Spartacus Blog

Winston Churchill should not have been voted as the Greatest Briton in history.

In 2002 BBC television carried out a poll to discover whom the United Kingdom public considered the 100 Greatest Britons in history. The BBC series included individual programmes featuring the top ten, with viewers having further opportunity to vote after each programme. Winston Churchill was voted as number one. This result was slightly undermined by the fact that Princess Diana came third. (1)

We were told that the reason for this decision was that Churchill was the prime minister during the Second World War (as I intend to show it definitely was not because of his early political career). However, this seems strange as it does not explain why in the 1945 General Election, when the British people had the opportunity to show their gratitude for his role in winning the war, he suffered a humiliating defeat and Clement Attlee became the new prime minister. It was a high turnout with 72.8% of the electorate voting. With almost 12 million votes, Labour had 47.8% of the vote to 39.8% for the Conservatives. Labour made 179 gains from the Tories, winning 393 seats to 213. The 12.0% national swing from the Conservatives to Labour, remains the largest ever achieved in a British general election. (2)

Churchill's previous Epping seat had been split into two. Churchill chose the more residential and Conservative half that had been renamed Woodford. Out of respect for Churchill, the other main political parties decided not to contest the seat. The only person willing to stand against him was Alexander Hancock, a local farmer who described himself as a "philosophical Communist," who advocated that people should only work one day a week. The strength of feeling against Churchill was sufficient to give his solitary opponent 10,488 votes against his disappointing 27,688. (3)

Clive Ponting, the author of Winston Churchill (1994) has pointed out: "Despite the fact that Churchill had been so confident about the public's gratitude, he had led the Conservatives to their greatest ever defeat under universal suffrage, and the Labour Party, which he hated so much, and abused so vehemently, became a majority Government for the first time in its history." (4)

Churchill had his own ideas why he had been defeated. He told his fellow Tory MP, Duff Cooper: "There are some unpleasant features in this election which indicate the rise of bad elements. Conscientious objectors were preferred to candidates of real military achievement and service. All the Members of Parliament who had done most to hamper and obstruct the war were returned by enormously increased majorities. None of the values of the years before were preserved... The soldiers voted with mirthful irresponsibility... Also, there is the latent antagonism of the rank and file for the officer class." (5)

Sarah Churchill believed that her father's attack on socialism had backfired: "Socialism as practiced in the war, did no one any harm and quite a lot of people good. The children of this country have never been so well fed or healthy, what milk there was, was shared equally, the rich didn't die because their meat ration was no larger than the poor; and there is no doubt that this common sharing and feeling of sacrifice was one of the strongest bonds that unified us. So why, they say, cannot this common feeling of sacrifice be made to work as effectively in peace?" (6)

Winston Churchill: Historians and the Conservative Media

In 2004, the University of Leeds and Ipsos MORI conducted an online survey of 258 academics who specialised in 20th-century British history and/or politics. There were 139 replies to the survey, a return rate of 54% - by far the most extensive survey done so far on this subject. The respondents were asked, among other historical questions, to rate all the 20th-century prime ministers in terms of their success and asking them to assess the key characteristics of successful PMs. Respondents were asked to indicate on a scale of 0 to 10 how successful or unsuccessful they considered each PM to have been in office (with 0 being highly unsuccessful and 10 highly successful). A mean of the scores could then be calculated and a league table based on the mean scores. The five Labour prime ministers were, on average, judged to have been the most successful, with a mean of 6.0 (median of 5.9). The three Liberal PMs averaged 5.8 (median of 6.2) and the twelve Conservative PMs 4.8 (median of 4.1). Top of the list came Clement Attlee with a score of 8.3, a man who does not feature in the BBC top 100. (7)

Why did the British public felt very differently about Winston Churchill in 2002 than they did in 1945? The short answer is that in 1945 they expressed their opinion based on their experience of his political career. In 2002 people were relying on the image presented of Churchill by a Conservative media. This also helps explain why the academics rated Labour prime ministers so much higher than the general public. Using the Conservative dominated newspapers, Margaret Thatcher was very successful at promoting Churchill's reputation by linking herself with this former prime minister. Tim Bell, an adman with Saatchi and Saatchi, and Sir Gordon Reece, a television producer who had become head of communications at Conservative Central Office, "set about turning Margaret Thatcher from a shrill, plumpish Tory matron to a cross between Winston Churchill and Mrs Miniver." (8)

The reason the British public chose Clement Attlee over Winston Churchill was that they had knowledge of his political career before the start of the Second World War. It is claimed that by 1929 Churchill was the most hated politician in Britain. His reputation was so toxic that Conservative prime ministers in the 1930s, Stanley Baldwin and Neville Chamberlain, would not have him in their governments. In fact, Churchill was considered to be the main reason why the Conservative Party lost the 1929 General Election as "he was widely blamed for the poor state of the economy and the Government's political fortunes". (9)

Early Political Career

Churchill was initially elected to the House of Commons as a Conservative in the 1900 General Election. However, by March 1904 he came to the conclusion that he would have a much better political future if he joined the Liberal Party. Randolph S. Churchill, the author of Winston Churchill (1967) pointed out: "He (Churchill) entered the Chamber of the House of Commons, stood for a moment at the Bar, looked briefly at both the Government and Opposition benches and strode swiftly up the aisle. He bowed to the Speaker and turned sharply to his right to the Liberal benches." (10) In protest, all the Conservative Party MPs walked out of the chamber. (11)

Churchill was right and the Liberals had a landslide victory in the 1906 General Election. He was appointed as President of the Board of Trade, and at the age of 33, he was the youngest Cabinet member since 1866. Churchill identified with the left-wing of the party and when the House of Lords blocked the government's progressive legislation he became the "attack dog" against the Conservatives. He argued that "the time has come for the total abolition of the House of Lords" and described the former Foreign Secretary, Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, 5th Marquess of Lansdowne, as "the representative of a played out, obsolete, anachronistic Assembly, a survival of a feudal arrangement utterly passed out of its original meaning, a force long since passed away, which only now requires a smashing blow from the electors to finish it off for ever." (12)

However, he was to lose his liberal image during his period as Home Secretary. Churchill upset the trade union movement during the Newport Docks strike in May 1910. With the dockers on strike, the owners wanted to bring in outside labour to break the strike and the local magistrates, alarmed at the possibility of mass disorder, asked the Home Office to provide troops or police to protect the blacklegs. Churchill was on holiday and Richard Haldane, who was in charge at the time, refused. Churchill quickly returned to London and authorised the use of 250 Metropolitan police, with 300 troops in reserve, to support the owners and protect the outside labour they brought in. (13)

Six months later Churchill was faced with another dispute in South Wales, this time in the Rhondda valley where a lock-out and strike following a conflict over pay rates for a difficult new seam led to a bitter ten-month strike. Once again Churchill was asked to send troops after strikers rioted. At first Churchill called for arbitration. The following day he was attacked by Conservative newspapers, particularly by The Times, that declared that if "loss of life" occurred as a result of the riots, "the responsibility will lie with the Home Secretary." (14)

On 8th November, 1910, Churchill sent in the cavalry and went on patrol in Tonypandy and the neighbouring valleys. He also deployed 900 Metropolitan police and 1,500 officers from other forces to support two squadrons of hussars and two infantry companies stationed in the area. James Keir Hardie, the leader of the Labour Party, protested against the "impropriety" of sending in troops and the "harsh methods" being used. Churchill told King George V that the "owners are very unreasonable" and "both sides are fighting one another regardless of human interests or the public welfare." However, the troops, remained in the area for eleven months, supporting the police, and were at times deployed on the streets with fixed bayonets. (15)

Churchill became convinced that German money was funding a dock and rail strike over union recognition in Liverpool and on the 14th August 1911 he sent in the army who opened fire on strikers. It is estimated that about 50,000 soldiers arrived in the city. "His attitude was openly partisan; in every case of a protest about police or military violence he simply accepted the official account and dismissed the version from the strikers." David Lloyd George intervened and persuaded the employers to settle the dispute. When he heard the news he immediately telephoned Lloyd George to complain as he wanted an open conflict followed by a clear defeat for the unions. (16)

