On this day on 23rd December

On this day in 1732 Richard Arkwright, the sixth of the seven children of Thomas Arkwright (1691–1753), a tailor, and his wife, Ellen Hodgkinson (1693–1778), was born in Preston. Richard's parents were very poor and could not afford to send him to school and instead arranged for him to be taught to read and write by his cousin Ellen.

Richard became a barber's apprentice at Kirkham before moving to Bolton. He worked for Edward Pollit and in 1754 he started his own business as a wig-maker. The following year he married Patience Holt, the daughter of a schoolmaster. Their only child, Richard Arkwright, was born on 19th December 1755. After the death of his first wife he married Margaret Biggins (1723–1811) on 24th March 1761.

Arkwright's work involved him travelling the country collecting people's discarded hair. In September 1767 Arkwright met John Kay, a clockmaker, from Warrington, who had been busy for some time trying to produce a new spinning-machine with another man, Thomas Highs of Leigh. Kay and Highs had run out of money and had been forced to abandon the project. Arkwright was impressed by Kay and offered to employ him to make this new machine.

Arkwright also recruited other local craftsman, including Peter Atherton, to help Kay in his experiments. According to one source: "They rented a room in a secluded teacher's house behind some gooseberry bushes, but they were so secretive that the neighbours were suspicious and accused them of sorcery, and two old women complained that the humming noises they heard at night must be the devil tuning his bagpipes."

As the economic historian, Thomas Southcliffe Ashton, has pointed out, Arkwright did not have any great inventive ability, but "had the force of character and robust sense that are traditionally associated with his native county - with little, it may be added, of the kindliness and humour that are, in fact, the dominant traits of Lancashire people."

In 1768 the team produced the Spinning-Frame and a patent for the new machine was granted in 1769. The machine involved three sets of paired rollers that turned at different speeds. While these rollers produced yarn of the correct thickness, a set of spindles twisted the fibres firmly together. The machine was able to produce a thread that was far stronger than that made by the Spinning-Jenny produced by James Hargreaves.

Adam Hart-Davis has explained the way the new machine worked: "Several spinning machines were designed at about this time, but most of them tried to do the stretching and the spinning together. The problem is that the moment you start twisting the roving you lock the fibres together. Arkwright's idea was to stretch first and then twist. The roving passed from a bobbin between a pair of rollers, and then a couple of inches later between another pair that were rotating at twice the speed. The result was to stretch the roving to twice its original length. A third pair of rollers repeated the process... Two things are obvious the moment you see the wonderful beast in action. First, there are 32 bobbins along each side of each end of the water frame - 128 on the whole machine. Second, it is so automatic that even I could operate it."

On 29th September 1769 Richard Arkwright rented premises in Nottingham. However, he had difficulty finding investors in his new company. David Thornley, a merchant, of Liverpool, and John Smalley, a publican from Preston, did provide some money but he still needed more to start production. Arkwright approached a banker Ichabod Wright but he rejected the proposal because he judged that there was "little prospect of the discovery being brought into a practical state".

Wright introduced Arkwright to Jedediah Strutt and Samuel Need. Strutt was a manufacturer of stockings and the inventor of a machine for the machine-knitting of ribbed stockings. Strutt and Need were impressed with Arkwright's new machine and agreed to form a partnership. On 19th January 1770, for £500, Need and Strutt joined the partners; Arkwright, Thornley and Smalley, were to manage the works, each having £25 a year. Financially secure, the partners commissioned Samuel Stretton to convert the premises into a horse-powered mill.

Arkwright's machine was too large to be operated by hand and so the men had to find another method of working the machine. After experimenting with horses, it was decided to employ the power of the water-wheel. In 1771 the three men set up a large factory next to the River Derwent in Cromford, Derbyshire. Arkwright later that his lawyer that Cromford had been chosen because it offered "a remarkable fine stream of water… in an area very full of inhabitants". Arkwright's machine now became known as the Water-Frame. It not only "spun cotton more rapidly but produced a yarn of finer quality".

Arkwright did not build the first factory in Britain. It is believed that he borrowed the idea from Matthew Boulton, who financed the Soho Manufactory in Birmingham in 1762. However, Arkwright's factory was much larger and was to inspire a generation of capitalist entrepreneurs. According to Adam Hart-Davis: "Arkwright's mill was essentially the first factory of this kind in the world. Never before had people been put to work in such a well-organized way. Never had people been told to come in at a fixed time in the morning, and work all day at a prescribed task. His factories became the model for factories all over the country and all over the world. This was the way to build a factory. And he himself usually followed the same pattern - stone buildings 30 feet wide, 100 feet long, or longer if there was room, and five, six, or seven floors high."

In Cromford there were not enough local people to supply Arkwright with the workers he needed. After building a large number of cottages close to the factory, he imported workers from all over Derbyshire. Within a few months he was employing 600 workers. Arkwright preferred weavers with large families. While the women and children worked in his spinning-factory, the weavers worked at home turning the yarn into cloth.

A local journalist wrote: "Arkwright's machines require so few hands, and those only children, with the assistance of an overlooker. A child can produce as much as would, and did upon an average, employ ten grown up persons. Jennies for spinning with one hundred or two hundred spindles, or more, going all at once, and requiring but one person to manage them. Within the space of ten years, from being a poor man worth £5, Richard Arkwright has purchased an estate of £20,000; while thousands of women, when they can get work, must make a long day to card, spin, and reel 5040 yards of cotton, and for this they have four-pence or five-pence and no more."

