On this day on 4th May

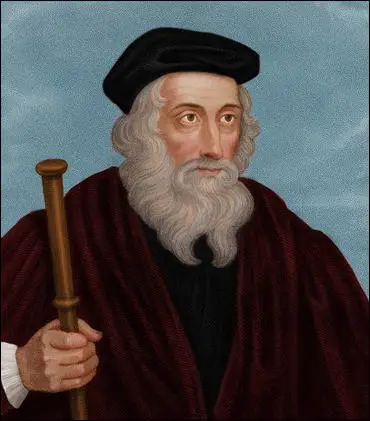

On this day in 1415 John Wycliffe is condemned as a heretic at the Council of Constance. The Council was a 15th-century ecumenical council recognized by the Catholic Church, held from 1414 to 1418 in the Bishopric of Constance in present-day Germany. The council ended the Western Schism by deposing or accepting the resignation of the remaining papal claimants and by electing Pope Martin V.

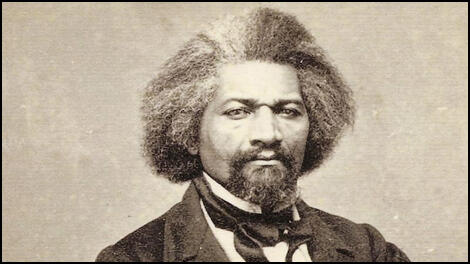

On this day in 1850 Salmon P. Chase writes to Frederick Douglass. "I should be glad to learn your views as to the probable destiny of the Afro-American race in this country. My own opinion has been that the black and white races, adapted to different latitudes and countries by the influences of climate and other circumstances, operating through many generations, would never have been brought together in one community, except under the constraint of force, such as that of slavery. While, therefore, I have been utterly opposed to any discrimination in legislation against our coloured population, and have uniformly maintained the equal rights of all men to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. I have always looked forward to the separation of the races."

On this day in 1850 Leonard Horner, Inspector of Factories Report. "On the 4th May, Mr. Jones and I visited the factory of Christopher Bracewell & Brothers at Earby. It stands apart from the village, in an open field, and as we came near, one of the brothers was seen running with considerable speed from the house to the mill. This looked very suspicious, but we did not discover anything wrong. A few days afterwards I received an anonymous letter stating that when Mr. Bracewell saw the factory inspector he went to the mill, and got those under age into the privies. He also said that the children worked from 13 to 14 hours a day. In a few days, Mr. Jones went again to the mill, taking the superintendent of police at Colne along with him. After having made his first examination, he directed the constable to search the privies, and there were found in them thirteen children. All of them were found to be illegally employed in the mill."

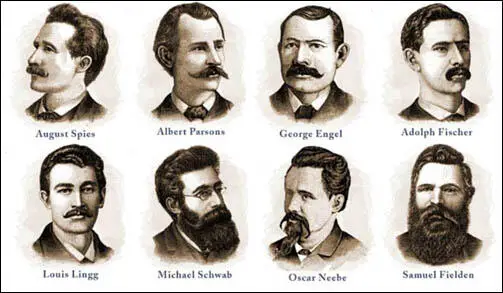

On this day in 1886 Haymarket bombing takes place. On 1st May, 1886 a strike was began throughout the United States in support a eight-hour day. Over the next few days over 340,000 men and women withdrew their labor. Over a quarter of these strikers were from Chicago and the employers were so shocked by this show of unity that 45,000 workers in the city were immediately granted a shorter workday.

The campaign for the eight-hour day was organised by the International Working Men's Association (the First International). On 3rd May, the IWPA in Chicago held a rally outside the McCormick Harvester Works, where 1,400 workers were on strike. They were joined by 6,000 lumber-shovers, who had also withdrawn their labour. While August Spies, one of the leaders of the IWPA was making a speech, the police arrived and opened-fire on the crowd, killing four of the workers.

The following day August Spies, who was editor of the Arbeiter-Zeitung, published a leaflet in English and German entitled: Revenge! Workingmen to Arms!. It included the passage: "They killed the poor wretches because they, like you, had the courage to disobey the supreme will of your bosses. They killed them to show you 'Free American Citizens' that you must be satisfied with whatever your bosses condescend to allow you, or you will get killed. If you are men, if you are the sons of your grand sires, who have shed their blood to free you, then you will rise in your might, Hercules, and destroy the hideous monster that seeks to destroy you. To arms we call you, to arms." Spies also published a second leaflet calling for a mass protest at Haymarket Square that evening.

