On this day on 30th June

On this day in 1337 Eleanor de Clare died. Gilbert, 10th Earl de Clare was only 23 years old when he was killed at Bannockburn in 1314. Gilbert did not have any children and so his death brought an end to the male line of the Clare family. The estates should have been immediately divided between Gilbert's three sisters, Eleanor, Margaret and Elizabeth.

At first, Edward II refused permission for the sisters to inherit this land. The king knew that these estates would give great power to the women's husbands. It was only when Edward was convinced that these men would support him in his struggle with his barons, that he gave permission for the women to inherit the estates.

In the 14th century it was common for the king to be involved in selecting husbands for the daughters of his most powerful barons. Eleanor, the eldest daughter, was only 14 years old when she was forced to marry the king's main adviser, Hugh Despenser, in 1306. As Eleanor was married to one of his most loyal subjects, Edward was willing to allow her to inherit her share of the Clare estates.

Margaret was more of a problem as she was a widow when Gilbert was killed at Bannockburn. In 1307 Edward II had arranged for 14 year old Margaret to marry his favourite knight, Piers Gaveston. Five years later Gaveston was murdered by the king's opponents. Before Margaret was allowed to inherit her share of the Clare estates in 1317 she had to agree to marry Hugh de Audley, one of the king's loyal knights.

Elizabeth de Clare, the youngest daughter, was also a widow in 1314. Elizabeth married John de Burgh, son of the Earl of Ulster, when she was 14 but he died five years later. While Elizabeth was waiting for her inheritance, the marcher lord, Theobald Verdun kidnapped her and took her to his castle at Alton where he married her against her will. However, Theobald Verdun died six months after the wedding.

Edward II decided to keep Elizabeth in custody at Bristol Castle. The following year, she was granted her share of the Clare inheritance when she agreed to marry Roger Damory, another one of the king's supporters.

In 1322 Roger Damory changed sides and fought for the Earl of Lancaster at Boroughbridge. Damory was captured during the battle and was later executed for treason. Elizabeth had remained loyal to Edward and she was allowed to keep her estates. The king now decided it would be better if Elizabeth remained a widow.

In 1326 Eleanor's husband, Hugh Despenser, was captured and executed by barons opposed to the king. The following year Eleanor was kidnapped and raped by a knight called William la Zouche. The punishment for rape was death but as Zouche was one of Edward's most loyal knights, the king refused to take action against him. Eleanor was forced to accept William la Zouche as her husband.

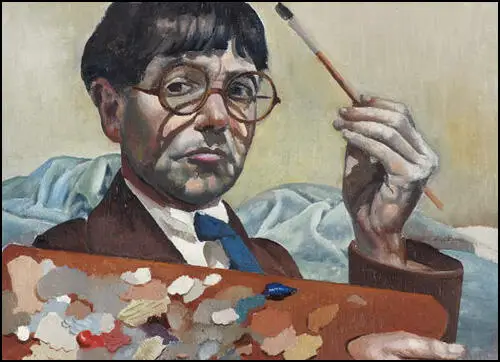

On this day in 1891 artist Stanley Spencer, the son of William Spencer, a teacher of music, was born in Cookham, Berkshire. He was the seventh son in a family of eleven children, of whom two died in infancy. The family lived in Fernlea, a semi-detached villa in Cookham High Street, that had been built by Stanley's grandfather, a local master builder.

When Spencer was seventeen he entered the Slade School of Fine Art at University College. Other students at the Slade at that time included Christopher Nevinson, Paul Nash, David Bomberg, William Roberts, Mark Gertler, Dora Carrington and Edward Wadsworth.

Spencer's skill as a artist is evident in early works such as The Fairy on the Waterlily Leaf (1910). One of his tutors, Henry Tonks argued that Spencer had the most original mind of any student he had the pleasure of teaching. At the Slade he won the Composition Prize with his painting The Nativity (1912). However, as his biographer, Fiona MacCarthy, points out: "His four years at the Slade were not altogether happy. He was marked out as a misfit by his physical appearance: his diminutiveness (he was only 5 feet 2 inches), his heavy fringe, and pudding-basin haircut. His aura of other-worldliness was enhanced by the fact that he commuted daily by train from Berkshire. He was known jeeringly as Cookham, and terrified by being put upside-down in a sack."

On the outbreak of the First World War, Spencer joined the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC). He worked at Beaufort Hospital in Bristol where he helped to nurse soldiers wounded on the Western Front. On 7th December 1915 he wrote to his friend, Henry Lamb: "Two hundred patients or more would arrive in the middle of the night - this was disquieting and disturbing. One had just got used to the patients one had; had mentally and imaginatively visualized them. I have to move patients with their beds from one ward to another or perhaps to the theatre."

In August 1916 he was sent as part of the 68th Field Ambulance unit to Salonika, a port being defended by General Maurice Sarrail and 150,000, British and French soldiers. In August 1917 he volunteered for the infantry, joining the 7th battalion, the Royal Berkshires, and spending several months in the front line. He later recalled: "Our activities consisted of outpost duty and patrolling the wire at night and during the daytime doing odd fatigues, just outside our dugouts. In the evening just before sunset, the Bulgars started a barrage. The shells dropped uncomfortably near and I was glad when getting into the outposts, we were able to take cover in a communication trench."

On one occasion he went out on patrol with one of the officers: "I went out with a captain and he was hit and sank to the ground. His hand went up to his neck and I saw a gaping bullet wound in it. I bandaged the wound the best I could and called for stretcher-bearers. I helped to support the captain, who was paralyzed." Spencer was devastated when he heard him whisper to another officer: "Understand, Spencer is not a fool; he is a damned good man." Spencer was shocked by what he heard: "What's all this? Who has been saying otherwise?"