Peter Kirby, the author of Child Labour in Britain, 1750-1870 (2003) has argued that it was poverty that forced children into factories: "Poor families living close to a subsistence wage were often forced to draw on more diverse sources of income and had little choice over whether their chidren worked." Michael Anderson has pointed out, that parents "who otherwise showed considerable affection for their children... were yet forced by large families and low wages to send their children to work as soon as possible."

The youngest children in the textile factories were usually employed as scavengers and piecers. Piecers had to lean over the spinning-machine to repair the broken threads. One observer wrote: "The work of the children, in many instances, is reaching over to piece the threads that break; they have so many that they have to mind and they have only so much time to piece these threads because they have to reach while the wheel is coming out."

Scavengers had to pick up the loose cotton from under the machinery. This was extremely dangerous as the children were expected to carry out the task while the machine was still working. David Rowland, worked as a scavenger in Manchester: "The scavenger has to take the brush and sweep under the wheels, and to be under the direction of the spinners and the piecers generally. I frequently had to be under the wheels, and in consequence of the perpetual motion of the machinery, I was liable to accidents constantly. I was very frequently obliged to lie flat, to avoid being run over or caught."

John Fielden, a factory owner, admitted that a great deal of harm was caused by the children spending the whole day on their feet: " At a meeting in Manchester a man claimed that a child in one mill walked twenty-four miles a day. I was surprised by this statement, therefore, when I went home, I went into my own factory, and with a clock before me, I watched a child at work, and having watched her for some time, I then calculated the distance she had to go in a day, and to my surprise, I found it nothing short of twenty miles."

Unguarded machinery was a major problem for children working in factories. One hospital reported that every year it treated nearly a thousand people for wounds and mutilations caused by machines in factories. Michael Ward, a doctor working in Manchester told a parliamentary committee: "When I was a surgeon in the infirmary, accidents were very often admitted to the infirmary, through the children's hands and arms having being caught in the machinery; in many instances the muscles, and the skin is stripped down to the bone, and in some instances a finger or two might be lost. Last summer I visited Lever Street School. The number of children at that time in the school, who were employed in factories, was 106. The number of children who had received injuries from the machinery amounted to very nearly one half. There were forty-seven injured in this way."

William Blizard lectured on surgery and anatomy at the Royal College of Surgeons. He was especially concerned about the impact of this work on young females: "At an early period the bones are not permanently formed, and cannot resist pressure to the same degree as at a mature age, and that is the state of young females; they are liable, particularly from the pressure of the thigh bones upon the lateral parts, to have the pelvis pressed inwards, which creates what is called distortion; and although distortion does not prevent procreation, yet it most likely will produce deadly consequences, either to the mother or the child, when the period."

Elizabeth Bentley, who came from Leeds, was another witness that appeared before the committee. She told of how working in the card-room had seriously damaged her health: "It was so dusty, the dust got up my lungs, and the work was so hard. I got so bad in health, that when I pulled the baskets down, I pulled my bones out of their places." Bentley explained that she was now "considerably deformed". She went on to say: "I was about thirteen years old when it began coming, and it has got worse since."

Samuel Smith, a doctor based in Leeds explained why working in the textile factories was bad for children's health: "Up to twelve or thirteen years of age, the bones are so soft that they will bend in any direction. The foot is formed of an arch of bones of a wedge-like shape. These arches have to sustain the whole weight of the body. I am now frequently in the habit of seeing cases in which this arch has given way. Long continued standing has also a very injurious effect upon the ankles. But the principle effects which I have seen produced in this way have been upon the knees. By long continued standing the knees become so weak that they turn inwards, producing that deformity which is called 'knock-knees' and I have sometimes seen it so striking, that the individual has actually lost twelve inches of his height by it."

John Reed later recalled his life aa a child worker at Cromford Mill: "I continued to work in this factory for ten years, getting gradually advanced in wages, till I had 6s. 3d. per week; which is the highest wages I ever had. I gradually became a cripple, till at the age of nineteen I was unable to stand at the machine, and I was obliged to give it up. The total amount of my earnings was about 130 shillings, and for this sum I have been made a miserable cripple, as you see, and cast off by those who reaped the benefit of my labour, without a single penny."

Richard Arkwright originally produced cotton yarn for stockings, but its possibilities as warp for the loom led, in 1773, to the manufacture of calicos. Jedediah Strutt took responsibility for lobbying Parliament and eventually persuaded its members to reduce excise duties on British-made cotton goods. By February 1774 the partners could, according to Elizabeth Strutt, "sell them … as fast as we could make them."

As J. J. Mason has pointed out: "From the mid-1770s he sought to dominate the trade. In 1775 he successfully applied for a patent for certain instruments and machines for preparing silk, cotton, flax, and wool, for spinning. Covering a range of preparatory and spinning machines, it was an attempt to extend the length and terms of his monopoly to the whole cotton industry".

When businessmen heard about Arkwright's success, they sent spies to find out what was going on in his factories. In exchange for money, some of Arkwright's employees were willing to explain how the factory was organised. Businessmen then used this information to build their own water-powered textile factories. This included spies sent from "many different countries, from Russia, Denmark, Sweden and Prussia, but the most eager of the spies were from Britain's greatest rival, France."

Ralph Mather reported that Arkwright feared that Luddites would destroy his factory: "There is some fear of the mob coming to destroy the works at Cromford, but they are well prepared to receive them should they come here. All the gentlemen in this neighbourhood being determined to defend the works, which have been of such utility to this country. 5,000 or 6,000 men can be at any time assembled in less than an hour by signals agreed upon, who are determined to defend to the very last extremity, the works, by which many hundreds of their wives and children get a decent and comfortable livelihood."