On 4th May, over 3,000 people turned up at the Haymarket meeting. Speeches were made by August Spies, Albert Parsons and Samuel Fielden. At 10 a.m. Captain John Bonfield and 180 policemen arrived on the scene. Bonfield was telling the crowd to "disperse immediately and peaceably" when someone threw a bomb into the police ranks from one of the alleys that led into the square. It exploded killing eight men and wounding sixty-seven others. The police then immediately attacked the crowd. A number of people were killed (the exact number was never disclosed) and over 200 were badly injured.

Several people identified Rudolph Schnaubelt as the man who threw the bomb. He was arrested but was later released without charge. It was later claimed that Schnaubelt was an agent provocateur in the pay of the authorities. After the release of Schnaubelt, the police arrested Samuel Fielden, an Englishman, and six German immigrants, August Spies, Adolph Fisher, Louis Lingg, George Engel, Oscar Neebe, and Michael Schwab. The police also sought Albert Parsons, the leader of the International Working Peoples Association in Chicago, but he went into hiding and was able to avoid capture. However, on the morning of the trial, Parsons arrived in court to standby his comrades.

There were plenty of witnesses who were able to prove that none of the eight men threw the bomb. The authorities therefore decided to charge them with conspiracy to commit murder. The prosecution case was that these men had made speeches and written articles that had encouraged the unnamed man at the Haymarket to throw the bomb at the police.

The jury was chosen by a special bailiff instead of being selected at random. One of those picked was a relative of one of the police victims. Julius Grinnell, the State's Attorney, told the jury: "Convict these men make examples of them, hang them, and you save our institutions."

At the trial it emerged that Andrew Johnson, a detective from the Pinkerton Agency, had infiltrated the group and had been collecting evidence about the men. Johnson claimed that at anarchist meetings these men had talked about using violence. Reporters who had also attended International Working Peoples Association meetings also testified that the defendants had talked about using force to "overthrow the system".

During the trial the judge allowed the jury to read speeches and articles by the defendants where they had argued in favour of using violence to obtain political change. The judge then told the jury that if they believed, from the evidence, that these speeches and articles contributed toward the throwing of the bomb, they were justified in finding the defendants guilty.

All the men were found guilty: Albert Parsons, August Spies, Adolph Fischer, Louis Lingg and George Engel were given the death penalty. Whereas Oscar Neebe, Samuel Fielden and Michael Schwab were sentenced to life imprisonment. On 10th November, 1887, Lingg committed suicide by exploding a dynamite cap in his mouth. The following day Parsons, Spies, Fisher and Engel mounted the gallows. As the noose was placed around his neck, Spies shouted out: "There will be a time when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strangle today."

Many people believed that the men had not been given a fair trial and in 1893, John Peter Altgeld, the new governor of Illinois, pardoned Oscar Neebe, Samuel Fielden and Michael Schwab. Altgeld argued: "It is further shown here that much of the evidence given at the trial was a pure fabrication; that some of the prominent police officials, in their zeal, not only terrorized ignorant men by throwing them into prison and threatening them with torture if they refused to swear to anything desired but that they offered money and employment to those who would consent to do this. Further, that they deliberately planned to have fictitious conspiracies formed in order that they might get the glory of discovering them."

David Roediger has argued: "Haymarket's bomb echoed long and deep. The explosion and ensuing repression decimated the anarchist labor movement, though the martyred defendants became heroes to many and inspired countless individual conversions to anarchism and to socialism... The pardons ruined Altgeld's promising political career. The tactic of the mass strike was far less appealing to pragmatic U.S. labor leaders after Haymarket, and the idea of self-defense by labor never again received so broad a hearing on the national scale."

