On this day on 16th December

On this day in 1844 Fanny Villard, the daughter of William Lloyd Garrison and Helen Villard, was born. She taught the piano until marrying Henry Villard, the owner of the The Nation. Her son, Oswald Garrison Villard, was born in 1872.

Villard an active supporter of women's rights, joined the American Woman Suffrage Association in 1906. She was also, like her son, Oswald Garrison Villard, a founder member of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP).

A committed pacifist, Villard with Lillian Wald, led a parade of 1200 women down Fifth Avenue in New York on 29th August, 1914 to protest against the First World War. Villard was also a member of the Woman's Peace Party (WPP) and after the war helped establish the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF). Fanny Garrison Villard died on 5th July, 1928.

On this day in 1861 Absalom Watkin died. Watkin, the son of an innkeeper, was born in London. His father died when he was young and at the age of fourteen he accepted the offer of work at his uncle's cotton business in Manchester. John Watkin's small company produced yarn and undyed calico.

A few years after Absalom arrived in Manchester John Watkin sold the business to Thomas Smith. Absalom had done so well since arriving in Manchester that he new owner employed him as the factory manager. Absalom had a strong desire to own his own business and by 1807 had raised enough money to buy the factory from Thomas Smith.

Absalom Watkin was a supporter of parliamentary reform and in 1815 became a member of a group of liberals that used to meet in the home of John Potter. Others in the group included John Edward Taylor, Archibald Prentice, John Shuttleworth, Joseph Brotherton, William Cowdray, Thomas Potter and Richard Potter. The group was strongly influenced by the ideas of Jeremy Bentham and Joseph Priestley and objected to a system that denied such important industrial cities such as Manchester, Leeds and Birmingham, representation in the House of Commons.

All the men held Nonconformist religious views. Absalom Watkin was a Methodist and was a supporter ofJoseph Lancaster and the Nonconformist school that he opened in Manchester in 1813. Watkin, like other members of the group, was an advocate of religious toleration.

Absalom Watkin did not witness the Peterloo Massacre,but he played an important role in the campaign to obtain an independent inquiry into Peterloo. He drew up the famous Declaration and Protest document that was signed by over 5,000 people in Manchester.

After the Peterloo Massacre Absalom Watkin became a close friend of Joseph Johnson, one of the organisers of the meeting at St. Peter's Field. On 12th August 1827 Johnson introduced Watkin to Richard Carlile, the radical journalist who had been one of the main speakers at the Peterloo Massacre. Four days later Absalom carried out a long interview with Richard Carlile about what had happened at St. Peter's Field on 16th August, 1819.

In December 1827, Thomas Potter and John Shuttleworth asked Absalom Watkin if he was interested in taking over from Archibald Prentice as editor of the Manchester Gazette. Although he considered it for several days Watkin eventually turned down the offer.

In December 1830 Absalom Watkin joined a committee of men including Thomas Potter, Mark Philips, William Harvey and William Baxter with the intention of campaigning for parliamentary reform. The group were moderate reformers and did not fully support the demands of the radicals who wanted universal suffrage. Absalom Watkin was given the task of drawing up the petition asking the government to grant Manchester two Members of Parliament.

As a result of the 1832 Reform Act Manchester had its first two Members of Parliament, Mark Philips and Charles Poulett Thomson. Two close friends of Absalom Watkin, Joseph Brotherton (Salford) and Richard Potter (Wigan) also became Members of Parliament in 1832.

Although Absalom Watkin had been in conflict with John Fielden over parliamentary reform, he did agree with his views on factory legislation. In 1833 Absalom Watkin organised the campaign in Manchester for the Ten Hours Bill.

Absalom Watkin's other great concern was over the price of bread. In 1840 he became Vice President of Manchester's Anti-Corn Law League. However, he was strongly opposed to the Chartist campaign and in August 1842 helped the police to defend Manchester from rioters demanding universal suffrage.

Absalom Watkin's two sons also played an active role in politics. Edward Watkin became a Liberal M.P. and Alfred Watkin became Mayor of Manchester.

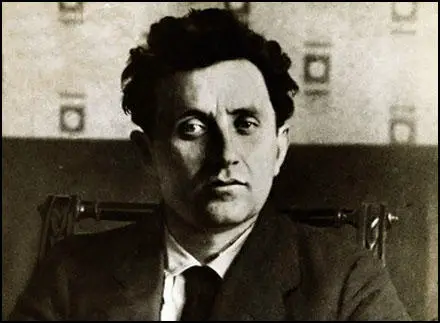

On this day in 1889 Ernst Schmidt, the son of a miller, was born in Wurzbach, Thuringia. After leaving school he became a painter and decorator. He qualified in 1907 and according to his own account he spent his journeyman's time working "in various parts of Germany until 1912, in Switzerland in 1913, in France, and, from the spring of 1914 until the outbreak of war, in Bolzano."

On 6th August, 1914, Schmidt joined the 1st Company of the 16th Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment. Other members of this regiment included Adolf Hitler, Rudolf Hess, Hans Mend and Max Amann. After initial training in Munich Schmidt arrived on the Western Front on 21st October 1914, where his regiment took part in the Battle of Ypres. It has been claimed that Schmidt's regiment was reduced from 3,600 to 611 men during this first period of fighting.

Schmidt was a dispatch-runner with Hitler. Lothar Machtan, the author of The Hidden Hitler (2001) has pointed out: "Employed as regimental runners, they jointly delivered one message with such efficiency - or so we are told - that from November 1914 on they were permanently assigned to regimental headquarters as so-called combat orderlie. As such, they had more freedom within the military hierarchy than other enlisted men.... They were invariably to be seen as a couple, not only when jointly delivering regimental orders to brigade or battalion, but off duty behind the lines." Schmidt told a journalist eighteen years later "I was very much drawn to Hitler".