In May, 1918, Spencer was asked to contribute to the government's planned Hall of Remembrance. The letter asked him to to paint a picture about his experiences in Salonika. However, it was not until after the Armistice that Spencer painted Travoys Arriving with Wounded at a Dressing Station at Smol, Macedonia, September 1916.

After the war Stanley Spencer was commissioned by Louis and Mary Behrend in memory of Mrs Behrend's brother Lieutenant Henry Willoughby Sandham to paint a decorative mural of army life during the First World War. Sandham had died in 1919 after an illness contracted in in Salonika. The nineteen paintings appeared in the Sandham Memorial Chapel in Burghclere, Hampshire. The work was painted as a modern parallel to Giotto's Arena Chapel in Padua. The cycle of scenes from everyday military life culminates in the altarpiece, Resurrection of the Soldiers.

Stanley Spencer painted The Resurrection, between 1924 and 1926 in a studio in Hampstead borrowed from Henry Lamb. When it was showed for the first time in February 1927 The Times critic described it as "the most important picture painted by any English artist in the present century… It is as if a Pre-Raphaelite had shaken hands with a Cubist". The painting was purchased by Joseph Duveen who then gave it to the Tate Gallery.

One critic argued that "Spencer believed that the divine rested in all creation. He saw his home town of Cookham as a paradise in which everything is invested with mystical significance. The local churchyard here becomes the setting for the resurrection of the dead. Christ is enthroned in the church porch, cradling three babies, with God the Father standing behind. Spencer himself appears near the centre, naked, leaning against a grave stone; his fiancée Hilda lies sleeping in a bed of ivy. At the top left, risen souls are transported to Heaven in the pleasure steamers that then ploughed the Thames."

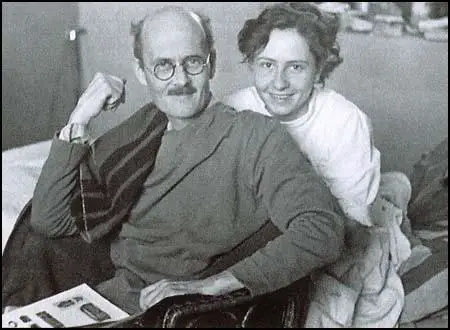

While working on this cycle almost continuously between 1926 and 1932, Spencer lived in a cottage alongside the chapel with his wife, Hilda Carline (1889–1950) and their two daughters: Shirin (b. 1925) and Unity (b. 1930). The cultural historian, Fiona MacCarthy has argued: "The narrative of Stanley Spencer's war - the wounded arriving at Beaufort, the training camp at Tweseldown, the day-to-day routines of service in Macedonia - climaxes in the crowded, joyful central composition The Resurrection of the Soldiers covering the whole east wall. It is a highly personal sequence that transcends the anecdotal, treating the grand themes of glory and redemption in an extraordinary fusion of grandiloquence and homeliness."

After completing the Sandham Memorial Chapel Spencer and his young family moved to Lindworth, a house in Cookham. However, it was not a happy marriage and her passionate Christian Science principles seriously impaired their sex life. During this period Spencer became friendly with Patricia Preece who lived in Cookham with her friend and sexual partner Dorothy Hepworth. Hilda's refusal to accede to demands for a ménage à trois demanded by Spencer forced her eventually to file for a divorce which was granted on 25th May 1937.

Spencer married Preece four days later. They never lived together and according to Tee A. Corinne: "Spencer went into debt giving Preece money, clothing, and jewelry... Spencer then married Preece, but when he attempted to consummate the marriage, Preece immediately fled to Hepworth. Although Spencer and Preece never lived together as man and wife, they never divorced." Although the marriage was unconsummated, it did produce some remarkable nude portraits including Nude: Patricia Preece (1935), Self Portrait with Patricia Preece (1936) and Double Nude Portrait: the Artist and his Second Wife (1937).

Spencer continued to paint pictures of his marriage to Hilda Carline. This included Domestic Scenes: At the Chest of Draws (1936), The Beatitudes of Love (1937) and Romantic Meeting (1938). He also wrote her many letters but following a mental breakdown she was admitted to Banstead Mental Hospital in Epsom. Spencer gave his house in Cookham to Patricia Preece who rented it out in 1938, and he was forced to move to a rented room in Adelaide Road, Hampstead. Over the next few years he produced a series of paintings entitled Christ in the Wilderness (1939–53).

Soon after the outbreak of the Second World War the War Artists' Advisory Committee commissioned Spencer to record shipbuilding on the River Clyde. As his biographer, Fiona MacCarthy, points out: "His work was based at Lithgow's shipyard in Port Glasgow on the Firth of Clyde, concentrated on merchant ships under construction, and Spencer spent extended periods in Scotland during and immediately after the war. Spencer's war work came as a reprieve from his anxious isolation. He was able to immerse himself in the day-to-day activities of ordinary working people, intimately involved in the highly skilled processes of making with which he had always felt an innate sympathy. The Clyde shipbuilding paintings were conceived on an epic scale. Spencer's proposal was for a three-tier frieze 70 feet long. Eight of the projected thirteen canvases had been completed by the time the war artists were disbanded in 1946."

In September 1945 Spencer returned to Cookham, settling in Cliveden View, a small house belonging to his brother Percy Spencer. His former wife, Hilda Carline, died of breast cancer in 1950. He was devastated by the news and "he continued to write her his long, hectic, erotic, often incoherent letters." Over the next few years he completed a new cycle, Christ Preaching at Cookham Regatta (1955-1959).

