On this day on 20th June

On this day in 1832 William Cobbett described the plight of handloom weavers in the Political Register. "It is truly lamentable to behold so many thousands of men who formerly earned 20 to 30 shillings per week, now compelled to live upon 5s, 4s, or even less. It is the more sorrowful to behold these men in their state, as they still retain the frank and bold character formed in the days of their independence."

On this day in 1837 William IV died. William, the third son of George III, was born at Buckingham Palace in 1765. He entered the navy in 1779, and saw service in America and the West Indies. In 1789 he was granted the title, the Duke of Clarence and given an allowance of £12,000 a year. William remained in the navy and by 1811 had reached the rank of admiral.

Like his brother George IV, William rebelled against his father's strict discipline. He lived with his mistress, the actress Dorothy Jordon, who bore him ten children. William also against his father's political views. Whereas George III preferred the Tories, William was a Whig, and at once time even considered becoming a Member of Parliament. In the House of Lords the Duke of Clarence supported Catholic Emancipation and showed signs he favoured parliamentary reform.

After the death of George IV's daughter, Princess Charlotte, in 1818, there was a royal scramble to marry an heir to the throne. Soon after Charlotte's death, William married Adelaide, eldest daughter of the Duke of Saxe-Coburg. The couple had two daughters but they both died in infancy.

When his brother, George IV, died in 1830, the Duke of Clarence became king. Like his father and brother, William IV was prone to strange behaviour. On the day he became king he raced through London in an open carriage, frequently removing his hat and bowing to his new subjects. Every so often he stopped and offered people a lift in his royal carriage. His habit of spitting in public also helped to obtain for him a reputation as an eccentric.

At first William IV was very popular. The people were pleased when he announced that he would attempt to keep royal spending to a minimum. People became convinced that he meant what he said when it was discovered that William's coronation only cost a tenth of the expense incurred by George IV's ceremony in 1821. In November 1830 Lord Grey and the Whigs came to power. The king told Grey that he would not interfere with Whig plans to introduce parliamentary reform.

In April 1831 Grey asked the king to dissolve Parliament so that the Whigs could secure a larger majority in the House of Commons. Grey explained this would help his government to carry their proposals for an increase in the number of people who could vote in elections. William agreed to Grey's request and after making his speech in the House of Lords, decided to walk back through cheering crowds to Buckingham Palace.

After Lord Grey's election victory, he tried again to introduce parliamentary reform but once again the Lords refused to pass the bill. On 7th May 1832, Grey and Henry Brougham met the king and asked him to create a large number of Wigg peers in order to get the Reform Bill passed in the House of Lords. William was now having doubts about the wisdom of parliamentary reform and refused.

Lord Grey's government resigned and William IV now asked the leader of the Tories, the Duke of Wellington, to form a new government. Wellington tried to do this but some Tories, including Sir Robert Peel, were unwilling to join a cabinet that was in opposition to the views of the vast majority of the people in Britain. Peel argued that if the king and Wellington went ahead with their plan there was a strong danger of a civil war in Britain.

When the Duke of Wellington failed to recruit another significant figures into his cabinet, William was forced to ask Grey to return to office. In his attempts to frustrate the will of the electorate, William IV lost the popularity he had enjoyed during the first part of his reign. Once again Lord Grey asked the king to create a large number of new Whig peers. William agreed that he would do this and when the Lords heard the news, they agreed to pass the Reform Act.

William IV resented the fact that Lord Grey had forced the Reform Act on him. However, Grey was so popular with the general public that he was unable to take action against him. After Grey resigned in 1834 and was replaced by Lord Melbourne, the king was in a stronger position.

In November 1834 William IV dismissed the Whig government and appointed the Tory, Sir Robert Peel as his new prime minister. By this time the king had developed an intense dislike for the Whig reformers such as Lord John Russell and Henry Brougham.

As there were more Whigs than Tories in the House of Commons, Sir Robert Peel found government very difficult. Peel was only able to pass legislation that was supported by the Whigs and on 8th April 1835 he resigned from office. The Tories were replaced by a Whig government and once again William had to preside over a series of reforms that he profoundly disagreed with.

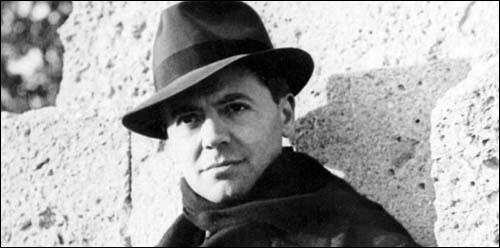

On this day in 1899 Jean Moulin, the son of a professor of history, was born in Belziers, France. He was conscripted into the French Army in 1918 but the First World War came to an end before he had the opportunity to see action.

After the war Moulin joined the civil service and rose rapidly to become the country's youngest prefect. Influenced by his friend, Pierre Cot, a radical pacifist, Moulin developed left-wing views. During the Spanish Civil War Moulin helped to smuggle a French aircraft to the Republican Army fighting against the Royalists.

Moulin refused to cooperate with the German Army when they occupied France in June 1940. He was arrested and tortured by the Gestapo and while in his cell he attempted to commit suicide by cutting his throat with a piece of broken glass. After recovering he was released from prison.

In November 1940, the Vichy government ordered all prefects to dismiss left-wing mayors of towns and villages that had been elected to office. When Moulin refused to do this he was himself removed from office.

Over the next few months Moulin began to make contact with other French people who wanted to overthrow the Vichy government and to drive the German Army out of France. This included Henry Frenay, who had established Combat, the most important of all the early French Resistance groups. He also had discussions with Pierre Villon who was attempting to organize the communist resistance group in France. Later, Moulin was accused of being a communist but there is no evidence that he ever joined the party.

Moulin visited London in September, 1941 where he met Charles De Gaulle, Andre Dewavrin and other French leaders in exile. In October 1941, Moulin produced a report entitled The Activities, Plans and Requirements of the Groups formed in France. De Gaulle was impressed with Moulin knowledge of the situation and decided he should become the leader of the resistance in France.

Moulin was parachuted back into France on 1st January, 1942. Moulin brought with him a large sum of money to help set up the underground press. This included working with figures such as Georges Bidault and Albert Camus who had both been involved in establishing the Combat newspaper.

Moulin's main task was to try and unite all the different resistance groups working in France. Over the following weeks he arranged meetings with people such as Henry Frenay (Combat), Emmanuel d'Astier (Liberation), Jean-Pierre Lévy (Francs-Tireur), Pierre Villon (Front National), Pierre Brossolette (Comité d'Action Socialiste) and Charles Delestraint (Armée Secrete). After much discussion Moulin persuaded the eight major resistance groups to form the Conseil National de la Resistance (CNR) and the first joint meeting under Moulin's chairmanship took place in Paris on 27th May 1943.