Hans Mend, a fellow dispatch-runner, has claimed that Schmidt and Hitler had a sexual relationship. "We noticed that he (Hitler) never looked at a woman. We suspected him of homosexuality right away, because he was known to be abnormal in any case. He was extremely eccentric and displayed womanish characteristics which tended in that direction. He never had a firm objective, nor any kind of firm beliefs. In 1915 we were billeted in the Le Febre brewery at Fournes. We slept in the hay. Hitler was bedded down at night with Schmidt, his male whore. We heard a rustling in the hay. Then someone switched on his electric flashlight and growled, Take a look at those two nancy boys. I myself took no further interest in the matter."

Lothar Machtan, the author of The Hidden Hitler (2001) has argued: "Why did Hitler remain a lance corporal throughout the war? His toadying to higher authority, if not his efficiency, should have earned him promotion. We are told that he was offered it but refused. It would probably be more correct to say that he could not bring himself to accept. As a noncom he would sooner or later have been obliged to give up what had hitherto enabled him to tolerate war service so well: Ernst Schmidt, his other faithful partners, a relatively safe existence in the rear echelon, and possibly also, a toleration of the homosexual tendencies he could not have pursued as a noncommissioned officer."

Schmidt's regiment was at the Battle of the Somme and on 2nd October 1916, he was wounded when a shell exploded in the dispatch runners' dug-out, killing and wounding several of them. Hitler was wounded in the left thigh and spent almost two months in the Red Cross hospital at Beelitz, near Berlin. In January, 1917, Hitler wrote to the regiment's adjutant, Fritz Wiedemann, for permission to return "to the 16th Reserve Infantry Regiment" and serve with his "former comrades". Hitler also wrote to Sergeant Max Amann to see if he could use his influence to be reassigned to his regiment, his "elective family". Hitler later recalled that his regiment had taught him "the glorious meaning of a male community". Hitler was allowed rejoin his regiment in March 1917.

In October 1918, Hitler was blinded in a British mustard gas attack. Hitler wrote in Mein Kampf (1925): "On a hill south of Werwick, in the evening of October 13th, we were subjected for several hours to a heavy bombardment with gas bombs, which continued throughout the night with more or less intensity. About midnight a number of us were put out of action, some for ever. Towards morning I also began to feel pain. It increased with every quarter of an hour; and about seven o’clock my eyes were scorching as I staggered back and delivered the last dispatch I was destined to carry in this war. A few hours later my eyes were like glowing coals and all was darkness around me."

Hitler was sent to a military hospital and gradually recovered his sight. While he was in hospital Germany surrendered. "Everything went black before my eyes; I tottered and groped my way back to the ward, threw myself on my bunk, and dug my burning head into my blanket and pillow. So it had all been in vain. In vain all the sacrifices and privations; in vain the hours in which, with mortal fear clutching at our hearts, we nevertheless did our duty; in vain the death of two million who died. Had they died for this? Did all this happen only so that a gang of wretched criminals could lay hands on the Fatherland. I knew that all was lost. Only fools, liars and criminals could hope for mercy from the enemy. In these nights hatred grew in me, hatred for those responsible for this deed. Miserable and degenerate criminals! The more I tried to achieve clarity on the monstrous events in this hour, the more the shame of indignation and disgrace burned my brow." Hitler went into a state of deep depression, and had periods when he could not stop crying. He spent most of his time turned towards the hospital wall refusing to talk to anyone. Once again Hitler's efforts had ended in failure.

At the end of the war Schmidt returned to Munich. In early 1919 Schmidt met up with Hitler and they worked together as casual labourers. According to Schmidt they also attended the opera in the city: "We only bought the cheapest seats, but that didn't matter. Hitler was lost in the music to the very last note; blind and deaf to all else around him." Schmidt also pointed out that Hitler had not yet given up hope of being an artist. During this period he made contact with the well-known artist, Max Zaeper, to whom he "gave several of his works for expert appraisal".

Hans Mend, who served with Schmidt and Hitler, during the First World War, told Friedrich Alfred Schmid Noerr that he saw the men together several times. "I met Adolf Hitler again at the end of 1918. I bumped into him on the Marienplatz in Munich, where he was standing with his friend Ernst Schmidt.... Hitler was then living in a hostel for the homeless at 29 Lothstrasse, Munich. Soon afterward, having camped at my apartment for several days, he took refuge at Traunstein barracks because he was hungry. He managed to get by, as he often did in the future, with the help of his Iron Cross 1st Class and his gift of the gab. In January 1919 I again ran into Hitler at the newsstand on Marienplatz. Then, one evening, while I was sitting in the Rathaus Cafe with a girl, Hitler and his friend Ernst Schmidt came in." Mend claimed that after the two men left his girlfriend told him: "If you're friendly with people like that, I'm not going out with you anymore."

Schmidt shared Hitler's right-wing political opinions and in March, 1920, he joined the German Worker's Party (GWP). In 1922 Schmidt moved to Garching an der Alz, over sixty miles from Munich. He kept in constant touch with Hitler and visited him in May 1924 when he was imprisoned in Landsberg Castle. He also founded a local branch of the Nazi Party. On 1st May, 1925, Hitler sent him a gilt-edged copy of Mein Kampf that was inscribed to my "dear and faithful wartime comrade".

In 1931 Schmidt joined the Sturmabteilung (SA) as a Scharführer (staff sergeant) and rose to the rank Sturmführer (captain). In 1932, when Hitler's political opponents distributed smear stories about him, Schmidt swore several affidavits in his friend's defence. Hitler rewarded Schmidt generously for his loyalty and discretion and he was able to build himself a large house in Garching. He also invested heavily in his building business and purchased an automobile, which was the main symbol of social advancement at the time.

