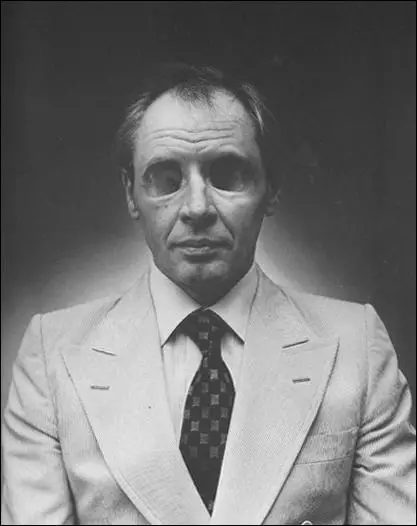

R. D. Laing

Ronald David Laing (usually known as R.D. Laing) was born in the Govanhill district of Glasgow on 7th October 1927, the only child of civil engineer David Laing and Amelia Kirkwood Laing. Laing later told Bob Mullan that his mother became pregnant after nine years of marriage and his mother's pregnancy was shrouded in mystery: "Amelia disguised the impending event by wearing a large overcoat. The thought that people would realise she had been sexually active with her husband appalled her." (1)

David Laing was an electrical engineer employed by the Glasgow Corporation. He was fairly well paid and the family had a reasonably good standard of living. There was "a piano and sufficient food and clothing for the Laings to consider themselves one up from the working classes who lived their lives toiling at the nearby tramworks or down at the shipyards." (2)

Amelia Laing dominated both her husband and her son. Her neighbours considered her to be "somewhat odd, if not actually psychiatrically ill". She was rarely seen outdoors and had a fear that people were spying on her. Amelia became increasingly possessive of her young son. Laing's biographer, Daniel Burston, claims that a "weaker or less self-possessed child" would have suffered some sort of developmental retardation as a result of his upbringing. (3)

Laing later claimed that despite this possessiveness, "she rarely cuddled or even touched him". Laing shared a bedroom with his mother "she sleeping alone in a double bed while his father was exiled to a room at the rear of the apartment". According to Laing his parents had almost no "emotional, sexual and social life" together. She also had a tendency to speak badly of her husband. (4)

Laing later recalled his feelings for his father. "I have feared, loathed and despised him" but later years "I have come to love, respect, admire and honour him. I feel very sorry for the travail he has had to undergo, but he seldom entirely lost his sense of humour, and then he could be awful. But I can never remember him being spiteful (expect once maybe), and not revengeful. He was not a perfect saint, I don't think, but he was basically a holy man, although he would have been very embarrassed had he thought I held such an opinion of him." (5)

Laing found school an escape from home and family life. At Sir John Neilson Cuthbertsons Primary School he was an outstanding student and in 1936 he won a scholarship to Hutchesons Grammar School where he was profoundly influenced by his study of the classics. Like his father he was a talented musician and his parents insisted that he spent several hours a day practicing on the piano. (6)

Amelia Laing was a member of the Covenanters, a Scottish Presbyterian movement. Ronnie was sent to meetings of the Scripture Union run by a man called Michael John. At the age of 14 he made his break with the Convenanters about "the word of God, Jesus dying on the cross, the Resurrection, sinfulness, the evils of cinema-going and - the most evil sin of all - physical contact with girls... even ballroom dancing was claimed to be the work of the devil by virtue of the possible physical contact between the male and female genitals (albeit with the superficial protection of the clothing)." (7)

R. D. Laing: Medical Student

Laing joined the Govanhill Library he worked his way through the philosophy section in alphabetical order. At the same time he worked his way through the entire Dictionary of National Biography. By the age of 15 he had explored the ideas of Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung, Søren Kierkegaard and Jean-Paul Sartre. (8) Laing claimed that he was especially attracted to Kierkegaard, and once read non-stop over a period of some thirty four hours, his Concluding Unscientific Postscript. (9)

There was a family debate about whether he should pursue a musical career. Eventually his parents came to the conclusion that he was not good enough to risk everything on such a perilous course. He therefore decided to go to Glasgow University to study medicine: "It was one of the things approved by my parents, and to me it offered entry into the secret rituals of birth and death... Besides there seemed no point in studying anything that was really important, like philosophy or psychology in a University curriculum." (10)

In 1948 he read an article by Antonin Artaud in Horizon: A Review of Literature and Art, on the artist Vincent Van Gogh, entitled Van Gogh, the Suicide Provoked by Society. Artaud argues that Van Gogh was the victim of a society unable to cope with creativity. He was described as an "authentic lunatic", that is, "a man who has preferred to become what is socially understood as mad rather than forfeit a certain superior idea of human honour. Van Gogh "was a man whom society has not wished to listen to, and whom it is determined to prevent from uttering unbearable truths." Artaud adds that "the cut-off ear was straightforward logic. I repeat: a world which every day and night increasingly eats the uneatable in order to adapt its bad faith to its own ends is forced, as far as this bad faith is concerned, to keep it under lock and key." In his later writings, R. D. Laing explored the links between creativity and mental illness. (11)

At university he developed an interest in psychology and attended extra-curricular lectures provided by Dr Isaac Sclare on Saturday morning. He also joined the Medico-Chirurgical Society and joined their annual visit to Gartnavel Mental Hospital. It provided him with his first encounter with the type of behaviour that obsessed him throughout his adult life. In June 1949, the university medical journal published his article, Philosophy and Medicine. He was also awarded the Medical Student's Prize of £25 for his essay Health and Happiness. (12)

In his fourth year Laing studied obstetrics. He was expected to deliver babies, sometimes on his own. One morning "on a clear August morning", a woman gave birth to a "grey, slimy, cold... a large human frog... an anencephalic monster, no neck, no head, with eyes, nose, froggy mouth, long arms". He wrapped the baby in newspaper with the intention of taking it to the pathology laboratory. Instead he spent the next two hours walking the streets with this bundle under his arm. He later recalled: "I needed a drink. I went into a pub, put the bundle on the bar. Suddenly the desire, to unwrap it, hold it up for all to see, a ghastly Gorgon's head, to turn the world to stone." (13)

However, his interest in philosophy and psychology meant that he did not spend much time on his official courses and he failed his exams. While waiting to resit his exams, he worked as a houseman in the psychiatric unit at Stobhill Hospital in Glasgow where he was employed on a full-time half-salary basis. It was here he met Aaron Esterson, who later became his co-researcher. He re-sat and passed his exams in December 1950 and graduated on 14th February, 1951. (14)

Neurosurgical Unit at Killearn

Laing's first post was at the West of Scotland Neurosurgical Unit at Killearn. Most of the patients were the victims of motoring accidents. In some cases the doctors performed lobotomies on the patients. This was an operation that involved severing connections in the brain's prefrontal lobe. Laing was totally opposed to this operation as he believed that a "lobotomy was the final act in the destruction of the will of the subversive, as drastic and inhumane as ever conceived by man against man". (15)

R. D. Laing became very close to a fellow student, Marcelle Vincent, who lived in Annecy, France. After they both graduated they planned to work with Karl Jaspers at the Neuropsychiatric Department of the University of Basel. Jaspers studied patients in detail, giving biographical information about the patients as well as notes on how the patients themselves felt about their symptoms. This has become known as the biographical method. He was unable to take up this post as he was drafted into National Service and enrolled into the Royal Army Medical Corps and sent to the British Army psychiatric unit at the Royal Victoria Hospital at Netley. (16)

At the hospital the doctors routinely used insulin comas on patients. "Insulin was administered at six o'clock in the morning and within four hours the patients began to go into coma. The course of insulin started off with ten units, increased daily by ten units until the patients went into deep comas and sometimes epileptic fits. The policy was to put it in at a level at which epileptic fits were liable to occur, but to avoid them if possible. Backs could break. Light is extremely epileptogenic under a lot of insulin. The ward was entirely blacked out. When people started to go into a coma we, the staff, moved around in total darkness, penetrated only by the rays of the torches on hinges we had strapped to our foreheads. It was essential to get each patient out of his or her coma before too long, because if we did not, the coma became 'irreversible'. Around ten o'clock, we poured quantities of 50 per cent glucose into the patients through stomach tubes. We hoped we had got the tube into the stomach rather than the lungs." (17)

