On this day on 22nd April

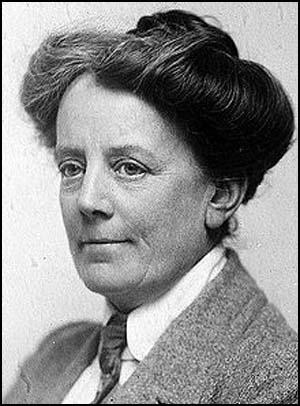

On this day in 1830 suffragist Emily Davies, the daughter of Reverend John Davies and Mary Hopkinson, was born in Gateshead. John Davies held traditional views on education and whereas Emily's three brothers were sent away to boarding school, she was taught at home. Emily was very close to her older brother, John Llewelyn. His success at Cambridge University made her realize how she had been denied an equal opportunity to an academic education.

In 1854 Emily met Elizabeth Garrett at the home of her friends, Jane and Emily Crow. Elizabeth introduced Emily to two other young feminists, Barbara Leigh Smith and Bessie Parkes.

Emily provided important support to Elizabeth Garrett who had embarked on her attempt to become a doctor. For a while Emily considered the possibility of studying medicine herself, but eventually she decided that her poor early education made this impossible. Emily Davies now made the decision that she would dedicate the rest of her life helping other young women obtain the opportunities that had been denied to her. This included a desire that women should be admitted to higher education and the professions on equal terms with men.

Emily's first campaign was to persuade the authorities to allow women to become students at London University. She also became involved in a campaign to secure the admission of girls to the Oxford and Cambridge examinations. In 1864 Emily had her first success when the Schools Enquiry Commission agreed to look into gender inequalities in education. To support her campaigns Emily wrote her book The Higher Education of Women.

In 1865 Emily joined with her friends Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, Barbara Bodichon, Dorothea Beale and Francis Mary Buss to form a woman's discussion group called the Kensington Society. The following year the group formed the London Suffrage Committee and began organizing a petition asking Parliament to grant women the vote.

Emily soon found herself in disagreement with most of the other members of the London Suffrage Committee. Members associated with the Radical Party, such as Barbara Bodichon and Helen Taylor, wanted votes for women on the same terms as men. Davies thought that they had more chance of success if they only asked for votes for unmarried women.

After this dispute, Emily Davies did not play a prominent role in the suffrage campaign for the next twenty years. Instead she concentrated on the idea of founding a women's college. With the help of Barbara Bodichon and other feminists, Emily raised enough money to purchase Benslow, a house two miles outside Cambridge. In 1873 Benslow House was opened as Girton College. However, women students at Girton were not admitted to full membership of the University of Cambridge until April 1948.

Emily's ideas on education were fairly conservative and this brought her into conflict with Barbara Bodichon. Emily believed that her students should concentrate on traditional subjects such as classics and mathematics whereas Bodichon favoured a more radical approach to the curriculum. The two women also disagreed on student discipline. Emily favoured a strict regime compared to Barbara's more liberal approach. Emily also insisted that the new college must be affiliated to the Church of England.

In 1889 Emily returned to the struggle for the vote when she joined the committee of the London National Society for Women's Suffrage. Emily played an active role in the National Union of Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) but was totally opposed to the militant tactics of the suffragettes.

Emily also had disagreements with the leadership of the NUWSS. Emily did not support the idea that all adults should have the vote and in 1912 she resigned when the organisation decided to give its full support to the Labour Party. Emily now joined the much smaller Conservative and Unionists Women's Franchise Society.

In 1919 Davies was one of the very few early members of the first Women's Suffrage Society still left alive to record their vote in a Parliamentary election. Emily Davies died in 1921.

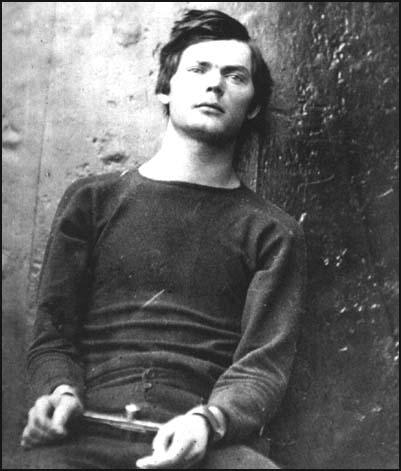

On this day in 1844, Lewis Powell, the son of a Baptist preacher, was born in Randolph County, Alabama, on 22nd April, 1844. The family moved to Florida in 1859 and Powell worked supervising his father's plantation until the outbreak of the American Civil War.

