On this day on 27th August

On this day in 1819 Richard Carlile publishes article in The Republican on the Peterloo Massacre.

The massacre of the unoffending inhabitants of Manchester, on the 16th of August, by the Yeomanry Cavalry and Police at the instigation of the Magistrates, should be the daily theme of the Press until the murderers are brought to justice.

Captain Nadin and his banditti of Police, are hourly engaged to plunder and ill-use the peaceable inhabitants; whilst every appeal from those repeated assaults to the Magistrates for redress, is treated by them with derision and insult.

Every man in Manchester who avows his opinions on the necessity of reform, should never go unarmed - retaliation has become a duty, and revenge an act of justice.

On this day in 1875 Katharine Dexter was born. One of the first women to study at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), she received a degree in biology in 1904.

Later that year Katharine married Stanley McCormick, the son of Cyrus McCormick, the inventor of the mechanical harvester. However, two years later Katharine's husband was diagnosed as suffering from schizophrenia.

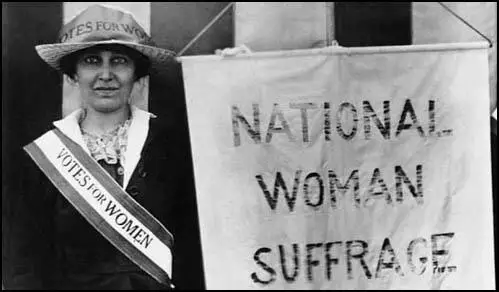

An active supporter of women's rights, McCormick worked with Margaret Sanger in her campaign to give birth control advice to women. A prominent member of the American Woman Suffrage Association, McCormick served as vice president and treasury of the organization.

Katharine McCormick was one of the main opponents of Alice Paul and the militant wing of the American Woman Suffrage Association that wanted to introduce the methods used by the Women's Social and Political Union in Britain. Eventually this group split to form the Congressional Union for Women Suffrage (CUWS).

In 1919 McCormick joined with Carrie Chapman Catt to establish the League of Women Voters. McCormick used the wealth she inherited from her husband to fund projects such as the research that led to the discovery and development of an oral hormone contraceptive.

Katharine McCormick died on 28th December, 1967. She left a large sum to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and wrote in her will: "Since my graduation in 1904 I have wished to express my gratitude to the Institute for its advanced policy of scientific training which has been of inestimable value to me throughout my life."

McCormick's will provided $5 million to the Stanford University School of Medicine to support female physicians, $5 million to the Planned Parenthood Federation of America , which funded the Katharine Dexter McCormick Library in Manhattan, New York City, $1 million to the Worcester Foundation for Experimental Biology and $500,000 to the Chicago Art Institute.

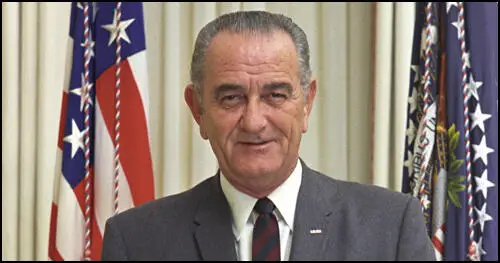

On this day in 1908 Lyndon B. Johnson was born in Stonewall, Texas. Although both his father and grandfather had served in the Texas legislature, the family were poor. After leaving school he did a variety of menial jobs before studying at the Texas State Teachers College at San Marcos.

In 1930 Johnson began teaching at the Sam Houston High School. A member of the Democratic Party, Johnson became involved in local politics and in 1932 he went to Washington as legislative assistant to the Congressman, Richard M. Kleberg. A strong supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, in 1935 Johnson was appointed director of the National Youth Administration.

In 1936 Johnson was a candidate for Austin's Tenth Congressional District. Welly Kennon Hopkins met Johnson and told his friend, Charles Edward Marsh, about this passionate "New Dealer". Marsh was also a supporter of the New Deal and ordered the editors of his two newspapers in Austin to back him. Hopkins claimed that Johnson's victory was in "no small part thanks to Marsh's editorial support" and suspected that he helped the young politician "as a way of extending his own influence".

Marsh met Johnson for the first time in May 1937. Marsh's secretary later recalled: "The first thing I noticed about Johnson was his availability. Whenever Marsh would ask Lyndon to come by for a drink, no matter that Lyndon was a busy man, he would always come. He was always available on short notice.... He was very deferential. Very, very deferential. I saw a young man who wanted to be on good terms with an older man, and was absolutely determined to be on good terms with him." Harold Young, one of Johnson's close friends, watched the young politician "play" many an older man. However, he felt that "he had never played one better than he did Charles Marsh".

The author of The Years of Lyndon Johnson: The Path to Power (1982) has argued: "Marsh liked to pontificate; Johnson drank in what he was saying, and told him how perceptive he was. Marsh liked to give advice; Johnson not only seemed to be accepting it, he asked for more. Marsh had become fascinated by politics; he wanted to feel he was on the inside of that exciting game. Johnson made him feel he was... His real political advisors - Wirtz, Corcoran - laughed at Marsh as an amateur.... He asked Marsh for advice on political strategy, asking him what he should say in speeches - let Marsh write speeches for him, and didn't let Marsh know that these speeches were not delivered."

During this period Johnson met Edward Clark, who worked for the Governor of Texas. The two men became close friends. Later, Clark became a lawyer in Austin and helped to guide Johnson's political career. Clark also introduced Johnson to important figures in the oil industry such as Clint Murchison and Haroldson L. Hunt. These men also helped to finance Johnson's political campaigns.

In July 1937 Charles Edward Marsh and his mistress, Alice Glass, visited the Saltzburg Music Festival. While they were in Europe they heard Adolf Hitler speak and saw the impact his policies were having on liberals and racial minorities. During their trip they met Jews who feared for their life. This included Max Graf, who was a professor at the Vienna Conservatory. Marsh told him he would do what he could to get him out of the country. It has been claimed that on the day when he was leaving the office for the last time, a colleague had given him the Nazi salute and said, "Heil, Hitler!". Graf replied "Heil, Beethoven!"

Marsh and Glass also met Erich Leinsdorf, a twenty-five-year-old musician. Leinsdorf later described how this "immensely rich" couple had offered to help him. In 1938 he arrived in the United States to take up a temporary position as assistant conductor at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City. When his term of employment came to an end he went to stay with them at Longlea. "It was a large farm, dominated by a magnificent house... with eighteen servants, over whom a German butler and his wife, a superlative cook, held sway."

Leinsdorf did not want to return to Nazi Germany and asked Marsh if he could help him to stay in the United States. The next day Marsh drove Leinsdorf to Washington where they stayed in his suite at the Mayflower Hotel. Leinsdorf explained in his autobiography, Cadenza: A Musical Career (1976), that Marsh summoned Johnson to the hotel: "A lanky young man appeared. He treated Charles with the informal courtesy behooving a youngster toward an older man to whom he is in debt." Johnson then arranged for Leinsdorf to become a "permanent resident" of the United States.

