On this day on 15th November

On this day in 1861 Margaret Haley was born in Joliet, Illinois. Haley became a teacher in Chicago in 1876. An early member of the Chicago Teachers' Federation she became a full-time official in 1901.

In 1903 Haley joined with Mary Kenney O'Sullivan, Jane Addams, Mary McDowell, Helen Marot, Agnes Nestor, Florence Kelley and Sophonisba Breckinridge to form the Women's Trade Union League.

Haley was also president of the National Federation of Teachers and used this organization to help develop the more important National Education Association. Haley led a long campaign for state pensions for teachers and this was successfully introduced in Illinois in 1907.

Haley became an organizer with the American Federation of Teachers when it was established in 1916. She also wrote and published the Margaret Haley Bulletin (1915-31).

Margaret Haley died in Chicago on 5th January, 1939.

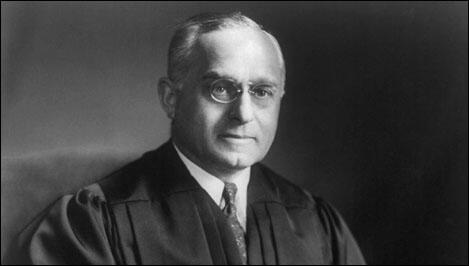

On this day in 1882 Felix Frankfurter was born in Vienna, Austria, on 15th November, 1882. Twelve years later the family emigrated to the United States. After graduating from New York City College in 1902, Frankfurter entered Harvard Law School. He studying for his degree he also edited the Harvard Law Review.

In 1906 Henry Stimson, a New York City attorney, recruited Frankfurter as his assistant. When President William Howard Taft appointed Stimson as his secretary of war in 1911, he took Frankfurter along as law officer of the Bureau of Insular Affairs. Frankfurter became involved in the Tom Mooney case. According to Robert Lovett: "Felix Frankfurter, on a mission to examine and report to President Wilson on labor difficulties in the West, saw through the plot and warned the president of the danger in the execution of an innocent man whose fate was exciting workers all over the world. After commutation of the sentence to imprisonment for life, the long struggle began. One by one the folds of perjury were peeled away until the nucleus of the noxious growth was reached."

When Stimson lost office in 1914, Frankfurter returned to the Harvard Law School as professor of administrative law. In 1918 he decided to spend time in London. His friend, Graham Wallas, a tutor at the London School of Economics, asked one of his students, Ella Winter, if she wanted to work for him: "A good friend of mine has come to London on a highly confidential mission and asks me to suggest someone to help him... Felix Frankfurter is a professor at the Harvard Law School and Chairman of the War Labour Policies Board in America, and is here to learn what he can from England's experience. Would you like to work for him."

Winter met Frankfurter at Claridge's Hotel and wrote about it in her autobiography, And Not to Yield (1963): "He was a short, mercurial man, with glasses and a cleft chin, who smiled, talked in quick staccato phrases, flung questions at one, while attending to twenty other matters at the same time. His smile showed a row of dazzling teeth. Even at rest he seemed in motion. He was warm, friendly, trusting, and assumed so immediately and unquestionably that I would do this job, indeed that I could do anything, that doubt, fear, hesitation vanished."

Frankfurther acquired a reputation for holding progressive political views. A founder member of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) he criticised the Tennessee Anti-Evolution Law. He also joined forces with John Dos Passos, Alice Hamilton, Paul Kellog, Jane Addams, Heywood Broun, Eugene Lyons, William Patterson, Upton Sinclair, Dorothy Parker, Ruth Hale, Ben Shahn, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Susan Gaspell, Mary Heaton Vorse, John Howard Lawson, Freda Kirchway, Floyd Dell, Katherine Anne Porter, Michael Gold, Bertrand Russell, John Galsworthy, Arnold Bennett, George Bernard Shaw and H. G. Wells in the campaign to overturn the death sentence imposed on Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti.

Frankfurter gave legal advice to Franklin D. Roosevelt when he served as governor of New York (1929-1932). When Roosevelt became president he often consulted Frankfurter about the legal implication of his New Deal legislation. He also arranged for some of his former talented students, including Thomas Corcoran and Ben Cohen to help draft legislation. Hugh Johnson described Frankfurter as "the most influential single individual in the United States". Frances Perkins, the Secretary of Labor, admitted in her autobiography, that she often asked Frankfurter for advice on drafting legislation.

Frankfurter explained in a letter to Walter Lippmann that he supported Roosevelt's gradualism: "Mine being a pragmatic temperament, all my scepticism and discontent with the present order and tendencies have not carried me over to a new scheme of society, whether socialism or communism... Those of us who, by temperament or habit of conviction, believe that we do not have to make a sudden and drastic break with the past but by gradual, successive, although large, modifications may slowly evolve out of this profit-mad society, may find all our hopes and strivings indeed reduced to a house of cards."

William E. Leuchtenburg, the author of The FDR Years: Roosevelt and his Legacy (1995), has pointed out that Roosevelt was criticised for his relationship with people like Frankfurter: "In the New Deal years, the seats of power were no longer monopolized by white Anglo-Saxon Protestants. Commentators made much of the closeness to FDR of Jews such as his counselor and subsequently Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter and his chief speechwriter Samuel Rosenman."

In 1939 Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Felix Frankfurter as a Supreme Court justice. Frankfurter took a strong stand on individual civil rights and this led to him being condemned as an "extreme liberal". However he upset many radicals by refusing to protect socialists and communists blacklisted during what became known as McCarthyism. His long-term friend, Alice Hamilton, asked him: "Why are we the only western country that lives in terror of native Communists. All the European countries have open and above-board political Communist parties some even have members of Parliament or whatever, and they do not have Un-Dutch Activities Committee. Look at the contrast between the English treatment of Klaus Fuchs and our treatment of the Rosenbergs. Fuchs is a scientist (which Rosenberg was not) he gave valuable atomic secrets to the Russians (Urey testified that Rosenberg did not know enough to do that) he confessed (the Rosenbergs refused to, though offered their lives as reward) Fuchs acted during the war, the Rosenbergs during peace."

On this day in 1891 Erwin Rommel, was born. In October 1935 Rommel was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel and began teaching at the Potsdam War Academy. An excellent teacher, Rommel's lectures were published as a book entitled, Infantry in the Attack in 1935. To his surprise, it was a bestseller in Nazi Germany and the Swiss Army adopted it as a training manual. The book was read by Adolf Hitler. Greatly impressed by Rommel's ideas Hitler invited him to be commander of his personal bodyguard at the 1936 Nuremberg Party Rally.