The theory behind this treatment was that the patients would then be free of the inhibitions which previously prevented them from remembering and talking about themselves. This crude attempt to "rebirth" patients, by taking them to the edge in order to bring them back mentally cleansed, appalled Laing, as he considered it as inhumane treatment. He also thought it counter-productive as he believed that what was being "washed out" might contain "encoded messages that ought to be heard and deciphered". (18)

Laing argued that ECT (electroconvulsive therapy) and insulin comas were administered to deaden the mind and reduce cognitive and thought processes. Laing believed that the doctors should be entering into a dialogue with their patients. They responded by claiming that these conservations would merely excite these deadened minds. Laing insisted that these so-called treatments were merely methods of "destroying people and driving people crazy if they were not so before, and crazier if they were". (19)

Laing became especially interested in a patient named "John" who believed he had retreated into madness: "In his life he has had virtually nothing of the things he had set his heart on; he is well aware that he is regarded as mad but he says that why should he not be: now he is anyone he wants to be: has anything he wants: does everything he likes: why should he return to a world where he is unable to satisfy every one of his fundamental desires? Why indeed I find it very difficult to give him an answer. Insanity, suicide or sanity." (20)

Laing tried another approach to treating these patients. Influenced by the work of Harry Stack Sullivan, he sat with schizophrenics ''quietly... in their padded cells, a move construed by his superiors as dedicated research.'' (21) Like Sigmund Freud, Laing questioned the "traditional neurobiological view of schizophrenia and other disorders, but, like Sullivan, he was looking for sources in real rather than in fantasized quarters". (22)

Laing was also aware of the theories of Erich Fromm and Wilhelm Reich who described themselves as followers of Karl Marx. He agreed about the economic factors in mental illness and criminality: "My present work does not concern 'treating' these people - and in fact I am convinced that the only `treatment' is prevention. There are numerous statistical surveys which make it pretty clear that poor, insecure economic conditions, unhappy home life (e.g., parents drunk and quarrelsome), low education standard associated with under-average intelligence, and a number of other factors, are almost constantly present in those people who commit crimes at an early age." (23)

While working at Netley he began an affair with Anne Hearne, a nursing sister at the hospital. Soon afterwards he was promoted to the rank of captain and posted to the Catterick Military Hospital. Laing intended to move to France to be with Marcelle Vincent, when he finished National Service. However, his plans changed after he discovered Anne was six-months pregnant. The couple were married on 11th October, 1952. Laing's parents did not attend the wedding and after this he rarely saw them. It was later claimed that his mother made a "Ronald doll" and stuck pins in it in order to "induce a heart attack." (24)

Laing's daughter, Fiona, was born on 7th December. He left the army in September, 1953. On 18th May, 1953, he wrote in his diary: "Almost finished national service - 4 months to go. What have I achieved? F*** all. Yet I now have a baby girl, I am married, I own a flat, a great deal of piss has been knocked out of me, I have retained my friends, I have done perhaps inestimable harm to one person, I have become more reconciled with my parents, I have been forced to my knees, forced back to the Bible, Plato, Kant. I can hardly say that I have furthered my career." (25)

Gartnavel Royal Mental Hospital

After leaving the army Laing worked at the Gartnavel Mental Hospital. His main task was to treat over sixty women in the female refractory ward. ECT and insulin comas were the main forms of treatment. Some of the women had suffered lobotomies. Completely institutionalised, many of them manifested the behaviour they believed was expected of them, hearing voices and talking to themselves. After three months he proposed an experiment to the hospital authorities. He asked if he could carry out an experiment with twelve schizophrenic patients who had not endured a lobotomy and only a minimum of ECT. A person suffering from schizophrenia cannot understand what is real and what is imaginary who often experience delusions and hallucinations. They also display, disorganised speech, a loss of emotional responsiveness and extreme apathy. Laing was allowed to set up a ''Rumpus Room'' for mentally ill women that "allowed them some possibility for social interaction." (26)

Laing insisted that nurses should not wear uniforms and patients were encouraged to take a pride in their appearance. Laing received a disappointing response on the first day, but the second day saw a significant development. "An hour before the door was due to be opened, the woman were laughing, talking and fidgeting outside of it, eager to get inside. Laing later recalled the moment as one of the most moving of his entire life. These distressed, disturbed and incarcerated women were, for the first time, being treated like other human beings." (27)

Laing wrote about the experiment in the medical journal, Lancet: "In the last twelve months many changes occurred in these patients. They were no longer social isolates. Their conduct became more social, and they undertook tasks which were of more value in their small community. Their appearance and interest in themselves improved as they took a greater interest in those around them.... We started this work with the idea of giving patients and nurses the opportunity to develop interpersonal relationships of reasonably enduring nature. A physical environment was supplied which was clean and pleasant: and materials for knitting, sewing and drawing, a gramophone, foodstuffs, and facilities for cooking were made available, and the patients and nurses were left to make what use of them they wished. But our observations on the results seem to us to support the view that what matters most in the patient's environment is the people in it. The nurses found it useless merely to try to get the patients to do something; but, once the patients liked the nurses, attempts to help them became the basis for apparently autonomous activity in which the patients used the material in the environment."

Laing went on to point out: "The material used or the nature of the activity was of secondary importance. Some of the patients improved while they scrubbed floors; others baked, made rugs, or drew pictures. We conclude that the physical material in the environment, while useful, was not the most important factor in producing the change. It was the nurses. And the most important thing about the nurses, and other people in the environment, is how they feel towards their patients. Our experiment has shown, we think, that the barrier between patients and staff is not erected solely by the patients but is a mutual construction. The removal of this barrier is a mutual activity." Within eighteen months after the beginning of the experiment all twelve women had been discharged from the hospital, yet within a year all had returned to the institution. (28)

Tavistock Clinic

In 1956 Laing was appointed a senior registrar at the Tavistock Clinic. He was also seconded to the Institute of Psychoanalysis and as well as attending lectures and seminars, he ran a psychoanalytic clinic five times a week. Laing had a difficult relationship with John Bowlby who he found cold and dispassionate. According to Bob Mullan: "He abhorred the notion that without the right kind of maternal care someone was destined for mental ill-health. He saw it as a terrible condemnation of those who had suffered from a poor childhood - as if they hadn't enough to cope with." He was also unimpressed with Melanie Klein, Donald Winnicott and Wilfred R. Bion because "he found their teaching often didactic and authoritarian, and devoid of a sense of humour." (29)

Laing agreed to be analysed five times a week by Charles Rycroft. These sessions lasted for fifty minutes and went on for over four years. One problem was that Laing spoke with a thick Glaswegian accent which Rycroft found difficult to understand. It was claimed that "Ronnie undoubtedly saw Rycroft as an intellectual inferior (as he did with everybody) and an Englishmen to boot. He treated the whole time-consuming process as a necessary hassle in order to gain his badge as a psychoanalyst." (30)

Laing's graduation from the Institute of Psycho-Analysis was questioned by Fanny Wride and Isle Hellman as representatives of the British Psycho-Analytical Society. They argued that they were opposed to the idea that someone with Laing's temperament should be allowed to call himself a psychoanalyst: "So far as Dr Laing's actual knowledge and clinical work was concerned, the interviewers, so far as they were able to judge, thought that no useful purpose could be served by delaying Dr Laing's qualification. They were worried, however, by the fact that Dr Laing is apparently a very disturbed and ill person and wondered what the effect of this obvious disturbance would be on patients he would have to interview." (31)

R. D. Laing: The Divided Self (1960)

Laing completed The Divided Self by 1957, but it was turned down by a dozen publishers. It was finally published by Tavistock Publications in 1960. The book sold very badly and was not reviewed by the specialist press. (32) The clinical evidence for the book emerged out of his work at the British Army psychiatric unit at the Royal Victoria Hospital at Netley and at the Gartnavel Royal Mental Hospital. Laing claimed that the basic purpose of the book was to make madness, and the process of going mad, comprehensible. "The kernel of the schizophrenic's experience of himself must remain incomprehensible to us. As long as we are sane and he is insane, it will remain so. But comprehension as an effort to reach and grasp him, while remaining within our own world and judging him by our own categories whereby he inevitably falls short, is not what the schizophrenic either wants or requires. We have to recognise all the time his distinctiveness and differentness, his separateness and loneliness and despair." (33)

In the book Laing questioned the definition of madness: "In the context of our present pervasive madness that we call normality, sanity, freedom, all our frames of references are ambiguous and equivocal.... A little girl of seventeen in a mental hospital told me she was terrified because the Atom Bomb was inside her. That is a delusion. The statesmen of the world who boast and threaten that they have Doomsday weapons are far more dangerous, and far more estranged from 'reality' than many of the people on whom the label ‘psychotic' is affixed."

