On this day on 5th April

On this day in 1847 Chartist leader George Binns dies of consumption. George Binns, the son of a draper, was born in Sunderland on 6th December, 1815. George's parents were Quakers and he was educated at Ackworth School in Yorkshire. After serving his apprenticeship at his father's shop he worked in a drapers in Wakefield.

In 1837 both of his parents died and George Binns returned to Sunderland to take over the family's draper shop. By this time Binns had developed radical political views and with the help of his friend, James Williams, he established a Mechanics' Institute where local people could read newspapers such as The Poor Man's Guardian, The Gauntlet and The Northern Star.

For a while the two men shared the role of librarian at the Mechanics' Institute but in October they set up business as Booksellers, Stationers and Newspaper Agents at 9 Bridge Street, Sunderland. The shop sold books and newspapers and also served as a meeting place for Radicals in the town. Binns and Williams formed the Sunderland Democratic Association and the men worked closely with other Chartist organizations in the North East of England.

George Binns said at a meeting in Sunderland: "Eighteen hundred years ago the simple and sublime doctrine of equality was preached and taught and acted upon, but that doctrine has long been lost sight of, and now we see nothing but unchristian selfishness. The tyrants might boast of numbers and energy. The tyrants might array their cruelty, but the people will oppose with bravery. We are bound together with no selfish tie, they might boast of their Wellingtons, but we have a God."

Binns was a supporter of William Lovett and the Moral Force Chartists. In April 1839 Binns wrote an angry letter to the Sunderland Herald after it suggested that he had made a speech in favour of Feargus O'Connor and the Physical Force Chartists. The Sunderland magistrates were unconvinced and on 22nd July 1839, Binns and Williams were arrested and charged with attending illegal meetings and publishing a seditious handbill.

At their trial in July, 1840, both men were found guilty of attending an illegal meeting and were sentenced to six months imprisonment in Durham Gaol. George Binns and James Williams were released in January 1841. Chartists in the North East met the men at the gates of the prison and after a public meeting in Durham the men marched back to Sunderland.

After his release from Durham Gaol, George Binns returned to his drapery business. He continued to speak and work for universal suffrage and in 1841 was nominated as the Chartist parliamentary candidate for Sunderland. The Liberal candidate was Viscount Howick, the son of Earl Grey, the man responsible for the 1832 Reform Act. Afraid of splitting the vote of the reformers, Binns withdrew. Binns contributed to Viscount Howick's victory by announcing that the Tory candidate had offered him a £125 bribe to stand in the election.

George Binns's drapery business was not successful and in May 1842 he was arrested and sent to Durham Gaol after being able to pay his debts. After his release from prison Binns decided to emigrate to New Zealand. On 1st August, 1842 he sailed from Gravesend and arrived at Nelson, New Zealand, on 14th December, 1842. In New Zealand George Binns worked as an accountant (1844), clerk (1845), and baker (1846-47). George Binns died of consumption on 5th April, 1847.

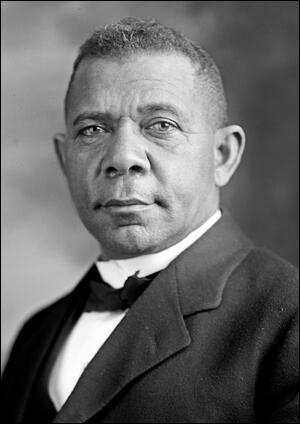

On this day in 1856 Booker Taliaferro was born a mulatto slave in Franklin Country. His father was an unknown white man and his mother, the slave of James Burroughs, a small farmer in Virginia. Later, his mother married the slave, Washington Ferguson. When Booker entered school he took the name of his stepfather and became known as Booker T. Washington.

After the Civil War the family moved to Malden, West Virginia. Ferguson worked in the salt mines and at the age of nine Booker found employment as a salt-packer. A year later he became a coal miner (1866-68) before going to work as a houseboy for the wife of Lewis Ruffner, the owner of the mines. She encouraged Booker to continue his education and in 1872 he entered the Hampton Agricultural Institute.

The principal of the institute was Samuel Armstrong, an opponent of slavery who had been commander of African American troops during the Civil War. Armstrong believed that it was important that the freed slaves received a practical education. Armstrong was impressed with Washington and arranged for his tuition to be paid for by a wealthy white man.

Armstrong became Washington's mentor. Washington described Armstrong in his autobiography as "a great man - the noblest rarest human being it has ever been my privilege to meet". Armstrong's views of the development of character and morality and the importance of providing African Americans with a practical education had a lasting impact on Washington's own philosophy.

After graduating from the Hampton Agricultural Institute in 1875 Washington returned to Malden and found work with a local school. After a spell as a student at Wayland Seminary in 1878 he was employed by Samuel Armstrong to teach in a program for Native Americans.

In 1880, Lewis Adams, a black political leader in Macon County, agreed to help two white Democratic Party candidates, William Foster and Arthur Brooks, to win a local election in return for the building of a Negro school in the area. Both men were elected and they then used their influence to secure approval for the building of the Tuskegee Institute.

Samuel Armstrong, principal of the successful Hampton Agricultural Institute, was asked to recommend a white teacher to take charge of this school. However, he suggested that it would be a good idea to employ Washington instead.

The Tuskegee Negro Normal Institute was opened on the 4th July, 1888. The school was originally a shanty building owned by the local church. The school only received funding of $2,000 a year and this was only enough to pay the staff. Eventually Washington was able to borrow money from the treasurer of the Hampton Agricultural Institute to purchase an abandoned plantation on the outskirts of Tuskegee and built his own school.

The school taught academic subjects but emphasized a practical education. This included farming, carpentry, brickmaking, shoemaking, printing and cabinetmaking. This enabled students to become involved in the building of a new school. Students worked long-hours, arising at five in the morning and finishing at nine-thirty at night.

By 1888 the school owned 540 acres of land and had over 400 students. Washington was able to attract good teachers to his school such as Olivia Davidson , who was appointed assistant principal, and Adella Logan. Washington's conservative leadership of the school made it acceptable to the white-controlled Macon County. He did not believe that blacks should campaign for the vote, and claimed that blacks needed to prove their loyalty to the United States by working hard without complaint before being granted their political rights.

Southern whites, who had previously been against the education of African Americans, supported Washington's ideas as they saw them as means of encouraging them to accept their inferior economic and social status. This resulted in white businessmen such as Andrew Carnegie and Collis Huntington donating large sums of money to his school.

In September, 1895, Washington became a national figure when his speech at the opening of the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta was widely reported by the country's newspapers. Washington's conservative views made him popular with white politicians who were keen that he should become the new leader of the African American population. To help him in this President William McKinley visited the Tuskegee Institute and praised Washington's achievements.

