On this day on 29th April

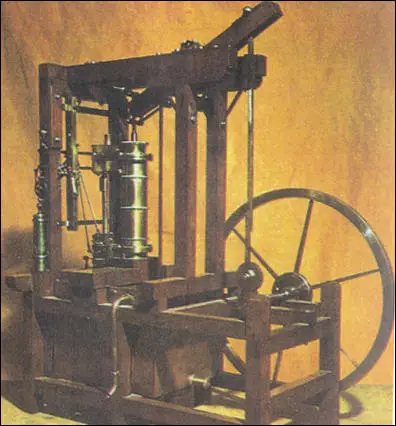

On this day in 1765 James Watt wrote to James Lind about his new invention. "I have now almost a certainty of the facturum of the fire-engine, having determined the following particulars: the quantity of steam produced; the ultimatum of the lever engine; the quantity of steam produced; the quantity of steam destroyed by the cold of its cylinder; the quantity destroyed in mine... mine ought to raise water to 44 feet with the same quantity of steam that there does to 32 (supposing my cylinder as thick as theirs). I can now make a cylinder of 2 feet diameter and 3 feet high only a 40th of an inch thick, and strong enough to resist the atmosphere... in short, I can think of nothing else but this machine."

James Watt built an instrument-maker's model but the next stage involved producing a massive working engine made of brick and iron. Watt had no money for large-scale models and so he had to seek a partner with capital. Watt's friend, Joseph Black, introduced him to John Roebuck, the owner of Carron Ironworks near Falkirk in Scotland. He also owned nearby coal mines to provide fuel for his ironworks.

Roebuck agreed and the two men went into partnership. Roebuck held two-thirds of the original patent (9th January 1769) in return for discharging some of Watt's debts. James Patrick Muirhead, the author of The Life of James Watt (1854) claims that Roebuck's made every effort to get Watt's machine into production as he was "ardent and sanguine in the pursuit of his undertakings".

In March 1773 Roebuck became bankrupt. At the time he owed Matthew Boulton over £1,200. Boulton knew about Watt's research and wrote to him making an offer for Roebuck's share in the steam-engine. Roebuck refused but on 17th May, he changed his mind and accepted Boulton's terms. James Watt was also owed money by Roebuck, but as he had done a deal with his friend, he wrote a formal discharge "because I think the thousand pounds he (Boulton) he has paid more than the value of the property of the two thirds of the inventions."

Roger Osborne, the author of Iron, Steam and Money: The Making of the Industrial Revolution (2013) has argued: "The two men instantly knew they could work together. Perhaps Watt saw that Boulton was the necessary complement to his own gloomy character - an energetic optimist who would carry him through his difficulties - while Boulton surely recognised the seriousness of Watt's character.... Watt was delighted not just by the prospect of investment hut especially by Boulton's personal enthusiasm."

Boulton pointed out that before he would give Watt financial backing, he insisted that the 1769 patent, with only eight years to run, should be extended to twenty-five years. This meant petitioning the House of Commons. By 1775 the two men had their patent which gave them "the sole use and property of certain steam-engines of his invention, throughout the majesty's dominions." This prevented others from making steam-engines which contained improvements of their own.

Under the terms of the partnership James Watt assigned two-thirds of both property and the patent to Boulton. In return Boulton undertook to pay the expenses already incurred, to meet the costs of experiments, and to pay for materials and wages. The profits were to be divided in proportion to their shares. "It would be incorrect to stereotype Boulton as the entrepreneur and Watt as the inventor, for Boulton made many suggestions for improvements to the engine and Watt also had a good head for business. But there is no doubt that Boulton's flair for marketing was significant for the early success of the business."

For the next eleven years Boulton's factory produced and sold Watt's steam-engines. These machines were mainly sold to colliery owners who used them to pump water from their mines. Watt's machine was very popular because it was four times more powerful than those that had been based on the Thomas Newcomen design.

One of their machines was installed at Whitbread's Brewery in London in 1775 to grind malt and raise the liquor, taking the place of a huge wheel which needed six horses at a time to turn it. The company was very pleased with the economic benefits of Watt's steam engine that had cost them only £1,000.

On this day in 1818 Alexander II, the eldest son of Tsar Nicholas I, was born in Moscow. Educated by private tutors, he also had to endure rigorous military training that permanently damaged his health.

In 1841 he married Marie Alexandrovna, the daughter of the Grand Duke of Hesse-Darmstadt. Alexander became Tsar of Russia on the death of his father in 1855. At the time Russia was involved in the Crimean War and in 1856 signed the Treaty of Paris that brought the conflict to an end.

The Crimean War made Alexander realize that Russia was no longer a great military power. His advisers argued that Russia's serf-based economy could no longer compete with industrialized nations such as Britain and France.

Alexander now began to consider the possibility of bringing an end to serfdom in Russia. The nobility objected to this move but as Alexander told a group of Moscow nobles: "It is better to abolish serfdom from above than to wait for the time when it will begin to abolish itself from below".

In 1861 Alexander issued his Emancipation Manifesto that proposed 17 legislative acts that would free the serfs in Russia. Alexander announced that personal serfdom would be abolished and all peasants would be able to buy land from their landlords. The State would advance the the money to the landlords and would recover it from the peasants in 49 annual sums known as redemption payments.

Alexander also introduced other reforms and in 1864 he allowed each district to set up a Zemstvo. These were local councils with powers to provide roads, schools and medical services. However, the right to elect members was restricted to the wealthy.

Other reforms introduced by Alexander included improved municipal government (1870) and universal military training (1874). He also encouraged the expansion of industry and the railway network.

Alexander's reforms did not satisfy liberals and radicals who wanted a parliamentary democracy and the freedom of expression that was enjoyed in the United States and most other European states. The reforms in agricultural also disappointed the peasants. In some regions it took peasants nearly 20 years to obtain their land. Many were forced to pay more than the land was worth and others were given inadequate amounts for their needs.

