Winston Churchill: 1916-1926

On 5th December, 1916, Herbert Asquith, who had been prime minister for over eight years, was replaced by David Lloyd George. He brought in a War Cabinet that included only four other members: George Curzon, Alfred Milner, Andrew Bonar Law and Arthur Henderson. There was also the understanding that Arthur Balfour attended when foreign affairs were on the agenda. Lloyd George was therefore the only Liberal Party member in the War Cabinet.

The Daily Chronicle attacked the role that Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe, and the other Conservative Party supporting newspaper barons had removed a democratically elected government. It argued that the new government "will have to deal with the Press menace as well as the submarine menace; otherwise Ministries will be subject to tyranny and torture by daily attacks impugning their patriotism and earnestness to win the war." (1)

Lloyd George told Winston Churchill he wanted to include him in his new government but the Conservatives in his Cabinet had made it clear that they would only join on condition he was excluded. Churchill told a close friend that this was "the downfall of all my hopes and desires". A few days later Lloyd George sent George Riddell to see Churchill and told him that there was no intention to keep him out of office permanently. In return Churchill was expected not to criticise his new government. Churchill agreed and he was "politically quiescent" and his comments in the House of Commons were "constructive" during the first months of 1917. (2)

Minister of Munitions

In July 1917, Lloyd George told the Cabinet that he intended to appoint Churchill as his Minister of Munitions. Sir George Younger, Chairman of the Conservative Party, made a formal protest and the General Council of the Conservative National Union passed a resolution that Churchill's recall would be "an insult to the Army and Navy and an injury to the Country." George Curzon warned the Prime Minister: "It will be an appointment intensely unpopular with many of your chief colleagues... He is a potential danger in opposition. In the opinion of us he will as a member of the government be an active danger in our midst." (3)

Although back in the government Churchill was no longer part of the inner circle and as he was not a member of the War Cabinet he played no part in the crucial discussions on strategy. Even in his own field of responsibility he was often ignored. He tried very hard to overcome this situation but in August 1917, the Chief of the Imperial Staff William Robertson complained to Lloyd George about Churchill's interference in their work. Soon afterwards the First Lord of the Admiralty, Eric Geddes, objected to Churchill involving himself in questions such as destroyer design. (4)

Winston Churchill developed a close relationship with Brigadier General Charles Howard Foulkes, the General Officer Commanding the Special Brigade responsible for Chemical Warfare and Director of Gas Services. Foulkes worked closely with scientists working at the governmental laboratories at Porton Down near Salisbury. Churchill urged Foulkes to provide him with effective ways of using chemical weapons against the German Army. In November 1917 Churchill advocated the production of gas bombs to be dropped by aircraft. However, this idea was rejected "because it would involve the deaths of many French and Belgian civilians behind German lines and take too many scarce servicemen to operate and maintain the aircraft and bombs." Churchill accepted this advice but told the French Minister of Armaments, Louis Loucheur that "I am in favour of the greatest possible development of gas-warfare." (5)

According to Giles Milton, the author of Russian Roulette: How British Spies Thwarted Lenin's Global Plot (2013): "Trials at Porton suggested that the M Device was indeed a terrible new weapon. The active ingredient in the M Device was diphenylaminechloroarsine, a highly toxic chemical. A thermogenerator was used to convert this chemical into a dense smoke that would incapacitate any soldier unfortunate enough to inhale it... The symptoms were violent and deeply unpleasant. Uncontrollable vomiting, coughing up blood and instant and crippling fatigue were the most common features.... Victims who were not killed outright were struck down by lassitude and left depressed for long periods." (6)

M Device was an exploding shell that released a highly toxic gas derived from arsenic. Foulkes called it "the most effective chemical weapon ever devised". The scientist, John Haldane, later described the impact of this new weapon: "The pain in the head is described as like that caused when fresh water gets into the nose when bathing, but infinitely more severe... accompanied by the most appalling mental distress and misery." Foulkes argued that the strategy should be "the discharge of gas on a stupendous scale". This was to be followed by "a British attack, bypassing the trenches filled with suffocating and dying men". However, the war came to an end in November, 1918, before this strategy could be deployed. (7)

Government control of the munitions industry meant that the ministry was inevitably drawn into questions of industrial organisation and labour relations. He wanted to use the wartime concessions to permanently weaken the role of the trades unions and the position of the skilled worker. He could not understand that the "restrictive practices" were the only way skilled workers could protect their interests against the much more powerful employers. He eventually got into problems over wage differentials, his award of a rise to skilled workers, led to substantial unrest by unskilled workers who eventually secured a higher wage settlement. (8)

Secretary of State for War and Air

David Lloyd George did a deal with Arthur Bonar Law that the Conservative Party would not stand against Liberal Party members who had supported the coalition government and had voted for him in the Maurice Debate in the 1918 General Election. It was agreed that the Conservatives could then concentrate their efforts on taking on the Labour Party and the official Liberal Party that supported their former leader, H. H. Asquith. The secretary to the Cabinet, Maurice Hankey, commented: "My opinion is that the P.M. is assuming too much the role of a dictator and that he is heading for very serious trouble." (9)

Lloyd George ran a campaign that questioned the patriotism of Labour candidates. According to Duff Cooper, Lloyd George feared his tactics were not working and he asked the the main newspaper barons, Lord Northcliffe, Lord Rothermere and Lord Beaverbrook, for help in his propaganda campaign. (10) They arranged for candidates to be sent telegrams that demanded: "For the guidance of your constituency will you kindly state whether, if elected, you will support the following: (i) Punishment of the Kaiser (ii); Full payment for the war by Germany (iii); The expulsion from the British isles of all Enemy Aliens." (11)

Churchill urged very radical measures during the campaign. He urged the future government to consider a heavy tax on all war profits. "Why should anybody make a great fortune out of the war? Why everybody has been serving the country, profiteers and contractors and shipping speculators have gained fortunes of a gigantic character." His proposal was that the Government should "reclaim everything above, say, £10,000 (to let the small fry off)". This would enable Britain to substantially reduce its war debt "from the coffers of the war profiteers." (12)

Churchill demanded measures that some people claimed were socialistic. He called for the nationalisation of the railways, for the control of monopolies "in the general interest", and for taxation levied "in proportion to the ability to pay". However, he was a strong opponent of communism and was concerned about the political consequences of the Russian Revolution. In one speech he warned of the dangers of Bolshevism: "Civilisation is being completely extinguished over gigantic areas, while Bolsheviks hop and caper like troops of ferocious baboons amid the ruins of cities and the corpses of their victims." (13)

The General Election results was a landslide victory for David Lloyd George and the Coalition government: Conservative Party (382); Coalition Liberal (127), National Labour Coalition (4) and Coalition National Democrats (9) . The Labour Party won only 57 seats and lost most of its leaders including Arthur Henderson, Ramsay MacDonald, Philip Snowden, George Lansbury and Fred Jowett. The Liberal Party returned 36 seats and its leader H. H. Asquith was defeated at East Fife. (14)

Churchill was appalled by the success of the Labour Party who now became the official opposition. He did not see them as a legitimate political party as they were "innately pledged to the fundamental subversion of the existing social and economic civilisation and organised for that purpose alone." He told David Lloyd George: "The Labour Party... espouse and proclaim doctrines fundamentally subversive not only of the State and of the Empire, but of economic civilisation... I regard effectual resistance to Socialism - revolutionary or evolutionary - as a prime duty for those who wish to preserve the greatness of Britain and avert the establishment of a Socialist tyranny." (15)

On 10th January 1919, Winston Churchill was appointed Secretary of State for War and Air. Churchill wanted to keep conscription but in July, under financial pressure, he was forced to bring it to an end. He proposed a permanent peacetime army of 209,000 but this was rejected by his colleagues who insisted on returning to an army smaller than before 1914. Churchill also advocated large military cuts and suggested that there should be no new naval construction for many years. In August he suggested that expenditure on the Navy should be set at about two-thirds of the pre-war level. (16)

Hugh Trenchard, Chief of the Air Staff, proposed a large peacetime force of 154 squadrons and 100,000 men for the Royal Air Force. Churchill rejected this idea as he was only willing to spend £13 million out of an overall allocation of £75 million a year for the Army and Air Force. Although he kept the RAF short of money, Churchill insisted that its officers were drawn from the same exclusive background and followed the same traditions as the Royal Navy and Army. In July, 1919, he wrote a paper setting out the policy the RAF should adopt. Officer recruits should be chosen "by competitive examination, preferably from the public schools", because their most important characteristic should be "the discipline and bearing of an officer and a gentleman". (17)

