem a precocious interest in title-pages, and above all into the mysterious or behind-the-scenes world suggested by publishers' names – which, in their various collocations, had a color and a character beyond even those of authors, even those of books themselves; an anomaly that I seek not now to fathom, but which the brilliant Mr. Fields, as I aspiringly saw him, had the full benefit of, not less when I first came to know him than before. Mr. Reed, Mr. Ticknor, were never at all to materialize for me; the former was soon to forfeit any pertinence, and the latter, so far as I was concerned, never so much as peeped round the titular screen. Mr. Fields, on the other hand, planted himself well before that expanse; not only had he shone betimes with the reflected light of Longfellow and Lowell, of Emerson and Hawthorne and Whittier, but to meet him was, for an ingenuous young mind, to find that he was understood to return with interest any borrowed glory and to keep the social, or I should perhaps rather say the sentimental, account straight with each of his stars. What he truly shed back, of course, was a prompt sympathy and conver- sability; it was in this social and personal color that he emerged from the mere imprint, and was alone, I gather, among the American publishers of the time in emerging. He had a conception of possibilities of relation with his authors and contributors that I judge no other member of his body in all the land to have had; and one easily makes out for that matter that his firm was all but alone in improving, to this effect of amenity, on the crude relation – crude, I mean, on the part of the author. Few were our native authors, and the friendly Boston house had gathered them in almost all: the other, the New York and Philadelphia houses (practically all we had) were friendly, I make out at this distance of time, to the public in particular, whose appetite they met to abundance with cheap reprints of the products of the London press, but were doomed to represent in a lower, sometimes indeed in the very lowest, degree the element of consideration for the British original. The British original had during that age been reduced to the solatium of publicity pure and simple; knowing, or at least presuming, that he was read in America by the fact of his being appropriated, he could himself appropriate but the complacency of this consciousness.

To the Boston constellation then almost exclusively belonged the higher complacency, as one may surely call it, of being able to measure with some closeness the good purpose to which they glittered. The Fieldses could imagine so much happier a scene that the fond fancy they brought to it seems to flush it all, as I look back, with the richest tints. I so describe the sweet influence because by the time I found myself taking more direct notice the singularly graceful young wife had become, so to speak, a highly noticeable feature; her beautiful head and hair and smile and voice (we wonder if a social circle worth naming was ever ruled by a voice without charm of quality) were so many happy items in a general array. Childless, what is vulgarly called unencumbered, addicted to every hospitality and every benevolence, addicted to the cultivation of talk and wit and to the ingenious multiplication of such ties as could link the upper half of the title-page with the lower, their vivacity, their curiosity, their mobility, the felicity of their instinct for any manner of gathered relic, remnant or tribute, conspired to their helping the 'literary world' roundabout to a self-consciousness more fluttered, no doubt, yet also more romantically resolute.

To turn attention from any present hour to a past that has become distant is always to have to look through overgrowths and reckon with perversions; but even so the domestic, the waterside museum of the Fieldses hangs there clear to me; their salon positively, so far as salons were in the old Puritan city dreamed of by -- which I mean allowing for a couple of exceptions not here to be lingered on. We knew in those days little of collectors; the name of the class, however, already much impressed us, and in that long and narrow drawing-room of odd dimensions -- unfortunately somewhat sacrificed, I frankly confess, as American drawing-rooms are apt to be, to its main aperture or command of outward resonance -- one learned for the first time how vivid a collection might be. Nothing would reconcile me at this hour to any attempt to resolve back into its elements the brave effect of the exhibition, in which the inclusive range of 'old' portrait and letter, of old pictorial and literal autograph and other material gage or illustration, of old original edition or still more authentically consecrated current copy, disposed itself over against the cool sea-presence of the innermost great basin of Boston's port. Most does it come to me, I think, that the enviable pair went abroad with freedom and frequency, and that the inscribed and figured walls were a record of delightful adventure, a display as of votive objects attached by restored and grateful mariners to the nearest shrine. To go abroad, to be abroad (for the return thence was to the advantage, after all, only of those who could not so proceed) represented success in life, and our couple were immensely successful.

(8) Susan K. Harris, The Cultural Work of the Late Nineteenth-Century Hostess (2004)

After James T. Fields's death in 1881, Annie Fields and Sarah Orne Jewett very quickly became a couple in the New England landscape. Opinions about this relationship vary. For their contemporaries, it seems to have been regarded as a fortunate solution to potential loneliness for both women; this is especially evident in condolence letters written to Fields on Jewett's death in 1909... Mark DeWolfe Howe, whose Memories of a Hostess (1922) constructed the image of Annie Fields for most twentieth-century readers, suggests that James Fields engineered the relationship when he realized he was about to die. Read retrospectively, Howe's construal of James Fields's part in Annie Fields and Jewett's friendship makes the role seem paternalistic, but I suspect Howe's framing was a deliberately ingenuous way of negotiating the facts of the relationship and the growing homophobia of his own era. It would be many years before Lillian Faderman (Surpassing the Love of Men, 1981) would openly suggest that Fields and Jewett's relationship was lesbian. Among recent commentators, Rita Gollin remarks that their "deeply affectionate association resists labeling," and Paula Blanchard treats it as a mutually sustaininb, sororal/maternal friendship between equals.

(9) Mark DeWolfe Howe, Memories of a Hostess (1922)

James Fields chose Jewett as the ideal friend to fill the impending gap in the life of his wife. He must have known that, when the time should come for readjusting herself to life without him, she would need something more than random contacts with friends ... He must have realized that the intensely personal element in her nature would require an outlet through an intensely personal devotion. If he could have foreseen the relation that grew up between Mrs. Fields and Miss Jewett her junior by about fifteen years almost immediately upon his death, and continued throughout the life of the younger friend, he would surely have felt a great security of satisfaction in what was yet to be.