In 1876 a group of reformers established Land and Liberty. As it was illegal to criticize the Russian government, the group had to hold its meetings in secret. Influenced by the ideas of Mikhail Bakunin, the group published literature demanding that Russia's land should be handed over to the peasants.

Some reformers favoured a policy of terrorism to obtain reform and on 14th April, 1879, Alexander Soloviev, a former schoolteacher, tried to kill Alexander. His attempt failed and he was executed the following month. So also were sixteen other men suspected of terrorism.

The government responded to the assassination attempt by appointing six military governor-generals that imposed a rigorous system of censorship on Russia. All radical books were banned and known reformers were arrested and imprisoned.

In October, 1879, the Land and Liberty split into two factions. The majority of members, who favoured a policy of terrorism, established the People's Will. Soon afterwards the group decided to assassinate Alexander. The following month Andrei Zhelyabov and Sophia Perovskaya used nitroglycerine to destroy the Tsar train. However, the terrorist miscalculated and it destroyed another train instead. An attempt the blow up the Kamenny Bridge in St. Petersburg as the Tsar was passing over it was also unsuccessful.

The next attempt on Alexander's life involved a carpenter, Stefan Khalturin, who had managed to find work in the Winter Palace. Allowed to sleep on the premises, each day he brought packets of dynamite into his room and concealed it in his bedding.

On 17th February, 1880, Khalturin constructed a mine in the basement of the building under the dinning-room. The mine went off at half-past six at the time that the People's Will had calculated Alexander would be having his dinner. However, his main guest, Prince Alexander of Battenburg, had arrived late and dinner was delayed and the dinning-room was empty. Alexander was unharmed but sixty-seven people were killed or badly wounded by the explosion.

The People's Will contacted the Russian government and claimed they would call off the terror campaign if the Russian people were granted a constitution that provided free elections and an end to censorship. On 25th February, 1880, Alexander announced that he was considering granting the Russian people a constitution. To show his good will a number of political prisoners were released from prison. Loris Melikof, the Minister of the Interior, was given the task of devising a constitution that would satisfy the reformers but at the same time preserve the powers of the autocracy.

At the same time the Russian Police Department established a special section that dealt with internal security. This unit eventually became known as the Okhrana. Under the control of Loris Melikof, the Minister of the Interior, undercover agents began joining political organizations that were campaigning for social reform.

In January, 1881, Loris Melikof presented his plans to Alexander II. They included an expansion of the powers of the Zemstvo. Under his plan, each zemstov would also have the power to send delegates to a national assembly called the Gosudarstvenny Soviet that would have the power to initiate legislation. Alexander was concerned that the plan would give too much power to the national assembly and appointed a committee to look at the scheme in more detail.

The People's Will became increasingly angry at the failure of the Russian government to announce details of the new constitution. They therefore began to make plans for another assassination attempt. Those involved in the plot included Sophia Perovskaya, Andrei Zhelyabov, Gesia Gelfman, Nikolai Sablin, Ignatei Grinevitski, Nikolai Kibalchich, Nikolai Rysakov and Timofei Mikhailov.

In February, 1881, the Okhrana discovered that their was a plot led by Andrei Zhelyabov to kill Alexander. Zhelyabov was arrested but refused to provide any information on the conspiracy. He confidently told the police that nothing they could do would save the life of the Tsar.

On 13th March, 1881, Alexander was travelling in a closed carriage, from Michaelovsky Palace to the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg. An armed Cossack sat with the coach-driver and another six Cossacks followed on horseback. Behind them came a group of police officers in sledges.

All along the route he was watched by members of the People's Will. On a street corner near the Catherine Canal Sophia Perovskaya gave the signal to Nikolai Rysakov and Timofei Mikhailov to throw their bombs at the Tsar's carriage. The bombs missed the carriage and instead landed amongst the Cossacks. The Tsar was unhurt but insisted on getting out of the carriage to check the condition of the injured men. While he was standing with the wounded Cossacks another terrorist, Ignatei Grinevitski, threw his bomb. Alexander was killed instantly and the explosion was so great that Grinevitski also died from the bomb blast.

Of the other conspirators, Nikolai Sablin committed suicide before he could be arrested and Gesia Gelfman died in prison. Sophia Perovskaya, Andrei Zhelyabov, Nikolai Kibalchich, Nikolai Rysakov and Timofei Mikhailov were hanged on 3rd April, 1881.

On this day in 1832 the Poor Man's Guardian publishes article on parliamentary reform. "To talk of representation, in any shape, being of any use to the people is sheer nonsense, unless the people have a House of working men, and represent themselves. Those who make the laws now, and are intended, by the reform bill, to make them in future all live by profits of some sort or another. They will, therefore, no matter who elect them,or how often they are elected, always make the laws to raise profits and keep down the price of labour."

Henry Hetherington worked for Richard Carlile as a shopman before he began publishing the daily paper Penny Papers for the People in 1830. In the first edition published on 1st October, 1830, Hetherington explain his motives for publishing this paper: "It is the cause of the rabble we advocate, the poor, the suffering, the industrious, the productive classes. We will teach this rabble their power - we will teach them that they are your master, instead of being your slaves."

In July 1831 Hetherington changed the name of his paper to the Poor Man's Guardian. Hetherington's refused to pay the 4d. stamp duty on each paper sold. On the front page, where the red spot of the stamp duty should have been, Hetherington printed the slogan "Knowledge is Power". Underneath were the words, "Published in Defiance of the Law, to try the Power of Right against Might".

The Poor Man's Guardian was closely associated with the National Union of the Working Classes, an organisation formed earlier that year by Hetherington and William Lovett to campaign for universal suffrage and trade union rights. Hetherington gave extensive coverage to the struggle over the 1832 Reform Act and was deeply disappointed by the refusal of Parliament to give the vote to working men.

Henry Hetherington toured Britain giving speeches on parliamentary reform and recruiting agents to sell the Poor Man's Guardian. By 1833 circulation had reached 22,000, with two-thirds of the copies being sold in the provinces. In a three year period, twenty-five of these forty agents went to prison for selling an unstamped newspaper. One of those was arrested was George Julian Harney, who was imprisoned three times for selling the Poor Man's Guardian. Later Harney was to become the editor of the very successful Chartist newspaper, The Northern Star.

