On this day on 23rd August

On this day in 1305 William Wallace is executed for high treason at Smithfield. Wallace emerged as a Scottish leader after the defeat of John Balliol in 1296. The following year Wallace and Andrew Moray led a rebellion against the English. His most famous victory was at Stirling Bridge in September 1297, where Scottish infantrymen were able to defeat a large English army of mounted knights.

After the death of Moray in 1297 Wallace became the undisputed leader of the Scots. Wallace continued to create problems for the English army until he was captured in 1305 and executed.

On this day in 1532 The London Chronicle reports that women are being punished for giving their support to Catherine of Aragon over Anne Boleyn.

"The 23rd day of August were two women beaten... naked from the waist upwards with rods and their ears nailed to the standard for because they said Queen Catherine was the true queen of England and not Queen Anne. And one of the women was big with child. And when these two women had thus been punished, they fortified their saying still, to die in the quarrel for Queen Catherine's sake."

On this day in 1852 Arnold Toynbee was born in London. Educated at private schools at Blackheath and Woolwich, he attended Pembroke College (1873-74) and Balliol College (1875-78). After graduating in 1878 he became a lecturer in political economy at Oxford University.

Toynbee investigated the science of economics where he attempted to develop a system that would improve the condition of the working class. Toynbee came to the conclusion that individuals had a duty to devote themselves to the service of humanity.

A supporter of the co-operative movement and working class education, Arnold Toynbee died at the age of thirty on 9th March 1883. Toynbee's famous book, The Industrial Revolution in England was published after his death. In 1884 Toynbee Hall in Whitechapel, East London, was founded in his memory.

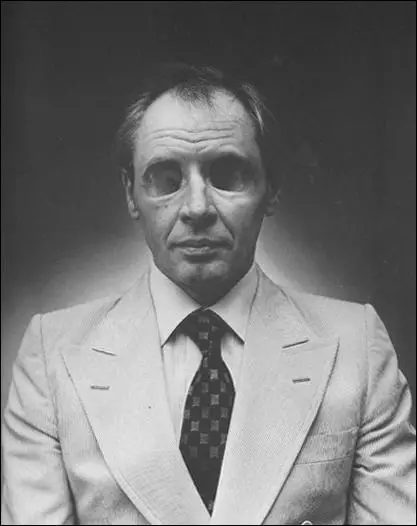

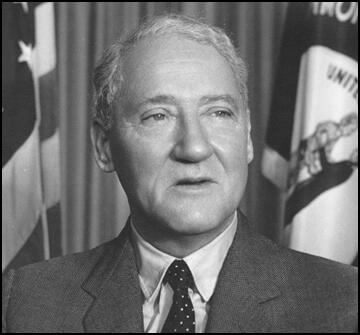

On this day in 1901 John Sherman Cooper was born in Somerset, Kentucky. After graduating from Yale College in attended Harvard Law School. He was admitted to bar in 1928 and worked as a lawyer in Somerset, Kentucky.

A member of the Republican Party, Cooper was elected to the House of Representatives in Kentucky in 1928 and served as judge of Pulaski County (1930-38).

During the Second World War Cooper served in the United States Army where he he attained the rank of captain. In 1946 Cooper was elected to the Senate.

Cooper lived in Washington where he associated with a group of journalists, politicians and government officials that became known as the Georgetown Set. This included Frank Wisner, George Kennan, Dean Acheson, Richard Bissell, Desmond FitzGerald, Joseph Alsop, Stewart Alsop, Tracy Barnes, Thomas Braden, Philip Graham, David Bruce, Clark Clifford, Walt Rostow, Eugene Rostow, Chip Bohlen, Cord Meyer, James Angleton, William Averill Harriman, John McCloy, Felix Frankfurter, Allen W. Dulles and Paul Nitze.

Most men brought their wives to these gatherings. Members of what was later called the Georgetown Ladies' Social Club included Katharine Graham, Mary Pinchot Meyer, Sally Reston, Polly Wisner, Joan Braden, Lorraine Cooper, Evangeline Bruce, Avis Bohlen, Janet Barnes, Tish Alsop, Cynthia Helms, Marietta FitzGerald, Phyllis Nitze and Annie Bissell.

After losing his seat in 1949 he returned to his legal practice. Later that year he was appointed delegate to the General Assembly of the United Nations and in as adviser to the Council of Ministers of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization in 1950.

In 1952 Cooper was again elected to the Senate. A strong opponent of McCarthyism Copper was one of the first senators to attack the tactics of Joseph McCarthy. After losing his seat he was appointed Ambassador to India (1955-56). Cooper was elected to the Senate for the third time in 1956.

After the death of John F. Kennedy, his deputy, Lyndon B. Johnson, was appointed president. He immediately set up a commission to "ascertain, evaluate and report upon the facts relating to the assassination of the late President John F. Kennedy." The seven man commission was headed by Chief Justice Earl Warren and included John Sherman Cooper, Gerald Ford, Allen W. Dulles, John J. McCloy, Richard B. Russell and Thomas H. Boggs.