General Major Rommel was given command of the 7th Panzer Division that invaded France in May, 1940. Rommel's troops moved faster and farther than any other army in military history. Mark M. Boatner III has argued: "His first dramatic triumph was on the Meuse just north of Dinant, where he defied conventional military wisdom and made the assault crossing without waiting for large infantry formations to catch up. Rommel's troops became known as the Ghost or Phantom division, moving faster and farther than any other in modern military history, appearing out of nowhere, spreading confusion and the consequent terror. After racing across Flanders to the Channel, Rommel turned south and received the surrender of Cherbourg on 19 June 1940."

When Benito Mussolini asked for help in North Africa, Adolf Hitler sent Rommel to command the new Deutsches Afrika Korps. He began his command on 6th February 1941 and six days later reached Tripoli. Rommel was concerned by what he found: "I had already decided that in view of the tenseness of the situation and the sluggishness of the Italian command, to depart from my instructions... and to take the command at the front into my hands as soon as possible, at the latest after the arrival of the first German troops. General von Rintelen, to whom I had given a hint of my intention in Rome, had advised me against it, for, as he put it, that was the way to lose both honour and reputation."

Rommel's first offensive (24th May - 30th May) has been described as a "masterpiece of desert warfare by a general with no experience in this field". The man who became known as the "Desert Fox" pushed 1,500 miles to the Egyptian border. General Archibald Wavell attempted a counter-attack on 17th June, 1941, but his troops were halted at Halfaya Pass. Although Wavell held in high esteem by General Alan Brooke, the Chief of General Staff, Winston Churchill had lost confidence in him and replaced him by General Claude Auchinleck.

Basil Liddell Hart, the author of The Other Side of the Hill (1951) has argued: "From 1941 onwards the names of all other German generals came to be overshadowed by that of Erwin Rommel. He had the most startling rise of any-from colonel to field-marshal. He was an outsider, in a double sense - as he had not qualified for high position in the hierarchy of the General Staff, while he long performed in a theatre outside Europe.... While Rommel owed much to Hitler's favour, it was testimony to his own dynamic personality that he first impressed himself on Hitler's mind, and then impressed his British opponents so deeply as to magnify his fame beyond Hitler's calculation."

On 21st November 1943 Rommel was sent to France and placed in charge of coastal defences. He had the responsibility of examining all possible invasion areas from Denmark to the Alps. General Hans Speidel, Rommels's Chief of Staff, has argued that at the time, the Normandy coast "was practically unfortified when Marshal Rommel took over command." Rommel ordered four belts of "foreshore obstacles" that would be "effective at all tide conditions" to be installed. Records show that by 20th May 1944 more than 4,000,000 land mines were laid on the coast.

A group of conspirators that included Friedrich Olbricht, Henning von Tresckow, Friedrich Olbricht, Werner von Haeften, Fabian Schlabrendorff, Claus von Stauffenberg, Carl Goerdeler, Julius Leber, Ulrich Hassell, Hans Oster, Peter von Wartenburg, Fabian Schlabrendorff, Ludwig Beck and Erwin von Witzleben, developed a scheme to overthrow the Nazi government. After the assassination of Adolf Hitler, Hermann Goering and Heinrich Himmler it was planned for troops in Berlin to seize key government buildings, telephone and signal centres and radio stations.

The conspirators approached Erwin Rommel and invited him to take part in the plot against Hitler and offered him the post of Chief of State. Joachim Fest, the author of Plotting Hitler's Death (1997) has argued that "Rommel was extremely popular with the general public, and though he was certainly not an enemy of the regime, the insurgents hoped that he might join them if the circumstances were right. Rommel's participation would have helped prevent the creation of another stab-in-the-back legend, a concern that had so preoccupied the conspirators." Rommel refused the offer as he opposed the projected assassination attempt on Hitler's life on the grounds that this action would only create a martyr. He suggested that it was better to place him on trial to reveal his crimes to the nation.

On 17th July, 1944, after the Allied invasion of Normandy, Rommel was critically wounded in the head by shells from an enemy fighter-bomber. His car capsized and he was thrown out, fracturing his skull. Rommel was not expected to live through the night, he nevertheless survived and eventually returned home to Herrlingen, a village in his native Swabia, near Ulm, where he had moved his family in late 1943. Meanwhile, the conspiracy to kill Hitler continued.

On 20th July, 1944, Claus von Stauffenberg attended a conference attended by Hitler on 20th July, 1944. Alan Bullock, the author of Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) later explained: "He (Stauffenberg) brought his papers with him in a brief-case in which he had concealed the bomb fitted with a device for exploding it ten minutes after the mechanism had been started. The conference was already proceeding with a report on the East Front when Keitel took Stauffenberg in and presented him to Hitler. Twenty-four men were grouped round a large, heavy oak table on which were spread out a number of maps. Neither Himmler nor Goring was present. The Fuhrer himself was standing towards the middle of one of the long sides of the table, constantly leaning over the table to look at the maps, with Keitel and Jodl on his left. Stauffenberg took up a place near Hitler on his right, next to a Colonel Brandt. He placed his brief-case under the table, having started the fuse before he came in, and then left the room unobtrusively on the excuse of a telephone call to Berlin. He had been gone only a minute or two when, at 12.42 p.m., a loud explosion shattered the room, blowing out the walls and the roof, and setting fire to the debris which crashed down on those inside."

Joachim Fest later pointed out: "Suddenly, as witnesses later recounted, a deafening crack shattered the midday quiet, and a bluish-yellow flame rocketed skyward... A dark plume of smoke rose and hung in the air over the wreckage of the briefing barracks. Shards of glass, wood, and fiberboard swirled about, and scorched pieces of paper and insulation rained down... When the bomb exploded, twenty-four people were in the conference room. All were hurled to the ground, some with their hair in flames." The bomb killed four men in the hut: General Rudolf Schmundt, General Günther Korten, Colonel Heinz Brandt and stenographer Heinz Berger. Hitler's right arm was badly injured but he survived what became known as the July Plot.

The plan was for Ludwig Beck, Erwin von Witzleben and Erich Fromm to take control of the German Army. This idea was abandoned when it became known that Adolf Hitler had survived the assassination attempt. In an attempt to protect himself, Fromm organized the execution of Stauffenberg along with three other conspirators, Friedrich Olbricht and Werner von Haeften, in the courtyard of the War Ministry. It was later reported the Stauffenberg died shouting "Long live free Germany".

Over the next few months most of the group including Wilhelm Canaris, Carl Goerdeler, Julius Leber, Ulrich Hassell, Hans Oster, Peter von Wartenburg, Henning von Tresckow, Ludwig Beck, Erwin von Witzleben and Erich Fromm were either executed or committed suicide. An eyewitness later reported: "Imagine a room with a low ceiling and whitewashed walls. Below the ceiling a rail was fixed. From it hung six big hooks, like those butchers use to hang their meat. In one corner stood a movie camera. Reflectors cast a dazzling, blinding light. At the wall there was a small table with a bottle of cognac and glasses for the witnesses of the execution. The hangman wore a permanent leer, and made jokes unceasingly. The camera worked uninterruptedly, for Hitler wanted to see and hear how his enemies died."