On 7th June 1943, René Hardy, an important member of the resistance in France, was arrested and tortured by Klaus Barbie and the Gestapo. They eventually obtained enough information to arrest Jean Moulin at Caluire on 21st June. Jean Moulin died while being tortured on 8th July 1943.

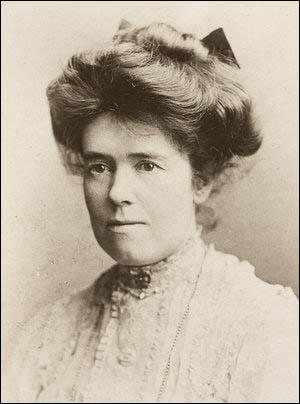

On this day in 1905 writer Lillian Hellman was born in New Orleans on 20th June, 1905. After graduating from New York University she worked as a publisher's reader.

Hellman's first play, The Children's Hour (1934), which tells of the havoc caused by a schoolgirl's invention of a lesbian relationship, was an immediate success. Hellman held left-wing political views and was active in the campaign against the growth of fascism in Europe. She joined other literary figures such as Dashiell Hammett, Clifford Odets, Arthur Miller, John Dos Passos and Ernest Hemingway in supporting the Republicans during the Spanish Civil War.

In 1939 Hellman had her second major success with her play about a Southern family, the Hubbards. The Little Foxes was followed by two anti-Nazi plays, Watch on the Rhine (1941) and The Searching Wind (1944). Her next play, Another Part of the Forest (1946) once again dealt with the Hubbard family.

As a result of her well-known political views, in 1951 Hellman and her partner, Dashiell Hammett, were called to appear before the House of Un-American Activities Committee. Hellman agreed to talk about her own involvement with radical groups, but was unwilling to give names of her comrades and as a result was blacklisted. Hammett, as well as being blacklisted, was sent to prison for six months.

Hellman wrote two more plays, Autumn Gardens (1951) and Toys in the Attic (1960), and three volumes of autobiography, An Unfinished Woman (1969), Pentimento (1973) and Scoundrel Time (1976).

Lillian Hellman died at Martha's Vineyard, on 30th June, 1984.

On this day in 1912 Dora Marsden argues in The Freewoman that sexual equality will never be achieved under a capitalist system. On 28th December 1911, Marsden began a five-part series on morality. Dora argued that in the past women had been encouraged to restrain their senses and passion for life while "dutifully keeping alive and reproducing the species". She criticised the suffrage movement for encouraging the image of "female purity" and the "chaste ideal". Dora suggested that this had to be broken if women were to be free to lead an independent life. She made it clear that she was not demanding sexual promiscuity for "to anyone who has ever got any meaning out of sexual passion the aggravated emphasis which is bestowed upon physical sexual intercourse is more absurd than wicked."

Dora Marsden went on to attack traditional marriage: "Monogamy was always based upon the intellectual apathy and insensitiveness of married women, who fulfilled their own ideal at the expense of the spinster and the prostitute." According to Marsden monogamy's four cornerstones were "men's hypocrisy, the spinster's dumb resignation, the prostitute's unsightly degradation and the married woman's monopoly." Marsden then added "indissoluble monogamy is blunderingly stupid, and reacts immorally, producing deceit, sensuality, vice, promiscuity and an unfair monopoly." Friends assumed that Marsden was writing about her relationships with Grace Jardine and Mary Gawthorpe.

Dora argued that it would be better if women had a series of monogamous relationships. Les Garner, the author of A Brave and Beautiful Spirit (1990) has argued: "How far her views were based on her own experience it is difficult to tell. Yet the notion of a passionate but not necessarily sexual relationship would perhaps adequately describe her friendship with Mary Gawthorpe, if not others too. Certainly, her argument would appeal to single women like herself who had sexual desires and feelings but were not allowed to express them - unless, of course, in marriage. Even then, sex, for women at least, was supposed to be reserved for procreation."

Charlotte Payne-Townshend Shaw, the wife of George Bernard Shaw, wrote to Dora Marsden "though there has been much I have not agreed with in the paper", The Freewoman was nevertheless a "valuable medium of self-expression for a clever set of young men and women". However, Olive Schreiner disagreed and argued that the debates about sexuality were inappropriate and revolting in a publication of "the women's movement". Frank Watts wrote a letter to the journal that if women really wanted to discuss sex "then it must be admitted by sane observers that man in the past was exercising a sure instinct in keeping his spouse and girl children within the sheltered walls of ignorance."

Harry J. Birnstingl praised Marsden for raising the subject of homosexuality. He added: "It apparently has never occurred to them that numbers of these women find their ultimate destiny, as it were, among members of their own sex, working for the good of each other, forming romantic - nay passionate - attachments with each other? It is splendid that these women... should suddenly find their destiny in thus working together for the freedom of their own sex. It is one of the most wonderful things of the twentieth century."

By the summer of 1912 Dora Marsden had become disillusioned with the parliamentary system and no longer considered it important to demand women's suffrage: "The politics of the community are a mere superstructure, built upon the economic base... even though Mr. George Lansbury were Prime Minister and every seat in the House occupied by Socialist deputies, the capitalist system being what it is they would be powerless to effect anything more than the slow paced reform of which the sole aim is to make men and masters settle down in a comfortable but unholy alliance... the capitalists own the states. A handful of private capitalists could make England, or any other country, bankrupt within a week."

This article brought a rebuke from H. G. Wells: That you do not know what you want in economic and social organization, that the wild cry for freedom which makes me so sympathetic with your paper, and which echoes through every column of it, is unsupported by the ghost of a shadow of an idea how to secure freedom. What is the good of writing that economic arrangements will have to be adjusted to the Soul of Man if you are not prepared with anything remotely resembling a suggestion of how the adjustment is to be affected?"

Mary Gawthorpe also criticised Dora Marsden for her what she called her "philosophical anarchism". She told her that she "was not really an anarchist at all" but one who believed in rank, with herself at the top. Mary added: "Intellectually you have signed on as a member of the coming aristocracy. Free individuals you would have us be, but you would have us in our ranks... I watch you from week to week governing your paper. You have your subordinates. You say to one go and she goes, to another come, and she comes."

In September 1912, The Freewoman was banned by W. H. Smith because "the nature of certain articles which have been appearing lately are such as to render the paper unsuitable to be exposed on the bookstalls for general sale." Dora Marsden argued that this was not the only reason the journal was banned: "The animosity we rouse is not roused on the subject of sex discussion. It is aroused on the question of capitalism. The opposition in the capitalist press only broke out when we began to make it clear that the way out of the sex problem was through the door of the economic problem."