Hetherington was also imprisoned for two periods of six months and in November 1832, he was replaced as editor by James Bronterre O'Brien. The new editor had been influenced by European socialist writers such as Gracchus Babeuf and began publishing translations of their work in the Poor Man's Guardian. O'Brien argued that workers in other countries were also involved in a struggle for universal suffrage. In October 1834 he wrote: "The history of mankind shows that from the beginning of the world, the rich of all countries have been in a permanent state of conspiracy to keep down the poor of all countries, and for this plain reason - because the poverty of the poor man is essential to the riches of the rich man. The desire of one man to live on the fruits of another's labour is the original sin of the world."

Although the Poor Man's Guardian gave its support to the trade union movement it constantly argued that the real struggle was for universal suffrage. As it pointed out on many occasions, if working men were not represented in the House of Commons, gains made by the trade unions could always be undermined by legislation passed by Parliament.

The campaign for an untaxed press obtained a boast in June 1834 when it was ruled that the Poor Man's Guardian was not an illegal publication. The newspaper reported: "After all the badgerings of the last three years - after all the fines and incarcerations - after all the spying and blood-money, the Poor Man's Guardian was pronounced, on Tuesday by the Court of Exchequer (and by a Special Jury too) to be a perfectly legal publication." As a result of this court ruling, Henry Hetherington invested in a new printing press, the Napier double-cylinder, a machine capable of printing 2,500 copies an hour.

In 1835 the two leading unstamped radical newspapers, the Poor Man's Guardian, and The Police Gazette, were selling more copies in a day than The Times sold all week. It was estimated at the time that the circulation of leading six unstamped newspapers had now reached 200,000.

The authorities continued to try and stop the newspaper being sold. In 1835 Joseph Swann was sentenced to four and a half years for selling The Poor Man's Guardian. During the trial he explained his actions. Well, sir, I have been out of employment for some time; neither can I obtain work; my family are all starving... And for another reason, the weightiest of all; I sell them for the good of my fellow countrymen; to let them see how they are misrepresented in parliament... I wish every man to read those publications."

In 1835 the offices of the newspaper were raided. Hetherington's stock and equipment, including his new Napier printing machine, was seized and destroyed. For a while Henry Hetherington printed the Poor Man's Guardian on borrowed equipment but in December, 1835, he decided to cease publication.

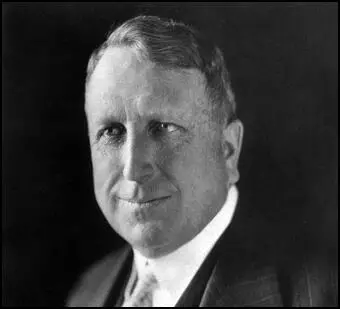

On this day in 1863 William Randolph Hearst, the son of George Hearst, a newspaper proprietor, was born in San Francisco. After studying at Harvard University (1882-85) he took over the San Francisco Examiner from his father in 1887.

Inspired by the journalism of Joseph Pulitzer, Hearst turned the newspaper into a combination of reformist investigative reporting and lurid sensationalism. He soon developed a reputation for employing the best journalists available. This included Ambrose Bierce, Stephen Crane, Mark Twain, Richard Harding Davis and Jack London.

In 1895 Hearst purchased the New York Journal. He was now in competition with Pulitzer's New York World. This included recruiting the popular cartoonist, Richard F. Outcault from Joseph Pulitzer. Hearst also reduced the price of the New York Journal to one cent and included colour magazine sections. He also persuaded Frederick Opper, another of Pulitzer's cartoonists, to join his team.

Pulitzer's New York World and Hearst's New York Journal became involved in a circulation war, and their use of promotional schemes and sensational stories became known as yellow journalism. However, he received praise from the radical journalist, Lincoln Steffens: "Hearst, in journalism, was like a reformer in politics; he was an innovator who was crashing into the business, upsetting the settled order of things, and he was not doing it as we would have done it. He was doing it his way. I thought that Hearst was a great man, able, self-dependent, self-educated (though he had been to Harvard) and clear-headed; he had no moral illusions; he saw straight as far as he saw, and he saw pretty far, further than I did then; and, studious of the methods which he adopted after experimentation, he was driving toward his unannounced purpose: to establish some measure of democracy, with patient but ruthless force."

Over the next few years Hearst became the owner of 28 newspapers and magazines, including the Los Angeles Examiner, the Boston American, the Atlanta Georgian, the Chicago Examiner, the Detroit Times, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Cosmopolitan and the Washington Herald. He used his newspapers and magazines to campaign for an aggressive foreign policy. As a result of distorted and exaggerated reporting, Hearst was blamed for the war between the United States and Spain (1897-98).

Hearst was a member of the United States House of Representatives (1903-07) However, he was defeated for mayor (1905 and 1909) and the post of governor of New York (1906). An opponent of the British Empire, Hearst opposed United States involvement in the First World War and attacked the formation of the League of Nations.

In the 1920s Hearst built a castle on a 240,000 acre ranch at San Simeon, California. At his peak he owned 28 major newspapers and 18 magazines, along with several radio stations and movie companies.

Hearst became more conservative in his sixties and supported Herbert Hoover in the 1928 Presidential Election. However, the Great Depression had a serious impact on his business empire and in 1932 all his newspapers recommended voting for Franklin D. Roosevelt. He welcomed Roosevelt's New Deal but objected to the legislation that helped trade unions such as the National Recovery Administration and National Labor Act and began describing Roosevelt as a "communist".

As Roosevelt was a popular president this resulted in a decline in sales of his newspapers and by 1940 he had lost personal control of his vast communications empire. Hearst also started praising Adolf Hitler and was a supporter of the America First Committee.

In 1940 Orson Welles moved to Hollywood and made Citizen Kane. Based on the life of William Randolph Hearst, it is considered one of the best movies in the history of the cinema. Hearst attempted to get the movie banned and although he failed to do this he did make it difficult for the film to be exhibited.