Eric Hobsbawm has argued that in his dealings with his partners he was an "unscrupulous operator". (30) Matthew Boulton described him as a "tyrant". John Smalley suggested to Jedediah Strutt that they should force Arkwright out of the company. Strutt replied. "We cannot stop his mouth or prevent his doing wrong.... but it is not in our power to remove him… for he is in possession and as much right there as we."

Arkwright made further money by selling the rights to use his machines. With the 1769 patent due to expire in the summer of 1783, Arkwright faced losing his controlling hold on the cotton industry. He petitioned parliament that his patents be consolidated and the 1769 patent extended to 1789. However, as Jenny Uglow points out: "Since 1781 Lancashire cotton-spinners had spent a fortune on buildings and machines, employing around thirty thousand people - men, women, and children. They could not afford to become his licensees at prohibitive rates."

In April, 1781, his competitors applied to have the decision annulled. The trial took place in June. Arkwright employed the finest lawyers and an array of witnesses. John Kay and Thomas Highs both gave evidence against Arkwright. He lost the case and a broadsheet in Manchester crowed that "the old Fox is at last caught by his over-grown beard in his own trap".

Arkwright was furious with this decision and he argued that the court's decision would halt the work of other inventors. James Watt, was one of those who gave his support to Arkwright's campaign to extend his patents. Rumours circulated that he was trying to buy up the world's cotton crop. This did not happen but he did set up a company to establish cotton plantations in Africa.

Despite this set-back Arkwright he remained the country's largest cotton spinner; he made huge gains in the 1770s, and even in the early 1780s his profits from the industry seem to have been at 100 per cent per annum. Thomas Carlyle described Arkwright as "a plain, almost gross, bag-cheeked, pot-bellied man, with an air of painful reflection, yet almost copious free digestion".

When Samuel Need died on 14th April, 1781. Arkwright and Jedediah Strutt decided to dissolve their partnership. Strutt was disturbed by Arkwright's plans to build mills in Manchester, Winkworth, Matlock Bath and Bakewell. Strutt believed that Arkwright was expanding too fast and without the support of Need, his long-time partner, he was unwilling to take the risk of further investments. Arkwright's textile factories were very profitable. He now built factories in Lancashire, Staffordshire and Scotland. In these factories he used the new steam-engine that had recently been developed by James Watt and Matthew Boulton.

Arkwright's biographer, J. J. Mason, claimed that: "In 1782 he bought Willersley manor and in 1789 the manor of Cromford. These acquisitions established him more firmly with the local gentry, including the Gells and Nightingales, with whom he was already connected through business.... Society sneered at his extravagance and ridiculed his gauche behaviour... but enjoyed his lavish entertainments in... Rock House, perched high and overlooking the mills and his more stately home, Willersley Castle."

Richard Arkwright was made Sheriff of Derbyshire and was knighted in 1787. King George III told Wilhelmina Murray, that he did not deal very well with the ceremony. "Tthe little great man had no idea of kneeling but crimpt himself up in a very odd posture which I suppose His Majesty took for an easy one so never took the trouble to bid him rise."

Richard Arkwright's employees worked from six in the morning to seven at night. Although some of the factory owners employed children as young as five, Arkwright's policy was to wait until they reached the age of six. Two-thirds of Arkwright's 1,900 workers were children. Like most factory owners, Arkwright was unwilling to employ people over the age of forty.

William Dodd carried out a study into the long-term impact on the physical health of these child workers. This included an interview with John Reed: "Here is a young man, who was evidently intended by nature for a stout-made man, crippled in the prime of life, and all his earthly prospects blasted for ever! Such a cripple I have seldom met with. He cannot stand without a stick in one hand, and leaning on a chair with the other; his legs are twisted in all manner of forms. His body, from the forehead to the knees, forms a curve, similar to the letter C. He dares not go from home, if he could; people stare at him so."

Dodd compared the life of John Reed with that of Richard Arkwright: "I have taken several walks in the neighbourhood of this beautiful and romantic place, and seen the splendid castle, and other buildings belonging to the Arkwrights, and could not avoid contrasting in my mind the present condition of this wealthy family, with the humble condition of its founder in 1768. One might expect that those who have thus risen to such wealth and eminence, would have some compassion upon their poor cripples. If it is only that they need to have them pointed out, and that their attention has hitherto not been drawn to them, I would hope and trust this case of John Reed will yet come under their notice."

Arkwright had difficulty making friends and Josiah Wedgwood claimed that "he shuns all company as much as possible". Archibald Buchanan, who lived with him and found him "so intent on his schemes" they "often sat for weeks together, on opposite sides of the fire without exchanging a syllable".

Richard Arkwright died aged 59 on 3rd August 1792 at his home in Cromford, after a month's illness. On 10th August, over 2,000 by two people attended his funeral. The Gentleman's Magazine claimed that on his death, Arkwright was worth over £500,000 (over £200 million in today's money).

On this day in 1812 Samuel Smiles, the eldest of eleven children, was born. Samuel's parents ran a small general store in Haddington in Scotland. After attending the local school he left at fourteen and joined Dr. Robert Lewins as an apprentice.

After making good progress with Dr. Lewins, Smiles went to Edinburgh University in 1829 to study medicine. While in Edinburgh, Smiles became involved in the campaign for parliamentary reform. During this period he had several articles on the subject published by the progressive Edinburgh Weekly Chronicle.

Smiles graduated in 1832 and found work as a doctor in Haddington. Smiles continued to take a close interest in politics and became a strong supporter of Joseph Hume, the Scottish radical politician from Montrose. Hume, like Smiles, had trained as a doctor at Edinburgh University.