On 30th May, 1861, Powell joined the Second Florida Infantry. He was a member of the Confederate Army that fought at Gettysburg. He was wounded during the battle and taken prisoner. After being transferred to an hospital in Baltimore Powell escaped and enlisted in the Virginia Cavalry in the autumn of 1863. However, in January, 1865 he left the cavalry and took the Oath of Allegiance to the Union. At this time he began using the name Powell

Powell had a reputation for having a violent temper. While in a Branson boarding house he was reported to the military authorities for nearly killing an African American maid. A witness claimed that he "threw her on the ground and stamped on her body, struck her on the forehead, and said he would kill her".

Powell knew John Surratt who introduced him to John Wilkes Booth who recruited him to take part in his plot to kidnap Abraham Lincoln in Washington. The plan was to take Lincoln to Richmond and hold him until he could be exchanged for Confederate Army prisoners of war. Others involved in the plot included George Atzerodt, David Herold, Michael O'Laughlin and Samuel Arnold. Booth decided to carry out the deed on 17th March, 1865 when Lincoln was planning to attend a play at the Seventh Street Hospital that was situated on the outskirts of Washington. The kidnap attempt was abandoned when Lincoln decided at the last moment to cancel his visit.

On 9th April, 1865, General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox. Two days later Booth attended a public meeting in Washington where he heard Abraham Lincoln make a speech where he explained his views that voting rights should be granted to some African Americans. Booth was furious and decided to assassinate the president before he could carry out these plans.

Booth persuaded most of the people, including Powell, who had been involved in the kidnap plot to join him in his plan. Booth discovered that on 14th April, Abraham Lincoln was planning to attend the evening performance of Our American Cousin at the Ford Theatre in Washington. Booth decided he would assassinate Lincoln while George Atzerodt would kill Vice President Andrew Johnson and Powell agreed to murder William Seward, the Secretary of State. All attacks would take place at approximately 10.15 p.m. that night.

At 10.00 p.m. Powell and David Herold arrived at the home of William Seward, who was recovering from a serious carriage accident. When William Bell, a servant opened the door, Powell told him he had medicine from Dr. Tullio Verdi. When Bell refused to let him in, Powell pushed past him and rushed up the stairs. Frederick Seward, the Secretary of State's son, came out and asked him what he wanted. Powell hit Steward with his revolver so hard he fracturing his skull in two places. Powell was now confronted with George Robinson, Seward's bodyguard. Powell slashed him with his bowie knife before leaping onto Seward's bed and repeatedly stabbed him. Powell, thinking he had killed him, racing out of the house where Herold was waiting with his horse.

Herold went to Mary Surratt's boarding house and together with John Wilkes Booth, who had successfully killed Abraham Lincoln, headed for the Deep South. Whereas Powell hid for three days in a wood before visiting Sturratt's house. Unfortunately for Powell, soon afterwards the police arrived and arrested him and Mary Surratt.

On 1st May, 1865, President Andrew Johnson ordered the formation of a nine-man military commission to try the conspirators. It was argued by Edwin M. Stanton, the Secretary of War, that the men should be tried by a military court as Lincoln had been Commander in Chief of the army. Several members of the cabinet, including Gideon Welles (Secretary of the Navy), Edward Bates (Attorney General), Orville H. Browning (Secretary of the Interior), and Henry McCulloch (Secretary of the Treasury), disapproved, preferring a civil trial. However, James Speed, the Attorney General, agreed with Stanton and therefore the defendants did not enjoy the advantages of a jury trial.

The trial began on 10th May, 1865. The military commission included leading generals such as David Hunter, Lewis Wallace, Thomas Harris and Alvin Howe and Joseph Holt was the government's chief prosecutor. Powell, Mary Surratt, George Atzerodt, David Herold, Samuel Mudd, Michael O'Laughlin, Edman Spangler and Samuel Arnold were all charged with conspiring to murder Lincoln. During the trial Holt attempted to persuade the military commission that Jefferson Davis and the Confederate government had been involved in conspiracy.

Joseph Holt attempted to obscure the fact that there were two plots: the first to kidnap and the second to assassinate. It was important for the prosecution not to reveal the existence of a diary taken from the body of John Wilkes Booth. The diary made it clear that the assassination plan dated from 14th April. The defence surprisingly did not call for Booth's diary to be produced in court.

During his trial Powell was identified by all the people in Seward's house as the man who had attempted to kill the Secretary of State. Powell's lawyer, W. E. Doster, claimed in court that his client was insane. He argued that this had been caused by his experiences in the Confederate Army. Throughout the trial Powell insisted that Mary Surratt had not been part of the conspiracy.

On 29th June, 1865, Powell, Mary Surratt, George Atzerodt, David Herold, Samuel Mudd, Michael O'Laughlin, Edman Spangler and Samuel Arnold were found guilty of being involved in the conspiracy to murder Abraham Lincoln. Powell, Surratt, Atzerodt and Herold were hanged at Washington Penitentiary on 7th July, 1865.

