On this day on 3rd May

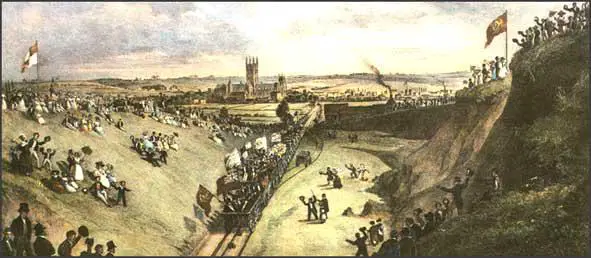

On this day in 1830 the Canterbury and Whitstable Railway is opened. In 1822 William James began to make plans for a railway between Canterbury and Whitstable. However, James went bankrupt in 1824 and it was not until 1830 that the line opened. Most of the six miles were laid out as cable-operated inclined planes. Robert Stephenson supplied the locomotive, Invicta, to operate over the one and a quarter miles of level track at Whitstable. When it was opened on 3rd May, 1830, the Invicta became the first steam locomotive in the world to haul regular passenger trains.

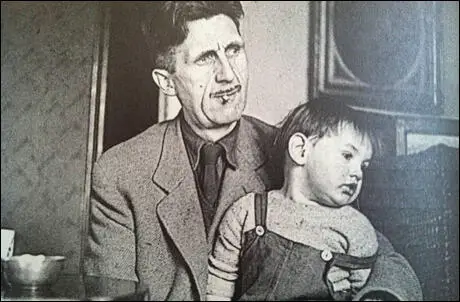

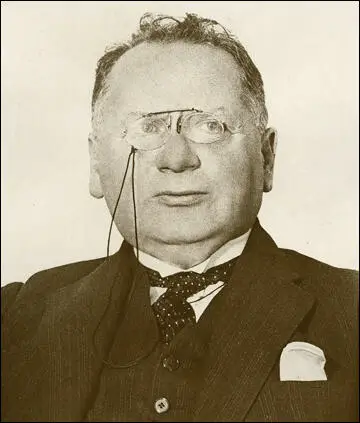

On this day in 1849 Jacob Riis, the third of fifteen children, was born in Ribe, Denmark. He worked as a carpenter in Copenhagen before emigrating to the United States in 1870. Unable to find work, he was often forced to spend the night in police station lodging houses.

Riis did a variety of menial jobs before finding work with a news bureau in New York City in 1873. The following year he was recruited by the South Brooklyn News. In 1877 Riis became a police reporter for the New York Tribune. Aware of what it was like to live in poverty, Riis was determined to use this opportunity to employ his journalistic skills to communicate this to the public. He constantly argued that the "poor were the victims rather than the makers of their fate".

In 1888 Riis was employed as a photo-journalist by the New York Evening Sun. Riis was among the first photographers to use flash powder, which enabled him to photograph interiors and exteriors of the slums at night. He also became associated with what later became known as muckraking journalism.

In December, 1889, an account of city life, illustrated by photographs, appeared in Scribner's Magazine. This created a great deal of interest and the following year, a full-length version, How the Other Half Lives, was published. The book was seen by Theodore Roosevelt, the New York Police Commissioner, and he had the city police lodging houses that were featured in the book closed down.

Harold Evans, the author of The American Century: People, Power and Politics (1998) has pointed out: "Jacob Riis estimated that Dickensian London had 175,816 people living on every square mile of its worst slums but New York's Lower East Side by the nineties in contrast, had about 290,000 per square mile, making it perhaps the worst slum in the history of the Western world.... He records a tenement block with 1,324 Italian immigrants living in a total of 132 rooms. In one 12-by-12-foot room he found five families, 20 people, with two beds between them. One third of the entire city population - about 1.2 million - lived in 43,000 tenement houses like these, without running water or indoor flush toilets... Some 40 percent of them had tuberculosis. One third of all their babies died before their first birthday."

Over the next twenty-five years Jacob Riis wrote and lectured on the problems of the poor. This included magic lantern shows and one observer noted that "his viewers moaned, shuddered, fainted and even talked to the photographs he projected, reacting to the slides not as images but as a virtual reality that transported the New York slum world directly into the lecture hall."

The work of Riis inspired Lincoln Steffens, the man considered to be the "godfather" of investigative journalism argued in Autobiography (1931): "He (Riis) not only got the news; he cared about the news. He hated passionately all tyrannies, abuses, miseries, and he fought them. He was a terror to the officials and landlords responsible, as he saw it, for the desperate condition of the tenements where the poor lived. He had exposed them in articles, books, and public speeches, and with results. All the philanthropists in town knew and backed Riis, who was able then, as a reformer and a reporter, too, to force the appointment of a Tenement House Commission that he gently led and fiercely drove to an investigation and a report which - followed up by this terrible reporter-resulted in the wiping out of whole blocks of rookeries, the making of small parks, and the regulation of the tenements."

Riis also wrote over a dozen books including Children of the Poor (1892), Out of Mulberry Street (1898), an autobiography, The Making of An American (1901), The Battle With the Slum (1902), and Children of the Tenement (1903). Jacob Riis died in Barrie, Massachusetts, on 26th May, 1914.

On this day in 1912 Piotr Petrovich Belousov was born in Berdyansk. A follower of Isaac Brodsky, one of the founders of the Socialist Realist art movement. After graduating from the Repin Institute of Arts in 1939, he went to Brodky's workshop.

Over the next few years he produced a series of portraits and historical paintings devoted to the life of Lenin. The most famous of these was on the assassination attempt by Fanya Kaplan on Lenin.

In 1939 he was appointed as a teacher at the Repin Institute of Arts. A member of the Leningrad Union of Artists he became Professor and Head of Department of Drawing in 1956 and the People's Artist of the Russian Federation in 1978. Piotr Petrovich Belousov died in Leningrad in 1989. 1914.

On this day in 1919 Pete Seeger was born in New York City. He later wrote: "My ancestors came to this country because they didn't want to answer questions put to them by the then Un-English committees. One of them, Elder Brewster, was on the Mayflower with Governor Bradford, one of the leaders of the Plymouth Colony. His descendants that came my way were staunch upholders of independence among the colonists. Not one was a royalist.... These ancestors of mine were all subversives in the eyes of the established government of the British colonies. If they had lost the War of Independence, they might have been hung."

His father, Charles Louis Seeger, was a musicologist who taught at Berkeley University. He held left-wing views and was sympathetic to the International Workers of the World (IWW). Seeger lost his job when he opposed United States involvement in the First World War. Seeger told his dean that Germany and England were both imperialist powers, and as far as he was concerned, they could fight each other to a stalemate. According to his friends, losing his professorship for his activism affected him profoundly.

His mother, Constance de Clyver Edson, also held radical political views and was a follower of Norman Thomas, a pacifist and member of the American Socialist Party, Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), and National Civil Liberties Bureau (NCLB) who refused to fight in the war as he believed it was an "immoral, senseless struggle among rival imperialisms". Constance was also a musician and played the violin in concerts.

Charles and Constance Seeger and their children moved to Patterson to live with his parents. His father had made a small fortune in sugar-refining in Mexico. Pete Seeger later recalled: "Talk about ivory towers, I grew up in a woodland tower... I knew all about plants and could identify birds and snakes, but I did not know that anti-Semitism existed... My contact with black people was literally nil... If someone asked me what I was going to be when I grew up, I'd say farmer or forest ranger."

Seeger was sent to boarding school at four. In 1927 his parents divorced. Seeger had a difficult relationship with his mother. She was keen for him to take music lessons but at the time he showed little interest in playing the piano or the violin. Seeger admitted: "My father was the one person I really related to. For good or bad, I had very few relationships with anyone else. I was cordial with everybody - I didn't like to fight and I didn't like to argue. My brothers? We got along; but they were much older than me - six and seven years older - and in a different world."

Charles Louis Seeger and his new wife, Ruth Crawford Seeger, went to live in Greenwich Village. He joined the Composers Collective that appeared at the DeGeyter Club. They also sung their songs on picket and unemployment lines. During one holiday his father took him to hear a lecture by Aaron Copland. He was impressed by Copland's enthusiasm and passion. Seeger later recalled: "I got the feeling that here were people out to change the world. The world might be corrupt, but they were confident they could change it."