In 1837 Samuel Smiles began contributing articles on parliamentary reform for the Leeds Times. The following year he was invited to become the newspaper's editor. Smiles decided to abandon his career as a doctor and to become a full-time worker for the cause of political change. In the newspaper Smiles expressed his powerful dislike of the aristocracy and made attempts to unite working and middle class reformers. Smiles also employed his newspaper in the campaign in favour of factory legislation.

In May 1840 Smiles became Secretary to the Leeds Parliamentary Reform Association, an organisation that believed in household suffrage, the secret ballot, equal representation, short parliaments and the abolition of the property qualification for parliamentary candidates.

In the 1840s Smiles became disillusioned with Chartism. Although Smiles still supported the six points of the Charter, he was worried by the growing influence of Feargus O'Connor, George Julian Harney and the other advocates of Physical Force. Smiles now argued that "mere political reform will not cure the manifold evils which now afflict society." Smiles stressed the importance of "individual reform" and promoted the idea of "self-help".

Samuel Smiles began to take a close interest in the ideas of Robert Owen. He contributed articles to Owen's journal, The Union. Smiles also helped the co-operative movement in Leeds. This included the Leeds Mutual Society and the Leeds Redemption Society.

In 1845 Samuel Smiles left the Leeds Times and became secretary to the Leeds and Thirsk Railway. After nine years with the Leeds and Thirsk Railway he took up a similar post with the South-Eastern Railway.

In the 1850s Samuel Smiles completely abandoned his interest in parliamentary reform. Smiles now argued that self-help provided the best route to success. His book Self-Help, which preached industry, thrift and self-improvement was published in 1859. Smiles also wrote a series of biographies of men who had achieved success through hard-work. This included George Stephenson (1875), Lives of the Engineers (1861) and Josiah Wedgwood (1894). Samuel Smiles died on 16th April, 1904.

On this day in 1852 socialist orator Fanny Wright died. As requested, her tombstone in Cincinnati was inscribed with the words: "I have wedded the cause of human improvement, staked on it my fortune, my reputation and my life."

Fanny Wright was born in Dundee on 6th September, 1795. Both her father, a wealthy Scottish linin manufacturer, and her mother died by the time she was three years old. Wright was brought up in the homes of relatives, including James Milne, a member of Scottish school of progressive philosophers. Milne, who encouraged Fanny to question conventional ideas, was to have a lasting influence on her political development.

Wright visited the USA in 1818 and after returning to England published her observations of the country in her book, Views of Society and Manners in America (1821). The book praised America's experiments in democracy and provided information for those radicals in Britain involved in the struggle for parliamentary reform.

In England she became friendly with the Marquis de Lafayette and together they returned to the United States in 1824. Later that year Wright visited New Harmony in Indiana, the socialist community established by Robert Owen and his son Robert Dale Owen. She was immediately converted to Owenism and decided to form her own co-operative community.

In 1825 Wright purchased 2,000 acres of woodland thirteen miles from Memphis in Tennessee and formed a community called Nashoba. Wright then bought slaves from neighbouring farmers, freed them, and gave them land on her settlement.

Some aspects of Wright's community were extremely controversial, especially her decision to encourage sexual freedom. She came to believe that miscegenation was the ultimate solution of the racial question. Wright saw marriage as a discriminatory institution and started advocating free love.

Wright also developed her own dress code for women. This included bodices, ankle-length pantaloons and a dress cut to above the knee. This style was later promoted by feminists such as Amelia Bloomer, Susan Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Fanny Wright spent her entire personal fortune on her Nashoba co-operative community. She hoped it would become economically self-sufficient but this did not happen and in 1828 she was forced to abandon her experiment. Wright and Robert Dale Owen arranged for the former slaves to be sent to the black republic of Haiti.

In 1829 Wright settled in New York where she published her book, Course of Popular Lectures. She also combined with Robert Dale Owen to publish the Free Enquirer. In the journal Wright advocated socialism, the abolition of slavery, universal suffrage, free secular education, birth control, changes in the marriage and divorce laws. Wright and Owen also became involved in the radical Workingmen's Party while living in New York.

Fanny Wright married the French doctor, Guillaume P. Darusmont in 1831. The marriage was not a success and ended in divorce. As her husband, Darusmont had managed to gain control over her entire property, including her earnings from lectures and the royalties from her books. Fanny Wright was in the middle of a legal struggle with Darusmont, when she died on 13th December, 1852.

On this day in 1857 Edward Pease, the sixth of fifteen children, was born at Henbury Hill, near Bristol on 23rd December, 1857. Edward was related to Edward Pease the famous railway entrepreneur. His parents, Thomas Pease and Susanna Fry, were both devout Quakers. Edward was educated at home by a private tutor until he reached the age of sixteen.

Pease moved to London in 1874 where he found work as a clerk in his brother-in-law's textile firm. Later he became a partner in a brokerage company. The business was very successful, but Pease, who was gradually developing socialists ideas, became increasingly uncomfortable about his speculative dealings on the Stock Exchange.