William Randolph Hearst died on 14th August 1951.

On this day in 1880 Catherine Marshall, the daughter of Francis E. Marshall (1847–1922), a mathematics master at Harrow School, was born on 29th April 1880 at Harrow-on-the-Hill. She was educated privately before attending St Leonards School (1896-99).

Catherine later recalled that: "Ever since I was old enough to think about politics at all I have been a Liberal." As a young woman she read the work of John Stuart Mill: "I was profoundly impressed by them." Her biographer, Jo Vellacott, has pointed out that she "left earlier than she might have chosen, although she was nineteen years old... her mother was still unwell and Catherine was needed at home."

Her parents were supporters of the Liberal Party and she became secretary of Women's Liberal Association in Harrow. In 1904 she became a member of the London Society for Women's Suffrage. However, it was another four years before she became an active supporter of women's rights. After the retirement of her father the family moved to Hawse End, on the edge of Derwentwater. Soon afterwards she became a Poor Law guardian.

In May 1908 Catherine and her mother joined the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) and established a branch in Keswick. Catherine reported: "A committee was formed, rules drawn up, and active propaganda work started at once. It was unanimously decided that our object should be votes for women on the same terms as for men, and that the Association should be a strictly non-party organization; we also pledged ourselves to peaceful and constitutional methods only. Our work was to consist of spreading the principles of Women's Suffrage by means of meetings, of Ietters to the press, of distributing literature on the subject.... The audience at these meetings averaged between 50 and 100 in numbers; in every instance a resolution in favour of votes for women on the same terms as for men was enthusiastically carried."

Catherine Marshall soon showed that she had all the necessary skills to become an excellent organiser. Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999) has pointed out: "Catherine Marshall's initiative of setting up a stall in Keswick marketplace from which to sell suffrage literature was one that was soon emulated by other NUWSS societies. She was full of energy in campaigning across Westmoreland and Cumberland, organizing there a model campaign for the general election in January 1910."

Marshall pointed out that influencing the local media was vitally important: "It does mean a great deal of work... I have been doing it myself, though with nothing like thoroughness, in connection with twenty local papers, and it has made very great demands on my time. But the results have more than repaid the cost. Of these twenty papers not one is now hostile; not one ever misrepresents us (that alone is an immense gain); most of them give excellent - almost verbatim - reports of all our meetings, and several support us actively in their editorial columns.... Some of the editors needed educating, but one of our chief tasks is to educate public opinion, and the local papers have an important influence on public opinion in country districts. Educate their editors, and you are educating public opinion at its fountain-head. The difference which a favourable local press makes to the success of' our propaganda work is simply incalculable."

During the January 1910 General Election the NUWSS organised the signing petitions in 290 constituencies. They managed to obtain 280,000 signatures and this was presented to the House of Commons in March 1910. With the support of 36 MPs a new suffrage bill was discussed in Parliament. The WSPU suspended all militant activities and on 23rd July they joined forces with the NUWSS to hold a grand rally in London. When the House of Commons refused to pass the new suffrage bill, the WSPU broke its truce on what became known as Black Friday on 18th November, 1910, when its members clashed with the police in Parliament Square.

Although the NUWSS campaign had ended in failure, the extra publicity it had received, increased membership from 13,429 in 1909 to 21,571 to 1910. It now had 207 societies and its income had reached £14,000. It was decided to restructure the NUWSS into federations. By 1911 the NUWSS now had 16 federations and 26,000 members. The NUWSS now had enough funds to appoint Catherine Marshall and Kathleen Courtney to full-time posts at national headquarters. They joined Helena Swanwick and Maude Royden as the group that represented the new generation in the NUWSS.

According to her biographer, Jo Vellacott: "Tall, well dressed, well informed, and dynamic, Marshall could hold the attention of an outdoor audience of miners, and was also a familiar figure to members of parliament, as she pressed the converted for action, cultivated sympathizers, and shamed backsliders." In June 1911 she attended the International Women's Suffrage Alliance meetings in Stockholm.

Herbert Asquith and his Liberal Party government still refused to support legislation. At its annual party conference in January 1912, the Labour Party passed a resolution committing itself to supporting women's suffrage. This was reflected in the fact that all Labour MPs voted for the measure at a debate in the House of Commons on 28th March. Soon afterwards Henry N. Brailsford and Kathleen Courtney, entered negotiations with the Labour Party as representatives of NUWSS.

In April 1912, the NUWSS announced that it intended to support Labour Party candidates in parliamentary by-elections. The NUWSS established an Election Fighting Fund (EFF) to support these Labour candidates. The EFF Committee, which administered the fund, included Catherine Marshall, Margaret Ashton, Henry N. Brailsford, Kathleen Courtney, Muriel de la Warr, Millicent Fawcett, Isabella Ford, Laurence Housman, Margory Lees and Ethel Annakin Snowden. The NUWSS also employed organizers such as Ada Nield Chew and Selina Cooper, who were active members of the Labour Party.

Catherine Marshall played an important role in trying to persuade senior figures in the Liberal Party to favour legislation on women's suffrage. She told John Simon: "I left school I started working for the Liberal Party almost as hard as I am working for women's suffrage now. It has been the greatest disillusionment of my life to find how little these principles really count with the majority of Liberal men. They seem to regard them as catchwords to pad a leaflet or adorn a peroration, not as vital principles to be applied in their dealings with other human beings." Catherine also contacted David Lloyd George: "I often wish you were an unenfranchised woman instead of being Chancellor of the Exchequer! With what fire you would lead the women's movement, and insist that no legislation was more important than the right of those whom it concerned to have a say in it."

In July 1914 the NUWSS argued that Asquith's government should do everything possible to avoid a European war. Two days after the British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914, Millicent Fawcett declared that it was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Although the NUWSS supported the war effort, it did not follow the WSPU strategy of becoming involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces.