In 1932 entered high school at Avon Old Farms. During this period Seeger read widely. This included journalists such as Lincoln Steffens, George Seldes, Carl Sandburg and Michael Gold and was an avid reader of New Masses. Seeger started his own newspaper, the Avon Weekly. He got into trouble with his headmaster, Commander Hunter, when he published an anonymous letter on anti-Semitism that had been written by a Jewish student at the school. "There's a lot of talk about democracy and freedom in this country and in the school, but when it comes down to the way people actually act, face it, they don't always live by their pretty words." Under the threat of banning the newspaper, Seeger, named the boy who had written the letter.

Pete Seeger's father became an administered music programs for the Farm Security Administration. In 1935 he moved to Montgomery County, Maryland. During this period, when he was staying with his father, he began listening to local radio and discovered he liked folk music. "I liked the strident vocal tone of the singers, the vigorous dancing. The words of the folk songs had all the meat of life in them. Their humor had a bite, it was not trival. Their tragedy was real, not sentimental. In comparison, most of the pop music of the thirties seemed to be weak and soft, with its endless variations on Baby, baby I need you." Pete purchased a five-string banjo and taught himself to play the instrument.

Seeger went to Harvard University in 1937. He wanted to study journalism but they did not teach the subject so he decided on sociology instead. He was tempted to join the Abraham Lincoln Brigade that was fighting in the Spanish Civil War. He did not like the idea of fighting but insisted that "if someone had offered me a job as a reporter, though, I'd have jumped at it." Therefore he concentrated on raising money for the cause. He also founded his own radical newspaper, The Harvard Progressive, with Arthur Kinoy and joined the Young Communist League.

Seeger was in the same year as John F. Kennedy. However, unlike Kennedy he did not complete his degree. It has been said that whereas Kennedy was Harvard's most famous graduates, Seeger was probably its best-known dropouts. He left university in 1938 and attempted to make a living as a journalist. "College was fine for those who want it, but I was just not interested; I wanted to be a journalist."

In 1939 Charles Seeger introduced his son to Alan Lomax. He arranged for him to meet Molly Jackson, the composer of I Am a Union Woman and Huddie Leadbelly. With their encouragement he began taking his music more seriously. His first concert performance was on 3rd March 1940. It was a benefit for California migrant workers. Other singers on the show included Josh White, Woody Guthrie, Burl Ives, Jackson and Leadbelly. Seeger was especially impressed by Guthrie: "Woody Guthrie just ambled out, offhand and casual... a short fellow complete with a western hat, boots, blue jeans, and needing a shave, spinning out stories and singing songs he'd made up... He was a big piece of my education."

In December 1940 Seeger joined together with Woody Guthrie, Lee Hayes, Pete Hawes and Millard Lampell to form the Almanac Singers. They specialized in songs advocating an anti-war, anti-racism and pro-union philosophy. Lampell later explained: "I was doing all kinds of writing before I hooked up with Pete and Woody and Lee. I had read Lee's satirical stories in the New Republic about his father's circuit-riding days, and he had read my articles there. I hadn't even played an instrument as a kid, let alone thought of writing lyrics. But Lee and I took an apartment together, and the group got going."

David King Dunaway, the author of How Can I Keep From Singing (1985), has argued: "The Almanac Singers didn't want all-expenses-paid trips to Hollywood; union rallies were what they craved. They opposed war and promoted unions the way the early Christians believed in the Church." Performers who sang with the group at various times included Sis Cunningham, Bess Lomax Hawes, Cisco Houston, Josh White, Burl Ives and Sam Gary. The music collective issued a popular record, Talking Union in 1941.

It was claimed that the Almanac Singers were sympathetic to the views of the American Communist Party and gave support to the government of Joseph Stalin. The singer, Billy Bragg, has pointed out: "Seeger was criticised as a Stalin apologist, but he was honest about it and regretted his own naiveté. Like many at that time, he saw that the idealism that seemed to manifest itself in the USSR had been totally undermined by totalitarianism." Seeger told The Washington Post in 1994: “I apologize for once believing Stalin was just a hard driver, not a supremely cruel dictator. I ask people to broaden their definition of socialism. Our ancestors were all socialists: You killed a deer and maybe you got the best cut, but you wouldn’t let it rot, you shared it. Similarly, I tell socialists, every society has a post office and none of them is efficient. No post office anywhere invented Federal Express.”

The Almanac Singers mainly followed the party line and after the Nazi-Soviet Pact sang songs against involvement in the Second World War. They were therefore put in a very difficult situation when Adolf Hitler ordered the invasion of the Soviet Union on 22nd June, 1941. They now stopped singing peace songs and concentrated on other political issues such as The Ballad of Harry Bridges. When J. Edgar Hoover heard about the group he ordered that the members should be investigated for sedition.

The singer, Earl Robinson, often performed with Seeger. "Pete was superb with the banjo... Pete would stand up in front of an audience and really get them going, and in the enthusiasm of the moment, he'd tear off about twelve seconds of totally brilliant cadenza-type banjo; music that would stand up on any concert stage." Millard Lampell later recalled: "He (Pete Seeger) would get up in the morning, and before he'd eat or anything, he'd reach for the banjo and begin to play, sitting on his bed in his underwear... Back then, Pete had enormous energy. He wasn't the greatest banjo player, he didn't have the greatest voice, but there was something catchy about him... It was a time when the left wing was very romantic about America; in literature, these were the days of Carl Sandburg, Archibald MacLeish and Stephen Benet. Then suddenly it was as if the music of America had arrived."

On 7th December, 1941, Pearl Harbor was attacked and the United States entered the war. Alan Lomax warned Seeger that he should bring an end to the Almanac Singers as anti-war songs were not merely inappropriate, they were treasonous. Seeger also had the problem of having a girlfriend, Toshi Ohta, who had a Japanese father. Her father, Takashi Ohta, was arrested by the FBI but he was not interned.

The Almanacs now concentrated on writing anti-Nazi songs. The most successful of these was The Sinking of Reuben James, the story of the ninety-five people drowned in the first American ship torpedoed in the Second World War. They were even hired by the United States Office of War Information to perform for troops as the government understood the value of songs in building morale. As David King Dunaway pointed out: "When the Almanacs had sung peace songs, critics had called it propaganda; now they sang war songs, the government styled it patriotic art." On 14th February, 1942, the Almanacs played for nearly thirty million radio listeners at the opening of a new series, This Is War.

Pete Seeger joined the United States Army Airforce in June 1942. He worked on airplane engines at Kessler Air Force Base in Biloxi, Mississippi. When he was on leave he married Toshi Ohta in a small church in Greenwich Village on 20th July 1943. Soon afterwards he was transferred to Special Services Division based at Fort Meade in Maryland. In 1944 he was sent to Saipan to entertain the troops.

Seeger arrived back in America in 1945. Bess Lomax Hawes pointed out: "When Pete came back from the war he was a very different man. He had matured physically and became a stronger singer. Now he was physically vibrant. He'd always been tense, lean, and bony, but the years of physical activity had put some weight on him. He was as hard as nails... He'd worked for all kinds of audiences and come back with People's Songs in his head and the same burning intensity. He had a national idea in mind now."

On 31st December, 1945, Seeger decided to establish People's Songs Incorporated (PSI). Some of his friends, including Alan Lomax, Lee Hayes, Woody Guthrie, Millard Lampell, Burl Ives, Josh White, Sis Cunningham, Bess Lomax Hawes, Cisco Houston, Moe Asch, Tom Glazer, Sonny Terry, Zilphia Horton and Irwin Silber agreed to support the venture. Seeger was asked in January 1946 what was the purpose of the company: "Make a singing labor movement. I hope to have hundreds, thousands, tens of thousands of union choruses. Just as every church has a choir, why not every union?"

The organization published a weekly newsletter, People's Song Bulletin, with songs, articles, and announcements of future performances. After two months the PSI had over a thousand paid members in twenty states. In the New Masses Seeger pointed out: "When a bunch of people are seen walking down the street singing, it should go almost without saying that they are a bunch of union people on their way home from a meeting... Music, too, is a weapon." Within a few months the organization had two thousand members.