In 1881 Pease met Frank Podmore. They discovered a mutual interest in socialism, and joined the Progressive Association, founded in November 1882. They took a keen interest in the utopian philosophy of Thomas Davidson, and with a few others formed a society, the Fellowship of the New Life. Other members included Edward Carpenter, Edith Lees, Edith Nesbit, Isabella Ford, Henry Hyde Champion, Hubert Bland, Edward Pease and Henry Stephens Salt. According to another member, Ramsay MacDonald, the group were influenced by the ideas of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

In October 1883 Edith Nesbit and Hubert Bland decided to form a socialist debating group with Edward Pease. They were also joined by Frank Podmore and Havelock Ellis and in January 1884 they decided to call themselves the Fabian Society. Podmore suggested that the group should be named after the Roman General, Quintus Fabius Maximus, who advocated the weakening the opposition by harassing operations rather than becoming involved in pitched battles. Podmore's home, 14 Dean's Yard, Westminster, became the official headquarters of the organisation.

Hubert Bland chaired the first meeting and was elected treasurer. By March 1884 the group had twenty members. In April 1884 Edith Nesbit wrote to her friend, Ada Breakell: "I should like to try and tell you a little about the Fabian Society - it's aim is to improve the social system - or rather to spread its news as to the possible improvements of the social system. There are about thirty members - some of whom are working men. We meet once a fortnight - and then someone reads a paper and we all talk about it. We are now going to issue a pamphlet. I am on the Pamphlet Committee. Now can you fancy me on a committee? I really surprise myself sometimes."

Over the next couple of years the group increased in size and included socialists such as George Bernard Shaw, Sydney Olivier, William Clarke, Eleanor Marx, Edith Lees, Annie Besant, Graham Wallas, J. A. Hobson, Sidney Webb, Beatrice Webb, Charles Trevelyan, J. R. Clynes, Harry Snell, Clementina Black, Edward Carpenter, Clement Attlee, Ramsay MacDonald, Emmeline Pankhurst,Walter Crane, Arnold Bennett, Sylvester Williams, H. G. Wells, Hugh Dalton, C. E. M. Joad, Rupert Brooke, Clifford Allen and Amber Reeves.

In 1884, Thomas Pease died leaving Edward a legacy of £3,000. This gave Pease the opportunity to give up working on the Stock Exchange and to devote his energies to the socialist cause. Pease also had a desire the become a working man and in 1886 he moved to Newcastle where he found work as a cabinet-maker in a co-operative furniture company. Pease formed a branch of the National Labour Federation and hoped to convert the working class in the area to socialism. However, disillusioned by the workers lack of interest in this new philosophy, Pease returned to London.

Edward Pease travelled to America with Sidney Webb in 1888. Pease considered settling in the country but realising that workers were no more interested in socialism than those at home, returned to England. Soon afterwards he married Marjory Davidson, a young Scottish schoolteacher.

The success of Fabian Essays in Socialism (1889) convinced the Fabian Society that they needed a full-time employee. In 1890 Pease was appointed as Secretary of the Society. His duties included keeping the minutes at meetings, dealing with the correspondence, arranging lecture schedules, managing the Fabian Information Bureau, circulating book-boxes and editing and contributing to the Fabian News. Pease was the author of ten pamphlets published by the Fabian Society. This included The History of the Fabian Society (1916).

In 1894 Henry Hutchinson, a wealthy solicitor from Derby, left the Fabian Society £10,000. Hutchinson left instructions that the money should be used for "propaganda and socialism". Hutchinson selected Pease, Sidney Webb and Beatrice Webb as trustees of the fund, and together they decided the money should be used to develop a new university in London. The London School of Economics (LSE) was founded in 1895. As Sidney Webb pointed out, the intention of the institution was to "teach political economy on more modern and more socialist lines than those on which it had been taught hitherto, and to serve at the same time as a school of higher commercial education".

Edward Pease was also a member of the Independent Labour Party and had close links with people such as Keir Hardie, Robert Smillie, George Bernard Shaw, Tom Mann, George Barnes, John Glasier, H. H. Champion, Ben Tillett, Philip Snowden, Edward Carpenter and Ramsay Macdonald.

On 27th February 1900, Pease represented the Fabian Society at the meeting of socialist and trade union groups at the Memorial Hall in Farringdon Street, London. After a debate the 129 delegates decided to pass Hardie's motion to establish "a distinct Labour group in Parliament, who shall have their own whips, and agree upon their policy, which must embrace a readiness to cooperate with any party which for the time being may be engaged in promoting legislation in the direct interests of labour." To make this possible the Conference established a Labour Representation Committee (LRC). This committee included two members from the Independent Labour Party, two from the Social Democratic Federation, one member of the Fabian Society, and seven trade unionists.

Some members of the Fabian Society had doubts about this and Pease personally paid the affiliation dues. Pease was elected to the executive of the Labour Representation Committee (named the Labour Party after 1906) and held the post for the next fourteen years.

With his wife Marjory, Edward Pease established the East Surrey Labour Party and both of them served on the local council. Their home at Limpsfield became known as Dostoevsky Corner, because he housed so many Russian refugees who had been forced to leave their country because of their socialist beliefs.

Edward Pease was very close to Sidney Webb and fully supported his policy of permeation as opposed to political action. Pease later claimed he allowed Webb to dominate the Fabian Society because he knew "Webb was always right". He also joined forces with Webb to prevent H. G. Wells from changing the Fabian Society into a mass political organisation.

After being left a considerable amount of money by his uncle Joseph Fry in 1913, Pease decided to retire from his duties as Secretary of the Fabian Society. He remained on the executive of the Society until deafness made his participation in discussions impossible. Edward Pease died on 5th January, 1955, at the age of ninety-seven.

On this day in 1873 Sarah Grimke died.

Sarah Grimke, the daughter of slaveholding judge from Charleston, South Carolina, was born on 26th November, 1792. Sarah and her sister, Angelina Grimke, both developed an early dislike of slavery and after moving to Philadelphia in 1819, joined the Society of Friends.

