Boy Soldiers

The British Army only had 750,000 men in August 1914. The war minister, Field-Marshall Lord Kitchener, decided Britain would need another 500,000 men to help defeat Germany. A combination of well-designed posters and passionate recruitment speeches encouraged thousands of men men to join the armed forces.

By the end of August over 300,000 men had answered the call at army recruitment centres. Many of those who had signed up were younger than the official minimum age of nineteen. The recruitment campaign was meant to encourage adults to sign up for the armed forces. Unfortunately, some younger citizens saw the posters and thought that it would be fun to be in the army. Others saw the army as an opportunity to travel or to get away from strict parents.

George Coppard has admitted: "Although I seldom saw a newspaper, I knew about the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand at Sarajevo. News placards screamed out at every street corner, and military bands blared out their martial music in the main streets of Croydon. This was too much for me to resist, and as if drawn by a magnate, I knew I had to enlist straight away."

James Lovegrove was only sixteen but he came under pressure from members of the Order of the White Feather to join the armed forces: "On my way to work one morning a group of women surrounded me. They started shouting and yelling at me, calling me all sorts of names for not being a soldier! Do you know what they did? They struck a white feather in my coat, meaning I was a coward. Oh, I did feel dreadful, so ashamed." Although he was under-age he decided to join the British Army.

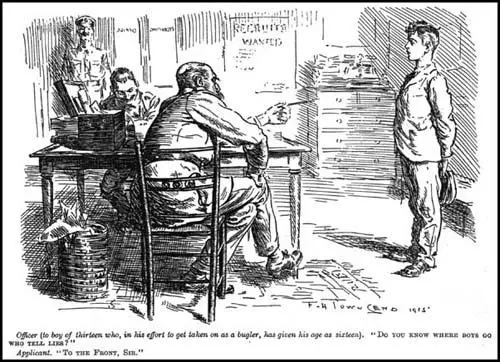

Hundreds of boys falsified birth dates to meet the minimum age requirements. Desperate for soldiers, recruiting officers did not always check the boy's details very carefully. A sixteen year-old later told of how he was able to join the army: "The recruiting sergeant asked me my age and when I told him he said, 'You had better go out, come in again, and tell me different.' I came back, told him I was nineteen and I was in." Private E. Lugg was able to join the 13th Royal Sussex Regiment at the age of thirteen. 1915."

However, he was not the youngest soldier in the British Army, Private Lewis served at the Somme when he was only twelve. George Maher, who was only 13 at the time, claims that Lewis was too short to see over the edge of the trench."The youngest was 12 years old. A little nuggety bloke he was, too. We joked that the other soldiers would have had to have lifted him up to see over the trenches." Maher was eventually arrested: "I was locked up on a train under guard, one of five under-age boys caught serving on the front being sent back to England."

John Cornwell was only sixteen when he won the Victoria Cross for bravery. Cornwall was on board the Chesterwhen it was attacked by four German light cruisers. Within a few minutes the Chester received seventeen hits. Thirty of her crew were killed in the bombardment and another forty-six were seriously wounded. Cornwall remained at his post on one of the ship's guns until the attack was over, but later died of his wounds.

It is claimed that the youngest boy to be killed during the First World War is John Condon of Waterford, who was a member of the Royal Irish Regiment when he was killed aged 14 on the Western Front. Some sources claim that Condon was actually aged 18. However, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, after seeing the relevant documents, still believe that he was 14. In fact, the Waterford News & Star has argued that he was only 13: "The youngest casualty of the First World War had not yet reached his 14th birthday when he was killed on the fields of Flanders in Southern Belgium... John Condon's family only discovered he was in Belgium when they were contacted by the British Army after he went missing in action on the 24th of May 1915."

boys go who tell lies?" Applicant: "To the Front, Sir."

F. H. Townsend, Punch Magazine (11th August, 1916)

Victor Silvester, a fourteen year old schoolboy, ran away from Ardingly College in 1914 to join the army. The recruiting officer accepted Victor's claim that he was nineteen and soon after his fifteenth birthday he was fighting on the Western Front. Victor's parents suspected he had joined the army and informed the authorities but it was not until he was wounded in 1917 that he was discovered and brought home.