The Warren Commission was published in October, 1964. It reached the following conclusions: "(1) The shots which killed President Kennedy and wounded Governor Connally were fired from the sixth floor window at the southeast corner of the Texas School Book Depository. (2) The weight of the evidence indicates that there were three shots fired. (3) Although it is not necessary to any essential findings of the Commission to determine just which shot hit Governor Connally, there is very persuasive evidence from the experts to indicate that the same bullet which pierced the President's throat also caused Governor Connally's wounds.... (4) The shots which killed President Kennedy and wounded Governor Connally were fired by Lee Harvey Oswald. (5) Oswald killed Dallas Police Patrolman J. D. Tippit approximately 45 minutes after the assassination. (6) Within 80 minutes of the assassination and 35 minutes of the Tippit killing Oswald resisted arrest at the theater by attempting to shoot another Dallas police officer. (7) The Commission has found no evidence that either Lee Harvey Oswald or Jack Ruby was part of any conspiracy, domestic or foreign, to assassinate President Kennedy. (8) In its entire investigation the Commission has found no evidence of conspiracy, subversion, or disloyalty to the U.S. Government by any Federal, State, or local official. (9) On the basis of the evidence before the Commission it concludes that, Oswald acted alone."

According to Gerald D. McKnight, the author of Breach of Trust: How the Warren Commission Failed the Nation and Why (2000): "Although Russell had support from Cooper and Boggs, he was the only one who actively dug in his heels against Rankin and the staff's contention that Kennedy and Connally had been hit by the same nonfatal bullet. Because of Russell's chronic Commission absenteeism he never fully comprehended that the final report's no-conspiracy conclusion was inextricably tied to the validity of what would later be referred to as the single-bullet theory."

The journalist, C. David Heymann, has argued: "Of JFK's many friends and admirers none was more anguished by his death than John Sherman Cooper. The Kentucky senator subsequently served on both the Warren Commission and on the committee selected by Jacqueline and Robert Kennedy to select a site and raise funds for the John F. Kennedy Library. Regarding his service on the Warren Commission, Senator Cooper publicly expressed dissatisfaction with the commission's findings, terming the group's 1964 report 'premature and inconclusive.' In no uncertain terms he informed Jack's surviving brothers, Robert and Teddy, that, having personally examined thousands of shreds of documentation, he felt strongly that Lee Harvey Oswald had not acted alone." Heymann claims that when Cooper expressed these thoughts to Jackie Kennedy, she responded: "What difference does it make? Knowing who killed him won't bring Jack back." Cooper replied: "No, it won't... But it's important for this nation that we bring the true murderers to justice."

Cooper was a critic of U.S. involvement in Vietnam. In 1969, he joined with Senator Frank Church to sponsor an amendment prohibiting the use of ground troops in Laos and Thailand. The two men also joined forces in 1970 to limit the power of the president during a war.

After leaving Senate in 1973, Cooper was appointed Ambassador to the German Democratic Republic (1974-76).

John Sherman Cooper died in Washington on 21st February, 1991.

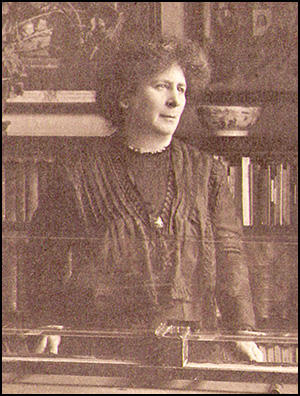

On this day in 1923 suffragette Hertha Ayrton died.

Phoebe (Hertha) Marks, the daughter of a watchmaker, was born in Portsea, Hampshire, on 28th April 1854. She was educated at home and one of her tutors was Eliza Orme, who taught her mathematics. From the age of sixteen she worked as a governess. She adopted the name "Hertha" after the heroine of an Algernon Charles Swinburne poem that criticized organized religion.

In 1875 Orme wrote to Helen Taylor, to tell her about the desire of Hertha to study mathematics at Girton College. With the financial help of Taylor and Barbara Bodichon she was able to attend Girton between 1877 and 1881.

After leaving university she taught at Notting Hill and Ealing High School. In 1872 Hertha Marks joined the Hampstead branch of the Central Society for Women's Suffrage. In 1885 the line divider she had invented and patented was shown at the Exhibition of Women's Industries organised in Bristol by Helen Blackburn. In 1885 she married Professor William Ayrton, a widower whose first wife, Matilda Chaplin Ayrton (1846-1883), had been a doctor and a member of the London National Society for Women's Suffrage. He was the father of Edith Ayrton, who was later to play a significant role in the struggle for women's suffrage. Hertha's daughter, Barbara Ayrton, was born in 1886.

Hertha Ayrton continued with her scientific research, working from a laboratory in her house. She also remained active in the London National Society for Women's Suffrage and the National Union of Suffrage Societies. Frustrated by the lack of progress in achieving the vote she accepted that a more militant approach was needed and in 1907 she joined the Women Social & Political Union. Left a considerable amount of money by Barbara Bodichon, she also gave generously to the WSPU. The 1909-10 WSPU accounts show that she gave £1,060 in that year. In 1910 she joined Emmeline Pankhurst and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson in a deputation to the House of Commons.