According to Jennet Conant: "Both Alice and Johnson took great pride in rescuing such a talented young musician. Leinsdorf had opened Johnson's eyes to the plight of refugees, and like Alice, who had been providing money to Jews fleeing Hitler, he began doing more on their behalf, eventually helping hundreds of Jewish refugees to reach safety in Texas through Cuba, Mexico, and other South American countries."

Lady Bird Johnson acknowledged the help that Charles Edward Marsh provided to her husband. She told Philip Kopper, the author of Anonymous Giver: A life of Charles E. Marsh (2000): "Charles Marsh had what I truly believe was an affectionate interest in enlarging Lyndon's life. He exuded what I can only describe as a life force - and even that is insufficient. He did a lot to educate Lyndon, and quite coincidentally me, about the breadth and strength of the rest of the world... This was when the war clouds were gathering in Europe and we did not know how to appraise Hitler - what it meant in the last term to the American people."

Marsh rewarded Johnson by helping him in his campaign to return to Congress. He gave instructions to Charles E. Green, editor of the Austin American-Statesman, to give Johnson help to be re-elected. On 30th January 1938, Green was doing such a good job he "ought... to be unopposed, and thus freed of the burden of a campaign, so as to give him his undivided time to his services in the session that will run almost until primary election day." On 5th May, 1938, the newspaper reported: "Johnson looks tired, but I suppose any man who has done as much for his district in the short time that Johnson has, should be tired. Fortunately, I don't think there's anyone in his district foolish enough to announce against him." During his campaign Johnson had promised that: "If the day ever comes when my vote was cast to send your boy to the trenches, that day Lyndon Johnson will leave his Senate seat and go with him."

Lyndon B. Johnson complained that he found it difficult managing on his Congress salary. Marsh arranged for Johnson's wife to buy nineteen acres on Lake Austin for $8,000, which he knew was an area that was likely to be developed and would increase dramatically in value. Lady Bird Johnson later sold the land for $330,000. He also provided the money for Johnson to buy the Fort Worth radio station that he said would be "some day worth $3 million". Marsh also offered Johnson the opportunity to buy some of his oil wells cheaply. Johnson declined the offer as he feared that this "could kill me politically". During the 1938 campaign, Marsh agreed to ask his business friends to contribute to the campaign. He eventually paid Johnson $5,000 a week. Mary Louise Glass, Marsh's private secretary, said it was her job to "keep track of who paid."

Johnson became a regular visitor to Marsh's home at Longlea. Marsh was often on business trips and Johnson developed a close relationship with Alice Glass. She told her sister Mary Louise, that Johnson had limitless potential: "She thought he was a young man who was going to save the world." She decided to help him become a successful politician. According to her sister, Alice taught him how to dress and how to eat food. She recommended the reading of books including the poetry of Edna St. Vincent Millay. Alice also advised him on how to be photographed. She told him that his left side was much better than his right. For the rest of his life "he would try to allow only the left side to be seen in photographs".

Frank C. Oltorf was a regular visitor to Longlea. He later recalled: "Alice Glass was the most elegant woman I ever met and Longlea was the most elegant home I ever stayed in." Arnold Genthe, who photographed the world's most attractive women for Vanity Fair, described Alice as the "most beautiful woman" he had ever met. He also considered Longlea as the "most beautiful place" he had ever seen and asked for his ashes to be scattered on the estate. Marsh's eldest daughter by his first marriage, Antoinette Marsh Haskell, did not like Alice: "She (Alice) took on the privileges of a great beauty, and was very self-serving and demanding. She was a real courtesan. She knew what she was doing."

Alice told her cousin, Alice Hopkins, the wife of the politician, Welly Kennon Hopkins, that by the end of 1938 that she and Johnson were lovers. Mrs. Hopkins later recalled: "They were unbelievably discreet and no one could have guessed that they were lovers. Nothing showed. Nothing at all." Alice also told her sister, Mary Louise, who had become one of Marsh's secretaries. Mary Louise claims that "Lyndon was the love of Alice's life. My sister was mad for Lyndon - absolutely mad for him." She later recalled that Marsh spent a lot of time away on business. It was during this time that Alice and Johnson were together at Longlea. When Marsh was at home Johnson often brought his wife, Lady Bird Johnson. She later told Philip Kopper, the author of Anonymous Giver: A life of Charles E. Marsh (2000), that Alice was "so tall and blonde" that she looked "like a Valkyrie". Lady Bird also admitted that "she helped educate Lyndon and me, particularly about music and a more elegant lifestyle than he and I spent our early days enjoying".

Alice Glass gave birth to two children while she was with Charles Edward Marsh but refused to marry him. Alice's sister, Mary Louise Glass, explained her unusual character: "She (Alice) was a free spirit - very independent - in an era when women weren't that way... Above everything else, Alice was an idealist... She had a very particular view of the kind of place the world should be and she was willing to do anything she had to do to make things come out right for people who were in trouble." According to Mary Louise, Alice wanted to marry Johnson. He was in a difficult position as in the 1930s a divorced man would be effectively barred from a political career. Johnson considered taking up a job as a corporate lobbyist in Washington. Alice rejected this idea as she considered he had the potential to become president of the United States.

On 4th April, 1941, Texas senator, Morris Sheppard died. Tommy Corcoran agreed to help Johnson in his campaign to replace Sheppard. This included helping Johnson obtain approval of a rural electrification project from the Rural Electrification Administration. Corcoran also arranged to Franklin D. Roosevelt to make a speech on the eve of the polls criticizing Johnson's opponent, Wilbert Lee O'Daniel. Despite the efforts of Corcoran, O'Daniel defeated Johnson by 1,311 votes.

On the suggestion of Alvin J. Wirtz, Johnson decided to acquire KTBC, a radio station in Austin. E. G. Kingsberry and Wesley West, agreed to sell KTBC to Johnson (officially it was purchased by his wife, Lady Bird Johnson). However, it needed the approval of the Federal Communications Commission (FCR). Johnson asked Tommy Corcoran for help with this matter. This was not very difficult as the chairman of the FCR, James Fly, was appointed by Frank Murphy as a favour for Corcoran. The FCC eventually approved the deal and Johnson was able to use KTBC to amass a fortune of more than $25 million.

Johnson kept his pledge made during the 1937 election and when the United States entered the Second World War in December, 1941, Johnson immediately joined the United States Navy. Commissioned as a Lieutenant Commander, he served in the South Pacific.

In 1948, Johnson decided to make a second run for the U.S. Senate. His main opponent in the Democratic primary (Texas was virtually a one party state and the most important elections were those that decided who would be the Democratic Party candidate) was Coke Stevenson. Johnson was criticized by Stevenson for supporting the Taft-Hartley Act. The American Federation of Labor was also angry with Johnson for supporting this legislation and at its June convention the AFL broke a 54 year tradition of neutrality and endorsed Stevenson.

Johnson asked Tommy Corcoran to work behind the scenes at convincing union leaders that he was more pro-labor than Coke Stevenson. This he did and on 11th August, 1948, Corcoran told Harold Ickes that he had "a terrible time straightening out labor" in the Johnson campaign but he believed he had sorted the problem out.