Laing adds: "Psychiatry could be, and some psychiatrists are, on the side of transcendence, of genuine freedom, and of true human growth. But psychiatry can so easily be a technique of brainwashing, of inducing behaviour that is adjusted, by (preferably) non-injurious torture. In the best places, where straitjackets are abolished, doors are unlocked, leucotomies largely forgone, these can be replaced by more subtle lobotomies and tranquillizers that place the bars of Bedlam and the locked doors inside the patient. Thus I would wish to emphasize that our 'normal' 'adjusted' state is too often the abdication of ecstasy, the betrayal of our true potentialities, that many of us are only too successful in acquiring a false self to adapt to false realities." (34)

In the book Laing attempted to explain what he meant by the term divided-self: "Self-consciousness, as the term is ordinarily used, implies two things: an awareness of oneself by oneself, and an awareness of oneself as an object of someone else's observation. These two forms of awareness of the self, as an object in one's own eyes and as an object in the other's eyes, are closely related to each other. In the schizoid individual both are enhanced and both assume a somewhat compulsive nature. The schizoid individual is frequently tormented by the compulsive nature of his awareness of his own processes, and also by the equally compulsive nature of his sense of his body as an object in the world of others. The heightened sense of being always seen, or at any rate of being always potentially seeable, may be principally referable to the body, but the preoccupation with being seeable may be condensed with the idea of the mental self being penetrable, and vulnerable. (35)

The central concept for Laing is that of ontological insecurity. An ontologically secure person will encounter the hazards of life from a "centrally firm sense of his own and other people's reality and identity". According to one interpretation of this concept: "An ontologically insecure person suffers a fundamental insecurity of being, an insecurity that pervades all of his existence. He is thereby forced into a continuous struggle to maintain a sense of his own being... The individual's total self, the 'embodied self', faced with disadvantageous conditions, may be split into two parts, a disembodied 'inner self', felt by the person to be the real part of himself, and a 'false self', embodied but dead and futile, which puts up a front of conformity to the world." (36)

In the book he uses the case of "Julie", who had been admitted to Gartnavel Royal Mental Hospital at the age of 17. She became one of Laing's patients nine years later. She had been labelled as being "a typical inaccessible and withdrawn chronic schizophrenic". Julie was mostly mute but when she did speak it was in 'schizophrenese'. After interviewing her close relatives, Laing concluded that Julie came from a close, loving family. She had an older married sister and an almost "doting mother". However, Julie told Laing that she believed that "her mother was trying to kill her". (37)

On one occasion Julie claimed that she "was born under a black sun". Laing was puzzled by this comment: "Julie had left school at fourteen, had read very little, and was not particularly clever. It was extremely unlikely that she would have come across any reference to it." Laing believed that she was expressing herself in a kind of poetry: “I was born under a black sun. I wasn't born, I was crushed out. It's not one of those things you get over like that. I wasn't mothered I was smothered. She wasn't a mother. I'm choosy who I have for a mother. Stop it. Stop it. She's killing me. She's cutting out my tongue. I'm rotten, base. I'm wicked. I'm wasted time." (38)

Julie always insisted that her mother had never wanted her, and "had crushed her out in some monstrous way rather than give birth to her normally". Her mother had "wanted and not wanted" a son. Julie was "an accidental son whom her mother out of hate had turned into a girl. The rays of the black sun scorched and shrivelled her. Under the black sun she existed as a dead thing.... She's the ghost of the weed garden. In this death there was no hope, no future, no possibility. Everything had happened. There was no pleasure, no source of possible satisfaction or possible gratification, for the world was as empty and dead as she was... She was utterly pointless and worthless. She could not believe in the possibility of love anywhere." (39)

Richard Sennett argued in the New York Times that Laing had been influenced by the work of Gregory Bateson: "The book's power lay in Laing's ability to catch the rationality behind seemingly irrational behavior, a logic he revealed by making the reader see through the eyes of someone labeled schizophrenic. Laing did not 'explain' schizophrenia as a disease; he showed how schizophrenia was a perfectly logical way of coping with impossible, longstanding situations in a person's family or immediate society. Much of this ground was prepared for Laing by the American anthropologist Gregory Bateson - probably one of the greatest and most neglected writers on human behavior in this country." (40)

Experiments with LSD

In 1961, while he was still employed by the Tavistock Clinic, Laing established a private practice in Wimpole Street. In his consulting room, chairs were scattered at random creating a more relaxed and less orthodox atmosphere. Laing began to experiment with LSD, both on himself and with consenting patients. Laing became convinced that by using this drug he was able to re-experience the sensations he might well have enjoyed as a young boy, in which new perspectives would unfold and reveal themselves to him. (41)

Laing read the work of Aldous Huxley who had written about his own experiences with LSD, mescaline and peyote, in his book, The Doors of Perception (1954). Huxley argued that it was possible to use these psychedelic drugs to enable the mind's awareness to be expanded to new horizons. Huxley compared the visionary psychedelic experience experiences with that of the schizophrenic experience and argued that both have times of "heavenly happiness". However, Huxley concluded that, unlike the mescaline taker, schizophrenics do not know when, if ever, they will be "permitted to return to the reassuring banality of everyday experiences". Huxley added: "Sanity is a matter of degree and there are plenty of visionaries... who grind out guilt and punishment, solitude and unreality... but contrive, none the less, to live outside the asylum." (42)

Laing was given permission by the British government, through the Home Office, to use LSD in his treatment of patients. LSD at this time was being manufactured in Czechoslovakia. Laing preferred to take a small amount of LSD (administered in diluted form in a glass of water) with the patient, and for the session to last not less than six hours. Some patients found taking the drug as both "exhilarating and liberating" and argued that a single six-hour LSD session could be more beneficial than years and years of orthodox psychoanalysis. "For others the experience could prove too much too soon." (43)

R. D. Laing explained at a conference: "An LSD or mescaline session in one person, with one set in one setting may occasion a psychotic experience. Another person, with a different set and different setting, may experience a period of super-sanity… The aim of therapy will be to enhance consciousness rather than to diminish it. Drugs of choice, if any are to be used, will be predominantly consciousness expanding drugs, rather than consciousness constrictors – the psychic energisers, not the tranquillisers." (44)

Laing admitted by 1965 he had conducted over one hundred therapeutic LSD sessions. One of his patients, Mina Semyon, returned to her childhood after taking the drug: "I found myself sitting on the floor curled up in a little ball, in a damp cold room in the Tartar Republic. I am four years old, my father is dead, my mother is lying in bed with covers over her head crying, and the Tartar landlady, whose son was just killed in the war, was lying behind the Russian oven wailing. I am sitting with shoulders hunched, sandwiched between their grief, my dress feels cold and damp, almost standing up, I am feeling a nobody, not considered, beaten down by life and abandoned." (45)