In a letter she wrote to Maud Arncliffe Sennett, Hertha admitted: "I made up my mind some time ago that as I am unable to be militant myself, from reasons of health, and as I believe most fully in the necessity for militancy, I was bound to give every penny I can afford to the militant union that is bearing the brunt of the battle, namely the WSPU."

In March 1912 the British government made it clear that they intended to seize the assets of the WSPU. According to Evelyn Sharp Hertha Ayrton helped to "launder" through her bank account the funds of the WSPU. The WSPU bank manager was subpoenaed to appear at the conspiracy trial and revealed that £7,000 had been paid to "someone named Ayrton".

In November 1912 Hertha Ayrton helped form the Jewish League for Woman Suffrage. The main objective was "to demand the Parliamentary Franchise for women, on the same terms as it is, or may be, granted to men." One member wrote that "it was felt by a great number that a Jewish League should be formed to unite Jewish Suffragists of all shades of opinions, and that many would join a Jewish League where, otherwise, they would hesitate to join a purely political society." Other members included Edith Ayrton, Henrietta Franklin, Hugh Franklin, Lily Montagu, Inez Bensusan and Israel Zangwill.

Militants in the Jewish League for Woman Suffrage disrupted Sabbath worship services in several synagogues in London from early 1913 until the outbreak of First World War, demanding religious as well as political suffrage for women. These women were forcibly removed from synagogues for disrupting services and castigated in the Anglo-Jewish press as “blackguards in bonnets.”

The summer of 1913 saw a further escalation of WSPU violence. In July attempts were made by suffragettes to burn down the houses of two members of the government who opposed women having the vote. These attempts failed but soon afterwards, a house being built for David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was badly damaged by suffragettes. This was followed by cricket pavilions, racecourse stands and golf clubhouses being set on fire.

Some leaders of the WSPU such as Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, disagreed with this arson campaign. When Pethick-Lawrence objected, she was expelled from the organisation. Others like Louisa Garrett Anderson and Elizabeth Robins showed their disapproval by ceasing to be active in the WSPU. Sylvia Pankhurst also made her final break with the WSPU and concentrated her efforts on helping the Labour Party build up its support in London. During this period Hertha Ayrton stopped funding the WSPU.

In February 1914 Hertha became a leading member of the United Suffragists. The group were disillusioned by the lack of success of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies and disapproved of the arson campaign of the Women Social & Political Union, decided to form a new organisation. Membership was open to both men and women, militants and non-militants. Members included Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Evelyn Sharp, Henry Nevinson, Margaret Nevinson, Edith Ayrton, Israel Zangwill, Lena Ashwell, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Eveline Haverfield, Maud Arncliffe Sennett, John Scurr, Julia Scurr and Laurence Housman.

During the First World War Hertha Ayrton devised a simple anti-gas fan that could be used in the trenches on the Western Front. Unfortunately, she was unable to persuade the British Army to employ the device.

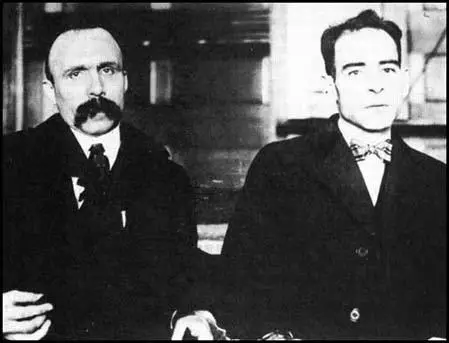

On this day in 1927 Italian anarchists Bartolomeo Vanzetti and Nicola Sacco are executed.

On 15th April, 1920, Frederick Parmenter and Alessandro Berardelli, in South Braintree, were shot dead while carrying two boxes containing the payroll of a shoe factory. After the two robbers took the $15,000 they got into a car containing several other men and were driven away.

Several eyewitnesses claimed that the robbers looked Italian. A large number of Italian immigrants were questioned but eventually the authorities decided to charge Bartolomeo Vanzetti and Nicola Sacco with the murders. Although the two men did not have criminal records, it was argued that they had committed the robbery to acquire funds for their anarchist political campaign.

Fred H. Moore, a socialist lawyer, agreed to defend the two men. Eugene Lyons, a young journalist, carried out research for Moore. Lyons later recalled: "Fred Moore, by the time I left for Italy, was in full command of an obscure case in Boston involving a fishmonger named Bartolomeo Vanzetti and a shoemaker named Nicola Sacco. He had given me explicit instructions to arouse all of Italy to the significance of the Massachusetts murder case, and to hunt up certain witnesses and evidence. The Italian labor movement, however, had other things to worry about. An ex-socialist named Benito Mussolini and a locust plague of blackshirts, for instance. Somehow I did get pieces about Sacco and Vanzetti into Avanti!, which Mussolini had once edited, and into one or two other papers. I even managed to stir up a few socialist onorevoles, like Deputy Mucci from Sacco's native village in Puglia, and Deputy Misiano, a Sicilian firebrand at the extreme Left. Mucci brought the Sacco-Vanzetti affair to the floor of the Chamber of Deputies, the first jet of foreign protest in what was eventually to become a pounding international flood."