In July 1959 he was knighted by Elizabeth II. His wife, Patricia Preece, now arrived back on the scene and took the title, Lady Spencer. Five months later, on 14 December 1959, Stanley Spencer died of cancer in the Canadian Red Cross Memorial Hospital at Taplow.

On this day in 1908 Women Social & Political Union campaigner Charlotte Marsh was arrested with Elsie Howey and charged with obstructing the police. She was found guilty and sentenced to a month's imprisonment in Holloway Prison.

A wealthy supporter of the WSPU donated money to buy Emmeline Pankhurst a motor car so that she could travel the country in comfort. According to Martin Pugh, the author of The Pankhursts (2001), Marsh applied for the job of driving the car. However, Vera Holme, got the post, but there were occasions when she worked as Pankhurst's chauffeur.

On 22nd September 1909 she was arrested along with Rona Robinson, Laura Ainsworth and Mary Leigh while disrupting a public meeting being held by Herbert Asquith. As Michelle Myall has pointed out: "The police attempted to move the two women by, among other methods, turning a hosepipe on them and throwing stones. However, Charlotte Marsh and Mary Leigh proved to be formidable opponents and were only brought down from the roof when three policeman dragged them down."

On 22nd September 1909 she was arrested along with Rona Robinson, Laura Ainsworth and Mary Leigh while disrupting a public meeting being held by Herbert Asquith. As Michelle Myall has pointed out: "The police attempted to move the two women by, among other methods, turning a hosepipe on them and throwing stones. However, Charlotte Marsh and Mary Leigh proved to be formidable opponents and were only brought down from the roof when three policeman dragged them down."

Marsh, Robinson, Ainsworth and Leigh were all sentenced to two weeks' imprisonment. They immediately decided to go on hunger-strike, a strategy developed by Marion Wallace-Dunlop a few weeks earlier. Wallace-Dunlop had been immediately released when she had tried this in Holloway Prison, but the governor of Winson Green Prison, was willing to feed the three women by force.

C.P. Scott wrote to Asquith complaining of the "substantial injustice of punishing a girl like Miss Marsh with two months hard labour plus forcible feeding." According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999): "The Prison Visiting Committee reported that at first she had to be fed by placing food in the mouth and holding the nostrils, but that she later took food from a feeding cup." Votes for Women, on her release, reported that she had been fed by tube 139 times. Although her father was seriously ill, the authorities refused to release Marsh early. Marsh left Winson Green Prison on 9th December, 1909. She immediately dashed to her family home in Newcastle upon Tyne but he was already unconscious and he died a few days later.

In February 1910 Charlotte Marsh was WSPU organiser in Oxford. She then moved onto Portsmouth and in September 1910 she ran a WSPU holiday campaign in Southsea. During this period a fellow suffragette described her as "a tall young woman, of quiet, resolute bearing." The Times reported that she was "strikingly beautiful with blue eyes and long corn-coloured hair." Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence described her as one of the "saints of the Church Militant".

Marsh visited Eagle House near Batheaston in April 1911 with Annie Kenney and Laura Ainsworth. Their host, was Mary Blathwayt, a fellow member of the WSPU. Her father Colonel Linley Blathwayt planted a tree, a Picea Polita, in her honour in his suffragette arboretum in a field adjacent to the house. Mary's mother, Emily Blathwayt, commented in her diary: "Miss Marsh planted her tree. She greatly dislikes her first name Charlotte and all her friends call her Charlie. Her label will be C. A. L. Marsh. (She also goes by the name of Calm). We liked very much what we saw of her. She is very fair with light hair and a pretty face. She is very tall ... She has a wonderful constitution and seems very well after all she has gone through. She has begun the late custom of not taking meat or chicken. She seems a very nice quiet girl."

In March 1912 Charlotte Marsh took part in a window-smashing campaign in London. It is claimed that she alone smashed nine windows in the Strand during this demonstration. Emily Blathwayt wrote in her diary: "Linley had a nice letter from C. A. L. Marsh in Holloway awaiting her trial as they all refused bail. His birthday letter to her begging her not to take part in violence followed her there. Like the rest, they all think it their duty to take a large share of suffering." As she had previous convictions she was sentenced to six months' in Aylesbury Prison. She took part in the hunger-strike and was forcibly fed.

On her release she was sent to Switzerland to recuperate. On her return she was WSPU organiser in Nottingham. She also spent time in London working alongside Grace Roe. In June 1913 she was the Standard Bearer at the funeral of Emily Wilding Davison.

On 4th August, 1914, England declared war on Germany. The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort.

Emmeline Pankhurst announced that all militants had to "fight for their country as they fought for the vote." Ethel Smyth pointed out in her autobiography, Female Pipings for Eden (1933): "Mrs Pankhurst declared that it was now a question of Votes for Women, but of having any country left to vote in. The Suffrage ship was put out of commission for the duration of the war, and the militants began to tackle the common task."

Charlotte Marsh initially accepted this policy and worked as a motor mechanic before becoming the chauffeur of David Lloyd George "accepting his suggestion that the relationship would promote the victory of the cause of women's enfranchisement". She also worked as a member of the Women's Land Army in Surrey.

Marsh became increasingly critical of the way that Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst were running the WSPU during the First World War. Questions were also being asked about the funds of the WSPU. According to Martin Pugh, the author of The Pankhursts (2001): "The accounts had not been rendered since February 1914 when an annual income of £46,000 had been recorded. Moreover, the conviction that this money had been misappropriated for the Pankhursts' own purposes continued to rankle for many years." In March 1916, Charlotte Marsh set up the Independent WSPU.