Aaron Copland, Leonard Bernstein, Dorothy Parker, Oscar Hammerstein II, John H. Hammond, Sam Wanamaker and Harold Rome gave permission for their names to be added to the masthead of People's Song Bulletin. Membership continued to increase and Seeger took an office in Times Square. This success was noted by J. Edgar Hoover and he instructed FBI officers to open a file on the PSI. Maurice Duplessis, the Governor of Quebec, ordered that PSI publications to be seized, and declared the song Joe Hill was subversive. When he heard the news Seeger issued a statement that included: "Do you think, Mr. Duplessis, you can escape the judgment of history? Long after the warmakers are relegated to the history books... people's music will be sung by the free peoples of earth."

Seeger was supporter of Henry Wallace and the Progressive Party candidate in the presidential election of 1948. On 30th August, 1948, Seeger and Paul Robeson appeared with Wallace in Burlington, North Carolina. Seeger later recalled: "There were times when a song lightened the atmosphere. I think it probably helped prevent people from getting killed. It was a very - touch and go proposition, that tour. A number of people thought Wallace was going to be assassinated... The police allowed some of the Ku Klux Klan to get away - with throwing things. Once they found out they could get away with that, then they really descended."

David King Dunaway has pointed out: "Monday morning, August 30, 1948, fifteen cars in Wallace's contingent brought Seeger and the candidate to the textile town of Burlington, North Carolina. A grim mood hung over the entourage: The night before, a supporter had been stabbed twice by anti-Wallace crowds. A hostile throng of 2,500 awaited the caravan. It took four policemen to clear the road for the automobiles to reach the public square.... The driver of the lead car, Marge Frantz, was an immediate target. The sight of blacks and whites in the same convertible (the top fortunately rolled up) sent a shock wave through the already excited crowd. A few cars back, Pete sat guarding his banjo and guitar. The angry Southerners crawled onto the hood of his car and peered down inside as it slowed to a halt. The mob started banging on the car doors, and the shell of metal must have seemed awfully thin.

He waited coolly as the crowd pressed in, yelling obscenities and 'Go back to Russia.' No one seemed to be in the mood for a sing-along. According to the plan, Seeger was supposed to leave the car, wait while a mike was positioned, and lead the crowd in group singing. But when he stuck his head out, the eggs started to fly. One hit Wallace, spattering his white shirt. It was clear no mike would be set up... There wasn't even time to tune up, when no amount of banjo picking was going to stop the cold war."

Harry S. Truman and his running mate, Alben W. Barkley, polled more than 24 million popular votes and 303 electoral votes. His Republican Party opponents, Thomas Dewey and Earl Warren, won 22 million popular votes and 189 electoral votes. Storm Thurmond ran third, with 1,169,032 popular and 39 electoral votes. Wallace was last with 1,157,063 votes. Nationally he got only 2.38 per cent of the total vote.

Seeger joined Ronnie Gilbert, Lee Hays and Fred Hellerman to form The Weavers in November 1948. The group took its name from a play by Gerhart Hauptmann, called Die Weber (The Weavers) about a strike in Silesia in 1892. He also invested $1,700 in 17 acres of land overlooking the Hudson River in Beacon, Dutchess County. He built a log cabin there and it became his permanent home for the rest of his life.

They signing a recording deal with Decca and on 4th May, 1950, the group recorded Tzena, Tzena and Goodnight Irene, a song written by Seeger's old friend, Huddie Leadbelly. For censorship reasons the chorus was changed from "I'll get you in my dreams" to "I'll see you in my dreams". The record was a massive hit. Seeger later commented: "I remember laughing when I walked down the street and heard my own voice coming out of a record store." They were offered a weekly national TV spot on NBC and were paid $2,250 a week to appear at the Beacon Theater on Broadway.

The Weavers had a number of hit songs including Wimoweh, The Roving Kind, On Top of Old Smoky, The Midnight Special, Pay Me My Money Down and Darling Corey. In their shows they sung left-wing songs such If I Had a Hammer, that their record company felt that the general public would not accept. Most of his friends said that success did not change Seeger. However, Lee Hays, did say that it increased his "arrogant modesty".

On 6th June, 1950, Harvey Matusow sent a message to the FBI that they should keep a close watch on The Weavers as the leader of the group, Pete Seeger, was a member of the American Communist Party. This was untrue as Seeger had left the party soon after the war. In fact, the agency had been monitoring Seeger since 1940. J. Edgar Hoover now leaked this FBI file to Frederick Woltman, of the New York World Telegram. He published an article revealing that the Weavers were the first musicians in American history to be investigated for sedition.

Roy Brewer, a close friend of Ronald Reagan, was appointed to the Motion Picture Industry Council. Brewer commissioned a booklet entitled Red Channels. Published on 22nd June, 1950, and written by Ted C. Kirkpatrick, a former FBI agent and Vincent Hartnett, a right-wing television producer, it listed the names of 151 writers, directors and performers who they claimed had been members of subversive organisations before the Second World War but had not so far been blacklisted. People listed included Pete Seeger, Larry Adler, Stella Adler, Leonard Bernstein, Marc Blitzstein, Joseph Bromberg, Lee J. Cobb, Aaron Copland, John Garfield, Howard Da Silva, Dashiell Hammett, E. Y. Harburg, Lillian Hellman, Burl Ives, Zero Mostel, Arthur Miller, Betsy Blair, Dorothy Parker, Philip Loeb, Joseph Losey, Anne Revere, Gale Sondergaard, Howard K. Smith, Louis Untermeyer and Josh White.

Three days after the booklet was published the Korean War erupted. The list of entertainers were now seen as America's mortal enemies. NBC immediately cancelled its contract with the Weavers. Although the Weavers had sold over four million records, radio stations now stopped playing their music. They were also banned from appearing on national television. However, despite this attempt to take them out of circulation, in 1951 they still had hits with Kisses Sweeter than Wine and So Long It's Been Good to Know You.

On 6th February, 1952, Harvey Matusow testified in front of the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) that Seeger was a member of the American Communist Party. Matusow admitted in his autobiography, False Witness (1955) that this was untrue but Seeger said this ended the career of The Weavers: "Matusow's appearance burst like a bombshell... We had started off singing in some very flossy night-clubs... Then we went lower and lower as the blacklist crowded us in. Finally, we were down to places like Daffy's Bar and Grill on the outskirts of Cleveland." Despite not being a member of the party Seeger continued to describe himself as a “communist with a small ‘c.’ ”

It was another three years before Seeger was called before the HUAC. Frank Donner, a lawyer who defended several people who were called before the HUCA, wrote in The Un-Americans (1961): "He knows that the Committee demands his physical presence in the hearing room for no reason other than to make him a target of its hostility, to have him photographed, exhibited and branded... He knows that the vandalism, ostracism, insults, crank calls and hate letters that he and his family have already suffered are but the opening stages of a continuing ordeal... he is tormented by the awareness that he is being punished without valid cause, and deprived, by manipulated prejudice, of his fundamental rights as an American."

Seeger's lawyer, Paul Ross, advised him to use the Fifth Amendment defence (the right against self-incrimination). In the year of Seeger's subpoena, the HUAC called 529 witnesses and 464 (88 per cent) remained silent. Seeger later recalled: "The expected move would have been to take the Fifth. That was the easiest thing, and the case would have been dismissed. On the other hand, everywhere I went, I would have to face 'Oh, you're one of those Fifth Amendment Communists...' I didn't want to run down my friends who did use the Fifth Amendment but I didn't choose to use it."

Seeger had been struck by something that I.F. Stone had written in 1953: "Great faiths can only be preserved by men willing to live by them (HUAC's violation of the First Amendment) cannot be tested until someone dares invite prosecution for contempt." Seeger decided that he would accept Stone's challenge, and use the First Amendment defence (freedom of speech) even though he knew it would probably result in him being sent to prison. Seeger told Paul Ross : "I want to get up there and attack these guys for what they are, the worst of America". Ross warned him that each time the HUCA found him in contempt, he was liable to a year in jail.

The first day of the new HUAC hearings took place on 15th August 1955. Most of the witnesses were excused after taking the Fifth Amendment. Seeger's friend, Lee Hays, also evoked the Fifth Amendment on the second day of the hearings and he was allowed to go unheeded. Seeger was expected to follow his example but instead he answered their questions. When asked for details of his occupation, Seeger replied: "I make my living as a banjo picker - sort of damning in some people's opinion." However, when Gordon Scherer, a sponsor of the John Birch Society, asked him if he had performed at concerts organized by the American Communist Party he refused to answer.