On 2nd September, unofficial results had Coke Stevenson winning by 362 votes. However, by the time the results became official, Johnson was declared the winner by 17 votes. Stevenson immediately claimed that he was a victim of election fraud. On 24th September, Judge T. Whitfield Davidson, invalidated the results of the election and set a trial date.

A meeting was held that was attended by Tommy Corcoran, Francis Biddle, Abe Fortas, Joe Rauh, Benjamin Cohen and Jim Rowe. It was decided to take the case directly to the Supreme Court. A motion was drafted and sent to Justice Hugo Black. On 28th September, Justice Black issued an order that put Johnson's name back on the ballot. Later, it was claimed by Rauh that Black made the decision following a meeting with Corcoran.

On 2nd November, 1948, Johnson easily defeated Jack Porter, his Republican Party candidate. Coke Stevenson now appealed to the subcommittee on elections and privileges of the Senate Rules and Administration Committee. Corcoran enjoyed a good relationship with Senator Styles Bridges of New Hampshire. He was able to work behind the scenes to make sure that the ruling did not go against Johnson. Corcoran later told Johnson that he would have to repay Bridges for what he had done for him regarding the election.

The Johnson-Stevenson case was also investigated by J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI. Johnson was eventually cleared by Hoover of corruption and was allowed to take his seat in the Senate. Johnson soon emerged as an important member of the Senate. Although he had been seen as a progressive with his support for the New Deal, he had conservative views on civil rights. He voted against an anti-lynching bill and during the 1940s and 1950s he opposed all attempts to pass civil rights legislation.

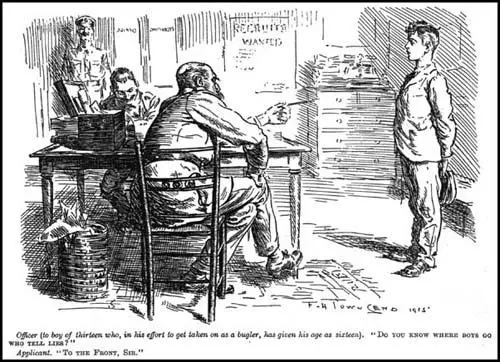

On this day in 1914 16-year-old George Coppard joins the British Army. "Although I seldom saw a newspaper, I knew about the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand at Sarajevo. News placards screamed out at every street corner, and military bands blared out their martial music in the main streets of Croydon. This was too much for me to resist, and as if drawn by a magnate, I knew I had to enlist straight away. I presented myself to the recruiting sergeant at Mitcham Road Barracks, Croydon. There was a steady stream of men, mostly working types, queuing to enlist. The sergeant asked me my age, and when told, replied, 'Clear off son. Come back tomorrow and see if you're nineteen, eh?' So I turned up again the next day and gave my age as nineteen. I attested in a batch of a dozen others and, holding up my right hand, swore to fight for King and Country. The sergeant winked as he gave me the King's shilling, plus one shilling and ninepence ration money for that day."

Hundreds of boys falsified birth dates to meet the minimum age requirements. Desperate for soldiers, recruiting officers did not always check the boy's details very carefully. A sixteen year-old later told of how he was able to join the army: "The recruiting sergeant asked me my age and when I told him he said, 'You had better go out, come in again, and tell me different.' I came back, told him I was nineteen and I was in." Private E. Lugg was able to join the 13th Royal Sussex Regiment at the age of thirteen. 1915."

However, he was not the youngest soldier in the British Army, Private Lewis served at the Somme when he was only twelve. George Maher, who was only 13 at the time, claims that Lewis was too short to see over the edge of the trench."The youngest was 12 years old. A little nuggety bloke he was, too. We joked that the other soldiers would have had to have lifted him up to see over the trenches." Maher was eventually arrested: "I was locked up on a train under guard, one of five under-age boys caught serving on the front being sent back to England."

boys go who tell lies?" Applicant: "To the Front, Sir."

F. H. Townsend, Punch Magazine (11th August, 1916)

On this day in 1919 Winston Churchill orders the dropping chemical weapons on the Russian village of Emtsa. Churchill had supported the sending of British troops to help the White Army in the Russian Civil War, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel John Ward. However, it had not been a success Ward later told one of his officers, Brian Horrocks: "I believe we shall rue this business for many years. It is always unwise to intervene in the domestic affairs of any country. In my opinion the Reds are bound to win and our present policy will cause bitterness between us for a long time to come." Horrocks agreed: "How right he was: there are many people today who trace the present international impasse back to that fatal year of 1919."

Churchill argued that the British had not sent enough troops. He argued in a Cabinet meeting that Britain should intervene "thoroughly, with large forces, abundantly supplied with mechanical appliances". He also suggested a campaign to recruit a volunteer army to fight in Russia. David Lloyd George admitted that the Cabinet was united in its hostility to the Bolsheviks but they did have support in Russia. He added that Britain had no right to interfere in their internal affairs and anyway lacked the means to do so.

Winston Churchill now took the controversial decision to use the stockpiles of M Device against the Red Army. He was supported in this by Sir Keith Price, the head of the chemical warfare, at Porton Down. He declared it to be the "right medicine for the Bolshevist" and the terrain would enable it to "drift along very nicely". Price agreed with Churchill that the use of chemical weapons would lead to a rapid collapse of the Bolshevik government in Russia: "I believe if you got home only once with the Gas you would find no more Bolshies this side of Vologda."

In the greatest secrecy, 50,000 M Devices were shipped to Archangel, along with the weaponry required to fire them. Winston Churchill sent a message to Major-General William Ironside: "Fullest use is now to be made of gas shell with your forces, or supplied by us to White Russian forces." He told Ironside that this "thermogenerator of arsenical dust that would penetrate all known types of protective mask". Churchill added that he would very much like the "Bolsheviks" to have it. Churchill also arranged for 10,000 respirators for the British troops and twenty-five specialist gas officers to use the equipment.

Some one leaked this information and Winston Churchill was forced to answer questions on the subject in the House of Commons on 29th May 1919. Churchill insisted that it was the Red Army who was using chemical warfare: "I do not understand why, if they use poison gas, they should object to having it used against them. It is a very right and proper thing to employ poison gas against them." His statement was untrue. There is no evidence of Bolshevik forces using gas against British troops and it was Churchill himself who had authorised its initial use some six weeks earlier.

On 27th August, 1919, British Airco DH.9 bombers dropped these gas bombs on the Russian village of Emtsa. According to one source: "Bolsheviks soldiers fled as the green gas spread. Those who could not escape, vomited blood before losing consciousness." Other villages targeted included Chunova, Vikhtova, Pocha, Chorga, Tavoigor and Zapolki. During this period 506 gas bombs were dropped on the Russians. Lieutenant Donald Grantham interviewed Bolshevik prisoners about these attacks. One man named Boctroff said the soldiers "did not know what the cloud was and ran into it and some were overpowered in the cloud and died there; the others staggered about for a short time and then fell down and died". Boctroff claimed that twenty-five of his comrades had been killed during the attack. Boctroff was able to avoid the main "gas cloud" but he was very ill for 24 hours and suffered from "giddiness in head, running from ears, bled from nose and cough with blood, eyes watered and difficulty in breathing."