After the war Marsh worked for Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. According to Elizabeth Crawford: "She then spent some time with the Department of Social Work in San Francisco and then with the Overseas Settlement League. By 1934 she was working with the Public Assistance Department of the London County Council." Marsh was also, along with Margaret Haig Thomas and Theresa Garnett, an executive member of the Six Point Group. She was also vice-president of the Suffragette Fellowship.

Charlotte Marsh, who never married, died at her home, 31 Copse Hill, Wimbledon, on 21st April 1961.

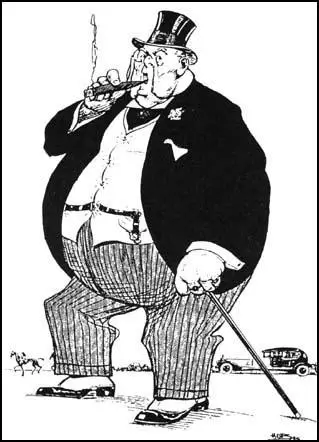

On this day in 1925 UK mineowners announce that they intended to reduce the miner's wages. Will Paynter later commented: "The coal owners gave notice of their intention to end the wage agreement then operating, bad though it was, and proposed further wage reductions, the abolition of the minimum wage principle, shorter hours and a reversion to district agreements from the then existing national agreements. This was, without question, a monstrous package attack, and was seen as a further attempt to lower the position not only of miners but of all industrial workers."

On 23rd July, 1925, Ernest Bevin, the general secretary of the Transport & General Workers Union (TGWU), moved a resolution at a conference of transport workers pledging full support to the miners and full co-operation with the General Council in carrying out any measures they might decide to take. A few days later the railway unions also pledged their support and set up a joint committee with the transport workers to prepare for the embargo on the movement of coal which the General Council had ordered in the event of a lock-out." It has been claimed that the railwaymen believed "that a successful attack on the miners would be followed by another on them."

In an attempt to avoid a General Strike, the prime minister, Stanley Baldwin, invited the leaders of the miners and the mine owners to Downing Street on 29th July. The miners kept firm on what became their slogan: "Not a minute on the day, not a penny off the pay". Herbert Smith, the president of the Miners' Federation of Great Britain, told Baldwin: "We have now to give". Baldwin insisted there would be no subsidy: "All the workers of this country have got to take reductions in wages to help put industry on its feet."

The following day the General Council of the Trade Union Congress triggered a national embargo on coal movements. On 31st July, the government capitulated. It announced an inquiry into the scope and methods of reorganization of the industry, and Baldwin offered a subsidy that would meet the difference between the owners' and the miners' positions on pay until the new Commission reported. The subsidy would end on 1st May 1926. Until then, the lockout notices and the strike were suspended. This event became known as Red Friday because it was seen as a victory for working class solidarity.

Will Paynter later commented: "The coal owners gave notice of their intention to end the wage agreement then operating, bad though it was, and proposed further wage reductions, the abolition of the minimum wage principle, shorter hours and a reversion to district agreements from the then existing national agreements. This was, without question, a monstrous package attack, and was seen as a further attempt to lower the position not only of miners but of all industrial workers." (11)

On 23rd July, 1925, Ernest Bevin, the general secretary of the Transport & General Workers Union (TGWU), moved a resolution at a conference of transport workers pledging full support to the miners and full co-operation with the General Council in carrying out any measures they might decide to take. A few days later the railway unions also pledged their support and set up a joint committee with the transport workers to prepare for the embargo on the movement of coal which the General Council had ordered in the event of a lock-out." (12) It has been claimed that the railwaymen believed "that a successful attack on the miners would be followed by another on them." (13)

In an attempt to avoid a General Strike, the prime minister, Stanley Baldwin, invited the leaders of the miners and the mine owners to Downing Street on 29th July. The miners kept firm on what became their slogan: "Not a minute on the day, not a penny off the pay". Herbert Smith, the president of the Miners' Federation of Great Britain, told Baldwin: "We have now to give". Baldwin insisted there would be no subsidy: "All the workers of this country have got to take reductions in wages to help put industry on its feet." (14)

The following day the General Council of the Trade Union Congress triggered a national embargo on coal movements. On 31st July, the government capitulated. It announced an inquiry into the scope and methods of reorganization of the industry, and Baldwin offered a subsidy that would meet the difference between the owners' and the miners' positions on pay until the new Commission reported. The subsidy would end on 1st May 1926. Until then, the lockout notices and the strike were suspended. This event became known as Red Friday because it was seen as a victory for working class solidarity. (15)

Herbert Smith pointed out that the real battle was to come: "We have no need to glorify about a victory. It is only an armistice, and it will depend largely how we stand between now and May 1st next year as an organisation in respect of unity as to what will be the ultimate results. All I can say is, that it is one of the finest things ever done by an organisation."

Red Friday was a great success for Herbert Smith and Arthur J. Cook. However, Margaret Morris has argued that they had a difficult relationship: "Smith was temperamentally and politically the antithesis of Cook. Where Cook was emotional and voluble, Smith was dour and short of words. He was an old-style union leader, used to dominating the miners in Yorkshire... Relations between Smith and Cook were not always harmonious; neither of them really trusted the other's judgement, but each could respect that the other was dedicated to serving the miners. Neither of them was a very good negotiator: Cook was too excitable, and Smith perhaps a little too defensive in his tactics."

pointed out that the real battle was to come: "We have no need to glorify about a victory. It is only an armistice, and it will depend largely how we stand between now and May 1st next year as an organisation in respect of unity as to what will be the ultimate results. All I can say is, that it is one of the finest things ever done by an organisation."