Despite pressure from members of the NUWSS, Fawcett refused to argue against the First World War. Her biographer, Ray Strachey, argued: "She stood like a rock in their path, opposing herself with all the great weight of her personal popularity and prestige to their use of the machinery and name of the union." At a Council meeting of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies held in February 1915, Fawcett attacked the peace efforts of people like Mary Sheepshanks. Fawcett argued that until the German armies had been driven out of France and Belgium: "I believe it is akin to treason to talk of peace."

After a stormy executive meeting in Buxton all the officers of the NUWSS (except the Treasurer) and ten members of the National Executive resigned over the decision not to support the Women's Peace Congress at the Hague. This included Catherine Marshall, Chrystal Macmillan, Kathleen Courtney, Margaret Ashton, Eleanor Rathbone and Maude Royden, the editor of the The Common Cause.

Kathleen Courtney wrote when she resigned: "I feel strongly that the most important thing at the present moment is to work, if possible on international lines for the right sort of peace settlement after the war. If I could have done this through the National Union, I need hardly say how infinitely I would have preferred it and for the sake of doing so I would gladly have sacrificed a good deal. But the Council made it quite clear that they did not wish the union to work in that way."

In April 1915, Aletta Jacobs, a suffragist in Holland, invited suffrage members all over the world to an International Congress of Women in the Hague. Some of the women who attended included Mary Sheepshanks, Jane Addams, Alice Hamilton, Grace Abbott, Emily Bach, Lida Gustava Heymann, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Kathleen Courtney, Emily Hobhouse, Chrystal Macmillan, Rosika Schwimmer. At the conference the women formed the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WIL). Although the government blocked Marshall and other British women from travelling to the Hague, she immediately joined this organisation.

Soon after the outbreak of the First World War, two pacifists, Clifford Allen and Fenner Brockway, formed the No-Conscription Fellowship (NCF), an organisation that encouraged men to refuse war service. The NCF required its members to "refuse from conscientious motives to bear arms because they consider human life to be sacred." As Martin Ceadel, the author of Pacifism in Britain 1914-1945 (1980) has pointed out: "Though limiting itself to campaigning against conscription, the N.C.F.'s basis was explicitly pacifist rather than merely voluntarist.... In particular, it proved an efficient information and welfare service for all objectors; although its unresolved internal division over whether its function was to ensure respect for the pacifist conscience or to combat conscription by any means"

The NCF received support from public figures such as Catherine Marshall, Bertrand Russell, Philip Snowden, Bruce Glasier, Robert Smillie, C. H. Norman, C. E. M. Joad, William Mellor, Arthur Ponsonby, Guy Aldred, Alfred Salter, Duncan Grant, Wilfred Wellock, Herbert Morrison, Maude Royden, and Rev. John Clifford. Other members included Cyril Joad, Eva Gore-Booth, Esther Roper, Alfred Mason, Winnie Mason, Alice Wheeldon, William Wheeldon, John S. Clarke, Arthur McManus, Hettie Wheeldon, Storm Jameson, Ada Salter, Duncan Grant and Max Plowman.

Catherine Marshall fell in love with Clifford Allen, the chairman of the No-Conscription Fellowship, who was imprisoned in 1916. According to Jo Vellacott "Marshall suffered deeply when he was imprisoned; he was physically frail, and his health deteriorated rapidly in prison. By mid-1917, Catherine Marshall was compulsively driving herself towards breakdown, and Allen's health was further threatened by his intention of embarking on a hunger and work strike in prison. By the end of the year, Marshall had collapsed and Allen was released seriously ill. When both were convalescent they spent several months together in what seems to have been a trial marriage; Marshall was devastated when the relationship ended."

During the early years of the League of Nations, Marshall was often in Geneva, at the headquarters of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. In the 1930s she was involved in helping refugees escaping from Nazi Germany. Catherine Marshall remained active in the Labour Party.

Catherine Marshall died in the New End Hospital, Hampstead, on 22nd March 1961 after a fall at her home.

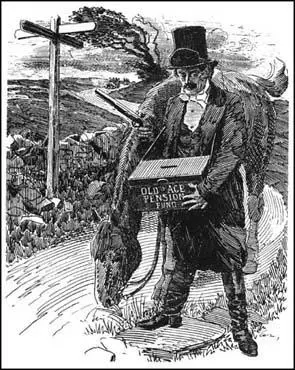

On this day in 1909 David Lloyd George makes People's Budget speech. "This is a war Budget. It is for raising money to wage implacable warfare against poverty and squalidness. I cannot help hoping and believing that before this generation has passed away, we shall have advanced a great step towards that good time, when poverty, and the wretchedness and human degradation which always follows in its camp, will be as remote to the people of this country as the wolves which once infested its forests."

Lloyd George had been a long opponent of the Poor Law in Britain. He was determined to take action that in his words would "lift the shadow of the workhouse from the homes of the poor". He believed the best way of doing this was to guarantee an income to people who were to old to work. Based on the ideas of Tom Paine that first appeared in his book Rights of Man, Lloyd George's proposed the introduction of old age pensions.

To pay for these pensions Lloyd George had to raise government revenues by an additional £16 million a year. In 1909 Lloyd George announced what became known as the People's Budget. This included increases in taxation. Whereas people on lower incomes were to pay 9d. in the pound, those on annual incomes of over £3,000 had to pay 1s. 2d. in the pound. Lloyd George also introduced a new super-tax of 6d. in the pound for those earning £5,000 a year. Other measures included an increase in death duties on the estates of the rich and heavy taxes on profits gained from the ownership and sale of property. Other innovations in Lloyd George's budget included labour exchanges and a children's allowance on income tax.

David Lloyd George had based his ideas on the reforms introduced by Otto von Bismarck in the 1880s. As The Contemporary Review reported: "English progressives have decided to take a leaf out of the book of Bismarck who dealt the heaviest blow against German socialism not by laws of oppression... but by the great system of state insurance which now safeguards the German workmen at almost every point of his industrial career."

Archibald Primrose, Lord Rosebery, the former Liberal Party leader, stated that: "The Budget, was not a Budget, but a revolution: a social and political revolution of the first magnitude... To say this is not to judge it, still less to condemn it, for there have been several beneficent revolutions." However, he opposed the Budget because it was "pure socialism... and the end of all, the negation of faith, of family, of property, of Monarchy, of Empire."