Major-General William Ironside told David Lloyd George that he was convinced that even after these gas attacks his troops would not be able to advance very far. He also warned that the White Army had experienced a series of mutinies (there were some in the British forces too). Lloyd George agreed that Ironside should withdraw his troops. This was completed by October. The remaining chemical weapons were considered to be too dangerous to be sent back to Britain and therefore it was decided to dump them into the White Sea.

Winston Churchill created great controversy by the creation of Iraq. According to Boris Johnson: "He (Churchill) was the man who decided that there should be such a thing as the state of Iraq, if you wanted to blame anyone for the current implosion, then of course you might point the finger at George W. Bush and Tony Blair and Saddam Hussein - but if you wanted to grasp the essence of the problem of that wretched state, you would have to look at the role of Winston Churchill."

On this day in 1931 Frank Harris died of heart failure.

James Thomas (Frank) Harris, the third son and fourth of the five children of Thomas Vernon Harris (1814–1899), a mariner, and his wife, Anne (1816–1859), was probably born on 14th February 1856, in Galway. According to his biographer, Richard Davenport-Hines: "He endured a mean, miserable, and loveless childhood, in which he resented alike the puritanical severity of his father and the discipline of his masters at the Royal School in Armagh and, later, Ruabon Grammar School in Denbighshire (1869–71)"

Harris wrote about his time at Ruabon Grammar School in his autobiography, My Life and Loves (1922): "The English are proud of the fact that they hand a good deal of the school discipline to the older boys: they attribute this innovation to Arnold of Rugby and, of course, it is possible, if the supervision is kept up by a genius, that it may work for good and not for evil; but usually it turns the school into a forcing-house of cruelty and immorality. The older boys establish the legend that only sneaks would tell anything to the masters, and they are free to give rein to their basest instincts."

Harris emigrated to the United States in 1871 and went to live with his brother in Lawrence, Kansas. He enrolled at the University of Kansas in 1874 and passed the Douglas County bar examinations in 1875. He then moved to Brighton and became a French tutor at Brighton College. Harris married Florence Ruth (1852–1879) in Paris, on 17th October 1878. On her death of tuberculosis ten months later, he moved to London where he attempted to make a living from journalism. He joined the Social Democratic Federation where he made contact with H. M. Hyndman, Tom Mann, John Burns, Eleanor Marx, George Lansbury, Edward Aveling, H. H. Champion, Guy Aldred, Dora Montefiore, Clara Codd, John Spargo and Ben Tillett.

In 1883 he was appointed editor of The London Evening News. By this time he had left the SDF but the newspaper did run several campaigns against poverty. Harris developed a reputation as being hostile to the aristocracy with his emphasis on society scandals. Michael Holroyd pointed out: "He (Harris) quadrupled its circulation by sending his journalists to the police courts, and startling his readers with alluring headlines, 'Extraordinary Charge Against a Clergyman and Gross Outrage on a Female'. It was Harris who had reported in scabrous detail the divorce case of Lady Colin Campbell, receiving an indictment for obscene libel that assisted the paper's Tory proprietor in dismissing him in 1886." Soon afterwards he became the editor of The Fortnightly Review.

Frank Harris married Emily Clayton on 2nd November 1887. She was the widow of Thomas Greenwood Clayton, a successful businessman. He intended to use her fortune of £90,000 to launch his political career. He joined the Conservative Party and became the prospective candidate in South Hackney. However, he withdrew his candidature in 1891, after supporting Charles Stewart Parnell in the O'Shea divorce. Harris was a well-known womaniser and his wife left him in 1894.

Harris appointed George Bernard Shaw and Max Beerbohm as drama critics for The Fortnightly Review. He also published long articles by Shaw (Socialism and Superior Brains) and Oscar Wilde (The Soul of Man Under Socialism) about socialism. Harris also continued to campaign against the aristocracy and financial corruption. This made him many enemies and in 1894 he was sacked by Frederick Chapman, the owner of the journal, for publishing an article by Charles Malato, an anarchist who praised political murder as "propaganda… by deed".

Harris now purchased The Saturday Review. The author, H.G. Wells, got to know him during this period: "His dominating way in conversation startled, amused and then irritated people. That was what he lived for, talking, writing that was loud talk in ink, and editing. He was a brilliant editor, for a time, and then the impetus gave out, and he flagged rapidly. So soon as he ceased to work vehemently he became unable to work. He could not attend to things without excitement. As his confidence went, he became clumsily loud."

Once again he appointed George Bernard Shaw as his drama critic on a salary of £6 a week. Shaw later commented that was "not bad pay in those days" and added that Harris was "the very man for me, and I the very man for him". Shaw's hostile reviews led to some managements withdrawing their free seats. Some of the book reviewers were so severe that publishers cancelled their advertisements. Harris was forced to sell the journal for financial reasons in 1898. Michael Holroyd has argued: "There had been a number of libel cases and rumours of blackmail - later put down by Shaw to Harris's innocence of English business methods."

Margot Asquith and Herbert Henry Asquith also met him at this time. Margot recalled in her autobiography: "He sat like a prince - with his sphinx-like imperviousness to bores - courteous and concentrated on the languishing conversation. I made a few gallant efforts; and my husband, who is particularly good on these self-conscious occasions, did his best... but to no purpose."

According to his biographer, Richard Davenport-Hines, Harris had a complicated sex life: "In 1898 Harris was maintaining a ménage at St Cloud with an actress named May Congden, with whom he had a daughter, together with a house at Roehampton containing Nellie O'Hara, with whom he possibly also had a daughter (who died young). He seems to have had other daughters with different women. O'Hara was his helpmate and âme damnée for over thirty years. Apparently the natural daughter of Mary Mackay and a drunkard named Patrick O'Hara, she was a clumsy schemer, battening onto Harris in the hope of millions but encouraging him in self-destructive and rascally courses."

Frank Harris became friends with several leading literary figures, including George Meredith, Oscar Wilde and Walter Pater. In his autobiography, My Life and Loves (1922), Harris recalled that: "One day in 1890 I had George Meredith, Walter Pater and Oscar Wilde dining with me in Park Lane and the time of sex-awakening was discussed. Both Pater and Wilde spoke of it as a sign of puberty. Pater thought it began about thirteen or fourteen and Wilde to my amazement set it as late as sixteen. Meredith alone was inclined to put it earlier."

In 1900 Frank Harris had a book of short stories, Montes the Matador, published. Later that year, his first play, Mr and Mrs Daventry, was produced. The play, that dealt with adultery and sexually emancipated women, was described by Gerald du Maurier, as "the most daring and naturalistic production of the modern English stage… at once repellent and fantastic". His novel, The Bomb, about anarchism set in Chicago, appeared in 1908. The reviewer in the Times Literary Supplement called it a "highly charged with an explosive blend of socialistic and anarchistic matter, wrapped in a gruesome coating of exciting fiction… crowded with swindled workmen, callous employers, brutal police, inhuman millionaires". This was followed by three works about William Shakespeare, entitled The Man Shakespeare (1909), Shakespeare and his Love (1910) and The Women of Shakespeare (1911).