Francis Walter, the chairman of the House of Un-American Activities Committee, told Seeger: "I direct you to answer". Seeger replied: "I am not going to answer any questions as to my association, my philosophical or religious beliefs or my political beliefs, or how I voted in any election or any of these private affairs. I think these are very improper questions for any American to be asked, especially under such compulsion as this." Seeger later recalled: "I realized that I was fitting into a necessary role... This particular time, there was a job that had to be done, I was there to do it. A soldier goes into training. You find yourself in battle and you know the role you're supposed to fulfill."

The HUAC continued to ask questions of this nature. Seeger pointed out: "I feel that in my whole life I have never done anything of any conspiratorial nature and I resent very much and very deeply the implication of being called before this Committee that in some way because my opinions may be different from yours, that I am any less of an American than anyone else. I am saying voluntarily that I have sung for almost every religious group in the country, from Jewish and Catholic, and Presbyterian and Holy Rollers and Revival Churches. I love my country very dearly, and I greatly resent the implication that some of the places that I have sung and some of the people that I have known, and some of my opinions, whether they are religious or philosophical, make me less of an American."

As a result of Seeger's testimony, on 26th July, 1956, the House of Representatives voted 373 to 9 to cite Seeger, Arthur Miller, and six others for contempt. However, Seeger did not come to trial until March, 1961. Seeger defended himself with the words: "Some of my ancestors were religious dissenters who came to America over three hundred years ago. Others were abolitionists in New England in the eighteen forties and fifties. I believe that my choosing my present course I do no dishonor to them, or to those who may come after me." He was found guilty and sentenced to 12 months in prison. After worldwide protests, the Court of Appeals ruled that Seeger's indictment was faulty and dismissed the case.

Pete Seeger told Ruth Schultz in 1989: "Historically, I believe I was correct in refusing to answer their questions. Down through the centuries, this trick has been tried by various establishments throughout the world. They force people to get involved in the kind of examination that has only one aim and that is to stamp out dissent. One of the things I'm most proud of about my country is the fact that we did lick McCarthyism back in the fifties. Many Americans knew their lives and their souls were being struggled for, and they fought for it. And I felt I should carry on. Through the sixties I still had to occasionally free picket lines and bomb threats. But I simply went ahead, doing my thing, throughout the whole period. I fought for peace in the fifties. And in the sixties, during the Vietnam war, when anarchists and pacifists and socialists, Democrats and Republicans, decent-hearted Americans, all recoiled with horror at the bloodbath, we came together."

His friend, Don McLean, explained how this case severely damaged his career: "Pete went underground. He started doing fifty dollar bookings, then twenty-five dollar dates in schoolhouses, auditoriums, and eventually college campuses. He definitely pioneered what we know today as the college circuit. He persevered and went out like Kilroy, sowing seeds at a grass-roots level for many, many years. The blacklist was the best thing that happened to him; it forced him into a situation of struggle, which he thrived on." Seeger's concerts were often picketed by the John Birch Society and other right-wing groups. He later recalled: “All those protests did was sell tickets and get me free publicity. The more they protested, the bigger the audiences became.”

Although freed from prison, the blacklisting of Seeger continued. Seeger's songs written and performed during this period often reflected his left-wing views and included We Shall Overcome, Where Have All the Flowers Gone, If I Had a Hammer, Guantanamera, The Bells of Rhymney and Turn, Turn, Turn. Seeger's biographer, David King Dunaway, has argued: "Pete's best political songs evoked not the bitterness of repression but the glory of its solution, the potential beauty of a world remade. His music couldn't overthrow a government, he had come to realize, but the children he sang for might begin the process."

Jon Pareles has pointed out in the New York Times: "Seeger was signed to a major label, Columbia Records, in 1961, but he remained unwelcome on network television. Hootenanny, an early-1960s show on ABC that capitalized on the folk revival, refused to book Mr. Seeger, causing other performers (including Bob Dylan, Joan Baez and Peter, Paul and Mary) to boycott it. Hootenanny eventually offered to present Mr. Seeger if he would sign a loyalty oath. He refused."

Seeger remained active in the protest movement. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee adopted his song, We Shall Overcome, during the 1960 student sit-ins a restaurants which had a policy of not serving black people. The students were often physically assaulted, but following the teachings of Martin Luther King they did not hit back. This non-violent strategy was adopted by black students all over the Deep South. Within six months these sit-ins had ended restaurant and lunch-counter segregation in twenty-six southern cities. Student sit-ins were also successful against segregation in public parks, swimming pools, theaters, churches, libraries, museums and beaches. The SNCC also sung the song during the 1961 Freedom Rides.

As well as the Civil Rights Movement Seeger was also involved in protests against the Vietnam War. As a result television stations refused to end the blacklisting of Seeger. Artists that had been inspired by the work of Seeger such as Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Tom Paxton, and Harry Belafonte, protested against this decision. It was not until 1967 that the Smothers Brothers managed to negotiate a guest appearance for Seeger on their TV program, The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour.

Pete Seeger and his wife Toshi Ohta, continued to live in a log cabin overlooking the Hudson River in Beacon, Dutchess County. They co-founded both the Hudson River Sloop Clearwater and its related musical offshoot, The Great Hudson River Revival (also known as the Clearwater Festival).They used the festival to rally public support for cleaning up the Hudson River. The Clearwater Festival now attracts more than 15,000 attendees to Croton Point Park each summer.

In 1979 The Weavers reunited for a concert at Carnegie Hall, filmed for the much-admired documentary, The Weavers: Wasn't That a Time (1982). Paul Buhle has commented that "the event found the media, including the New York Times, downright sentimental and perhaps a little guilty toward the formerly persecuted artists." Seeger continued to perform, often with his grandson, Tao Rodríguez-Seeger.

Seeger told The Washington Post in 1994: “I apologize for once believing Stalin was just a hard driver, not a supremely cruel dictator. I ask people to broaden their definition of socialism. Our ancestors were all socialists: You killed a deer and maybe you got the best cut, but you wouldn’t let it rot, you shared it. Similarly, I tell socialists, every society has a post office and none of them is efficient. No post office anywhere invented Federal Express.”

In 2006, Bruce Springsteen helped introduce Seeger to a new generation when he recorded We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions, an album of 13 songs popularized by Seeger. In 2009 Springsteen introduced Seeger at a concert to celebrate his 90th birthday: "He's gonna look a lot like your granddad that wears flannel shirts and funny hats. He's gonna look like your granddad if your granddad can kick your ass. At 90, he remains a stealth dagger through the heart of our country's illusions about itself."

Pete Seeger, aged 94, died on 27th January, 2014. President Barack Obama said in a statement. “He believed in the power of community - to stand up for what’s right, speak out against what’s wrong, and move this country closer to the America he knew we could be. Over the years, Pete used his voice - and his hammer - to strike blows for worker’s rights and civil rights; world peace and environmental conservation. And he always invited us to sing along. For reminding us where we come from and showing us where we need to go, we will always be grateful to Pete Seeger.”

Un-American Activities Committee in 1955.

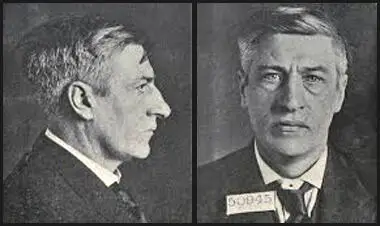

On this day in 1920 trade unionists James Larkin was found guilty and eceived a sentence of five to ten years in Sing Sing. Larkin's trial began on 30th January 1920. He decided to defend himself. He denied that he had advocated the overthrow of the Government. However, he admitted that he was part of the long American revolutionary tradition that included Abraham Lincoln, Walt Whitman, Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. He also quoted Wendell Phillips in his defence: "Government exists to protect the rights of minorities. The loved and the rich need no protection - they have many friends and few enemies."

In prison Larkin worked in the bootery, manufacturing and repairing shoes. Despite his inability to return to Ireland, he was annually re-elected as general secretary of the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union.

In November 1922, Alfred Smith won the election for Governor in New York. A few days later he ordered an investigation of the imprisonment of Larkin and on 17th January 1923 he granted him a free pardon. Larkin returned home to a triumphant reception. However, the new leader of the ITGWU, William O'Brien, was unwilling to step aside and managed to get Larkin expelled from the union in March 1924.