Ramsay MacDonald argued that the Labour Party should fully support the budget. "Mr. Lloyd George's Budget, classified property into individual and social, incomes into earned and unearned, and followers more closely the theoretical contentions of Socialism and sound economics than any previous Budget has done." MacDonald went on to argue that the House of Lords should not attempt to block this measure. "The aristocracy... do not command the moral respect which tones down class hatreds, nor the intellectual respect which preserves a sense of equality under a regime of considerable social differences."

David Lloyd George admitted that he would never have got his proposals through the Cabinet without the strong support of Asquith. He told his brother: "Budgeting all day... the Cabinet was very divided... Prime Minister decided in my favour to my delight". He told a friend: "The Prime Minister has backed me up through thick and thin with splendid loyalty. I have the deepest respect for him and he has real sympathy for the ordinary and the poor."

It was now clear that the House of Lords would block the budget. H. H. Asquith asked the King to create a large number of Peers that would give the Liberals a majority. Edward VII refused and his private secretary, Francis Knollys, wrote to Asquith that "to create 570 new Peers, which I am told would be the number required... would practically be almost an impossibility, and if asked for would place the King in an awkward position".

On 30th November, 1909, the Peers rejected the Finance Bill by 350 votes to 75. Asquith had no option but to call a general election. In January 1910, the Liberals lost votes and was forced to rely on the support of the 42 Labour Party MPs to govern. Asquith increased his own majority in East Fife but he was prevented from delivering his acceptance speech by members of the Women Social & Political Union who were demanding "Votes for Women".

John Grigg, the author of The People's Champion (1978) argues that the reason why the "people failed to give a sweeping, massive endorsement to the People's Budget" was that the electorate in 1910 was "by no means representative of the whole British nation". He points out that "only 58 per cent of adult males had the vote, and it is a fair assumption that the remaining 42 per cent would, if enfranchised, have voted in very large numbers for Liberal or Labour candidates. In what was still a disproportionately middle-class electorate the fear of Socialism was strong, and many voters were susceptible to the argument that the Budget was a first installment of Socialism."

Some of his critics on the left of the party believed that Asquith had not mounted a more aggressive campaign against the House of Lords. It was argued that instead of threatening its power to veto legislation, he should have advocated making it a directly elected second chamber. Asquith felt this was a step to far and was more interested in a negotiated settlement. However, to Colin Clifford, this made Asquith look "weak and indecisive".

In a speech on 21st February, 1910, Asquith outlined his plans for reform: "Recent experience has disclosed serious difficulties due to recurring differences of strong opinion between the two branches of the Legislature. Proposals will be laid before you, with convenient speed, to define the relations between the Houses of Parliament, so as to secure the undivided authority of the House of Commons over finance and its predominance in legislation."

The Parliament Bill was introduced later that month. "Any measure passed three times by the House of Commons would be treated as if it had been passed by both Houses, and would receive the Royal Assent... The House of Lords was to be shorn absolutely of power to delay the passage of any measure certified by the Speaker of the House of Commons as a money bill, but was to retain the power to delay any other measure for a period of not less than two years."

Edward VII died in his sleep on 6th May 1910. His son, George V, now had the responsibility of dealing with this difficult constitutional question. David Lloyd George had a meeting with the new king and had an "exceedingly frank and satisfactory talk about the political crisis". He told his wife that he was not very intelligent as "there's not much in his head". However, he "expressed the desire to try his hand at conciliation... whether he will succeed is somewhat doubtful."

James Garvin, the editor of The Observer, argued it was time that the government reached a negotiated settlement with the House of Lords: "If King Edward upon his deathbed could have sent a last message to his people, he would have asked us to lay party passion aside, to sign a truce of God over his grave, to seek... some fair means of making a common effort for our common country... Let conference take place before conflict is irrevocably joined."

A Constitutional Conference was established with eight members, four cabinet ministers and four representatives from the Conservative Party. Over the next six months the men met on twenty-one occasions. However, they never came close to an agreement and the last meeting took place in November. George Barnes, the Labour Party MP, called for an immediate creation of left-wing peers. However, when a by-election at Walthamstow suggested a slight swing to the Liberals, Asquith decided to call another General Election.

David Lloyd George called on the British people to vote for a change in the parliamentary system: "How could anyone defend the Constitution in its present form? No country in the world would look at our system - no free country, I mean... France has a Senate, the United States has a Senate, the Colonies have Senates, but they are all chosen either directly or indirectly by the people."

The general election of December, 1910, produced a House of Commons which was almost identical to the one that had been elected in January. The Liberals won 272 seats and the Conservatives 271, but the Labour Party (42) and the Irish (a combined total of 84) ensured the government's survival as long as it proceeded with constitutional reform and Home Rule.

The Parliament Bill, which removed the peers' right to amend or defeat finance bills and reduced their powers from the defeat to the delay of other legislation, was introduced into the House of Commons on 21st February 1911. It completed its passage through the Commons on 15th May. A committee of the House of Lords then amended the bill out of all recognition.

According to Lucy Masterman, the wife of Charles Masterman, the Liberal MP for West Ham North, that David Lloyd George had a secret meeting with Arthur Balfour, the leader of the Conservative Party. Lloyd George had bluffed Balfour into believing that George V had agreed to create enough Liberal supporting peers to pass a new Parliament Bill.

Although a list of 249 candidates for ennoblement, including Thomas Hardy, Bertrand Russell, Gilbert Murray and J. M. Barrie, had been drawn up, they had not yet been presented to the King. After the meeting Balfour told Conservative peers that to prevent the Liberals having a permanent majority in the House of Lords, they must pass the bill. On 10th August 1911, the Parliament Act was passed by 131 votes to 114 in the Lords.