Ernst Schmidt often visited the Reich Chancellery and in 1934 he was awarded the Party's gold badge. Hitler still used Schmidt to promote his image as a brave soldier during the First World War. In 1937 the Illustrierter Beobachter published an article about "Adolf Hitler and his front-line comrade" and quoted Schmidt as saying: "If the Führer ever summoned me to perform some special task, I should abandon my job and everything else, and follow him."

In December 1939, Hans Mend was interviewed by Friedrich Alfred Schmid Noerr, a member of the German Resistance. Mend insisted that Schmidt and Hitler had a homosexual relationship during the war. Soon afterwards Mend was arrested and charged with various sexual offences against women. He was sentenced by a special court to two years' imprisonment. According to the prison authorities Mend died in Zwickau Penitentiary on 13th February, 1942.

Schmidt became mayor of Garching and in 1942 was appointed as district head of the National Socialist German Workers Party. After the war he was arrested by the allies and imprisoned. In his denazification hearing in 1948 Schmidt he admitted that he had been the victim of several blackmail attempts concerning his relationship with Hitler. He referred to a man named Philipp Oberbuchner who had written several "anonymous letters of malicious content" but had "refrained from preferring charges". Ernst Schmidt died in 1985.

On this day in 1911 the National Insurance Act received royal assent. During his speech on the People's Budget, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George, pointed out that Germany had a compulsory national insurance against sickness since 1884. He argued that he intended to introduce a similar system in Britain. With a reference to the arms race between Britain and Germany he commented: "We should not emulate them only in armaments."

In the autumn of 1908 Winston Churchill advocated the introduction of unemployment insurance. The scheme was restricted to trades which suffered from cyclical unemployment (shipbuilding, engineering and construction) and excluded those in decline, those with a large amount of casual labour and those with substantial short-time working (such as mining and cotton spinning). It would cover only about two million workers. The plan was that employees would contribute twice as much per week as the State and employers. The benefit would only be paid for a maximum of fifteen weeks and at a low enough rate to "imply a sensible and even severe difference between being in work or out of work."

In April 1909, Churchill presented the draft Bill to the Cabinet. Employer and State contributions had increased but benefits had decreased and were to be calculated on a stiff sliding-scale over the fifteen weeks so that so that, as Churchill told fellow ministers, "an increasing pressure is put on the recipient of benefit to find work". The Cabinet was divided over the issue. Some like David Lloyd George wanted a more generous and more wide-ranging scheme and he took over responsibility of introducing a national insurance scheme.

In December 1910 Lloyd George sent one of his Treasury civil servants, William J. Braithwaite, to Germany to make an up-to-date study of its State insurance system. On his return he had a meeting with Charles Masterman, Rufus Isaacs and John S. Bradbury. Braithwaite argued strongly that the scheme should be paid for by the individual, the state and the employer: "Working people ought to pay something. It gives them a feeling of self respect and what costs nothing is not valued."

One of the questions that arose during this meeting was whether British national insurance should work, like the German system, on the "dividing-out" principle, or should follow the example of private insurance in accumulating a large reserve. Lloyd George favoured the first method, but Braithwaite fully supported the alternative system. He argued: "If a fund divides out, it is a state club, and not an insurance. It has no continuity - no scientific basis - it lives from day to day. It is all very well when it is young and sickness is low. But as its age increases sickness increases, and the young men can go elsewhere for a cheaper insurance." Lloyd George replied: "Why accumulate a fund? The State could not manage property or invest with wisdom. It would be very bad for politics if the State owned a huge fund."

The debate between the two men continued over the next two months. Lloyd George argued: "The State could not manage property or invest with wisdom. It would be very bad for politics if the State owned a huge fund. The proper course for the Chancellor of the Exchequer was to let money fructify in the pockets of the people and take it only when he wanted it."

Eventually, in March, 1911, Braithwaite produced a detailed paper on the subject, where he explained that the advantage of a state system was the effect of interest on accumulative insurance. Lloyd George told Braithwaite that he had read his paper but admitted he did not understand it and asked him to explain the economics of his health insurance system.

"I managed to convince him that one way or another it (interest) was, and had to be paid. It was at any rate an extra payment which young contributors could properly demand, and the State contribution must at least make it up to them if their contributions were to be taken off and used by the older people. After about half an hour's talk he went upstairs to dress for dinner." Later that night Lloyd George told Braithwaite that he was now convinced by his proposals. "Dividing-out was dead!"

Braithwaite explained that the advantages of an accumulative state fund was the ability to use the insurance reserve to underwrite other social programmes. Lloyd George presented his national insurance proposal to the Cabinet at the beginning of April. "Insurance was to be made compulsory for all regularly employed workers over the age of sixteen and with incomes below the level - £160 a year - of liability for income tax; also for all manual labourers, whatever their income. The rates of contribution would be 4d. a week from a man, and 3d. a week from a woman; 3d. a week from his or her employer; and 2d. a week from the State."

The slogan adopted by Lloyd George to promote the scheme was "9d for 4d". In return for a payment which covered less than half the cost, contributors were entitled to free medical attention, including the cost of medicine. Those workers who contributed were also guaranteed 10s. a week for thirteen weeks of sickness and 5s a week indefinitely for the chronically sick.

Braithwaite later argued that he was impressed by the way Lloyd George developed his policy on health insurance: "Looking back on these three and a half months I am more and more impressed with the Chancellor's curious genius, his capacity to listen, judge if a thing is practicable, deal with the immediate point, deferring all unnecessary decision and keeping every road open till he sees which is really the best. Working for any other man I must inevitably have acquiesced in some scheme which would not have been as good as this one, and I am very glad now that he tore up so many proposals of my own and other people which were put forward as solutions, and which at the time we had persuaded ourselves into thinking possible. It will be an enormous misfortune if this man by any accident should be lost to politics."