After the war the ending of price controls, prices rose twice as fast during 1919 as they had done during the worst years of the war. That year 35 million working days were lost to strikes, and on average every day there were 100,000 workers on strike - this was six times the 1918 rate. There were stoppages in the coal mines, in the printing industry, among transport workers, and the cotton industry. There were also mutinies in the military and two separate police strikes in London and Liverpool. (18)

The government formed a Cabinet Strike Committee to deal with the crisis. Churchill was the key member of the committee and deployed 23,000 troops, with 30,000 more in reserve, to protect the railways and drive food lorries. General Douglas Haig, attended the first meeting and described Churchill as being the "most energetic and talked more than anyone". In August 1919 he sent in troops to Liverpool to defeat a local police strike. His main enemy was the miners and he argued that: "This is the time to beat them. There is bound to be a fight. The English propertied classes are not going to take it lying down." (19)

Winston Churchill thought Britain was on the verge of a revolution. He told the Supplies and Transport Committee of the Cabinet: "The country would have to face in the near future an organised attempt at seizing the reins of Government in some of the large cities, such as Glasgow, London and Liverpool... It was not unlikely that the next strike would commence with sabotage on an extensive scale." (20)

David Lloyd George agreed with Churchill and became convinced that Britain was on the verge of revolution that he was determined to suppress it. After inquiring about the number of troops available to him he asked Sir Hugh Trenchard, Chief of the Air Staff: "How many airman are available for the revolution? Trenchard replied that there were 20,000 mechanics and 2,000 pilots, but only a hundred machines which could be kept going in the air... The pilots had no weapons for ground fighting. The PM presumed they could use machine guns and drop bombs." (21)

Churchill remained convinced that the military should be able to use chemical weapons against civilians in order to protect the British Empire. In April 1919, Churchill asked for permission to use mustard gas (a gas that causes severe blistering and kills about ten per cent of those affected) in Mesopotamia: "I do not understand this squeamishness about the use of gas... I am strongly in favour of using poisoned gases against uncivilised tribes. The moral effect should be so good that the loss of life should be reduced to a minimum... Gases can be used which cause great inconvenience and would leave a lively terror." (22)

Churchill also used chemical weapons in May 1919 to subdue rebels in Afghanistan. When the India Office objected to this policy he replied: "The objections of the India Office to the use of gas against natives are unreasonable. Gas is a more merciful weapon than high explosive shell and compels an enemy to accept a decision with less loss of life than any other agency of war. The moral effect is also very great. There can be no conceivable reason why it should not be resorted to." (23)

Churchill held a very low opinion of the Arabs and felt they deserved to lose their home to more advanced Europeans. He described the Arabs as acting like a "dog in a manger". He told the Peel Commission: "I do not agree that the dog in a manger has the final right to the manger, even though he may have lain there for a very long time. I do not admit that right. I do not admit, for instance, that a great wrong has been done to the Red Indians of America, or the black people of Australia. I do not admit that a wrong has been done to these people by the fact that a stronger race, a higher grade race, or at any rate, a more worldly-wise race, to put it that way, has come in and taken their place." (24)

However, his main enemy during this period was communism. He feared that the revolution would spread from Russia to western Europe. All the members of the government opposed Bolshevism but no one hated it like he did. He told the House of Commons that "Bolshevism is not a policy; it is a disease. It is not a creed; it is a pestilence." (25) He described the Bolsheviks as "swarms of typhus-bearing vermin". (26) In article in The Evening News he claimed that the Bolsheviks had created "a poisoned Russia, an infected Russia, a plague bearing Russia." (27)

Churchill blamed Jews for the Russian Revolution. He told Lord George Curzon, the Foreign Secretary, that in his opinion that the Bolsheviks had created a "tyrannical government of these Jew Commissars". In a letter to Frederick Smith he described them as "these Semitic conspirators" and "Semitic internationalists". In one speech he called the Russian government "a world wide communistic state under Jewish domination." At a public meeting in Sunderland he spoke of "the international Soviet of the Russian and Polish Jew." (28)

In an article in the Illustrated Sunday Herald he argued: "The part played in the creation of Bolshevism and in the actual bringing about of the Russian Revolution by these international and for the most part atheistic Jews ... is certainly a very great one; it probably outweighs all others. With the notable exception of Lenin, the majority of the leading figures are Jews. Moreover, the principal inspiration and driving power comes from Jewish leaders ... The same evil prominence was obtained by Jews in (Hungary and Germany, especially Bavaria)." (29)

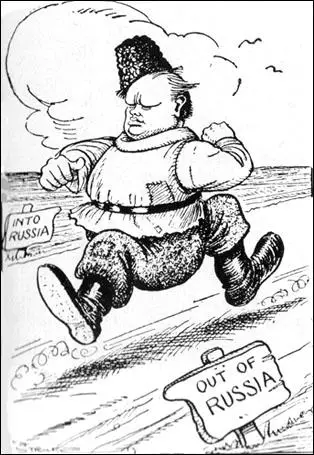

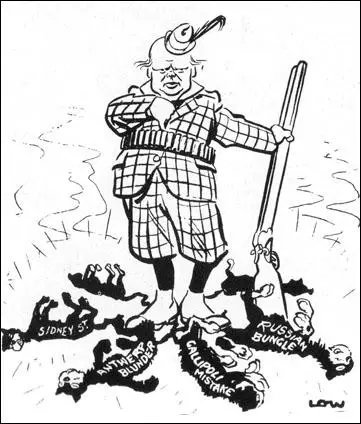

Churchill had supported the sending of British troops to help the White Army in the Russian Civil War, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel John Ward. However, it had not been a success Ward later told one of his officers, Brian Horrocks: "I believe we shall rue this business for many years. It is always unwise to intervene in the domestic affairs of any country. In my opinion the Reds are bound to win and our present policy will cause bitterness between us for a long time to come." Horrocks agreed: "How right he was: there are many people today who trace the present international impasse back to that fatal year of 1919." (30)

Churchill argued that the British had not sent enough troops. He argued in a Cabinet meeting that Britain should intervene "thoroughly, with large forces, abundantly supplied with mechanical appliances". He also suggested a campaign to recruit a volunteer army to fight in Russia. David Lloyd George admitted that the Cabinet was united in its hostility to the Bolsheviks but they did have support in Russia. He added that Britain had no right to interfere in their internal affairs and anyway lacked the means to do so. (31)

Winston Churchill now took the controversial decision to use the stockpiles of M Device against the Red Army. He was supported in this by Sir Keith Price, the head of the chemical warfare, at Porton Down. He declared it to be the "right medicine for the Bolshevist" and the terrain would enable it to "drift along very nicely". Price agreed with Churchill that the use of chemical weapons would lead to a rapid collapse of the Bolshevik government in Russia: "I believe if you got home only once with the Gas you would find no more Bolshies this side of Vologda." (32)

In the greatest secrecy, 50,000 M Devices were shipped to Archangel, along with the weaponry required to fire them. Winston Churchill sent a message to Major-General William Ironside: "Fullest use is now to be made of gas shell with your forces, or supplied by us to White Russian forces." He told Ironside that this "thermogenerator of arsenical dust that would penetrate all known types of protective mask". Churchill added that he would very much like the "Bolsheviks" to have it. Churchill also arranged for 10,000 respirators for the British troops and twenty-five specialist gas officers to use the equipment. (33)

Some one leaked this information and Winston Churchill was forced to answer questions on the subject in the House of Commons on 29th May 1919. Churchill insisted that it was the Red Army who was using chemical warfare: "I do not understand why, if they use poison gas, they should object to having it used against them. It is a very right and proper thing to employ poison gas against them." His statement was untrue. There is no evidence of Bolshevik forces using gas against British troops and it was Churchill himself who had authorised its initial use some six weeks earlier. (34)