On this day in 1913 WSPU members Edwy Godwin Clayton (21 months), Annie Kenney (18 months) and Rachel Barrett (6 months) are found guilty of conspiring to damage property.

On 30th April 1913 the police raided the WSPU's office at Lincoln's Inn House. As a result of the documents found several people were arrested. When he was arrested Clayton said: "I think this is rather a high-handed action. I am an extreme sympathizer with the Suffragette causes. What evidence have you against me?" He confirmed he had written the letter but refused to comment on the contents. The letter read: "Dear Miss Kenney, I am sorry to say it will be several days yet before I can be ready with which you want. I have devoted all this evening and all of yesterday evening to the business without success. Evidently it is a difficult matter, but not impossible. I nearly succeeded once last night and then spoilt what I had done in trying to improve upon it. By next week I shall be able to manage the exact proportions, and I will let you have the results as soon as I can. Please burn this."

During the trial Matthias McDonnell Bodkin read extracts from a document headed "Votes for Women" and underneath "YHB". Bodkin claimed that YHB stood for Young Hot Bloods. The label was derived from a taunt thrown at Emmeline Pankhurst in one of the newspapers, which ran: "Mrs Pankhurst will, of course, be followed blindly by a number of the younger and more hot-blooded members of the union". As a result of them being single women one newspaper described the Young Hot Bloods as "a spinsters' secret sect".

Bodkin claimed that the police seized a great number of documents, that showed according to Bodkin that Clayton "put his knowledge and his brain at the Union's disposal for the purpose of carrying out crimes and of producing the reign of terror in London." Receipts for money he had been paid by the union were produced in court.

The most incriminating evidence was a letter sent by Edwy Godwin Clayton to Jessie Kenney in April 1913 that was found inside a book on the 1831 Bristol Reform Riots. Bodkin said: "We did not know until these documents were seized at their offices that they had an analytical chemist in their service – a man who, as we know, written a secret letter which the vain folly of Miss Kenney causes her to leave in her bedroom. the letter he tells her he had been experimenting, and was on the brink of success. Clayton ended his letter: "Burn this letter."

Bodkin provided other documents written by Clayton. One document in Clayton's writing was headed "Various Suggestions" and read "Scheme of simultaneously smashing a considerable number of street fire-alarms. This will cause tremendous confusion and excitement and should be as especially a good idea. It should be at once easier and less risky to execute than some other operations". Particulars as to timber yards and cotton mills also followed, as well as a plan for burning down the National Health Insurance Office.

In his summing up Justice Walter Phillimore, remarked that it was one of the saddest trials in his experience of nearly sixteen years as a Judge. "How in morals and how in good practical sense could such things, if they be true be justified? It was said that great causes had never been won without breaking the law. That might be true of some cases; it was very untrue of others. If every recorded act of anarchy, then, as history proceeded on its long course, the human race would reach a position of absolute savagery, and the only chance of salvation would be the obliteration of memory."

During the trial, Rachel Barrett said: "When we hear of a bomb being thrown we say 'Thank God for that'. If we have any qualms of conscience, it is not because of things that happen, but because of things that have been left undone." (21) Barrett was described by one of the prosecuting barristers at the trial as "a pretty but misguided young woman". (22)

After an absence of an hour the jury found all the prisoners guilty, with strong recommendations for leniency of sentence in the case of the three younger women, Rachel Barrett, Geraldine Lennox and Agnes Lake. The Judge said: "I agree with you, gentlemen of the jury, in the discrimination which you have made between the younger and elder men and women… which I propose to show in their sentences: As I have said, I assume you have been animated through out by the best motives. It is not merely that some of you have committed organized outrages, but I am more concerned with the incitement that has been given to young and irresponsible women, whose actions are not always balanced by their reason to do things which you are sure to regret." (23)

Barrett was sentenced to six months in prison but Annie Kenney was sentenced to eighteen months and Edwy Godwin Clayton got twenty-one months. Barrett immediately began a hunger strike in Holloway Prison. After five days she was released under the Cat and Mouse Act. Barrett was re-arrested and this time went on a hunger and thirst strike. When she was released she escaped to Edinburgh. where she was looked after by Dr Flora Murray. (24)

On this day in 1933 Rose Pastor Stokes died in Frankfurt on 20th June, 1933. According to Judith Rosenbaum: "In 1930, Stokes was diagnosed with a malignant breast tumor, which she attributed to having received a blow on the breast from a policeman’s club during a demonstration - claiming martyrdom for the proletarian cause. Her health rapidly declined; even so, she maintained her radical, fighting spirit. Although her illness prevented her from remaining active in the Communist Party during the last years of her life, she continued to assert her allegiance to it."

Rose Wieslander, the daughter of Jacob and Anna Wieslander, was born in Russia on 18th July 1879. When the marriage broke down, Anna brought Rose to the East End of London. Soon afterwards, Anna married Israel Pastor.

Rose Pastor attended Bell Lane Free School but at the age of eight she found work in a Whitechapel factory. In 1891 the family emigrated to Cleveland, Ohio. According to her biographer, Judith Rosenbaum: "Rose found work in a 'buck-eye', the cigar-sweatshop in which many Jews labored. She worked as an unskilled 'stogey-roller' for twelve years. After Israel Pastor abandoned the family, she became the sole supporter of six. For those who later popularized her character in the media, this period of her life often faded to an idealized working-class experience, but for Rose herself, it stood out as formative for her identity."

Rose Pastor sent regular letters to the Jewish Daily News. The editor was impressed with her contributions and in 1902 she was offered a regular column in the newspaper with a salary of $15 per week. Rose now moved to New York City and took an apartment in Lower East Side.

Rose Pastor took a keen interest in politics and began a series of articles on university settlements. The movement, based on the achievements of Toynbee Hall in the East End of London, had been established by Jane Addams and Ellen Starr at Hull House in Chicago in 1889. The idea behind the movement was that people from privileged backgrounds should live amongst the poor.

In 1903 she interviewed Graham Stokes, the New York City millionaire who at that time a supporter of the University Settlement in the city. James Boylan, the author of Revolutionary Lives: Anna Strunsky and William English Walling (1998), has pointed out: "James Graham Phelps Stokes... brother of the architect, Newton... was a member of one of the city's old and wealthy mercantile families; he had to look after family businesses, but his heart was with New York's social and reform enterprises, which placed him on more boards and committees than he could efficiently serve. The Stokeses were particularly important to the University Settlement; in addition to Newton's role, his sisters were part-time volunteers, and Graham himself was a member of the governing council."