On this day in 1920 Ebenezer Howard established the company, Welwyn Garden City Limited, to plan and build the garden city. Louis de Soissons was appointed as architect and town planner and the first house was occupied just before Christmas 1920. To support it in its early years, Howard moved to 5 Guessens Road on the estate. In twelve years Welwyn Garden became a flourishing town of nearly 10,000 residents.

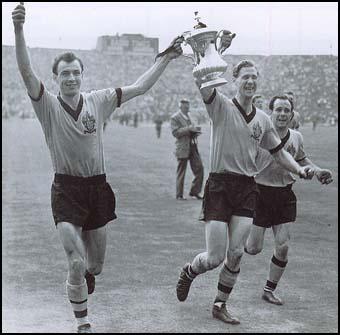

On this day in 1927 footballer Bill Slater was born in Clitheroe. A wing-half or inside-forward, he joined Blackpool as a 16 year old amateur in 1944 and made his debut in the first-team against Aston Villa on 10th September 1949. Later that season he scored after eleven seconds in a game against Stoke City. This remains as Blackpool's fastest-ever goal.

The Blackpool manager, Joe Smith, had built up a fine side that included Stanley Matthews, Hughie Kelly, Stan Mortensen, Bill Perry and Harry Johnson. In the 1950-51 season Blackpool finished in 3rd place in the First Division of the Football League.

Blackpool beat Stockport County (2-1), Mansfield Town (2-0), Fulham (1-0) and Birmingham City (2-1) to reach the final of the FA Cup against Newcastle United. The defences were in control in the first-half. The deadlock was broken in the 50th minute when Jackie Milburn collected a pass from George Robledo to fire home. Five minutes later, Ernie Taylor cleverly back-heeled the ball. As Milburn later recalled: "I struck it with all my might and from 28 yards it flew straight as an arrow into the back of the net." The game ended 2-0 and Slater had lost his first FA Cup final.

After finishing college, in December 1951 Slater moved to Brentford. However, he took up a post teaching at Birmingham University and in August 1952 he joined Wolves as a part-time professional. Managed by Stan Cullis, the team included Peter Broadbent, Johnny Hancocks, Sammy Smyth, Jesse Pye, Jimmy Dunn, Jimmy Mullen, Billy Crook, Ron Flowers, Roy Swinbourne, Roy Pritchard, Billy Wright, Bert Williams, Bill Shorthouse and Terry Springthorpe. That season Wolves finished in 3rd place and Slater scored three goals in 17 games.

Wolves won the First Division championship in the 1953-54 season with four more points than their nearest challenger, West Bromwich Albion. They scored an impressive 96 goals. The top goalscorers were Johnny Hancocks (25), Dennis Wilshaw (25), Roy Swinbourne (24), Jimmy Mullen (17) and Peter Broadbent (12). Slater, who was now playing in the wing-half position, played in 38 games.

Slater won his first international cap for England against Wales on 10th November 1954. England won the game 3-2. He held his place for the game against West Germany (3-1). The England team that season included Tom Finney, Stanley Matthews, Len Shackleton, Billy Wright, and Bert Williams.

In the 1954-55 season Wolves lost the services of Roy Swinbourne who was injured early in the season. Despite the goals of Johnny Hancocks (26) and Dennis Wilshaw (20), Wolves could only finish second to Chelsea. Slater scored 7 goals in 34 games that season.

Wolves won the League Championship in 1957-58 by 5 points from Preston North End. The club scored an amazing 103 league goals that season. Jimmy Murray was the club's leading scorer with 32 goals in 45 games.

Slater regained his place in the England team against Scotland on 19th April 1958. England won 4-0 and he held his place in games against Portugal (2-1), Yugoslavia (0-5), Soviet Union (1-1), Soviet Union (2-2), Brazil (0-0), Austria (2-2), Soviet Union (0-1), Soviet Union (5-0) and Scotland (1-1).

Wolves also won the title in the 1958-59 season with 28 wins in 42 games. Once again the forwards were in great form scoring 110 goals. This was seven more than Manchester United and 22 more than third placed Arsenal. Jimmy Murray was the club's leading scorer with 21 goals in 28 games. He was followed by Peter Broadbent (20), Norman Deeley (17) and Bobby Mason (13). Slater scored one goal in 27 games.

In the 1959-60 season the club was beaten into second placed by Burnley. Once again Wolves were the top scorers in the league with 106 goals. They did even better in the FA Cup that season with Norman Deeley scoring two of the goals in the 3-0 victory over Blackburn Rovers. That year the Football Writers' Association (FWA) named him as the Footballer of the Year.

In the 1960-61 season Wolves finished in 3rd place behind Tottenham Hotspur. The following season they finished 5th. After making 339 appearances and scoring 25 goals for Wolves he joined Brentford in July 1963. However, he only played in five games for his new club before retiring from professional football.

Slater was Director of Physical Education first at Liverpool University and then Birmingham University. In 1982 he was awarded the Order of the British Empire for his services to sport. In 1984 he became Director of National Services and in 1989 was elected as President of the British Gymnasts Association. In 1998 he was awarded the CBE.

Bill Slater died aged 91 on 18th December, 2018.

On this day in 1945 Dachau concentration camp is liberated by United States troops. Martha Gellhorn was with the United States troops that liberated Dachau in 1945. She later wrote about it in her book The Face of War (1959): "I have not talked about how it was the day the American Army arrived, though the prisoners told me. In their joy to be free, and longing to see their friends who had come at last, many prisoners rushed to the fence and died electrocuted. There were those who died cheering, because that effort of happiness was more than their bodies could endure. There were those who died because now they had food, and they ate before they could be stopped, and it killed them. I do not know words to describe the men who have survived this horror for years, three years, five years, ten years, and whose minds are as clear and unafraid as the day they entered. I was in Dachau when the German armies surrendered unconditionally to the Allies. We sat in that room, in that accursed cemetery prison, and no one had anything more to say. Still, Dachau seemed to me the most suitable place in Europe to hear the news of victory. For surely this war was made to abolish Dachau, and all the other places like Dachau, and everything that Dachau stood for, and to abolish it for ever."