In August 1913, Harris began a magazine entitled, Modern Society. He employed Enid Bagnold as a staff writer. She later recalled: "He was an extraordinary man. He had an appetite for great things and could transmit the sense of them. He was more like a great actor than a man of heart. He could simulate anything. While he felt admiration he could act it, and while he acted it, he felt it. And greatness being his big part, he hunted the centuries for it, spotting it in literature, in passion, in action." She added: "His theory was that women love ugly men. He made sin seem glorious. He was surrounded by rascals. It was better than meeting good men. The wicked have such glamour for the young."

In Bagnold's Autobiography (1917) she admitted that Harris took her virginity. "The great and terrible step was taken... I went through the gateway in an upper room in the Cafe Royal. That afternoon at the end of the session I walked back to Uncle Lexy's at Warrington Crescent, reflecting on my rise. Like a corporal made sergeant.... And what about love - what about the heart? It wasn't involved. I went through this adventure like a boy, in a merry sort of way, without troubling much. I didn't know him. If I had really known him I might have been tender." During dinner with Uncle Lexy she later wrote that she couldn't believe that her skull wasn't chanting aloud: "I'm not a virgin! I'm not a virgin".

In February 1914 Harris was sent to Brixton Prison for contempt of court following an article on Earl Fitzwilliam, who had been cited as a co-respondent in a divorce case. On his release he moved to New York City. In 1915 he published Contemporary Portraits. The following year he published a biography of Oscar Wilde. Harris also wrote extensively about the First World War. He was highly critical of the way the war was being fought and some of these were described as "traitorious". He also predicted that Germany would win the war. These articles appeared as England or Germany? (1915). In 1916 he became editor of Pearson's Magazine. According to his biographer, Richard Davenport-Hines: "He (Harris) repeatedly clashed with American censorship and made many enemies with his rude, unpredictable, and arrogant conduct."

Harris now moved to Nice. After the death of his second wife he married Nellie O'Hara. Harris's response to becoming sexually impotent was to write an autobiography about his sex life. Harris told George Bernard Shaw: "I am going to see if a man can tell the truth naked and unashamed about himself and his amorous adventures in the world." The first volume of My Life and Loves was published in 1922. The first volume was burnt by customs officials and the second volume resulted in him being charged with corrupting public morals.

In 1928 Harris wrote to Shaw asking if he could write his biography. Shaw replied: "Abstain from such a desperate enterprise... I will not have you write my life on any terms." Harris was convinced that the royalties of the proposed book would solve his financial problems. In 1929 he wrote: "You are honoured and famous and rich - I lie here crippled and condemned and poor."

Eventually, George Bernard Shaw agreed to cooperate with Harris in order to help him provide for his wife. Shaw told a friend that he had to agree because "Frank and Nellie... were in rather desperate circumstances." Shaw warned Harris: "The truth is I have a horror of biographers... If there is one expression in this book of yours that cannot be read at a confirmation class, you are lost for ever. " He sent Harris contradictory accounts of his life. He told Harris that he was "a born philanderer". On another occasion he attempted to explain why he had little experience of sexual relationships. In 1930 he wrote to Harris: "If you have any doubts as to my normal virility, dismiss them from your mind. I was not impotent; I was not sterile; I was not homosexual; and I was extremely susceptible, though not promiscuously."

Frank Harris died of heart failure on 26th August 1931. Shaw sent Nellie a cheque and she arranged to send him the galley-proofs. The book was then rewritten by Shaw: "I have had to fill in the prosaic facts in Frank's best style, and fit them to his comments as best I could; for I have most scrupulously preserved all his sallies at my expense.... You may, however, depend on it that the book is not any the worse for my doctoring." George Bernard Shaw was published in 1932.

On this day in 1969 Erika Mann, suffering from a brian tumour, died in Zürich, aged 63.

Erika Mann, the daughter of the novelist, Thomas Mann, was born in Munich on 9th November, 1905. Her mother, Katia Pringsheim Mann, was the daughter of a wealthy, Jewish industrialist family who owned coal mines and early railroads.

Soon after Erika was born, her father wrote to his brother, Heinrich Mann about his new child: "Unexpectedly, the birth was frightfully difficult, and my poor Katia had to suffer so cruelly that the whole thing became an almost unendurable horror. I shall not forget this day for the rest of my days. I had a notion of life and one of death, but I did not yet know what birth is. Now I know that it is as profound a matter as the other two.... The little girl, who will be named Erika at her mother's wish, promises to be very pretty. For brief moments I think I see just a little Jewishness showing through, and every time that happens it greatly amuses me."

It is claimed that the parents were disappointed that their first child was a girl. The next year a son, Klaus Mann, was born, therefore guaranteeing the Mann dynastic name. Erika and Klaus looked so much alike and were so emotionally close, they were known as "the twins". They both dressed similarly and celebrated their birthdays on the same date." They were followed by Gottfried (1909), Monika (1910), Elisabeth (1918) and Michael (1919).

Although her mother came from a Jewish family, all the six children were baptised as Protestants. According to Mann's biographer, Anthony Heilbut, she was his favourite. The Mann were considered to be very unconventional: "Mann had tainted his new family with scandal. It would trail him for years; literary gossip recounted how Katia strolled hand-in-hand with her brother Klaus; while the Mann's oldest children, Erika and Klaus, had a penchant for shared wardrobes."

Erika Mann attended a private school with her brother. In May 1921, she transferred to the Luisengymnasium in Munich. With a group of friends, Erika and Klaus, they founded an experimental theater troupe, the Laienbund Deutscher Mimiker. In 1924 she began her theatrical studies in Berlin and during this period she worked under Max Reinhardt and appeared in several productions.

In 1924, Klaus Mann wrote Anja and Esther, a play about "a neurotic quartet of four boys and girls" who "were madly in love with each other". The following year he was approached by the actor Gustaf Gründgens, who wanted to direct the play with himself in one of the male roles, Klaus in the other; Erika Mann and Pamela Wedekind, the daughter of the playwright Frank Wedekind, would be the two young women. "Klaus planned to marry Pamela, with whom Erika fell in love, while Erika arranged to marry Gustaf, with whom Klaus began an affair."

The play, which opened in Hamburg in October 1925, attracted vast amounts of publicity, partly because of its scandalous content and partly because it starred three children of two famous writers. A photograph appeared on the cover of Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung. It created a great deal of controversy as "Klaus's lipstick gave him the look of a transvestite".

It has been argued that Thomas Mann was also bi-sexual and as a young man he had a sexual relationship with Ernst Bertram. One of his biographer's, Richard Winston, has claimed: "Never in his whole life was he to admit openly to that defect, except in the deep privacy of his diaries. Yet he nursed this secret as a source of pleasure, of interest, of creative power."

The Mann family lived in luxury. Gottfried later wrote, "thanks to the Nobel Prize and the tremendous earnings of The Magic Mountain. They took trips, they ate and drank well, and two large cars stood in the garage: an open American car and a German limousine. When they went to the theatre, the chauffeur waited in the lobby with their fur coats at the end of the performance. This style of life, which they went to no trouble to conceal, made their growing number of political enemies hate them all the more".