The large insurance companies were worried that this measure would reduce the popularity of their own private health schemes. David Lloyd George, arranged a meeting with the association that represented the twelve largest companies. Their chief negotiator was Kingsley Wood, who told Lloyd George, that in the past he had been able to muster enough support in the House of Commons to defeat any attempt to introduce a state system of widows' and orphans' benefits and so the government "would be wise to abandon the scheme at once."

David Lloyd George was able to persuade the government to back his proposal of health insurance: "After searching examination, the Cabinet expressed warm and unanimously approval of the main and government principles of the scheme which they believed to be more comprehensive in its scope and more provident and statesmanlike in its machinery than anything that had hitherto been attempted or proposed."

The National Insurance Bill was introduced into the House of Commons on 4th May, 1911. Lloyd George argued: "It is no use shirking the fact that a proportion of workmen with good wages spend them in other ways, and therefore have nothing to spare with which to pay premiums to friendly societies. It has come to my notice, in many of these cases, that the women of the family make most heroic efforts to keep up the premiums to the friendly societies, and the officers of friendly societies, whom I have seen, have amazed me by telling the proportion of premiums of this kind paid by women out of the very wretched allowance given them to keep the household together."

Lloyd George went on to explain: "When a workman falls ill, if he has no provision made for him, he hangs on as long as he can and until he gets very much worse. Then he goes to another doctor (i.e. not to the Poor Law doctor) and runs up a bill, and when he gets well he does his very best to pay that and the other bills. He very often fails to do so. I have met many doctors who have told me that they have hundreds of pounds of bad debts of this kind which they could not think of pressing for payment of, and what really is done now is that hundreds of thousands - I am not sure that I am not right in saying millions - of men, women and children get the services of such doctors. The heads of families get those services at the expense of the food of their children, or at the expense of good-natured doctors."

Lloyd George stated this measure was just the start to government involvement in protecting people from social evils: "I do not pretend that this is a complete remedy. Before you get a complete remedy for these social evils you will have to cut in deeper. But I think it is partly a remedy. I think it does more. It lays bare a good many of those social evils, and forces the State, as a State, to pay attention to them. It does more than that... till the advent of a complete remedy, this scheme does alleviate an immense mass of human suffering, and I am going to appeal, not merely to those who support the Government in this House, but to the House as a whole, to the men of all parties, to assist us."

The Observer welcome the legislation as "by far the largest and best project of social reform ever yet proposed by a nation. It is magnificent in temper and design". The British Medical Journal described the proposed bill as "one of the greatest attempts at social legislation which the present generation has known" and it seemed that it was "destined to have a profound influence on social welfare."

Ramsay MacDonald promised the support of the Labour Party in passing the legislation, but some MPs, including Fred Jowett, George Lansbury and Philip Snowden denounced it as a poll tax on the poor. Along with Keir Hardie, they wanted free sickness and unemployment benefit to be paid for by progressive taxation. Hardie commented that the attitude of the government was "we shall not uproot the cause of poverty, but we will give you a porous plaster to cover the disease that poverty causes."

Lloyd George's reforms were strongly criticised and some Conservatives accused him of being a socialist. There was no doubt that he had been heavily influenced by Fabian Society pamphlets on social reform that had been written by Beatrice Webb, Sidney Webb and George Bernard Shaw. However, some Fabians "feared that the Trade Unions might now be turned into Insurance Societies, and that their leaders would be further distracted from their industrial work."

Lloyd George pointed out that the labour movement in Germany had initially opposed national insurance: "In Germany, the trade union movement was a poor, miserable, wretched thing some years ago. Insurance has done more to teach the working class the virtue of organisation than any single thing. You cannot get a socialist leader in Germany today to do anything to get rid of that Bill... Many socialist leaders in Germany will say that they would rather have our Bill than their own."

Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe, launched a propaganda campaign against the bill on the grounds that the scheme would be too expensive for small employers. The climax of the campaign was a rally in the Albert Hall on 29th November, 1911. As Lord Northcliffe, controlled 40 per cent of the morning newspaper circulation in Britain, 45 per cent of the evening and 15 per cent of the Sunday circulation, his views on the subject was very important.

H. H. Asquith was very concerned about the impact of the The Daily Mail involvement in this issue: "The Daily Mail has been engineering a particularly unscrupulous campaign on behalf of mistresses and maids and one hears from all constituencies of defections from our party of the small class of employers. There can be no doubt that the Insurance Bill is (to say the least) not an electioneering asset."

Frank Owen, the author of Tempestuous Journey: Lloyd George and his Life and Times (1954) suggested that it was those who employed servants who were the most hostile to the legislation: "Their tempers were inflamed afresh each morning by Northcliffe's Daily Mail, which alleged that inspectors would invade their drawing-rooms to check if servants' cards were stamped, while it warned the servants that their mistresses would sack them the moment they became liable for sickness benefit."

The National Insurance Bill spent 29 days in committee and grew in length and complexity from 87 to 115 clauses. These amendments were the result of pressure from insurance companies, Friendly Societies, the medical profession and the trade unions, which insisted on becoming "approved" administers of the scheme. The bill was passed by the House of Commons on 6th December and received royal assent on 16th December 1911.

Lloyd George admitted that he had severe doubts about the amendments: "I have been beaten sometimes, but I have sometimes beaten off the attack. That is the fortune of war and I am quite ready to take it. Honourable Members are entitled to say that they have wrung considerable concessions out of an obstinate, stubborn, hard-hearted Treasury. They cannot have it all their own way in this world. Let them be satisfied with what they have got. They are entitled to say this is not a perfect Bill, but then this is not a perfect world. Do let them be fair. It is £15,000,000 of money which is not wrung out of the workmen's pockets, but which goes, every penny of it, into the workmen's pocket. Let them bear that in mind. I think they are right in fighting for organisations which have achieved great things for the working classes. I am not at all surprised that they regard them with reverence. I would not do anything which would impair their position. Because in my heart I believe that the Bill will strengthen their power is one of the reasons why I am in favour of this Bill."