Another patient pointed out: "My own experiences taking LSD on a therapeutic basis were less enjoyable and far less enlightening, somewhat low key yet desperately disturbing. On each of the four occasions, my head quickly lost its shape and possessed no firm parameters. It was as if it could have floated away from my neck at any given moment. Soon afterwards, each time, I appeared to turn into an orange. Particularly distressing was the sensation of a hidden hand attempting to peel my skin." (46)

Laing continued to campaign against lobotomies and ECT treatments. He wrote in The British Medical Journal: "Twenty male and 22 female schizophrenics were treated by conjoint family and milieu therapy in two mental hospitals with reduced use of tranquillizers. No individual psychotherapy was given. None of the so-called shock treatments were used, nor was leucotomy. All patients were discharged within one year of admission. The average length of stay was three months. Seventeen per cent. were readmitted within a year of discharge. Seventy per cent of the others were sufficiently well adjusted socially to be able to earn their living for the whole of the year after discharge. These results are the first to be reported on the outcome of purely family and milieu therapy schizophrenics, and they appear to us to establish at least a prima facie case for radical revision of the therapeutic strategy employed in most psychiatric units in relation to the schizophrenic and his family. This revision is in line with current developments in social psychiatry in this country." (47)

R. D. Laing: Sanity, Madness and the Family (1964)

Laing joined forces with Aaron Esterson to publish Sanity, Madness and the Family (1964). This research project included one hundred female schizophrenics and their families. Once the patient and her parents and other family members had agreed to participate, Laing and Esterson conducted interviews with the patient alone, then together with the other family members, and then finally alone with her parents. All the interviews were recorded and subsequently transcribed. (48)

One of the case studies involved the seventeen year old Ruby Eden who was originally admitted to hospital in an inaccessible catatonic stupor. She had recently had an unwanted pregnancy and subsequent miscarriage. She complained of hearing voices, calling her "slut", "dirty" and "prostitute". Ruby was also convinced that her family disliked her and wanted to get rid of her. In 22 hours of interviews with Ruby and her family uncovered a "miasma of deceit" concerning the relationships between family members. Laing commented that "the most intricate splits and denials in her perception of herself and others were simultaneously expected of this girl and practised by the others". (49)

Ruby was the illegitimate offspring of a liason between her mother and a married man who visited occasionally, whom Ruby called "uncle". Cast out by her own father, Ruby's mother was given sanctuary by her own sister and her brother-in-law whom Ruby was encouraged to call "daddy". Ruby was told about her illegitimacy and her mother's attempts to abort her. Laing argues that the main problem is the physical attraction that Ruby shows towards her uncle: "She won't leave me in peace - she's always stroking me, pawing me... I won't pamper like her mother and aunt. If I pampered her she'd stop pawing me but I don't." (50)

Ruby believes that the neighbours are highly critical of her behaviour. Her mother rejects this idea: "They are so kind to her. They're all interested in her welfare. No one has said a word to her about it or going into hospital, not a word, there's no gossip. I don't know what Ruby should think the neighbours are talking about her." Her aunt agrees: "Nobody's ever been unkind to her... Ruby is the one who can't keep things to herself. She'll tell everyone her business." (51)

R. D. Laing argued that the claustrophobic nature of many of the families suggests a "form of subtle emotional blackmail, a killing by kindness". This makes daughters feel restricted, with no life of their own and unable to healthily separate from their parents. (52) In the book, Laing maintained that "schizophrenia was a strategy which a person invented in order to live in an unlivable situation". (53)

Philadelphia Association

Laing would meet with a group of friends every Friday evening to discuss philosophical issues. This included David Cooper, Aaron Esterson, Clancy Sigal, Joan Cunnold and Sidney Briskin. They discussed the possibility of creating a residential community, "based on the principles of the Iona Community - a requirement that time should be spent each day in study and prayer, the willingness to make personal economic and emotional sacrifices for the sake of the well-being of the community, acceptance of the need to spend time in recreation and with one's family, the need for regular meetings, and the pledge to work for peace at national and international levels." (54)

As a result of these discussions Laing established the Philadelphia Association, "concerned with the understanding and relief of mental suffering." (55) In June, 1965, Kingsley Hall, a community centre, at Bromley-by-Bow in the East End of London, was used as the group's residential centre. The aim of the experiment was to create a model for non-restraining, non-drug therapies for those people seriously affected by schizophrenia. The group believed that "mental suffering, including schizophrenia, was not to be seen as inevitably caused by biological, neurological or genetic factors, but rather as a response to interpersonal and social, as well as existential factors, and that 'natural healing' might well take place given time and the right circumstances." (56)

Mary Barnes, a trained nurse, who was diagnosed a schizophrenic and undergone electro-convulsive therapy and insulin treatment, became Kingsley Hall's first patient and underwent regression therapy. With the help of her psychotherapist Dr Joseph Berke, who provided coloured crayons and encouraged her to paint with her fingers, Mary Barnes's spirit gradually returned. She took to painting fanatically, covering enormous canvasses with images from religion and nature. Her canvases were first shown in 1969 at the Camden Arts Centre in London. (57)

R. D. Laing lived in Kingsley Hall until the end of 1966 when he moved to an apartment in Belsize Park Gardens. Dr. Berke eventually took more responsibility for Kingsley Hall but Laing continued to play an important role in what he considered to be a successful experiment: "People lived there who would have been living nowhere else - except in a mental hospital - who were not on drugs, not getting electric shocks or anything else, who came and went as they pleased. There were no suicides, there were no murders, no one died there, no one killed anyone there, no one got pregnant there." (58)

In its first five years Kingsley Hall admitted over one hundred and twenty people, with an average stay of something like three months, though other residents stayed over four years. However, it received a lot of bad publicity and local condemnation. This included false rumours that Laing was always on LSD and that he was sleeping with the women residents. This experiment came to an end when the lease expired in 1970. (59)

R. D. Laing: The Politics of Experience and the Bird of Paradise (1967)

The publication of Sanity, Madness and the Family brought him to the attention of the wider public. In 1964 Laing appeared on UK television on five occasions. He wrote in his diary: "I feel I am going to become famous, and receive recognition. Most of my work has not hit the public yet, eventually it will, like the light from a dead star". (60)

In November 1964, he published an article in the New Left Review entitled "What is Schizophrenia?". He argued that "I do not myself believe that there is any such 'condition' as 'schizophrenia'. Yet the label as social fact, is a political event. This political event, occurring in the civic order of society, imposes definitions and consequences on the labelled person. It is a social prescription that rationalizes a set of social actions whereby the labelled person is annexed by others, who are legally sanctioned, medically empowered, and morally obliged, to become responsible for the person labelled... After being subjected to a degradation ceremonial known as psychiatric examination he is bereft on his civil liberties in being imprisoned in a total institution known as a 'mental hospital'. More completely, more radically than anywhere else in our society he is invalidated as a human being." (61)

In 1965 a paperback version of The Divided Self was published. This created a sensation and over the next few years it sold over 700,000 copies and was translated into nearly every language spoken throughout the world including Arabic, Hebrew and Japanese. As one of his biographers, Charles Rycroft, pointed out: "This idea that schizophrenics and, by extension, neurotics are victims, the damaged but heroic survivors of impossible inhuman family and social pressures, was, coupled with Laing's charm and literary skill, largely responsible for the fact that he became a leading cult figure of the counter-culture of the 1960s." (62)

The Politics of Experience and the Bird of Paradise was published in 1967. It was a collection of lectures that had been delivered over the last five years. The material "provided a unified philosophical perspective on the nature of madness", which owed more to his studies of Karl Marx, Jean-Paul Sartre and Friedrich Nietzsche than any clinical work on psychiatry. (63)

Laing upset the medical profession when he argued that psychiatrists could give little help to people who were suffering from mental illness. In fact, they could do a great deal of harm: "Many patients in their innocence continue to flock for help to psychiatrists who honestly feel they are giving people what they ask for: relief from suffering. This is but one example of the diametric irrationality of much of our social scene. The exact opposite is achieved to what is intended. Doctors in all ages have made fortunes by killing their patients by means of their cures. The difference in psychiatry is that it is the death of the soul." (64)