On 27th August, 1919, British Airco DH.9 bombers dropped these gas bombs on the Russian village of Emtsa. According to one source: "Bolsheviks soldiers fled as the green gas spread. Those who could not escape, vomited blood before losing consciousness." Other villages targeted included Chunova, Vikhtova, Pocha, Chorga, Tavoigor and Zapolki. During this period 506 gas bombs were dropped on the Russians. Lieutenant Donald Grantham interviewed Bolshevik prisoners about these attacks. One man named Boctroff said the soldiers "did not know what the cloud was and ran into it and some were overpowered in the cloud and died there; the others staggered about for a short time and then fell down and died". Boctroff claimed that twenty-five of his comrades had been killed during the attack. Boctroff was able to avoid the main "gas cloud" but he was very ill for 24 hours and suffered from "giddiness in head, running from ears, bled from nose and cough with blood, eyes watered and difficulty in breathing." (35)

Major-General William Ironside told David Lloyd George that he was convinced that even after these gas attacks his troops would not be able to advance very far. He also warned that the White Army had experienced a series of mutinies (there were some in the British forces too). Lloyd George agreed that Ironside should withdraw his troops. This was completed by October. The remaining chemical weapons were considered to be too dangerous to be sent back to Britain and therefore it was decided to dump them into the White Sea. (36)

Winston Churchill created great controversy by the creation of Iraq. According to Boris Johnson: "He (Churchill) was the man who decided that there should be such a thing as the state of Iraq, if you wanted to blame anyone for the current implosion, then of course you might point the finger at George W. Bush and Tony Blair and Saddam Hussein - but if you wanted to grasp the essence of the problem of that wretched state, you would have to look at the role of Winston Churchill." (37)

An uprising of more than 100,000 armed tribesmen took place in 1920. It was estimated that around 25,000 British and 80,000 Indian troops would be needed to control the country. However, he argued that if Britain relied on air power, you could cut these numbers to 4,000 (British) and 10,000 (Indian). The government was convinced by this argument and it was decided to send the recently formed Royal Air Force to Iraq. Over the next few months the RAF dropped 97 tons of bombs killing 9,000 Iraqis. This failed to end the resistance and Arab and Kurdish uprisings continued to pose a threat to British rule. Churchill decided to use chemical weapons on the rebels. He told Sir Hugh Trenchard, Chief of the Air Staff, that "mustard gas could be used "without inflicting grave injury" on its victims. (38)

At a meeting on 14th October, 1922, two younger members of the government, Stanley Baldwin and Leo Amery, urged the Conservative Party to remove Lloyd George from power. Andrew Bonar Law disagreed as he believed that he should remain loyal to the Prime Minister. In the next few days Bonar Law was visited by a series of influential Tories - all of whom pleaded with him to break with Lloyd George. This message was reinforced by the result of the Newport by-election where the independent Conservative won with a majority of 2,000, the coalition Conservative came in a bad third. (39)

Another meeting took place on 18th October. Austen Chamberlain and Arthur Balfour both defended the coalition. However, it was a passionate speech by Baldwin: "The Prime Minister was described this morning in The Times, in the words of a distinguished aristocrat, as a live wire. He was described to me and others in more stately language by the Lord Chancellor as a dynamic force. I accept those words. He is a dynamic force and it is from that very fact that our troubles, in our opinion, arise. A dynamic force is a terrible thing. It may crush you but it is not necessarily right." The motion to withdraw from the coalition was carried by 187 votes to 87. (40)

Winston Churchill, a candidate for the David Lloyd George Liberals, was taken ill suffering from appendicitis during the early stages of the 1922 General Election. He was therefore unable to campaign in Dundee to just before the vote took place. The statement issued that explained his decision did not help his cause as it emphasized his wealthy background: "Mr Churchill's medical advisors, Lord Dawson, Sir Crisp English and Dr Hartigan, have consented to his fixing provisionally Saturday, November 11th, as the date when he can address a public meeting in Dundee." (41)

The Conservative Party did not put up a candidate against Churchill. His main rival was E. D. Morel, the Labour Party candidate. Morel was the founder of the Union of Democratic Control (UDC), the main organisation that opposed the First World War. Another opponent was William Gallacher, a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, who had also been an anti-war activist. From his Dorset Square nursing home Churchill attacked the policies of Morel and Gallacher: "A predatory and confiscatory programme fatal to the reviving prosperity of the country, inspired by class jealously and the doctrines of envy, hatred and malice, is appropriately championed in Dundee by two candidates both of whom had to be shut up during the late war in order to prevent them further hampering the national defence." (42)

Churchill launched a bitter campaign against Morel and Gallacher and accused them of belonging to a "band of degenerate international intellectuals". He added: "Mr Gallacher is only Mr Morel with the courage of his convictions, and Trotsky is only Mr Gallacher with the power to murder those whom he cannot convince." In this working-class constituency Churchill's obvious wealth and English upper-class attitudes, worked against him. On 13th November 1922 Churchill tried to make a public speech but he was shouted down and had to abandon the meeting. (43) During the campaign Benito Mussolini took power in Italy and Edwin Scrymgeour, observed that it would not surprise him in the event of civil war in Britain "if Mr Churchill were at the head of the Fascisti party". (44)

Morel defeated Churchill by 30,292 votes to 20,466. The Conservative Party achieved 344 seats and formed the next government. The Labour Party, who promised to nationalise the mines and railways, a massive house building programme and to revise the peace treaties, went from 57 to 142 seats. In third place came the Liberals. They accounted for nearly a third of the vote but were badly split - Lloyd George's faction won forty-seven seats, those supporting H. H. Asquith, forty and uncommitted members twenty-nine. (45)

Winston Churchill rejoins the Conservative Party

General Edward Louis Spears, offered to resign as coalition Liberal MP for Loughborough in order that Churchill could return to the House of Commons. Churchill refused as he now realised that the Liberal Party would never again take power. If he wanted to become a minister again he would have to rejoin the Conservative Party. Churchill left England at the end of November 1922 and spent the next six months living near Cannes working on his war memoirs. The first volume was published on 10th August, 1923. In its review the New Statesman commented: "He (Churchill) has written a book which is remarkably egotistical, but which is honest and which will certainly long survive him." (46)

In the second volume of World Crisis: 1911-1918 (1923) Churchill attempted to explain his actions during the Dardanelles Campaign. He sent a copy to Stanley Baldwin who replied a few days later that, "If I could write as you do, I should never bother about making speeches!" The book contained many of the documents that the Dardanelles Commission had refused to publish." Leo Amery, the First Lord of the Admiralty, wrote of his admiration "for the skill of the narrative itself" and of his sympathy for Churchill "in your struggle against the impregnable wall of pedantry or in the appalling morasses of irresolution." (47)

It was not until May, 1923, that he made it clear he intended to return to politics. In a speech that he made at the Aldwych Club he made an attack on Asquith who had refused to work with the Conservatives. He said it was the responsibility of politicians to do everything possible to prevent the growth of the Labour Party. He wanted to join forces with any party with "the clear purpose of rallying the greatest number of persons of all classes... to the defence of the existing constitution" so as to resist "the ceaseless advance and... victorious enforcement of the levelling and withering doctrines of socialism". (48)

Churchill also argued that Conservative politicians would never undo the achievements of the Liberal Government of which he had been a member. In private Churchill put it rather differently. He told senior figures in the Tory party it was only because of the political situation that forced him to be a Liberal minister for most of the last seventeen years. He told Sir Robert Horne that "force of circumstances has compelled me to serve with another party, but my views have never changed, and I should be glad to give effect to them by rejoining the Conservatives." (49)

On 17th May, 1923, Andrew Bonar Law was told he was suffering from cancer of the throat, and gave him six months to live. Five days later he resigned and was replaced by Stanley Baldwin. It was a difficult time for the government and it was faced with growing economic problems. This included a high-level of unemployment. Baldwin believed that protectionist tariffs would revive industry and employment. However, Bonar Law had pledged in 1922 that there would be no changes in tariffs in the present parliament. Baldwin came to the conclusion that he needed a General Election to unite his party behind this new policy. On 12th November, Baldwin asked the king to dissolve parliament. (50)

During the election campaign, Baldwin made it clear that he intended to impose tariffs on some imported goods: "What we propose to do for the assistance of employment in industry, if the nation approves, is to impose duties on imported manufactured goods, with the following objects: (i) to raise revenue by methods less unfair to our own home production which at present bears the whole burden of local and national taxation, including the cost of relieving unemployment; (ii) to give special assistance to industries which are suffering under unfair foreign competition; (iii) to utilise these duties in order to negotiate for a reduction of foreign tariffs in those directions which would most benefit our export trade; (iv) to give substantial preference to the Empire on the whole range of our duties with a view to promoting the continued extension of the principle of mutual preference which has already done so much for the expansion of our trade, and the development, in co-operation with the other Governments of the Empire, of the boundless resources of our common heritage." (51)