Rose Pastor was very impressed with what Stokes had to say and became a volunteer worker at the settlement. The couple were married in July 1905 and moved to a house in Greenwich, Connecticut. Later that year the couple joined the Socialist Party of America. Other members included Eugene Debs, Victor Berger, Ella Reeve Bloor, Emil Seidel, Daniel De Leon, Philip Randolph, Chandler Owen, William Z. Foster, Abraham Cahan, Sidney Hillman, Morris Hillquit, Walter Reuther, Bill Haywood, Margaret Sanger, Florence Kelley, Mary White Ovington, Helen Keller, Inez Milholland, Floyd Dell, William Du Bois, Hubert Harrison, Upton Sinclair, Agnes Smedley, Victor Berger, Robert Hunter, George Herron, Kate Richards O'Hare, Helen Keller, Claude McKay, Sinclair Lewis, Daniel Hoan, Frank Zeidler, Max Eastman, Bayard Rustin, James Larkin, William Walling and Jack London.

In September 1905, Rose Pastor Stokes and Graham Stokes joined with Upton Sinclair, Jack London, Clarence Darrow and Florence Kelley to form the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. The main objective of the organization was to encourage study and discussion of socialism in colleges. Rose continued work as a journalist and was a regular contributor to the The Masses and The Call.

Although Rose Pastor Stokes was now extremely wealthy she remained a committed socialist. As Eugene Debs pointed out: "She had her millions of dollars at command. Did her wealth restrain her an instant? On the contrary her supreme devotion to the cause outweighed all considerations of a financial or social nature. She went out boldly to plead the cause of the working class."

On the outbreak of the First World War most socialists in the United States were opposed to the conflict. They argued that the war had been caused by the imperialist competitive system and argued that the America should remain neutral. This was also the view expressed in the three main socialist journals, Appeal to Reason, The Masses and The Call.

Rose Pastor Stokes was also involved in the struggle to keep the United States out of the war. Graham Stokes disagreed with her on this issue and along with his friends, William English Walling, Jack London, Charles Edward Russell, John Spargo and Upton Sinclair, thought that President Woodrow Wilson should send troops to fight the German Army in Europe. Stokes began to attack those in the the American Socialist Party who opposed the war as really being secret supporters of Germany.

Emma Goldman was furious with Graham Stokes and other pro-war socialists and wrote in Mother Earth: "The black scourge of war in its devastating effect upon the human mind has never been better illustrated than in the ravings of the American Socialists, Messrs. Russell, Stokes, Sinclair, Walling, et al.... As to English Walling, he was the reddest of the red. Though muddled mentally he was always at white heat emotionally as syndicalist, revolutionist, dissenter, etc... One might overlook the renegacy of a Charles Edward Russell. Nothing else need ever be expected from a journalist. But for men like Stokes and Walling to thus become the lackeys of Wall Street and Washington, is really too cheap and disgusting."

Rose Pastor Stokes continued her campaign against the war. On 22nd March, 1918, she was arrested and charged under the Espionage Act. She was accused of making anti-war speeches but the authorities were especially upset by a letter she sent to Kansas City Star where she argued: "No government which is for the profiteers can also be for the people, and I am for the people, while the government is for the profiteers.” She was found guilty and sentenced to ten years in prison. Stokes’s conviction was appealed twice before the decision was reversed in March 1920, on the grounds that the charge to the jury was prejudicial against the defendant.

Rose Pastor Stokes experiences moved her to the revolutionary left. The right-wing leadership of the Socialist Party of America opposed the Russian Revolution. On 24th May 1919 the leadership expelled 20,000 members who supported the Soviet government. The process continued and by the beginning of July two-thirds of the party had been suspended or expelled.

In September 1919, Rose Pastor Stokes, Jay Lovestone, Earl Browder, John Reed, James Cannon, Bertram Wolfe, William Bross Lloyd, Benjamin Gitlow, Charles Ruthenberg, Mikhail Borodin, William Dunne, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Louis Fraina, Ella Reeve Bloor, Juliet Poyntz, Nathan Silvermaster, Jacob Golos, Claude McKay, Max Shachtman, Martin Abern, Michael Gold and Robert Minor, decided to form the Communist Party of the United States. Within a few weeks it had 60,000 members whereas the Socialist Party of America had only 40,000.

Graham Stokes did not share his wife's communist beliefs. Rose suggested they had become "friendly enemies". In 1925 her husband brought a petition for divorce on grounds of misconduct.

In 1925 Rose became involved with Victor Jerome. At the time he was twenty-nine and she was forty-seven. Stokes wrote to Jeanette Pearl about the new man in her life: "I'm interfering with his studies and I'm afraid he's interfering with my peace of mind.... I'm mighty near being at that extent that I shall lose all sane judgment. Don't fall in love, Jean. It's an enslaver of life." The couple married in February, 1927.

In 1929 Rose Pastor Stokes was seriously injured when clubbed by police at a demonstration demanding the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Haiti. According to a report in the Daily Chronicle Rose "was struck while attempting to protect a young boy from a policeman".

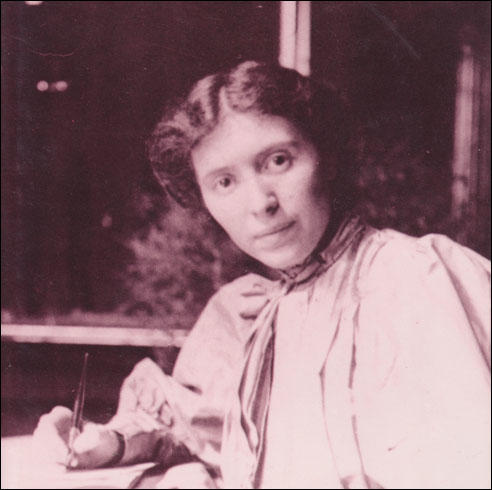

On this day in 1933 Marxist philosopher Clara Zetkin died.

Clara Eissner, the daughter of Gottfried Eissner, a local schoolmaster, was born in Wiederau, Saxony, on 5th July, 1857. While studying at Leipzig Teacher's College for Women she became a socialist and feminist.

In 1875 August Bebel and Wilhelm Liebknecht, the founders of the Social Democratic Workers' Party of Germany (SDAP), merged it with the General German Workers' Association (ADAV), an organisation led by Ferdinand Lassalle, to form the Social Democratic Party (SDP). Clara was one of those who joined the new party. In the 1877 General Election in Germany the SDP won 12 seats. This worried Otto von Bismarck, and in 1878 he introduced an anti-socialist law which banned SDP meetings and publications.

Clara, like other members of the SDP left for Zurich in 1882 and then moved on to live in exile in Paris. During this period Clara read Woman and Socialism. In the book August Bebel argued that it was the goal of socialists "not only to achieve equality of men and women under the present social order, which constitutes the sole aim of the bourgeois women's movement, but to go far beyond this and to remove all barriers that make one human being dependent upon another, which includes the dependence of one sex upon another." She later wrote that out of this book "streams of life poured forth; thus it was that his great firmness in principles and tactics did not appear as dry, rigid dogmatism, but seemed, on the contrary, to breathe forth the natural freshness of life itself."