Winston Churchill also upset the radical wing of the Liberal Party by his attitude towards votes for women and was a strong opponent of the Conciliation Bill that was designed to conciliate the suffragist movement by giving a limited number of women the vote, according to their property holdings and marital status. As a young man he argued: "I shall unswervingly oppose this ridiculous movement (to give women the vote)... Once you give votes to the vast numbers of women who form the majority of the community, all power passes to their hands." His wife, Clementine Churchill, was a supporter of votes for women and after marriage he did become more sympathetic but was not convinced that women needed the vote. When a reference was made at a dinner party to the action of certain suffragettes in chaining themselves to railings and swearing to stay there until they got the vote, Churchill's reply was: "I might as well chain myself to St Thomas's Hospital and say I would not move till I had had a baby." However, it was the policy of the Liberal Party to give women the vote and so he could not express these opinions in public. (17)

First Lord of the Admiralty

Winston Churchill was extremely proud of the British Empire but he was very concerned about its future. Superficially the empire seemed the strongest power in the world. However, he was aware that it was in trouble. This vast, sprawling Empire was not integrated politically, economically or strategically and was a drain on Britain's very limited resources. An island of some forty million people with an economy that was being rapidly overtaken by other powers such as the United States and Germany. It has been argued that during this period "Churchill came up against the fundamental factor that was to shape all his political life - Britain's position as a great power was declining." (18)

Reginald McKenna, First Lord of the Admiralty, became involved in an arms race with German Navy. In 1909 authorized an additional four dreadnoughts, hoping that Germany would be willing to negotiate a treaty about battleship numbers. If this did not happen, an additional four ships would be built. In 1910, the British eight-ship construction plan went ahead, including four Orion-class super-dreadnoughts. Germany responded by building three warships, giving the United Kingdom a superiority of 22 ships to 13. Negotiations began between the two countries but talks foundered on the question on whether British Commonwealth battlecruisers should be included in the count. (19)

David Lloyd George complained bitterly to H. H. Asquith about the demands being made by Reginald McKenna to spend more money on the navy. He reminded Asquith of "the emphatic pledges given by us before and during the general election campaign to reduce the gigantic expenditure on armaments built up by our predecessors... but if Tory extravagance on armaments is seen to be exceeded, Liberals... will hardly think it worth their while to make any effort to keep in office a Liberal ministry... the Admiralty's proposals were a poor compromise between two scares - fear of the German navy abroad and fear of the Radical majority at home... You alone can save us from the prospect of squalid and sterile destruction." (20)

Lloyd George was constantly in conflict with McKenna and suggested that Winston Churchill, should become First Lord of the Admiralty. H. H. Asquith took this advice and Churchill was appointed to the post on 24th October, 1911. McKenna, with the greatest reluctance, replaced him at the Home Office. He was now in charge of the greatest naval establishment in the world, "with its fleet patrolling the seven seas, and its training schools and dockyards and warehouses and harbours forming a service that embodied British might." (21)

Churchill's appointment worried the press: "The Conservative journals, invariably pro-Navy had little faith in Churchill's appointment, fearful that his rhetorical style and changeable moods, as they saw it, were unsuitable to that pre-eminent administrative post." (22) Some of Britain's newspapers questioned his appointment. For example, the Sunday Observer commented: "We cannot detect in his career any principles or even any consistent outlook upon public affairs. His ear is always on the ground; he is the true demagogue, sworn to give the people what they want, or rather, and that is infinitely worse, what he fancies they want. No doubt he will give the people an adequate Navy if they insist upon it." (23)

The Spectator claimed that Churchill "has not the loyalty, the dignity, the steadfastness to make an efficient head of a great office." However, he gained the support of the Conservative press when he made a speech on 9th November, 1911, making it clear that Britain would retain her existing margin of superiority over the German Navy even if the Germans stepped up their rate of building. This brought him plaudits from old enemies like Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe, whose newspapers, The Daily Mail, The Times, The Daily Mirror and The Evening News, had constantly attacked the Liberal government, told Churchill: "I judge public men on their public face and I believe that your inquiring, industrious mind is alive to the national danger." (105) Churchill's speech upset radicals such as Wilfred Scawen Blunt who sorrowfully concluded that he was "bitten with Grey's anti-German policy." (24)

One of Churchill's first decisions was to set up the Royal Naval Air Service. He also established an Air Department at the Admiralty so as to make full use of this new technology. Churchill was so enthusiastic about these new developments that he took flying lessons. The Army envisaged its air service as primarily one of reconnaissance, avoiding, wherever possible, any actual air battles. "Churchill wanted the Navy to use aircraft more aggressively; both bomb-dropping and machine-gunnery became part of the experimentation and training of the Royal Naval Air Service." (25)

On 7th February, 1912, Churchill made a speech where he pledged naval supremacy over Germany "whatever the cost". Churchill, who had opposed naval estimates of £35 million in 1908, now proposed to increase them to over £45 million. In 1914 Churchill advocated spending £51,550,000 on the Navy. The "new ruler of the King's navy demanded an expenditure on new battleships which made McKenna's claims seem modest". (26) Lloyd George remained opposed to what he saw as inflated naval estimates and was not "prepared to squander money on building gigantic flotillas to encounter mythical armadas". According to George Riddell, a close friend of both men, recorded they were drifting wide apart on principles". (27) Riddell reported there were even rumours that Churchill was "mediating... going over to the other side." (28)

First World War

At a Cabinet meeting on Friday, 31st July, 1914, more than half the Cabinet, including David Lloyd George, Charles Trevelyan, John Burns, John Morley, John Simon and Charles Hobhouse, were bitterly opposed to Britain entering the war. Only two ministers, Winston Churchill and Sir Edward Grey, argued in favour and H. H. Asquith appeared to support them. At this point, Churchill suggested that it might be possible to continue if some senior members of the Conservative Party could be persuaded to form a Coalition government. (29)

Churchill wrote to Lloyd George after the Cabinet meeting: "I am most profoundly anxious that our long co-operation may not be severed... I implore you to come and bring your mighty aid to the discharge of our duty. Afterwards, by participating, we can regulate the settlement." He warned that if Lloyd George did not change his mind: "All the rest of our lives we shall be opposed. I am deeply attached to you and have followed your instructions and guidance for nearly 10 years." (30)

On 2nd August another Cabinet meeting took place. Marvin Rintala, the author of Lloyd George and Churchill: How Friendship Changed Politics (1995) points out: "A major change had clearly taken place within the cabinet. That change centred on Lloyd George. According to Asquith, on the morning of 2 August, Lloyd George was still against any kind of British intervention in any event ... Throughout that long Sunday he had contemplated retiring to North Wales if Britain went to war. It appears that until 3 August he intended to resign from the Cabinet upon any British declaration of war ... In fact, Lloyd George was first firmly against war, and then equally firmly for war." (31)

Lloyd George's change of mind shocked government ministers. John Burns immediately resigned as he now knew war was inevitable. Charles Trevelyan, John Morley and John Simon also handed in letters of resignation with "at least another half-dozen waited upon the effective hour". (32) According to the historian, A. J. P. Taylor: "At 10.30 p.m. on 4th August 1914 the king held a privy council at Buckingham Palace, which was attended only by one minister and two court officials. The council sanctioned the proclamation of a state of war with Germany from 11 p.m. That was all. The cabinet played no part once it had resolved to defend the neutrality of Belgium. It did not consider the ultimatum to Germany, which Sir Edward Grey, the foreign secretary, sent after consulting only the prime minister, Asquith, and perhaps not even him." (33)

The First World War turned out to be a disaster for Churchill's political career. By 28th September, 1914, Antwerp was under siege. King Albert I and his Belgian government were based in the city. There was also 145,000 trained Belgian troops, within its fortified perimeter. On 1st October, H. H. Asquith wrote to Venetia Stanley about the situation in Antwerp that "its fall would be a great moral blow to the allies" but added "of course it would be idle butchery to send" British soldiers to defend the city. (34)