Laing also illustrated the role in the family in mental health problems: "The Family's function is to repress Eros: to induce a false consciousness of security: to deny death by avoiding life: to cut off transcendence: to believe in God, not to experience the Void: to create, in short one-dimensional man: to promote respect, conformity, obedience: to con children out of play: to induce a fear of failure: to promote a respect for work: to promote a respect for respectability". (65)

The book was "the fulsome and unrestrained attack on almost every conceivable social institution including the family, psychiatric hospitals, the church, schools and the educational system, political and scientific organisations and, of course, the processes of conformity and so-called 'normality'. His language was angry, violent, political and apocalyptic." (66)

Laing pointed out: "A child born today in the UK stands a ten times greater chance of being admitted to a mental hospital than to a university, and about one fifth of mental hospital admissions are diagnosed schizophrenic. This can be taken as an indication that we are driving our children mad more effectively than we are genuinely educating them. Perhaps it is our very way of educating them that is driving them mad." (67)

Laing rejected the idea of Karl Marx that alienation was a consequence of the economic system: "We are bemused and crazed creatures, strangers to our true selves, to one another, and to the spiritual and material world - mad, even, from an ideal standpoint we can glimpse but not adopt. We are born into a world where alienation awaits us. We are potentially men, but are in an alienated state, and this state is not simply a natural system. Alienation as our present destiny is achieved only by outrageous violence perpetrated by human beings on human beings." (68)

Bob Mullan argues that "perhaps the most controversial statement that Laing made, certainly as far as orthodox psychiatry was concerned" was the claim that "madness need not be all breakdown, it may also be break-through... it is potentially liberation and renewal as well as enslavement and existential death." Mullan defends him by claiming that Laing is quite simply stating the obvious: some individuals suffer the experience of madness and reemerge somewhat the wiser, although many do not and suffer interminable existential death instead." (69) However, this defence of Laing is undermined when he concludes the chapter with a remark aimed at conventional psychiatry. Laing admits that "because they are humane, and concerned, and even love us, and are very frightened, they will try to cure us. They may succeed. But there is still hope that they will fail." (70)

The Politics of Experience and the Bird of Paradise received a hostile reception from the profession. The review in the British Journal of Psychiatry commented: "Surely the young people who turn to Laing for help deserve to know what he is wearing, what role he offers them, what model he uses, what authority he speaks from. In this book, he offers three models which can be disentangled only with the greatest difficulty. None of them is the medical model, from which we believe he derived his authority. If Laing wishes to be a guru or a philosopher, there is no doubt a place for him, but young people who are suffering from schizophrenia may prefer to entrust themselves to a doctor who will treat their illness as best he can." (71)

Richard Sennett wrote in the New York Times that he was very disappointed by Laing's political development. "By the time Laing wrote The Politics of Experience (1967), it seemed logical that he would become a social analyst, a man whose experience as a psychiatrist would give him, and his readers, new insights into how society organized repression. But these insights were not forthcoming. Rather than follow the logic of his own anger and become a social critic, he chose to make his patients, whom he had formerly seen as dignified in their suffering, into heroes. He dealt with society only by clinging to those people who were its victims and whose actions, if not intentions, showed they were fighting back." (72)

Divorce and Marriage

Ronnie's relationship with Anne was "less than fulfilling, and at times excruciating painful." According to one source they "argued so loudly and ferociously that their neighbours complained". Laing began a relationship with the journalist Sally Vincent, who found Laing "endearingly and emotionally very expressive, and that he would unselfconsciously burst into tears at the cinema or theatre". However, she also found that "at times he could be brutally frank, and refused to provide either socially-expected answers or conversation". (73) Vincent admitted "Ronnie was brilliant, a complete original, but he desperately overdid the drugs and drink ... He would be lying on the floor, paralytic but talking nonstop and making perfect sense." However, she found Laing difficult to live with and eventually the relationship came to an end and he returned to Anne Laing. (74)

R. D. Laing then spent time in France where he resumed his relationship with Marcelle Vincent. She arranged for him to meet the French philosopher, Jean-Paul Sartre. The two men had a two-hour conversation about politics and philosophy. Laing argued that for Sartre, psychoanalysis is "above all an illumination of the present acts and experience of a person in terms of the way he has lived his family relationships". (75)

In 1965 Laing began living with his new young German girlfriend, Jutta Werner. The following year Anne Laing decided to take the five children to start a new life near La Gorra in the South of France. A lack of money forced them back to London. After a spell living in Devon with her parents, in September, 1966, Anne decided to settle in Scotland. Adrian Laing recalls that his father went to see his family two years later, "by which time I had forgotten what he looked like." (76)

John Clay, the author of R. D. Laing: A Divided Self (1996) has claimed that Laing "sent little money to support them". (77) Others like Bob Mullan, have defended his behaviour towards his wife and children. "However I believe, partly because he was a psychiatrist, and especially because he was one who wrote about the family, and partly because he ruffled many establishment feathers, he has been unfairly treated. At the least it can surely be agreed that from the outset his relationship with Anne was based on a sense of duty rather than reciprocal love, that the joint decision to bring further children into the world was a brave attempt at continuing a marriage that was doomed, and that their radically different lifestyles, skills and sensibilities invariably led to quite different expectations." (78)

In 1967 Jutta Laing gave birth to a son, Adam. This was followed in 1970 by Laing's seventh child, a girl whom they named Natasha. In March 1971, Ronnie, Jutta and the two children went to live in Sri Lanka. He took no books, no writing matter and no drugs. "He had waited all his life for a spiritual journey of this magnitude, and had no intention of compromising his high ideals." After leaving the rest of the family at the Bandarapola Tourist Lodge he joined a Buddhist meditation retreat in Kanduboda, where he stayed for six weeks. (79)

In September 1971, the family flew to Madras and then spent the next six months in India. This included Ronnie staying with a wise old man by the name of Gangotri Baba in the foothills of the Himalayas. He also visited another wise man by the name of Mufti Jal al-Ud-din and asked three questions: "What is man's chief end in life? 2. What is the correct way to live? 3. What is the method to rid oneself of the corruptions that defile the heart and weaken wisdom?". The wise man replied: "If you wish to help your fellow man there is no better way to do so than to give up the world, renounce everything and take up the robe and bowl." (80)

R. D. Laing told Israel Shenker, of the New York Times: "I spent a month up a mountain with an Indian holy man who lived under a rock cranny up a ravine. He had let his hair grow and spent much of the time naked. wrapped in his hair to keep warm. I sat with him all day, tuned in to the rhythm of daytime and night-time, watching the sun go down and the moon come up. The largest lessons I learned are ineffable and I don't even begin to put words to them... I was doing nothing all day except watching one's own bodily sensations. One's stomach got empty, one's colon got filled up, one's hunger rose up and abated. Food was one of my heaviest addictions, and it took a week to get out on the other side.” (81)

R. D. Laing, The Politics of the Family (1971)

In 1968 R. D. Laing was invited to provide a series of lectures in honour of Vincent Massey, the former Governor-General of Canada. The five lectures were broadcast on radio by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. The lectures were entitled: "The Family, Invalidation and the Clinical Conspiracy"; "Family Scenarios: Paradigms and Projection"; "The Family and the Sense of Reality"; "Beyond Repression: Rules and Metarules"; "Refractive Images: A World at Large". (82)

These lectures were published as The Politics of the Family (1971). In the book Laing argued that the family unit had existed for at least 100,000 years but it was a very difficult subject to study. "We can study directly only a minute slice of the family chain; three generations, if we are lucky. Even studies of three generations are rare. What patterns can we hope to find, when we are restricted to three out of at least four thousand generations?" (83)

Laing had used the methodology of detailed interviews with family members, but this had caused him considerable difficulties: "Maybe no one knows what is happening. However, one thing is often clear to an outsider: there is concerted family resistance to discovering what is going on, and there are complicated stratagems to keep everyone in the dark, and in the dark that they are in the dark. The truth has to to be extended to sustain a family image." (84)

Attempts to improve the situation often ends in failure because change is extremely difficult to facilitate: "The strategy of intervening in situations through the medium of words by telling people what we think they are doing, in the hope that thereby they will stop doing it, because we think that they should not be doing what we think they are doing, is frequently vastly irrelevant to all concerned." (85)

Richard Sennett, mounted a devastating attack on the book in the New York Times. Sennett acknowledged that in his early books he had provided some interesting insights into the problems facing society. "The writings of R. D. Laing have moved from early books which put forth a complex, painful vision of the human oppression involved in the phenomenon society labels 'insanity' to books which replay all the early themes in such a fashion that the reader feels he is in a closed and stuffy room."