Larkin now established a new union, the Workers' Union of Ireland (WUI). He also became head of the Irish section of the Comintern and visited the Soviet Union in 1924. According to Bertram D. Wolfe he was not impressed with the communist system: "In 1924, the Moscow Soviet invited Larkin to come to its sessions as a representative of the people of Dublin, but he found nothing there to attract him, nor could they see their man in this wild-hearted rebel. I met him then, in the dining room of a Moscow hotel, where he was raising a series of scandals about the food, the service, and the obtuseness of waiters who could not understand plain English spoken with a thick Irish brogue... The Moscovites were glad when this eminent Dubliner returned to his native land."

Larkin successfully built up the WUI and in February 1932 won the North Dublin seat in the Dáil Éireann. However, he lost the seat in January 1933. Larkin was also forced to close down The Irish Worker. Later he started another radical newspaper, Irish Workers' Voice. He also served on the Dublin Trades Council, on the Port and Docks Board and the Dublin Corporation.

In the next election he won the North-East Dublin seat. However, in 1944 he was once again defeated at the polls. The following year his application to join the Irish Labour Party was finally accepted. James Larkin died in his sleep on 30th January, 1947. At his funeral Sean Casey said that Larkin had brought to the labour movement not only the loaf of bread but the flask of wine. Bertram D. Wolfe added: "James Larkin had outlived his time. He did not fit into the orderly, constructive, bureaucratized labour movement any more than he was suited to be a puppet of Moscow."

On this day in 1922 Len Shackleton was born in Bradford. As he pointed out in his autobiography, Crown Prince of Soccer: "Although there was no official football session at school, I spent all my spare time kicking a ball about in the school yard, in the fields near our home and even in the house, the latter with full parental approval. In the early 1930's, when television was merely a madman's mirage, when empty pockets put the cinema out of bounds, youngsters manufactured their own entertainment with a tennis ball."

Shackleton's parents could not afford to buy him football kit: "I could not afford real football boots so my Uncle John bought some studs and hammered them into an old pair of shoes. Uncle John always wanted me to be a footballer and he realized how much I would appreciate those studded shoes."

A teacher recognized Shackleton's talents and arranged for him to play in the North against the Midlands schoolboy game at York. He was only 4 feet 11 inches tall and was the smallest boy in the game. He was a great success and was selected to play for England Schoolboys in 1936. He scored two goals in England's 6-2 victory over Wales. He was also in the England team that beat Scotland (4-2) and Northern Ireland (8-3).

In August 1938 Shackleton was persuaded by George Allison to sign for Arsenal. As he pointed out in his autobiography, Crown Prince of Soccer: "With neighbours still gossiping outside, Mr Allison painted rosy Highbury pictures inside, with Dad, Mum, and "young Leonard" hanging on every word. He had no need to "sell" Arsenal to me. At that time, any 15-year-old boy, invited to join the greatest club in the world, would have been out of his mind to think twice. So it was that I accepted his offer of a job on the ground staff and signed as an amateur."

The Arsenal team at that time included players such as Ted Drake, Cliff Bastin, Eddie Hapgood, George Male, Reg Lewis, George Swindin, Bernard Joy, Alf Kirchen, Leslie Jones, George Hunt, Leslie Compton and Dennis Compton. However, he was loaned out to Enfield Town who played in the Athenian League.

Shackleton only played two non-league games for Arsenal before he was told by George Allison that he was not going to be offered a professional contract. "Mr Allison could not have been kinder: he handled that interview with diplomacy, repeatedly assuring me that he was advising me in my own interests, and told me not to take the news too badly. One day I would be grateful." Allison added: "Go back to Bradford and get a job. You will never make the grade as a professional footballer."

Shackleton found work at the London Paper Mills at Dartford. On the outbreak of the Second World War he returned to Bradford and after playing a couple of trial games Shackleton was signed by Bradford Park Avenue in August 1940. The Football League was suspended during the war but he made his debut in a friendly game against Leeds United on 25th December 1940.

Shackleton worked on aircraft wireless for GEC during the week. He volunteered for the Royal Air Force but was turned down because his war-work was considered too important. Later, he became a Bevin Boy and worked as a miner at Fryston Colliery near Castleford.

In October 1946 Stan Seymour, the manager of Newcastle United, signed Shackleton for a record fee of £13,000. While at Bradford Park Avenue he had scored 171 goals in 217 games. However, his unusual style of playing was not always appreciated and received a fair amount of barracking from the fans. When he was sold to Newcastle Stanley Matthews commented: "The £13,000 transfer of Len Shackleton from Bradford to Newcastle United is another proof of the harm unsporting spectators can do to players and clubs."

Shackleton made his debut for his new club against Newport County on 5th October. He scored six goals in the record 13-0 win. Jackie Milburn later commented: "On his debut against Newport County he scored six goals, a Division Two record, and put the last one in off his backside. Ever the showman, Shack always preferred to get applause for some daft trick rather than scoring a straight-forward goal."

It was hoped that Shackleton would help Newcastle United get promotion to the First Division. However, they only finished in 5th place with Shackleton scoring 19 goals in 32 league games. They did much better in the FA Cup and reached the semi-final where they were beaten by Charlton Athletic 4-0.

Shackleton developed a great partnership with Jackie Milburn. He later told his son: "Len Shackleton was a master craftsman and thanks to him I got among the goals. I clicked with him because I expected the unorthodox. If he ran one way, I ran the other, and sure enough the ball always found me. On the other hand, Len's quick-witted humour often caused me to laugh outright and lose control of the ball."

Not everyone appreciated the skills of Shackleton. His captain, Joe Harvey, argued that Shackleton was developing into a crowd entertainer rather than a team footballer and seemed more interested in beating four or five men than passing the ball to a better positioned team-mate. He added that "Newcastle would never win anything with him in the team". In February 1948 Newcastle United sold Shackleton to Sunderland in the First Division for the record fee of £20,050.

Shackleton won his first international cap for England against Denmark on 26th September, 1948. England drew the game 0-0. The England team that day included Stanley Matthews, Tommy Lawton, Laurie Scott, Jimmy Hagan, Billy Wright and Frank Swift.

Shackleton retained his place for the game against Wales but over the next six years he only played in three more games for his country. A journalist asked an England selector: "Why is Len Shackleton consistently left out of the England team?" The selector replied: "Because we play at Wembley Stadium, not the London Palladium".

Stanley Matthews argued in his autobiography, The Way It Was, that Shackleton was "unpredictable, brilliantly inconsistent, flamboyant, radical and mischievous; in short, he possessed all the attributes of a footballing genius which he undoubtedly was." Matthews claimed that he had a superb game against Germany in 1954 but it was the last time he played for England. As Matthews pointed out that his behaviour did "not go down well with the blazer brigade who ran English football and had such an important say in the selection of the England team."

Sunderland finished in 3rd place in the 1949-45 season. However, over the next few seasons the club went into decline and Shackleton failed to win any league or cup medals while he was at Roker Park. He also suffered from a serious ankle injury and was forced into retirement. He had scored 101 goals in 348 games for the club.

Shackleton worked as a football journalist with the Daily Express and the Sunday People. He also wrote a controversial autobiography, Crown Prince of Soccer (1955). Chapter 9 was entitled "The Average Director's Knowledge of Football". This was followed by a note from the publisher: "This chapter has deliberately been left blank in accordance with the author's wishes."

Len Shackleton died at Grange-over-Sands on 27th November 2000.

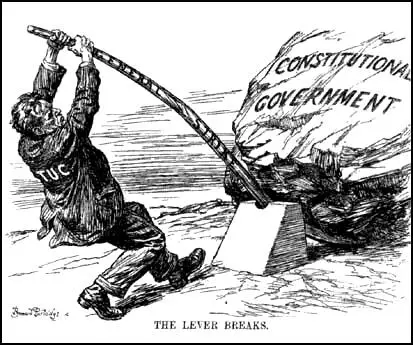

On this day in 1926 the General Strike begins. Arthur Pugh, the chairman of the TUC, was put in charge of the strike. John Hodge believed that Pugh was ambivalent about the dispute. "I have never heard him say that he was in favour of it, but I have never heard him say that he was against it." Hamilton Fyfe, the editor of the Daily Herald, was never convinced by him as a committed trade unionist and that given different circumstances "he would have made a fortune as a chartered accountant".