On 24th July, 1926, Erika married Gustaf Gründgens, but the marriage was not successful and they lived together for a short period. (10) In 1927, she and Klaus traveled around the world. On her return to Germany she divorced Gründgens, who was sympathetic to the Nazi Party. She began a passionate affair with Pamela Wedekind, who at that time was engaged to her brother, Klaus Mann. Erika also had a relationship with the actress Therese Giehse, and appeared in the film about lesbianism Mädchen in Uniform (1931). It was a great success but because of its subject matter it was banned in the United States.

Colm Tóibín has pointed out that during this period Erika and Klaus "wrote articles and books and made outrageous statements; they travelled, they had many lovers. Erika worked in the theatre and appeared in films, Klaus wrote more plays. In other words, they took full advantage of the freedoms offered by the Weimar Republic. For many in the Nazi Party, they were the epitome of all that was wrong with Germany. And their mother’s Jewish background didn’t endear them to the National Socialists either."

Hermann Kurzke has suggested: "Professionally, her focus shifted from the stage to journalism. A journey to Africa in 1930 introduced experiences with drugs. Erika trained as an automobile mechanic and in 1931 participated in a rally, driving ten thousand kilometers in ten days."

In January 1932, Erika Mann was asked to read a poem by Victor Hugo to a women’s pacifist group. However, a group of Sturmabteilung (SA) men were in the audience and they heckled her. One of them shouted out: "You are a criminal... Jewish traitress! International agitator!" She later wrote: "In the hall, everything became a mad scramble. The Stormtroopers attacked the audience with their chairs, shouting themselves into paroxysms of anger and fury." The Nazi newspaper, Völkischer Beobachter, reported that Mann was "a flatfooted peace hyena" with "no human physiognomy". Mann sued for damages and after examining several photographs of her the judge declared that her face was in fact legally human."

Mann now became heavily involved in politics. "I realised that my experience had nothing to do with politics - it was more than politics. It touched at the very foundation of my - of our - of the existence of all." Mann joined together with a group of left-wing activists, including Therese Giehse, Walter Mehring, Magnus Henning, Wolfgang Koeppen and Lotte Goslar, to establish a cabaret in Munich called Die Pfeffermühle (The Peppermill).

The production opened on 1st January, 1933. Erika Mann wrote most of the material, much of which was anti-Fascist. It ran for two months next door to the local Nazi headquarters, and, since it was so successful, was preparing to move to a larger theatre when the Reichstag went up in flames. Erika and Klaus were on a skiing holiday while the new theatre was being decorated and arrived back in Munich to be warned by the family chauffeur, that they were in danger. Later, Klaus wrote that the chauffeur "had been a Nazi spy throughout the four or five years he lived with us... But this time he had failed in his duty, out of sympathy, I suppose. For he knew what would happen to us if he informed his Nazi employers of our arrival in town."

Adolf Hitler gained power in January 1933. Soon afterwards, a large number of writers were declared to be "degenerate authors". This included Heinrich Mann, Bertolt Brecht, Hans Eisler, Ernst Toller, Thomas Heine, Arnold Zweig, Ludwig Renn, Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud, Franz Kafka and Hermann Hesse. On 10th May, the Nazi Party arranged the burning of thousands of "degenerate literary works" were burnt in German cities.

However, Thomas Mann's work still remained popular in Germany and unlike his brother, Heinrich, had made no statements attacking the regime. His biographer, Hermann Kurzke, has argued that during the period before he took power, Mann developed friendships with some significant figures in the Nazi Party: "Does that make Thomas Mann a precursor of Fascism? He certainly made an effort to stay out of the way of the resurgent right-wing movement of the time. Very early on in the summer of 1921, he took note of the rising Nazi movement and dismissed it as ‘swastika nonsense’. As early as 1925 when Hitler was still imprisoned in Landsberg, he rejected the cultural barbarity of German Fascism with an extensive, decisive and clearly visible gesture." However, others had pointed out, he had always been careful not to attack Hitler in print.

Thomas Mann was on holiday in France when Hitler took power. Erika and Klaus were warned by the family chauffeur that the Mann family were in danger. (21) Later, Klaus wrote that the chauffeur "had been a Nazi spy throughout the four or five years he lived with us... But this time he had failed in his duty, out of sympathy, I suppose. For he knew what would happen to us if he informed his Nazi employers of our arrival in town."

Erika made contact with her parents, and warned them not to return to Munich. Mann, who was on holiday at the time, was warned that he faced the possibility of being arrested if he returned to Germany. In September, 1933, Thomas, Katia, Gottfried, Monika, Elisabeth and Michael Mann settled in Küsnacht, near Zurich. Erika and Klaus decided to remain in Germany to continue the fight against fascism.

In April 1933, Thomas Mann wrote in his diary, that he had finally accepted that "something deeply significant and revolutionary be taking place in Germany? The Jews: it is no calamity after all... that the domination of the legal system by the Jews has been ended. Secret, disquieting, persistent musings... I am beginning to suspect that in spite of everything this process is one of those that has two sides to them".

During the period Erika worked as a journalist. She later wrote that "the life of every human being in Germany has been fundamentally changed since Adolf Hitler became Chancellor.... German democracy gave way to Nazi dictatorship, the upheaval was as drastic to the private life of the individual as it was to the State." Before Hitler came to power "the German citizen thought of himself as a father, or a Protestant, or a florist, or a citizen of the world, or a pacifist, or a Berliner. Now he is forced to recognise that above all he is a National Socialist."

Erika Mann was especially interested in the impact of Nazi ideology on children. "All the power of the regime - all its cunning, its entire machine of propaganda and discipline - is directed to emphasize the program for German children. It is not surprising that the Nazi State considers it of primary importance that the young grow up according to Hitler's wishes, and the plans set in Mein Kampf... The Führer realizes that the education of German youth will have a tremendous influence on Germany's future - and on Europe's and the world's. He gives the problem the attention it deserves."

Mann quotes Hitler as saying in Mein Kampf (1925): "Beginning with the primer, every theater, every movie, every advertisement must be subjected to the service of one great mission, until the prayer of fear that our patriots pray today: Lord, make us free, shall be changed in the mind of the smallest child into the cry: Lord, do Thou in future bless our arms... All education must have the sole object of stamping the conviction into the child that his own people and his own race are superior to all others."

In her book, School for Barbarians, Mann argues that the Weimar Republic made a serious mistake to create a political neutral curriculum. "One subject, political propaganda, was missing from the curriculum. The German Republic refused to influence its citizens one way or the other, or to convince them of the advantages of democracy; it did not carry on any propaganda in its own favour. This proves to have been an error... Unused to self-rule, the German people submitted to a new State which made itself the master, and forced the people to be its servants."

Mann reported that "in the winter of 1933, was that all teachers of non-Aryan or Jewish descent were relieved of their posts. An edict was issued on July 11, 1933, that included teachers with all other State officials, ordering them to subordinate their wishes, interests, and demands to the common cause, to devote themselves to the study of National Socialist ideology, and 'suggesting' that they familiarize themselves with Mein Kampf. Three days later, a 'suggestion' was sent to all those who still maintained contact with the Social Democratic Party, that they inform the Nazi Party of the severance of these connections. Committees were formed to see that it was carried out, and whoever hesitated was instantly dismissed. The purge was on. It was decided, in Prussia first (November, 1933), and later in all German schools, that public school teachers must belong to a Nazi fighting organization; they were to come to school in uniform, wherever possible, and live in camps; and, during the final examinations, they were to be tested in military sports."