Sennett goes on to argue that " Laing's thought has disintegrated dramatically in the last four years, but it is unworthy of him simply to itemize that decline. For what has happened to show why it is not just a matter of words that makes contemporary words of anger stale." However, like other members of the counter-culture "who took fire during the recent years of turbulence are now passing through a moment when a great number of painfully acquired ideas threaten to enter the comfortable landscape of cliché... Laing has substituted an easy rhetoric of accusation and condemnation for the struggle to understand people's feelings that dignified his earlier work."

According to Sennett, Laing had been de-radicalised: "He is led by the force of his own sympathy to admire them, to want to be like these rebels, at least to champion them. As a a result, society seems ever less real apart from its effect on the lives of its victims, and the sympathizer's own life seems less real too; he orients his own reactions to society by those who are suffering so much more than he is... Blacks in the South and the urban ghettoes who were treated this way during the 1960's told their white friends to go home; the blacks felt used. Laing's sympathy for his mentally ill patients is enmeshed in the same contradictions that led to a crisis between black and white civil rights workers, but he has gone a step further. Laing has come to see madness not just as an act of rebellion, but as an act of 'liberation,' of 'waking up,' of a 'freeing' of the individual from society's constraints. Rebellion and liberation are separated by a simple matter of fact: a liberation ends the causes of the distress that makes people want to rebel. Laing, however, has turned this around, and looks at madness as a liberation in which the individual reorganizes the world on his or her own terms, so that society can be shut out." (86)

Lecture Tours

By 1972 Laing was exhausted. He was offered speaking engagements all over the world. He found the travelling tiring and did not enjoy lecturing and was often sick beforehand. Laing's own existing patients required attention and care. His fame also increased the demand from individuals who wished to receive analysis. More and more demands were made by the media who wanted to know his views on a wide range of different subjects. "In the USA he was expected to make pronouncements about Richard Nixon and Vietnam, and he also felt that there were widespread hopes that he would become a demagogue." (87)

R. D. Laing also began to question his achievements and found it difficult to find the energy to work and was suffering from "writers block". In May 1972 he wrote in his diary: "I've got to keep my nerve - or lose it - everything is completely uncertain. I've lost my motivations and beliefs - there is nothing I want to do and I don't want to do nothing. It's really like starting a new life and I would be just as glad not to…. I have depassed myself into a void." (88)

In November, 1972, he arrived in the United States for a five-week long lecture tour. His performances were often sold out and at Santa Monica he performed before 4,000 people, a week after Bob Dylan had pulled in the same number. It has been claimed "that many of his audience would touch him as he walked past them treating him like a prophet or a guru". He also appeared on television where he debated with Norman Mailer. However, Margaret Mead refused to appear with him because he had deserted his first family of five children. (89)

Laing's lectures did not always get good reviews in the press. Glenda Adams reported in the Village Voice following a session at Hunter College: "The house was sold out, and so had R. D. Laing. This revolutionary psychiatrist, friend of the so-called schizophrenic, who has opened the eyes of so many of us, entertained a house full of fans in what turned out to be a Dick Cavett Faith Healing Exercise. And R.D. was laughing at them as he pocketed their money... The dogma handed out that evening was: sitting cross-legged and barefoot on the floor for an hour was good; wearing glasses was bad; a stiff upper lip was bad; organic materials were good; living in New York was bad." (90)

Richard Sennett agreed with Adams about Laing's decline and compared him to revolutionary thinkers such as Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud: "Laing has lost that capacity to dream which is necessary in any enduring radical vision. Critics like Marx and Freud did not content themselves with saying justice would reign when the old abuses disappeared. Each of them tried to create a scenario for a just life that was greater than a mirror image of the old. For Marx, socialism ended the abuses of capitalism, but Communism instituted human relationships of a wholly new order. The acts of intelligence Freud called ego strengths were not compromises between the warring factions of instinct and external circumstance; they were creative powers to make new meanings, new satisfactions. Because Laing now has lost the power to dream and make his readers dream and desire, his catalogue of abuses is losing its power to anger." (91)

The most controversial incident of the tour took place in Chicago, when he was invited by a number of physicians to examine a young woman diagnosed as schizophrenic. "Naked, incarcerated in a padded cell, she rocked back and forth, seemingly in a world of her own. Laing was asked for both diagnosis and prognosis. To their surprise, he took off all his own clothes and joined her, rolling back and forth in her rhythm. A little later, a half hour or so, she spoke for the first time in several months." (92)

Reputation in Decline

R. D. Laing had very little contact with his first wife and their five children. One of his daughters, Susie Laing, appeared in a Sunday Times feature about the children of well-known individuals. During the interview she sadly pointed out that her father could "solve everybody else's problems, but not ours." (93) His biographer, John Clay, added that Laing's reaction to criticism was "to turn in on himself and start drinking in a self-destructive way" and it was "an irony that he, the expert on families, should fail so lamentably to relate to his own family." (94)

Another child, Max, was born on 24th June, 1975. Soon afterwards he was told that his daughter, Susie, who was only twenty-one and engaged to be married, was suffering from a terminal illness, lymphatic leukemia. Laing was furious when he discovered that she had not been told that she was dying: "I almost had to fight my way to the nursing sister. I went up one Sunday afternoon and decided I was going to tell her. She was in this oxygen tent permanently, hardly able to lift her head off the apparatus that circulated the blood... If you're disconnected from it you die in about three weeks maximum.... I just told her the facts, as I knew them, she was elected to be disconnected and taken back to her boyfriend's flat." (95)

Laing believed that the newly-born experienced as much pain as any adult, and that any painful memories of such pain would be stored up, to "resonate in later life". He agreed with Otto Rank that every birth was a "primal catastrophe". Rank believed that "even with the kindest of mothers and the least violent of births, the human being is born afraid, a shivering bundle of angst cast adrift in an uncaring world, a small island of pain floating on a vast ocean of indifference." (96)

Elizabeth Fehr was an American therapist who pioneered the idea of recreating the birth process as a means of dealing with an individual's mental health problems. Laing decided to orchestrate his own re-birthing sessions, with hundreds of participants. He described the procedure as including "birth-like experiences, yelling, groaning, screaming, writhing, contorting, biting, contending", in which a lot of "physical handling might ensure and a lot of energy" was released and redistributed. (97)

The theoretical ideas that he had developed in re-birthing, were published in the book The Facts of Life (1976). The book was "composed of seemingly unconnected essays on birth and pre-birth experiences and psychology, relentless critiques of conventional psychiatric practice, autobiographical memories and reflections, vignettes culled from his own clinical work and amusing observations on interpersonal communications as recalled from his own conversations and behaviour with others." (98) Geoffrey Gorer, writing in The Guardian argued that Laing "was a played out and damp squib, and there was nothing there in the first place." (99)

Laing's lectures were also criticised. It was a review in New Society that concentrated on his appearance that hurt him the most: "Laing... was dressed up with an almost excessive conservatism (to forestall medical criticism?): well-dressed suit, cuff-links, shiny black shoes, quiet tie, and socks that seemed held up by suspenders. His fellow associates were on a different wavelength: open shirts, fancy shoes, light-weight suits, beards. If clothes do make the person - or at least announce the person - there was a range here that Marks and Spencers could be proud of. Dress and let dress, is part of the message, too, perhaps." (100)