Paul Davies, went further and claimed that Pugh was a reluctant participant in this conflict: "Pugh confessed that the SIC had no policy with which to conduct negotiations. The SIC reluctance to prepare was based on a complex mixture of moderation, defeatism and realism, but above all fear: fear of losing, fear of winning, fear of bloodshed, fear of unleashing forces that union leaders could not control."

The Trade Union Congress adopted the following plan of action. To begin with they would bring out workers in the key industries - railwaymen, transport workers, dockers, printers, builders, iron and steel workers - a total of 3 million men (a fifth of the adult male population). Only later would other trade unionists, like the engineers and shipyard workers, be called out on strike. Ernest Bevin, the general secretary of the Transport & General Workers Union (TGWU), was placed in charge of organising the strike.

The TUC decided to publish its own newspaper, The British Worker, during the strike. Some trade unionists had doubts about the wisdom of not allowing the printing of newspapers. Workers on the Manchester Guardian sent a plea to the TUC asking that all "sane" newspapers be allowed to be printed. However, the TUC thought it would be impossible to discriminate along such lines. Permission to publish was sought by George Lansbury for Lansbury's Labour Weekly and H. N. Brailsford for the New Leader. The TUC owned Daily Herald also applied for permission to publish. Although all these papers could be relied upon to support the trade union case, permission was refused.

The government reacted by publishing The British Gazette. Baldwin gave permission to Winston Churchill to take control of this venture and his first act was commandeer the offices and presses of The Morning Post, a right-wing newspaper. The company's workers refused to cooperate and non-union staff had to be employed. Baldwin told a friend that he gave Churchill the job because "it will keep him busy, stop him doing worse things". He added he feared that Churchill would turn his supporters "into an army of Bolsheviks".

Churchill, along with Frederick Smith, Lord Birkenhead, were members of the government who saw the strike as "an enemy to be destroyed." Lord Beaverbrook described him as being full of the "old Gallipoli spirit" and in "one of his fits of vainglory and excessive excitement". Thomas Jones attempted to develop a plan that would bring the dispute to an end. Churchill was furious and said that the government should reject a negotiated settlement. Jones described Churchill as a "cataract of boiling eloquence" and told him that "we are at war" and the battle should continue until the government won.

John C. Davidson, the chairman of the Conservative Party, commented that Churchill was "the sort of man whom, if I wanted a mountain to be moved, I should send for at one. I think, however, that I should not consult him after he had moved the mountain if I wanted to know where to put it." Neville Chamberlain found Churchill's approach unacceptable and wrote in his diary that "some of us are going to make a concerted attack on Winston... he simply revels in this affair, which he will continually treat and talk of as if it were 1914."

Davidson, who had been put in overall charge of the government's media campaign, grew increasingly frustrated by Churchill's willingness to distort or suppress any item which might be vaguely favourable to "the enemy". Davidson argued that Churchill's behaviour became so extreme that he lost the support of the previously loyal Lord Birkenhead: "Winston, who had it firmly in his mind that anybody who was out of work was a Bolshevik; he was most extraordinary and never have I listened to such poppycock and rot."

Churchill called for the government to seize union funds. This was rejected and Churchill was condemned for his "wild ways". John Charmley has argued that "Churchill had a sentimentalist upper-class view of grateful workers co-operating with their betters for the good of the nation; he neither understood, nor realised that he did not understand, the Labour movement. To have written about the TUC leaders as though they were potential Lenins and Trotskys said more about the state of Churchill's imagination than it did about his judgment."

The government relied on volunteers to do the work of the strikers. Cass Canfield, worked in publishing until the strike began. "The British General Strike, which occurred in 1926, completely tied up the nation until the white-collar class went to work and restored some of the services. I remember watching gentlemen with Eton ties acting as porters in Waterloo Station; other volunteers drove railroad engines and ran buses. I was assigned to delivering newspapers and would report daily, before dawn, at the Horse Guards Parade in London. As time passed, the situation worsened; barbed wire appeared in Hyde Park, and big guns. Winston Churchill went down to the docks in an attempt to quell the rioting. For a couple of days there were no newspapers, and that was hardest of all to bear for no one knew what was going to happen next and everyone feared the outbreak of widespread violence. Finally, a single-sheet government handout appeared - the British Gazette - and people breathed easier, but settlement of the issues dividing labor and the government appeared to be insoluble."

However, most members of the Labour Party supported the strikers. This included Margaret Cole, who worked for the Fabian Research Department, pointed out: "Some members of the Labour Club formed a University Strike Committee, which set itself three main jobs; to act as liaison between Oxford and Eccleston Square, then the headquarters of the TUC and the Labour Party, to get out strike bulletins and propaganda leaflets for the local committees, and to spread them and knowledge of the issues through the University and the nearby villages."

In his book on the the General Strike, the historian Christopher Farman, studied the way the media dealt with this important industrial dispute. John C. Davidson, the Chairman of the Conservative Party, was given responsibility for the way the media should report the strike. "As soon as it became evident that newspaper production would be affected by the strike, Davidson arranged to bring the British Broadcasting Company under his effective control... no news was broadcast during the crisis until it had first been personality vetted by Davidson... Each of the five daily news bulletins plus a daily 'appreciation of the situation', which took the place of newspaper editorials, were drafted by Gladstone Murray in conjunction with Munro and then submitted to Davidson for his approval before being transmitted from the BBC's London station at Savoy Hill."

As part of the government propaganda campaign, the BBC reported that public transport was functioning again and after the first week of the strike it announced that most railmen had returned to work. This was in fact untrue as 97% of National Union of Railwaymen members remained on strike. It was true that volunteers were emerging from training and that more trains were in service. However, there was a sharp increase in accidents and several passengers were killed during the strike. Unskilled volunteers were also accused of causing thousands of pounds' worth of damage.

Several politicians representing the Conservative Party and the Liberal Party, appeared on BBC radio and made vicious attacks on the trade union movement. William Graham, the Labour Party MP for Edinburgh Central, wrote to John Reith, the BBC's managing director, suggesting that he should allow "a representative Labour or Trade Union leader to state the case for the miners and other workers in this crisis".

Ramsay MacDonald, the leader of the Labour Party, also contacted Reith and asked for permission to broadcast his views. Reith recorded in his diary: "He (MacDonald) said he was anxious to give a talk. He sent a manuscript along... with a friendly note offering to make any alterations which I wanted... I sent it at once to Davidson for him to ask the Prime Minister, strongly recommending that he should allow it to be done." The idea was rejected and Reith argued: "I do not think that they treat me altogether fairly. They will not say we are to a certain extent controlled and they make me take the onus of turning people down. They are quite against MacDonald broadcasting, but I am certain it would have done no harm to the Government. Of course it puts me in a very awkward and unfair position. I imagine it comes chiefly from the PM's difficulties with the Winston lot."

When he heard the news, MacDonald, wrote Reith an angry letter, calling "for an opportunity for the fair-minded and reasonable public to hear Labour's point of view". Anne Perkins, the author of A Very British Strike: 3 May-12 May 1926 (2007) has argued that if the government had accepted the proposal and people had "heard an Opposition voice would certainly have done something to restore the faith of millions of working-class people who had lost confidence in the BBC's potential to be a national institution and a reliable and trustworthy source of news."

At the same time Stanley Baldwin was allowed to make several broadcasts on the BBC. Baldwin "had recognized the importance of the new medium from its inception... now, with an expert blend of friendliness and firmness, he repeated that the strike had first to be called off before negotiations could resume, but repudiated the suggestion that the Government was fighting to lower the standard of living of the miners or of any other section of the workers".

In one broadcast Baldwin argued: "A solution is within the grasp of the nation the instant that the trade union leaders are willing to abandon the General Strike. I am a man of peace. I am longing and working for peace, but I will not surrender the safety and security of the British Constitution. You placed me in power eighteen months ago by the largest majority accorded to any party for many years. Have I done anything to forfeit that confidence? Cannot you trust me to ensure a square deal, to secure even justice between man and man?"

By 12th May, 1926, most of the daily newspapers had resumed publication. The Daily Express reported that the "strike had a broken back" and it would be all over by the end of the week. Harold Harmsworth, Lord Rothermere, was extremely hostile to the strike and all his newspapers reflected this view. The Daily Mirror stated that the "workers have been led to take part in this attempt to stab the nation in the back by a subtle appeal to the motives of idealism in them." The Daily Mail claimed that the strike was one of "the worst forms of human tyranny".