Baldwin's strategy made it impossible for Churchill to become a member of the Conservative Party. Having left the Conservatives on the issue of Free Trade twenty years earlier, he could hardly rejoin them on the basis of protection now. Churchill agreed to stand as the Liberal Party candidate for West Leicester. He appealed for the unity of both wings of the party led by David Lloyd George and H. H. Asquith. In a speech made during the campaign he stated that "Liberalism" was the only "sure, sober, safe middle course of lucid intelligence and high principle". (52)

Churchill's main opponent was Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, the Labour Party candidate, who had played a major role in the women's suffrage campaign and was one of the main financial supporters of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). Churchill was heckled at public meetings with shouts of "What about the Dardanelles?" On one occasion he replied: "What do you know about the Dardanelles? The Dardanelles might have saved millions of lives. Don't imagine I am running away from the Dardanelles. I glory in it." (53)

The 1923 General Election was held on 6th December, a week after Churchill's forty-ninth birthday. Pethick-Lawrence had an easy victory and beat Churchill by 13,634 to 9,236 votes. The election was won by the Conservatives with 258 seats. The Labour Party was in second place with 191 seats. Asquith announced that the Liberal Party would not keep the Tories in office. If a Labour Government were ever to be tried in Britain, he declared, "it could hardly be tried under safer conditions". The Daily Mail warned about the dangers of a Labour government and the Daily Herald commented on the "Rothermere press as a frantic attempt to induce Mr Asquith to combine with the Tories to prevent a Labour Government assuming office". (54) John R. Clynes, the former leader of the Labour Party, argued: "Our enemies are not afraid we shall fail in relation to them. They are afraid that we shall succeed." (55)

On 22nd January, 1924, Stanley Baldwin resigned. At midday, the 57 year-old, Ramsay MacDonald went to Buckingham Palace to be appointed prime minister. He later recalled how George V complained about the singing of the Red Flag and the La Marseilles, at the Labour Party meeting in the Albert Hall a few days before. MacDonald apologized but claimed that there would have been a riot if he had tried to stop it. (56)

Robert Smillie, the Labour MP for Morpeth, believed that MacDonald had made a serious mistake in forming a government. "At last we had a Labour Government! I have to tell you that I did not share in that jubilation. In fact, had I had a voice in the matter which, as a mere back-bencher I did not, I would have strongly advised MacDonald not to touch the seals of office with the proverbial barge pole. Indeed, I was very doubtful indeed about the wisdom of forming a Government. Given the arithmetic of the situation, we could not possibly embark on a proper Socialist programme." (57)

Winston Churchill believed that the Liberal Party would never be strong enough to form another government and that he would have to rejoin the Conservative Party as the best way of becoming a minister again. However, he was hated by most Tory politicians who remembered the vicious attacks on the party after he joined the Liberals. Churchill convinced himself that he had always been a Conservative at heart and only an unfortunate set of circumstances had forced him to join the Liberal Party. (58)

On 22nd February, 1924, Churchill discovered there was to be a by-election in the strongly Conservative seat of Westminster Abbey. He approached the Conservative Party and offered to become its candidate. This was rejected by Stanley Baldwin and was told to wait for another opportunity. Austen Chamberlain wrote to Churchill's friend, Frederick Smith, Lord Birkenhead: "We want to get him (Churchill) and his friends over, and although we cannot give him the Abbey seat, Baldwin will undertake to find him a good seat later on when he will have been able to develop naturally his new line and make his entry into our ranks much easier than it would be today. Our only fear is lest Winston should try and rush the fence." (59)

Churchill explained: "I found myself free a few months later to champion the anti-Socialist cause in the Westminster by-election, and so regained for a time at least the goodwill of all those strong Conservative elements, some of whose deepest feelings I share and can at critical moments express, although they have never liked or trusted me. But for my erroneous judgment in the General Election of 1923 I should have never have regained contact with the great party into which I was born and from which I had been severed by so many years of bitter quarrel. (60)

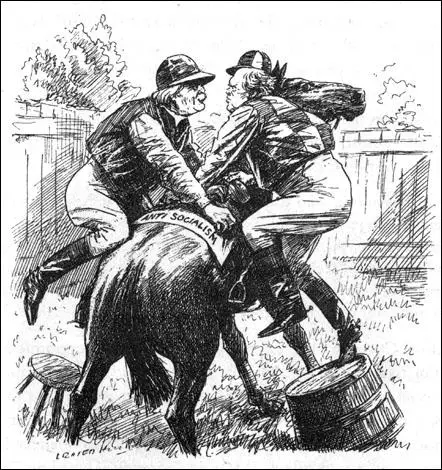

Winston Churchill ignored the advice of Austen Chamberlain and stood as an anti-socialist candidate, because the Labour Government was a challenge to "our existing economic and social civilisation". Otho Nicholson the Conservative candidate won by 43 votes but Churchill's intervention allowed Fenner Brockway, the Labour candidate to finish a close third. Soon afterwards he was given the safe Conservative seat of Epping. (61)

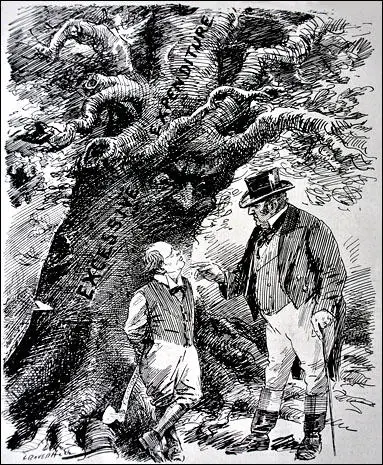

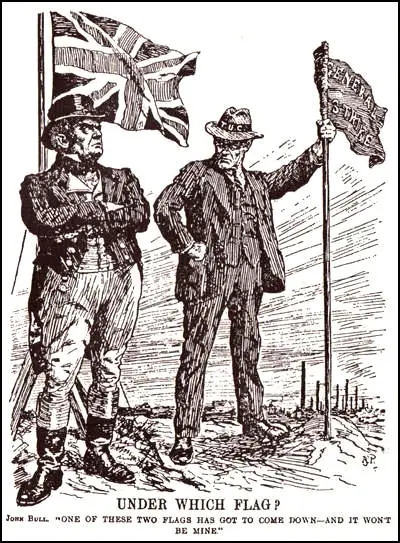

Winston Churchill: "No, it isn't. I thought of it first."

Leonard Raven-Hill, The Fight for the Favourite (4th June, 1924)

During the 1924 General Election campaign he argued "I represent uncompromising opposition to the subversive movement of Socialism, and I equally oppose those who are willing to make... compromising bargains with the Socialists." (62) In another speech he insisted that "I am in favour of developing trade within the Empire, but I am not in favour of risking our money on Russia and other foreigners." (63)

The Daily Mail published the Zinoviev Letter on 25th October 1924, just four days before the 1924 General Election. Under the headline "Civil War Plot by Socialists Masters" it argued: "Moscow issues orders to the British Communists... the British Communists in turn give orders to the Socialist Government, which it tamely and humbly obeys... Now we can see why Mr MacDonald has done obeisance throughout the campaign to the Red Flag with its associations of murder and crime. He is a stalking horse for the Reds as Kerensky was... Everything is to be made ready for a great outbreak of the abominable class war which is civil war of the most savage kind." (64)

Bob Stewart claimed that the letter included several mistakes that made it clear it was a forgery. This included saying that Grigory Zinoviev was not the President of the Presidium of the Communist International. It also described the organisation as the "Third Communist International" whereas it was always called "Third International". Stewart argued that these "were such infantile mistakes that even a cursory examination would have shown the document to be a blatant forgery." (65)

The rest of the Tory owned newspapers ran the story of what became known as the Zinoviev Letter over the next few days and it was no surprise when the election was a disaster for the Labour Party. The Conservatives won 412 seats and formed the next government. Lord Beaverbrook, the owner of the Daily Express and Evening Standard, told Lord Rothermere, the owner of The Daily Mail and The Times, that the "Red Letter" campaign had won the election for the Conservatives. Rothermere replied that it was probably worth a hundred seats. (66)