Churchill ignored Asquith's views and gained permission from Lord Kitchener, Secretary of State for War, to go to organise the defence of Antwerp. He took with him 2,000 men of the Royal Marine Brigade to support those who were already in Antwerp. On 5th October he sent a message to Asquith, where he offered to resign his office and "undertake command of relieving and defensive forces assigned to Antwerp in conjunction with Belgian Army, provided that I am given necessary military rank and authority, and full powers of a commander of a detached force in the field. I feel it my duty to offer my services because I am sure this arrangement will afford the best prospects of a victorious result to an enterprise in which I am deeply involved." (35) The message has been described as "surely one of the most extraordinary communications ever made by a British Cabinet Minister to his leader". (36)

Lord Kitchener was prepared to agree to his request and make him a Lieutenant-General but Asquith over-ruled him and Churchill was ordered back to Britain. Ted Morgan, the author of Winston Churchill (1983) has argued that Churchill's decision to try and hold Antwerp was wrong: "Holding Antwerp was an article of faith for Churchill. Imbued as he was with a sense of historical precedent, he must have remembered that during the Napoleonic Wars, the British had landed on Walcheren Island, only thirty miles from Antwerp... Instead of defending Antwerp, a pocket cut off from the rest of the allied front, the Belgians should have seen themselves as part of an overall Continental strategy and pulled back their Army to fight jointly with the French." (37)

King Albert I and his Belgian government left Antwerp on 9th October and the city surrendered the next day. The price of Churchill's intervention was that the Royal Naval Division lost a total of 2,610 men, most of whom were either prisoners of war or interned in the neutral Netherlands. Reaction to Churchill's adventure was highly critical and badly damaged his reputation. Asquith wrote that he thought the use of the professional Royal Marine Brigade was justified but "nothing can excuse Winston (who knew all the facts) from sending in the other Naval Brigades." (38)

David Lloyd George agreed with Asquith and told his mistress, Frances Stevenson, that he was "rather disgusted" with Churchill who had "behaved in a rather swaggering way when over there, standing for photographers and cinematographers with shells bursting near him". (39) Admiral Herbert Richmond wrote in his diary that "it is a tragedy that the Navy should be in such lunatic hands at this time". (40) The leader of the Conservative Party, Andrew Bonar Law was also highly critical of the Antwerp operation, describing it as "an utterly stupid business" and suggested that Churchill as having an "entirely unbalanced mind". (41) Chris Wrigley commented that "there was still something of the Boys' Hero in his behaviour." (42)

Churchill survived this disaster and it was another of his operations that brought him down. Churchill was concerned about the threat that Turkey posed to the British Empire and feared an attack on Egypt. He suggested that the seizure of the Dardanelles (a 41 mile strait between Europe and Asiatic Turkey that were overlooked by high cliffs on the Gallipoli Peninsula). At first the plan was initially rejected by H. H. Asquith, David Lloyd George, Admiral John Fisher and Lord Kitchener. Churchill did manage to persuade the commander of the British Mediterranean Squadron, Vice Admiral Sackville Carden, that the operation would be successful. (43)

On 11th January 1915, Vice Admiral Carden proposed a three-stage operation: the bombardment of the Turkish forts protecting the Dardanelles, the clearing of the minefields and then the invasion fleet traveling up the Straits, through the Sea of Marmara to Constantinople. Carden argued that to be successful the operation would need 12 battleships, 3 battle-cruisers, 3 light cruisers, 16 destroyers, six submarines, 4 sea-planes and 12 minesweepers. Whereas other members of the War Council were tempted to change their minds on the subject, Admiral Fisher threatened to resign if the operation took place. (44)

Admiral Fisher wrote to Admiral John Jellicoe, Commander of the Grand British Fleet, arguing: "I just abominate the Dardanelles operation, unless a great change is made and it is settled to be made a military operation, with 200,000 men in conjunction with the Fleet." (45) Maurice Hankey, secretary of the Imperial War Cabinet, agreed with Fisher and circulated a copy of the Committee of Imperial Defence assessment that was against a purely naval assault on the Dardanelles. (46)

Despite these objections, Churchill and Asquith decided that "the Dardanelles should go forward." On 19th February, 1915, Admiral Carden began his attack on the Dardanelles forts. The assault started with a long range bombardment followed by heavy fire at closer range. As a result of the bombardment the outer forts were abandoned by the Turks. The minesweepers were brought forward and managed to penetrate six miles inside the straits and clear the area of mines. Further advance up into the straits was now impossible. The Turkish forts were too far away to be silenced by the Allied ships. The minesweepers were sent forward to clear the next section but they were forced to retreat when they came under heavy fire from the Turkish batteries. (47)

Winston Churchill became impatient about the slow progress that Carden was making and demanded to know when the third stage of the plan was to begin. Admiral Carden found the strain of making this decision extremely stressful and began to have difficulty sleeping. On 15th March, Carden's doctor reported that the commander was on the verge of a nervous breakdown. Carden was sent home and replaced by Vice-Admiral John de Robeck, who immediately ordered the Allied fleet to advance up the Dardanelles Straits. (48) Reginald Brett, who worked for the War Council, commented: "Winston is very excited and jumpy about the Dardanelles; he says he will be ruined if the attack fails." (49)

On 18th March eighteen battleships entered the straits. At first they made good progress until the French ship, Bouvet struck a mine, heeled over, capsized and disappeared in a cloud of smoke. Soon afterwards two more ships, Irresistible and Ocean hit mines. Most of the men in these two ships were rescued but by the time the Allied fleet retreated, over 700 men had been killed. Overall, three ships had been sunk and three more had been severely damaged. Altogether about a third of the force was either sunk or disabled. (50)

At an Admiralty meeting on 19th March, Churchill and Fisher agreed that losses were only to be expected and that four more ships should be sent out to reinforce De Robeck, who responded with the news that he was reorganising his force so that some of the destroyers could act as minesweepers. Churchill now told Asquith that he was still confident that the operation would be successful and was "fairly pleased" with the situation. (51)

On 10th March, Lord Kitchener finally agreed that he was willing to send troops to the eastern Mediterranean to support any naval breakthrough. Churchill was able to secure the appointment of his old friend, General Ian Hamilton, as Commander of the British Forces. At a conference on 22nd March on board his flagship, Queen Elizabeth, it was decided that soldiers would be used to capture the Gallipoli peninsula. Churchill ordered De Roebuck to make another attempt to destroy the forts. He rejected the idea and said that the idea that the forts could be destroyed by gunfire had "conclusively proved to be wrong". Admiral Fisher agreed and warned Churchill: "You are just eaten up with the Dardanelles and can't think of anything else! Damn the Dardanelles! they'll be our grave." (52)

Arthur Balfour suggested delaying the landings. Churchill replied: "No other operation in this part of the world could ever cloak the defeat of abandoning the effort at the Dardanelles. I think there is nothing for it but to go through with the business, and I do not at all regret that this should be so. No one can count with certainty upon the issue of a battle. But here we have the chances in our favour, and play for vital gains with non-vital stakes." He wrote to his brother, Major Jack Churchill, who was one of those soldiers about to take part in the operation: "This is the hour in the world's history for a fine feat of arms, and the results of victory will amply justify the price. I wish I were with you." (53)

Asquith, Kitchener, Churchill and Hankey held a meeting on 30th March and agreed to go ahead with an amphibious landing. Leaders of the Greek Army informed Kitchener that he would need 150,000 men to take Gallipoli. Kitchener rejected the advice and concluded that only half that number was needed. Kitchener sent the experienced British 29th Division to join the troops from Australia, New Zealand and French colonial troops on Lemnos. Information soon reached the Turkish commander, Liman von Sanders, about the arrival of the 70,000 troops on the island. Sanders knew an attack was imminent and he began positioning his 84,000 troops along the coast where he expected the landings to take place. (54)