The trial started on 21st May, 1921. The main evidence against the men was that they were both carrying a gun when arrested. Some people who saw the crime taking place identified Bartolomeo Vanzetti and Nicola Sacco as the robbers. Others disagreed and both men had good alibis. Vanzetti was selling fish in Plymouth while Sacco was in Boston with his wife having his photograph taken. The prosecution made a great deal of the fact that all those called to provide evidence to support these alibis were also Italian immigrants.

Vanzetti and Sacco were disadvantaged by not having a full grasp of the English language. Webster Thayer, the judge was clearly prejudiced against anarchists. The previous year, he rebuked a jury for acquitting anarchist Sergie Zuboff of violating the criminal anarchy statute. It was clear from some of the answers Vanzetti and Sacco gave in court that they had misunderstood the question. During the trial the prosecution emphasized the men's radical political beliefs. Vanzetti and Sacco were also accused of unpatriotic behaviour by fleeing to Mexico during the First World War.

Eugene Lyons has argued in his autobiography, Assignment in Utopia (1937): "Fred Moore was at heart an artist. Instinctively he recognized the materials of a world issue in what appeared to others a routine matter... When the case grew into a historical tussle, these men were utterly bewildered. But Moore saw its magnitude from the first. His legal tactics have been the subject of dispute and recrimination. I think that there is some color of truth, indeed, to the charge that he sometimes subordinated the literal needs of legalistic procedure to the larger needs of the case as a symbol of class struggle. If he had not done so, Sacco and Vanzetti would have died six years earlier, without the solace of martyrdom. With the deliberation of a composer evolving the details of a symphony which he senses in its rounded entirety, Moore proceeded to clarify and deepen the elements implicit in the case. And first of all he aimed to delineate the class character of the automatic prejudices that were operating against Sacco and Vanzetti. Sometimes over the protests of the men themselves he cut through legalistic conventions to reveal underlying motives. Small wonder that the pinched, dyspeptic judge and the pettifogging lawyers came to hate Moore with a hatred that was admiration turned inside out."

In court Nicola Sacco claimed: "I know the sentence will be between two classes, the oppressed class and the rich class, and there will be always collision between one and the other. We fraternize the people with the books, with the literature. You persecute the people, tyrannize them and kill them. We try the education of people always. You try to put a path between us and some other nationality that hates each other. That is why I am here today on this bench, for having been of the oppressed class. Well, you are the oppressor." The trial lasted seven weeks and on 14th July, 1921, both men were found guilty of first degree murder and sentenced to death. The journalist. Heywood Broun, reported that when Judge Thayer passed sentence upon Sacco and Vanzetti, a woman in the courtroom said with terror: "It is death condemning life!"

Bartolomeo Vanzetti commented in court after the sentence was announced: "The jury were hating us because we were against the war, and the jury don't know that it makes any difference between a man that is against the war because he believes that the war is unjust, because he hate no country, because he is a cosmopolitan, and a man that is against the war because he is in favor of the other country that fights against the country in which he is, and therefore a spy, an enemy, and he commits any crime in the country in which he is in behalf of the other country in order to serve the other country. We are not men of that kind. Nobody can say that we are German spies or spies of any kind... I never committed a crime in my life - I have never stolen and I have never killed and I have never spilt blood, and I have fought against crime, and I have fought and I have sacrificed myself even to eliminate the crimes that the law and the church legitimate and sanctify."

Many observers believed that their conviction resulted from prejudice against them as Italian immigrants and because they held radical political beliefs. The case resulted in anti-US demonstrations in several European countries and at one of these in Paris, a bomb exploded killing twenty people.

In 1925 Celestino Madeiros, a Portuguese immigrant, confessed to being a member of the gang that killed Frederick Parmenter and Alessandro Berardelli. He also named the four other men, Joe, Fred, Pasquale and Mike Morelli, who had taken part in the robbery. The Morelli brothers were well-known criminals who had carried out similar robberies in area of Massachusetts. However, the authorities refused to investigate the confession made by Madeiros.

Important figures in the United States and Europe became involved in the campaign to overturn the conviction. John Dos Passos, Alice Hamilton, Paul Kellog, Jane Addams, Heywood Broun, William Patterson, Upton Sinclair, Dorothy Parker, Ruth Hale, Ben Shahn, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Felix Frankfurter, Susan Gaspell, Mary Heaton Vorse, Gardner Jackson, John Howard Lawson, Freda Kirchway, Floyd Dell, Katherine Anne Porter, Michael Gold, Bertrand Russell, John Galsworthy, Arnold Bennett, George Bernard Shaw and H. G. Wells became involved in a campaign to obtain a retrial. Although Webster Thayer, the original judge, was officially criticised for his conduct at the trial, the authorities refused to overrule the decision to execute the men. One of the campaigners, Anatole France, commented: "The death of Sacco and Vanzetti will make martyrs of them and cover you with shame. Save them for your honor, for the honor of your children, and for the generations yet unborn."