One of the conspirators, before he died in agony on a meat hook, blurted out the name of General Erwin Rommel to his tormentors. Rommel was so popular that Hitler was unwilling to have him executed for treason. Hitler sent two officers to Rommel's home at Herrlingen on 14th October, 1944. His son, Manfred Rommel later recalled that his father told him: "I have just had to tell your mother that I shall be dead in a quarter of an hour. Hitler is charging me with high treason. In view of my services in Africa I am to have the chance of dying by poison. The two generals have brought it with them. Its fatal in three seconds. If I accept, none of the usual steps will be taken against my family. I'd be given a state funeral. It's all been prepared to the last detail. In a quarter of an hour you will receive a call from the hospital in Ulm to say that I've had a brain seizure on the way to a conference." Rommel committed suicide and was buried with full military honours.

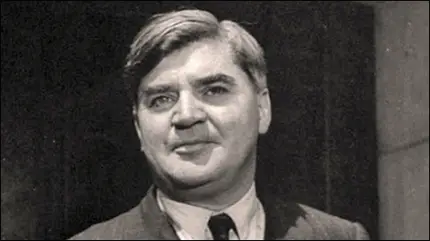

On this day in 1897 Aneurin Bevan was born in Tredegar. At the beginning of the Second World War Bevan became the foremost parliamentary critic of Neville Chamberlain and his government. "If this war is to be won by a collapse in Germany, it can only be done by first breaking down the moral authority of the National Government... If we have no confidence in the Chamberlain Government why should the German worker?"

Chamberlain decided to resign and on 10th May, 1940, George VI appointed Winston Churchill as prime minister. Churchill formed a coalition government and placed leaders of the Labour Party such as Clement Attlee (Deputy Prime Minister), Ernest Bevin (Minister of Labour), Herbert Morrison (Home Secretary), Stafford Cripps (Minister of Aircraft Production), Arthur Greenwood (Minister without Portfolio) and Hugh Dalton (Minister of Economic Warfare) in key positions. He also brought in another long-time opponent of Chamberlain, Anthony Eden, as his secretary of state for war.

Bevan condemned Churchill's decision to keep leading appeasers such as Neville Chamberlain (Lord President of the Council), Lord Halifax (Foreign Secretary), Kingsley Wood (Chancellor of the Exchequer) and John Simon (Lord High Chancellor) in senior positions in the government. He argued that Bevin and Morrison were the right men for their posts "yet Labour was only being allowed to put petrol in the car: the Tories still held the steering wheel."

Once Churchill was in power, Bevan used his influence as editor of Tribune and the leader of the left-wing MPs in the House of Commons, to shape government policies. Bevan opposed the heavy censorship imposed on radio and newspapers and wartime Regulation 18B that gave the Home Secretary the powers to lock up citizens without trial. When the government banned the Daily Worker he argued that the newspaper was "detestable but harmless" and the real reason for its suppression was that it was "intended to serve as an instrument of intimidation against the Press as a whole". (58)

John Campbell, the author of Nye Bevan and the Mirage of British Socialism (1987) has argued: "There was a lot of fine talk about democracy during the war and a good deal of national self-congratulation that the forms of parliamentary government were maintained; but after the formation of the Coalition in May 1940 there was no regular opposition in the House of Commons except that offered by a few maverick malcontents of whom Bevan was increasingly the most prominent and by far the most consistent." (59)

Bevan believed that the Second World War would give Britain the opportunity to create a new society. He often quoted Karl Marx who had said in 1885: "The redeeming feature of war is that it puts a nation to the test. As exposure to the atmosphere reduces all mummies to instant dissolution, so war passes supreme judgment upon social systems that have outlived their vitality." At the beginning of the 1945 General Election campaign Bevan told his audience: "We have been the dreamers, we have been the sufferers, now we are the builders. We enter this campaign at this general election, not merely to get rid of the Tory majority. We want the complete political extinction of the Tory Party."

In its manifesto, Let us Face the Future, it made clear that "the Labour Party is a Socialist Party, and proud of it. Its ultimate purpose at home is the establishment of the Socialist Commonwealth of Great Britain - free, democratic, efficient, progressive, public-spirited, its material resources organised in the service of the British people.... Housing will be one of the greatest and one of the earliest tests of a Government's real determination to put the nation first. Labour's pledge is firm and direct - it will proceed with a housing programme with the maximum practical speed until every family in this island has a good standard of accommodation. That may well mean centralising and pooling of building materials and components by the State, together with price control. If that is necessary to get the houses as it was necessary to get the guns and planes, Labour is ready."

The manifesto argued for the state takeover of certain branches of the economy - the Bank of England, coal mines, electricity and gas, railways, and iron and steel. This reflected some of the measures passed by the Labour Conference in December 1944. However, some left-wing commentators pointed out that the "nationalisation measures were justified on grounds of economic efficiency, not as a means of shifting the balance between labour and capital."

The document made it clear that if elected it would pass legislation to protect the working-class: "The Labour Party stands for freedom - for freedom of worship, freedom of speech, freedom of the Press. The Labour Party will see to it that we keep and enlarge these freedoms, and that we enjoy again the personal civil liberties we have, of our own free will, sacrificed to win the war. The freedom of the Trade Unions, denied by the Trade Disputes and Trade Unions Act, 1927, must also be restored. But there are certain so-called freedoms that Labour will not tolerate: freedom to exploit other people; freedom to pay poor wages and to push up prices for selfish profit; freedom to deprive the people of the means of living full, happy, healthy lives".

The Labour Party also stated its commitment to a National Health Service: "By good food and good homes, much avoidable ill-health can be prevented. In addition the best health services should be available free for all. Money must no longer be the passport to the best treatment. In the new National Health Service there should be health centres where the people may get the best that modern science can offer, more and better hospitals, and proper conditions for our doctors and nurses. More research is required into the causes of disease and the ways to prevent and cure it. Labour will work specially for the care of Britain's mothers and their children - children's allowances and school medical and feeding services, better maternity and child welfare services. A healthy family life must be fully ensured and parenthood must not be penalised if the population of Britain is to be prevented from dwindling."