A strong supporter of international socialism, Clara married Ossip Zetkin, a Russian revolutionary who was living in exile. Ossip was a carpenter, a Marxist, and according to her mother was a "good-for-nothing". In 1883, her son Maxim, was born, followed by Kostya in 1885. In Paris she met other leading socialists from France, Germany and Russia. She was active politically, worked as a journalist and took up a role of "teacher and Educator".

Clara and Ossip Zetkin became members of the international socialist group, Cercle Internationale, which met weekly to discuss questions of Marxist theory and to plan action. "Here the Zetkins came into contact not only with Russian, German and French socialists, but with socialists from Spain, Italy, Austria and Britain as well. It was in this period that Clara Zetkin gained her vast knowledge of the international labour movement, as well as her proficiency in a number of languages." Ossip Zetkin died of tuberculosis in January, 1889.

Ossip Zetkin died of tuberculosis in January, 1889. Clara continued with her political campaigns. She refused to join the Berlin Association of Proletarian Women and Girls because it accepted only women as members. Clara disapproved of the "segregation of women and men" and regretted the "feminist tendencies... of many outstanding supporters of the Berlin movement". Zetkin was initially critical of the demand for female suffrage because "without economic freedom it changes absolutely nothing". She saw it as being a middle-class movement.

Zetkin took a particular interest in supporting women workers in their demand for higher wages: "What made women's labour particularly attractive to the capitalists was not only its lower price but also the greater submissiveness of women. The capitalists speculate on the two following factors: the female worker must be paid as poorly as possible and the competition of female labour must be employed to lower the wages of male workers as much as possible. In the same manner the capitalists use child labour to depress women's wages and the work of machines to depress all human labour."

After the anti-socialist law ceased to operate in 1890, Zetkin returned to Germany. Membership grew rapidly but August Bebel and Wilhelm Liebknecht had problems with divisions in the party. Eduard Bernstein, a member of the SDP, who had been living in London, became convinced that the best way to obtain socialism in an industrialized country was through trade union activity and parliamentary politics. He published a series of articles where he argued that the predictions made by Karl Marx about the development of capitalism had not come true. He pointed out that the real wages of workers had risen and the polarization of classes between an oppressed proletariat and capitalist, had not materialized. Nor had capital become concentrated in fewer hands.

Eduard Bernstein's revisionist views appeared in his extremely influential book Evolutionary Socialism (1899). His analysis of modern capitalism undermined the claims that Marxism was a science and upset leading revolutionaries such as Lenin and Leon Trotsky. In 1900, Rosa Luxemburg published an attack on Bernstein in her pamphlet, Reform or Revolution.

Luxemburg argued: "He (Bernstein), who wants to pass as a socialist, and at the same time declare war on Marxian doctrine, the most stupendous product of the human mind in the century, must begin with involuntary esteem for Marx. He must begin by acknowledging himself to be his disciple, by seeking in Marx’s own teachings the points of support for an attack on the latter, while he represents this attack as a further development of Marxian doctrine. On this account, we must, unconcerned by its outer forms, pick out the sheathed kernel of Bernstein’s theory. This is a matter of urgent necessity for the broad layers of the industrial proletariat in our Party."

In 1891 Clara Zetkin became editor of the SPD's journal, Die Gleichheit (Equality). An impressive journalist, Zetkin took the circulation from 11,000 in 1903 to 67,000 three years later. Zetkin now changed her views on women's suffrage and helped to organize the first International Conference of Socialist Women in Struttgart. The conference was attended by 58 female delegates from 15 countries in Europe. During the conference "the socialist parties of all countries committed themselves to energetically championing female suffrage without any restrictions." This was in contrast to middle class women who were willing to accept "restricted female suffrage" or "ladies' suffrage".

Karl Liebknecht was a leading figure in the anti-militarist section of the SDP. In 1907 he published Militarism and Anti-Militarism. In the book he argued: "Militarism is not specific to capitalism. It is moreover normal and necessary in every class-divided social order, of which the capitalist system is the last. Capitalism, of course, like every other class-divided social order, develops its own special variety of militarism; for militarism is by its very essence a means to an end, or to several ends, which differ according to the kind of social order in question and which can be attained according to this difference in different ways. This comes out not only in military organization, but also in the other features of militarism which manifest themselves when it carries out its tasks. The capitalist stage of development is best met with an army based on universal military service, an army which, though it is based on the people, is not a people’s army but an army hostile to the people, or at least one which is being built up in that direction."

Liebknecht then went on to argue why the socialist movement should concentrate on persuading young people to adopt the philosophy of anti-militarism: "Here is a great field full of the best hopes of the working-class, almost incalculable in its potential, whose cultivation must not at any cost wait upon the conversion of the backward sections of the adult proletariat. It is of course easier to influence the children of politically educated parents, but this does not mean that it is not possible, indeed a duty, to set to work also on the more difficult section of the proletarian youth. The need for agitation among young people is therefore beyond doubt. And since this agitation must operate with fundamentally different methods – in accordance with its object, that is, with the different conditions of life, the different level of understanding, the different interests and the different character of young people – it follows that it must be of a special character, that it must take a special place alongside the general work of agitation, and that it would be sensible to put it, at least to a certain degree, in the hands of special organizations."

At this time Germany became involved in an arms race with Britain. The Royal Navy built its first dreadnought in 1906. It was the most heavily-armed ship in history. She had ten 12-inch guns (305 mm), whereas the previous record was four 12-inch guns. The gun turrets were situated higher than user and so facilitated more accurate long-distance fire. In addition to her 12-inch guns, the ship also had twenty-four 3-inch guns (76 mm) and five torpedo tubes below water. In the waterline section of her hull, the ship was armoured by plates 28 cm thick. It was the first major warship driven solely by steam turbines. It was also faster than any other warship and could reach speeds of 21 knots. A total of 526 feet long (160.1 metres) it had a crew of over 800 men. It cost over £2 million, twice as much as the cost of a conventional battleship.

Germany built its first dreadnought in 1907 and plans were made for building more. Kaiser Wilhelm II gave an interview to the Daily Telegraph in October 1908 where he outlined his policy of increasing the size of his navy: "Germany is a young and growing empire. She has a world-wide commerce which is rapidly expanding and to which the legitimate ambition of patriotic Germans refuses to assign any bounds. Germany must have a powerful fleet to protect that commerce and her manifold interests in even the most distant seas. She expects those interests to go on growing, and she must be able to champion them manfully in any quarter of the globe. Her horizons stretch far away. She must be prepared for any eventualities in the Far East. Who can foresee what may take place in the Pacific in the days to come, days not so distant as some believe, but days at any rate, for which all European powers with Far Eastern interests ought steadily to prepare?"