Chancellor of the Exchequer

Churchill defeated the Liberal candidate, Gilbert Granville Sharp, by nearly 10,000 votes. Austen Chamberlain advised Stanley Baldwin to put Churchill in the Cabinet: "If you leave him out, he will be leading a Tory rump in six months' time." (67) Thomas Jones, one of Baldwin's leading advisers, commented: "I would certainly have him inside, not out" and suggested sending him to the Board of Trade or the Colonial Office. Baldwin eventually decided to offer him the post of Chancellor of the Exchequer. Churchill replied: "This fulfils my ambition. I still have my father's robes as Chancellor. I shall be proud to serve you in this splendid office." (68)

Churchill had no experience of financial or economic matters when he went to the Treasury in November 1924. He made it clear to Sir Richard Hopkins, the chairman of the Board of Inland Revenue that he had no intention of increasing taxes on the rich: "As the tide of taxation recedes it leaves the millionaires stranded on the peaks of taxation to which they have been carried by the flood... Just as we have seen the millionaire left close to the high water mark and the ordinary Super Tax payer draw cheerfully away from him, so in their turn the whole class of Super Tax payer will be left behind on the beach as the great mass of the Income Tax payers subside into the refreshing waters of the sea." (69)

Churchill's first major decision concerned the Gold Standard. Britain had left the gold standard in 1914 as a wartime measure, but it was always assumed by the City of London financial institutions that once the war was over Britain would return to the mechanism that had seemed so successful before the war in providing stability, low interest rates and a steady expansion in world trade. However, at the end of the First World War, the British economy was in turmoil. After a short-term boom in 1919 gross domestic fell by six per cent and unemployment rose rapidly to 23 per cent. (70)

Montagu Norman, the governor of the Bank of England and Otto Niemeyer, a senior figure at the Treasury, were both strong supporters of a return to the gold standard. Niemeyer said to dodge the issue now would be to show that Britain had never really "meant business" about the Gold Standard and that "our nerve had failed when the stage was set." Norman added that in the opinion "of educated and reasonable men" there was no alternative to a return to Gold. The Chancellor would no doubt be attacked whatever he did but "in the former case (Gold) he will be abused by the ignorant, the gamblers and the antiquated industrialists". (71)

Churchill was not convinced as he was aware of the alternative ideas of John Maynard Keynes. He told Niemeyer: "The Treasury has never, it seems to me, faced the profound significance of what Mr Keynes calls `the paradox of unemployment amidst dearth'. The Governor shows himself perfectly happy in the spectacle of Britain possessing the finest credit in the world simultaneously with a million and a quarter unemployed. Obviously if these million and a quarter were usefully and economically employed, they would produce at least £100 a year a head, instead of costing up at least £50 a head in doles." (72)

Churchill also sought the advice of Philip Snowden, who had served as Chancellor of the Exchequer, in the previous Labour government. Snowden said he was in favour of a return to the Gold Standard at the earliest possible moment. On 17th March, 1925, Churchill gave a dinner that was attended by supporters and opponents of returning to the Gold Standard. He admitted that Keynes provided the better arguments but as a matter of practical politics he had no alternative but to go back to Gold. (73).

Roy Jenkins has argued that the return to the Gold Standard was the gravest mistake of the Baldwin government: "Churchill was deliberately a very attention-attracting Chancellor. He wanted his first budget to make a great splash, which it did, and a considerable contribution to the spray was made by the announcement of the return to Gold. Reluctant convert although he had been, he therefore deserved the responsibility and, if it be so judged, a considerable part of the blame." (74)

Other measures in his first budget included a move towards Imperial Preference and some modest tariffs to help members of the British Empire: sugar (West Indies), tobacco (Kenya and Rhodesia), wines (South Africa and Australia) and dried fruits (Middle East). This marked his move away from the doctrinaire liberalism of his earlier years. He also announced a reduction of income tax by sixpence to four shillings in the pound. "He made out to be beneficial to the worse off as well as the prosperous, but which pleased the latter most." The wealthy were also pleased by a reduction in super tax. (75)

Churchill was attempting to deal with the social problems of the country without recourse to Socialism. Philip Snowden, the former Labour chancellor of the exchequer, called it "the worst rich man's budget ever presented". (76) Treasury officials, including the Permanent Secretary Sir Warren Fisher, thought that it was a very bad budget as it gave too much away and so would cause problems for the next few years. Fisher told Neville Chamberlain that Churchill was "a lunatic... an irresponsible child, not a grown man" and complained that all the senior officials in the Treasury had lost heart - "they never know where they are or what hare W.C. will start". (77)

As a result of returning to the Gold Standard the country took little part in the world boom from 1925 to 1929 and its share of world markets continued to fall. The balance of payments surplus recorded in 1924 disappeared and overpriced British exports slumped. The overvalued pound meant that costs had to be reduced in an unavailing attempt to keep exports competitive. This meant cuts in labour costs at a time when real wages were already below 1914 levels. Attempts to impose further wage reductions inevitably led to industrial disputes, lock-outs and strikes. It has been estimated that returning to the Gold Standard made as many as 700,000 people unemployed. (78)

Despite the problem of low Government revenues Churchill was determined not to increase personal taxes. In 1925 the majority of people did not pay income tax - only 2½ million people were liable and just 90,000 paid super-tax. The standard rate of income tax was reduced from four shillings and sixpence to four shillings in the pound. The super-tax was reduced by £10 million, which was substantial in relation to the total yield of the tax at £60 million: "This was of substantial benefit to the rich, not only as individual taxpayers but also in the capacity of many of them as shareholders, for income tax was then the principal form of company taxation." (79)

In a letter to James Gascoyne-Cecil, 4th Marquess of Salisbury, the leader of the House of Lords, he argued that "the rich, whether idle or not, are already taxed in this country to the very highest point compatible with the accumulation of capital for further production." (80) In a second letter he stated that cutting taxes was a "class measure" that was designed to help the comfortably off and the rich." (81)

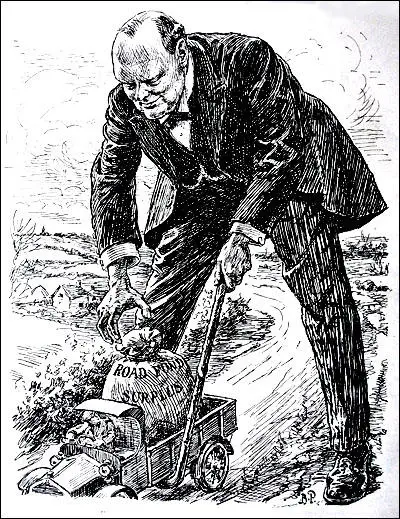

Churchill was warned that he needed to find ways of balancing the budget. He was unwilling to increase income-tax and super-tax and so he decided to raid the "Road Fund", for which revenue had risen to the substantial sum of £21.5 million. It was assumed that this money would be used for building new roads. Churchill disagreed and took £7 million from the Road Fund that year. When the Automobile Association complained about this Churchill wrote "such contentions are absurd, and constitute at once an outrage upon the sovereignty of Parliament and upon commonsense." (82)

Churchill's social conservatism was also apparent during discussions within the Government over changes to unemployment insurance. The scheme that the Liberal government had introduced in 1911 had collapsed after the war because of large-scale structural unemployment, particularly among trades that were not covered by the scheme. A benefit (the dole) was first introduced for unemployed ex-servicemen, later extended to others and then made subject to a means test in 1922. Churchill thought that far too many people were drawing the "dole". (83)

Winston Churchill spoke in the House of Commons of the "growing up of a habit of qualifying for unemployment relief" and the need for an enquiry. (84) Three weeks later he told Thomas Jones, the Deputy Secretary of the Cabinet, that "there should be an immediate stiffening of the administration, and the position should be made much more difficult for young unmarried men living with relatives, wives with husbands at work, aliens, etc." (85)

Winston Churchill: "I will not tell a lie. With my little hatchet

I have failed to make much impression. But I will keep trying. "

Leonard Raven-Hill, Last Orders (5th May, 1926)

