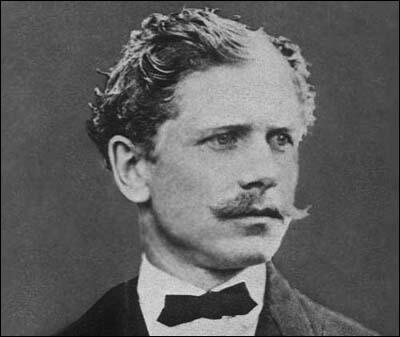

Ambrose Bierce

Ambrose Bierce was born in Meigs County, Ohio, on 24th June, 1842. He was a printer's apprentice but influenced by his uncle, Lucius Bierce, became a strong opponent of slavery.

On the outbreak of the Civil War Lucius Bierce organized and equipped two companies of marines. Bierce joined one of these on 19th April, 1861, and two months later became part of the invasion force led by George McClellan in West Virginia.

On 6th April, 1862, Albert S. Johnson and Pierre T. Beauregard and 55,000 members of the Confederate Army attacked Grant's army near Shiloh Church, in Hardin, Tennessee. Taken by surprise, Grant's army suffered heavy losses. Bierce was a member of the force led by General Don Carlos Buell that forced the Confederate to retreat. Bierce was deeply shocked by what he saw at Shiloh and after the war wrote several short stories based on this experience.

Bierce was promoted to the rank of second lieutenant in November, 1862. Two months later he fought at Murfreesboro where he saved the life of his commanding officer, Major Braden, by carrying his to safety and he had been seriously wounded in the fighting.

In February, 1862 Bierce was commissioned first lieutenant of Company C of the Ninth Indiana. He fought at Chickamuga (September, 1863) under General William Hazen. The sight of so many senior officers, including William Rosecrans, fleeing from the battlefield, deeply shocked Bierce. It is said that Bierce's idealism died that day and was replaced by cynicism. He later wrote that during the war he entered "a world of fools and rogues, blind with superstition, tormented with envy, consumed with vanity, selfish, false, cruel, cursed with illusions - frothing mad!"

Bierce served under General William Sherman during his Atlanta Campaign. At Resaca on 14th May, 1864, Bierce's close friend, Lieutenant Brayle was killed. Two weeks later his regiment suffered heavy losses when attacked by General Joseph Johnson at Pickett's Mill. Bierce was badly wounded at Kennesaw Mountain when he was shot in the head by a musket ball on 23rd June. While engaged in this duty, Lieutenant Bierce was shot in the head by a musket ball which caused a very dangerous and complicated wound, the ball remained within the head from which it was removed sometime afterwards.

General William Hazen reported: "After being treated in hospital he returned to the front-line on 30th September, 1864. The injury caused him long-term problems for the rest of his life. He later wrote: "for many years afterward, subject to fits of fainting, sometimes without assignable immediate cause, but mostly when suffering from exposure, excitement or excessive fatigue."

After the war Bierce went to California where he became a journalist working for the Overland Monthly. He travelled to England in 1872 and worked for humorous magazines in London such as Figaro and Fun. Bierce returned to the United States in 1875 and over the next twelve years he contributed to a wide variety of different journals.

In March, 1887, William Randolph Hearst, recruited Bierce to write a regular humorous article for his San Francisco Examiner. The articles were a great success and Hearst was soon paying Bierce $100 a week to retain his services.

Bierce held strong opinions and was especially critical of social reformers and liberal politicians. He advocated "a vigilant censorship of the press, a firm hand upon the church, keen supervision of public meetings and public amusements, command of the railroads, telegraph and all means of communications" in order to stop the growth of socialism.

In 1891 he published a book of short-stories, Tales of Soldiers and Civilians (later revised and republished as In the Midst of Life), about the American Civil War. Bierce followed this with Can Such Things Be? (1893), Fantastic Fables (1899) and Shapes of Clay (1903). In 1906 Bierce published The Cynic's Word Book (reissued in 1911 as The Devil's Dictionary).

As well as working for the San Francisco Examiner, Bierce contributed to journals such as Cosmopolitan, Everybody's, Hampton's Magazine and Pearson's. In 1895 he helped William Randolph Hearst with his campaign against the the railway magnate, Collis Huntington. It is argued that Bierce's articles helped to prevent the growth of Huntington's company, Southern Pacific.

In 1906 Bierce argued: "Nothing touches me more than poverty. I have been poor myself. I was one of those poor devils born to work as a peasant in the fields, but I found no difficulty getting out of it. I don't see that there is any remedy for the condition which consists in the rich being on top. They always will be. The reason that rich men are poor - this is not a rule without an exception - is that they are incapable. The rich become rich because they have brains."