Karl Liebknecht led the campaign against the building of more dreadnoughts. Other members of the Social Democratic Party who supported Liebknecht became known as the Left Radicals. This included Leo Jogiches, Franz Mehring, Clara Zetkin, Paul Frölich, Hugo Eberlein, August Thalheimer, Bertha Thalheimer, Käte Duncker, Ernest Meyer, Wilhelm Pieck, Julian Marchlewski, Hermann Duncker and Anton Pannekoek. The leadership of the SDP agreed with the build-up of the armed forces in Germany and they saw a significant growth in their popularity. For example, in 1907 they won 43 seats in the Reichstag. Four years later they increased this to 110 seats.

On 4th August, 1914, Karl Liebknecht was the only member of the Reichstag who voted against Germany's participation in the First World War. He argued: "This war, which none of the peoples involved desired, was not started for the benefit of the German or of any other people. It is an Imperialist war, a war for capitalist domination of the world markets and for the political domination of the important countries in the interest of industrial and financial capitalism. Arising out of the armament race, it is a preventative war provoked by the German and Austrian war parties in the obscurity of semi-absolutism and of secret diplomacy."

Paul Frölich, a supporter of Liebknecht in the Social Democratic Party (SDP), argued: "On the day of the vote only one man was left: Karl Liebknecht. Perhaps that was a good thing. That only one man, one single person, let it be known on a rostrum being watched by the whole world that he was opposed to the general war madness and the omnipotence of the state - this was a luminous demonstration of what really mattered at the moment: the engagement of one's whole personality in the struggle. Liebknecht's name became a symbol, a battle-cry heard above the trenches, its echoes growing louder and louder above the world-wide clash of arms and arousing many thousands of fighters against the world slaughter."

John Peter Nettl claims that two left-wing members of the SDP, Rosa Luxemburg and Clara Zetkin, were horrified by these events. They had great hopes that the SDP, the largest socialist party in the world with over a million members, would oppose the war: "Both Rosa Luxemburg and Clara Zetkin suffered nervous prostration and were at one moment near to suicide. Together they tried on 2 and 3 August to plan an agitation against the war; they contacted 20 SPD members with known radical views, but they got the support of only Liebknecht and Mehring... Rosa sent 300 telegrams to local officials who were thought to be oppositional, asking their attitude to the vote in the Reichstag and inviting them to Berlin for an urgent conference. The results were pitiful."

Clara Zetkin later recalled: "The struggle was supposed to begin with a protest against the voting of war credits by the social-democratic Reichstag deputies, but it had to be conducted in such a way that it would be throttled by the cunning tricks of the military authorities and the censorship. Moreover, and above all, the significance of such a protest would doubtless be enhanced, if it was supported from the outset by a goodly number of well-known social-democratic militants.... Out of all those out-spoken critics of the social-democratic majority, only Karl Liebknecht joined with Rosa Luxemburg, Franz Mehring, and myself in defying the soul-destroying and demoralising idol into which party discipline had developed."

Clara Zetkin joined forces with Rosa Luxemburg, Ernest Meyer, Franz Mehring, Wilhelm Pieck, Julian Marchlewski, Hermann Duncker and Hugo Eberlein to campaign against the war but decided against forming a new party and agreed to continue working within the SPD. Clara Zetkin was initially reluctant to join the group. She argued: "We must ensure the broadest relationship with the masses. In the given situation the protest appears more as a personal beau geste than a political action... It is justified and nice to say that everything is lost, except one's honour. If I wanted to follow my feelings, then I would have telegraphed a yes with great pleasure. But now we must more than ever think and act coolly."

However, by September, 1914, Zetkin was playing a significant role in the anti-war movement. She co-signed with Luxemburg, Liebknecht and Mehring, letters that appeared in socialist newspapers in neutral countries condemning the war. Above all Zetkin used her position as editor-in-chief of the Die Gleichheit (Equality) and as Secretary of the Women's Secretariat of the Socialist International to propagate the positions of the anti-war movement.

Zetkin became very disillusioned with the growing nationalism of the Social Democratic Party. She wrote to her friend, Helen Ankersmit, about her concerns: "The most disastrous phenomenon of the current situation is the factor that imperialism is employing for its own ends all the powers of the proletariat, all of its institutions and weapons, which its fighting vanguard has created for its war of liberation. Social Democracy bears the main guilt and responsibility for this phenomenon before the International and history. The granting of the war credits was the harbinger for the equally comprehensive and revolting process of capitulation of German Social Democracy".

Karl Liebknecht continued to make speeches in public about the war: "The war is not being waged for the benefit of the German or any other peoples. It is an imperialist war, a war over the capitalist domination of the world market... The slogan 'against Tsarism' is being used - just as the French and British slogan 'against militarism' - to mobilise the noble sentiments, the revolutionary traditions and the hopes of the people for the national hatred of other peoples."

Clara Zetkin became involved in the Women's Peace Party that attempted to bring an end to the war. Other members included Mary Sheepshanks, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Chrystal Macmillan. Sylvia Pankhurst, Charlotte Despard, Helena Swanwick, Olive Schreiner, Helen Crawfurd, Alice Wheeldon, Jane Addams, Emily Greene Balch, Lida Gustava Heymann, Rosika Schwimmer; Aletta Jacobs and Emilia Fogelklou.

At a International Women's Peace Conference in March, 1915, at the Hague, Clara Zetkin argued: "Who profits from this war? Only a tiny minority in each nation: The manufacturers of rifles and cannons, of armor-plate and torpedo boats, the shipyard owners and the suppliers of the armed forces' needs. In the interests of their profits, they have fanned the hatred among the people, this contributing to the outbreak of the war. The workers have nothing to gain from this war, but they stand to lose everything that is dear to them."

In May 1915, Karl Liebknecht published a pamphlet, The Main Enemy Is At Home! He argued that: "The main enemy of the German people is in Germany: German imperialism, the German war party, German secret diplomacy. This enemy at home must be fought by the German people in a political struggle, cooperating with the proletariat of other countries whose struggle is against their own imperialists. We think as one with the German people – we have nothing in common with the German Tirpitzes and Falkenhayns, with the German government of political oppression and social enslavement. Nothing for them, everything for the German people. Everything for the international proletariat, for the sake of the German proletariat and downtrodden humanity."

In December, 1915, 19 other deputies joined Karl Liebknecht in voting against war credits. The following year a series of demonstrations took place. Some of these were "spontaneous outbursts by unorganised groups of people, usually women: anger would flare when a shop ran out of food, or put its prices up, or when rations were suddenly cut." These demonstrations often led to bitter clashes between workers and the police.