The attack that began on the 25th April, 1915 established two beachheads at Helles and Gaba Tepe. Another major landing took place at Sulva Bay on 6th August. By this time they arrived the Turkish strength in the region had also risen to fifteen divisions. Attempts to sweep across the peninsula by Allied forces ended in failure. By the end of August the Allies had lost over 40,000 men. General Ian Hamilton asked for 95,000 more men, but although supported by Churchill, Lord Kitchener was unwilling to send more troops to the area. (55)

Frances Stevenson reported that King George V had become concerned about Churchill's drinking. "The Dardanelles campaign, however, does not seem to be the success that was prophesied. Churchill very unwisely boasted at the beginning, when things were going well, that he had undertaken it against the advice of everyone else at the Admiralty... LG (David Lloyd George) says Churchill is very worried about the whole affair, and looking very ill. He is very touchy too. Last Monday LG was discussing the Drink question with Churchill, and Samuel and Montague were also present. Churchill put on the grand air, and announced that he was not going to be influenced by the King, and refused to give up his liquor - he thought the whole thing was absurd. LG was annoyed, but went on to explain a point that had been brought up. The next minute Churchill interrupted again. 'I don't see' - he was beginning, but LG broke in sharply: 'You will see the point', he rapped out, 'when you begin to understand that conversation is not a monologue!' Churchill went very red, but did not reply, and LG soon felt rather ashamed of having taken him up so sharply, especially in front of the other two." (56)

In the words of one historian, "In the annals of British military incompetence Gallipoli ranks very high indeed." (57) Churchill was blamed for the failed operation and Asquith told him he would have to be moved from his current post. Asquith was also involved in developing a coalition government. The Conservative leader, Andrew Bonar Law, insisted that Churchill should be removed from the War Cabinet. James Masterton-Smith, Churchill's private secretary, told Asquith, that "on no account ought Churchill to be allowed to remain at the Admiralty - he was most dangerous there". (58) Asquith agreed and Churchill's long-term enemy, Arthur Balfour, became the new First Lord of the Admiralty. Churchill was now relegated to the post of the Chancellorship of the Duchy of Lancaster. (59)

On 14th October, Hamilton was replaced by General Charles Munro. After touring all three fronts Munro recommended withdrawal. Lord Kitchener, initially rejected the suggestion but after arriving on 9th November 1915 he visited the Allied lines in Greek Macedonia, where reinforcements were badly needed. On 17th November, Kitchener agreed that the 105,000 men should be evacuated and put Munro in control as Commander-in-Chief Mediterranean. (60)

About 480,000 Allied troops took part in the Gallipoli campaign, including substantial British, French, Senegalese, Australian, New Zealand and Indian troops. The British had 205,000 casualties (43,000 killed). There were more than 33,600 ANZAC losses (over one-third killed) and 47,000 French casualties (5,000 killed). Turkish casualties are estimated at 250,000 (65,000 killed). "The campaign is generally regarded as an example of British drift and tactical ineptitude." (61)

In November, 1915, Churchill was removed as a member of the War Council. He now resigned as a minister and he told Asquith that his reputation would rise again when the whole story of the Dardanelles came out. He also criticised Asquith in the way the war had so far been managed. He ended his letter with the words: "Nor do I feel in times like these able to remain in well-paid inactivity. I therefore ask you to submit my resignation to the King. I am an officer, and I place myself unreservedly at the disposal of the military authorities, observing that my regiment is in France." (62)

Winston Churchill and Chemical Warfare

On 10th January 1919, Winston Churchill was appointed Secretary of State for War and Air. After the war the ending of price controls, prices rose twice as fast during 1919 as they had done during the worst years of the war. That year 35 million working days were lost to strikes, and on average every day there were 100,000 workers on strike - this was six times the 1918 rate. There were stoppages in the coal mines, in the printing industry, among transport workers, and the cotton industry. There were also mutinies in the military and two separate police strikes in London and Liverpool. (63)

The government formed a Cabinet Strike Committee to deal with the crisis. Churchill was the key member of the committee and deployed 23,000 troops, with 30,000 more in reserve, to protect the railways and drive food lorries. General Douglas Haig, attended the first meeting and described Churchill as being the "most energetic and talked more than anyone". In August 1919 he sent in troops to Liverpool to defeat a local police strike. His main enemy was the miners and he argued that: "This is the time to beat them. There is bound to be a fight. The English propertied classes are not going to take it lying down." (64)

Churchill was convinced that the military should be able to use chemical weapons against civilians in order to protect the British Empire. In April 1919, Churchill asked for permission to use mustard gas (a gas that causes severe blistering and kills about ten per cent of those affected) in Mesopotamia: "I do not understand this squeamishness about the use of gas... I am strongly in favour of using poisoned gases against uncivilised tribes. The moral effect should be so good that the loss of life should be reduced to a minimum... Gases can be used which cause great inconvenience and would leave a lively terror." (65)

Churchill also used chemical weapons in May 1919 to subdue rebels in Afghanistan. When the India Office objected to this policy he replied: "The objections of the India Office to the use of gas against natives are unreasonable. Gas is a more merciful weapon than high explosive shell and compels an enemy to accept a decision with less loss of life than any other agency of war. The moral effect is also very great. There can be no conceivable reason why it should not be resorted to." (66)

Churchill held a very low opinion of the Arabs and felt they deserved to lose their home to more advanced Europeans. He described the Arabs as acting like a "dog in a manger". He told the Peel Commission: "I do not agree that the dog in a manger has the final right to the manger, even though he may have lain there for a very long time. I do not admit that right. I do not admit, for instance, that a great wrong has been done to the Red Indians of America, or the black people of Australia. I do not admit that a wrong has been done to these people by the fact that a stronger race, a higher grade race, or at any rate, a more worldly-wise race, to put it that way, has come in and taken their place." (67)

However, his main enemy during this period was communism. He feared that the revolution would spread from Russia to western Europe. All the members of the government opposed Bolshevism but no one hated it like he did. He told the House of Commons that "Bolshevism is not a policy; it is a disease. It is not a creed; it is a pestilence." (68) He described the Bolsheviks as "swarms of typhus-bearing vermin". (69) In article in The Evening News he claimed that the Bolsheviks had created "a poisoned Russia, an infected Russia, a plague bearing Russia." (70)

Churchill blamed Jews for the Russian Revolution. He told Lord George Curzon, the Foreign Secretary, that in his opinion that the Bolsheviks had created a "tyrannical government of these Jew Commissars". In a letter to Frederick Smith he described them as "these Semitic conspirators" and "Semitic internationalists". In one speech he called the Russian government "a world wide communistic state under Jewish domination." At a public meeting in Sunderland he spoke of "the international Soviet of the Russian and Polish Jew." (71)

In an article in the Illustrated Sunday Herald he argued: "The part played in the creation of Bolshevism and in the actual bringing about of the Russian Revolution by these international and for the most part atheistic Jews ... is certainly a very great one; it probably outweighs all others. With the notable exception of Lenin, the majority of the leading figures are Jews. Moreover, the principal inspiration and driving power comes from Jewish leaders ... The same evil prominence was obtained by Jews in (Hungary and Germany, especially Bavaria)." (72)

Churchill had supported the sending of British troops to help the White Army in the Russian Civil War, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel John Ward. However, it had not been a success Ward later told one of his officers, Brian Horrocks: "I believe we shall rue this business for many years. It is always unwise to intervene in the domestic affairs of any country. In my opinion the Reds are bound to win and our present policy will cause bitterness between us for a long time to come." Horrocks agreed: "How right he was: there are many people today who trace the present international impasse back to that fatal year of 1919." (73)

Churchill argued that the British had not sent enough troops. He argued in a Cabinet meeting that Britain should intervene "thoroughly, with large forces, abundantly supplied with mechanical appliances". He also suggested a campaign to recruit a volunteer army to fight in Russia. David Lloyd George admitted that the Cabinet was united in its hostility to the Bolsheviks but they did have support in Russia. He added that Britain had no right to interfere in their internal affairs and anyway lacked the means to do so. (74)