Red Friday was a great success for Smith and Arthur J. Cook. However, Margaret Morris has argued that they had a difficult relationship: "Smith was temperamentally and politically the antithesis of Cook. Where Cook was emotional and voluble, Smith was dour and short of words. He was an old-style union leader, used to dominating the miners in Yorkshire... Relations between Smith and Cook were not always harmonious; neither of them really trusted the other's judgement, but each could respect that the other was dedicated to serving the miners. Neither of them was a very good negotiator: Cook was too excitable, and Smith perhaps a little too defensive in his tactics."

Trade Union Unity Magazine (1925)

On this day in 1934 the Night of the Long Knives takes place. At around 6.30 in the morning, Adolf Hitler arrived at the hotel in a fleet of cars full of armed Schutzstaffel (SS) men. (30) Erich Kempka, Hitler's chauffeur, witnessed what happened: "Hitler entered Röhm's bedroom alone with a whip in his hand. Behind him were two detectives with pistols at the ready. He spat out the words; Röhm, you are under arrest. Röhm's doctor comes out of a room and to our surprise he has his wife with him. I hear Lutze putting in a good word for him with Hitler. Then Hitler walks up to him, greets him, shakes hand with his wife and asks them to leave the hotel, it isn't a pleasant place for them to stay in, that day. Now the bus arrives. Quickly, the SA leaders are collected from the laundry room and walk past Röhm under police guard. Röhm looks up from his coffee sadly and waves to them in a melancholy way. At last Röhm too is led from the hotel. He walks past Hitler with his head bowed, completely apathetic."

Edmund Heines was found in bed with his chauffeur and along with Röhm were taken to Stadelheim Prison. At the Munich railroad station, the SA leaders were beginning to arrive. As they alighted from the incoming trains they were taken into custody by SS troops. It is estimated that about 200 senior SA officers were arrested during what became known as the Night of the Long Knives.

One of Ernst Röhm's boyfriends, Karl Ernst, and the head of the SA in Berlin, had just married and was driving to Bremen with his bride to board a ship for a honeymoon in Madeira. His car was overtaken by Schutzstaffel (SS) gunman, who fired on the car, wounding his wife and his chauffeur. Ernst was taken back to SS headquarters and executed later that day.

A large number of the SA officers were shot as soon as they were captured but Adolf Hitler decided to pardon Röhm because of his past services to the movement. However, after much pressure from Göring and Himmler, Hitler agreed that Röhm should die. Himmler ordered Theodor Eicke to carry out the task. Eicke and his adjutant, Michael Lippert, travelled to Stadelheim Prison in Munich where Röhm was being held. Eicke placed a pistol on a table in Röhm's cell and told him that he had 10 minutes in which to use the weapon to kill himself. Röhm replied: "If Adolf wants to kill me, let him do the dirty work."

According to Paul R. Maracin, the author of The Night of the Long Knives: Forty-Eight Hours that Changed the History of the World (2004): "Ten minutes later, SS officers Michael Lippert and Theodor Eicke appeared, and as the embittered, scar-faced veteran of verdun defiantly stood in the middle of the cell stripped to the waist, the two SS officers riddled his body with revolver bullets." Eicke later claimed that Röhm fell to the floor moaning "Mein Führer". (35)

Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary: "Executions nearly finished. A few more are necessary. That is difficult, but necessary... It is difficult, but is not however to be avoided. There must be peace for ten years. The whole afternoon with the Führer. I can't leave him alone. He suffers greatly, but is hard. The death sentences are received with the greatest seriousness. All in all about 60." (36)

On this day in 1934 German politician Gregor Strasser was murdered. Gregor Strasser, the brother of Otto Strasser, was born at Geisenfeld on 31st May, 1892. Strasser joined the German Army and during the First World War he advanced to the rank of lieutenant and won the Iron Cross (First and Second Classes) for bravery.

Strasser was a member of the Freikorps before joining the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP). He took part in the Beer Hall Putsch and after its failure was briefly imprisoned. On his release he sold his apothecary shop and used the money to devote himself wholly to the party.

Gregor Strasser moved to North Germany where he quickly became one of the most important figures in Sturm Abteilung (SA). He developed a large following and became leader of the revolutionary wing of the NSDAP. Strasser was a committed socialist who believed in "undiluted socialist principles". Like Ernst Roehm, opposed Hitler's policy of trying to win the support of the country's major industrialists. His outspoken views caused a deep rift with Hitler and other leaders of the party.

In 1924 he joined forces with his brother, Otto Strasser, to establish the Berliner Arbeiter Zeitung, a left-wing newspaper, that advocated world revolution. It also supported Lenin and the Bolshevik government in the Soviet Union. Later that year, Strasser was elected to the Bavarian Legislature. His biographer, Louis L. Snyder, has argued: "In this capacity he proved to be an able organizer, an indefatigable if weak speaker, a shrewd politician, and a lover of action.... Using his parliamentary immunity to protect him from libel suits and holding a free railway pass, he turned his energy to seeking the highest post in the National Socialist Party. He would push Hitler aside and replace him. Strasser regarded himself as a proud intellectual who had far more to offer the party than the emotional and unstable Hitler."

In one speech Strasser argued: "The rise of National Socialism is the protest of a people against a State that denies the right to work. If the machinery for distribution in the present economic system of the world is incapable of properly distributing the productive wealth of nations, then that system is false and must be altered. The important part of the present development is the anti-capitalist sentiment that is permeating our people."

Ernst Hanfstaengel has claimed that Adolf Hitler was deeply jealous of Gregor Strasser. "He was the one potential indeed actual rival within the party. He had made the Rhineland his fief. I remember during one tour through the Ruhr towns seeing Strasser's name plastered up against the wall of every railway underpass. He was obviously quite a figure in the land. Hitler looked away."