Eugene Debs, the leader of the Socialist Party of America, called for trade union action against the decision: "The supreme court of Massachusetts has spoken at last and Bartolomeo Vanzetti and Nicola Sacco, two of the bravest and best scouts that ever served the labor movement, must go to the electric chair.... Now is the time for all labor to be aroused and to rally as one vast host to vindicate its assailed honor, to assert its self-respect, and to issue its demand that in spite of the capitalist-controlled courts of Massachusetts honest and innocent working-men whose only crime is their innocence of crime and their loyalty to labor, shall not be murdered by the official hirelings of the corporate powers that rule and tyrannize over the state."

In 1927 Governor Alvan T. Fuller appointed a three-member panel of Harvard President Abbott Lawrence Lowell, the President of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Samuel W. Stratton, and the novelist, Robert Grant to conduct a complete review of the case and determine if the trials were fair. The committee reported that no new trial was called for and based on that assessment Governor Fuller refused to delay their executions or grant clemency. Walter Lippmann, who had been one of the main campaigners for Sacco and Vanzetti, argued that Governor Fuller had "sought with every conscious effort to learn the truth" and that it was time to let the matter drop.

Heywood Broun disagreed and on 5th August he wrote in New York World: "Alvan T. Fuller never had any intention in all his investigation but to put a new and higher polish upon the proceedings. The justice of the business was not his concern. He hoped to make it respectable. He called old men from high places to stand behind his chair so that he might seem to speak with all the authority of a high priest or a Pilate. What more can these immigrants from Italy expect? It is not every prisoner who has a President of Harvard University throw on the switch for him. And Robert Grant is not only a former Judge but one of the most popular dinner guests in Boston. If this is a lynching, at least the fish peddler and his friend the factory hand may take unction to their souls that they will die at the hands of men in dinner coats or academic gowns, according to the conventionalities required by the hour of execution."

The following day Broun returned to the attack. He argued that Governor Alvan T. Fuller had vindicated Judge Webster Thayer "of prejudice wholly upon the testimony of the record". Broun had pointed out that Fuller had "overlooked entirely the large amount of testimony from reliable witnesses that the Judge spoke bitterly of the prisoners while the trial was on." Broun added: "It is just as important to consider Thayer's mood during the proceedings as to look over the words which he uttered. Since the denial of the last appeal, Thayer has been most reticent, and has declared that it is his practice never to make public statements concerning any judicial matters which come before him. Possibly he never did make public statements, but certainly there is a mass of testimony from unimpeachable persons that he was not so careful in locker rooms and trains and club lounges."

It now became clear that Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti would be executed. Vanzetti commented to a journalist: "If it had not been for this thing, I might have lived out my life talking at street corners to scorning men. I might have died, unmarked, unknown, a failure. Now we are not a failure. This is our career and our triumph. Never in our full life can we hope to do such work for tolerance, justice, for man's understanding of man, as now we do by accident. Our words - our lives - our pains - nothing! The taking of our lives - lives of a good shoemaker and a poor fish peddler - all! That last moment belong to us - that agony is our triumph. On 23rd August 1927, the day of execution, over 250,000 people took part in a silent demonstration in Boston.

Soon after the executions Eugene Lyons published his book, The Life and Death of Sacco and Vanzetti (1927): "It was not a frame-up in the ordinary sense of the word. It was a far more terrible conspiracy: the almost automatic clicking of the machinery of government spelling out death for two men with the utmost serenity. No more laws were stretched or violated than in most other criminal cases. No more stool-pigeons were used. No more prosecution tricks were played. Only in this case every trick worked with a deadly precision. The rigid mechanism of legal procedure was at its most unbending. The human beings who operated the mechanism were guided by dim, vague, deep-seated motives of fear and self-interest. It was a frame-up implicit in the social structure. It was a perfect example of the functioning of class justice, in which every judge, juror, police officer, editor, governor and college president played his appointed role easily and without undue violence to his conscience. A few even played it with an exalted sense of their own patriotism and nobility."

The United States system of justice came under attack from important figures throughout the world. Bertrand Russell argued: "I am forced to conclude that they were condemned on account of their political opinions and that men who ought to have known better allowed themselves to express misleading views as to the evidence because they held that men with such opinions have no right to live. A view of this sort is one which is very dangerous, since it transfers from the theological to the political sphere a form of persecution which it was thought that civilized countries had outgrown."