Winston Churchill now took the controversial decision to use the stockpiles of M Device against the Red Army. He was supported in this by Sir Keith Price, the head of the chemical warfare, at Porton Down. He declared it to be the "right medicine for the Bolshevist" and the terrain would enable it to "drift along very nicely". Price agreed with Churchill that the use of chemical weapons would lead to a rapid collapse of the Bolshevik government in Russia: "I believe if you got home only once with the Gas you would find no more Bolshies this side of Vologda." (75)

In the greatest secrecy, 50,000 M Devices were shipped to Archangel, along with the weaponry required to fire them. Winston Churchill sent a message to Major-General William Ironside: "Fullest use is now to be made of gas shell with your forces, or supplied by us to White Russian forces." He told Ironside that this "thermogenerator of arsenical dust that would penetrate all known types of protective mask". Churchill added that he would very much like the "Bolsheviks" to have it. Churchill also arranged for 10,000 respirators for the British troops and twenty-five specialist gas officers to use the equipment. (76)

Some one leaked this information and Winston Churchill was forced to answer questions on the subject in the House of Commons on 29th May 1919. Churchill insisted that it was the Red Army who was using chemical warfare: "I do not understand why, if they use poison gas, they should object to having it used against them. It is a very right and proper thing to employ poison gas against them." His statement was untrue. There is no evidence of Bolshevik forces using gas against British troops and it was Churchill himself who had authorised its initial use some six weeks earlier. (77)

On 27th August, 1919, British Airco DH.9 bombers dropped these gas bombs on the Russian village of Emtsa. According to one source: "Bolsheviks soldiers fled as the green gas spread. Those who could not escape, vomited blood before losing consciousness." Other villages targeted included Chunova, Vikhtova, Pocha, Chorga, Tavoigor and Zapolki. During this period 506 gas bombs were dropped on the Russians. Lieutenant Donald Grantham interviewed Bolshevik prisoners about these attacks. One man named Boctroff said the soldiers "did not know what the cloud was and ran into it and some were overpowered in the cloud and died there; the others staggered about for a short time and then fell down and died". Boctroff claimed that twenty-five of his comrades had been killed during the attack. Boctroff was able to avoid the main "gas cloud" but he was very ill for 24 hours and suffered from "giddiness in head, running from ears, bled from nose and cough with blood, eyes watered and difficulty in breathing." (78)

Major-General William Ironside told David Lloyd George that he was convinced that even after these gas attacks his troops would not be able to advance very far. He also warned that the White Army had experienced a series of mutinies (there were some in the British forces too). Lloyd George agreed that Ironside should withdraw his troops. This was completed by October. The remaining chemical weapons were considered to be too dangerous to be sent back to Britain and therefore it was decided to dump them into the White Sea. (79)

An uprising of more than 100,000 armed tribesmen took place in 1920. It was estimated that around 25,000 British and 80,000 Indian troops would be needed to control the country. However, he argued that if Britain relied on air power, you could cut these numbers to 4,000 (British) and 10,000 (Indian). The government was convinced by this argument and it was decided to send the recently formed Royal Air Force to Iraq. Over the next few months the RAF dropped 97 tons of bombs killing 9,000 Iraqis. This failed to end the resistance and Arab and Kurdish uprisings continued to pose a threat to British rule. Churchill decided to use chemical weapons on the rebels. He told Sir Hugh Trenchard, Chief of the Air Staff, that "mustard gas could be used "without inflicting grave injury" on its victims. (80)

In the 1922 General Election the Conservative Party did not put up a candidate against Winston Churchill. His main rival was E. D. Morel, the Labour Party candidate. Morel was the founder of the Union of Democratic Control (UDC), the main organisation that opposed the First World War. Another opponent was William Gallacher, a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, who had also been an anti-war activist. From his Dorset Square nursing home Churchill attacked the policies of Morel and Gallacher: "A predatory and confiscatory programme fatal to the reviving prosperity of the country, inspired by class jealously and the doctrines of envy, hatred and malice, is appropriately championed in Dundee by two candidates both of whom had to be shut up during the late war in order to prevent them further hampering the national defence." (81)

Churchill launched a bitter campaign against Morel and Gallacher and accused them of belonging to a "band of degenerate international intellectuals". He added: "Mr Gallacher is only Mr Morel with the courage of his convictions, and Trotsky is only Mr Gallacher with the power to murder those whom he cannot convince." In this working-class constituency Churchill's obvious wealth and English upper-class attitudes, worked against him. On 13th November 1922 Churchill tried to make a public speech but he was shouted down and had to abandon the meeting. (82) During the campaign Benito Mussolini took power in Italy and Edwin Scrymgeour, observed that it would not surprise him in the event of civil war in Britain "if Mr Churchill were at the head of the Fascisti party". (83)

Morel defeated Churchill by 30,292 votes to 20,466. The Conservative Party achieved 344 seats and formed the next government. The Labour Party, who promised to nationalise the mines and railways, a massive house building programme and to revise the peace treaties, went from 57 to 142 seats. In third place came the Liberals. They accounted for nearly a third of the vote but were badly split - Lloyd George's faction won forty-seven seats, those supporting H. H. Asquith, forty and uncommitted members twenty-nine. (84)

General Edward Louis Spears, offered to resign as coalition Liberal MP for Loughborough in order that Churchill could return to the House of Commons. Churchill refused as he now realised that the Liberal Party would never again take power. If he wanted to become a minister again he would have to rejoin the Conservative Party. It was not until May, 1923, that he made it clear he intended to return to politics. In a speech that he made at the Aldwych Club he made an attack on Asquith who had refused to work with the Conservatives. He said it was the responsibility of politicians to do everything possible to prevent the growth of the Labour Party. He wanted to join forces with any party with "the clear purpose of rallying the greatest number of persons of all classes... to the defence of the existing constitution" so as to resist "the ceaseless advance and... victorious enforcement of the levelling and withering doctrines of socialism". (85)

On 22nd February, 1924, Churchill discovered there was to be a by-election in the strongly Conservative seat of Westminster Abbey. He approached the Conservative Party and offered to become its candidate. This was rejected by Stanley Baldwin and was told to wait for another opportunity. Austen Chamberlain wrote to Churchill's friend, Frederick Smith, Lord Birkenhead: "We want to get him (Churchill) and his friends over, and although we cannot give him the Abbey seat, Baldwin will undertake to find him a good seat later on when he will have been able to develop naturally his new line and make his entry into our ranks much easier than it would be today. Our only fear is lest Winston should try and rush the fence." (86)

Churchill explained: "I found myself free a few months later to champion the anti-Socialist cause in the Westminster by-election, and so regained for a time at least the goodwill of all those strong Conservative elements, some of whose deepest feelings I share and can at critical moments express, although they have never liked or trusted me. But for my erroneous judgment in the General Election of 1923 I should have never have regained contact with the great party into which I was born and from which I had been severed by so many years of bitter quarrel. (87)

Winston Churchill ignored the advice of Austen Chamberlain and stood as an anti-socialist candidate, because the Labour Government was a challenge to "our existing economic and social civilisation". Otho Nicholson the Conservative candidate won by 43 votes but Churchill's intervention allowed Fenner Brockway, the Labour candidate to finish a close third. Soon afterwards he was given the safe Conservative seat of Epping. (88)

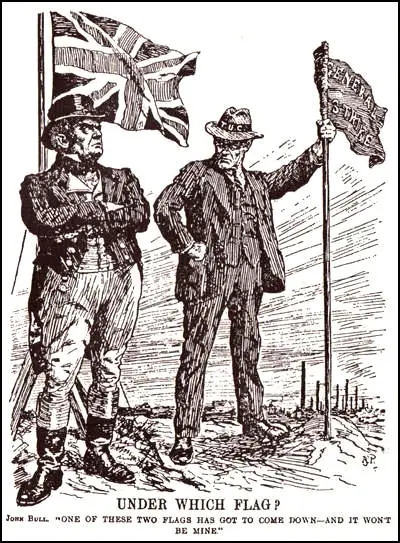

Winston Churchill: "No, it isn't. I thought of it first."