Rosa Luxemburg continued to protest against Germany's involvement in the war and on the 19th February, 1915, she was arrested. As a political prisoner she was allowed books and writing materials. With the help of Mathilde Jacob she was able to smuggle out articles and pamphlets she had written to Franz Mehring. In April 1915, Mehring published some of this material in a new journal, Die Internationale.

Other contributors included Clara Zetkin, August Thalheimer, Bertha Thalheimer, Käte Duncker and Heinrich Ströbel. The journal included articles by Mehring on the attitude of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels to the problem of war and Zetkin dealt with the position of women in wartime. The main objective of the journal was to criticise the official policy of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) towards the First World War.

Over the next few months members of this group were arrested for their anti-war activities and spent several short spells in prison. This included Ernest Meyer, Wilhelm Pieck and Hugo Eberlein. Other activists included Leo Jogiches, Paul Levi, Julian Marchlewski and Hermann Duncker. On the release of Luxemburg in February 1916, it was decided to establish an underground political organization called Spartakusbund (Spartacus League). The Spartacus League publicized its views in its illegal newspaper, Spartakusbriefe. Like the Bolsheviks in Russia, they argued that socialists should turn this nationalist conflict into a revolutionary war.

The group published an attack on all European socialist parties (except the Independent Labour Party): "By their vote for war credits and by their proclamation of national unity, the official leaderships of the socialist parties in Germany, France and England (with the exception of the Independent Labour Party) have reinforced imperialism, induced the masses of the people to suffer patiently the misery and horrors of the war, contributed to the unleashing, without restraint, of imperialist frenzy, to the prolongation of the massacre and the increase in the number of its victims, and assumed their share in the responsibility for the war itself and for its consequences."

Eugen Levine was one of the first people to join the Spartacus League. He had been disturbed by the "new wave of national prejudice and chauvinism". His wife, Rosa Levine-Meyer, was shocked when he stated that the war would last "at least eighteen months or two years". This upset his mother who had been convinced by government propaganda that "the war would end by Christmas". Levine told Rosa that the "war would be accompanied by a severe world crisis and revolutionary shocks". He added that during a war "it is easier to convert thousands of workers than one single well-meaning intellectual".

On 1st May, 1916, Rosa Luxemburg, organised a anti-war demonstration on Potsdamer Platz in Berlin. It was a great success and by eight o'clock in the morning around 10,000 people assembled in the square. The police charged at Karl Liebknecht who was about to speak to the large crowd. "For two hours after Liebknecht's arrest masses of people swirled around Potsdamer Platz and the neighbouring streets, and there were many scuffles with the police. For the first time since the beginning of the war open resistance to it had appeared on the streets of the capital."

As a member of the Reichstag, Liebknecht had parliamentary immunity from prosecution. When the military judicial authorities demanded that this immunity was removed, the Reichstag agreed and he was placed on trial. On 28th June 1916, Liebknecht was sentenced to two years and six months hard labour. The day Liebknecht was sentenced, 55,000 munitions workers went on strike. The government responded by arresting trade union leaders and having them conscripted into the German Army.

Luxemburg responded by publishing a handbill defending Liebknecht and accusing members of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) who had removed his parliamentary immunity as being "political dogs". She claimed that: "A dog is someone who licks the boots of the master who has dealt him kicks for decades. A dog is someone who gaily wags his tail in the muzzle of martial law and looks straight into the eyes of the lords of the military dictatorship while softly whining for mercy... A dog is someone who, at his government's command, abjures, slobbers, and tramples down into the muck the whole history of his party and everything it has held sacred for a generation."

Rosa Luxemburg was re-arrested on 10th July, 1916. So also was the seventy-year-old Franz Mehring, Ernest Meyer and Julian Marchlewski. Leo Jogiches now became the leader of the Spartacus League and the editor of its newspaper, Spartakusbriefe. Luxemburg, wrote regularly for each edition, sometimes writing three-quarters of a whole issue. She also worked on her book, Introduction to Economics.

In April 1917 Clara Zetkin left the Spartacus League and along with other left-wing members of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) formed the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD). Members included Kurt Eisner, Karl Kautsky, Emil Barth, Julius Leber, Ernst Toller, Ernst Thälmann, Rudolf Breitscheild, Emil Eichhorn, Kurt Rosenfeld, Ernst Torgler and Rudolf Hilferding.

The German government of Max von Baden asked President Woodrow Wilson for a ceasefire on 4th October, 1918. "It was made clear by both the Germans and Austrians that this was not a surrender, not even an offer of armistice terms, but an attempt to end the war without any preconditions that might be harmful to Germany or Austria." This was rejected and the fighting continued. On 6th October, it was announced that Karl Liebknecht, who was still in prison, demanded an end to the monarchy and the setting up of Soviets in Germany.

Although defeat looked certain, Admiral Franz von Hipper and Admiral Reinhard Scheer began plans to dispatch the Imperial Fleet for a last battle against the Royal Navy in the southern North Sea. The two admirals sought to lead this military action on their own initiative, without authorization. They hoped to inflict as much damage as possible on the British navy, to achieve a better bargaining position for Germany regardless of the cost to the navy. Hipper wrote "As to a battle for the honor of the fleet in this war, even if it were a death battle, it would be the foundation for a new German fleet...such a fleet would be out of the question in the event of a dishonorable peace."

The naval order of 24th October 1918, and the preparations to sail triggered a mutiny among the affected sailors. By the evening of 4th November, Kiel was firmly in the hands of about 40,000 rebellious sailors, soldiers and workers. "News of the events in Keil soon travelled to other nearby ports. In the next 48 hours there were demonstrations and general strikes in Cuxhaven and Wilhelmshaven. Workers' and sailors' councils were elected and held effective power."

By the 8th November, workers councils took power in virtually every major town and city in Germany. This included Bremen, Cologne, Munich, Rostock, Leipzig, Dresden, Frankfurt, Stuttgart and Nuremberg. Theodor Wolff, writing in the Berliner Tageblatt: "News is coming in from all over the country of the progress of the revolution. All the people who made such a show of their loyalty to the Kaiser are lying low. Not one is moving a finger in defence of the monarchy. Everywhere soldiers are quitting the barracks."

Chancellor, Max von Baden, decided to hand over power over to Friedrich Ebert, the leader of the German Social Democrat Party. At a public meeting, one of Ebert's most loyal supporters, Philipp Scheidemann, finished his speech with the words: "Long live the German Republic!" He was immediately attacked by Ebert, who was still a strong believer in the monarchy: "You have no right to proclaim the republic."