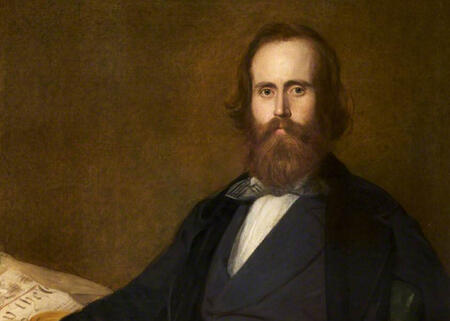

On this day in 1870 the second reading of the Suffrage Bill, drafted by Richard Pankhurst, giving votes to women is passed. In November 1867, Jacob Bright was elected to represent Manchester in the House of Commons. Bright now joined forces with John Stuart Mill, another supporter of women's suffrage. In a debate on the 1867 Reform Act, Mill proposed that women should be granted the same rights as men. "We talk of political revolutions, but we do not sufficiently attend to the fact that there has taken place around us a silent domestic revolution: women and men are, for the first time in history, really each other's companions... when men and women are really companions, if women are frivolous men will be frivolous... the two sexes must rise or sink together."

Mill lost his Commons seat in 1868, and Bright became leader of the suffragists in parliament, and took charge of the Women's Disabilities Removals Bill. In 1870 Bright and Sir Charles Wentworth Dilke introduced what was the first women's suffrage bill. In one speech he argued: "I know of no reason for the electoral disabilities of women. I know some reasons, which if there are to be electoral disabilities, would lead me to begin elsewhere than with women. Women are less criminal than men: they are more temperate than men the distinction is not small, it is broad and conspicuous; women are less vicious in their habits than men; they are more thrifty, more provident: they give more to the family, and take less to themselves."

In November 1867, Jacob Bright was elected to represent Manchester in the House of Commons. Bright now joined forces with John Stuart Mill, another supporter of women's suffrage. In a debate on the 1867 Reform Act, Mill proposed that women should be granted the same rights as men. "We talk of political revolutions, but we do not sufficiently attend to the fact that there has taken place around us a silent domestic revolution: women and men are, for the first time in history, really each other's companions... when men and women are really companions, if women are frivolous men will be frivolous... the two sexes must rise or sink together."

Mill lost his Commons seat in 1868, and Bright became leader of the suffragists in parliament, and took charge of the Women's Disabilities Removals Bill. In 1870 Bright and Sir Charles Wentworth Dilke introduced what was the first women's suffrage bill. After a serious and dignified debate on 4th May its second reading was, carried by 124 to 91.

Bright argued: "I know of no reason for the electoral disabilities of women. I know some reasons, which if there are to be electoral disabilities, would lead me to begin elsewhere than with women. Women are less criminal than men: they are more temperate than men the distinction is not small, it is broad and conspicuous; women are less vicious in their habits than men; they are more thrifty, more provident: they give more to the family, and take less to themselves." (9)

During the committee stage William Gladstone announced his determined opposition, and the majority melted away. "It would be a very great mistake to carry this Bill into law," he said, and though he gave no reasons the whole tone of the House changed forthwith, and when the second vote was taken the hostile majority was 106. As Ray Strachey pointed out: "So ended the early hopes of parliamentary success. The women realised at last the feebleness of the individual support they had won, and the extent of the opposition they had to overcome."

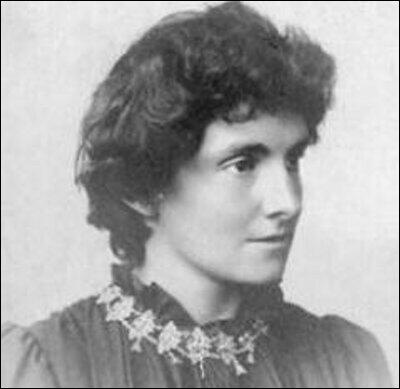

On this day in 1924 author and political activist, Edith Nesbit died from lung cancer at her home in St Mary's Bay in Romney Marsh,

Edith Nesbit, the daughter of John Collis Nesbit, a schoolmaster, was born on 19th August, 1858. Nesbit ran successful schools in Bradford, Manchester and London but died when Edith was only six years old. Despite money problems, Edith's mother managed to educate her daughter in boarding schools in Brighton and France. She later recalled: "When I was a little child I used to pray fervently, tearfully, that when I should be grown up I might never forget what I thought and felt and suffered then".

At the age of nineteen, Edith Nesbit met Hubert Bland, a young writer with radical political opinions. In 1879 discovered she was pregnant and the baby was born two months after they were married on 22nd April, 1880. According to her biographer, Julia Briggs: "Bland continued to spend half of each week with his widowed mother and her paid companion, Maggie Doran, who also had a son by him, though Edith did not realize this until later that summer when Bland fell ill with smallpox. With characteristic optimism, she forgave him, befriended Maggie, and set about supporting the household by writing sentimental poems and short stories, and by hand-painting greetings cards."