R. D. Laing also began to have doubts about what he had achieved. Laing admitted to his friend, Bob Mullan, that he had limited success in his work: "If you ask me what have I done or given to people, a lot of people who have come to see me have said that the main thing they have got from me is that I listen to them. They have actually found someone who actually heard what they are saying and listened... For many people in life, there's no one listening to them, no one hears them, no one sees them, they are made up by everyone, they feel quite rightly that they are ghosts. They might as well be dead, as far as their nearest and dearest are concerned... and ... so if they come to see someone who actually sees and hears them and actually recognises their reality, their existence, that in itself is liberating." (101)

On 21st April, 1978, Laing's father died, David aged eighty-five. He travelled to Glasgow for the funeral and managed not to argue with his mother during the ceremony. A few days later she sent him a letter requesting that he never ever visit her again, either before or after her death, and that he should not attend her funeral. Laing was told by his daughter that his mother made a doll, which she had christened Ronald, and into which she was sticking pins in order to give her son a heart-attack. (102)

Laing wrote in his diary: "The dead live through us. I feel in a way, his representative, in a way I never did as far as I remember, while he was alive. I often wondered how I would react to his death. One of the surprises is that I hadn't realized the extent to which I have incorporated him. I don't mind. I'm glad. I have feared, loathed and despised him. But, especially in the last ten years I have come to love, respect, admire and honour him. I feel very sorry for the travail he has had to undergo, but he seldom entirely lost his sense of humour, and then he could be awful. But I can never remember him being spiteful (expect once maybe), and not revengeful. He was not a perfect saint, I don't think, but he was basically a holy man, although he would have been very embarrassed had he thought I held such an opinion of him." (103)

R. D. Laing published Conversations with Children (1978). The book was based on conversations with his own children. It received very poor reviews and the "common criticism levelled against him was that he who had so extravagantly exposed the family for the madness it caused was now living a bourgeois lifestyle, producing books not on the terrifying interiors of family life, but having the temerity to produce snippets of conversation with his own children." (104)

The book sold very badly. So did other books produced during this period including The Facts of Life, Do You Love Me? An Entertainment in Conversation and Verse and Sonnets. This was a serious problem for someone who now had very expensive tastes. "He owned an enormous house, enjoyed travelling and eating out, had seven children, three of whom were still at school, and was living in middle-class comfort." (105)

In 1982 R. D. Laing published The Voice of Experience: Experience, Science and Psychiatry, which "he hoped and believed would re-establish his rightful position among European intellectuals". Unfortunately this did not happen and it was only in Germany that the book was taken seriously. Laing argues in the book that natural science has rendered 'experience' outside its domain of investigative competence, and therefore of no value. (106)

As Laing points out: "Love and hate, joy and sorrow, misery and happiness, pleasure and pain, right and wrong, purpose, meaning, hope, courage, despair, God, heaven and hell, grace, sin, salvation, damnation, enlightenment, wisdom, compassion, evil, envy, malice, generosity, camaraderie and everything, in fact, that makes life worth living. The natural scientist finds none of these things. Of course not! You cannot buy a camel in a donkey market." (107)

Laing developed a reputation as an aggressive alcoholic. Laurie Taylor met Laing for the first time in 1983: "I was mildly surprised to see him looking so well. When I had mentioned my intended visit to some colleagues, they had made remarks along the lines of him being 'past it'. One had even said in a casual voice that he rather thought Laing was dead.... But a little of my surprise was also occasioned by the nature of Laing's good health. His build suggests pugilism rather than asceticism and he still retains the sort of Scots accent which you feel would ensure healthy respect in a crowded bar." (108)

Although he remained married to Jutta Laing he continued to have affairs with other women. On 15th September 1984, Sue Sünkel, a German-born therapist, gave birth to Laing's ninth child and fifth son, Benjamin. He also began a sexual relationship with his secretary, Marguerite Romayne-Kendon. They moved in together and in 1986 Jutta divorced him. She was given custody of their children, and according to Laing she "received a generous financial settlement". (109)

On 27th November, 1984, he was charged with being in possession of 6.98 grams of cannabis resin. At first he wanted to plead guilty but was persuaded by his son, Adrian Laing, a lawyer, to admit the offence. In return, the court imposed a nominal sentence - a twelve month conditional discharge. However, Laing was far from pleased with his son's intervention: "By the end of the year Ronnie's behaviour was alienating almost everyone around him." (110)

In his next book, Wisdom, Madness and Folly: The Making of a Psychiatrist (1985), Laing argued that psychiatry is dissimilar to other branches of medicine as it treats people physically in the absence of any known physical pathology. "Mental hospitals and psychiatric units admit, routinely, every day of the week, people who are sent 'in' for non-criminal conduct, but for conduct which their nearest and dearest relatives, friends, colleagues and neighbours find insufferable. This is our society's only resolution to this unlivable impasse. If they refuse to go away, or can't or won't fend for themselves, it is our only way to keep people out of the company that can't stand them." (111)

According to Laing it is the only branch of medicine that treats people against their will if it deems necessary, even to the extent of imprisoning them should it consider such an action appropriate: "On the basis of possibly less than five minutes from the first laying on of eyes on a stranger, without that stranger perhaps even having moved or said anything (so: he is either malingering, or he is a mute catatonic schizophrenic), a psychiatrist can sign a printed form and make a phone call. This will be enough for that person to be taken away, imprisoned and observed indefinitely ... in involuntary custody, and then drugged, regimented, reconditioned, brain given electrical lavages, bits possibly taken out by knife or laser, and anything else the psychiatrist decides to try out." (112)

The book received bad reviews for the book. He was especially upset by a review by Carol Tavris in the New York Times in September, 1985, that had suggested: ''The reader acquainted with Dr. Laing will not learn here why he became disenchanted with his earlier ideas and abandoned the politics of madness, why his own methods of treating schizophrenics failed, or what he now believes about mental illness.'' (113) Laing wrote to the newspaper complaining "I want to put it on record that: (i) I have not become disenchanted with my earlier ideas; (ii) I have not abandoned the politics of madness; (iii) I do not regard my methods of treating schizophrenics as having failed." (114)

Tavris responded by suggesting "If Dr. Laing truly hasn't changed his mind, though, I would dearly love to know why - why, in light of so much research, he continues to hold ideas some 30 years old. But that's my point. The reader of his latest book won't have the foggiest idea of his current beliefs or their relation to his earlier controversial work." She then quoted from Elaine Showalter, who was about to publish her new book, The Female Malady: Women. Madness and English Culture, "even Laing became an anti-Laingian in the 1970s, nervously separating from left wing politics, drugs, mysticism, attacks on the family, even anti psychiatry…. This determined exit from all the political positions he had claimed in the 1960s came as a shock to Laing's supporters and critics both.'' (115)

Peter Hillmore, a former supporter of Laing joined in the attack. He interviewed him in March, 1985 and Laing said: “Life, you see, is a sexually transmitted disease and there's a 100 per cent mortality rate”. Hillmore commented: "If R.D. Laing had said that to me in the late Sixties/early Seventies, I would have immediately done two things: (1) I would have rushed away and told all my friends that the great guru had actually spoken to me, and (2) I would have pondered the meaning for ages and found deep significance in it.... When R.D. Laing said it to me last week, two completely different reactions were provoked: (1) I recalled having seen it as a piece of graffiti on a lavatory wall some months previously, and (2) I got to thinking what exactly did it mean? I relegated it to the meaningless and ponderous statements such as `Who digs deepest deepest digs' and `Never look for apple blossom on a Cherry tree.' I also wondered which one of us had changed." (116)