Karl Liebknecht, who had been released from prison on 23rd October, climbed to a balcony in the Imperial Palace and made a speech: "The day of Liberty has dawned. I proclaim the free socialist republic of all Germans. We extend our hand to them and ask them to complete the world revolution. Those of you who want the world revolution, raise your hands." It is claimed that thousands of hands rose up in support of Liebknecht.

The Social Democratic Party press, fearing the opposition of the left-wing and anti-war Spartacus League, proudly trumpeted their achievements: "The revolution has been brilliantly carried through... the solidarity of proletarian action has smashed all opposition. Total victory all along the line. A victory made possible because of the unity and determination of all who wear the workers' shirt."

Friedrich Ebert established the Council of the People's Deputies, a provisional government consisting of three delegates from the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and three from the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD). Liebknecht was offered a place in the government but he refused, claiming that he would be a prisoner of the non-revolutionary majority. A few days later Ebert announced elections for a Constituent Assembly to take place on 19th January, 1918. Under the new constitution all men and women over the age of 20 had the vote.

As a believer in democracy, Rosa Luxemburg assumed that her party, the Spartacus League, would contest these universal, democratic elections. However, other members were being influenced by the fact that Lenin had dispersed by force of arms a democratically elected Constituent Assembly in Russia. Luxemburg rejected this approach and wrote in the party newspaper: "The Spartacus League will never take over governmental power in any other way than through the clear, unambiguous will of the great majority of the proletarian masses in all Germany, never except by virtue of their conscious assent to the views, aims, and fighting methods of the Spartacus League."

Friedrich Ebert decided to destroy the Spartacus League in Berlin who had attempted to gain power by force. He made contact with General Wilhelm Groener, who as First Quartermaster General, had played an important role in the retreat and demobilization of the German armies. According to William L. Shirer, the SDP leader and the "second-in-command of the German Army made a pact which, though it would not be publicly known for many years, was to determine the nation's fate. Ebert agreed to put down anarchy and Bolshevism and maintain the Army in all its tradition. Groener thereupon pledged the support of the Army in helping the new government establish itself and carry out its aims."

On the 5th January, Ebert called in the German Army and the Freikorps to bring an end to the rebellion. Groener later testified that his aim in reaching accommodation with Ebert was to "win a share of power in the new state for the army and the officer corps... to preserve the best and strongest elements of old Prussia". Ebert was motivated by his fear of the Spartacus League and was willing to use "the armed power of the far-right to impose the government's will upon recalcitrant workers, irrespective of the long-term effects of such a policy on the stability of parliamentary democracy".

The soldiers who entered Berlin were armed with machine-guns and armoured cars and demonstrators were killed in their hundreds. Artillery was used to blow the front off the police headquarters before Eichhorn's men abandoned resistance. "Little quarter was given to its defenders, who were shot down where they were found. Only a few managed to escape across the roofs."

By 13th January, 1919 the rebellion had been crushed and most of its leaders were arrested. This included Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, who refused to flee the city, and were captured on 16th January and taken to the Freikorps headquarters. "After questioning, Liebknecht was taken from the building, knocked half conscious with a rifle butt and then driven to the Tiergarten where he was killed. Rosa was taken out shortly afterwards, her skull smashed in and then she too was driven off, shot through the head and thrown into the canal."

Clara Zetkin was one of twenty-two members of the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) elected to the Constituent Assembly. The German Social Democrat Party won 163 of a total of 421, and dominated the new national government. On 29th January 1919, she was the first woman to speak in a German parliament. In the speech she delivered an attack on Friedrich Ebert and his government for the way he had dealt with the Spartacus League.

Leo Jogiches was executed on 10th March, 1919. Clara Zetkin wrote to Lenin on 8th April: "The murder of Karl (Liebknecht) and especially Rosa (Luxemburg) was a terrible blow. Leo's death has taken from me the last of the small group in which we have been fighting together... Of the four who first protested against the world war and fought for the revolution I am now the only one alive and in Germany I feel completely orphaned."

In May, 1919, Clara Zetkin, wrote an article, about her long-term colleague, Rosa Luxemburg, who had been murdered by the Freikorps. "Rosa Luxemburg the socialist idea was a dominating and powerful passion of both mind and heart, a consuming and creative passion. To prepare for the revolution, to pave the way for socialism - this was the task and the one great ambition of this exceptional woman. To experience the revolution, to fight in its battles - this was her highest happiness. With will-power, selflessness and devotion, for which words are too weak, she engaged her whole being and everything she had to offer for socialism. She sacrificed herself to the cause, not only in her death, but daily and hourly in the work and the struggle of many years. She was the sword, the flame of revolution."

In January, 1919 the Spartacus League changed its name to the German Communist Party (KPD). Later that year she switched from the USPD to the KPD. Other members included Paul Levi, Willie Munzenberg, Ernst Toller, Walther Ulbricht, Julian Marchlewski, Ernst Thälmann, Hermann Duncker, Hugo Eberlein, Paul Frölich, Wilhelm Pieck, Franz Mehring, and Ernest Meyer. Levi's moderate approach to communism increased the size of the party and in the 1924 elections they won 62 seats in the Reichstag.

Clara Zetkin served on the Central Committee of the KPD. She was also appointed to the executive committee of Comintern which meant she spent long period in the Soviet Union. A life-long anti-racist, Zetkin took part in the international protests against Jim Crow laws in the United States. She also campaigned against the conviction of the Scotsboro Boys.

In March, 1929, Clara Zetkin wrote to Nikolai Bukharin complaining about the way the KPD was being run. "I feel completely alone and alien in this body, which has changed from being a living political organism into a dead mechanism, which on one side swallows orders in the Russian language and on the other spits them out in various languages, a mechanism which turns the mighty world historical meaning and content of the Russian revolution into the rules of the game for Pickwick Clubs."

In 1932, Zetkin, although seventy-five years old, was once again elected to the Reichstag. As the oldest member she was entitled to open the parliament's first session. Zetkin took the opportunity to make a long speech where she denounced the policies of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party. "Motivated by imperialist cravings, they bring Germany into aimless, amateurish vacillations between clumsily currying favour with and sabre-rattling against the Great Powers of the Versailles Treaty, which will bring this country into greater dependence upon them. They also damage relations with the Soviet Union - the state that, through its honest policies of peace and its economic ascendance, stands behind the German working population."

Zetkin condemned the terror tactics employed during the election campaign. "The presidential cabinet bears a great burden of guilt. It is fully responsible for the murders of the last few weeks, murders for which it is fully responsible through its abolishing the ban on uniforms for the National Socialist Storm Troopers and by its open patronage of Fascist civil-war troops. In vain, it seeks to hide its political and moral guilt through quarrels with its allies about the division of power in the state; the blood that has been spilled will forever link it to the Fascist murders."