When the poll closed the ballot boxes were sealed for three weeks to allow time for servicemen's votes (1.7 million) to be returned for the count on 26th July. It was a high turnout with 72.8% of the electorate voting. With almost 12 million votes, Labour had 47.8% of the vote to 39.8% for the Conservatives. Labour made 179 gains from the Tories, winning 393 seats to 213. The 12.0% national swing from the Conservatives to Labour, remains the largest ever achieved in a British general election. It came as a surprise that Winston Churchill, who was considered to be the most important figure in winning the war, suffered a landslide defeat. Harold Macmillan commented: "It was not Churchill who lost the 1945 election; it was the ghost of Neville Chamberlain."

Henry (Chips) Channon recorded in his diary what happened on the first day of the new Parliament: "I went to Westminster to see the new Parliament assemble, and never have I seen such a dreary lot of people. I took my place on the Opposition side, the Chamber was packed and uncomfortable, and there was an atmosphere of tenseness and even bitterness. Winston staged his entry well, and was given the most rousing cheer of his career, and the Conservatives sang 'For He's a Jolly Good Fellow'. Perhaps this was an error in taste, though the Socialists went one further, and burst into the 'Red Flag' singing it lustily; I thought that Herbert Morrison and one or two others looked uncomfortable."

Clement Attlee, Herbert Morrison and Ernest Bevin, the senior figures in the government, were all on the right of the party. The new intake of MPs included far fewer from working-class backgrounds. According to one historian, "with apparent satisfaction the new prime minister noted that he had appointed no fewer than twenty-eight public school boys, including seven Etonians, five Haileyburians and four Winchester men, to the government."

The most significant figure on the left was Aneurin Bevan. He argued for a comprehensive programme of nationalisation as without state control, there could be no true socialism because there could be no planning: "In practice it is impossible for the modern State to maintain an independent control over the decisions of big business. When the State extends its control over big business, big business moves in to control the State. The political decisions of the State become so important a part of the business transactions of the combines that is the law of their survival that those decisions should suit the needs of profit-making. The State ceases to be the umpire. It becomes the prize."

After the 1945 General Election, Clement Attlee, the new Labour Prime Minister, appointed Aneurin Bevan as Minister of Health. In 1946 Parliament passed the revolutionary National Insurance Act. It instituted a comprehensive state health service, effective from 5th July 1948. The Act provided for compulsory contributions for unemployment, sickness, maternity and widows' benefits and old age pensions from employers and employees, with the government funding the balance.

The government also announced plans for a National Health Service that would be, "free to all who want to use it." Some members of the medical profession opposed the government's plans. Between 1946 and its introduction in 1948, the British Medical Association (BMA) mounted a vigorous campaign against this proposed legislation. In one survey of doctors carried out in 1948, the BMA claimed that only 4,734 doctors out of the 45,148 polled, were in favour of a National Health Service.

The right-wing national press was opposed to the idea of a National Health Service. The Daily Sketch reported: "The State medical service is part of the Socialist plot to convert Great Britain into a National Socialist economy. The doctors' stand is the first effective revolt of the professional classes against Socialist tyranny. There is nothing that Bevan or any other Socialist can do about it in the shape of Hitlerian coercion."

Winston Churchill led the attack on Bevan. In one debate in the House of Commons he argued that unless Bevan "changes his policy and methods and moves without the slightest delay, he will be as great a curse to his country in time of peace as he was a squalid nuisance in time of war." The Conservative Party voted against the measure. The Tory ammendment stated that it "declines to give a Third Reading to a Bill which discourages voluntary effort and association; mutilates the structure of local government; dangerously increases minisaterial power and patronage; approppriates trust funds and benefactions in contempt of the wishes of donors and subscribers; and undermines the freedom and independence of the medical profession to the detriment of the nation." However, on 2th July, 1946, the Third Reading was carried by 261 votes to 113. Michael Foot commented that the Conservatives had voted against the "most exciting and popular of the Government's measures a bare four months before it was to be introduced".

David Widgery, the author of The National Health: A Radical Perspective (1988) admitted that "the Act was bold in outline; a National Health Service entirely free at the time of use, financed out of general taxation and able to organise preventive medicine, research and paramedical aids on a national basis... Bevan himself was apparently well prepared to deal with conservative pressures, and he was quite prepared for the out-break of near-hysteria by doctors, skilfully orchestrated by Charles Hill of the BMA, who had endeared himself to the listening public during the war as the smooth-spoken, concerned Radio Doctor."

Between 1946 and its introduction in 1948, the British Medical Association (BMA), led by Charles Hill, mounted a vigorous campaign against this proposed legislation. In one survey of doctors carried out in 1948, the BMA claimed that only 4,734 doctors out of the 45,148 polled, were in favour of a National Health Service. One doctor was cheered at a BMA meeting for saying that the proposed NHS bill was "strongly suggestive" of what had been going in Nazi Germany.

By July 1948, Aneurin Bevan had guided the National Health Service Act safely through Parliament. The Government resolution was carried by 337 votes to 178. Niall Dickson has pointed out: "The UK's National Health Service (NHS) came into operation at midnight on the fourth of July 1948. It was the first time anywhere in the world that completely free healthcare was made available on the basis of citizenship rather than the payment of fees or insurance premiums... Life in Britain in the 30s and 40s was tough. Every year, thousands died of infectious diseases like pneumonia, meningitis, tuberculosis, diphtheria, and polio. Infant mortality - deaths of children before their first birthday - was around one in 20, and there was little the piecemeal healthcare system of the day could do to improve matters. Against such a background, it is difficult to overstate the impact of the introduction of the National Health Service (NHS). Although medical science was still at a basic stage, the NHS for the first time provided decent healthcare for all - and, at a stroke, transformed the lives of millions."

The Manchester Guardian commented on the passing of the National Health Service Act: "These two reforms have sometimes been greeted as a large installment of Socialism in this country. They are not strictly that, for many besides Socialists have contributed something to them. What they mark is rather an advance of the equalitarianism which has been the mainspring, though not the exclusive possession, of the British Labour movement. They are designed to offset as far as they can the inequalities that arise from the chances of life, to ensure that a "bad start" or a stroke of bad luck, illness or accident or loss of work, does not carry the heavy, often crippling, economic penalty it has carried in the past. It is important to realise the fundamental change in attitude which this implies, and its consequences for our social evolution."

In October 1950, Clement Attlee promoted Hugh Gaitskell to chancellor of the exchequer. Aneurin Bevan considered Gaitskell as hostile to the National Health Service and sent a letter to Attlee commenting: "I feel bound to tell you that for my part I think the appointment of Gaitskell to be a great mistake. I should have thought myself that it was essential to find out whether the holder of this great office would commend himself to the main elements and currents of opinion in the Party. After all, the policies which he will have to propound and carry out are bound to have the most profound and important repercussions throughout the movement."