In 1901, President Theodore Roosevelt invited Washington to visit him in the White House. To southern whites this was going too far. One editor wrote: "With our long-matured views on the subject of social intercourse between blacks and whites, the least we can say now is that we deplore the President's taste, and we distrust his wisdom."

Washington now spent most of his time on the lecture circuit. His African American critics who objected to the way Washington argued that it was the role of blacks to serve whites, and that those black leaders who demanded social equality were political extremists.

In 1900 Washington helped establish the National Negro Business League. Washington, who served as president, ensured that the organization concentrated on commercial issues and paid no attention to questions of African American civil rights. To Washington, the opportunity to earn a living and acquire property was more important than the right to vote. Like those who helped fund the Tuskegee Institute, Washington was highly critical of the emerging trade union movement in the United States.

Washington worked closely with Thomas Fortune, the owner of The New York Age. He regularly supplied Fortune with news stories and editorials favourable to himself. When the newspaper got into financial difficulties, Washington became secretly one of its principal stockholders.

Washington's autobiography was published in The Outlook magazine and was eventually published as Up From Slavery in 1901. His critics argued that the views expressed in his books, articles and lectures were essentially the prevailing views of white Americans.

In 1903 William Du Bois joined the attack on Washington with his essay on his work in The Soul of Black Folks. Washington retaliated with criticisms of Du Bois and his Niagara Movement. The two men also clashed over the establishment of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) in 1909.

The following year, William Du Bois and twenty-two other prominent African Americans signed a statement claiming: "We are compelled to point out that Mr. Washington's large financial responsibilities have made him dependent on the rich charitable public and that, for this reason, he has for years been compelled to tell, not the whole truth, but that part of it which certain powerful interests in America wish to appear as the whole truth."

Although he now had a large number of critics, Washington continued to be consulted by powerful white politicians and had a say in the African American appointments made by Theodore Roosevelt (1901-09) and William H. Taft (1909-13).

Booker T. Washington was taken ill and entered St. Luke's Hospital, New York City, on 5th November, 1915. Suffering from arteriosclerosis he was warned that he did not have long to live. He decided to travel to Tuskegee where he died on 14th November. Over 8,000 people attended his funeral held in the Tuskegee Institute Chapel.

On this day in 1917 anti-fascist actress Christiane Grautoff was born in Berlin. Her parents, Otto Grautoff and Erna Heinemann Grautoff, were both art historians and translators. She had two older sisters, Barbara and Uta.

Grautoff begun her stage career as a child actress in 1928, in which she attracted the attention of the legendary Max Reinhardt, who engaged her for a new play by Ferdinand Bruckner. Her performance in this play captivated audiences and critics alike. This led to her being recruited by Erich Kästner for his stage production of Emile and the Detectives. This was also a great success and Grautoff became one of the great attractions of the Berlin stage.

In 1932, aged fifteen, Grautoff, met the writer and political activist, Ernst Toller. In her unpublished autobiography, Grautoff recalled their first meeting: "Ernst Toller's eyes were unendingly sad. His flat was small, his study narrow, the window barred." She would learn that Toller could only write in a small room, preferably with a single barred window which simulated the physical conditions of the prison cell in which he had written his greatest stage successes. Toller went to see Grautoff in her latest play. "From then on, Toller and I saw each other frequently... Ernst and I had a very strange relationship. It was completely platonic... We had long conversations about his life, about my life, his thoughts and my thoughts... Very soon, he began to read to me from his unfinished works."

On 27th February, 1933, the Reichstag parliamentary building caught fire. It was reported at ten o'clock when a Berlin resident telephoned the police and said: "The dome of the Reichstag building is burning in brilliant flames." The Berlin Fire Department arrived minutes later and although the main structure was fireproof, the wood-paneled halls and rooms were already burning.

Adolf Hitler gave orders that all leaders of the German Communist Party (KPD) should "be hanged that very night." Paul von Hindenburg vetoed this decision but did agree that Hitler should take "dictatorial powers". Orders were given for all KPD members of the Reichstag to be arrested. This included Ernst Torgler, the chairman of the KPD. Göring commented that "the record of Communist crimes was already so long and their offence so atrocious that I was in any case resolved to use all the powers at my disposal in order ruthlessly to wipe out this plague".

That night the police attempted to arrest 4,000 people. This included 130 Berlin writers and intellectuals such as Ernst Toller, Bertolt Brecht, Ludwig Renn, Erich Mühsam, Heinrich Mann, Arnold Zweig, George Grosz, John Heartfield, Erwin Piscator, Lion Feuchtwanger, Willi Bredel, Carl von Ossietzky and Kurt Hiller. When they arrived at Toller's flat he was not there. A few days previously he had traveled to Switzerland, where he was to make a series of radio broadcasts. Toller's absence from Germany, probably saved his life as friends such as Mühsam and Ossietzky, who were still in the country, were to die while in custody.

In 1933 Toller moved to London. In January 1934 Toller arranged to meet Christiane Grautoff in Switzerland. He had not seen her for over a year. Now aged seventeen, Toller proposed marriage. A few weeks previously, she had been offered a leading role in a Nazi film eulogizing Horst Wessel, but she rejected it as "she did not care to be a party to a theatre whose theme was race hatred". She agreed to his proposal and after performing in a play in Zurich, under the direction of Gustav Hartung, she moved to London and after their marriage in May 1935 they set up home in Hampstead.

Christine was anxious to pursue her acting career and took lessons in English language and diction. However, it was two years before making her London stage debut as Rachel in Toller's satirical musical comedy, No More Peace. According to Richard Dove: "The relative failure of the play seems to have strengthened his conviction that the theatre was no longer the most suitable medium to convey his message."

Life with Toller was not easy as since leaving Germany he suffered bouts of depression, during which he would spend days lying in a darkened room. These attacks were closely associated with feelings of creative inadequacy, which made him fear that his creative talent had finally deserted him. His changes of mood were abrupt and startling. Fritz Helmut Landshoff remembered that days of self-imposed isolation would suddenly give way, often in the early hours of the morning, to a compulsive need for company and conversation.

In the spring of 1936, Grautoff and Toller and his wife made a six-week car tour of Portugal and Spain, where during their stay in Cintra in mid-April, they met Christopher Isherwood and W. H. Auden. Isherwood later recalled: "Throughout the supper, it was he (Toller) who did most of the talking - and I was glad, like the others, merely to sit and listen; to follow with amused, willing admiration, his every gesture and word. He was all that I had hoped for - more brilliant, more convincing than his books, more daring than his most epic deeds."

In February 1937, Ernst Toller signed a one-year contract to write film-scripts for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, the most powerful and prestigious of all the studios. Toller hoped that he would be given the freedom to write films that dealt with political issues such as the rise of fascism in Europe. "I am settled in a beautiful apartment overlooking the ocean and am trying to spend every free moment, of which there are altogether too few, in the sun at the beach. My work at MGM gives promise of being very agreeable and as I hope successful."