The Daily Mail and The Times, both owned by Lord Northcliffe, continued its campaign against the National Insurance Act and urged its readers who were employers not to pay their national health contributions. David Lloyd George asked: "Were there now to be two classes of citizens in the land - one class which could obey the laws if they liked; the other, which must obey whether they liked it or not? Some people seemed to think that the Law was an institution devised for the protection of their property, their lives, their privileges and their sport it was purely a weapon to keep the working classes in order. This Law was to be enforced. But a Law to ensure people against poverty and misery and the breaking-up of home through sickness or unemployment was to be optional."

David Lloyd George attacked the newspaper baron for encouraging people to break the law and compared the issue to the foot-and-mouth plague rampant in the countryside at the time: "Defiance of the law is like the cattle plague. It is very difficult to isolate it and confine it to the farm where it has broken out. Although this defiance of the Insurance Act has broken out first among the Harmsworth herd, it has travelled to the office of The Times. Why? Because they belong to the same cattle farm. The Times, I want you to remember, is just a twopenny-halfpenny edition of The Daily Mail."

Despite the opposition from newspapers and and the British Medical Association, the business of collecting contributions began in July 1912, and the payment of benefits on 15th January 1913. Lloyd George appointed Sir Robert Morant as chief executive of the health insurance system. William J. Braithwaite was made secretary to the joint committee responsible for initial implementation, but his relations with Morant were deeply strained. "Overworked and on the verge of a breakdown, he was persuaded to take a holiday, and on his return he was induced to take the post of special commissioner of income tax in 1913."

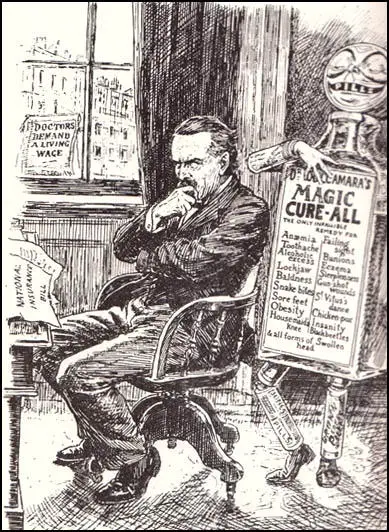

Patent Medicine: "Never mind, dear fellow, I'll stand by you - to the death!"

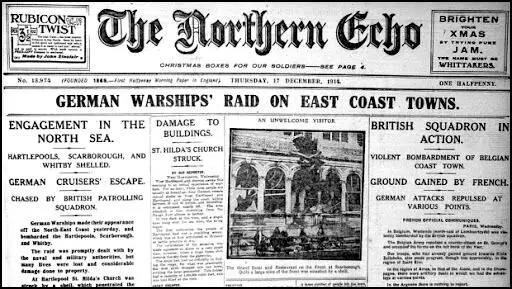

On this day in 1914 Admiral Franz von Hipper commands a raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby. In December 1914 the Germans bombarded the costal towns. The attack caused more than 700 casualties, including 137 people killed, mostly civilians. It created a great deal of anger against Germany and the Royal Navy for failing to protect the British coast. It was clear that naval enthusiasts, especially British ones, were not going to have the war they had expected.

On this day in 1934 Gregory Zinoviev writes a letter to Joseph Stalin pleading his innocence. Zinoviev was arrested after the assassination of Sergey Kirov on 1st December. Leonid Nikolayev was immediately arrested and after being tortured by Genrikh Yagoda he signed a statement saying that Zinoviev, Leon Trotsky and Lev Kamenev had been the leaders of the conspiracy to assassinate Kirov.

Zinoviev wrote to Stalin: "I tell you, Comrade Stalin, honesty, that from the time of my return from Kustanai by order of the Central Committee, I have not taken a single step, spoken a single word, written a single line, or had a single thought which I need conceal from the Party, the Central Committee, and you personally... I have had only one thought - how to earn the trust of the Central Committee and you personally, how to achieve my aim of being employed by you in the work there is to be done. I swear by all a Bolshevik holds sacred, I swear by Lenin's memory... I implore you to believe my word of honor."

According to Alexander Orlov: "Stalin decided to arrange for the assassination of Kirov and to lay the crime at the door of the former leaders of the opposition and thus with one blow do away with Lenin's former comrades. Stalin came to the conclusion that, if he could prove that Zinoviev and Kamenev and other leaders of the opposition had shed the blood of Kirov". Victor Kravchenko has pointed out: "Hundreds of suspects in Leningrad were rounded up and shot summarily, without trial. Hundreds of others, dragged from prison cells where they had been confined for years, were executed in a gesture of official vengeance against the Party's enemies. The first accounts of Kirov's death said that the assassin had acted as a tool of dastardly foreigners - Estonian, Polish, German and finally British. Then came a series of official reports vaguely linking Nikolayev with present and past followers of Trotsky, Zinoviev, Kamenev and other dissident old Bolsheviks."

Leonid Nikolayev was executed after his trial but Zinoviev and Kamenev refused to confess. Ya S. Agranov, the deputy commissar of the secret police, reported to Stalin he was not able to prove that they had been directly involved in the assassination. Therefore in January 1935 they were tried and convicted only for "moral complicity" in the crime. "That is, their opposition had created a climate in which others were incited to violence." Zinoviev was sentenced to ten years hard labour, Kamenev to five.