Leonard Raven-Hill, The Fight for the Favourite (4th June, 1924)

During the 1924 General Election campaign he argued "I represent uncompromising opposition to the subversive movement of Socialism, and I equally oppose those who are willing to make... compromising bargains with the Socialists." (89) In another speech he insisted that "I am in favour of developing trade within the Empire, but I am not in favour of risking our money on Russia and other foreigners." (90)

Chancellor of the Exchequer

Winston Churchill defeated the Liberal candidate, Gilbert Granville Sharp, by nearly 10,000 votes. Austen Chamberlain advised Stanley Baldwin to put Churchill in the Cabinet: "If you leave him out, he will be leading a Tory rump in six months' time." (91) Thomas Jones, one of Baldwin's leading advisers, commented: "I would certainly have him inside, not out" and suggested sending him to the Board of Trade or the Colonial Office. Baldwin eventually decided to offer him the post of Chancellor of the Exchequer. Churchill replied: "This fulfils my ambition. I still have my father's robes as Chancellor. I shall be proud to serve you in this splendid office." (92)

Churchill had no experience of financial or economic matters when he went to the Treasury in November 1924. He made it clear to Sir Richard Hopkins, the chairman of the Board of Inland Revenue that he had no intention of increasing taxes on the rich: "As the tide of taxation recedes it leaves the millionaires stranded on the peaks of taxation to which they have been carried by the flood... Just as we have seen the millionaire left close to the high water mark and the ordinary Super Tax payer draw cheerfully away from him, so in their turn the whole class of Super Tax payer will be left behind on the beach as the great mass of the Income Tax payers subside into the refreshing waters of the sea." (93)

Churchill's first major decision concerned the Gold Standard. Britain had left the gold standard in 1914 as a wartime measure, but it was always assumed by the City of London financial institutions that once the war was over Britain would return to the mechanism that had seemed so successful before the war in providing stability, low interest rates and a steady expansion in world trade. However, at the end of the First World War, the British economy was in turmoil. After a short-term boom in 1919 gross domestic fell by six per cent and unemployment rose rapidly to 23 per cent. (94)

Montagu Norman, the governor of the Bank of England and Otto Niemeyer, a senior figure at the Treasury, were both strong supporters of a return to the gold standard. Niemeyer said to dodge the issue now would be to show that Britain had never really "meant business" about the Gold Standard and that "our nerve had failed when the stage was set." Norman added that in the opinion "of educated and reasonable men" there was no alternative to a return to Gold. The Chancellor would no doubt be attacked whatever he did but "in the former case (Gold) he will be abused by the ignorant, the gamblers and the antiquated industrialists". (95)

Churchill was not convinced as he was aware of the alternative ideas of John Maynard Keynes. He told Niemeyer: "The Treasury has never, it seems to me, faced the profound significance of what Mr Keynes calls `the paradox of unemployment amidst dearth'. The Governor shows himself perfectly happy in the spectacle of Britain possessing the finest credit in the world simultaneously with a million and a quarter unemployed. Obviously if these million and a quarter were usefully and economically employed, they would produce at least £100 a year a head, instead of costing up at least £50 a head in doles." (96)

Churchill also sought the advice of Philip Snowden, who had served as Chancellor of the Exchequer, in the previous Labour government. Snowden said he was in favour of a return to the Gold Standard at the earliest possible moment. On 17th March, 1925, Churchill gave a dinner that was attended by supporters and opponents of returning to the Gold Standard. He admitted that Keynes provided the better arguments but as a matter of practical politics he had no alternative but to go back to Gold. (97)

Roy Jenkins has argued that the return to the Gold Standard was the gravest mistake of the Baldwin government: "Churchill was deliberately a very attention-attracting Chancellor. He wanted his first budget to make a great splash, which it did, and a considerable contribution to the spray was made by the announcement of the return to Gold. Reluctant convert although he had been, he therefore deserved the responsibility and, if it be so judged, a considerable part of the blame." (98)

Other measures in his first budget included a move towards Imperial Preference and some modest tariffs to help members of the British Empire: sugar (West Indies), tobacco (Kenya and Rhodesia), wines (South Africa and Australia) and dried fruits (Middle East). This marked his move away from the doctrinaire liberalism of his earlier years. He also announced a reduction of income tax by sixpence to four shillings in the pound. "He made out to be beneficial to the worse off as well as the prosperous, but which pleased the latter most." The wealthy were also pleased by a reduction in super tax. (99)

Churchill was attempting to deal with the social problems of the country without recourse to Socialism. Philip Snowden, the former Labour chancellor of the exchequer, called it "the worst rich man's budget ever presented". (100) Treasury officials, including the Permanent Secretary Sir Warren Fisher, thought that it was a very bad budget as it gave too much away and so would cause problems for the next few years. Fisher told Neville Chamberlain that Churchill was "a lunatic... an irresponsible child, not a grown man" and complained that all the senior officials in the Treasury had lost heart - "they never know where they are or what hare W.C. will start". (101)

As a result of returning to the Gold Standard the country took little part in the world boom from 1925 to 1929 and its share of world markets continued to fall. The balance of payments surplus recorded in 1924 disappeared and overpriced British exports slumped. The overvalued pound meant that costs had to be reduced in an unavailing attempt to keep exports competitive. This meant cuts in labour costs at a time when real wages were already below 1914 levels. Attempts to impose further wage reductions inevitably led to industrial disputes, lock-outs and strikes. It has been estimated that returning to the Gold Standard made as many as 700,000 people unemployed. (102)

Despite the problem of low Government revenues Churchill was determined not to increase personal taxes. In 1925 the majority of people did not pay income tax - only 2½ million people were liable and just 90,000 paid super-tax. The standard rate of income tax was reduced from four shillings and sixpence to four shillings in the pound. The super-tax was reduced by £10 million, which was substantial in relation to the total yield of the tax at £60 million: "This was of substantial benefit to the rich, not only as individual taxpayers but also in the capacity of many of them as shareholders, for income tax was then the principal form of company taxation." (103)

In a letter to James Gascoyne-Cecil, 4th Marquess of Salisbury, the leader of the House of Lords, he argued that "the rich, whether idle or not, are already taxed in this country to the very highest point compatible with the accumulation of capital for further production." (104) In a second letter he stated that cutting taxes was a "class measure" that was designed to help the comfortably off and the rich." (105)

Churchill was warned that he needed to find ways of balancing the budget. He was unwilling to increase income-tax and super-tax and so he decided to raid the "Road Fund", for which revenue had risen to the substantial sum of £21.5 million. It was assumed that this money would be used for building new roads. Churchill disagreed and took £7 million from the Road Fund that year. When the Automobile Association complained about this Churchill wrote "such contentions are absurd, and constitute at once an outrage upon the sovereignty of Parliament and upon commonsense." (106)

Churchill's social conservatism was also apparent during discussions within the Government over changes to unemployment insurance. The scheme that the Liberal government had introduced in 1911 had collapsed after the war because of large-scale structural unemployment, particularly among trades that were not covered by the scheme. A benefit (the dole) was first introduced for unemployed ex-servicemen, later extended to others and then made subject to a means test in 1922. Churchill thought that far too many people were drawing the "dole". (107)

Winston Churchill spoke in the House of Commons of the "growing up of a habit of qualifying for unemployment relief" and the need for an enquiry. (108) Three weeks later he told Thomas Jones, the Deputy Secretary of the Cabinet, that "there should be an immediate stiffening of the administration, and the position should be made much more difficult for young unmarried men living with relatives, wives with husbands at work, aliens, etc." (109)

Winston Churchill: "I will not tell a lie. With my little hatchet

I have failed to make much impression. But I will keep trying. "

Leonard Raven-Hill, Last Orders (5th May, 1926)

Churchill wrote to Arthur Steel-Maitland, the Minister of Labour, to explain his ideas. He suggested that when the legislation to pay for the dole expired in 1926, rather than reduce the benefit, as most of his colleagues wanted to do, they should abolish it altogether. Churchill said: "It is profoundly injurious to the state that this system should continue; it is demoralising to the whole working class population... it is charitable relief; and charitable relief should never be enjoyed as a right." Churchill told Steel-Maitland that the huge number of unemployed families would have to depend on private charity once their insurance benefits were exhausted. The Government might make some donations to charities but money would only be given to "deserving cases" and that "by proceeding on the present lines we are rotting the youth of the country and rupturing the mainsprings of its energies". (110)