Christiane Grautoff, who had unsuccessfully attempted to make it as a stage actress in New York, joined Toller in Hollywood. Toller first project was a script with Stanley Kaufmann about Lola Montez, an Irish dancer and actress who became famous as a Spanish dancer, courtesan, and mistress of King Ludwig of Bavaria. The subject appealed to Toller because she influenced the king's politics. "Strange as history often is, it was this Lola Montez who was the mouth-piece of freedom at the time of European reaction."

Ernst Toller committed suicide on 22nd May 1939. According to the The New York Times: "Ernst Toller, exiled German writer and lecturer, committed suicide yesterday, hanging himself by a bathrobe cord in his apartment in the Mayflower Hotel, Sixty-first Street and Central Park West. He was 46 years old.... Friends said he had undertaken no new writing but was casting about for further material. They attributed much of his depression to the gloomy view he had to take recently of events in Europe and the threat that he saw in the extension of totalitarianism to the American continent."

Oscar Fischer, a left-wing psychiatrist, was highly critical of Toller's decision to end his life: "Ernest Toller's suicide, which created a sensation not only in the German emigration, cannot be explained merely as a 'personal collapse'. The significance of this case extends much further and the private sides of the 'sensation' recede into the background before the ideological and the political. Toller was a representative of a certain type of the German intelligentsia – and even by his death Toller represented precisely this type just as he did during his life-time. Toller’s fall symbolizes the fall of the democratic-pacifist ideology; his end coincides with the end of the illusions once concentrated in the slogan 'Never again war!' But apart from this symbolical significance, Toller’s death raises at the same time the question of the real state of mind of those circles who consider themselves the spiritual elite of the German (and not only of the German) emigration and the representatives of the German future."

Grautoff was at the time living in Hollywood, rehearsing with other German exiles in an English-language production of Wilhelm Tell, the play written by Friedrich Schiller. The production was to take place at the El Capitan Theatre in Los Angeles. As Grautoff had no understudy she decided that the show must go on and played her role "on an outwardly glittering first night" on 25th May, 1939.

In 1940 she acted in the play by Bruno Frank, entitled, Storm in a Water Glass. Later that year she married the anti-Nazi activist Walter Schönstedt, the author of In Praise of Life (1938). During the Second World War she found employment in a medical laboratory. In 1948 she returned to acting when she appeared in Bravo, a play written by Edna Ferber and George S. Kaufman, at the Lyceum Theater on Broadway. Unfortunately it was not a success.

Christiane Grautoff moved to Mexico City with her daughter, Andrea Valeria. Later she published the children's book, The Stubborn Donkey. Her grand-daughter, Christianne Gout, became a dancer and actress. Christiane Grautoff died on 27th August, 1974.

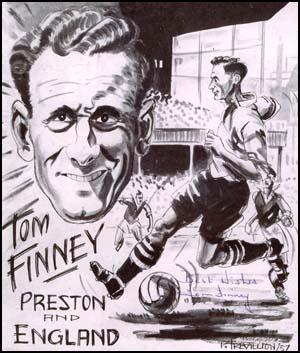

On this day in 1922 footballer Tom Finney is born in Preston. He developed a love of football in his childhood: "The kickabouts we had in the fields and on the streets were daily events, sometimes involving dozens and dozens of kids. There were so many bodies around you had to be flippin' good to get a kick. Once you got hold of the ball, you didn't let it go too easily. That's where I first learned about close control and dribbling."

As a young boy he idolized Alex James: "It was a world of make-believe - were children more imaginative in those days? - and although we only had tin cans and school caps for goalposts, it mattered not a jot. In my mind, this basic field was Deepdale and I was the inside-left, Alex James. I tried to look like him, run like him, juggle the ball and body swerve like him. By being James, I became more confident in my own game. He never knew it, but Alex James played a major part in my development."

Finney was a keen footballer but his small size, at 14 he was only 4ft 9ins tall and weighed under 5 stone, meant that he was not considered for national honours. However, his school, Deepdale Secondary Modern, did reach the final of the Dawson Cup which was played at Deepdale, the ground of Preston North End. Finney scored the winning goal and as he later recalled "I was chaired from the field a hero. Scenes of jubilation surrounded the presentation and we were greeted by hundreds of smiling faces when we came out of the ground."

As a schoolboy, Finney, used to watch Alex James play at Deepdale. "James was the top star of the day, a genius. There wasn't much about him physically, but he had sublime skills and the knack of letting the ball do the work. He wore the baggiest of baggy shorts and his heavily gelled hair was parted down the centre. On the odd occasion when I was able to watch a game at Deepdale, sometimes sneaking under the turnstiles when the chap on duty was distracted, I was in awe of James. Preston were in the Second Division and the general standard of football was not the best, but here was a magic and a mystery about James that mesmerised me."

Finney left school at 14 and joined the family plumbing business. However, Jim Taylor, the chairman of Preston North End, decided to create a youth scheme to identify talented young footballers from Preston. This included funding the under 16 Preston and District League. As Jack Rollin explained in (Soccer at War: 1939-45): "By 1938 the club was already running two teams in local junior circles when the chairman James Taylor decided upon a scheme to fill the gap between school leavers and junior clubs by forming a Juvenile Division of the Preston and District League open to 14-16-year-olds."Rollin points out that by 1940 over 100 youngsters were being trained in groups of eight of the club's senior players voluntarily assisting in evening coaching. Robert Beattie was one of those involved in this coaching. One of the first youngsters to emerge from this youth system was Tom Finney.

On Friday, 1st September, 1939, Adolf Hitler ordered the invasion of Poland. The football that Saturday went ahead as Neville Chamberlain did not declare war on Germany until Sunday, 3rd September. The government immediately imposed a ban on the assembly of crowds and as a result the Football League competition was brought to an end. However, later that month the government gave permission for football clubs to play friendly matches. In the interests of public safety, the number of spectators allowed to see these games was limited to 8,000. These arrangements were later revised, and clubs were allowed gates of 15,000 from tickets purchased on the day of the game through the turnstiles.

The government imposed a fifty mile travelling limit and the Football League divided all the clubs into seven regional areas where games could take place. Preston North End became a member of the North Regional League. Although Finney was only 18 years old, he was considered good enough to play in the first-team. Two other products of the Preston youth system, Andrew McLaren and William Scott, also played in these games.

In 1940 the Football League decided to start a new competition entitled the Football League War Cup. Preston were beaten by Everton in the first round. However, in 1941 Preston beat Bury and Bolton Wanderers in the first two rounds. In the next round nineteen year old Andrew McLaren scored five of the goals in Preston's 12-1 victory over Tranmere. He also scored a hat-trick in the fourth-round tie against Manchester City. Preston reached the final by beating Newcastle United 2-0.