Edith and Hubert were both socialists and on 24th October 1883 they decided with their Quaker friend Edward Pease, to form debating group. They were also joined by Havelock Ellis and Frank Podmore and in January 1884 they decided to call themselves the Fabian Society. Bland chaired the first meeting and was elected treasurer. Nesbit and her husband became joint editors of the society's journal, Today. Soon afterwards other socialists in London began attending meetings. This included Eleanor Marx, Annie Besant, Olive Schreiner, Clementina Black, Sidney Webb and Beatrice Webb.

In April 1884 Edith wrote to her friend, Ada Breakell: "I should like to try and tell you a little about the Fabian Society - it's aim is to improve the social system - or rather to spread its news as to the possible improvements of the social system. There are about thirty members - some of whom are working men. We meet once a fortnight - and then someone reads a paper and we all talk about it. We are now going to issue a pamphlet. I am on the Pamphlet Committee. Now can you fancy me on a committee? I really surprise myself sometimes."

George Bernard Shaw joined the Fabian Society in August 1884. Edith wrote: "The Fabian Society is getting rather large now and includes some very nice people, of whom Mr. Stapelton is the nicest and a certain George Bernard Shaw the most interesting. G.B.S. has a fund of dry Irish humour that is simply irresistible. He is a clever writer and speaker - is the grossest flatterer I ever met, is horribly untrustworthy as he repeats everything he hears, and does not always stick to the truth, and is very plain like a long corpse with dead white face - sandy sleek hair, and a loathsome small straggly beard, and yet is one of the most fascinating men I ever met."

In 1885 Edith Nesbit and Hubert Bland also joined the Social Democratic Federation. Other members included Tom Mann, John Burns, Eleanor Marx, William Morris, George Lansbury, Edward Aveling, H. H. Champion, John Scurr, Guy Aldred, Dora Montefiore, Frank Harris, Clara Codd, John Spargo and Ben Tillet. However, they did not stay long as they found the views of its leader, H. H. Hyndman, too revolutionary.

Edith Nesbit wrote two novels, The Prophet's Mantle (1885) and Something Wrong (1886), about the early days of the socialist movement, under the pen-name Fabian Bland. In 1885 Edith had a second child and named him Fabian. In February 1886, Edith gave birth to a stillborn child, and her friend Alice Hoatson, the assistant secretary of the Fabian Society, came to look after her. Alice stayed as their housekeeper in a ménage à trois, and the following year, Alice gave birth to Hubert's baby, Rosamund. Edith accepted the situation and brought up Rosamund as her own child.

Hubert's promiscious behaviour encouraged her to have relationships with other men. The poet Richard Le Gallienne was one of those who found her very attractive and was charmed by her "tall lithe boyish-girl figure, admirably set off by her plain Socialist gown, with her short hair, and her large vivid eyes". Another admirer commented on "the sheer magnificence of her appearance... with a long full throat, and dark luxuriant hair, smoothly parted." George Bernard Shaw found her very attractive and met her two or three times a week at local cafes. However, in May 1887 he reported that "she went away after an unpleasant scene caused by my telling her I wished her to go as I was afraid that a visit to me (at his home) would compromise her."

Another close friend was Oswald Barron, a young journalist. Claire Tomalin points out: "He was one of a band of her courtiers, recent Oxford graduates who joined the Fabian Society and were fascinated by the Blands, and notably by Edith. For she was beautiful in her own style - lots of hair and a strong face, trailing Liberty dresses, ropes of beads and dozens of bangles on her arm, incessant cigarettes in a long holder - and the parties she and Hubert gave were famous, with huge meals, wine and games played all over the house."

Edith Nesbit was a regular lecturer and writer on socialism throughout the 1880s. However she gave less time to these activities after she published The Story of the Treasure-Seekers (1899). Julia Briggs has pointed out: "With the creation of Oswald Bastable, she knew that she had discovered a highly original way of writing about and for children, and from this point in her career she never looked back. She now invented the children's adventure story, more or less single-handed, adding to it fantasy, magic, time-travel, and a delightful vein of subversive comedy. The next ten years or so saw the publication of all her major work, and in the mean time she was also composing poems, plays, romantic novels, ghost stories, and tales of country life."