Erika Mann remained in constant danger. Her friends told her that one way she could protect herself was to marry a foreigner. In 1935, the poet W.H. Auden, who was an homosexual, offered to marry her. She agreed and visited England for the ceremony in Colwall. When the German government heard what she had done, she was stripped of her German citizenship. According to Time Magazine, "at the risk of her life, she returned secretly to Germany to get some of her father's manuscripts."

Thomas Mann remained silent on the Nazi crimes and continued to be published in Germany. In 1936, Mann's publisher, Gottfried Bermann Fischer, was denounced by exiles as a Jewish protégé of Joseph Goebbels . Mann responded by making a fervent public defence of Bermann. Erika was appalled wrote to her father: "You are stabbing in the back the entire émigré movement - I can put it no other way. Probably you will be very angry at me because of this letter. I am prepared for that, and I know what I’m doing. This friendly time is predestined to separate people – in how many cases has it happened already. Your relation to Dr Bermann and his publishing house is indestructible – you seem to be ready to sacrifice everything for it. In that case it is a sacrifice for you that I, slowly but surely, will be lost for you – then just never mind. For me it is sad, and terrible. I am your child."

Erika Mann joined the anti-fascist American Artists' Congress (AAC), a group closely associated with the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA). Other members included Rockwell Kent, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, William Gropper, Max Weber, George Biddle, William Zorach, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Philip Evergood, Nathaniel Dirk, Arnold Blanch, Victor Candell, Mervin Jules and Alexander Z. Kruse.

Erika eventually convinced her father to become active in America's anti-fascist movement. In December 1937, she attended a meeting of 400 members of the AAC at Carnegie Hall where she read out a statement from Thomas Mann: "One frequently hears it said that the artist should stick to his own craft, and that he merely cheapens himself when he descends into the political arena to participate in the struggles of the day. I consider this a weak objection, because of my conviction, or rather my clear realization, of the fact that the different spheres of humanity - whether artistic, cultural or political - are really inseparable. And that is why it makes me very happy to see that the art world of a country as large and as important to civilization as the United States... is taking its stand against those barbaric tendencies which today endanger all that we understand by civilization and culture and all that we love."

While living in the United States she began an affair with a German doctor, Martin Gumpert, who was staying at her hotel. Gumpert wanted to maary her but she refused. According to Sybille Bedford, she "went off women, she really became interested in men, she went off with people’s husbands even." Erika told Bedford: "I fancy almost all of them, porters, liftboys, and so on, white or black. Almost all are agreeable to me. I could sleep with all of them."

In 1938, Erika and Klaus reported on the Spanish Civil War. On her return she published, School for Barbarians, a book on the Nazi education system; it sold forty thousand copies in the US in the first three months after publication. Time Magazine commented: "Miss Mann's book is about Germany's children. Other investigators have reported what has happened under the Nazis to Germany's once-great educational system but none has reported so scathingly as Erika Mann what has happened to Germany's youngsters."

The FBI kept a close watch on Erika Mann as she was suspected of being a secret supporter of the Communist Party of the United States. The FBI snoopers speculated that Erika may have had a sexual relationship with her brother, Klaus. "Confidential informants" told agents that the two were having an affair, one file reports. Erika Mann was described in the files as having her hair cut "in a short mannish bob with a part on the right side" and to be close to a group of political actors who were "members of the Hebrew race". In 1940 Erika agreed to work with the FBI and gave information on members of the German exile community, who she suspected of pro-Nazi connections. (37) Erika once claimed that "she was neither a Jew or a Communist".

Soon after the outbreak of the Second World War, Klaus and Erika Mann published The Other Germany (1940). In the book they argued: "Germany's structure... is regional. The Germans do not care to, and do not actually, accept dictation from Berlin. There are, moreover, simply too many Germans in Europe for one state. An empire comprising all Germans would always constitute an implied threat and a source of unrest for the Continent... The land of Europe's middle, the mediator between North and South, East and West, has no mission to rule, but the more profound and noble mission to unite and reconcile." Erica Mann also reported on the war in Europe for Liberty Magazine.

One reviewer claimed: "The Manns are weak on analysis of the tremendous economic problem that will arise if the totalitarian state is defeated. But their book is a strong and pertinent reminder of the cultural resilience and political talent Germany displayed under the Weimar Republic (whose constitution was as liberal a one as Europe had ever seen). If Europe after World War II is to be federal, as they hope, the Manns provide a logical line on the neglected question as to what sort of Germany should take part in the federation."

Erika Mann returned to Germany a few weeks after the end of the Second World War. She later wrote: "The Germans, as you know, are hopeless. In their hearts, self-deception and dishonesty, arrogance and docility, shrewdness and stupidity are repulsively mingled and combined. " Sybille Bedford said of her: "Erika could hate, and she hated the Germans. You see, Erika was a fairly violent character. At one point during the war, she propagated that every German should be castrated.... Erika was very unforgiving."

Erika Mann was the only woman to cover the Nuremberg War Trials. This included an interview with Julius Streicher. In 1946 Erika went to live with her father after he had been diagnosed with lung cancer and was being operated on in Chicago. For the next nine years she was Mann’s secretary and chief confidante. Elisabeth Mann remembered: "She returned home, because she had exhausted her career, and so devoted herself to the work of her father... Erika was a very powerful personality, a very dominant, domineering personality, and I must say that this role that she played in the latter part of her life as manager of my father was not always very easy to take for my mother, because she had been used to doing all of that."

Erika Mann returned with her parents to the US and sought citizenship only to find that she was once more under investigation by the FBI. So were her friends such as Hans Eisler and Bertolt Brecht were ordered to appear before the Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Eisler and Brecht both decided to leave the country. Mann described the behaviour of members of the HUAC such as John Rankin and J. Parnell Thomas as "fascistic". In his diary he wrote: "What oath would Congressman Rankin or Thomas take if forced to swear that they hated fascism as much as Communism?"

Brecht told the HUAC: "As a guest of the United States, I refrained from political activities concerning this country even in a literary form. By the way, I am not a screen writer, Hollywood used only one story of mine for a picture showing the Nazi savageries in Prague. I am not aware of any influence which I could have exercised in the movie industry whether political or artistic. Being called before the Un-American Activities Committee, however, I feel free for the first time to say a few words about American matters: looking back at my experiences as a playwright and a poet in the Europe of the last two decades, I wish to say that the great American people would lose much and risk much if they allowed anybody to restrict free competition of ideas in cultural fields, or to interfere with art which must be free in order to be art. We are living in a dangerous world. Our state of civilization is such that mankind already is capable of becoming enormously wealthy but, as a whole, is still poverty-ridden. Great wars have been suffered, greater ones are imminent, we are told. One of them might well wipe out mankind, as a whole. We might be the last generation of the specimen man on this earth. The ideas about how to make use of the new capabilities of production have not been developed much since the days when the horse had to do what man could not do. Do you not think that, in such a predicament, every new idea should be examined carefully and freely? Art can present clear and even make nobler such ideas."