Nineteen year old Tom Finney was picked for the final. The rest of the team that played Arsenal at Wembley on 31st May included: Jack Fairbrother, Frank Gallimore, William Scott, Bill Shankly, Tom Smith, Andrew Beattie, Andrew McLaren, Jimmy Dougal, and Hugh O'Donnell. In front of a 60,000 crowd. Arsenal was awarded a penalty after only three minutes but Leslie Compton hit the foot of the post with the spot kick. Soon afterwards Andrew McLaren scored from a pass from Tom Finney. Preston dominated the rest of the match but Dennis Compton managed to get the equaliser just before the end of full-time.

The replay took place at Ewood Park, the ground of Blackburn Rovers. The first goal was as a result of a move that included Tom Finney and Jimmy Dougal before Robert Beattie put the ball in the net. Frank Gallimore put through his own goal but from the next attack, Beattie scored again. It was the final goal of the game and Preston ended up the winners of the cup. Tom Finney had two great games against England's full-back, Eddie Hapgood, and fully deserved his winners' medal.

In the 1940-1941 season Preston North End needed to win their last game against Liverpool to win the North Regional League title. Andrew McLaren scored all six goals in the 6-1 victory. There is no doubt that during this period Preston was the best football club in England. Other players at the club at the time included Jimmy Dougal, Frank Gallimore, Tom Smith, William Scott, Jack Fairbrother, Bill Shankly, William Jessop, George Mutch, Robert Beattie, George Holdcroft and Hugh O'Donnell. Finney got six goals that season but he was mainly remembered for setting up chances for Dougal, McLaren, Mutch and Beattie.

This great Preston team was broken up by the Second World War. In 1942 Finney was called up to the Royal Armoured Corps. In December 1942 he was sent to fight under General Bernard Montgomery in the Eighth Army in North Africa. "We were posted to a camp next to the pyramids and, with the desert campaign in full swing, thoughts of football disappeared out of my mind. Tom Finney the footballer was now Tom Finney the soldier, involved in all sorts of military manoeuvres, sometimes for 12- and 15-hour streches. The physical demands were punishing in the extreme."

Finney returned to the Preston North End at the beginning of the first season after the war. At 24 he had missed some of his best football years while serving in the British Army. A month later he gained his first international cap playing for England against Northern Ireland. He scored in England's 7-2 victory. The team that day included Raich Carter, Neil Franklin, Wilf Mannion, Tommy Lawton, George Hardwick, Laurie Scott, Frank Swift and Billy Wright.

Finney also scored in his second international game when he netted the only goal in the victory over the Republic of Ireland. Over the next few years Finney was a regular scorer at international level. He added to his total against Holland (November, 1946), France (May, 1947), Portugal (May 1947), Belgium (September 1947), Wales (October, 1947), Scotland (April, 1948), Italy (May, 1948), Wales (November, 1948), Sweden (May, 1949) and Norway (May, 1949). In a game against Portugal in Lisbon on 14th May, 1950, Finney scored 4 goals, in England's 5-3 victory. Finney was later to claim that it was his greatest performance in a England shirt.

Stan Mortensen played with Finney several times during his international career: "Speed is a curious thing in football. You need to be fast, but only over short distances. A man who can beat his team-mates over a hundred yards may be one of the slowest on the field, where speed is all a matter of bursts over a few yards. More important than absolute speed are acceleration and change of pace, and the knack of getting into your stride quickly. Watch Tom Finney... a master of changing pace. He will amble along, rolling the ball like a dancing-master. When the half-back or back is wondering whether to deliver the tackle, he will suddenly lengthen and quicken his stride in the most surprising fashion. There is the trick of slowing down after a full-speed burst, and then speeding up again. If you can do this, you will not find many defenders able to counter the move."

Tommy Lawton played with both Tom Finney and Stanley Matthews. He was once asked to compare them as players: "Tom Finney always looks deadly serious, but his football has an impish character about it. Much of his footwork resembles that of Matthews, but Finney cuts in more than Matthews does, and is also a goal-scorer, whereas Matthews is content to let others do the scoring. Tom can also play equally well on the left wing, and has shown that he is equally skilful at beating an opponent on the inside as well as the outside. Like Matthews, he has a tremendous burst of speed which helps him to float away from his pursuers."

Matt Busby was asked the same question: "Stan Matthews was basically a right-footed player, Tom Finney a left-footed player, though Tom's right was as good as most players' better foot. Matthews gave the ball only when he was good and ready and the move was ripe to be finished off. Finney was more of a team player, Matthews being more of an inspiration to a team than a single part of it. Finney was more inclined to join in moves and build them up with colleagues, by giving and taking back. He would beat a man with a pass or with wonderful individual runs that left the opposition in disarray. And Finney would also finish the whole thing off by scoring, which Stan seldom did. Being naturally left-footed, Tom was absolutely devastating on the right wing. An opponent never seemed to be able to get at him. If you were a problem to him he had two solutions to you. How can anybody say who was the greater ? I think I would choose Matthews for the big occasion - he played as if he was playing the Palladium. I would choose Finney, the lesser showman but still a beautiful sight to see, for the greater impact on his team. For moments of magic - Matthews. For immense versatility - Finney. Coming down to an all-purpose selection about whom I would choose for my side if I could have one or the other I would choose Finney."

Nat Lofthouse, refused to compare the two players in his autobiography, Goals Galore (1954): "To compare Matthews and Finney is not really possible. They are entirely different in style. Whereas Tom Finney takes the ball no matter how it is sent to him, Stan Matthews prefers it direct to his feet. This, quite naturally, limits a centre-forward's distribution. Stanley does not like a centre-forward to veer out on to his beat, but, as you may have noticed, he frequently draws opponents away from the centre-forward and then pushes over a really peachy pass. I am not risking the wrath of millions of his admirers by criticizing Matthews, but I must say that speaking as a centre-forward I prefer the more direct winger. While Stan is beating defenders out on the touch-line, other members of the defence are given valuable time to get back and cover. As another example of how different in style Matthews and Finney are, I must mention their centres and corner-kicks. Finney... hits the ball over hard and all it needs is a deflection to bring disappointment to a goalkeeper. Matthews' crosses, on the other hand, seem to float in the air. Goalkeepers, and other defenders, coming up against this unusual form of centre, are invariably caught in two minds. For the centre-forward, it means a different approach must be made in heading the ball goalwards. With Matthews' centres I have to put my own power behind the ball; in other words, I try to kick the ball with my forehead. For speed over 20 yards, too, Stanley Matthews remains the fastest of all wingers."