Other books by Nesbit included, The Wouldbegoods (1901), Five Children and It (1902), The Pheonix and the Carpet (1904), The New Treasurer-Seekers (1904), The Railway Children (1906) and The Enchanted Castle (1907). A collection of her political poetry, Ballads and Lyrics of Socialism, was published in 1908.

Claire Tomalin has argued: "Nesbit's books were hugely popular with children and adults, admired by writers as various as Kipling and Wells, and have remained in print ever since... Their recurring theme of lost and found fathers addresses itself to children's deep fears and hopes. Another theme, that of the wish granted that turns out to be awkward or frightening, goes similarly straight to the heart of the fantasies and semi-conscious terrors of many children."

Hubert Bland died after suffering a heart attack on 14th April 1914. In the summer of 1916 she met Thomas Terry Tucker (1856–1935), a widowed marine engineer who shared her socialistic political views. She told her sister, "I feel as though someone had come and put a fur cloak round me.". Her children disapproved of the relationship because he "spoke with a broad cockney accent and never wore a collar" but she was deeply in love and they were married on 20th February 1917 at St Peter's Roman Catholic Church in Woolwich.

On this day in 1938 King George VI writes a letter to Queen Mary complaining about those rejecting appeasement. "I am sure you feel as angry as I do at people croaking as they do at the P.M.'s action, for once I agree with Lady Oxford who is said to have exclaimed as she left the House of Commons yesterday, 'He brought home peace, why can't they be grateful'. It is always so easy for people to criticise when they do not know the ins and outs of the question. George VI was a great supporter Neville Chamberlain and his foreign policy.

Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother (30th September 1938)

On this day in 1939, Winston Churchill calls for a military alliance with the Soviet Union: "Ten or twelve days have already passed since the Russian offer was made. The British people, who have now, at the sacrifice of honoured, ingrained custom, accepted the principle of compulsory military service, have a right, in conjunction with the French Republic, to call upon Poland not to place obstacles in the way of a common cause. Not only must the full co-operation of Russia be accepted, but the three Baltic States, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, must also be brought into association. To these three countries of warlike peoples, possessing together armies totalling perhaps twenty divisions of virile troops, a friendly Russia supplying munitions and other aid is essential. There is no means of maintaining an eastern front against Nazi aggression without the active aid of Russia. Russian interests are deeply concerned in preventing Herr Hitler's designs on eastern Europe. It should still be possible to range all the States and peoples from the Baltic to the Black sea in one solid front against a new outrage of invasion. Such a front, if established in good heart, and with resolute and efficient military arrangements, combined with the strength of the Western Powers, may yet confront Hitler, Goering, Himmler, Ribbentrop, Goebbels and co. with forces the German people would be reluctant to challenge."

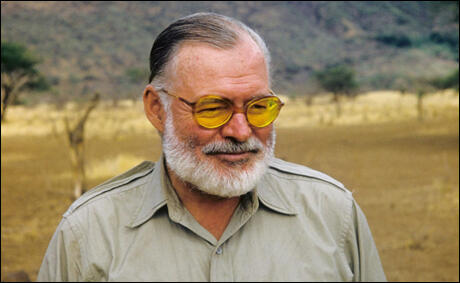

On this day in 1953 Ernest Hemingway wins the Pulitzer Prize for The Old Man and the Sea (1952). Two years later Hemingway won the Nobel Prize for literature. Hemingway, depressed by failing artistic and physical powers, committed suicide on 2nd July, 1961. According to his friend, Alvah Bessie: "Ernest Hemingway committed suicide on 2 July 1961. He had apparently felt that he was through - both as a writer and a man." A Moveable Feast, a memoir of his years in Paris after the First World War, and two novels, Islands in the Stream and The Garden of Eden, were published after his death.

On this day in 1979 Margaret Thatcher becomes the first female Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. Thatcher's government continued the monetarist policies introduced by Denis Healey. As Anne Perkins has pointed out: "Although monetarism had already been forced upon the preceding Labour government by the International Monetary Fund, under Thatcher it was presented as a crusade... In the first budget of the administration, VAT was nearly doubled to 15% while personal taxes were slashed – the top rate of income tax from 83% to 60%, and the standard rate from 33% to 30%. Over the next 10 years, the standard rate came down to 25%, and the top rate to 40%."