On this day in 1858 Ethel Smyth, the fourth of the eight children of Major-General John Hall Smyth (1815–1894) and his wife, Emma Struth Smythe (1824–1891), was born at 5 Lower Seymour Street, London. In her autobiography she claimed that her father was very strict: "I think on the whole we were a naughty and very quarrelsome crew... Of course we merited and came in for a good deal of punishment, including having our ears boxed, which in those days was not considered dangerous... I think I am the only one of the six Miss Smyths who has ever been really thrashed; the crime was stealing some barley sugar, and though caught in the very act, persistently denying the theft. Thereupon my father beat me with one of grandmama's knitting needles, a thing about two and a half feet long with an ivory knob at one end.... Hit hard he did, for a fortnight later, when I joined Alice, who had been away all this time at an aunt's, she noticed strange marks on my person while bathing me, and was informed by me that it came from sitting on my crinoline... Even in after years my mother could not bear to think about that thrashing."

Ethel was much closer to her mother: "At this stage of my existence I stood in great awe of my father, but adored my mother, and remember her dazzling apparitions at our bedside when she would come to kiss us good-night before starting for an evening party. I often lay sleepless and weeping at the thought of her one day growing old and less beautiful. Besides this, wild passions for girls and women a great deal older than myself made up a large part of my emotional life, and it was my habit to increase the anguish of love by fancying its object was prey to some terrible disease that would shortly snatch her from me."

Emma Struth Smythe introduced her daughter to music: "She was in fact one of the most naturally musical people I have ever known; how deeply so I found out in after years when she came to Leipzig to see me, and I watched her listening for the first time to a Beethoven symphony - watched her face softening, tightening, relaxing again as each beauty I specially counted on went home. Old friends maintained that when she was young her singing would have melted a stone, which I can well believe all the warm, living qualities that made her so lovable must have got into it. When I knew her she had almost lost her voice, but enough remained to judge of its strangely moving timbre. Later on she loved to hear me sing, and it saddens me to think how seldom I gratified her when we were by ourselves; but I always was lazy about singing."

Her biographer, Elizabeth Kertesz, has pointed out: "She first became aware of her musical vocation in 1870, under the influence of a governess who had studied at the Leipzig conservatory. She was educated at home, with her five sisters, but was sent to school in Putney between 1872 and 1875. In spite of musical activities at school, she did not really begin to develop her talent until she returned to Frimley and received tuition from Alexander Ewing. This new friend and mentor encouraged her musical aspirations, while his wife, Juliana, foretold an author's career for their enthusiastic pupil. The fruitful contact was brought to an abrupt end by General Smyth's distrust of Ewing, but Smyth had already made up her mind to study composition in Leipzig."

However, Major-General John Hall Smyth refused permission for her to study music and insisted that she got married. According to Kertesz: "With her goal set, Smyth chafed at the social obligations of a marriageable young woman. She had tacit support from her mother, but quarrelled violently with her disapproving father and eventually resorted to militant tactics, locking herself in her room and refusing to attend social engagements. General Smyth finally agreed to her demand and she set off for Leipzig in July 1877. This was indeed a victory for a young woman of her class."

Smyth found Leipzig Conservatory disappointing and after a year she abandoned this institution to study privately with the composer Heinrich von Herzogenberg (1843–1900). Herzogenberg's wife, Lisl, became Smyth's first great love and the two women grew very close. Another biographer, Ronald Crichton, has commented: "On the whole it seems that the greatest and most enduring of her 'passions' were for older women with whom, through character or circumstance or both, physical gratification was out of the question even to one of her on-coming disposition."

Ethel Smyth claimed in her autobiography, Impressions that Remained (1919): "The moment has come to express regret that unlike other women writers of memoirs, such as Sophie Kowalewski, George Sand and Marie Bashkirtseff - if for a moment I may class myself with such as these - I have so far no orthodox love-affairs to relate, neither soulful sentiment for musician of genius, nor perilous passion conceived among the reeds of the Crostewitz lake for proud Prussian guardsman. In my letters to Lisl, where all the secrets of my heart stand revealed, I again and again express a conviction it is foolish to insist upon, so obvious is it, that the most perfect relation of all must be the love between man and woman, but this seemed to me, given my life and outlook, probably an unachievable thing."

In 1878 she went to live with the Herzogenberg family. Heinrich von Herzogenberg introduced Ethel to Johannes Brahms. She later recalled: "To my mingled delight and horror I learned, too, that Henschel had actually spoken to him about my work, telling him I had never studied, that he really ought to look at it and so on; and after the general rehearsal this good friend clutched and presented me all unawares. At that time Brahms was clean shaven, and in the whirl of emotion I only remember a strong alarming face, very penetrating bright blue eyes, and my own desire to sink through the floor when he said, as I then thought by way of a compliment, but as I now know in a spirit of scathing irony, So this is the young lady who writes sonatas and doesn't know counterpoint!"