It upset Finney that the media constantly reported that he did not got on with Stanley Matthews. Finney commented in his book, My Autobiography (2003): "Imagine how we both felt, continually reading in the newspapers of a so-called feud between us. Time and time again we tried to put the record straight, but it was almost as if the media didn't want to know. Perhaps the truth would have served only to ruin the stories. So let's put a few myths to bed. I have waited a long time for this. Stan and I shared a mutual respect and a close friendship and I categorically refute all rumours suggesting any kind of bad blood or friction."

Matthews confirmed this in his autobiography The Way It Was (2000): "As a player, he (Finney) was happy operating on either wing. He could also drop into midfield to mastermind a game and, when asked, to play as an out-and-out centre-forward. He was a striker of considerable note, as a career total of 187 goals testifies. He took all the corners, the free kicks, throw-ins and penalties and, such was his devotion to Preston, I reckon he would have taken the money on the turnstiles and sold programmes before a match if they'd let him. On the pitch he made ordinary players look great and helped the great players create the magical moments that for years would be sprinkled like gold dust on harsh working-class lives to create cherished memories that would be recalled to grandchildren on the knee. If greatness in football can be defined by the ability of a player to impose his personality on a match and dominate the proceedings throughout, then Tom Finney, for club and country, was indeed a true great. His delayed spurt, lengthened stride, his ability to beat a man then cut in and shoot and, above all, his cunning use of the ball with both feet, posed insurmountable problems for even the best defenders. The sight of one man dictating the fortunes of a team is one of football's greatest and rarest spectacles. To dictate the pace and course of a game, a player has to be blessed with awesome qualities. Those who have accomplished it on a regular basis can be counted on the fingers of one hand - Pele, Maradona, Best, Di Stefano and Tom Finney."

Finney, considered to be the best player playing in the early 1950s, was unable to bring success to Preston North End. He was in the team that was promoted to the First Division in the 1950-51 season. A team-mate, Bill Shankly, said: "Tommy tore Derby County apart in a match shortly after the war. The pitch was a quagmire, but the mud didn't hinder Tommy at all. He trailed the ball past opponents, cut it across the penalty area, won free kicks and penalty kicks and made Derby wish he was a million miles away. It was one of the most remarkable games I can remember...He was a ghost of a player but very strong. He could have played all day in his overcoat."

In 1952 Prince Roberto Lanza di Trabia, the owner of Palermo, tried to sign Finney. "I was 30 and probably at my peak, playing to the top of my form both for North End and for England, when I received what can only be described as an offer of a lifetime. The approach was made by an Italian prince, owner of the Palermo club in Sicily. Prince Roberto Lanza di Trabia, Palermo's millionaire president, was prepared to pay me £130 a month in wages (plus win bonuses of up to £100), provide me with a Mediterranean villa and a brand new Italian sportscar, and pay for the family to fly over as often as they wished. Oh, and there was the little matter of a £10,000 signing-on fee!" However, the club chairman, Nat Buck, a retired businessman who had made his money out of house building, rejected the offer: "Tom, I'm sorry, but the whole thing is out of the question, absolutely out of the question. We are not interested in selling you and that's that. Listen to me, if tha' doesn't play for Preston then tha' doesn't play for anybody."

Finney later explained: "Deep down, I expected no other reaction, but I was still more than a little put out by the way he just dismissed it. However, I accepted the decision without too much fuss and tried to forget about the whole affair. That was easier said than done. There was a genuine appeal about the prospect of trying my luck abroad, not to mention the money and the standard of living, and I couldn't help but think I might regret this missed opportunity for the rest of my life.... Nat Buck tried to prevent any further inquiry from Palermo - or anywhere else for that matter - by placing £50,000 valuation on my head. That said everything and in some ways it was very flattering. The world record transfer fee of the day was still some way short of £20,000 so it proved just how much Preston valued me."

The club also finished second to Arsenal in 1952-53 and reached the 1954 FA Cup Final. However, he did not have a good game and West Bromwich Albion won 3-2. Finney later wrote: "It turned out to be an unmitigated disaster and a complete embarrassment. The day was a collective and personal disaster.... Unlike most of my team-mates, I had experienced the feel of Wembley before, but if they looked to me for help and guidance they were wasting their time. In the dressing room and walking out from the tunnel I was fine; it was just when the match started that my problems took hold and didn't let go... I had a stinker."

In August 1956 Cliff Britton became manager of Preston North End. One of his first decisions was to play the Finney as centre-forward. Finney scored 23 goals the 1956-57 season and Preston finished third in the First Division. The following season they finished runners-up to Wolverhampton Wanderers.

As Dean Hayes pointed out in Who's Who of Preston North End (2006): "One thing on which all who played with or against Tom Finney agree is that, in addition to all his skill, he never lacked courage. In his time he took a large amount of punishment. this is reflected in the fact that he missed 115 matches - most of them in ones, twos and threes - through injury of one kind of another." As his teammate Bill Shankly once said: "Tom Finney would go through a mountain."

Tom Finney retired in 1959. During his time at Preston North End he scored 210 goals in 473 league and cup games. It is claimed that during that period he earned only £15,000 from football. He explained in My Autobiography (2003): "At my peak, in a structure governed by the maximum wage, my income from a playing year with Preston North End struggled to reach £1,200. When I first signed as a professional it was for shillings - ten bob a match to be precise. That's 50p. So when you read of players now being paid up to £100,000 a week for doing the same job, you might think I would be envious but you would be wrong. I would never criticise players for the amounts they are paid. It is not their fault and I say good luck to them, go out there and grasp the opportunity."

Tom Finney, died on 14th February 2014.

On this day in 1933 President Franklin D. Roosevelt orders the establishment of the Civilian Conservation Corps. After he was elected President Roosevelt initially opposed massive public works spending. However, by the spring of 1933, the needs of more than fifteen million unemployed had overwhelmed the resources of local governments. In some areas, as many as 90 per cent of the people were on relief and it was clear something needed to be done. His close advisors and colleagues, Harry Hopkins, Rexford Tugwell, Robert LaFollette Jr. Robert Wagner, Fiorello LaGuardia, George Norris and Edward Costigan eventually won him over.

Frances Perkins explained in her book, The Roosevelt I Knew (1946): In one of my conversations with the President in March 1933, he brought up the idea that became the Civilian Conservation Corps. Roosevelt loved trees and hated to see them cut and not replaced. It was natural for him to wish to put large numbers of the unemployed to repairing such devastation. His enthusiasm for this project, which was really all his own, led him to some exaggeration of what could be accomplished. He saw it big. He thought any man or boy would rejoice to leave the city and work in the woods. It was characteristic of him that he conceived the project, boldly rushed it through, and happily left it to others to worry about the details."