The first ten men accused of being communists: Alvah Bessie, Herbert Biberman, Albert Maltz, Adrian Scott, Samuel Ornitz, Dalton Trumbo, Lester Cole, Edward Dmytryk, John Howard Lawson and Ring Lardner Jr, refused to answer any questions about their political and union activities. Known as the Hollywood Ten, they claimed that the 1st Amendment of the United States Constitution gave them the right to do this. The HUAC and the courts during appeals disagreed and all were found guilty of contempt of Congress and each was sentenced to between six and twelve months in prison.

On hearing the news, Thomas Mann issued a statement comparing the activities of the HUAC with those of Nazi Germany: "As an American citizen of German birth and one who has been through it all, I deem it not only my right but my solemn duty to state: We - the America of the Un-American Activities Committee; the America of the so-called loyalty checks... are well on our way towards the fascist police state and - hence - well on our way towards war."

Klaus Mann made several attempts to kill himself. While in Los Angeles in 1948 he attempted suicide by slitting his wrists, taking pills and turning on the gas. Thomas Mann wrote to a friend: "My two sisters committed suicide, and Klaus has much of the elder sister in him. The impulse is present in him, and all the circumstances favour it – the one exception being that he has a parental home on which he can always rely."

At the beginning of January 1949, Klaus Mann wrote in his diary: "I do not wish to survive this year." In April, in Cannes, he received a letter from a West German publisher to say that his novel, Mephisto, could not be published in the country because of the objections of Gustaf Gründgens (the book is a thinly-disguised portrait of Gründgens, who abandoned his conscience to ingratiate himself with the Nazi Party).

Klaus wrote to Erika about his problems with his publisher and his financial difficulties. "I have been luck with my family. One cannot be entirely lonely if one belongs to something and is part of it." Klaus Mann died in of an overdose of sleeping pills on 21st May 1949.

Erika and Thomas Mann were in Stockholm when they heard the news. Thomas wrote: "My inward sympathy with the mother’s heart and with Erika. He should not have done this to them... The hurtful, ugly, cruel inconsideration and irresponsibility." Thomas wrote to Hermann Hesse: "This interrupted life lies heavily on my mind and grieves me. My relationship to him was difficult and not free of guilt. My life put his in a shadow right from the beginning."

Thomas Mann decided not to attend his son’s funeral or interrupt his lecture tour. Later, Elisabeth Mann would say of Erika: "When Klaus died, she was totally, totally heartbroken - I mean that was unbearable for her, that loss. That hit her harder than anything else in her life."

Erika Mann, Thomas Mann and his brother Heinrich Mann, continued to be active in left-wing politics. Heinrich, who was planning to move to East Germany, died on 14th March, 1950. Erika and Thomas were both supporters of the American Peace Crusade. Established by Paul Robeson, William Du Bois and Linus Pauling, it called for a cease-fire in Korea, negotiations with the Soviet Union, and the admission of China to the United Nations. Thomas and Erika were attacked in the press and the New York Times stated that they should avoid anything "which involves... the name of Paul Robeson as you would the Bubonic Plague."

The newspaper refused to publish Mann's letter of complaint. Mann told Alfred A. Knopf that Agnes Meyer had been responsible for stopping its publication: "She (Agnes Meyer) threatened me with the loss of my citizenship; accused me of being a traitor to my country; predicted that I would plunge both myself and all those near me into disaster and perdition; and wound up by offering to save my soul."

By 1950, there was a move to deport Erika Mann because they suspected she was a secret member of the Communist Party of the United States. On hearing the news the whole family decided to move to Kilchberg, Switzerland. Thomas Mann died three years later at the age of 80.

Erika Mann spent the next few years editing a three-volume edition of her father’s letters, fighting the case for Klaus Mann’s book, Mephisto, in the West German courts, and battling with her first husband after all these years. When two German newspapers insinuated that she had had an incestuous relationship with Klaus, she sued and won.

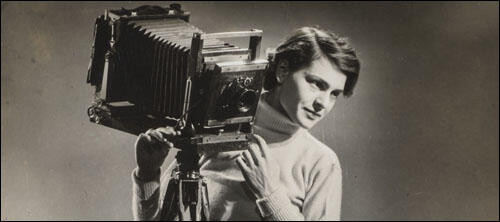

On this day in 1971 photographer Margaret Bourke-White died at Darien, Connecticut.

Margaret Bourke-White was born in New York City on 14th June, 1904. She became interested in photography while studying at Cornell University. After studying photography under Clarence White at Columbia University she opened a studio in Cleveland where she specialized in architectural photography.

In 1929 Bourke-White was recruited by Henry Luce as staff photographer for Fortune Magazine. She made several trips to the Soviet Union and in 1931 published Eyes on Russia. Deeply influence by the impact of the Depression, she became increasingly interested in politics. In 1936 Bourke-White joined Life Magazine and her photograph of the Fort Peck Dam appeared on its first front-cover.

In 1937 Bourke-White worked with the best-selling novelist, Erskine Caldwell, on the book You Have Seen Their Faces (1937). The book was later criticised for its left-wing bias and upset whites in the Deep South with its passionate attack on racism. Carl Mydans of Life Magazine later said that: "Margaret Bourke-White's social awareness was clear and obvious. All the editors at the magazine were aware of her commitment to social causes."

With other left-wing artists such as Stuart Davis, Rockwell Kent, and William Gropper, Bourke-White was a member of the American Artists' Congress. The group supported state-funding of the arts, fought discrimination against African American artists, and supported artists fighting against fascism in Europe. Bourke-White also subscribed to the Daily Worker and was a member of several Communist Party front organizations such as the American League for Peace and Democracy and the American Youth Congress

Bourke-White married Erskine Caldwell in 1939 and the couple were the only foreign journalists in the Soviet Union when the German Army invaded in 1941. Bourke-White and Caldwell returned to the United States where they produced another attack on social inequality, Say Is This the USA? (1942).

During the Second World War Bourke-White served as a war correspondent, working for both Life Magazine and the U.S. Air Force. Bourke-White, who survived a torpedo attack while on a ship to North Africa, was with United States troops when they reached the Buchenwald Concentration Camp.

After the war Bourke-White continued her interest in racial inequality by documenting Gandhi's non-violent campaign in India and apartheid in South Africa.

The FBI had been collecting information on Bourke-White's political activities since the 1930s and in the 1950s became a target for Joe McCarthy and the House of Un-American Activities Committee. However, a statement reaffirming her belief in democracy and her opposition to dictatorship of the left or of the right, enabled her to avoid being cross-examined by the committee.

Bourke-White also covered the Korean War where she took what she considered was her best ever photograph. This was of a meeting between a returning soldier and his mother, who thought he had been killed several months earlier.

In 1952 Margaret Bourke-White was discovered to be suffering from Parkinson's Disease. Unable to take photographs, she spent eight years writing her autobiography, Portrait of Myself (1963).