The novelist, Upton Sinclair, decided to investigate the case. He interviewed Fred H. Moore, one of defence lawyers in the case. According to Sinclair's latest biographer, Anthony Arthur: "Fred Moore, Sinclair said later, who confirmed his own growing doubts about Sacco's and Vanzetti's innocence. Meeting in a hotel room in Denver on his way home from Boston, he and Moore talked about the case. Moore said neither man ever admitted it to him, but he was certain of Sacco's guilt and fairly sure of Vanzetti's knowledge of the crime if not his complicity in it." A letter written by Sinclair at the time acknowledged that he had doubts about Moore's testimony: "I realized certain facts about Fred Moore. I had heard that he was using drugs. I knew that he had parted from the defense committee after the bitterest of quarrels.... Moore admitted to me that the men themselves had never admitted their guilt to him, and I began to wonder whether his present attitude and conclusions might not be the result of his brooding on his wrongs."

Sinclair was now uncertain if a miscarriage of justice had taken place. He decided to end the novel on a note of ambiguity concerning the guilt or innocence of the Italian anarchists. When Robert Minor, a leading figure in the American Communist Party, discovered Sinclair's intentions he telephoned him and said: "You will ruin the movement! It will be treason!" Sinclair's novel, Boston, appeared in 1928. Unlike some of his earlier radical work, the novel received very good reviews. The New York Times called it a "literary achievement" and that it was "full of sharp observation and savage characterization," demonstrating a new "craftsmanship in the technique of the novel".

Fifty years later, on 23rd August, 1977, Michael Dukakis, the Governor of Massachusetts, issued a proclamation, effectively absolving the two men of the crime. "Today is the Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti Memorial Day. The atmosphere of their trial and appeals were permeated by prejudice against foreigners and hostility toward unorthodox political views. The conduct of many of the officials involved in the case shed serious doubt on their willingness and ability to conduct the prosecution and trial fairly and impartially. Simple decency and compassion, as well as respect for truth and an enduring commitment to our nation's highest ideals, require that the fate of Sacco and Vanzetti be pondered by all who cherish tolerance, justice and human understanding."

On this day in 1936 The Observer reports that Gregory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev are guilty of plotting against Joseph Stalin. "It is futile to think the trial was staged and the charges trumped up. The government's case against the defendants (Zinoviev and Kamenev) is genuine."

In July 1936 Nikolai Yezhov, the head of the NKVD, told Zinoviev and Kamenev that their children would be charged with being part of the conspiracy to kill Sergey Kirov, and would face execution if found guilty. The two men now agreed to co-operate at the trial if Joseph Stalinpromised to spare their lives. At a meeting with Stalin, Kamenev told him that they would agree to co-operate on the condition that none of the old-line Bolsheviks who were considered the opposition and charged at the new trial would be executed, that their families would not be persecuted, and that in the future none of the former members of the opposition would be subjected to the death penalty. Stalin replied: "That goes without saying!"

The trial opened on 19th August 1936. Five of the sixteen defendants were actually NKVD plants, whose confessional testimony was expected to solidify the state's case by exposing Zinoviev, Kamenev and the other defendants as their fellow conspirators. The presiding judge was Vasily Ulrikh, a member of the secret police. The prosecutor was Andrei Vyshinsky, who was to become well-known during the Show Trials over the next few years.

Yuri Piatakov accepted the post of chief witness "with all my heart." Max Shachtman pointed out: "The official indictment charges a widespread assassination conspiracy, carried on these five years or more, directed against the head of the Communist party and the government, organized with the direct connivance of the Hitler regime, and aimed at the establishment of a Fascist dictatorship in Russia. And who are included in these stupefying charges, either as direct participants or, what would be no less reprehensible, as persons with knowledge of the conspiracy who failed to disclose it?"

The men made confessions of their guilt. Lev Kamenev said: "I Kamenev, together with Zinoviev and Trotsky, organised and guided this conspiracy. My motives? I had become convinced that the party's - Stalin's policy - was successful and victorious. We, the opposition, had banked on a split in the party; but this hope proved groundless. We could no longer count on any serious domestic difficulties to allow us to overthrow. Stalin's leadership we were actuated by boundless hatred and by lust of power."

Gregory Zinoviev also confessed: "I would like to repeat that I am fully and utterly guilty. I am guilty of having been the organizer, second only to Trotsky, of that block whose chosen task was the killing of Stalin. I was the principal organizer of Kirov's assassination. The party saw where we were going, and warned us; Stalin warned as scores of times; but we did not heed these warnings. We entered into an alliance with Trotsky."

Kamenev's final words in the trial concerned the plight of his children: "I should like to say a few words to my children. I have two children, one is an army pilot, the other a Young Pioneer. Whatever my sentence may be, I consider it just... Together with the people, follow where Stalin leads." This was a reference to the promise that Stalin made about his sons.

On 24th August, 1936, Vasily Ulrikh entered the courtroom and began reading the long and dull summation leading up to the verdict. Ulrikh announced that all sixteen defendants were sentenced to death by shooting. Edward P. Gazur has pointed out: "Those in attendance fully expected the customary addendum which was used in political trials that stipulated that the sentence was commuted by reason of a defendant's contribution to the Revolution. These words never came, and it was apparent that the death sentence was final when Ulrikh placed the summation on his desk and left the court-room." The following day Soviet newspapers carried the announcement that all sixteen defendants had been put to death.