On 21st March, 1933, sent an unemployment relief message to Congress. It took only eight days to create the Civilian Conservation Corps. It authorized half a billion dollars in direct federal grants to the states for relief. The CCC was a program designed to tackle the problem of unemployed young men aged between 18 and 25 years old. By September, 1935, over five hundred thousand young men lived in CCC camps.

The CCC camps were set up all over the United States. Blackie Gold told Studs Terkel: "I was at CCC's for six months, I came home for fifteen days, looked around for work, and I couldn't make $30 a month, so I enlisted back in the CCC's and went to Michigan. I spent another six months there planting trees and building forests. And came out. But still no money to be made. So back in the CCC's again. From there I went to Boise, Idaho, and was attached to the forest rangers. Spent four and a half hours fighting forest fires."

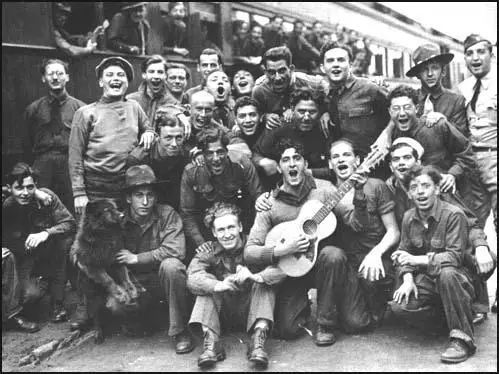

The organisation was based on the armed forces with officers in charge of the men. Over 25,000 men were First World War veterans. The pay was $30 dollars a month with $22 dollars of it being sent home to dependents. The men planted three billion trees, built public parks, drained swamps to fight malaria, built a million miles of roads and forest trails, restocked rivers with nearly a billion fish, worked on flood control projects and a range of other work that helped to conserve the environment. Between 1933 and 1941 over 3,000,000 men served in the CCC.

On this day in 1944 Special Operations Executive (SOE) agent Lilian Rolfe is flown to France. Lilian Rolfe, the daughter of George Rolfe, a chartered accountant, was born in Paris, France, on 26th April, 1914. The family moved to Brazil in 1930.

On the outbreak of the Second World War Lilian was working for the British Embassy in Rio de Janeiro. Lilian was asked to monitor German shipping movements in the harbour and this got her involved in espionage work.

In 1943 Lilian moved to England and joined the Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) as a wireless operator. Lilian's ability to speak French fluently brought her to the attention of the Special Operations Executive (SOE). After being interviewed in November 1943, she agreed to become a British special agent.

Given the code name "Nadine", Lilian was flown to France on 5th April 1944 where she joined the Historian network led by George Wilkinson. Over the next three months she sent 67 messages to the SOE in London.

Wilkinson was captured near Orleans at the end of June. The following month, on 31st July, Lilian was arrested while staying in a house in Nangis. After being interrogated by the Gestapo she was sent to Fresnes Prison. In August 1944 she was deported to Nazi Germany and was executed at the Ravensbruck concentration camp in January 1945.

On this day in 1950 General Douglas MacArthur is relieved of his command in Korea. In 1945 MacArthur was named Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) and he received the formal surrender and President Harry S. Truman appointed him as head of the Allied occupation of Japan. He was given responsibility of organizing the war crimes tribunal in Japan and was criticized for his treatment of Tomoyuki Yamashita, who was executed 23rd February, 1946. However he was praised for successfully encouraging the creation of democratic institutions, religious freedom, civil liberties, land reform, emancipation of women and the formation of trade unions.

On the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, MacArthur was appointed commander of the United Nations forces. The surprise character of the attack enabled the North Koreans to occupy all the South, except for the area around the port of Pusan. On 15th September, 1950, MacArthur landed American and South Korean marines at Inchon, 200 miles behind the North Korean lines. The following day he launched a counterattack on the North Koreans. When they retreated, MacArthur's forces carried the war northwards, reaching the Yalu River, the frontier between Korea and China on 24th October, 1950.

Harry S. Truman and Dean Acheson, the Secretary of State, told MacArthur to limit the war to Korea. MacArthur disagreed, favoring an attack on Chinese forces. Unwilling to accept the views of Truman and Acheson, MacArthur began to make inflammatory statements indicating his disagreements with the United States government.

MacArthur gained support from right-wing members of the Senate such as Joe McCarthy who led the attack on Truman's administration: "With half a million Communists in Korea killing American men, Acheson says, 'Now let's be calm, let's do nothing'. It is like advising a man whose family is being killed not to take hasty action for fear he might alienate the affection of the murders."

In April 1951, Harry S. Truman removed MacArthur from his command of the United Nations forces in Korea. McCarthy now called for Truman to be impeached and suggested that the president was drunk when he made the decision to fire MacArthur: "Truman is surrounded by the Jessups, the Achesons, the old Hiss crowd. Most of the tragic things are done at 1.30 and 2 o'clock in the morning when they've had time to get the President cheerful."

On his arrival back in the United States MacArthur led a campaign against Harry S. Truman and his Democratic Party administration. Soon after Dwight Eisenhower was elected president in 1952 he consulted with MacArthur about the Korean War. MacArthur's advice was the "atomic bombing of enemy military concentrations and installations in North Korea" and an attack on China. He rejected the advice and MacArthur played no role in Eisenhower's new Republican administration.

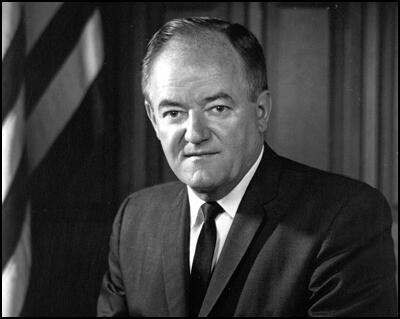

On this day in 1968 Hubert Humphrey makes a speech on the death of Martin Luther King. "Last night, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., died a martyr's death. His death snatched from American life something rare and precious, the living reminder that one man can make a difference - that one man, by the force of his character, the depth of his convictions, and the eloquence of his voice - can alter the course of history. What a testimonial to individualism, what a testimonial to dignity and to human purpose - for Martin Luther King had the courage to challenge the intolerance, the injustice, inadequacies and inequities of the society in which he lived - a nation that he loved - a nation of which he was a citizen - and a nation for which he prayed and worked."

On this day in 1884 Arthur Harris died. Arthur Harris, the son of George Steele Travers Harris and his wife, Caroline Harris, was born in Cheltenham, on . His father was an engineer and architect in the Indian Civil Service. He was educated at Gore Court in Sittingbourne and Allhallows in Honiton, while his parents were in India. At the age of seventeen, against the wishes of his father, who wanted him to join the army, he went out to Rhodesia, where he tried his hand at goldmining, coach-driving, and farming.