Genrikh Yagoda now had the task of persuading Kamenev and Zinoviev to confess to their role in the death of Kirov as part of the plot to assassinate Stalin and other leaders of government. When they refused to do this Stalin had a new provision enacted into law on 8th April 1935 which would enable him to exert additional leverage over his enemies. The new law decreed that children of the age of twelve and over who were found guilty of crimes would be subjected to the same punishment as adults, up to and including the death penalty. This provision provided NKVD with the means by which they could coerce a confession from a political dissident simply by claiming that false charges would be brought against their children.

Edward P. Gazur, the author of Alexander Orlov: The FBI's KGB General (2001), claims that Alexander Orlov later admitted: "In the months preceding the trial, the two men were subjected to every conceivable form of interrogation: subtle pressure, then periods of enormous pressure, starvation, open and veiled threats, promises, as well as physical and mental torture. Neither man would succumb to the ordeal they faced." Stalin was frustrated by Stalin's lack of success and brought in Nikolai Yezhov to carry out the interrogations.

Orlov, who was a leading figure in the NKVD, later admitted what happened. "Towards the end of their ordeal, Zinoviev became sick and exhausted. Yezhov took advantage of the situation in a desperate attempt to get a confession. Yezhov warned that Zinoviev must affirm at a public trial that he had plotted the assassination of Stalin and other members of the Politburo. Zinoviev declined the demand. Yezhov then relayed Stalin's offer; that if he co-operated at an open trial, his life would be spared; if he did not, he would be tried in a closed military court and executed, along with all of the opposition. Zinoviev vehemently rejected Stalin's offer. Yezhov then tried the same tactics on Kamenev and again was rebuffed."

In July 1936 Yezhov told Gregory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev that their children would be charged with being part of the conspiracy and would face execution if found guilty. The two men now agreed to co-operate at the trial if Joseph Stalinpromised to spare their lives. At a meeting with Stalin, Kamenev told him that they would agree to co-operate on the condition that none of the old-line Bolsheviks who were considered the opposition and charged at the new trial would be executed, that their families would not be persecuted, and that in the future none of the former members of the opposition would be subjected to the death penalty. Stalin replied: "That goes without saying!"

The trial opened on 19th August 1936. Five of the sixteen defendants were actually NKVD plants, whose confessional testimony was expected to solidify the state's case by exposing Zinoviev, Kamenev and the other defendants as their fellow conspirators. The presiding judge was Vasily Ulrikh, a member of the secret police. The prosecutor was Andrei Vyshinsky, who was to become well-known during the Show Trials over the next few years.

Yuri Piatakov accepted the post of chief witness "with all my heart." Max Shachtman pointed out: "The official indictment charges a widespread assassination conspiracy, carried on these five years or more, directed against the head of the Communist party and the government, organized with the direct connivance of the Hitler regime, and aimed at the establishment of a Fascist dictatorship in Russia. And who are included in these stupefying charges, either as direct participants or, what would be no less reprehensible, as persons with knowledge of the conspiracy who failed to disclose it?"

The men made confessions of their guilt. Lev Kamenev said: "I Kamenev, together with Zinoviev and Trotsky, organised and guided this conspiracy. My motives? I had become convinced that the party's - Stalin's policy - was successful and victorious. We, the opposition, had banked on a split in the party; but this hope proved groundless. We could no longer count on any serious domestic difficulties to allow us to overthrow. Stalin's leadership we were actuated by boundless hatred and by lust of power."

Gregory Zinoviev also confessed: "I would like to repeat that I am fully and utterly guilty. I am guilty of having been the organizer, second only to Trotsky, of that block whose chosen task was the killing of Stalin. I was the principal organizer of Kirov's assassination. The party saw where we were going, and warned us; Stalin warned as scores of times; but we did not heed these warnings. We entered into an alliance with Trotsky."

Kamenev's final words in the trial concerned the plight of his children: "I should like to say a few words to my children. I have two children, one is an army pilot, the other a Young Pioneer. Whatever my sentence may be, I consider it just... Together with the people, follow where Stalin leads." This was a reference to the promise that Stalin made about his sons.

On 24th August, 1936, Vasily Ulrikh entered the courtroom and began reading the long and dull summation leading up to the verdict. Ulrikh announced that all sixteen defendants were sentenced to death by shooting. Edward P. Gazur has pointed out: "Those in attendance fully expected the customary addendum which was used in political trials that stipulated that the sentence was commuted by reason of a defendant's contribution to the Revolution. These words never came, and it was apparent that the death sentence was final when Ulrikh placed the summation on his desk and left the court-room." The following day Soviet newspapers carried the announcement that all sixteen defendants had been put to death.

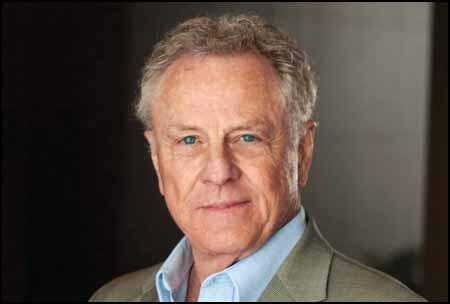

On this day in 1936 Morris Dees, the son of a cotton gin operator, was born at Shorter, Alabama. After graduating from the University of Alabama School of Law (1960) he moved to Montgomery where he established a mail order and book publishing business,.

In 1967 Dees decided to sell his successful business and become a specialist civil rights lawyer. He soon developed a reputation for supporting the cause of African Americans. This included campaigning against the building of a new university in Alabama for white students and for the integration of the all-white Montgomery YMCA.

In 1971 Dees joined with Joseph J. Levin and Julian Bond to establish the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) in Montgomery, Alabama. A non-profit organization, the SPLC attempts to "combat hate, intolerance, and discrimination through education and litigation." The SPLC initially provided legal representation in individual cases dealing with racial discrimination.

After the lynching of Michael Donald in 1981, the SPLC represented his mother, Beulah Mae Donald, in a civil suit which resulted in a $7 million liability judgment which bankrupted the United Klans of America.