Rudolf Olden, the author of Hitler the Pawn (1936) has pointed out: "Gregor Strasser, a chemist of Landshut in Bavaria, had borne the brunt of the agitation in North Germany.... In one year he made one hundred and eighty speeches and was for a long time better known and respected than Hitler among the volkisch groups on the further side of the Main. He had sold his pharmacy and invested his capital in politics. The first National Socialist papers that appeared in Berlin were started with his money. Strasser was a useful helper, but an awkward subordinate. He considered himself a Socialist, although his Socialism was little else than Bavarian self-assurance... At one time something that looked very much like a conflict of opposing schools of thought existed in the National Socialist Party."

On 14th February, 1926, at the NSDAP annual conference, Strasser called for the destruction of capitalism in any way possible, including cooperation with the Bolsheviks in the Soviet Union. At the conference Joseph Goebbels supported Strasser but once he realised the majority supported Adolf Hitler over Strasser, he changed sides. From this point on Strasser began to call Goebbels "the scheming dwarf".

Hitler was deeply jealous of Gregor Strasser. He was the one potential indeed actual rival within the party. He had made the Rhineland his fief. I remember during one tour through the Ruhr towns seeing Strasser's name plastered up against the wall of every railway underpass. He was obviously quite a figure in the land. Hitler looked away. There was no comment about "Strasser seems to be doing well", or any approving sign.

Herman Rauschning was close to Strasser. "In Danzig and in most of Northern Germany, Gregor Strasser had always been more esteemed than Hitler himself. Hitler's nature was incomprehensible to the North German. The big, broad Strasser, on the other hand, a hearty eater and a hearty drinker too, slightly self-indulgent, practical, clear-headed, quick to act, without bombast and bathos, with a sound peasant judgment: this was a man we could all understand."

In December 1932, Paul von Hindenburg invited Kurt von Schleicher to become chancellor and invited Strasser to be his deputy. Ernst Hanfstaengel has pointed out: "His plan was to split off the Strasser wing of the Nazi Party in a final effort to find a majority with the Weimar Socialists and Centre. The idea was by no means so ill-conceived and amidst the momentary demoralization and monetary confusion in the Nazi ranks, very nearly came off." Adolf Hitler and Hermann Goering challenged the move claiming it was an attempt to create a split in the NSDAP.

In order to maintain party unity Strasser resigned all party positions and found work in a large chemical firm. He told a friend: "Dr. Martin, I am a man marked by death. We shall not be able to go on seeing each other for long and in your own interests I suggest you do not come here any more. Whatever happens, mark what I say: From now on Germany is in the hands of an Austrian who is a congenital liar, a former officer who is a pervert, and a clubfoot. And I tell you the last is the worst of them all. This is Satan in human form."

In 1933 Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany. Industrialists such as Albert Voegler, Gustav Krupp, Alfried Krupp, Fritz Thyssen and Emile Kirdorf, who had provided the funds for the Nazi victory, were unhappy with people such as Strasser and Ernst Roehm, who argued that the real revolution had still to take place. Many people in the party also disapproved of the fact that Roehm and many other leaders of the SA were homosexuals.

On 29th June, 1934. Hitler, accompanied by the Schutzstaffel (SS), arrived at Bad Wiesse, where he personally arrested Ernst Roehm. During the next 24 hours 200 other senior SA officers were arrested on the way to the meeting. Erich Kempka, Hitler's chauffeur, witnessed what happened: "Hitler entered Roehm's bedroom alone with a whip in his hand. Behind him were two detectives with pistols at the ready. He spat out the words; Roehm, you are under arrest. Roehm's doctor comes out of a room and to our surprise he has his wife with him. I hear Lutze putting in a good word for him with Hitler. Then Hitler walks up to him, greets him, shakes hand with his wife and asks them to leave the hotel, it isn't a pleasant place for them to stay in, that day. Now the bus arrives. Quickly, the SA leaders are collected from the laundry room and walk past Roehm under police guard. Roehm looks up from his coffee sadly and waves to them in a melancholy way. At last Roehm too is led from the hotel. He walks past Hitler with his head bowed, completely apathetic."

A large number of the SA officers were shot as soon as they were captured but Adolf Hitler decided to pardon Roehm because of his past services to the movement. However, after much pressure from Hermann Goering and Heinrich Himmler, Hitler agreed that Roehm should die. At first Hitler insisted that Roehm should be allowed to commit suicide but, when he refused, Ernst Roehm was killed by two SS men.

On 30th June 1934 Gregor Strasser was arrested by the Gestapo as part of the purge of the socialists. He was taken to Gestapo Headquarters where he was shot in the back of the head. The purge of the SA was kept secret until it was announced by Hitler on 13th July. It was during this speech that Hitler gave the purge its name: Night of the Long Knives (a phrase from a popular Nazi song). Hitler claimed that 61 had been executed while 13 had been shot resisting arrest and three had committed suicide. Others have argued that as many as 400 people were killed during the purge. In his speech Hitler explained why he had not relied on the courts to deal with the conspirators: "In this hour I was responsible for the fate of the German people, and thereby I become the supreme judge of the German people. I gave the order to shoot the ringleaders in this treason."

On this day in 1941 it is reported that Tom Winteringham has been forced to resign from the leadership of Britain's Home Guard Training School. Wintringham, a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, completely disagreed with the about the Second World War. He argued that the new party line was "disastrous, wrong, non-Marxist, contrary to the interests of the working-class and of the revolution." As Hugh Purcell has pointed out: ""He disliked increasingly the subservience of the Communist Party of Great Britain to the Comintern, in effect to Russian foreign policy, and he became vitriolic when the Party stayed out of World War Two after Stalin's peace pact with Hitler in the summer of 1939."