In 1835 Angelina Grimke had a letter against slavery published by William Lloyd Garrison, in his newspaper, The Liberator . She followed this with the pamphlet, An Appeal to the Christian Women of the South. Sarah followed her example by publishing An Epistle to the Clergy of the Southern States. These pamphlets were publicly burned by officials in South Carolina and the sisters were warned that they would be arrested if they ever returned home.

The sisters moved to New York where they became the first women to lecture for the Anti-Slavery Society. This brought attacks from religious leaders who disapproved of women speaking in public. Sarah wrote bitterly that men were attempting to "drive women from almost every sphere of moral action" and called on women "to rise from that degradation and bondage to which the faculties of our minds have been prevented from expanding to their full growth and are sometimes wholly crushed."

Refusing to give up their campaign, the sisters now became pioneers in the struggle forwomen's rights. In her book Letters on the Equality of the Sexes (1838), Grimke linked the rights of slaves to the rights of women. William Lloyd Garrison gave Grimke his support in this but Theodore Weld advised her not to "push your women's rights until human rights have gone ahead."

In 1838 Sara's sister, Angelina Grimke married Theodore Weld. Sarah moved with the couple to Belleville, New Jersey, where they opened their own school. Later they established a progressive school at the Raritan Bay Community in New York.

During the Civil War Sarah wrote and lectured in support of Abraham Lincoln. Sarah Grimke continued to work civil rights and woman's suffrage until her death on 23rd December, 1873.

On this day in 1889 women's suffragist, Victoria Simmons, one of twelve children, was born in Clifton, on 23rd December 1889. Her father was a furniture dealer and held traditional views about the role of women. However, her mother had progressive opinions on politics and religion and as a girl she became a vegetarian. Victoria went to a Dame School and later recalled "spending a great deal of time standing in the corner for asking too many questions". After leaving school at 14 she found work in a photographic studios in Clifton.

In 1907 Victoria and her mother attended a meeting held by Annie Kenney, the recently appointed West of England organiser of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). As a result of hearing Kenney speak, both women joined the WSPU. Over the next couple of years, Victoria made regular speeches in Bristol on women's suffrage. During this period she became friendly with Mary Blathwayt, Mary Allen, Vera Wentworth and Elsie Howey. According to Bella Hoffman: "Most of her suffrage work was done in her home town, Clifton, Bristol. She chalked pavements; sold Votes For Women (and was spat on by a local clergyman for so doing); addressed meetings at Bristol Docks from the back of a lorry; and was told by a docker to get back to the kitchen and the bedroom where she belonged."

During the summer of 1908 the WSPU introduced the tactic of breaking the windows of government buildings. On 30th June suffragettes marched into Downing Street and began throwing small stones through the windows of the Prime Minister's house. As a result of this demonstration, twenty-seven women were arrested and sent to Holloway Prison. During this period Victoria was reluctant to get involved in violent demonstrations.

Emmeline Pankhurst decided that the WSPU needed to intensify its window-breaking campaign. On 1st March, 1912, a group of suffragettes volunteered to take action in the West End of London. The Daily Graphic reported the following day: "The West End of London last night was the scene of an unexampled outrage on the part of militant suffragists.... Bands of women paraded Regent Street, Piccadilly, the Strand, Oxford Street and Bond Street, smashing windows with stones and hammers."

On 4th March, the WSPU organised another window-breaking demonstration. This time the target was government offices in Whitehall. Victoria travelled to London from Bristol to take part in the demonstration. The severely disabled, May Billinghurst, agreed to hide some of the stones underneath the rug covering her knees. According to Votes for Women: "From in front, behind, from every side it came - a hammering, crashing, splintering sound unheard in the annals of shopping... At the windows excited crowds collected, shouting, gesticulating. At the centre of each crowd stood a woman, pale, calm and silent."

Victoria broke a window at the War Office. She later recalled: "He just looked at me. Meantime another policeman rushed up towards me and then an inspector on horseback came. So I was escorted to Bow Street, a policeman each side of me, clutching my arm. and one behind. Well, I had eight stones, but I'd only used one so on the way to the police station I dropped them one by one and to my amazement when I was taken down at Bow Street, this policeman that had followed put the seven stones on the table and said, She dropped these on the way." Victoria was one of 200 suffragettes who was arrested and jailed for taking part in the demonstration.

Victoria got two months. Bella Hoffman has pointed out: "Her memory of Holloway was of one of her own sisters shouting encouraging messages from across the street, standing on a chair in her cell and singing out of the barred window, and the black beetle in her porridge." Under instructions from her mother, Victoria did not go on hunger-strike. As she later pointed out in a BBC interview, although she was willing to go to prison for women's suffrage, she was unable to disobey an order given by her mother.

On 4th August, 1914, England declared war on Germany. The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort.

Emmeline Pankhurst announced that all militants had to "fight for their country as they fought for the vote." Ethel Smyth pointed out in her autobiography, Female Pipings for Eden (1933): "Mrs Pankhurst declared that it was now a question of Votes for Women, but of having any country left to vote in. The Suffrage ship was put out of commission for the duration of the war, and the militants began to tackle the common task."

After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men.

Victoria went along with this policy and during the First World War she and her sister ran a guest-house in Kensington for professional women, and made anti-aircraft shells at Battersea Power Station at the weekends. In 1918 she married Major Alexander Lidiard, of the Fifth Manchester Rifles. They had met while she was selling Votes For Women. He became a supporter of women's suffrage and was an active member of Men's League For Women's Suffrage.