Inflation was reduced but unemployment doubled between 1979 and 1980. In 1981, Sir Geoffrey Howe, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, announced further public spending cuts. Larry Elliott has argued: "To her detractors, Thatcher is the prime minister who wiped out more than 15% of Britain's industrial base with her dogmatic monetarism, squandered the once-in-a-lifetime windfall of North Sea oil on unemployment pay and tax cuts, and made the UK the unbalanced, unequal country it is today." During this period public opinion polls suggested that Thatcher was the most unpopular prime minister in British history.

Thatcher's government also raised money by a programme of privatization. This included the denationalization of British Telecom, British Airways, Rolls Royce and British Steel. The political commentator, Anne Perkins, has suggested: "Privatisation, which came to be a fundamental of the Thatcherite mission, was only hinted at in 1979, and in the depression of the early 1980s caution prevailed. When the ailing nationalised motor manufacturer British Leyland ran into trouble in early 1980, Joseph, then Thatcher's industry minister, bailed it out like a Heathite. Nonetheless, in 1980-81 more than £400m was raised from selling shares in companies such as Ferranti and Cable and Wireless. Later came North Sea oil (Britoil) and British Ports, and from late 1984 the major sales of British Telecom, British Gas and British Airways, culminating at the end of the decade in water and electricity. By this time these sales were raising more than £5bn a year."

On 2nd April 1982 Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands. The following day the United Nations passed resolution 502 demanding that Argentina withdrew from the Falklands. On 5th April the British Navy left Portsmouth for the Falklands. Britain declared a 200 mile exclusion zone around the Falklands and on 2nd May 1982 the Argentinean battleship General Belgrano was sunk. Two days later HMS Sheffield was hit by an exocet missile. British troops landed on the Falkland Islands at San Carlos on 21st May. Fighting continued until Port Stanley was captured and Argentina surrendered on 14th June 1982.

According to Ipsos UK Research in March 1981 only 16% of the public asked were satisfied with Margaret Thatcher as prime minister. This was the lowest rating since this kind of information was recorded. However, after the recapture of the Falklands 59% were satisfied with her performance. This was higher than any prime minister had achieved. Only Tony Blair's government, for a few months when he first took office and later briefly after the 9/11 attacks, ever had similar satisfaction ratings in Ipsos polls. The Falklans War helped Thatcher and the Conservative Party to win the 1983 General Election with a majority of 144.

On this day in 1980 Josip Broz Tito, died. Tito had several disagreements with Joseph Stalin and in 1948 he took Yugoslavia out of the Comintern and pursued a policy of "positive neutralism". Influenced by the ideas of his vice-president, Milovan Djilas, Tito attempted to create a unique form of socialism that included profit sharing workers' councils that managed industrial enterprises. Although created President for life in 1974, Tito established a unique system of collective, rotating leadership within the country.

On this day in 2002 the death of Barbara Castle is announced. She had died at her home in Buckinghamshire on 3rd May 2002.

Barbara Betts, the daughter of a tax inspector, was born in Bradford in 1910. Her father was a member of the Independent Labour Party and she was converted to socialism at an early age. Castle was educated at Bradford Girls' Grammar School. Barbara wrote that "the girl's parents were all rich, and the dainty frocks that the pupils wore did credit to the school's reputation of beauty and culture throughout."

Barbara became friends with Mary Hepworth, a cash-desk girl who shared her committment to socialism. "Barbara had some sort of an intellectual battle with her father, who never felt that she did her brains justice. I think he expected too much from her at her age."

In 1929 Barbara and Mary attended the Independent Labour Party conference in Derby. That year she was the school's Labour candidate in the mock election to coincide with the 1929 General Election. Her campaign was highly impressive and one girl said that "she made you want to listen to her". She became head girl and later that year won a place at St. Hugh's College.

One of her best friends at Oxford University was Olive Shapley. She pointed out that she was very popular and had "a comet-like tail of men in pursuit". Olive later recalled: "She was small and pretty, and I think she disliked being pretty. She had these beautiful fine features, lovely little nose and beautiful skin and hair, and I think she would rather have been more dramatic looking."