Dees was given the Roger Baldwin Award by the American Civil Liberties Union in 1990. Dees has published several books including A Season for Justice (1991), Hate on Trial: The Case Against America's Most Dangerous Neo-Nazi (1993), Gathering Storm: America's Militia Threat (1996) and A Lawyer's Journey: The Morris Dees Story (2003).

On this day in 1964 Mary Sophia Allen died. Mary the daughter of the manager of the Great Western Railway, was born in Cardiff on 12th March, 1878. Educated at Princess Helena College in Ealing, she joined the Women's Political and Social Union (WSPU) after meeting Annie Kenney. Her father gave her an ultimatum to either give up her involvement in the suffragette movement or to leave the house. She left but her father continued to support her financially.

In February 1909 she was a member of the WSPU deputation to the House of Commons. She was one of the 28 women arrested and was sentenced to a month's imprisonment in Holloway. On her release she was appointed as WSPU organiser in Cardiff.

During the summer of 1908 the WSPU introduced the tactic of breaking the windows of government buildings. On 30th June suffragettes marched into Downing Street and began throwing small stones through the windows of the Prime Minister's house. As a result of this demonstration, twenty-seven women were arrested and sent to Holloway Prison. This included Mary Allen.

Marion Wallace-Dunlop was a fellow prisoner. Christabel Pankhurst later reported: "Miss Wallace Dunlop, taking counsel with no one and acting entirely on her own initiative, sent to the Home Secretary, Mr. Gladstone, as soon as she entered Holloway Prison, an application to be placed in the first division as befitted one charged with a political offence. She announced that she would eat no food until this right was conceded." She refused to eat for several days. Afraid that she might die and become a martyr, it was decided to release her after fasting for 91 hours. Soon afterwards other imprisoned suffragettes, including Mary Allen, adopted the same strategy. Unwilling to release all the imprisoned suffragettes, the prison authorities force-fed these women on hunger strike.

In August 1909 she received a hunger-strike medal from Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence. According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999), she was the first woman to be awarded this medal. In November 1909 she was arrested for breaking the windows of the Bristol Liberal Club during a visit made by Winston Churchill. She was sentenced to two weeks' imprisonment and after going on hunger strike she was forcibly fed.

Grace Roe remarked that at this time Mary Allen was "very feminine, very delicate". Mary Allen recalled that her digestion had been permanently affected and she was forbidden by Emmeline Pankhurst to take part in any further militant activity.

In February 1912 she became organizer of the Hastings branch of the WSPU and in early 1914 she replaced Lucy Burns as organizer in Edinburgh. On 6th May Christabel Pankhurst wrote to Janie Allan that "in Edinburgh a small handful of people... are decidedly cantankerous, and the person who is organising for the time being is made to feel the effect of this. These people criticise Miss Mary Allen."

Like most members of the WSPU, Allen agreed to the decision to give full support to the British war effort during the First World War. According to Joan Lock, the author of The British Policewoman (1979): "She (Mary Allen) was invited to join a needlework guild, a prospect which filled her with horror: she wanted action. While in this state of limbo, she overheard two people on a bus discussing the risible idea of women police. Mary was enchanted by the notion and immediately investigated and volunteered.

In September 1914, Nina Boyle founded the Women Police Volunteers. The following year Margaret Damer Dawson became Commandant and Allen became Sub-Commandant. Allen argued that it was her experience in the WSPU that made her realise how necessary it was that women when arrested should not "be handled by men."

The government had always opposed the idea of police women but with large numbers of policemen joining the British Army, it was considered a good idea to have women volunteers to help run the service. Another reason that Dawson's proposal was accepted was that her members were willing to work without pay.

Allen later remarked in her book, The Pioneer Policewoman, that: "A sense of humour had kept me from any bitterness. I was quite as enthusiastically ready to work with and for the police as I had been prepared, if necessary, to enter into combat with them."

In February 1915 Allen and Margaret Damer Dawson renamed her organisation, the Women's Police Service (WPS). At first the WPS concentrated its work in the London area. Wearing a dark-blue uniform, the WPS were assigned responsibilities such as looking after the welfare of refugees. Later that year, Allen was sent to sort out problems in Grantham and Hull. Both towns had army camps and local people were complaining about drunken behaviour and a growth in prostitution.

According to Rebecca Jennings, the author of A Lesbian History of Britain (2007): "Mary Allen's enthusiasm was shared by Margaret Damer Dawson, and the two soon established a close professional and personal relationship, living together in London between 1914 and 1920."

When the Armistice was signed, there were 357 members of the Women's Police Service. Margaret Damer Dawson and Allen, asked the Chief Commissioner, Sir Nevil Macready, to make them a permanent part of his force. He refused, saying that the women were "too educated" and would "irritate" male members of the force. Macready instead decided to recruit and train his own women. However, both Dawson and Allen were awarded the OBE for services to their country during wartime.

When ill-health forced Margaret Damer Dawson to retire in 1920, Allen became the new Commandant of the Women Police Service. In February, 1920, Mary Allen and four of her members were charged with "impersonating police officers". It was claimed that their uniforms were too similar to that of the one worn by the Metropolitan Women Police Patrols. After a four-day hearing Macready won his case and the WPS were forced to change its uniform and its name to the Women's Auxiliary Service.

Rebecca Jennings has argued that: "When Dawson died in 1920, Allen was a major beneficiary in her will, continuing to live in Dawson's house, Danehill, throughout the 1930s and beginning a relationship in the early 1920s with another former WPS officer Miss Helen Tagart."

In 1922 Allen spent time in Cologne where she trained German women for police work. During the 1926 General Strike she helped to keep the road transport services running. According to her biographer, Vera Di Campli San Vito: "In 1927 she founded and edited the Policewoman's Review, which ran until 1937. It was here, in December 1933, that she advertised for recruits to her newly formed women's reserve, the object of which was to train women for service in any national emergency."