On this day in 1968 women's suffrage campaigner Janie Allan died aged 100. Janie Allan, the daughter of Alexander Allan, the owner of the Allan Shipping Line, was born in Glasgow on 28th March, 1868. A socialist, Allan was one of the founders of the Glasgow and West of Scotland Association for Women's Suffrage in May 1902. Allan, one of its vice-presidents, agreed to represent the society on the committee of the National Union of Suffrage Societies in 1903.

On 11th December 1906 Janie Allan heard Helen Fraser speak about the recent formation of the Women Social & Political Union. The following year she joined the WSPU. In 1909 she gave £100 to the organisation. In November 1910 she gave £250 to the WSPU "War Chest". She also gave financial support to the Women's Freedom League.

In March 1912 the WSPU organised a new campaign that involved the large-scale smashing of shop-windows. Janie Allan agreed to join the campaign. May Billinghurst agreed to hide some of the stones underneath the rug covering her knees. According to Votes for Women: "From in front, behind, from every side it came - a hammering, crashing, splintering sound unheard in the annals of shopping... At the windows excited crowds collected, shouting, gesticulating. At the centre of each crowd stood a woman, pale, calm and silent." Allan was arrested and sentenced to four months' imprisonment. A petition protesting against her imprisonment was signed by 10,500 people from her native Glasgow.

In May she barricaded herself in her cell and it took three men, using crowbars, 45 minutes, to force an entrance. Janie Allan now went on hunger strike and was forcibly fed. She wrote to a friend after leaving prison: "I did not resist at all, but sat quite still as if it were a dentist chair, and yet the effect on my health was most disastrous - I am a very strong woman and absolutely sound in heart and lungs, but it was not till five months later, that I was able to take any exercise or begin to feel in my usual health again."

Janie Allan was a supporter of the Tax Resistance League and in 1913 she became vice-president of the National Political League. On 9th March 1914 it is claimed that Allan fired a blank from a pistol at a policeman who attempted to arrest Emmeline Pankhurst.

On 4th August, 1914, England declared war on Germany. Two days later the NUWSS announced that it was suspending all political activity until the war was over. The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort.

Emmeline Pankhurst announced that all militants had to "fight for their country as they fought for the vote." Ethel Smyth pointed out in her autobiography, Female Pipings for Eden (1933): "Mrs Pankhurst declared that it was now a question of Votes for Women, but of having any country left to vote in. The Suffrage ship was put out of commission for the duration of the war, and the militants began to tackle the common task."

Annie Kenney reported that orders came from Christabel Pankhurst: "The Militants, when the prisoners are released, will fight for their country as they have fought for the Vote." Kenney later wrote: "Mrs. Pankhurst, who was in Paris with Christabel, returned and started a recruiting campaign among the men in the country. This autocratic move was not understood or appreciated by many of our members. They were quite prepared to receive instructions about the Vote, but they were not going to be told what they were to do in a world war." Janie Allan followed these orders and during the First World War she helped provide funding for the Women's Hospital Corps.

After the passing of the Qualification of Women Act the NUWSS and WSPU disbanded. A new organisation called the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship was established. As well as advocating the same voting rights as men, the organisation also campaigned for equal pay, fairer divorce laws and an end to the discrimination against women in the professions.

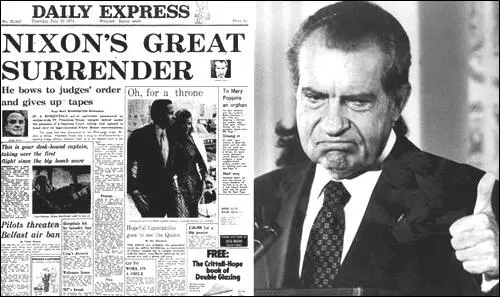

On this day in 1974 President Richard Nixon announces the release of edited transcripts of White House tape recordings relating to Watergate. On 20th April, 1973, John Dean issued a statement making it clear that he was unwilling to be a "scapegoat in the Watergate case". He told his lawyer: "I've been thinking that maybe I should go public with something. Maybe I should let them know I'm not going to take this lying down." When Dean testified on 25th June, 1973 before the Senate Committee investigating Watergate, he claimed that Richard Nixon participated in the cover-up. He also confirmed that Nixon had tape-recordings of meetings where these issues were discussed. (26)

Ben Bradlee points out that Bob Woodward found out that Alexander Butterfield was in charge of Nixon's "internal security" and suspected he had been responsible for arranging Nixon's secret recordings. He gave this information to "an investigator on the Ervin Committee". He passed this to Samuel Dash and Butterfield was interviewed on 13th July. Late that night, Woodward received a telephone call from the investigator: "We interviewed Butterfield. He told the whole story. Nixon bugged himself." Bradlee commented in his memoirs: "The death knell of Richard Nixon was tolling."

The Special Prosecutor now demanded access to these tape-recordings. At first Nixon refused. Carl Bernstein began calling sources at the White House: "Four of them said they had learned that the tapes were of poor quality, that there were gaps in some conversations. But they did not know whether these had been caused by erasures. Ron Ziegler told Bernstein there were no gaps or erasures in the tapes. However, on 21st November, Nixon's lawyers admitted that one of the tapes had a gap of over 18 minutes.

The Supreme Court ruled against Nixon and members of the Senate began calling for him to be impeached, he changed his mind. However, some tapes were missing while others contained important gaps. Under extreme pressure, Nixon supplied tape scripts of the missing tapes.Nixon's secretary, Rose Mary Woods, denied deliberately erasing the tape. It was now clear that Nixon had been involved in the cover-up and members of the Senate began to call for his impeachment.

On 9th August, 1974, Richard Nixon became the first President of the United States to resign from office. Nixon was granted a pardon but other members of his staff involved in helping in his deception were imprisoned. Nixon was granted a pardon but several members of his staff involved in the cover-up were imprisoned. This included: H. R. Haldeman, John Ehrlichman, Charles Colson, John Dean, John N. Mitchell, Jeb Magruder, Egil Krogh, Frederick LaRue, Robert Mardian and Dwight L. Chapin.