When the First World War broke out he joined the 1st Rhodesia Regiment and fought in the successful campaign to capture German South West Africa from the German Army. Harris returned to England in 1915 and with the help of an uncle joined the Royal Flying Corps. The following year he qualified as a fighter pilot and joined the 44 Squadron in France. Harris also helped organize the defence against the Zeppelin Air Raids in 1916 before taking command of the 44 Squadron and training it for night fighting.

According to his biographer, Richard Overy: "Harris married, on 30 August 1916, Barbara Daisy Kyrle, the daughter of Lieutenant-Colonel Ernle William Kyrle Money, of the 85th King's Shropshire light infantry, with whom he had a son and two daughters... Posted to 70 squadron in France, he was invalided home after a crash, but he returned in May 1917 for fighter work with 45 squadron. Here he displayed many of his later qualities as a commander. He proved to be a cool and effective pilot and was attributed with five aerial victories. He constantly searched for ways to improve the tactical or technical performance of his squadron. He was also a strict officer, with high standards that he imposed on those around him."

In 1919 Harris was given the rank of squadron leader of the recently created Royal Air Force (RAF). Over the next few years he served in India, Iraq and Iran. He led the 58 Squadron (1925-27) before serving on the air staff in the Middle East (1930-32). During this period the RAF used terror bombing, including gas attacks and delayed action bombs, on the Iraqi tribes rebelling against British rule. One RAF officer, Air Commodore Lional Charlton, resigned in 1924 after visiting a hospital that contained limbless civilian victims of these air raids. However, Harris remarked "the only thing the Arab understands is the heavy hand."

During 1928–9 Harris attended the Army Staff College at Camberley, where he was taught by, among others, Bernard Montgomery. He refused the offer to stay on as an instructor at the college, and was posted for two years to serve on the air staff in Cairo. In 1932 Harris was appointed commander of the 210 Flying Boat Squadron. Promoted to group captain in 1933 Harris was appointed deputy director of plans in the Air Ministry (1934-37). In this post he argued for the production of bombers that could reach the Soviet Union. Harris believed that communism was the main threat to Britain and was considered to be one of the earliest "cold war warriors". However, he believed that eventually Britain would go to war with Nazi Germany and correctly forecasted the starting date as 1939.

By the outbreak of the Second World War Harris had reached the rank of air vice marshal and spent the early months of the war in the United States purchasing aircraft for the war effort. In November, 1940, Harris was appointed to serve under Charles Portal, the head of Bomber Command. In May 1941 Portal sent Harris back to the United States as head of the RAF delegation to try to speed up the supply of aircraft and engines from American industry, many of which had been on order since 1939. Harris found his relationship with the Americans difficult. He told friends that he disliked having to deal with "a people so arrogant" that they simply refused to listen to technical advice from the British. Harris also complained that they "are not going to fight" unless pushed into war.

In February 1942, following the sacking of Air Chief Marshal Richard Pierse the previous month, Harris was recalled from Washington to be appointed commander-in-chief of Bomber Command. Richard Overy has argued: "The choice of Harris was recognition of his long experience, enormous capacity for work, organizational capabilities, and clear-mindedness. It also came despite his less flattering reputation as a man who spoke his mind bluntly, who would suffer fools not at all, and who had often in the past allowed his candour to get the better of his sense of responsibility. Though many in the Air Ministry regarded him as gruff and unapproachable, he was also able to inspire intense loyalty in those who served with him. The force of fewer than 400 operational bombers that Harris inherited had only a handful of the new four-engined aircraft, and was capable of only the most modest and inaccurate attacks on areas of western Germany."

Arthur Harris claimed that his brief was "to focus attacks on the morale of the enemy civil population, and in particular, of the industrial workers". According to Richard K. Morris: "During March and April he had begun to experiment with attacks which concentrated bombers in time and space, to engulf radar-controlled flak and fighters, and overwhelm a city's fire-services. The force inherited by Harris was nevertheless too small to do this on any scale, and his efforts to increase it were being sapped both by losses and what he called the robbery of trained crews by other commands. To make his case, Harris decided to gamble Bomber Command's reserves in an attack of unprecedented weight: a thousand aircraft against a single objective."

As Harris later pointed out: "The organization of such a force - about twice as great as any the Luftwaffe ever sent against this country - was no mean task in 1942. As the number of first-line aircraft in squadrons was quite inadequate, the training organization.... We made our preparations for the thousand bomber attack during May." It was given the code word "Millenium". More than a third of his force was composed of instructors and trainees. Heavy losses among them would have a "paralysing effect" on Bomber Command's future.

On 20th May, 1942, Harris notified his group commanders of the plan and all leave was cancelled. Harris decided that the target should be Cologne. "The organisation of the force involved a tremendous amount of work throughout the Command. The training units put up 366 aircraft. No. 3 Group, with its conversion units put up about 250 aircraft, which was at that time regarded as a strong force in itself. Apart from four aircraft of Flying Training Command, the whole force of 1047 aircraft was provided by Bomber Command.... Nearly 900 aircraft attacked out of the total of 1047, and within an hour and a half dropped 1455 tons of bombs, two thirds of the whole load being incendiaries."

Leonard Cheshire, one of the pilots involved in the attack, explained in his book, Bomber Pilot (1943): "I glued my eyes on the fire and watched it grow slowly larger. Of ack-ack there was not much, but the sky was filled with fighters.... Already, only twenty-three minutes after the attack had started, Cologne was ablaze from end to end, and the main force of the attack was still to come. I looked at the other bombers, I looked at the row of selector switches in the bomb compartment, and I felt, perhaps, a slight chill in my heart. But the chill did not stay long: I saw other visions, visions of rape and murder and torture. And somewhere in the carpet of greyish-mauve was a tall, blue-eyed figure waiting behind barbed-wire' walls for someone to bring him home. No, the chill did not last long.... I felt a curious happiness inside my heart. For the first time in history the emphasis of night bombing had passed out of the hands of the pilots and into the hands of the organizers, and the organizers had proved their worth. In spite of the ridicule of some of their critics, they have proved their worth. They have proved, too, beyond any shadow of doubt that given the time the bomber can win the war. Not only have they proved it, they have written the proof on every face that saw Cologne."

Harris explained in Bomber Command (1947): "The casualty rate was 3.3 per cent, with 39 aircraft missing, and, in spite of the fact that a large part of the force consisted of semi-trained crews and that many more fighters were airborne than usual, this was considerably less than the average 4.6 per cent for operations in similar weather during the previous twelve months. The medium bomber had a casualty rate of 4.5 per cent, which was remarkable, but it was still more remarkable that we lost scarcely any of the 300 heavy bombers that took part in this operation; the casualty rate for the heavies was only 1.9 per cent. These had attacked after the medium bombers, when the defences had been to some extent beaten down, and in greater concentration than was possible for the new crews in the medium bombers. The figures proved conclusively that the enemy's fighters and flak had been effectively saturated; an analysis of all reports on the attack showed that the enemy's radar location devices had been able to pick up single aircraft and follow them throughout the attack, but that the guns had been unable to engage more than a small proportion of the large concentration of aircraft."