On the battlefield, however, young soldiers were finding out that it was not as enjoyable as they had thought it would be. Silvester was ordered to be a member of a firing squad that executed five British soldiers for desertion. People who were late in signing up for the army began to hear about the horrors of trench war. Consequently the number of boy soldiers declined and so it was left to adults to face the terror of the battlefield.

Primary Sources

(1) Victor Silvester wrote about his experiences in the First World War in his autobiography Dancing Is My Life.

The mood of the country was one of almost hysterical patriotism, and no excuses were accepted for any man of military age who was not in uniform. Rude remarks were made about them in the streets. Sometimes they were given white feathers.

I was fourteen and nine months on the morning I played truant, and went up to the headquarters of the London Scottish at Buckingham Palace Gate. A sergeant in the recruiting office asked me what I wanted, and when I told him I had come to join the regiment he questioned me about my Scottish ancestry.

"My mother's father was a Scot," I said.

That seemed adequate, so he asked me my age.

"Eighteen and nine months."

"All right," the sergeant said. "Fill in this form and wait in the next room for the medical officer to look at you."

(2) Victor Silvester soon discovered that the war was very different to what he expected.

We went up into the front-line near Arras, through sodden and devastated countryside. As we were moving up to the our sector along the communication trenches, a shell burst ahead of me and one of my platoon dropped. He was the first man I ever saw killed. Both his legs were blown off and the whole of his face and body was peppered with shrapnel. The sight turned my stomach. I was sick and terrified, but even more frightened of showing it.

That night I had been asleep in a dugout about three hours when I woke up feeling something biting my hip. I put my hand down and my fingers closed on a big rat. It had nibbled through my haversack, my tunic and pleated kilt to get at my flesh. With a cry of horror I threw it from me.

(3) George Coppard was sixteen when he joined the Royal West Surrey Regiment on 27th August, 1914.

Although I seldom saw a newspaper, I knew about the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand at Sarajevo. News placards screamed out at every street corner, and military bands blared out their martial music in the main streets of Croydon. This was too much for me to resist, and as if drawn by a magnate, I knew I had to enlist straight away.

I presented myself to the recruiting sergeant at Mitcham Road Barracks, Croydon. There was a steady stream of men, mostly working types, queuing to enlist. The sergeant asked me my age, and when told, replied, "Clear off son. Come back tomorrow and see if you're nineteen, eh?" So I turned up again the next day and gave my age as nineteen. I attested in a batch of a dozen others and, holding up my right hand, swore to fight for King and Country. The sergeant winked as he gave me the King's shilling, plus one shilling and ninepence ration money for that day.

(4) After the war, Lieutenant Cloete wrote about one of the boy soldiers in his battalion.

I spent most of the day in the trenches, checking snipers' reports, sniping myself and watching the German line from behind a heavy iron loophole with a high-powered telescope. My best sniper turned out, when his parents at last traced him, to be only fourteen years old. He was big for his age and had lied about it when he enlisted under a false name, and then had sufficient restraint to write to no one. I noticed that he received no mail and wrote no letters but had never spoken to him about it. He was discharged as under age. He was the finest shot and the best little soldier I had. A very nice boy, always happy. I got him a military medal and when he went back to England and, I suppose to school, he had a credit of six Germans hit.

(5) ln his autobiography, A Subaltern's War, Charles Edmonds wrote about a boy soldier who only revealed his age when he was about to take part in his first attack on German trenches.

An N.C.O. came up and said that Private Eliot wished to speak to me. I found him crouched against a chalk-heap almost in tears. He looked younger than ever.

"I don't want to go over" he flung at me in the shamelessness of terror, "I'm only seventeen, I want to go home."

The other men standing round avoided my eye and looked rather sympathetic than disgusted.

"Can't help that now, my lad," said I, "you should have thought of that when you enlisted. Didn't you give your age as nineteen then?"

"Yes, sir. But I'm not, I'm only - well, I'm not quite seventeen really, sir."

"Well, it's too late now," I said, "you'll have to see it through and I'll do what I can for you when we come out." I slapped him on the shoulder. You go with the others. You'll be all right when you get started. This is the worse part of it - the waiting, and we're none of us enjoying it."

(6) At the age of fourteen, Victor Silvester ran away from Ardingly College and joined the army. In an interview he gave just before his death in 1978, he described how he was ordered to execute a man for desertion.