Allen was a frequent visitor to Nazi Germany and after meeting Adolf Hitler in 1934 and became one of his most fervent admirers. In a discussion with Hermann Goering she was very pleased when he said that policewomen should wear uniform. Even when on official duties with the Women's Auxiliary Service she wore Nazi style jack-boots.

Allen was an active supporter of General Francisco Franco and his Nationalist Army during the Spanish Civil War. She was also Chief Women's Officer of the British Union of Fascists (BUF) and a member of the the Right-Club. The historian, Julie V. Gottlieb, has argued: "Allen was a prominent supporter of Mosley's British Union, a movement she claimed she had joined due to her sympathy for its anti-war policy." In 1940 she contributed a series of articles for Action, the organ of the BUF.

Her extreme right-wing views made her unpopular with some members of the Women's Auxiliary Service and she was forced to leave the movement with the approach of the Second World War. According to Helena Wojtczak: "Mary Allen became increasingly eccentric, and her apparent support for Hitler and Goering led to questions about whether she should be interned in 1940." Although she was not interned, her membership of the British Union of Fascists resulted in a suspension order under defence regulation 18B on 11th July 1940.

Mary Allen, who wrote several books, including The Pioneer Policewoman (1925), Woman at the Crossroads (1934) and Lady in Blue (1936), died in the Birdhurst Nursing Home, 4 Birdhurst Road, Croydon, of cerebral thrombosis and cerebral arteriosclerosis on 16th December 1964.

On this day in 1996 artist Quentin Bell died at his home, 81 Heighton Street, Firle, East Sussex. Bell, the younger son of Clive Heward Bell and his wife, Vanessa Bell, the daughter of Leslie Stephen, and the sister of Virginia Woolf, was born on 19th August 1910. He was brought up in the family home at 46 Gordon Square and at Charleston Farmhouse. Like his brother, Julian Bell, he was educated at Leighton Park School, the Quaker boarding-school in Reading. A talented artist, Bell left school at seventeen and went on a tour of central European galleries with Roger Fry, the famous art critic. He spent periods of time painting in both Paris and Rome.

In 1933 Bell was forced to spend seven months in a sanatorium in Switzerland followed by convalescence near Monaco. In 1935 he returned to Italy and had his first exhibition at the Mayor Gallery. But later that year he decided to become a potter rather than a painter and enrolled himself at Burslem School of Art. While living in Stoke-on-Trent he became an active member of the Labour Party. Eventually he set up a studio at Charleston Farmhouse, where his artist mother Vanessa Bell and her former lover, Duncan Grant, also worked.

According to Leonard Woolf, Bell became a member of the Bloomsbury Group: "in the 1920's and 1930's when Old Bloomsbury narrowed and widened into a newer Bloomsbury, it lost through death Lytton (Strachey) and Roger (Fry) and added to its numbers, Julian, Quentin and Angelica Bell, and David (Bunny) Garnett."

Bell's parents had been pacifists during the First World War. Bell was willing to joined the British Army after the outbreak of the Second World War but as was in poor health he was rejected on medical grounds. He therefore worked on the farm owned by John Maynard Keynes near Firle. He also joined his mother Vanessa Bell and her former lover, Duncan Grant, in providing wall-paintings at Berwick Church, that were completed in 1943. He was also employed by David Garnett in the political warfare department of the Foreign Office.

In 1947 Bell published his first major book, On Human Finery, a study of the history of fashion. He married the art historian, Anne Olivier Popham, on 16th February 1952. Soon afterwards he became a senior lecturer at King's College, Newcastle upon Tyne. He moved to Leeds Art School in 1959. He also taught at Slade Art School and Hull Art School before in 1967 becoming professor of the history and theory of art at Sussex University.

Bell had been a member of the Bloomsbury Circle, a group that included Virginia Woolf, Vanessa Bell , Clive Bell, John Maynard Keynes, Adrian Stephen, E. M. Forster, Leonard Woolf, Lytton Strachey, Desmond MacCarthy, Mary MacCarthy, Duncan Grant, and Saxon Sydney-Turner. He was therefore in a good position to publish Bloomsbury (1968) and a two volume biography of his aunt, in his much acclaimed Virginia Woolf: A Biography (1972).

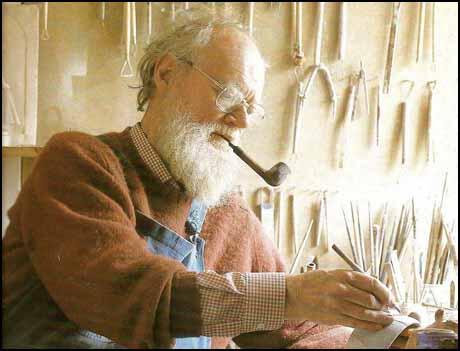

According to his biographer, Charles Saumarez Smith: "After retiring from his post at Sussex in 1975, Bell was able to spend more time and energy on his pottery. In 1985 he and his wife, Olivier, moved to a smaller house next door to the park in Firle and each morning he would wake up early and disappear to his kiln, only emerging for gin and ginger beer in the evening. He undertook a mixture of work, some rough, painted plates and mugs, which he saw as belonging to an artisan tradition, but also more ambitious ceramic sculpture. Neither style fitted comfortably within the work of contemporaries, as his pots were too utilitarian to be regarded as art and his ceramic sculpture too conventionally figurative. But this in no way deterred him from turning out a great amount of work which was both vigorous and affordable, a crossover between the Omega workshop and folk art."

Quentin Bell helped establish the Charleston Trust, which was responsible for saving his mother's house. Other books included a novel, The Brandon Papers (1985), a collection of essays and lectures in Bad Art (1989), and a series of character sketches, Elders and Betters (1995).