Churchill attempted to get his ideas supported by Stanley Baldwin, the prime minister: "I am thinking less about saving the exchequer than about saving the moral fibre of our working classes." (111) Churchill did not get his way. The other members of the Government, regardless of any possible moral consequences, could not face the political impact of ending the ‘dole' at a time when over a million people were out of work. "Nevertheless he was able to achieve the objective he referred to as less important – reducing the cost to the Exchequer by cutting the level of benefits for the unemployed. In 1926 the Treasury's contribution to the health and unemployment schemes was reduced by eleven per cent (to save £2.5 million on the health scheme) and a Royal Commission recommendation to extend the schemes was ignored. In 1927 the unemployment benefit for single men was reduced by a shilling a week." (112)

Winston Churchill was successful with persuading his cabinet colleagues that the test that the unemployed had to pass was stiffened: they now had to prove that they were "genuinely seeking work" even if there were no jobs available. The Government was able to increase, as a matter of deliberate policy, the rejection rate from three per cent in 1924 to over eighteen per cent by 1927. In November 1925 he was also able to convince his colleagues that "to the utmost extent possible Government unemployment relief schemes should be closed down" in order to save money. (113)

The General Strike

Churchill was a strong supporter of introducing legislation to weaken the labour movement. He was especially keen to force trade union members to voluntarily 'contract in' to pay the political levy to the Labour Party. The right-wing Tory MP, Frederick A. Macquisten, introduced his own private members bill on the subject. Macquisten argued that trade unions were guilty of imposing taxes on its members. "What I am proposing now is to relieve the working man of this liability to be taxed." (114)

In the House of Commons, Churchill supported the measure but Stanley Baldwin rejected the idea on moral grounds as the the trade unions were weak at this time because of increasing unemployment. "We find ourselves, after these two years in power, in possession of perhaps the greatest majority our party has ever had, and with the general assent of the country. Now how did we get there? It was not by promising to bring this Bill in; it was because, rightly or wrongly, we succeeding in creating an impression throughout the country that we stood for stable Government and for peace in the country between all classes of the community." He appealed to his own Party's sense of British fair-play, they should not, he said, push home their advantage at a "time like this". Baldwin claimed that "stability at home and abroad was what was needed" and he was unwilling to "fire the first shot". He concluded with an appeal from the Book of Common Prayer: "Give peace in our time, O Lord." (115)

On 30th June 1925 the mine-owners announced that they intended to reduce the miner's wages. Will Paynter later commented: "The coal owners gave notice of their intention to end the wage agreement then operating, bad though it was, and proposed further wage reductions, the abolition of the minimum wage principle, shorter hours and a reversion to district agreements from the then existing national agreements. This was, without question, a monstrous package attack, and was seen as a further attempt to lower the position not only of miners but of all industrial workers." (116)

On 23rd July, 1925, Ernest Bevin, the general secretary of the Transport & General Workers Union (TGWU), moved a resolution at a conference of transport workers pledging full support to the miners and full co-operation with the General Council in carrying out any measures they might decide to take. A few days later the railway unions also pledged their support and set up a joint committee with the transport workers to prepare for the embargo on the movement of coal which the General Council had ordered in the event of a lock-out." (117) It has been claimed that the railwaymen believed "that a successful attack on the miners would be followed by another on them." (118)

In an attempt to avoid a General Strike, the prime minister, Stanley Baldwin, invited the leaders of the miners and the mine owners to Downing Street on 29th July. The miners kept firm on what became their slogan: "Not a minute on the day, not a penny off the pay". Herbert Smith, the president of the Miners' Federation of Great Britain, told Baldwin: "We have now to give". Baldwin insisted there would be no subsidy: "All the workers of this country have got to take reductions in wages to help put industry on its feet." (119)

The following day the General Council of the Trade Union Congress triggered a national embargo on coal movements. On 31st July, the government capitulated. It announced an inquiry into the scope and methods of reorganization of the industry, and Baldwin offered a subsidy that would meet the difference between the owners' and the miners' positions on pay until the new Commission reported. The subsidy would end on 1st May 1926. Until then, the lockout notices and the strike were suspended. This event became known as Red Friday because it was seen as a victory for working class solidarity. (120)

Herbert Smith pointed out that the real battle was to come: "We have no need to glorify about a victory. It is only an armistice, and it will depend largely how we stand between now and May 1st next year as an organisation in respect of unity as to what will be the ultimate results. All I can say is, that it is one of the finest things ever done by an organisation." (121)

Red Friday was a great success for Smith and Arthur J. Cook, general secretary of the MFGB. However, Margaret Morris has argued that they had a difficult relationship: "Smith was temperamentally and politically the antithesis of Cook. Where Cook was emotional and voluble, Smith was dour and short of words. He was an old-style union leader, used to dominating the miners in Yorkshire... Relations between Smith and Cook were not always harmonious; neither of them really trusted the other's judgement, but each could respect that the other was dedicated to serving the miners. Neither of them was a very good negotiator: Cook was too excitable, and Smith perhaps a little too defensive in his tactics." (122)

The General Strike began on 3rd May, 1926. Arthur Pugh, the chairman of the Trade Union Congress, was put in charge of the strike. The Trade Union Congress adopted the following plan of action. To begin with they would bring out workers in the key industries - railwaymen, transport workers, dockers, printers, builders, iron and steel workers - a total of 3 million men (a fifth of the adult male population). Only later would other trade unionists, like the engineers and shipyard workers, be called out on strike. Ernest Bevin, the general secretary of the Transport & General Workers Union (TGWU), was placed in charge of organising the strike. (123)

The TUC decided to publish its own newspaper, The British Worker, during the strike. Some trade unionists had doubts about the wisdom of not allowing the printing of newspapers. Workers on the Manchester Guardian sent a plea to the TUC asking that all "sane" newspapers be allowed to be printed. However, the TUC thought it would be impossible to discriminate along such lines. Permission to publish was sought by George Lansbury for Lansbury's Labour Weekly and H. N. Brailsford for the New Leader. The TUC owned Daily Herald also applied for permission to publish. Although all these papers could be relied upon to support the trade union case, permission was refused. (124)

The government reacted by publishing The British Gazette. Baldwin gave permission to Winston Churchill to take control of this venture and his first act was commandeer the offices and presses of The Morning Post, a right-wing newspaper. The company's workers refused to cooperate and non-union staff had to be employed. Baldwin told a friend that he gave Churchill the job because "it will keep him busy, stop him doing worse things". He added he feared that Churchill would turn his supporters "into an army of Bolsheviks". (125)

Churchill, along with Frederick Smith, Lord Birkenhead, were members of the government who saw the strike as "an enemy to be destroyed." Lord Beaverbrook described him as being full of the "old Gallipoli spirit" and in "one of his fits of vainglory and excessive excitement". Thomas Jones attempted to develop a plan that would bring the dispute to an end. Churchill was furious and said that the government should reject a negotiated settlement. Jones described Churchill as a "cataract of boiling eloquence" and told him that "we are at war" and the battle should continue until the government won. (126)

John C. Davidson, the chairman of the Conservative Party, commented that Churchill was "the sort of man whom, if I wanted a mountain to be moved, I should send for at one. I think, however, that I should not consult him after he had moved the mountain if I wanted to know where to put it." (127) Neville Chamberlain found Churchill's approach unacceptable and wrote in his diary that "some of us are going to make a concerted attack on Winston... he simply revels in this affair, which he will continually treat and talk of as if it were 1914." (128)

Davidson, who had been put in overall charge of the government's media campaign, grew increasingly frustrated by Churchill's willingness to distort or suppress any item which might be vaguely favourable to "the enemy". Davidson argued that Churchill's behaviour became so extreme that he lost the support of the previously loyal Lord Birkenhead: "Winston, who had it firmly in his mind that anybody who was out of work was a Bolshevik; he was most extraordinary and never have I listened to such poppycock and rot." (129)