Bierce spent spent from 1909 to 1912 editing his 12 volume Collected Works. In June 1913 Ambrose Bierce went to Mexico where he disappeared. It is not known exactly when or how he died but it has been suggested he was killed during the siege of Ojinaga in January, 1914.

Primary Sources

(1) Ambrose Bierce was influenced by his uncle, Lucius Bierce, a campaigner against slavery. When John Brown was executed, Bierce made a speech that was reported in the Summit Beacon in Ohio (7th December, 1859)

The tragedy of Brown's is freighted with awful lessons and consequences. It is like the clock striking the fatal hour that begins a new era in the conflict with slavery. Men like Brown may die, but their acts and principles will live forever. Call it fanaticism, folly, madness, wickedness, but until virtue becomes fanaticism, divine wisdom folly, obedience to God madness, and piety wickedness, John Brown, inspired with these high and holy teachings, will rise up before the world with his calm, marble features, most terrible in death and defeat, than in life and victory. It is one of those acts of madness which history cherished and poetry loves forever to adorn with her choicest wreaths of laurel.

(2) Ambrose Bierce took part in his first battle at Laurel Hill on 10th July, 1861.

Just before nightfall one day occurred the one really sharp little fight that we had. It has been represented as a victory for us, but it was not. A few dozen of us, who had been swapping shots with the enemy's skirmishers, grew tired of the resultless battle, and by a common impulse, and I think without orders or officers, ran forward into the woods and attacked the Confederate works. We did well enough, considering the hopeless folly of the movement, but we came out of the woods faster than we went in, a good deal.

(3) After the war Ambrose Bierce wrote an article, What I Saw of Shiloh, about arriving with General Don Carlos Buell after the Battle of Shiloh.

There were men enough; all dead, apparently, except one, who lay near where I halted my platoon to await the slower movements of the line - a federal sergeant, variously hurt, who had been a fine giant in his time. He lay face upward, taking in his breath in convulsive, rattling snorts, and blowing it out in sputters of froth which crawled creamily down his cheek, piling itself alongside his neck and ears. A bullet had clipped a groove in his skull, above the temple; from this the brain protruded in bosses, dropping off in flakes and strings.

The woods had caught fire and the bodies had been cremated. They lay, half buried in ashes; some in the unlovely looseness of attitude denoting sudden death by the bullet, but by far the greater number in postures of agony that told of the tormenting flames. Their clothing was half burnt away - their hair and beard entirely; the rain had come too late to save their nails. Some were swollen to double girth; others shriveled to manikins. According to degree of exposure, their faces were bloated and black or yellow and shrunken. The contraction of muscles which had given claws for hands had cursed each countenance with a hideous grin.

(4) Ambrose Bierce, San Francisco Examiner (17th August, 1890)

It was once my fortune to command a company of soldiers - real soldiers. Not professional life-long fighters, the product of European militarism - just plain, ordinary, American, volunteer soldiers, who loved their country and fought for it with never a thought of grabbing it for themselves; that is a trick which the survivors were taught later by gentlemen desiring their votes.

(5) General William Hazen, military report (23rd June, 1864)

While engaged in this duty, Lieutenant Bierce was shot in the head by a musket ball which caused a very dangerous and complicated wound, the ball remained within the head from which it was removed sometime afterwards.

(6) Ambrose Bierce, Argonaut (9th February, 1879)

For nearly all that is good in our American civilization we are indebted to England; the errors and mischiefs are of our own creation. In learning and letters, in art and the science of government, America is but a faint and stammering echo of England.

(7) Ambrose Bierce, The Socialist (1894)

The socialist notion appears to be that the world's wealth is a fixed quantity, and A can acquire only by depriving B. He is fond of figuring the rich as living upon the poor - riding on their backs. The plain truth of the matter is that the poor live mostly on the rich.

(8) Ambrose Bierce, speech on Socialism in New York (July, 1906)

Nothing touches me more than poverty. I have been poor myself. I was one of those poor devils born to work as a peasant in the fields, but I found no difficulty getting out of it. I don't see that there is any remedy for the condition which consists in the rich being on top. They always will be. The reason that rich men are poor - this is not a rule without an exception - is that they are incapable. The rich become rich because they have brains.

(9) Charles Edward Russell, Hampton's Magazine (September, 1910)

These articles (about Collis Huntington) were extraordinary examples of invective and bitter sarcasm. After a time the skill and steady persistence of the attack began to draw attention. With six months of incessant firing, Mr. Bierce had the railroad forces frightened and wavering; and before the end of the year, he had them whipped.