After the war Victoria Lidiard trained as an optician and ran practices with her husband in Maidenhead and High Wycombe. She was a campaigner for animal welfare and a member of the local church council. In 1988 she published Christianity, Faith, Love and Healing. This was followed by Animals and All Churches (1989).

Lidiard was also a supporter of women priests: 'It seems the fight for the ordination of women priests is meeting with the same prejudice as women faced to get the vote. There is no physical, moral, mental, theological or spiritual reason why women should not be ordained... the opposition to the ordination of women is just the same opposition as when we fought for the vote. They could not reason. I don't mind people giving reasons, but not stupid prejudices."

Victoria Lidiard died in Hove, at the age of 102, on 3rd October 1992.

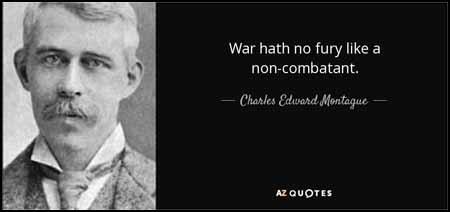

On this day in 1914 Charles Edward Montague joins the British Army. Montague worked for the Manchester Guardian and was C. P. Scott's son-in-law. Montague argued in the summer of 1914 against Britain becoming involved in a war with Germany. However, once war had been declared, Montague believed that it was important to give full support to the British government in its attempts to achieve victory. Montague wrote to Scott: "I have felt for some time, and especially since I have been writing leaders urging people to enlist, a strong wish to do the same myself. I wrote last week to the War Office to ask if there was any chance of getting over the difficulty of my few years over the limit of age, and I was told that although the War Office could not directly break the rule itself, it did not veto exceptions made by those responsible for the raising of new battalions locally."

Although forty-seven with a wife and seven children, Montague volunteered to join the British Army. Grey since his early twenties, Montague died his hair in an attempt to persuade the army to take him. On 23rd December, 1914, the Royal Fusiliers accepted him and he joined the Sportsman's Battalion.

After receiving military training at Climpson Camp in Nottingham, Montague went to France in November, 1915. The following month he wrote to Francis Dodd: "The one thing of which no description given in England any true measure is the universal, ubiquitous muckiness of the whole front. One could hardly have imagined anybody as muddy as everybody is. The rats are pretty well unimaginable too, and, wherever you are, if you have any grub about you that they like, they eat straight through your clothes or haversack to get at it as soon as you are asleep. I had some crumbs of army biscuit in a little calico bag in a greatcoat pocket, and when I awoke they had eaten a big hole through the coat from outside and pulled the bag through it, as if they thought the bag would be useful to carry away the stuff in. But they don't actually try to eat live humans."

When he arrived at the Western Front, his commanding officer questioned the wisdom of having a man in his late forties in the trenches. Montague was sent before the Medical Board and had to wait until the end of January, 1916, before being allowed to return to the trenches. However, three months later, a new ruling banned all men over forty-four from trench work.

The journalist, Philip Gibbs, later recalled: "Prematurely white-haired, he had dyed it when the war began and had enlisted in the ranks. He became a sergeant and then was dragged out of his battalion, made a captain, and appointed as censor to our little group. Extremely courteous, abominably brave - he liked being under shell fire - and a ready smile in his very blue eyes, he seemed unguarded and open. Once he told me that he had declared a kind of moratorium on Christian ethics during the war. It was impossible, he said, to reconcile war with the Christian ideal, but it was necessary to get on with its killing. One could get back to first principles afterwards, and resume one's ideals when the job had been done."

Montague was promoted to the rank of second lieutenant and transferred to Military Intelligence. For the next two years he had the task of writing propaganda for the British Army and censoring articles written by the five authorized English journalists on the Western Front (Perry Robinson, Philip Gibbs, Percival Phillips, Herbert Russell and Bleach Thomas). He also took important visitors for tours of the trenches. This included David Lloyd George, Georges Clemenceau, George Bernard Shaw and H. G. Wells.

Montague became disillusioned with the First World War. He wrote in his diary in December 1917: "To take part in war cannot, I think, be squared with Christianity. So far the Quakers are right. But I am more sure of my duty of trying to win the war than I am that Christ was right in every part of all that he said, though no one has ever said so much that was right as he did. Therefore I will try, as far as my part goes, to win the war, not pretending meanwhile that I am obeying Christ, and after the war I will try harder than I did before to obey him in all the things in which I am sure he was right. Meanwhile may God give me credit for not seeking to be deceived."

George Bernard Shaw was one of those who Montague took for a tour of the frontline trenches: "At the chateau where the Army entertained the rather mixed lot who were classified as Distinguished Visitors, I met Montague. Finding him just the sort of man I like and get on with, I was glad to learn that he was to be my leader on my excursions. The standing joke about Montague was his craze for being under fire, and his tendency to lead the distinguished visitors, who did not necessarily share this taste into warm corners. Like most standing jokes it was inaccurate, but had something in it.... Both of us felt that, being there, we were wasting our time when we were not within range of the guns. We had come to the theatre to see the play, not to enjoy the intervals between the acts like fashionable people at the opera."

After the war Montague returned to the Manchester Guardian and stayed there until he retired in 1925. He also wrote several books including the novels A Hind Let Loose and Rough Justice, and a collection of essays, Disenchantment (1922) about the First World War. He argued: "The freedom of Europe, The war to end war, The overthrow of militarism, The cause of civilization - most people believe so little now in anything or anyone that they would find it hard to understand the simplicity and intensity of faith with which these phrases were once taken among our troops, or the certitude felt by hundreds of thousands of men who are now dead that if they were killed their monument would be a new Europe not soured or soiled with the hates and greeds of the old. So we had failed - had won the fight and lost the prize; the garland of war was withered before it was gained. The lost years, the broken youth, the dead friends, the women's overshadowed lives at home, the agony and bloody sweat - all had gone to darken the stains which most of us had thought to scour out of the world that our children would live in. Many men felt, and said to each other, that they had been fooled."