Tom Hopkinson recruited Wintringham to work for the Picture Post. He also wrote a regular column for the Daily Mirror, Tribune and the New Statesman. This gave him a readership of several million. He also wrote several pamphlets on the war effort including New Ways of War (1940), Freedom is Our Weapon (1941) and Politics of Victory (1941).

In New Ways of War he wrote: "Knowing that science and the riches of the earth make possible an abundance of material things for all, and trusting our fellows and ourselves to achieve that abundance after we have won, we are willing to throw everything we now possess into the common lot, to win this fight. We will allow no personal considerations of rights, privileges, property, income, family or friendship to stand in our way. Whatever the future may hold we will continue our war for liberty."

Wintringham "believed that war provided the best opportunity for revolution and that a revolution was necessary for fascism to be defeated." George Orwell agreed with him: "We are in a strange period of history, in which a revolutionary has to be a patriot and a patriot has to be a revolutionary." Both men had been deeply influenced by their experiences of fighting in the Spanish Civil War.

In October 1939, Winston Churchill suggested to Sir John Anderson, the head of Air Raid Precautions (ARP), that a Home Guard of men aged over forty should be formed. Anderson agreed with Churchill's suggestion but it was not until the German Army had launched its Western Offensive that action was taken and on 14th May, 1940, Anthony Eden appealed on radio for men to become Local Defence Volunteers (LDV). In the broadcast Eden asked that volunteers should be aged be aged between 40 and 65 and should be able to fire a rifle or shotgun. By the end of June nearly one and a half a million men had been recruited.

Wintringham wrote several articles where he argued that the Home Guard should be trained in guerrilla warfare. Tom Hopkinson and Edward Hulton came up with the idea private training school for the Home Guard. On 10th July 1940, Wintringham was appointed as director of the Osterley Park Training School at Isleworth, Middlesex. In the first three months he trained 5,000 in the rudiments of guerrilla warfare.

In 1940 Wintringham wrote a 20,000 word pamphlet entitled How to Reform the Army. Over the next few months over 10,000 copies were sold and he was consulted by Sir Ronald Adam, the Deputy Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Sir John Brown, the Deputy Adjutant-General and Major General Augustus Thorne, the Commander of the Brigade of Guards.

At the beginning of Second World War, Kitty worked for left-wing newspapers such as the People's Independent. In 1939 Elizabeth Wintringham and her son Oliver left London to live in Derbyshire. Oliver attended Abbotsholme School. On 12th February 1940 Elizabeth petitioned for divorce.

Their friends during this period included Storm Jameson, Naomi Mitchison, Stephen Swingler and Pearl Binder. However, Anne Swingler pointed out: "She (Kitty) certainly didn't like pretty young girls around. She was thin, with wild dark hair and an awkward manner. I thought she was scatty, an endless talker, but bossy too. She was very possessive of Tom. People avoided her." Anne liked Tom a great deal: "He spoke with such authority but he was gentle and charming too. Quite a lady's man! And he thrived on women's company."

On 20th May 1940 Wintringham became the Military Correspondent of the Daily Mirror. He continued to write for other publications. One article published in the Picture Post on 15th June that gave practical instructions for a people's war to resist invasion was bought by the War Office which printed off 100,000 copies and distributed them to Home Guard units.

The War Office became concerned about the activities of the Osterley Park Training School. The Inspector's Directorate of the Home Guard reported in July 1940: "While approving of the school in principle, the London District Assistant Commander did not think the Instructors were of a suitable type because of communistic tendencies. On 10th September General Pownall informed the Inspector's Directorate that "the school at Osterley was gradually being taken over by the War Office." In the spring of 1941 Wintringham was dismissed from his post as director of the training school.

On this day in 1943 Emanuel Celler pleads with Congress to allow more German Jews into America.

Mr. Speaker, nations have declared war on Germany, and their high-ranking officials have issued pious protestations against the Nazi massacre of Jewish victims, but not one of those countries thus far has said they would be willing to accept these refugees either permanently or as visitors, or any of the minority peoples trying to escape the Hitler prison and slaughterhouse.

Goebbels says: "The United Nations won't take any Jews. We don't want them. Let's kill them." And so he and Hitler are making Europe Judenrein.

Without any change in the immigration statutes we could receive a reasonable number of those who are fortunate enough to escape the Nazi hellhole, receive them as visitors, the immigration quotas notwithstanding. They could be placed in camps or cantonments and held there in such havens until after the war. Private charitable agencies would be willing to pay the entire cost thereof. They would be no expense to the government whatsoever. These agencies would even pay for transportation by ships to and from this country.

We house and maintain Nazi prisoners, many of them undoubtedly responsible for Nazi atrocities. We should do no less for the victims of the rage of the Huns.

On this day in 1971 blacklisted director Herbert Biberman died of bone cancer. Herbert Biberman was born in Philadelphia on 4th March, 1900. Educated at the University of Pennsylvania he spent several years in Europe before joining the family textile business.

In 1928 Biberman joined the Theater Guild as an assistant stage manager and the following year directed the Soviet play, Red Rust. After marrying the actress Gale Sondergaard in 1930, Biberman directed three more plays: Roar China, Green Grow the Lilacs and Miracle at Verdun.

Biberman moved to Hollywood and directed One Way Ticket (1935), Meet Nero Wolfe (1936) and The Master Race (1944). He also wrote Together Again (1944) and New Orleans (1947).

After the Second World War the House of Un-American Activities Committee began an investigation into the Hollywood Motion Picture Industry. In September 1947, the HUAC interviewed 41 people who were working in Hollywood. These people attended voluntarily and became known as "friendly witnesses". During their interviews they named several people who they accused of holding left-wing views.