Churchill wrote to Arthur Steel-Maitland, the Minister of Labour, to explain his ideas. He suggested that when the legislation to pay for the dole expired in 1926, rather than reduce the benefit, as most of his colleagues wanted to do, they should abolish it altogether. Churchill said: "It is profoundly injurious to the state that this system should continue; it is demoralising to the whole working class population... it is charitable relief; and charitable relief should never be enjoyed as a right." Churchill told Steel-Maitland that the huge number of unemployed families would have to depend on private charity once their insurance benefits were exhausted. The Government might make some donations to charities but money would only be given to "deserving cases" and that "by proceeding on the present lines we are rotting the youth of the country and rupturing the mainsprings of its energies". (86)

Churchill attempted to get his ideas supported by Stanley Baldwin, the prime minister: "I am thinking less about saving the exchequer than about saving the moral fibre of our working classes." (87) Churchill did not get his way. The other members of the Government, regardless of any possible moral consequences, could not face the political impact of ending the ‘dole' at a time when over a million people were out of work. "Nevertheless he was able to achieve the objective he referred to as less important – reducing the cost to the Exchequer by cutting the level of benefits for the unemployed. In 1926 the Treasury's contribution to the health and unemployment schemes was reduced by eleven per cent (to save £2.5 million on the health scheme) and a Royal Commission recommendation to extend the schemes was ignored. In 1927 the unemployment benefit for single men was reduced by a shilling a week." (88)

Winston Churchill was successful with persuading his cabinet colleagues that the test that the unemployed had to pass was stiffened: they now had to prove that they were "genuinely seeking work" even if there were no jobs available. The Government was able to increase, as a matter of deliberate policy, the rejection rate from three per cent in 1924 to over eighteen per cent by 1927. In November 1925 he was also able to convince his colleagues that "to the utmost extent possible Government unemployment relief schemes should be closed down" in order to save money. (89)

The General Strike

Churchill was a strong supporter of introducing legislation to weaken the labour movement. He was especially keen to force trade union members to voluntarily 'contract in' to pay the political levy to the Labour Party. The right-wing Tory MP, Frederick A. Macquisten, introduced his own private members bill on the subject. Macquisten argued that trade unions were guilty of imposing taxes on its members. "What I am proposing now is to relieve the working man of this liability to be taxed." (90)

In the House of Commons, Churchill supported the measure but Stanley Baldwin rejected the idea on moral grounds as the the trade unions were weak at this time because of increasing unemployment. "We find ourselves, after these two years in power, in possession of perhaps the greatest majority our party has ever had, and with the general assent of the country. Now how did we get there? It was not by promising to bring this Bill in; it was because, rightly or wrongly, we succeeding in creating an impression throughout the country that we stood for stable Government and for peace in the country between all classes of the community." He appealed to his own Party's sense of British fair-play, they should not, he said, push home their advantage at a "time like this". Baldwin claimed that "stability at home and abroad was what was needed" and he was unwilling to "fire the first shot". He concluded with an appeal from the Book of Common Prayer: "Give peace in our time, O Lord." (91)

On 30th June 1925 the mine-owners announced that they intended to reduce the miner's wages. Will Paynter later commented: "The coal owners gave notice of their intention to end the wage agreement then operating, bad though it was, and proposed further wage reductions, the abolition of the minimum wage principle, shorter hours and a reversion to district agreements from the then existing national agreements. This was, without question, a monstrous package attack, and was seen as a further attempt to lower the position not only of miners but of all industrial workers." (92)

On 23rd July, 1925, Ernest Bevin, the general secretary of the Transport & General Workers Union (TGWU), moved a resolution at a conference of transport workers pledging full support to the miners and full co-operation with the General Council in carrying out any measures they might decide to take. A few days later the railway unions also pledged their support and set up a joint committee with the transport workers to prepare for the embargo on the movement of coal which the General Council had ordered in the event of a lock-out." (93) It has been claimed that the railwaymen believed "that a successful attack on the miners would be followed by another on them." (94)

In an attempt to avoid a General Strike, the prime minister, Stanley Baldwin, invited the leaders of the miners and the mine owners to Downing Street on 29th July. The miners kept firm on what became their slogan: "Not a minute on the day, not a penny off the pay". Herbert Smith, the president of the Miners' Federation of Great Britain, told Baldwin: "We have now to give". Baldwin insisted there would be no subsidy: "All the workers of this country have got to take reductions in wages to help put industry on its feet." (95)

The following day the General Council of the Trade Union Congress triggered a national embargo on coal movements. On 31st July, the government capitulated. It announced an inquiry into the scope and methods of reorganization of the industry, and Baldwin offered a subsidy that would meet the difference between the owners' and the miners' positions on pay until the new Commission reported. The subsidy would end on 1st May 1926. Until then, the lockout notices and the strike were suspended. This event became known as Red Friday because it was seen as a victory for working class solidarity. (96)

Herbert Smith pointed out that the real battle was to come: "We have no need to glorify about a victory. It is only an armistice, and it will depend largely how we stand between now and May 1st next year as an organisation in respect of unity as to what will be the ultimate results. All I can say is, that it is one of the finest things ever done by an organisation." (97)

Red Friday was a great success for Smith and Arthur J. Cook, general secretary of the MFGB. However, Margaret Morris has argued that they had a difficult relationship: "Smith was temperamentally and politically the antithesis of Cook. Where Cook was emotional and voluble, Smith was dour and short of words. He was an old-style union leader, used to dominating the miners in Yorkshire... Relations between Smith and Cook were not always harmonious; neither of them really trusted the other's judgement, but each could respect that the other was dedicated to serving the miners. Neither of them was a very good negotiator: Cook was too excitable, and Smith perhaps a little too defensive in his tactics." (98)

The General Strike began on 3rd May, 1926. Arthur Pugh, the chairman of the Trade Union Congress, was put in charge of the strike. The Trade Union Congress adopted the following plan of action. To begin with they would bring out workers in the key industries - railwaymen, transport workers, dockers, printers, builders, iron and steel workers - a total of 3 million men (a fifth of the adult male population). Only later would other trade unionists, like the engineers and shipyard workers, be called out on strike. Ernest Bevin, the general secretary of the Transport & General Workers Union (TGWU), was placed in charge of organising the strike. (99)

The TUC decided to publish its own newspaper, The British Worker, during the strike. Some trade unionists had doubts about the wisdom of not allowing the printing of newspapers. Workers on the Manchester Guardian sent a plea to the TUC asking that all "sane" newspapers be allowed to be printed. However, the TUC thought it would be impossible to discriminate along such lines. Permission to publish was sought by George Lansbury for Lansbury's Labour Weekly and H. N. Brailsford for the New Leader. The TUC owned Daily Herald also applied for permission to publish. Although all these papers could be relied upon to support the trade union case, permission was refused. (100)

The government reacted by publishing The British Gazette. Baldwin gave permission to Winston Churchill to take control of this venture and his first act was commandeer the offices and presses of The Morning Post, a right-wing newspaper. The company's workers refused to cooperate and non-union staff had to be employed. Baldwin told a friend that he gave Churchill the job because "it will keep him busy, stop him doing worse things". He added he feared that Churchill would turn his supporters "into an army of Bolsheviks". (101)

Churchill, along with Frederick Smith, Lord Birkenhead, were members of the government who saw the strike as "an enemy to be destroyed." Lord Beaverbrook described him as being full of the "old Gallipoli spirit" and in "one of his fits of vainglory and excessive excitement". Thomas Jones attempted to develop a plan that would bring the dispute to an end. Churchill was furious and said that the government should reject a negotiated settlement. Jones described Churchill as a "cataract of boiling eloquence" and told him that "we are at war" and the battle should continue until the government won. (102)

John C. Davidson, the chairman of the Conservative Party, commented that Churchill was "the sort of man whom, if I wanted a mountain to be moved, I should send for at one. I think, however, that I should not consult him after he had moved the mountain if I wanted to know where to put it." (103) Neville Chamberlain found Churchill's approach unacceptable and wrote in his diary that "some of us are going to make a concerted attack on Winston... he simply revels in this affair, which he will continually treat and talk of as if it were 1914." (104)

Davidson, who had been put in overall charge of the government's media campaign, grew increasingly frustrated by Churchill's willingness to distort or suppress any item which might be vaguely favourable to "the enemy". Davidson argued that Churchill's behaviour became so extreme that he lost the support of the previously loyal Lord Birkenhead: "Winston, who had it firmly in his mind that anybody who was out of work was a Bolshevik; he was most extraordinary and never have I listened to such poppycock and rot." (105)