Churchill called for the government to seize union funds. This was rejected and Churchill was condemned for his "wild ways". John Charmley has argued that "Churchill had a sentimentalist upper-class view of grateful workers co-operating with their betters for the good of the nation; he neither understood, nor realised that he did not understand, the Labour movement. To have written about the TUC leaders as though they were potential Lenins and Trotskys said more about the state of Churchill's imagination than it did about his judgment." (130)

Walter Citrine, the general secretary of the Trade Union Congress (TUC), was desperate to bring an end to the General Strike. He argued that it was important to reopen negotiations with the government. His view was "the logical thing is to make the best conditions while our members are solid". Baldwin refused to talk to the TUC while the General Strike persisted. Citrine therefore contacted Jimmy Thomas, the general secretary of the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR), who shared this view of the strike, and asked him to arrange a meeting with Herbert Samuel, the Chairman of the Royal Commission on the Coal Industry. (131)

Without telling the miners, the TUC negotiating committee met Samuel on 7th May and they worked out a set of proposals to end the General Strike. These included: (i) a National Wages Board with an independent chairman; (ii) a minimum wage for all colliery workers; (iii) workers displaced by pit closures to be given alternative employment; (iv) the wages subsidy to be renewed while negotiations continued. However, Samuel warned that subsequent negotiations would probably mean a reduction in wages. These terms were accepted by the TUC negotiating committee, but were rejected by the executive of the Miners' Federation. (132)

Herbert Smith was furious with the TUC for going behind the miners back. One of those involved in the negotiations, John Bromley of the NUR, commented: "By God, we are all in this now and I want to say to the miners, in a brotherly comradely spirit... this is not a miners' fight now. I am willing to fight right along with them and suffer as a consequence, but I am not going to be strangled by my friends." Smith replied: "I am going to speak as straight as Bromley. If he wants to get out of this fight, well I am not stopping him." (133)

Walter Citrine wrote in his diary: "Miner after miner got up and, speaking with intensity of feeling, affirmed that the miners could not go back to work on a reduction in wages. Was all this sacrifice to be in vain?" Citrine quoted Cook as saying: "Gentleman, I know the sacrifice you have made. You do not want to bring the miners down. Gentlemen, don't do it. You want your recommendations to be a common policy with us, but that is a hard thing to do." (134)

Herbert Smith asked Arthur Pugh if the decision was "the unanimous decision of your Committee?" Pugh replied that it was the view that the General Strike should come to an end. Smith pleaded for further negotiations. However, Pugh was insistent: "That is it. That is the final decision, and that is what you have to consider as far as you are concerned, and accept it." (135)

On the 11th May, at a meeting of the Trade Union Congress General Committee, it was decided to accept the terms proposed by Herbert Samuel and to call off the General Strike. The following day, the TUC General Council visited 10 Downing Street and attempted to persuade the Government to support the Samuel proposals and to offer a guarantee that there would be no victimization of strikers.

Baldwin refused but did say if the miners returned to work on the current conditions he would provide a subsidy for six weeks and then there would be the pay cuts that the Mine Owners Association wanted to impose. He did say that he would legislate for the amalgamation of pits, introduce a welfare levy on profits and introduce a national wages board. The TUC negotiators agreed to this deal. As Lord Birkenhead, a member of the Government was to write later, the TUC's surrender was "so humiliating that some instinctive breeding made one unwilling even to look at them." (136)

In 1927 the British Government passed the Trade Disputes and Trade Union Act. This act made all sympathetic strikes illegal, ensured the trade union members had to voluntarily 'contract in' to pay the political levy to the Labour Party, forbade Civil Service unions to affiliate to the TUC, and made mass picketing illegal. As A. J. P. Taylor has pointed out: "The attack on Labour party finance came ill from the Conservatives who depended on secret donations from rich men." (137)

The legislation defined all sympathetic strikes as illegal, confining the right to strike to "the trade or industry in which the strikers are engaged". The funds of any union engaging in an illegal strike was liable in respect of civil damages. It also limited the right to picket, in terms so vague that almost any form of picketing might be liable to prosecution. As Julian Symons has pointed out: "More than any other single measure, the Trade Disputes Act caused hatred of Baldwin and his Government among organized trade unionists." (138)

One of the results of this legislation was that trade union membership fell below the 5,000,000 mark for the first time since 1926. However, despite its victory over the trade union movement, the public turned against the Conservative Party. Over the next three years the Labour Party won all the thirteen by-elections that took place. According to Martin Pugh, the author of Speak for Britain: A New History of the Labour Party (2010) the General Strike had "made a major impact on the general public by detracting from Baldwin's attempts to be seen as even-handed and by undermining the Conservatives in industrial constituencies." (139)

In January 1929, 1,433,000 people in Britain were out of work. Stanley Baldwin was urged to take measures that would protect the depressed iron and steel industry. Baldwin ruled this out owing to the pledge against protection which had been made at the 1924 election. Agriculture was in an even worse condition, and here again the government could offer little assistance without reopening the dangerous tariff issue. Baldwin was considered to be a popular prime minister and he fully expected to win the general election that was to take place on 30th May. (140)

In its manifesto the Conservative Party blamed the General Strike for the country's economic problems. "Trade suffered a severe set-back owing to the General Strike, and the industrial troubles of 1926. In the last two years it has made a remarkable recovery. In the insured industries, other than the coal mining industry, there are now 800,000 more people employed and 125,000 fewer unemployed than when we assumed office... This recovery has been achieved by the combined efforts of our people assisted by the Government's policy of helping industry to help itself. The establishment of stable conditions has given industry confidence and opportunity." (141)

The Labour Party attacked the record of Baldwin's government: "By its inaction during four critical years it has multiplied our difficulties and increased our dangers. Unemployment is more acute than when Labour left office.... The Government's further record is that it has helped its friends by remissions of taxation, whilst it has robbed the funds of the workers' National Health Insurance Societies, reduced Unemployment Benefits, and thrown thousands of workless men and women on to the Poor Law. The Tory Government has added £38,000,000 to indirect taxation, which is an increasing burden on the wage-earners, shop-keepers and lower middle classes." (142)

Winston Churchill and the Great Depression

A massive campaign in the Tory press against the proposal of increased public spending was very successful. In the 1929 General Election the Conservatives won 8,656,000 votes (38%), the Labour Party 8,309,000 (37%) and the Liberals 5,309,000 (23%). However, the bias of the system worked in Labour's favour, and in the House of Commons the party won 287 seats, the Conservatives 261 and the Liberals 59. A. J. P. Taylor has argued that the idea of increasing public spending would be good for the economy, was difficult to grasp. "It seemed common sense that a reduction in taxes made the taxpayer richer... Again it was accepted doctrine that British exports lagged because costs of production were too high; and high taxation was blamed for this about as much as high wages." (143). John Maynard Keynes later commented: "The difficulty lies, not in the new ideas, but in escaping from the old ones, which ramify, for those brought up as most of us have been, into every corner of our minds." (144)

Winston Churchill's handling of the economy was blamed for the Conservative government's defeat in 1929. In 1931 when Stanley Baldwin, the leader of the party joined the National Government, he refused to allow Churchill to join the team because his views were considered to be too extreme. This included his idea that "democracy is totally unsuited to India" because they were "humble primitives". When the Viceroy of India, Edward Wood, told him that his opinions were out of date and that he ought to meet some Indians in order to understand their views, he rejected the suggestion: "I am quite satisfied with my views of India. I don't want them disturbed by any bloody Indian." (145)

Churchill also questioned the idea of democracy and asked "whether institutions based on adult suffrage could possibly arrive at the right decision upon the intricate propositions of modern business and finance". He then suggested a semi-corporatist, anti-democratic alternative that would have been similar to the authoritarian state imposed on Italy by Benito Mussolini and Germany by Adolf Hitler. Churchill had been an early supporter of Mussolini: "Fascismo's triumphant struggle against the bestial appetites and passions of Leninism... proved the necessary antidote to the Communist poison." (146)