Under his leadership the policy of area bombing (known in Germany as terror bombing) was developed. Harris argued that the main objectives of night-time blanket bombing of urban areas was to undermine the morale of the civilian population and attacks were launched on Hamburg, Berlin, Cologne, Dresden and other German cities. This air campaign killed an estimated 600,000 civilians and destroyed or seriously damaged some six million homes. It was a highly dangerous strategy and during the war Bomber Command had 57,143 men killed.

In March, 1945, Winston Churchill gave instructions to Harris to bring an end to area bombing. As he explained: "It seems to me that the moment has come when the question of bombing of German cities simply for the sake of increasing the terror, should be reviewed. Otherwise we shall come into control of an utterly ruined land." As Richard Overy pointed out: "Harris reacted angrily to the charge by arguing that he had 'never gone in for terror bombing’ and that city bombing was still justified in order to speed up surrender and avoid further allied casualties. He had already crossed swords with the chief of air staff, Portal, in December 1944, over his preference for city attacks over attacks on specific target systems. The new arguments angered and puzzled him."

Arthur Harris became a marshal of the Royal Air Force in 1946 and soon afterwards retired from active duty. He published his war memoirs, Bomber Command, in 1947. Upset by criticisms of his bombing strategy during the Second World War he went to live in South Africa where he ran a shipping line, the South African Marine Corporation.

When Winston Churchill became prime minister again in 1951 Harris was asked if he wanted a peerage, but he refused. In January 1953 he accepted a baronetcy instead. In the 1960s public opinion turned against Harris and he was viewed by many as a "war criminal" because of his area bombing strategy. When it was decided to erect a statue to Harris to stand next to Hugh Dowding outside the RAF church of St Clement Danes in the Strand in London, there were widespread objections.

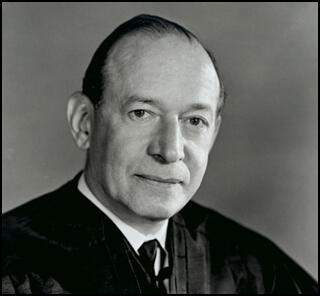

On this day in 1982 Supreme Court judge Abe Fortas died. Abe Fortas was born in Memphis, Tennessee on 19th June 19, 1910. His parents were Russian Jews who had arrived in the United States at the beginning of the 20th century.

Fortas studied at Yale Law School. He was also the editor-in-chief of the Yale Law Journal. In 1933 he moved to Washington where he worked for the Agriculture Department. During the Second World War Fortas worked in the Department of the Interior.

After the war Fortas joined with Thurman Arnold and Paul Porter to establish the firm of Arnold, Fortas and Porter. It eventually became one of the most important law firms in Washington.

Lyndon B. Johnson ran for Senator from Texas in 1948. His main opponent in the Democratic primary (then a one party state, contested elections occurred in primaries, not the general election) was Coke Stevenson. Johnson won by 87 votes but Stevenson accused him of ballot-rigging. Stevenson obtained an injunction preventing Johnson's name from appearing on the ballot for the general election. Fortas represented Johnson in this long-drawn out dispute. The case was investigated by J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI. Johnson was eventually cleared by Hoover of corruption and was allowed to take his seat in the Senate.

Fortas and Johnson now became close friends. Fortas' legal advice became important during the investigation into the activities of Billie Sol Estes and Bobby Baker. On 22nd November, 1963, Don B. Reynolds appeared before a secret session of the Senate Rules Committee. Reynolds told B. Everett Jordan and his committee that Johnson had demanded that he provided kickbacks in return for him agreeing to a life insurance policy arranged by him in 1957. This included a $585 Magnavox stereo. Reynolds also had to pay for $1,200 worth of advertising on KTBC, Johnson's television station in Austin. Reynolds had paperwork for this transaction including a delivery note that indicated the stereo had been sent to the home of Johnson.

Reynolds also told of seeing a suitcase full of money which Bobby Baker described as a "$100,000 payoff to Johnson for his role in securing the Fort Worth TFX contract". His testimony came to an end when news arrived that President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated.

As soon as Lyndon B. Johnson became president he contacted B. Everett Jordan to see if there was any chance of stopping this information being published. Jordan replied that he would do what he could but warned Johnson that some members of the committee wanted Reynold's testimony to be released to the public. On 6th December, 1963, Jordan spoke to Johnson on the telephone and said he was doing what he could to suppress the story because " it might spread (to) a place where we don't want it spread."

Fortas, who represented both Lyndon B. Johnson and Bobby Baker, worked behind the scenes in an effort to keep this information from the public. Johnson also arranged for a smear campaign to be organized against Don B. Reynolds. To help him do this J. Edgar Hoover passed to Johnson the FBI file on Reynolds.

On 17th January, 1964, the Senate Rules Committee voted to release to the public Reynolds' secret testimony. Johnson responded by leaking information from Reynolds' FBI file to Drew Pearson and Jack Anderson. On 5th February, 1964, the Washington Post reported that Reynolds had lied about his academic success at West Point. The article also claimed that Reynolds had been a supporter of Joseph McCarthy and had accused business rivals of being secret members of the American Communist Party. It was also revealed that Reynolds had made anti-Semitic remarks while in Berlin in 1953.

A few weeks later the New York Times reported that Lyndon B. Johnson had used information from secret government documents to smear Don B. Reynolds. It also reported that Johnson's officials had been applying pressure on the editors of newspapers not to print information that had been disclosed by Reynolds in front of the Senate Rules Committee.

In 1965 Johnson nominated Fortas as a member of the Supreme Court. During his time on the Court, Fortas continued to advise Johnson on political and legal matters. In June 1968, Earl Warren retired as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Johnson had no hesitation in appointing Fortas as his replacement. Johnson also appointed another friend from Texas, Homer Thornberry, to replace Fortas. The Senate had doubts about the wisdom of Fortas becoming Chief Justice. It was later discovered that Fortas had lied when he appeared before the Senate Judiciary Committee. In October, Fortas asked for his nomination to be withdrawn.

It was also revealed that a convicted financier named Louis Wolfson had agreed to pay Fortas $20,000 per year for the remainder of his life. This arrangement was condemned as ethically improper and Fortas was forced to resign from the Supreme Court in May 1969.

Abe Fortas was unsuccessful in his attempt to rejoin Arnold, Fortas and Porter, the law firm he had helped create. In 1970 he started another law firm.