Churchill called for the government to seize union funds. This was rejected and Churchill was condemned for his "wild ways". John Charmley has argued that "Churchill had a sentimentalist upper-class view of grateful workers co-operating with their betters for the good of the nation; he neither understood, nor realised that he did not understand, the Labour movement. To have written about the TUC leaders as though they were potential Lenins and Trotskys said more about the state of Churchill's imagination than it did about his judgment." (106)

Walter Citrine, the general secretary of the Trade Union Congress (TUC), was desperate to bring an end to the General Strike. He argued that it was important to reopen negotiations with the government. His view was "the logical thing is to make the best conditions while our members are solid". Baldwin refused to talk to the TUC while the General Strike persisted. Citrine therefore contacted Jimmy Thomas, the general secretary of the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR), who shared this view of the strike, and asked him to arrange a meeting with Herbert Samuel, the Chairman of the Royal Commission on the Coal Industry. (107)

Without telling the miners, the TUC negotiating committee met Samuel on 7th May and they worked out a set of proposals to end the General Strike. These included: (i) a National Wages Board with an independent chairman; (ii) a minimum wage for all colliery workers; (iii) workers displaced by pit closures to be given alternative employment; (iv) the wages subsidy to be renewed while negotiations continued. However, Samuel warned that subsequent negotiations would probably mean a reduction in wages. These terms were accepted by the TUC negotiating committee, but were rejected by the executive of the Miners' Federation. (108)

Herbert Smith was furious with the TUC for going behind the miners back. One of those involved in the negotiations, John Bromley of the NUR, commented: "By God, we are all in this now and I want to say to the miners, in a brotherly comradely spirit... this is not a miners' fight now. I am willing to fight right along with them and suffer as a consequence, but I am not going to be strangled by my friends." Smith replied: "I am going to speak as straight as Bromley. If he wants to get out of this fight, well I am not stopping him." (109)

Walter Citrine wrote in his diary: "Miner after miner got up and, speaking with intensity of feeling, affirmed that the miners could not go back to work on a reduction in wages. Was all this sacrifice to be in vain?" Citrine quoted Cook as saying: "Gentleman, I know the sacrifice you have made. You do not want to bring the miners down. Gentlemen, don't do it. You want your recommendations to be a common policy with us, but that is a hard thing to do." (110)

Herbert Smith asked Arthur Pugh if the decision was "the unanimous decision of your Committee?" Pugh replied that it was the view that the General Strike should come to an end. Smith pleaded for further negotiations. However, Pugh was insistent: "That is it. That is the final decision, and that is what you have to consider as far as you are concerned, and accept it." (111)

On the 11th May, at a meeting of the Trade Union Congress General Committee, it was decided to accept the terms proposed by Herbert Samuel and to call off the General Strike. The following day, the TUC General Council visited 10 Downing Street and attempted to persuade the Government to support the Samuel proposals and to offer a guarantee that there would be no victimization of strikers.

Baldwin refused but did say if the miners returned to work on the current conditions he would provide a subsidy for six weeks and then there would be the pay cuts that the Mine Owners Association wanted to impose. He did say that he would legislate for the amalgamation of pits, introduce a welfare levy on profits and introduce a national wages board. The TUC negotiators agreed to this deal. As Lord Birkenhead, a member of the Government was to write later, the TUC's surrender was "so humiliating that some instinctive breeding made one unwilling even to look at them." (112)

In 1927 the British Government passed the Trade Disputes and Trade Union Act. This act made all sympathetic strikes illegal, ensured the trade union members had to voluntarily 'contract in' to pay the political levy to the Labour Party, forbade Civil Service unions to affiliate to the TUC, and made mass picketing illegal. As A. J. P. Taylor has pointed out: "The attack on Labour party finance came ill from the Conservatives who depended on secret donations from rich men." (113)

The legislation defined all sympathetic strikes as illegal, confining the right to strike to "the trade or industry in which the strikers are engaged". The funds of any union engaging in an illegal strike was liable in respect of civil damages. It also limited the right to picket, in terms so vague that almost any form of picketing might be liable to prosecution. As Julian Symons has pointed out: "More than any other single measure, the Trade Disputes Act caused hatred of Baldwin and his Government among organized trade unionists." (114)

Primary Sources

(1) Winston Churchill, memorandum to the Cabinet asking permission to use mustard gas (a gas that causes severe blistering and kills about ten per cent of those affected) in Mesopotamia (12th May 1919)

I do not understand this squeamishness about the use of gas... I am strongly in favour of using poisoned gases against uncivilised tribes. The moral effect should be so good that the loss of life should be reduced to a minimum... Gases can be used which cause great inconvenience and would leave a lively terror.

(2) Winston Churchill, memo to India Office (22nd May, 1919)

The objections of the India Office to the use of gas against natives (in Afghanistan) are unreasonable. Gas is a more merciful weapon than high explosive shell and compels an enemy to accept a decision with less loss of life than any other agency of war. The moral effect is also very great. There can be no conceivable reason why it should not be resorted to.

(3) Winston Churchill held a very low opinion of the Arabs and felt they deserved to lose their home in the Middle East to more advanced Europeans. He described the Arabs as acting like a "dog in a manger". He told the Peel Commission on 12th March, 1937.

I do not agree that the dog in a manger has the final right to the manger, even though he may have lain there for a very long time. I do not admit that right. I do not admit, for instance, that a great wrong has been done to the Red Indians of America, or the black people of Australia. I do not admit that a wrong has been done to these people by the fact that a stronger race, a higher grade race, or at any rate, a more worldly-wise race, to put it that way, has come in and taken their place."

(4) Giles Milton, Russian Roulette: How British Spies Thwarted Lenin's Global Plot (2013)

Bolsheviks soldiers fled as the green gas spread. Those who could not escape, vomited blood before losing consciousness. Other villages targeted included Chunova, Vikhtova, Pocha, Chorga, Tavoigor and Zapolki. During this period 506 gas bombs were dropped on the Russians. Lieutenant Donald Grantham interviewed Bolshevik prisoners about these attacks. One man named Boctroff said the soldiers "did not know what the cloud was and ran into it and some were overpowered in the cloud and died there; the others staggered about for a short time and then fell down and died". Boctroff claimed that twenty-five of his comrades had been killed during the attack. Boctroff was able to avoid the main "gas cloud" but he was very ill for 24 hours and suffered from "giddiness in head, running from ears, bled from nose and cough with blood, eyes watered and difficulty in breathing."

(5) Boris Johnson, The Churchill Factor (2014)

He (Churchill) was the man who decided that there should be such a thing as the state of Iraq, if you wanted to blame anyone for the current implosion, then of course you might point the finger at George W. Bush and Tony Blair and Saddam Hussein - but if you wanted to grasp the essence of the problem of that wretched state, you would have to look at the role of Winston Churchill.

(6) Peregrine Worsthorne, Why Winston Churchill is not Really a War Hero (22nd October, 2008)

Seldom has there been a statesman as good as glorifying war, and as indecently eager to wage war, as Winston Churchill. All his works demonstrate his love of war, glamorize its glories and minimize its horrors.

(7) Winston Churchill, Thoughts and Adventures (1932)

I found myself free a few months later to champion the anti-Socialist cause in the Westminster by-election, and so regained for a time at least the goodwill of all those strong Conservative elements, some of whose deepest feelings I share and can at critical moments express, although they have never liked or trusted me. But for my erroneous judgment in the General Election of 1923 I should have never have regained contact with the great party into which I was born and from which I had been severed by so many years of bitter quarrel...

Sometimes our mistakes and errors turn to great good fortune. When the Conservatives suddenly plunged into Protection in 1923, a dozen Liberal constituencies pressed me to be their candidate. And clearly Manchester was for every reason the battleground on which I should have fought. A seat was offered me there which, as it happened, I should in all probability have won. Instead, through some obscure complex, I chose to go off and fight against a Socialist in Leicester, where, being also attacked by the Conservatives, I was of course defeated. On learning of these two results in such sharp contrast, I could have kicked myself. Yet, as it turned out, it was the very fact that I was out of Parliament, free from all attachment and entanglement in any particular constituency, that enabled me to make an independent and unbiased judgment of the situation when the Liberals most unwisely and wrongly put the Socialist minority government for the first time into power, thus sealing their own doom.