Walter Citrine, the general secretary of the Trade Union Congress (TUC), was desperate to bring an end to the General Strike. He argued that it was important to reopen negotiations with the government. His view was "the logical thing is to make the best conditions while our members are solid". Baldwin refused to talk to the TUC while the General Strike persisted. Citrine therefore contacted Jimmy Thomas, the general secretary of the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR), who shared this view of the strike, and asked him to arrange a meeting with Herbert Samuel, the Chairman of the Royal Commission on the Coal Industry.

Without telling the miners, the TUC negotiating committee met Samuel on 7th May and they worked out a set of proposals to end the General Strike. These included: (i) a National Wages Board with an independent chairman; (ii) a minimum wage for all colliery workers; (iii) workers displaced by pit closures to be given alternative employment; (iv) the wages subsidy to be renewed while negotiations continued. However, Samuel warned that subsequent negotiations would probably mean a reduction in wages. These terms were accepted by the TUC negotiating committee, but were rejected by the executive of the Miners' Federation.

Herbert Smith was furious with the TUC for going behind the miners back. One of those involved in the negotiations, John Bromley of the NUR, commented: "By God, we are all in this now and I want to say to the miners, in a brotherly comradely spirit... this is not a miners' fight now. I am willing to fight right along with them and suffer as a consequence, but I am not going to be strangled by my friends." Smith replied: "I am going to speak as straight as Bromley. If he wants to get out of this fight, well I am not stopping him."

Walter Citrine wrote in his diary: "Miner after miner got up and, speaking with intensity of feeling, affirmed that the miners could not go back to work on a reduction in wages. Was all this sacrifice to be in vain?" Citrine quoted Cook as saying: "Gentleman, I know the sacrifice you have made. You do not want to bring the miners down. Gentlemen, don't do it. You want your recommendations to be a common policy with us, but that is a hard thing to do."

Herbert Smith asked Arthur Pugh if the decision was "the unanimous decision of your Committee?" Pugh replied that it was the view that the General Strike should come to an end. Smith pleaded for further negotiations. However, Pugh was insistent: "That is it. That is the final decision, and that is what you have to consider as far as you are concerned, and accept it."

On the 11th May, at a meeting of the Trade Union Congress General Committee, it was decided to accept the terms proposed by Herbert Samuel and to call off the General Strike. The following day, the TUC General Council visited 10 Downing Street and attempted to persuade the Government to support the Samuel proposals and to offer a guarantee that there would be no victimization of strikers.

Baldwin refused but did say if the miners returned to work on the current conditions he would provide a subsidy for six weeks and then there would be the pay cuts that the Mine Owners Association wanted to impose. He did say that he would legislate for the amalgamation of pits, introduce a welfare levy on profits and introduce a national wages board. The TUC negotiators agreed to this deal. As Lord Birkenhead, a member of the Government was to write later, the TUC's surrender was "so humiliating that some instinctive breeding made one unwilling even to look at them."

Baldwin already knew that the Mine Owners Association would not agree to the proposed legislation. They had already told Baldwin that he must not meddle in the coal industry. It would be "impossible to continue the conduct of the industry under private enterprise unless it is accorded the same freedom from political interference that is enjoyed by other industries."

To many trade unionists, Walter Citrine had betrayed the miners. A major factor in this was money. Strike pay was haemorrhaging union funds. Information had been leaked to the TUC leaders that there were cabinet plans originating with Winston Churchill to introduce two potentially devastating pieces of legislation. "The first would stop all trade union funds immediately. The second would outlaw sympathy strikes. These proposals would... make it impossible for the trade unions' own legally held and legally raised funds to be used for strike pay, a powerful weapon to drive trade unionists back to work."

Arthur Pugh, the President of the Trade Union Congress, and Jimmy Thomas, the general secretary of the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR), informed the Miners' Federation of Great Britain leaders, that if the General Strike was terminated the government would instruct the owners to withdraw their notices, allowing the miners to return to work on the "status quo" while the wage reductions and reorganisation machinery were negotiated. A. J. Cook asked what guarantees the TUC had that the government would introduce the promised legislation, Thomas replied: "You may not trust my word, but will not accept the word of a British gentleman who has been Governor of Palestine".

Jennie Lee, was a student at Edinburgh University when her father, a miner in Lochgelly in Scotland. During the lock-out she returned to help her family. "Until the June examinations were over I was chained to my books, but I worked with a darkness around me. What was happening in the coalfield? How were they managing? Once I was free to go home to Lochgelly my spirits rose. When you are in the thick of a fight there is a certain exhilaration that keeps you going."

When the General Strike was terminated, the miners were left to fight alone. Cook appealed to the public to support them in the struggle against the Mine Owners Association: "We still continue, believing that the whole rank and file will help us all they can. We appeal for financial help wherever possible, and that comrades will still refuse to handle coal so that we may yet secure victory for the miners' wives and children who will live to thank the rank and file of the unions of Great Britain."

On 21st June 1926, the British Government introduced a Bill into the House of Commons that suspended the miners' Seven Hours Act for five years - thus permitting a return to an 8 hour day for miners. In July the mine-owners announced new terms of employment for miners based on the 8 hour day. As Anne Perkins has pointed out this move "destroyed any notion of an impartial government".

A. J. Cook toured the coalfields making passionate speeches in order to keep the strike going: "I put my faith to the women of these coalfields. I cannot pay them too high a tribute. They are canvassing from door to door in the villages where some of the men had signed on. The police take the blacklegs to the pits, but the women bring them home. The women shame these men out of scabbing. The women of Notts and Derby have broken the coal owners. Every worker owes them a debt of fraternal gratitude."

Hardship forced men to begin to drift back to the mines. By the end of August, 80,000 miners were back, an estimated ten per cent of the workforce. 60,000 of those men were in two areas, Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire. "Cook set up a special headquarters there and rushed from meeting to meeting. He was like a beaver desperately trying to dam the flood. When he spoke, in, say, Hucknall, thousands of miners who had gone back to work would openly pledge to rejoin the strike. They would do so, perhaps for two or three days, and then, bowed down by shame and hunger, would drift back to work."

Herbert Smith and Arthur Cook had a meeting with government representatives on 26th August, 1926. By this stage Cook was willing to do a deal with the government than Smith. Cook asked Winston Churchill: "Do you agree that an honourably negotiated settlement is far better than a termination of struggle by victory or defeat by one side? Is there no hope that now even at this stage the government could get the two sides together so that we could negotiate a national agreement and see first whether there are not some points of agreement rather than getting right up against our disagreements." According to Beatrice Webb "if it were not for the mule-like obstinacy of Herbert Smith, A. J. Cook would settle on any terms."

This meeting revealed the differences between Smith and Cook. "After a wary start the two seem to have developed a mutual respect during their many hours of shared stress. By the middle of the lock-out, however, they seem to have drifted on to different. wavelengths. Undoubtedly Cook felt Smith's obstinacy to be impractical and damaging. Smith, however, as MFGB President, was the Federation's chief spokesman, and Cook could not officially or openly dissociate himself from Smith's position. The MFGB special conference had granted the officials unfettered negotiating power, but Smith seems to have grown more stubborn as the miners' bargaining position worsened. One may admire his spirit, but not his wisdom. It is likely that by this time Smith reflected a minority view within the Federation Executive, but as President his position was unchallengeable, and there was no public dissent at his inflexibility. Cook, meanwhile, had embraced a conciliatory, face-saving position: he was only too aware of the drift back to work in some areas; he saw the deteriorating condition of many miners and their families."

In October 1926 hardship forced men to begin to drift back to the mines. By the end of November most miners had reported back to work. Will Paynter remained loyal to the strike although he knew they had no chance of winning. "The miners' lock-out dragged on through the months of 1926 and really was petering-out when the decision came to end it. We had fought on alone but in the end we had to accept defeat spelt out in further wage-cuts."

As one historian pointed out: "Many miners found they had no jobs to return to as many coal-owners used the eight-hour day to reduce their labour force while maintaining productions levels. Victimisation was practised widely. Militants were often purged from payrolls. Blacklists were drawn up and circulated among employers; many energetic trade unionists never worked in a pit again after 1926. Following months of existence on meague lockout payments and charity, many miners' families were sucked by unemployment, short-term working, debts and low wages into abject poverty."

