Michael Donald

Michael Donald was born in Mobile, Alabama, in 1962. He attending a local trade school and worked part-time at the Mobile Press Register.

In 1981 the trial of Josephus Andersonan, an African American charged with the murder of a white policeman, took place in Mobile. At the end of the case the jury was unable to reach a verdict. This upset members of the Ku Klux Klan who believed that the reason for this was that some members of the jury were African Americans. At a meeting held after the trial, Bennie Hays, the second-highest ranking official in the Klan in Alabama said: "If a black man can get away with killing a white man, we ought to be able to get away with killing a black man."

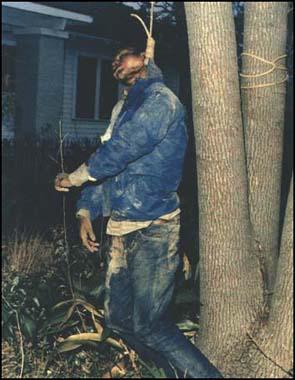

On Saturday 21st March, 1981, Bennie Hays's son, Henry Hays, and James Knowles, decided they would get revenge for the failure of the courts to convict the man for killing a policeman. They travelled around Mobile in their car until they found nineteen year old Donald walking home. After forcing him into the car Donald was taken into the next county where he was lynched.

A brief investigation took place and eventually the local police claimed that Donald had been murdered as a result of a disagreement over a drugs deal. Donald's mother, Beulah Mae Donald, who knew that her son was not involved with drugs, was determined to obtain justice. She contacted Jessie Jackson who came to Mobile and led a protest march about the failed police investigation.

Thomas Figures, the assistant United States attorney in Mobile, managed to persuade the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to look into the case. James Bodman was sent to Mobile and it did not take him long to persuade James Knowles to confess to the killing of Michael Donald.

In June 1983, Knowles was found guilty of violating Donald's civil rights and was sentenced to life imprisonment. Six months later, when Henry Hays was tried for murder, Knowles appeared as chief prosecution witness. Hays was found guilty and sentenced to death.

With the support of Morris Dees and Joseph J. Levin at the Southern Poverty Law Centre (SPLC), Beulah Mae Donald decided that she would use this case to try and destroy the Ku Klux Klan in Alabama. Her civil suit against the United Klans of America took place in February 1987. The all-white jury found the Klan responsible for the lynching of Michael Donald and ordered it to pay 7 million dollars. This resulted the Klan having to hand over all its assets including its national headquarters in Tuscaloosa.

After a long-drawn out legal struggle, Henry Hayes was executed on 6th June, 1997. It was the first time a white man had been executed for a crime against an African American since 1913.

Primary Sources

(1) The trial of James Knowles in June, 1983.

James Knowles: I've lost my family. I've got people after me now. Everything I said is true. I was acting as a Klansman when I done this. And I hope people learn from my mistake. I do hope you decide a judgement against me and everyone else involved. (Turning towards Beulah Mae Donald.) I can't bring your son back. God knows if I could trade places with him, I would. I can't. Whatever it takes - I have nothing. But I will have to do it. And if it takes me the rest of my life to pay it, any comfort it may bring, I hope it will.

Beulah Mae Donald: I do forgive you. From the day I found out who you all was, I asked God to take care of you all, and he has.

(2) Jesse KornBluth, A Mother's Justice, the Sunday Times (31st January, 1988)

From its new headquarters the SPLC undertook in 1984 its biggest anti-Klan project - using Mrs Donald's civil suit to dismantle Robert Shelton's branch of the Klan. Sheldon's men had been involved in the beating of Freedom Riders at the Birmingham bus station in 1961, in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham in 1963 and in the shooting of Viola Liuzzo near Selma in 1965.

(3) Frances Coleman, Mobile Register (1st June, 1997)

June 6 will be a sad day for Alabamians, whether their skins are white, black or brown. On that day -- the previous night, really, at 12:01 a.m. -- the state of Alabama will electrocute Henry Francis Hays for beating a black man to death 16 years ago, and then hanging his body from a tree.

The execution will rip the scab from the old, deep, nasty wound of racism, which in the 20th-century South alternately heals and festers. It will fester again this week as residents of the Heart of Dixie re-live the brutal death of 19-year-old Michael Donald.

It is a story of contrasts: The murderer, a white man, grew up in a home filled with hate and violence. The victim was reared by a loving mother and doting older siblings.

Henry Hays knew what he was about that night, when he and a friend set out to kill a black man. Michael Donald, on the other hand, was innocently walking up the street on a spring evening in Mobile to buy some cigarettes, when fate delivered him into the white men's hands.

Most vivid, though, is the contrast between fiction and reality. Michael Donald was murdered - beaten to death with a tree limb - not in the 1930s or '40s, even in the 1960s, but in 1981. Such things weren't supposed to happen almost 30 years after the Supreme Court declared "separate but equal'' unconstitutional, and nearly 20 years after the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Nor were they supposed to happen in Mobile, which in the 1960s had somehow managed to avoid the racial violence that erupted in Selma and Birmingham.

Black men kidnapped and beaten, their bodies strung up in a tree? That was something that happened on the dark back roads of Dallas County or over in the Mississippi Delta, not in Alabama's second-largest city.

But hate crimes aren't constrained by time, place or suppositions. The reality is that Michael Donald died just 16 years ago at the hands of two Ku Klux Klansmen. So what if his death came years after lynchings were supposed to have ceased, and in a place not known for such things?

Barely out of childhood, he was a tragic, latter-day victim of a time when it was safer to be white - when to be a black girl or woman was to invite sexual violence, and to be a black boy or man was to evoke daily disrespect, laced always with the potential for a fatal confrontation.

In the early hours of Friday morning, Henry Hays will pay for ending Michael Donald's life that day in 1981. He claims that he is innocent - death row residents generally say that - but the evidence shows otherwise. Yet Hays is also a victim, albeit in a much different way than Donald.

Reared by an abusive father who beat his sons mercilessly, he was steered into a life of brutality and hate - a life that one day included membership in the KKK. Hays learned little about love and less about tolerance.

Death penalty advocates tout execution as a deterrent to crime, and maybe it is in some respects. Henry Hays' death, though, will serve mostly as a sad commentary on a society that in 1997 - less than three years from the turn of the century - is having to electrocute a man for murdering another man, solely because of the color of his skin.