One of Gaitskell's first tasks was to balance the budget. The National Insurance Act created the structure of the Welfare State and after the passing of the National Health Service Act in 1948, people in Britain were provided with free diagnosis and treatment of illness, at home or in hospital, as well as dental and ophthalmic services. Michael Foot, the author of Aneurin Bevan (1973) has argued: "On the afternoon of 10th April he (Hugh Gaitskell) presented his Budget, including the proposal to save £13 million - £30 million in a full year-by imposing charges on spectacles and on dentures supplied under the Health Service. And glancing over his shoulder at the benches behind him he had seemed to underline his resolve: having made up his mind, he said, a Chancellor 'should stick to it and not be moved by pressure of any kind, however insidious or well-intentioned'. Bevan did not take his accustomed seat on the Treasury bench, but listened to this part of the speech from behind the Speaker's chair, with Jennie Bevan by his side. A muffled cry of 'shame' from her was the only hostile demonstration Gaitskell received that afternoon."

The following day, Aneurin Bevan resigned from the government. In a speech he made in the House of Commons he explained why he had made this decision: "The Chancellor of the Exchequer in this year's Budget proposes to reduce the Health expenditure by £13 million - only £13 million out of £4,000 million... If he finds it necessary to mutilate, or begin to mutilate, the Health Services for £13 million out of £4,000 million, what will he do next year? Or are you next year going to take your stand on the upper denture? The lower half apparently does not matter, but the top half is sacrosanct. Is that right?... The Chancellor of the Exchequer is putting a financial ceiling on the Health Service. With rising prices the Health Service is squeezed between that artificial figure and rising prices. What is to be squeezed out next year? Is it the upper half? When that has been squeezed out and the same principle holds good, what do you squeeze out the year after? Prescriptions? Hospital charges? Where do you stop?"

Bevan went on to argue that this measure was undermining the Welfare State: "Friends, where are they going? Where am I going? I am where I always was. Those who live their lives in mountainous and rugged countries are always afraid of avalanches, and they know that avalanches start with the movement of a very small stone. First, the stone starts on a ridge between two valleys - one valley desolate and the other valley populous. The pebble starts, but nobody bothers about the pebble until it gains way, and soon the whole valley is overwhelmed. That is how the avalanche starts, that is the logic of the present situation, and that is the logic my right honourable friends cannot escape.... After all, the National Health Service was something of which we were all very proud, and even the Opposition were beginning to be proud of it. It only had to last a few more years to become a part of our traditions, and then the traditionalists would have claimed the credit for all of it. Why should we throw it away? In the Chancellor's Speech there was not one word of commendation for the Health Service - not one word. What is responsible for that?"

On this day in 1907 Claus von Stauffenberg was born in Germany. His father was the Privy Chamberlain to the Maximilian, the King of Bavaria, and the last Oberhofmarschall of the Kingdom of Württemberg. His mother was granddaughter of the Prussian general August Wilhelm Anton Graf von Gneisenau. The Stauffenberg family was one of the oldest and most distinguished aristocratic Catholic families of southern Germany.

In 1926 he joined the family's traditional regiment, the 17th Cavalry Regiment in Bamberg. Stauffenberg was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in 1930. His regiment eventually became part of the German 1st Light Division under General Erich Hoepner. According to his biographer, Louis L. Snyder: "A strikingly handsome young man, Claus was nicknamed the Bamberger Reiter because of his extraordinary resemblance to the famous thirteenth-century statue in the Cathedral of Bamberg."

Any sympathy he might have felt towards the regime withered, however, with the experience of Kristallnacht. According to Anton Gill, the author of An Honourable Defeat: A History of German Resistance to Hitler (1994) "Stauffenberg's character seems to have been completely free of any racism whatsoever. He was, however, a professional soldier and he had not yet become politicised. Thoughts harboured against the National Socialist government now had to be shelved as Germany sped towards war.

As a result of the Munich Agreement Stauffenberg's regiment moved into the Sudetenland. As this area contained nearly all Czechoslovakia's mountain fortifications, she was no longer able to defend herself against further aggression. Adolf Hitler ordered the German Army to enter Prague on 15 March 1939. Stauffenberg strongly disapproved of this action and feared it would result in an unnecessary war. He told a friend that "the fool is headed for war". Stauffenberg also believed it would take at least ten years to win the war.

In June, 1941, Stauffenberg took part in Operation Barbarossa. He was appalled by the atrocities committed by the Schutz Staffeinel (SS) in the Soviet Union. According to his friend, Major Joachim Kuhn, Stauffenberg told him in August 1942 that "They are shooting Jews in masses. These crimes must not be allowed to continue." Joachim Fest, the author of Plotting Hitler's Death (1997) has pointed out: "As a result of the massacres in the East, relations between Hitler and the officer corps, which had always been cool, despite a momentary reconciliation at the time of the great triumphs in France, began to deteriorate rapidly... It was at this time Stauffenberg resolved to do everything in his power to remove Hitler and overthrow the regime."

Stauffenberg was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel and sent to Africa to join the 10th Panzer Division as its Operations Officer in the General Staff. On 7th April 1943, Stauffenberg was wounded in the face, in both hands, and in the knee by fire from a low-flying Allied plane. According to one source: "He feared that he might lose his eyesight completely, but he kept one eye and lost his right hand, half the left hand, and part of his leg." Stauffenberg spent three months in a hospital in Munich, where his life was saved by the expert supervision of Dr. Ferdinand Sauerbruch.

After he recovered it was decided that it would be impossible to serve on the front line and in October, 1943, he was appointed as Chief of Staff in the General Army Office. His commanding officer was General Friedrich Olbricht, who had already joined with Henning von Tresckow, Fabin Schlabrendorff and Hans Oster in the development of Operation Valkyrie, a General Staff plan which was ostensibly to be used to put down an attempted SS coup, but was really going to be used against Adolf Hitler. Lieutenant-Colonel Stauffenberg joined the conspiracy that also included Ludwig Beck, Helmuth Stieff, Wilhelm Leuschner, Carl Langbehn, Erich Hoepner, Albrecht Metz von Quirnheim, Werner von Haeften, Ulrich Hassell, Friedrich Fromm, Carl Goerdeler, Julius Leber, Peter von Wartenburg, Erwin von Witzleben, Johannes Popitz and Jakob Kaiser.

The group was pleased by the arrival of Stauffenberg who brought new dynamism to the attempt to remove Hitler. Stauffenberg volunteered to be the man who would assassinate Hitler: "With the help of men on whom he could rely at the Führer's headquarters, in Berlin and in the German Army in the west, Stauffenberg hoped to push the reluctant Army leaders into action once Hitler had been killed. To make sure that this essential preliminary should not be lacking, Stauffenberg allotted the task of assassination to himself despite the handicap of his injuries. Stauffenberg's energy had put new life into the conspiracy, but the leading role he was playing also roused jealousies."