In 1932 Barbara began an affair with William Mellor. As Anne Perkins, the author of Red Queen (2003) has pointed out: "Mellor was already forty-four, only six years younger than her father and exactly twice Barbara's age. He was glamorous, confident and married, with a baby son. He became her mentor, her alternative father, a man who loved her totally and compellingly." Castle later admitted "Mellor was in many ways much like my father. They were of that same bigness. He was about my father's generation, a bit younger than my father but considerably older than I was."

William Mellor introduced Castle to Stafford Cripps, the leader of the left-wing of the Labour Party. Other members of this group included Aneurin Bevan, Ellen Wilkinson, Frank Wise, Jennie Lee, Harold Laski, Frank Horrabin, Barbara Betts and G. D. H. Cole. In 1932 the group established the Socialist League.

With the rise of Adolf Hitler in Nazi Germany, Castle and Mellor became convinced that the Labour Party should establish a United Front against fascism with the Communist Party of Great Britain and the Independent Labour Party. In April 1934 Mellor had a meeting with Fenner Brockway and Jimmy Maxton, two leaders of the ILP, "to talk over ways and means of securing working-class unity". He also had meetings with Harry Pollitt, the General Secretary of the Communist Party of Great Britain.

William Mellor told Castle in 1934: "In the end I am a socialist and an agitator because I want a free world in which human relationships shall be free from the constrictions and restraints imposed by... and taboos that spring from, religious... fears. I'm a politician only because this world as it is kills individuality, destroys freedom and fetters human beings... We may have to go through hell to get there but even that wouldn't be too big a price to pay."

In the 1935 General Election Mellor, was the Labour candidate in Enfield. Mellor wrote to his mother that Barbara Castle was of great help in his campaign: "Barbara is working like a trojan and speaking like an angel." Mellor was defeated but Castle pointed out that he added five thousand to the Labour vote on "a 100% left-wing programme".

Castle continued to attack the leadership of the Labour Party for not establishing a United Front with the Independent Labour Party and Communist Party of Great Britain and along with William Mellor and Stafford Cripps established the Socialist League. This upset the leaders of the Trade Union Congress and as they still controlled the Daily Herald Mellor was warned that he was in danger of losing his job. When he refused to back-down he was sacked in March 1936.

William Mellor now established the Town and County Councillor, a journal for Labour supporters in local government. He appointed Barbara Betts, on £4 a week, as one of the journalists on the paper. He also gave work to Michael Foot, who had just left university.

In January 1937 Stafford Cripps and George Strauss decided to launch a radical weekly, The Tribune, to "advocate a vigorous socialism and demand active resistance to Fascism at home and abroad." Mellor was appointed editor and others such as Barbara Betts, Aneurin Bevan, Ellen Wilkinson, Harold Laski, Michael Foot, Winifred Batho and Noel Brailsford agreed to write for the paper.

William Mellor wrote in the first issue: "It is capitalism that has caused the world depression. It is capitalism that has created the vast army of the unemployed. It is capitalism that has created the distressed areas... It is capitalism that divides our people into the two nations of rich and poor. Either we must defeat capitalism or we shall be destroyed by it." Stafford Cripps wrote encouragingly after the first issue: "I have read the Tribune, every line of it (including the advertisements!) as objectively as I can and I must congratulate you upon a very first-rate production.''

Barbara continued to support the idea of a United Front against fascism. On 17th May 1937 she said at a meeting in Leicester: "The Socialist League stands unrepentant before the Labour movement for its action in entering into agreement with the Independent Labour Party and Communist Party of Great Britain to conduct a campaign for unity of the working class against the National Government. It stands unrepentant because it believes the workers of Great Britain cannot at this crucial moment afford the luxuries of apathy, drift and division.... Driven into a corner by the weakness of its own arguments the National Executive has resurrected as its one objection the finances of the Unity Campaign."

In October 1937, Barbara was sent by The Tribune to report on the situation in the Soviet Union. "Many a short-sighted visitor to Russia has been shocked by external evidence of poverty... But the Russians don't get alarmed. The coming of the luxurious they know is all a matter of time. And in the meanwhile they enjoy what capitalism can't offer its workers: security today, hope of abundance tomorrow... here is no shadow of slump and unemployment - only an insatiable demand for more and yet more workers."