On this day in 1989 psychiatrist R. D. Laing, while on holiday in St Tropez, he felt unwell. "This may be the day" he remarked to Marguerite. Despite this worry, that afternoon he played a vigorous game of tennis. During the game he suffered a heart-attack and died in the arms of his 19 year-old daughter, Natatsha.

Laing published Sanity, Madness and the Family in 1964. This research project included one hundred female schizophrenics and their families. Once the patient and her parents and other family members had agreed to participate, Laing and Esterson conducted interviews with the patient alone, then together with the other family members, and then finally alone with her parents. All the interviews were recorded and subsequently transcribed.

One of the case studies involved the seventeen year old Ruby Eden who was originally admitted to hospital in an inaccessible catatonic stupor. She had recently had an unwanted pregnancy and subsequent miscarriage. She complained of hearing voices, calling her "slut", "dirty" and "prostitute". Ruby was also convinced that her family disliked her and wanted to get rid of her. In 22 hours of interviews with Ruby and her family uncovered a "miasma of deceit" concerning the relationships between family members. Laing commented that "the most intricate splits and denials in her perception of herself and others were simultaneously expected of this girl and practised by the others".

Ruby was the illegitimate offspring of a liason between her mother and a married man who visited occasionally, whom Ruby called "uncle". Cast out by her own father, Ruby's mother was given sanctuary by her own sister and her brother-in-law whom Ruby was encouraged to call "daddy". Ruby was told about her illegitimacy and her mother's attempts to abort her. Laing argues that the main problem is the physical attraction that Ruby shows towards her uncle: "She won't leave me in peace - she's always stroking me, pawing me... I won't pamper like her mother and aunt. If I pampered her she'd stop pawing me but I don't."

Ruby believes that the neighbours are highly critical of her behaviour. Her mother rejects this idea: "They are so kind to her. They're all interested in her welfare. No one has said a word to her about it or going into hospital, not a word, there's no gossip. I don't know what Ruby should think the neighbours are talking about her." Her aunt agrees: "Nobody's ever been unkind to her... Ruby is the one who can't keep things to herself. She'll tell everyone her business."

R. D. Laing argued that the claustrophobic nature of many of the families suggests a "form of subtle emotional blackmail, a killing by kindness". This makes daughters feel restricted, with no life of their own and unable to healthily separate from their parents. In the book, Laing maintained that "schizophrenia was a strategy which a person invented in order to live in an unlivable situation".

The publication of Sanity, Madness and the Family brought him to the attention of the wider public. In 1964 Laing appeared on UK television on five occasions. He wrote in his diary: "I feel I am going to become famous, and receive recognition. Most of my work has not hit the public yet, eventually it will, like the light from a dead star".

In November 1964, he published an article in the New Left Review entitled "What is Schizophrenia?". He argued that "I do not myself believe that there is any such 'condition' as 'schizophrenia'. Yet the label as social fact, is a political event. This political event, occurring in the civic order of society, imposes definitions and consequences on the labelled person. It is a social prescription that rationalizes a set of social actions whereby the labelled person is annexed by others, who are legally sanctioned, medically empowered, and morally obliged, to become responsible for the person labelled... After being subjected to a degradation ceremonial known as psychiatric examination he is bereft on his civil liberties in being imprisoned in a total institution known as a 'mental hospital'. More completely, more radically than anywhere else in our society he is invalidated as a human being."

In 1965 a paperback version of The Divided Self was published. This created a sensation and over the next few years it sold over 700,000 copies and was translated into nearly every language spoken throughout the world including Arabic, Hebrew and Japanese. As one of his biographers, Charles Rycroft, pointed out: "This idea that schizophrenics and, by extension, neurotics are victims, the damaged but heroic survivors of impossible inhuman family and social pressures, was, coupled with Laing's charm and literary skill, largely responsible for the fact that he became a leading cult figure of the counter-culture of the 1960s."

The Politics of Experience and the Bird of Paradise was published in 1967. It was a collection of lectures that had been delivered over the last five years. The material "provided a unified philosophical perspective on the nature of madness", which owed more to his studies of Karl Marx, Jean-Paul Sartre and Friedrich Nietzsche than any clinical work on psychiatry.

R. D. Laing, upset the medical profession when he argued that psychiatrists could give little help to people who were suffering from mental illness. In fact, they could do a great deal of harm: "Many patients in their innocence continue to flock for help to psychiatrists who honestly feel they are giving people what they ask for: relief from suffering. This is but one example of the diametric irrationality of much of our social scene. The exact opposite is achieved to what is intended. Doctors in all ages have made fortunes by killing their patients by means of their cures. The difference in psychiatry is that it is the death of the soul."

Laing also illustrated the role in the family in mental health problems: "The Family's function is to repress Eros: to induce a false consciousness of security: to deny death by avoiding life: to cut off transcendence: to believe in God, not to experience the Void: to create, in short one-dimensional man: to promote respect, conformity, obedience: to con children out of play: to induce a fear of failure: to promote a respect for work: to promote a respect for respectability".