Claus von Stauffenberg decided to carry out the assassination himself. But before he took action he wanted to make sure he agreed with the type of government that would come into being. Conservatives such as Carl Goerdeler and Johannes Popitz wanted Field Marshal Erwin von Witzleben to become the new Chancellor. However, socialists in the group, such as Julius Leber and Wilhelm Leuschner, argued this would therefore become a military dictatorship. At a meeting on 15th May 1944, they had a strong disagreement over the future of a post-Hitler Germany.

Stauffenberg was highly critical of the conservatives led by Carl Goerdeler and was much closer to the socialist wing of the conspiracy around Julius Leber. Goerdeler later recalled: "Stauffenberg revealed himself as a cranky, obstinate fellow who wanted to play politics. I had many a row with him, but greatly esteemed him. He wanted to steer a dubious political course with the left-wing Socialists and the Communists, and gave me a bad time with his overwhelming egotism."

Peter Hoffmann has argued: "On Goerdeler's insistence he agreed that Goerdeler should be the main negotiator with Leber, Leuschner and their representatives. Goerdeler had already written a letter to Stauffenberg, transmitted through Kaiser, protesting against Stauffenberg negotiating independently with trade union leaders and socialists... This meant that Goerdeler should play the leading role in all non-military questions, as Beck was still insisting as late as July 1944. This he did not so much from suspicion of Stauffenberg as from aversion to exaggerated concentration of power. Moreover Stauffenberg was politically inexperienced; his views were vague; goodwill and idealism by themselves generally only do damage in politics. The fact that he was risking his life did not give Stauffenberg the right to claim power of political decision; Goerdeler and Beck were risking their lives too. The ability to murder Hitler was no adequate justification for assuming the role of political leader."

To carry out the assassination, it was necessary for Stauffenberg to have access to Adolf Hitler. One member of the group, General Friedrich Fromm was Commander in Chief of the Reserve Army. His was in charge of training and personnel replacement for combat divisions of the German Army and had regular meetings with Hitler. It was agreed that a close friend of General Rudolf Schmundt, Hitler's chief adjutant, should suggest that Stauffenberg should become chief of staff to General Fromm. According to Albert Speer, "Schmundt explained to me, Stauffenberg was considered one of the most dynamic and competent officers in the German army. Hitler himself would occasionally urge me to work closely and confidentially with Stauffenberg. In spite of his war injuries (he had lost an eye, his right hand, and two fingers of his left hand), Stauffenberg had preserved a youthful charm; he was curiously poetic and at the same time precise, thus showing the marks of the two major and seemingly incompatible educational influences upon him: the circle around the poet Stefan George and the General Staff. He and I would have hit it off even without Schmundt's recommendation."

On 1st July 1944 Stauffenberg was promoted to Colonel and became Chief of Staff to Fromm. Stauffenberg was now in a position where he would have regular meetings with Adolf Hitler. Fellow conspirator, Henning von Tresckow sent a message to Stauffenberg: "The assassination must be attempted, at any cost. Even should that fail, the attempt to seize power in the capital must be undertaken. We must prove to the world and to future generations that the men of the German Resistance movement dared to take the decisive step and to hazard their lives upon it. Compared with this, nothing else matters."

Stauffenberg attended his first meeting with Hitler on 6th July. He had a bomb with him but for reasons that to this day are not entirely clear, he did not try to kill Hitler. The generally accepted theory is that Stauffenberg was dissuaded from acting because neither Heinrich Himmler or Hermann Göring were present. Several conspirators, including General Ludwig Beck, wanted these two men killed at the same time as Hitler. The theory being that Göring and Himmler would take power after the death of Hitler.

On 11th July, Stauffenberg flew once more to Hitler's headquarters in Berchtesgaden. He had a bomb with him but did not set it off because Himmler and Göring were not at the meeting. According to Peter Hoffmann: "There was never any certainty that Himmler or Göring would be present at the briefing conferences; neither of them attended regularly. They were usually represented by their liaison officers who reported to them; they themselves came comparatively seldom. Sometimes Himmler and Göring had no personal contact with Hitler for weeks; at other times one of the other would attend several conferences with Hitler daily." Stauffenberg remained committed to trying to kill Hitler although he had little confidence he would be successful. On 14th July he was quoted as saying: "The worst thing is knowing that we cannot succeed and yet that we have to do it, for our country and our children."

Claus von Stauffenberg had another meeting with Adolf Hitler on 15th July. Although he had the bomb with him he did not take this opportunity to kill Hitler. The main reason was probably the difficulty he would have had in fusing his bomb. Since he only had three fingers on one hand he had to use a pair of pliers and this would certainly have been seen. It has been claimed that if he had bent down "to his briefcase and began to open it with his three fingers - someone would certainly have come to his assistance, lifted it on to the table and helped him take out the papers - impossible then to search round for the pliers, squeeze the fuse and put the briefcase back on the floor."

Stauffenberg needed help in his task and his adjutant, Werner von Haeften, agreed to help assassinate Hitler, when he told his brother, the diplomat, Hans-Bernd von Haeften, also a member of the conspiracy, he raised objections on religious grounds. For sometime he had become entangled in a web of philosophical and religious reflection. He asked Werner: "Are you absolutely sure this is your duty before God and our forefathers?" Werner replied that the act was justified because it would bring an end to the war and would therefore save the lives of many Germans.

Stauffenberg was now convinced that he was morally justified in taking this action. His religious and ethical beliefs led him to the conclusion that it was his duty to eliminate Hitler and his murderous regime by any means possible. Just before he left on his mission to kill Hitler he said: "It is now time that something was done. But he who has the courage to do something must do so in the knowledge that he will go down in German history as a traitor. If he does not do it, however, he will be a traitor to his conscience."

On 20th July, 1944, Stauffenberg and Haeften left Berlin to meet with Hitler at the Wolf' Lair. After a two-hour flight from Berlin, they landed at Rastenburg at 10.15. Stauffenberg had a briefing with Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, Chief of Armed Forces High Commandat, at 11.30, with the meeting with Hitler due to take place at 12.30. As soon as the meeting was over, Stauffenberg, met up with Haeften, who was carrying the two bombs in his briefcase. They then went into the toilet to set the time-fuses in the bombs. They only had time to prepare one bomb when they were interrupted by a junior officer who told them that the meeting with Hitler was about to start. Stauffenberg then made the fatal decision to place one of the bombs in his briefcase. "Had the second device, even without the charge being set, been placed in Stauffenberg's bag alone with the first, it would have been detonated by the explosion, more than doubling the effect. Almost certainly, in such an event, no one would have survived."