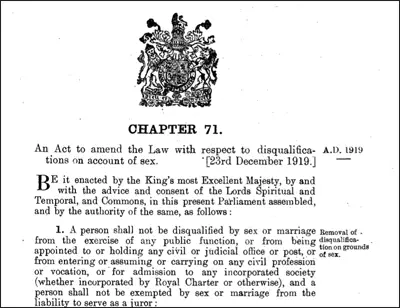

On this day in 1919 the Sex Disqualification Act received Royal Assent. It was now illegal to exclude women from jobs because of their sex. Women could now become solicitors, barristers and magistrates.

On this day in 1993 Lauchlin Currie died of a heart attack in Bogota, Colombia,. Currie was born in 1902 in West Dublin, Canada. His father was a merchant fleet operator and his mother, a schoolteacher. After two years at St. Francis Xavier University in Nova Scotia (1920-1922), he moved to England to study at the London School of Economics (LSE) where he came under the influence of left-wing economists such as Graham Wallas, Hugh Dalton, Richard Tawney and Harold Laski. Currie was also introduced to the theories of John Maynard Keynes.

In 1925 Currie moved to Harvard University. Currie lost most of his and his family’s money in the Wall Street Crash in October 1929. His Ph.D. thesis, Bank Assets and Banking Theories was completed in January 1931. According to Svetlana Chervonnaya, in two articles published in 1933 The Treatment of Credit in Contemporary Monetary Theory and Money, Gold and Incomes in the United States, 1921-32, "Currie stressed the importance of control over the quantity of money, as opposed to the quantity or quality of credit or loans, and computed the first estimate of the income velocity of money in the United States." One of his students was Paul Sweezy.

Marriner Eccles, who worked under the treasury secretary Henry Morgenthau, was greatly influenced by the ideas of Currie, who worked for him as an advisor. Eccles went before the Senate Finance Committee in 1933. According to Patrick Renshaw, the author of Franklin D. Roosevelt (2004): "Though the young Mormon banker from Utah claimed never to have read Keynes he had nevertheless jolted Senate finance committee hearings in 1933 by urging that the federal government forget about trying to balance budgets during the depression and instead spend heavily on relief, public works, the domestic allotment plan and refinancing farm mortgages, while cancelling what remained of war debt."

Lauchlin Currie published The Supply and Control of Money in the United States in 1934. In November, 1934, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Marriner Eccles as Governor of the Federal Reserve Board. As William E. Leuchtenburg, the author of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal (1963), has pointed out: "Eccles had hardly taken office when he helped draft a new banking bill which called for the first radical revision of the Federal Reserve System since its adoption in 1913. Eccles wished to lodge control of the system in the White House; lessen the influence of private bankers, who he believed had taken over the system; and use the Reserve Board as an agency for conscious control of the monetary mechanism. The 20,000-word banking bill introduced in February, 1935, reflected the thinking of Eccles and of certain members of his staff, especially the Keynesian Lauchlin Currie."

In 1935 Currie and Eccles drafted a new banking bill to secure radical reform of the central bank for the first time since the formation of the Federal Reserve Board in 1913. It emphasized budget deficits as a way out of the Great Depression and it was fiercely resisted by bankers and the conservatives in the Senate. The banker, James P. Warburg commented that the bill was: "Curried Keynes... a large, half-cooked lump of J. Maynard Keynes... liberally seasoned with a sauce prepared by professor Lauchlin Currie." With strong support from California bankers eager to undermine New York City domination of national banking, the 1935 Banking Act was passed by Congress.

In July 1939, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Lauchlin Currie as his special adviser on economic affairs and became the first White House economist. On 28th January, 1941, Currie was sent on a mission to Chungking, China to meet Chiang Kai-shek. On his return, Currie recommended that China should be included in the government’s Lend-Lease program. He was put in charge of the program’s administration from 1941 to 1943. He was also involved in setting up the American volunteer air force as the Flying Tigers to fight for China in the war against Japan.

After the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt Currie did not join the Harry S. Truman administration. Instead he established his own import-export business, Lauchlin Currie & Company in New York City. This venture was not very successful and his situation was not helped when Elizabeth Bentley and Whittaker Chambers both claimed that Currie had been part of an espionage ring headed by Nathan Gregory Silvermaster. Currie appeared before the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) on 13th August, 1948. He denied these claims and no criminal charges were ever brought against him.

In 1950 he was asked to head the first of the World Bank’s general country surveys, in Colombia. After is publication he was invited by the Colombian government to return as adviser on implementing the report’s recommendations. He accepted the post and in 1954 married a local woman. Currie was called to appear before the McCarran Committee and when he refused to testify he lost his American citizenship.

The claims of Elizabeth Bentley and Whittaker Chambers were investigated by a former KGB officer, Julius Kobyakov: "I understand that Currie or Harry Dexter White, who were branded as subversives in the McCarthy era and stigmatised again by the VENONA cables, would hardly be considered heroes by the present day American historical establishment. But if a professional opinion is called for, as to whether those people were Soviet agents, my answer is no. It is easy to badmouth the people who no longer can defend themselves, and to overlook the fact that they in their own way may have helped the anti-Hitler coalition to win the bloodiest war in history."