Stafford Cripps declared that the mission of the Socialist League and The Tribune was to recreate the Labour Party as a truly socialist organization. This soon brought them into conflict with Clement Attlee and the leadership of the party. Hugh Dalton declared that "Cripps Chronicle" was "a rich man's toy". Threatened with expulsion, in May 1937 Cripps agreed to abandon the United Front campaign and to dissolve the Socialist League.

By 1938 Stafford Cripps and George Strauss had lost £20,000 in publishing The Tribune. The successful publisher, Victor Gollancz, agreed to help support the newspaper as long as it dropped the United Front campaign. When William Mellor refused to change the editorial line, Cripps sacked him and invited Michael Foot to take his place. However, as Mervyn Jones has pointed out: "It was a tempting opportunity for a 25-year-old, but Foot declined to succeed an editor who had been treated unfairly."

William Mellor now concentrated on editing the Town and County Councillor. Rumours about Mellor began to circulate. Barbara wrote to her mother claiming that Victor Gollancz was behind these stories: "Gollancz, we have every reason to believe, is spreading fairy stories about the matter all over the country, and we are helpless."

In April 1942 Mellor wrote to Barbara: "I have loved you since the first day I saw you. And after ten years - it's nearly that, sweet - rich with lovely memories and black with the recollection of my own cowardice in not following the course love set, I know now that my love is deeper, more compelling, more understanding and finer, I hope, than at any time." However, he still refused to divorce his wife and marry Barbara.

In the summer of 1942 William Mellor was told by his doctor that he had a stomach ulcer. He was told that he must take six months rest or to have an operation. Mellor felt that his job was too insecure to take too much time off so he opted for an operation. At first it seemed to go well, but then complications set in. On 8th June, 1942, two weeks after the operation, William Mellor died.

In 1943 she made her first speech at the national conference of the Labour Party. This included an attack on the leadership of the party for not doing enough to force the government to implement the Beveridge Report. In July 1944 she married the journalist, Ted Castle.

Castle worked as housing correspondent of the Daily Mirror during the Second World War and in the 1945 General Election she was elected to represent Blackburn in the House of Commons. Soon afterwards Stafford Cripps, the Minister of Trade, appointed Castle as one of his aides. Over the next few years she was associated with the left-wing of the party led by Aneurin Bevan.

Castle was Chairperson of the Labour Party (1958-59) and after the party won the 1964 General Election the new prime minister, Harold Wilson, appointed her as Minister of Overseas Development (1964-65) and Minister of Transport (1965-68). In this post she introduced the 70 mph speed limit, breathalyzer tests for suspected drunken drivers and compulsory seat belts. Wilson pointed out in his autobiography: Memoirs: 1916-1964 (1986): "Barbara proved an excellent minister. She was good at whatever she touched. I doubt if any member of the Cabinet worked longer hours or gave more productive thought to what they were doing."

In 1968 Castle became Secretary of State for Employment and Productivity (1968-70) and attempted to introduce the government's controversial prices and incomes policy. The publication of the white paper, In Place of Strife (1969) brought her into conflict with the trade unions and the left-wing of the Labour Party. Her critics were particularly hostile to the proposal for compulsory strike ballots. As Anne Perkins has pointed out: "Barbara's stock crashed to earth. But the ramifications went far beyond personal disaster. The episode accelerated a renewed alienation between party activists and the Labour leadership."

Castle lost office when the Conservative Party won the 1970 General Election. When the Labour Party returned to power in 1974 she became Secretary of State for Social Services (1974-76). In this post she introduced child benefit and established the link between pensions and earnings. She also attempted to bring an end to pay beds in the NHS. This led to doctors taking industrial action which closed accident and emergency wards in hospitals. When Jim Callaghan replaced Harold Wilson as prime minister he sacked Castle by claiming she was too old too serve in the cabinet.

Castle was a member of the European Parliament (1979-89) where she served as vice-chairperson of the Socialist Group (1979-86) and in 1990 joined the House of Lords. Over the next few years she successfully campaigned to restore the link between pensions and earnings. As The Times pointed out: "Lady Castle of Blackburn, a passionate socialist of the old school, kept up her scrutiny of government well into her eighties. At the 1999 Labour Party conference she savaged ministers for tying pensions to inflation, a move that led to the infamous 75p increase."

Castle published her political diaries and an autobiography, Fighting All the Way (1993).