When he entered the wooden briefing hut, twenty-four senior officers were in assembled around a huge map table on two heavy oak supports. Stauffenberg had to elbow his way forward a little in order to get near enough to the table and he had to place the briefcase so that it was in no one's way. Despite all his efforts, however, he could only get to the right-hand corner of the table. After a few minutes, Stauffenberg excused himself, saying that he had to take a telephone call from Berlin. There was continual coming and going during the briefing conferences and this did not raise any suspicions.

Stauffenberg and Haeften went straight to a building about 200 hundred yards away consisting of bunkers and reinforced huts. Shortly afterwards, according to eyewitnesses: "A deafening crack shattered the midday quiet, and a bluish-yellow flame rocketed skyward... and a dark plume of smoke rose and hung in the air over the wreckage of the briefing barracks. Shards of glass, wood, and fiberboard swirled about, and scorched pieces of paper and insulation rained down."

Stauffenberg and Haeften observed a body covered with Hitler's cloak being carried out of the briefing hut on a stretcher and assumed he had been killed. They got into a car but luckily the alarm had not yet been given when they reached Guard Post 1. The Lieutenant in charge, who had heard the blast, stopped the car and asked to see their papers. Stauffenberg who was given immediate respect with his mutilations suffered on the front-line and his aristocratic commanding exterior; said he must go to the airfield at once. After a short pause the Lieutenant let them go.

According to eyewitness testimony and a subsequent investigation by the Gestapo, Stauffenberg's briefcase containing the bomb had been moved farther under the conference table in the last seconds before the explosion in order to provide additional room for the participants around the table. Consequently, the table acted as a partial shield, protecting Hitler from the full force of the blast, sparing him from serious injury of death. The stenographer Heinz Berger, died that afternoon, and three others, General Rudolf Schmundt, General Günther Korten, and Colonel Heinz Brandt did not recover from their wounds. Hitler's right arm was badly injured but he survived.

The original plan was for Ludwig Beck, Erwin von Witzleben and Erich Fromm to take control of the German Army. However, General Erich Fellgiebel, sent a message to General Friedrich Olbricht to say that Hitler had survived the blast. The most calamitous flaw in Operation Valkyrie was the failure to consider the possibility that Hitler might survive the bomb attack. Olbricht told Hans Gisevius, they decided it was best to wait and to do nothing, to behave "routinely" and to follow their everyday habits. Major Albrecht Metz von Quirnheim long closely involved in the plot, had already begun the action with a cabled message to regional military commanders, beginning with the words: "The Führer, Adolf Hitler, is dead."

Stauffenberg arrived back in Berlin and went straight to see General Friedrich Fromm. Stauffenberg insisted that Hitler was dead. Fromm replied that he had just learnt from Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel that Hitler had survived the bomb attack. Stauffenberg replied, "Field Marshal Keitel is lying as usual. I myself saw Hitler being carried out dead." He then admitted that he had planted the bomb himself. Fromm became very angry and declared that all the conspirators were under arrest, whereupon Stauffenberg retorted that, on the contrary, they were in control and he was under arrest.

Shortly after the assassination attempt, Joseph Goebbels broadcast a communiqué over German radio, assuring the public that Hitler was alive and well and that he would speak to the nation later that evening. Goebbels began the broadcast with the following words: Today an attempt was made on the Führer's life with explosives... The Führer himself suffered no injuries beyond light burns and bruises. He resumed his work immediately."

Albert Speer, minister of armaments, visited Goebbels soon after the broadcast. He described the scene outside: "The office windows looked out on the street. A few minutes after my arrival I saw fully equipped soldiers, in steel helmets, hand grenades at their belts and submachine guns in their hands, moving toward the Blandenburg Gate in small, battle ready groups. They set up machine guns at the gate and stopped all traffic. Meanwhile, two heavily armed men went up to the door along the park and stood guard there." However, Goebbels was not confident that he would not be arrested and carried with him some potassium cyanide capsules.

Goebbels was safe because the July 1944 Plot had been so badly organized. No real attempt had been made to arrest the Nazi leaders or to kill them. Nor did they secure immediate control of the radio and telephone communications systems. This was surprising as weeks earlier the original plan included the seizure of the long-distance telephone office, the main telegraph office, the radio broadcasting facilities in and around Berlin, and the central post office. "Incomprehensibly, the conspirators did not carry out these actions with sufficient dispatch, and this produced utter and fatal confusion."

Later that day, Goebbels told Heinrich Himmler: "If they hadn't been so clumsy! They had an enormous chance. What dolts! What childishness? When I think how I would have handled such a thing. Why didn't they occupy the radio station and spread the wildest lies? Here they put guards in front of my door. But they let me go right ahead and telephone the Führer, mobilize everything! They didn't even silence my telephone. To hold so many trumps and botch it - what beginners!"

Sometime between 8:00 and 9:00 p.m., the cordon that the conspirators had established around the government quarter was lifted. Military units that initially had supported the conspirators were switching loyalties back to the Nazis. The main reason for this was the series of radio announcements that were broadcast throughout Germany. By 10.00 p.m., forces loyal to the government were able to seize control of central headquarters and General Friedrich Fromm was released and Stauffenberg and his followers were taken prisoner.

Those arrested included Colonel-General Ludwig Beck, Colonel-General Erich Hoepner, General Friedrich Olbricht, Colonel Albrecht Metz von Quirnheim and Lieutenant Werner von Haeften. Fromm decided that he would hold an immediate court-martial. Claus von Stauffenberg spoke out, claiming in a few clipped sentences sole responsibility for everything and stating that the others had acted purely as soldiers and his subordinates.

All the conspirators were found guilty and sentenced to death. Hoepner, an old friend, was spared to stand further trial. Beck requested the right to commit suicide. According to the testimony of Hoepner, Beck was given back his own pistol and he shot himself in the temple, but only managed to give himself a slight head wound. "In a state of extreme stress, Beck asked for another gun, and an attendant staff officer offered him a Mauser. But the second shot also failed to kill him, and a sergeant then gave Beck the coup de grâce. He was given Beck's leather overcoat as a reward."

The condemned men were taken to the courtyard. Drivers of vehicles parked in the courtyard were instructed to position them so that their headlight would illuminate the scene. General Olbricht was shot first and then it was Stauffenberg's turn. He shouted "Long live holy Germany." The salvo rang out but Haeften had thrown himself in front of Stauffenberg and was shot first. Only the next salvo killed Stauffenberg and was shot first. Only the next salvo killed Stauffenberg. Quirnheim was the last man shot. It was 12.30 a.m.