Thus I found myself free a few months later to champion the anti-Socialist cause in the Westminster by-election, and so regained for a time at least the goodwill of all those strong Conservative elements, some of whose deepest feelings I share and can at critical moments express, although they have never liked or trusted me. But for my erroneous judgment in the General Election of 1923 I should have never have regained contact with the great party into which I was born and from which I had been severed by so many years of bitter quarrel.

When I survey in the light of these reflections the scene of my past life as a whole, I have no doubt that I do not wish to live it over again. Happy, vivid and full of interest as it has been, I do not seek to tread again the toilsome and dangerous path. Not even an opportunity of making a different set of mistakes and experiencing a different series of adventures and successes would lure me. How can I tell that the good fortune which has up to the present attended me with fair constancy would not be lacking at some critical moment in another chain of causation?

Let us be contented with what has happened to us and thankful for all we have been spared. Let us accept the natural order in which we move. Let us reconcile ourselves to the mysterious rhythm of our destinies, such as they must be in this world of space and time. Let us treasure our joys but not bewail our sorrows. The glory of light cannot exist without its shadows. Life is a whole, and good and ill must be accepted together. The journey has been enjoyable and well worth making - once.

(8) Winston Churchill, memorandum to Otto Niemeyer, a senior figure at the Treasury (22nd February, 1925)

The Treasury has never, it seems to me, faced the profound significance of what Mr Keynes calls `the paradox of unemployment amidst dearth'. The Governor shows himself perfectly happy in the spectacle of Britain possessing the finest credit in the world simultaneously with a million and a quarter unemployed. Obviously if these million and a quarter were usefully and economically employed, they would produce at least £100 a year a head, instead of costing up at least £50 a head in doles.

(9) Clive Ponting, Winston Churchill (1994)

Churchill's social conservatism was also apparent during discussions within the Government in 1925 over changes to unemployment insurance. The scheme that Churchill had favoured as President of the Board of Trade had collapsed after the war because of large-scale structural unemployment, particularly among trades that was not covered by the scheme. A benefit (the ‘dole') was first introduced for unemployed ex-servicemen, later extended to others and then made subject to a means-test in 1922. But as unemployment continued at high levels through the 1920s the Government became alarmed at the cost, and those subjected to the strict means-test found it highly demeaning. Churchill thought that far too many people were drawing the ‘dole'. On 30 April 1925 he spoke in the Commons of the "growing up of a habit of qualifying for unemployment relief" and the need for an enquiry. Three weeks later he told Tom Jones, the Deputy Secretary of the Cabinet, that "there should be an immediate stiffening of the administration, and the position should be made much more difficult for young unmarried men living with relatives, wives with husbands at work, aliens etc."

Four months later he wanted to go even further. In a letter to Steel-Maitland, the Minister of Labour, he suggested that when the legislation to pay for the dole expired in 1926, rather than reduce the benefit, as most of his colleagues wanted to do, they should abolish it altogether. He wrote: "It is profoundly injurious to the state that this system should continue; it is demoralising to the whole working class population... it is charitable relief; and charitable relief should never be enjoyed as a right." In future, if Churchill had his way, the huge number of unemployed families would have to depend on private charity once their insurance benefits were exhausted. The Government might make some donations to charities but money would only be given to "deserving cases" - Churchill did not elaborate on how they would be identified. Even so ‘no person under, say, 25 shall receive such relief without doing a full days work, which of course the State would have to organise and pay for'.

Churchill was convinced he was acting in the best interests of the unemployed. He told Steel-Maitland that by ‘proceeding on the present lines we are rotting the youth of the country and rupturing the mainsprings of its energies'. He hastened to reassure Baldwin the next day about his motivation: ‘I am thinking less about saving the exchequer than about saving the moral fibre of our working classes.'

Churchill did not get his way. The other members of the Government, regardless of any possible moral consequences, could not face the political impact of ending the ‘dole' at a time when over a million people were out of work. Nevertheless he was able to achieve the objective he referred to as less important – reducing the cost to the Exchequer by cutting the level of benefits for the unemployed. In 1926 the Treasury's contribution to the health and unemployment schemes was reduced by eleven per cent (to save £2.5 million on the health scheme) and a Royal Commission recommendation to extend the schemes was ignored. In 1927 the unemployment benefit for single men was reduced by a shilling a week. The test that the unemployed had to pass was also stiffened: they now had to prove that they were ‘genuinely seeking work' even if there were no jobs available. The Government was able to increase, as a matter of deliberate policy, the rejection rate from three per cent in 1924 to over eighteen per cent by 1927. In November 1925 he was also able to convince his colleagues that `to the utmost extent possible Government unemployment relief schemes should be closed down' in order to save money.

(10) Winston Churchill, letter to Arthur Steel-Maitland (19th September, 1925)

It is profoundly injurious to the state that this system should continue; it is demoralising to the whole working class population... it is charitable relief; and charitable relief should never be enjoyed as a right…. by proceeding on the present lines we are rotting the youth of the country and rupturing the mainsprings of its energies".

(11) J. R. Clynes, Memoirs (1937)

Churchill was, and has always remained, a soldier in mufti. He possesses inborn militaristic qualities, and is intensely proud of his descent from Marlborough. He cannot visualize Britain without an Empire, or the Empire without wars of acquisition and defence. A hundred years ago he might profoundly have affected the shaping of our country's history. Now, the impulses of peace and internationalism, and the education and equality of the working classes, leave him unmoved.

(12) David Low, Autobiography (1956)

As might be expected from his origins and temperament, Churchill was inwardly contemptuous of the 'common man' when the 'common man' sought to interfere in his (the 'common man's) own government; but bearing with the need to appear sympathetic and compliant to the popular will. In those days, whenever I heard Churchill's dramatic periods about democracy, I felt inclined to say: "Please define." His definition, I felt, would be something like "government of the people, for the people, by benevolent and paternal ruling-class chaps like me."

Churchill was witty and easy to talk to until I said that the Australians were an independent people who could not be expected to follow Britain without question. They were, in the case of new wars, for instance, not to be taken for granted, but would follow their own judgment.

Churchill was one of the few men I have met who even in the flesh give me the impression of genius. George Bernard Shaw is another. It is amusing to know that each thinks the other is overrated.

(13) Winston Churchill, Illustrated Sunday Herald (8th February, 1920)

The part played in the creation of Bolshevism and in the actual bringing about of the Russian Revolution by these international and for the most part atheistic Jews ... is certainly a very great one; it probably outweighs all others. With the notable exception of Lenin, the majority of the leading figures are Jews. Moreover, the principal inspiration and driving power comes from Jewish leaders ... The same evil prominence was obtained by Jews in (Hungary and Germany, especially Bavaria).

Although in all these countries there are many non-Jews every whit as bad as the worst of the Jewish revolutionaries, the part played by the latter in proportion to their numbers in the population is astonishing. The fact that in many cases Jewish interests and Jewish places of worship are excepted by the Bolsheviks from their universal hostility has tended more and more to associate the Jewish race in Russia with the villainies which are now being perpetrated.

(14) Philip Snowden, An Autobiography (1934)

The most surprising of the Ministerial appointments made by Mr. Baldwin was the constituted his government in November 1924 was the selection of Mr. Winston Churchill as Chancellor of the Exchequer. What induced Mr. Baldwin to offer Mr. Churchill this important post still remains an inscrutable mystery.

As an ex-Chancellor it fell to me to lead the Opposition in the Budget debates, and I found Mr. Churchill a foe worthy of my steel. Mr. Churchill, during these years, gradually developed as a Parliamentary debater. He learnt to rely less on careful preparation of his speeches and more upon spontaneous effort. However much one may differ from Mr. Churchill, one is compelled to like him for his finer qualities. There is an attractiveness in everything he does. His high spirits are irrepressible. Mr. Churchill was as happy facing a Budget deficit as in distributing a surplus. He is an adventurer, a soldier of fortune.

(15) Kingsley Martin, Father Figures (1966)

The General Strike of 1926 was an unmitigated disaster. Not merely for Labour but for England. Churchill and other militants in the cabinet were eager for a strike, knowing that they had built a national organization in the six months' grace won by the subsidy to the mining industry. Churchill himself told me this on the first occasion I met him in person. I asked Winston what he thought of the Samuel Coal Commission. When Winston said that the subsidy had been granted to enable the Government to smash the unions, unless the miners had given way in the meantime, my picture of Winston was confirmed.