At the end of the strike some people were highly critical of the way the government had used its control of the media to spread false news. This included an attack on the The British Gazette. One journalist wrote: "One of the worst outrages which the country had to endure - and to pay for - in the course of the strike, was the publication of the British Gazette. This organ, throughout the seven days of its existence, was a disgrace alike to the British Government and to British journalism."

The vast majority of newspapers supported the government during the dispute. This was especially true of the newspapers owned by Lord Rothermere. The Daily Mail suggested that "the country has come through deep waters and it has come through in triumph, setting such an example to the world as has not been seen since the immortal hours of the War. It has fought and defeated the worst forms of human tyranny. This is a moment when we can lift up our head and our hearts." The Daily Mirror compared the strikers to a foreign enemy: "The unconquerable spirit of our people has been aroused again in self-defence - as it was against the foreign foe in 1914." The Times took a similar line arguing that the General Strike was "a fundamental struggle between right and wrong... victory was won... by the splendid courage and self-sacrifice of the nation itself."

The Manchester Guardian disagreed and condemned the right-wing press for comparing strikers to a foreign enemy and urging the government to "teach the workmen the lesson they deserve". The newspaper reminded those editors like Thomas Marlowe, that many of these men had a few years earlier been praised for bravery during the First World War. It added the "comradeship" developed during the war "was a big factor in the unparalleled pacific character of this great conflict".

John Reith, the BBC's managing director, was concerned about the way the government had controlled what it was able to broadcast. In a confidential letter sent to senior BBC staff, Reith wrote. "The attitude of the BBC during the crisis caused pain and indignation to many subscribers. I travelled by car over two thousand miles during the strike and addressed very many meetings. Everywhere the complaints were bitter that a national service subscribed to by every class should have given only one side during the dispute. Personally, I feel like asking the Postmaster-General for my licence fee back."

In 1927 the British Government passed the Trade Disputes and Trade Union Act. This act made all sympathetic strikes illegal, ensured the trade union members had to voluntarily 'contract in' to pay the political levy to the Labour Party, forbade Civil Service unions to affiliate to the TUC, and made mass picketing illegal. As A. J. P. Taylor has pointed out: "The attack on Labour party finance came ill from the Conservatives who depended on secret donations from rich men."

The legislation defined all sympathetic strikes as illegal, confining the right to strike to "the trade or industry in which the strikers are engaged". The funds of any union engaging in an illegal strike was liable in respect of civil damages. It also limited the right to picket, in terms so vague that almost any form of picketing might be liable to prosecution. As Julian Symons has pointed out: "More than any other single measure, the Trade Disputes Act caused hatred of Baldwin and his Government among organized trade unionists."

One of the results of this legislation was that trade union membership fell below the 5,000,000 mark for the first time since 1926. However, despite its victory over the trade union movement, the public turned against the Conservative Party. Over the next three years the Labour Party won all the thirteen by-elections that took place. In the 1929 General Election Labour won 287 seats and its leader, Ramsay MacDonald, formed the next government.

On this day in 1939 Joseph Stalin dismissed Maxim Litvinov, his Jewish Commissar for Foreign Affairs, to please Adolf Hitler, just before the signing of the Nazi-Soviet Pact.

After the October Revolution, Litvinov was appointed by Vladimir Lenin as the Soviet Government's representative in Britain. However, in 1918, Litvinov was arrested by the British Government and held until exchanged for Bruce Lockhart, the British diplomat who had been imprisoned in Russia. As he explained in his autobiography: "After the October Revolution I was appointed the first ambassador to England. Ten months later I was arrested as a hostage for Lockhart and we were later exchanged. I travelled to Sweden and Denmark for negotiations with the bourgeois governments and concluded a series of agreements on the exchange of prisoners of war. I achieved the removal of the British blockade, made the first trade deals in Europe and dispatched the first cargoes after the blockade had been lifted."

In the summer of 1921, Carr Van Anda, the managing director of the New York Times, sent Walter Duranty to report on the new policy of war communism in Russia. At first, Maxim Litvinov, refused to let him into the country because of his previous hostile stories about the government. George Seldes, of the Chicago Tribune, said that nobody expected Duranty to get a visa. "Litvinov singled Walter Duranty out - he didn't want to admit him."

However, Litvinov changed his mind and did issue him with a visa after he read an article by Duranty that appeared in the New York Times on 13th August, 1921: "Lenin has thrown communism overboard. His signature appears in the official press of Moscow in August 9, abandoning State ownership, with the exception of a definite number of great industries of national importance - such as were controlled by the State in France, England and Germany during the war - and re-establishing payment by individuals for railroads, postal and other public services." However, like the other Western journalists, he was still not allowed into the famine areas.

Litvinov also had problems with Floyd Gibbons, another American journalist who wanted to report the famine. David Randall, the author of The Great Reporters (2005) has argued: "Some time that summer, word began to leak out of the new Soviet state that people in their millions were starving in the Volga region. Checking these rumours was easier said than done. The Bolshevik government allowed no Western journalists to be based in Moscow, and coverage of the country was in the hands of reporters who hung around Riga's restaurants talking to emigres, White Russians and other unreliable witnesses.... The Soviets were not letting them in; they wanted US food aid, but were afraid the full extent of the tragedy would be revealed. After the Tribune's men kicked their heels for a week, Chicago cabled Floyd Gibbons to go to Riga himself..... The rest of the press had dutifully filled out an application form for entry. Not Gibbons. Instead he told his German pilot to keep his plane primed for take-off, and let it be known around the bars that lie was thinking of making an illicit flight into Russia. Sure enough, informants picked up the story, and next day Gibbons was summoned to see Litvinov, the Soviet ambassador. The meeting pitted the two wiliest brains in Riga against each other. Litvinov said he knew about Gibbons's plane, and warned him that if he tried to fly across the border he would be shot down. Gibbons countered by pointing out that the Russian border ran from the Baltic to the Black Sea, and anti-aircraft guns covered a mere traction of it. Litvinov then threatened to have Gibbons arrested, to which the reporter replied that the Soviets had just released all their US prisoners in order to secure food aid and were not likely to start incarcerating Americans again. Checkmate. That night, while the rest of the press fumed in Riga, Gibbons boarded a train for Moscow with Litvinov, and, after a few days in the capital, was on another train bound for the Volga."

Walter Duranty said that Floyd Gibbons "fully deserved his success because he had accomplished the feat of bluffing the redoubtable Litvinov stone-cold... a noble piece of work." Over the next few days Gibbons was the only reporter to document the horrifying prospect of the deaths of as many as fifteen million people from starvation.

Litvinov was then employed as the Soviet Government's roaming ambassador. It was largely through his efforts that Britain agreed to end its economic blockade of the Soviet Union. Litvinov also negotiated several trade agreements with European countries. In 1930 Joseph Stalin appointed Litvinov as Commissar of Foreign Affairs. A firm believer in collective security, Litvinov worked very hard to form a closer relationships with France and Britain.

With the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt to the presidency, the diplomatic recognition of the Soviet Union became a strong possibility. In November 1933 the Soviets were invited to send a representative to Washington to begin negotiations. Walter Duranty, an American journalist based in Moscow, obtained permission to accompany Litvinov on his historic journey across the Atlantic. When they reached New York Duranty quoted Litvinov as describing the skyline as "looming like castle giants in the hazy morning".

As Jean Edward Smith pointed out in FDR (2007): "The ostensible outstanding issues involved freedom of religion for Americans in Russia and the continued agitation for world revolution mounted by the Comintern. The real sticking point was restitution of American property seized by the Soviet government in its nationalization decree of 1919. Roosevelt and Litvinov compromised. The agreement is known as the Litvinov Assignment. The Soviet government assigned to the United States its claim to all Russian property in the United States that antedated the Revolution. The United States agreed to seize the property on behalf of the Soviet Union, thus giving effect to the Soviet nationalization decree, and use the proceeds to pay the claims of Americans whose property in Russia had been confiscated.... Shortly after midnight on the morning of November 17, FDR and Litvinov signed the documents restoring diplomatic relations." Walter Duranty wrote in the New York Times on 18th November 1933 that he had just witnessed "the ten days that steadied the world".