On this day in 1938 surviving members of the International Brigades parade in Barcelona. On 21st September 1938, Juan Negrin announced at the United Nations the unconditional withdrawal of the International Brigades from Spain. At the time there were fewer than 10,000 foreigners left fighting for the Popular Front government. The International Brigades had suffered heavy casualties - 15 per cent killed and a total casualty rate of 40 per cent. At this time there were about 40,000 Italian troops in Spain. Benito Mussolini refused to follow Negrin's example and in reply promised to send Franco additional aircraft and artillery.

However, it took six weeks for the International Brigades to leave Spain. On 29th October 1938. Dolores Ibárruri, made a farewell speech. "Comrades of the International Brigades! Political reasons, reasons of state, the good of that same cause for which you offered your blood with limitless generosity, send some of you back to your countries and some to forced exile. You can go with pride. You are history. You are legend. You are the heroic example of the solidarity and the universality of democracy. We will not forget you; and, when the olive tree of peace puts forth its leaves, entwined with the laurels of the Spanish Republic's victory, come back! Come back to us and here you will find a homeland."

John Gates later wrote: "For the last time in full uniform, the International Brigades marched through the streets of Barcelona. Despite the danger of air raids, the entire city turned out. Whatever airforce belonged to the Loyalists, was used to protect Barcelona that day. Happily, the fascists did not show up. It was our day. We paraded ankle-deep in flowers. Women rushed into our lines to kiss us. Men shook our hands and embraced us. Children rode on our shoulders. The people of the city poured out their hearts. Our blood had been shed with theirs. Our dead slept with their dead. We had proved again that all men are brothers."

Bill Bailey, a former member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) who served in the Abraham Lincoln Battalion, did not leave until 15th November. He recalled: "Everyone who was able to walk was in the parade and the street was lined with people, throwing flowers, running out to hug and kiss us, tears in their eyes. It was sad to leave all these wonderful Spaniards at Franco's mercy. The last words spoken to us were that we should continue the anti-fascist struggle wherever we might be. And we did that to the best of our ability."

The International Brigades also suffered heavy losses during the Spanish Civil War. Approximately 4,900 soldiers died fighting for the Republicans (2,000 Germans, 1,000 French, 900 Americans, 500 British and 500 others).

On this day in 1943 Louisa Garrett Anderson died. Louisa was born on 28th July 1873. Her mother, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, had become the first woman to qualify as a doctor. Both her mother and her aunt, Millicent Garrett Fawcett, were leading figures in the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies.

Louisa was initially educated at home where one of her tutors was the feminist, Hertha Ayrton. Later she attended St Leonards School and Bedford College before entering the London School of Medicine for Women. She qualifying as a surgeon in 1897. Louisa was also active in the struggle for the vote and in 1903 she became chair-person of the Fulham branch of the NUWSS. However, she became very frustrated by the lack of progress in getting the vote and in 1907 she joined the Women Social & Political Union.

Evelyn Sharp spent time with Louisa and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson at their cottage in the Highlands: "Her daughter, who brought the same gifts of courage and perception, so rare in combination, to the service of the same cause, inherited all her mother's brains and culture, and more than her personal charm and gentleness. Her friendship was one of those I gained at that troublous time, and it offered generous compensation for many losses."

In October 1909 the Tax Resistance League was founded at a meeting at her flat in Harley Street. She also led the Medical Women Graduates section of the WSPU procession held on 21st June 1910. Anderson was arrested during a protest at the House of Commons in November but was released without charge.

In March 1912 the WSPU organised a new campaign that involved the large-scale smashing of shop-windows. May Billinghurst agreed to hide some of the stones underneath the rug covering her knees. According to Votes for Womennewspaper: "From in front, behind, from every side it came - a hammering, crashing, splintering sound unheard in the annals of shopping... At the windows excited crowds collected, shouting, gesticulating. At the centre of each crowd stood a woman, pale, calm and silent." Louisa Garrett Anderson was arrested during this demonstration and was sentenced to six weeks in Holloway Prison.

Millicent Garrett Fawcett was upset when she heard the news and wrote to her sister, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson: "I am in hopes she will take her punishment wisely, that the enforced solitude will help her to see more in focus than she always does." However, the authorities realised the dangers of her going on hunger strike and released her. In a speech she made on 18th April 1912 she announced she had been released because "the Home Office found that I might like to spend Easter with my family." She sent a letter to the British Medical Journal complaining about her preferential treatment.

Louisa Garrett Anderson was involved with Flora Murray and Catherine Pine in running the Notting Hill nursing home that WSPU members went to while recovering from hunger strikes. In 1912 she joined with Murray to establish the Women's Hospital for Children in the Harrow Road.

The summer of 1913 saw a further escalation of WSPU violence. In July attempts were made by suffragettes to burn down the houses of two members of the government who opposed women having the vote. These attempts failed but soon afterwards, a house being built for David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was badly damaged by suffragettes. This was followed by cricket pavilions, racecourse stands and golf clubhouses being set on fire.

Some leaders of the WSPU such as Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, disagreed with this arson campaign. When Pethick-Lawrence objected, she was expelled from the organisation. Others like Louisa Garrett Anderson and Elizabeth Robins showed their disapproval by ceasing to be active in the WSPU. Sylvia Pankhurst also made her final break with the WSPU and concentrated her efforts on helping the Labour Party build up its support in London.

On 4th August, 1914, England declared war on Germany. Two days later the NUWSS announced that it was suspending all political activity until the war was over. The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort.

During the First World War a group of wealthy suffragettes, including Janie Allan, decided to fund the Women's Hospital Corps. Louisa Garrett Anderson joined forces with Flora Murray to run a hospital in Claridge Hotel in Paris. Fellow WSPU member, Evelyn Sharp, who visited them in France, remarked: "It was in a way a triumph for the militant movement that these two doctors, who had been prominent members of the W.S.P.U., were the first to break down the prejudice of the British War Office against accepting the services of women surgeons." In February 1915 Anderson and Murray took charge of the Endell Street Military Hospital in London. Anderson was chief surgeon and the hospital treated 26,000 patients before it closed in 1919.

After the passing of the Qualification of Women Act the NUWSS and WSPU disbanded. A new organisation called the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship was established. As well as advocating the same voting rights as men, the organisation also campaigned for equal pay, fairer divorce laws and an end to the discrimination against women in the professions.

Anderson lost her early radicalism and joined the Conservative Party. In 1934 she became a justice of the peace and later became the mayor of Aldeburgh, Suffolk. She never married and was the constant companion of Flora Murray until her death from rectal carcinoma in 1923.

During the Second World War Anderson joined the surgical staff at the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital. In 1943 she was found to have disseminated malignant disease, and was taken to a nursing home in Brighton, where she died on 15th November 1943.