On 14th July, 1985, Laing agreed to be interviewed by Anthony Clare on the BBC Radio 4 programme, In the Psychiatrist's Chair. Clare later recalled that when Laing met at the studio, "drugs, drink and a significant degree of Celtic melancholia had taken their toll". He added that many parents of "sufferers from schizophrenia cannot forgive Laing either for adding the guilt of having 'caused' the illness in the first place to their strains and stresses of having to be the main providers of support, the communities that truly cares for their sick offspring". (117)

Kay Carmichael also interviewed him that year for the Glasgow Herald: "Listening to him talk about his childhood is painful. He acts out in front of you the terrible dilemma of the human being whose heart has never been satisfied, who has never felt totally loved, totally accepted, who knows that the time for experiencing that has passed, who understands why it hasn't happened, who would like to forgive his parents because in his head he knows that they were acting out their own dramas, but at the same time is still screaming for the unconditional love they couldn't give him. His anger is still raw." (118)

The following year Laing decided to become a member of the Church of Scotland. In an article published in The Times Literary Supplement Laing explained his decision: "He (God) is neither male nor female, nor both, nor neither, nor neither neither. Similarly he is not named any name we care to give him, including 'Him'. At the same time, I believe in God, because I can't possibly see how a Being beyond all my imagination, concepts or visions of such Being-as-Such, cannot, must not be. For want of a better word, I believe in God." (119)

On 10th November, 1986, Laing received news of his mother's death. According to his friend, Bob Mullan: "He (Laing) wept, and declared that he wished he had hurt his mother more... Laing reneged on his promise to his mother that he would not attend her funeral, and flew to Glasgow and did precisely that. In the presence of Amelia's coffin Laing wept uncontrollaby." (120)

The following year the General Medical Council wrote to him they were investigating an allegation against him of "serious professional misconduct" following a complaint from one of his previous patients who claimed that a drunken Laing had thrown him out of a session. The GMC questioned Laing's fitness to practise as a psychiatrist, especially given his "misuse of alcohol". On 26th February, 1987, the GMC suggested that if he withdrew from the medical register, no further action would be taken. Laing agreed and he retired from the profession. (121)

On 6th January, 1988, Marguerite gave birth to Laing's tenth child, Charles. Three months later they moved to Austria. He had given up alcohol and spent most of his time playing with the baby. On 23rd August, 1989, while on holiday in St Tropez, he felt unwell. "This may be the day" he remarked to Marguerite. Despite this worry, that afternoon he played a vigorous game of tennis. During the game he suffered a heart-attack and died in the arms of his 19 year-old daughter, Natatsha. (122) .

Primary Sources

(1) Antonin Artaud, Van Gogh, the Suicide Provoked by Society, Horizon: A Review of Literature and Art (January, 1948)

Van Gogh's painting does not attack a certain conformity of convention so much as the conformity of institutions. Institutions disintegrate on the social level; and medical science, by asserting Van Gogh's madness, shows itself to be an unserviceable, irresponsible corpse. Psychiatry, challenged by Van Gogh's lucidity at work, is no more than an outpost of, gorillas, themselves obsessed and persecuted,. who have only a ridiculous terminology to alleviate the most appaling states of anguish and human suffocation: a fitting product of their disreputable brains.

Van Gogh's body, free from all sin, was also free from that madness which is only induced by sin. And I do not believe in Catholic sin, but I do believe in erotic crime. It is precisely the world's geniuses and authentic lunatics in the asylums who are innocent of this crime; and if they are not, it is because they are not (authentically) lunatics.

And what is an authentic lunatic? He is a man who has preferred to become what is socially understood as mad rather than forfeit a certain superior idea of human honour. In its asylums, society has managed to strangle all those it has wished to rid itself of or to defend itself from, because they refused to make themselves accomplices to various flagrant dishonesties. For a lunatic is also a man whom society has not wished to listen to, and whom it is determined to prevent from uttering unbearable truths. But in such a case, internment is not its only weapon, and the social collectivity has other means to subdue those minds it wishes to suppress. Apart from the trifling influences of the small-town witch doctors, there are the vast onsets of world-wide spells, participated in from time to time by the totality of alarmed conscience. By these means the universal conscience, during a war, a revolution or a potential social upheaval, is called in question, interrogates itself and passes its judgements. It can also be provoked and brought out of itself in the case of certain sensational individual examples. There have been the unanimous outbreaks with regard to Baudelaire, Edgar Poe, Gerard de Nerval, Nietzsche, Kierkegaard, Holderlin and Coleridge - and

there has also been one about Van Gogh.The few lucid, well-disposed people who have had to struggle on this earth, see themselves at certain hours of the day and night from the depths of various phases of authentic recollected nightmare, overwhelmed by the powerful suction of the formidable, tentacle-like oppression of a kind of civic bewitchment which soon openly expresses itself in the general conventions. In comparison with this universal filth, based on sex on one hand and on mass or some such other psychic ritual on the other, there is no madness in walking around at night in a hat fitted with twelve candles in order to paint a landscape on the spot. As for the burnt hand, that was pure and simple heroism. The cut-off ear was

straightforward logic. I repeat: a world which every day and night increasingly eats the uneatable in order to adapt its bad faith to its own ends is forced, as far as this bad faith is concerned, to keep it under lock and key.

(2) R. D. Laing, Wisdom, Madness and Folly (1986)

Insulin was administered at six o'clock in the morning and within four hours the patients began to go into coma. The course of insulin started off with ten units, increased daily by ten units until the patients went into deep comas and sometimes epileptic fits. The policy was to put it in at a level at which epileptic fits were liable to occur, but to avoid them if possible. Backs could break. Light is extremely epileptogenic under a lot of insulin. The ward was entirely blacked out. When people started to go into coma we, the staff, moved around in total darkness, penetrated only by the rays of the torches on hinges we had strapped to our foreheads. It was essential to get each patient out of his or her coma before too long, because if we did not, the coma became `irreversible'. Around ten o'clock, we poured quantities of 50 per cent glucose into the patients through stomach tubes. We hoped we had got the tube into the stomach rather than the lungs.

Difficult to tell sometimes with someone in a coma. We often had to put up pressurized glucose drips in the darkness for patients already completely collapsed whose veins had disappeared. There were those who had no veins left because - of thrombosis everywhere caused by veins bursting under pressure, and needles would miss the vein, glucose solution pouring into tissues. One might have to take a scalpel to 'cut down' and stick a needle into something one just hoped was not an artery or a nerve. We only had our headlights.

(3) R. D. Laing, letter to Marcelle Vincent (1951)

In his life (a patient named John) he has had virtually nothing of the things he had set his heart on; he is well aware that he is regarded as mad but he says that why should he not be: now he is anyone he wants to be: has anything he wants: does everything he likes: why should he return to a world where he is unable to satisfy every one of his fundamental desires? Why indeed I find it very difficult to give him an answer. Insanity, suicide or sanity. In the specific sense in which Sartre uses the word, we are "free" to choose insanity or suicide. And more and more people are exercising their freedom in this direction.

(4) R. D. Laing, The Lancet (31st December, 1955)

In the last twelve months many changes occurred in these patients. They were no longer social isolates. Their conduct became more social, and they undertook tasks which were of more value in their small community. Their appearance and interest in themselves improved as they took a greater interest in those around them. These changes were satisfying to the staff. The patients lost many of the features of chronic psychoses; they were less violent to each other and to the staff, they were less dishevelled, and their language ceased to be obscene. The nurses came to know the patients well, and spoke warmly of them.

We started this work with the idea of giving patients and nurses the opportunity to develop interpersonal relationships of reasonably enduring nature. A physical environment was supplied which was clean and pleasant: and materials for knitting, sewing and drawing, a gramophone, foodstuffs, and facilities for cooking were made available, and the patients and nurses were left to make what use of them they wished. But our observations on the results seem to us to support the view that what matters most in the patient's environment is the people in it. The nurses found it useless merely to try to get the patients to do something; but, once the patients liked the nurses, attempts to help them became the basis for apparently autonomous activity in which the patients used the material in the environment. Disturbance and rupture of the relation, perhaps because of the absence of a particular nurse, or to some failure in her understanding interrupted this activity.