The book was "the fulsome and unrestrained attack on almost every conceivable social institution including the family, psychiatric hospitals, the church, schools and the educational system, political and scientific organisations and, of course, the processes of conformity and so-called 'normality'. His language was angry, violent, political and apocalyptic."

Laing pointed out: "A child born today in the UK stands a ten times greater chance of being admitted to a mental hospital than to a university, and about one fifth of mental hospital admissions are diagnosed schizophrenic. This can be taken as an indication that we are driving our children mad more effectively than we are genuinely educating them. Perhaps it is our very way of educating them that is driving them mad."

The Politics of Experience and the Bird of Paradise received a hostile reception from the profession. The review in the British Journal of Psychiatry commented: "Surely the young people who turn to Laing for help deserve to know what he is wearing, what role he offers them, what model he uses, what authority he speaks from. In this book, he offers three models which can be disentangled only with the greatest difficulty. None of them is the medical model, from which we believe he derived his authority. If Laing wishes to be a guru or a philosopher, there is no doubt a place for him, but young people who are suffering from schizophrenia may prefer to entrust themselves to a doctor who will treat their illness as best he can."

Richard Sennett wrote in the New York Times that he was very disappointed by Laing's political development. "By the time Laing wrote The Politics of Experience (1967), it seemed logical that he would become a social analyst, a man whose experience as a psychiatrist would give him, and his readers, new insights into how society organized repression. But these insights were not forthcoming. Rather than follow the logic of his own anger and become a social critic, he chose to make his patients, whom he had formerly seen as dignified in their suffering, into heroes. He dealt with society only by clinging to those people who were its victims and whose actions, if not intentions, showed they were fighting back."

Ronnie's relationship with Anne was "less than fulfilling, and at times excruciating painful." According to one source they "argued so loudly and ferociously that their neighbours complained". Laing began a relationship with the journalist Sally Vincent, who found Laing "endearingly and emotionally very expressive, and that he would unselfconsciously burst into tears at the cinema or theatre". However, she also found that "at times he could be brutally frank, and refused to provide either socially-expected answers or conversation". Vincent admitted "Ronnie was brilliant, a complete original, but he desperately overdid the drugs and drink ... He would be lying on the floor, paralytic but talking nonstop and making perfect sense." However, she found Laing difficult to live with and eventually the relationship came to an end and he returned to Anne Laing.

R. D. Laing then spent time in France where he resumed his relationship with Marcelle Vincent. She arranged for him to meet the French philosopher, Jean-Paul Sartre. The two men had a two-hour conversation about politics and philosophy. Laing argued that for Sartre, psychoanalysis is "above all an illumination of the present acts and experience of a person in terms of the way he has lived his family relationships". In 1968 R. D. Laing was invited to provide a series of lectures in honour of Vincent Massey, the former Governor-General of Canada. The five lectures were broadcast on radio by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. The lectures were entitled: "The Family, Invalidation and the Clinical Conspiracy"; "Family Scenarios: Paradigms and Projection"; "The Family and the Sense of Reality"; "Beyond Repression: Rules and Metarules"; "Refractive Images: A World at Large".

These lectures were published as The Politics of the Family (1971). In the book Laing argued that the family unit had existed for at least 100,000 years but it was a very difficult subject to study. "We can study directly only a minute slice of the family chain; three generations, if we are lucky. Even studies of three generations are rare. What patterns can we hope to find, when we are restricted to three out of at least four thousand generations?"

R. D. Laing, published Conversations with Children (1978). The book was based on conversations with his own children. It received very poor reviews and the "common criticism levelled against him was that he who had so extravagantly exposed the family for the madness it caused was now living a bourgeois lifestyle, producing books not on the terrifying interiors of family life, but having the temerity to produce snippets of conversation with his own children."

The book sold very badly. So did other books produced during this period including The Facts of Life, Do You Love Me? An Entertainment in Conversation and Verse and Sonnets. This was a serious problem for someone who now had very expensive tastes. "He owned an enormous house, enjoyed travelling and eating out, had seven children, three of whom were still at school, and was living in middle-class comfort."

In 1982 R. D. Laing published The Voice of Experience: Experience, Science and Psychiatry, which "he hoped and believed would re-establish his rightful position among European intellectuals". Unfortunately this did not happen and it was only in Germany that the book was taken seriously. Laing argues in the book that natural science has rendered 'experience' outside its domain of investigative competence, and therefore of no value.

As Laing points out: "Love and hate, joy and sorrow, misery and happiness, pleasure and pain, right and wrong, purpose, meaning, hope, courage, despair, God, heaven and hell, grace, sin, salvation, damnation, enlightenment, wisdom, compassion, evil, envy, malice, generosity, camaraderie and everything, in fact, that makes life worth living. The natural scientist finds none of these things. Of course not! You cannot buy a camel in a donkey market."