We marched to the quarry outside Staples at dawn. The victim was brought out from a shed and led struggling to a chair to which he was then bound and a white handkerchief placed over his heart as our target area. He was said to have fled in the face of the enemy.

Mortified by the sight of the poor wretch tugging at his bonds, twelve of us, on the order raised our rifles unsteadily. Some of the men, unable to face the ordeal, had got themselves drunk overnight. They could not have aimed straight if they tried, and, contrary to popular belief, all twelve rifles were loaded. The condemned man had also been plied with whisky during the night, but I remained sober through fear.

The tears were rolling down my cheeks as he went on attempting to free himself from the ropes attaching him to the chair. I aimed blindly and when the gunsmoke had cleared away we were further horrified to see that, although wounded, the intended victim was still alive. Still blindfolded, he was attempting to make a run for it still strapped to the chair. The blood was running freely from a chest wound. An officer in charge stepped forward to put the finishing touch with a revolver held to the poor man's temple. He had only once cried out and that was when he shouted the one word 'mother'. He could not have been much older than me. We were told later that he had in fact been suffering from shell-shock, a condition not recognised by the army at the time. Later I took part in four more such executions.

(7) James Lovegrove was only sixteen when he joined the army on the outbreak of the First World War.

On my way to work one morning a group of women surrounded me. They started shouting and yelling at me, calling me all sorts of names for not being a soldier! Do you know what they did? They struck a white feather in my coat, meaning I was a coward. Oh, I did feel dreadful, so ashamed.

I went to the recruiting office. The sergeant there couldn't stop laughing at me, saying things like "Looking for your father, sonny?", and "Come back next year when the war's over!" Well, I must have looked so crestfallen that he said "Let's check your measurements again". You see, I was five foot six inches and only about eight and a half stone. This time he made me out to be about six feet tall and twelve stone, at least, that is what he wrote down. All lies of course - but I was in!"

(8) Waterford News & Star (7th November, 2003)

The youngest casualty of the First World War had not yet reached his 14th birthday when he was killed on the fields of Flanders in Southern Belgium.

The story of John Condon, the boy soldier from Waterford City, is the subject of a Nationwide WW1 special on the Eve of Armistice Day, Monday next, Nov. 10th, at 7pm on RTE 1 television. The programme tells the story of how this young Waterford lad trained for military service in the army barracks in Clonmel, after he fooled a British Army recruiting officer into believing he was 18 years of age. John Condon's family only discovered he was in Belgium when they were contacted by the British Army after he went missing in action on the 24th of May 1915.

Condon's father informed the military authorities of his son's real age and the British Military records were amended.

The record of the youngest soldier to die in World War One is now in the record books in London. Ten years would pass before John Condon's body would be discovered by a farmer and his remains finally laid to rest in Poelcapple cemetery near Ypres.

In February of this year - eighty years after John Condon was buried - the nephew and a cousin of the boy soldier became the first blood relatives to come and pay their respects at his graveside. What the family discovered is that the grave of their uncle is the most visited of all the war graves in that country and that their uncle John is hero to the Belgians.

The NATIONWIDE team accompanied John and Sonny Condon on their journey of discovery into a past that they and the Irish people had largely buried, along with the 35,000 other Irishmen who gave up their lives in the war they said would end all wars.

Even today, in Waterford City, John Condon's memory is largely forgotten and recent attempts to erect a monument to his memory were met with opposition from some who still cannot see fit to remember those Irishmen who died wearing a British uniform.

(9) Julie Henry, The Daily Telegraph (31st October, 2009)

The child, said to be too short to see over the edge of a trench, was recalled by another under-age soldier, George Maher, who was only 13 when he was sent to the Somme during the First Wold War.

Mr Maher had told a recruiting officer that he was 18 to enable him to join the 2nd King's Own Royal Lancaster Regiment in 1917. But his true age was revealed when he broke down in tears under shellfire and was hauled before an unsympathetic officer.

Mr Maher, who died aged 96 in 1999, remembered: "I was locked up on a train under guard, one of five under-age boys caught serving on the front being sent back to England.

"The youngest was 12 years old. A little nuggety bloke he was, too. We joked that the other soldiers would have had to have lifted him up to see over the trenches."

Mr Maher's story, reported in The Sun, has been collected by historian Richard Van Emden for his book: Veterans: The Last Survivors Of The Great War.