Biberman appeared before the HUAC on 29th October, 1947, but like, Alvah Bessie, Lester Cole, Albert Maltz, Adrian Scott, Dalton Trumbo, Edward Dmytryk, Ring Lardner Jr., Samuel Ornitz and John Howard Lawson, he refused to answer any questions. Known as the Hollywood Ten, they claimed that the 1st Amendment of the United States Constitution gave them the right to do this. The House of Un-American Activities Committee and the courts during appeals disagreed and all were found guilty of contempt of Congress and Biberman was sentenced to six months in Texarkana Federal Correctional Institution and fined $1,000.

Blacklisted by the Hollywood studios, Biberman was forced to finance his own work. In 1954 he worked with Michael Wilson, Adrian Scott and Paul Jarrico on Salt of the Earth (1954), a film about a mining strike in New Mexico. Although the film earned critical acclaim in Europe, winning awards in France and Czechoslovakia, it was not allowed to be shown in the United States until 1965.

After the blacklist was lifted, Biberman was able to write the screenplay and direct the movie, Slaves (1969), an adaptation of Uncle Tom's Cabin.

On this day in 1972, the writer, Guy Chapman dies. Chapman, the son of a wealthy barrister, G. W. Chapman, was born in London in on 11th September 1889. He was educated at Westminster School, Christ Church College (1908-11) and the London School of Economics before becoming a lawyer in 1914. Later that year Chapman married Doris May Bennett at Kensington Register Office.

On the outbreak of the First World War, Chapman joined the Royal Fusiliers as a junior officer. He later wrote: "I was loath to go. I had no romantic illusions. I was not eager, or even resigned to self-sacrifice, and my heart gave back no answering throb to thought of England. In fact, I was very much afraid; and again, afraid of being afraid, anxious lest I show it." Chapman was not impressed by the quality of his training: "The ten months' training, which the battalion went through before it reached France, was therefore a compound of enthusiasm and empiricism on the part of the junior subalterns and the other ranks. We listened hopefully to the lectures of general officers who seemed happier talking of Jubulpore than of Ypres. We pondered the jargon of experts, each convinced that his peculiar weapon, machine-gun, rifle, bayonet, or bomb, was the one designed to bring the war to a satisfactory conclusion."

Chapman arrived on the Western Front in August 1915. He was appalled by the state of the trenches. "The trench was not a trench at all. The bottom may have been two feet below ground level. An enormous breastwork rose in the darkness some ten or more feet high. All about us there was an air of bustle. Men were lifting filled sandbags on to the parapet and beating them into the wall with shovels. Bullets cracked in the darkness. Every now and then a figure would appear on the skyline and drop skillfully on the firestep."

Chapman also found the mud a serious problem: "Rain had made our bare trenches a quag, and earth, unsupported by revetments, was beginning to slide to the bottom. We hailed the first frost which momentarily arrested our ruin. Saps filled up and had to be abandoned. The cookhouse disappeared. Dugouts filled up and collapsed. The few duckboards floated away, uncovering sump-pits into which the uncharted wanderer fell, his oaths stifled by a brownish stinking fluid."

In the summer of 1916 Chapman took part in the Battle of the Somme. He found that the morale of his men suffered after the offensive failed to break-through the German front-line: "The men, though docile, willing, and biddable, were tired beyond hope. They lived from hand to mouth, expecting nothing, and so disappointed nowhere. They were no longer decoyed by the vociferous patriotism of the newspapers. They no longer believed in the purity of politicians or the sacrifices of profiteers. They were fed up with England as they were with France and Belgium. The best they could count on was a blighty, a little breathing space to stretch their legs and fill their lungs with sweet air."

After surviving the Battle of Arras in 1917, Chapman was badly affected by a mustard-gas attack. "The Boche dropped half a dozen mustard-gas shells round headquarters. I had heard them, but since I had smelt nothing had neglected to put on my gas-mask. Now my eyes had begun to run, and as soon as I opened them fountains of water gushed down my cheeks. Doctor Toulson washed them and washed them. It was no use. The flood continued." After treatment he returned to the Western Front and was still there when the Armistice was signed in 1918.

Guy Chapman was demobilised in February 1920, with the rank of major. After divorcing his wife he got a job as manager for a new London branch of an Irish publishing firm, Chapman and Dodd, in Denmark Street, Soho. In January 1924 the writer, Storm Jameson, came to the office. Chapman later commented: "She was wearing a heavy coat over a faded pink knitted dress, and a hat which did not suit her, and she smiled at me. She was rather lovely, with long cool grubby fingers, and she held herself badly: she made me think of a well-bred foal, unbroken and enchantingly awkward. Something she said at that first meeting, I forget what, made me laugh with pure pleasure."

They soon began a relationship. The couple married on 1st February 1926. Later she wrote: "We went to places, obscure ruined monasteries, small provincial art galleries, the house in which a dead philosopher spent his life, salt marshes, trout streams, some turn in a rough nameless road which offered a view of a smiling valley and a line of hills, because, although he had not seen them, he knew they were there. He made all other company a little dull."

Chapman became a university lecturer and eventually became Professor of Modern History at the University of Leeds (1945-53). He published several books including an account of his wartime experiences, A Passionate Prodigality (1933). He also edited two important collections of prose from the war, Fifty Amazing Stories Of The Great War (1936) and Vain Glory (1937).

Other books by Guy Chapman include Culture and Survival (1940), Beckford (1952), The Dreyfus Trials (1955), The Third Republic of France (1962) and Why France Collapsed (1968).