In 1882 Ethel Smyth met Lisl Herzogenberg's sister Julia and her husband, Henry B. Brewster (1850–1908) in Florence. Brewster was an American writer and philosopher who had grown up in Europe. In her autobiography Impressions that Remained (1919) she pointed out: "It may be remembered that the Brewsters held unusual views concerning the bond between man and wife, views which up to the time of my arrival on the scene had not been put to the proof by the touch of reality. My second visit to Florence was fated to supply the test. Harry Brewster and I, two natures to all appearance diametrically opposed, had gradually come to realize that our roots were in the same soil - and this I think is the real meaning of the phrase to complete one another - that there was between us one of those links that are part of the Eternity which lies behind and before Time. A chance wind having fanned and revealed at the last moment, as so often happens, what had long been smouldering in either heart, unsuspected by the other, the situation had been frankly faced and discussed by all three of us; and I then learned, to my astonishment, that his feeling for me was of long standing, and that the present eventuality had not only been foreseen by Julia from the first, but frequently discussed between them. To sum up the position as baldly as possible, Julia, who believed the whole thing to be imaginary on both sides, maintained it was incumbent on us to establish, in the course of further intercourse, whether realities or illusions were in question. After that - and surely there was no hurry - the next step could be decided on. This view H. B. allowed was reasonable. My position, however, was that there could be no next step, inasmuch as it was my obvious duty to break off intercourse with him at once and for ever. And when I left Italy that chapter was closed as far as I was concerned." Her biographer, Elizabeth Kertesz, has argued: "She returned to Italy the following winter and found herself reciprocating Brewster's growing affection for her, although she tried to act honourably by breaking off all contact with him. Despite this renunciation, Lisl's loyalties were torn, and in 1885 she severed all contact with Smyth."

Ethel Smyth began to make a name for herself as a composer during this period. She wrote piano music and works for a variety of chamber ensembles in a style strongly influenced by the Brahmsian tradition. Most of these works were performed privately, but her string quintet (op. 1, 1883) and her violin sonata (op. 7, 1887) were played publicly at the Leipzig Gewandhaus. She returned to England, where no one knew of her German success. Ethel also had a great voice. Maurice Baring described her singing as "the rare and exquisite quality and deelicacy of her voice, the strange thrill and wail, the distinction and distinct, clear utterance".

In 1889 Ethel Smyth launched herself on the English musical scene with performances at the Crystal Palace of her Serenade in D and her Overture to Antony and Cleopatra . This was followed by the première of her Mass in D, performed by the Royal Choral Society and premiered at the Royal Albert Hallby the Royal Choral Society in 1893. These works established Smyth as the most important woman composer of her time. Claire Tomalin has argued: "Ethel's work did not stand in the way of her social activities, or her many passionate friendships. Throughout her life, she loved intensely, without regard to age or gender... She did defy - or perhaps rather ignore - all the stereotypes of her time, whether in matters of work, sex, class or even manners.... Over the next two decades she studied, composed and met most of the great figures of the day."

After Julia Brewster died in 1895 Ethel and Brewster were able to pursue their relationship more openly. Maurice Baring was a close friend: "His (Harry Brewster) appearance was striking; he had a fair beard and the eyes of a seer... someone said he looked like a Rembrandt. His manner was suave, and at first one thought him inscrutable - a person whom one could never know, surrounded as it were by a hedge of roses. When I got to know him better I found the whole secret of Brewster was this: he was absolutely himself; he said quite simply and calmly what he thought, and the truth is sometimes disconcerting when calmly expressed." According to Elizabeth Kertesz: "They neither married nor had children, and retained separate homes - she in England, he in Italy - but Brewster was a stable presence in Smyth's often stormy life.... his importance to her unaltered by her concurrent relationships with women." Ethel claimed that "Harry was never jealous of my women friends, in fact he held, as I do, that every new affection that comes into your life enriches older ties".

Smyth also wrote operas such as Der Wald (1901). Her work was difficult and her friend, Mabel Dodge, hired the His Majesty's Theatre for six performances of The Wreckers, a work that she had written with Henry B. Brewster. Smythe managed to persuade Thomas Beecham to conduct the work. Smyth had difficulty working with Beecham: "As the rehearsals wore on I discovered that in more respects than one my new friend was a disconcerting person to work with. For one thing he was never less than half an hour late, a habit which in that department of music life bears cruelly on all concerned. I also noticed that not only was it an effort to him to allow for the limitations of the human voice, to give the singers time to enunciate and drive home their words, but that qua musical instrument he really disliked the genus singer, which seemed an unfortunate trait in an opera conductor. In short, my impression was that his real passion was concert rather than opera conducting."

In his autobiography, A Mingled Chime (1944), Beecham explained why the opera was rarely produced: "This fine piece (The Wreckers) has never had a convincing representation owing to the apparent impossibility of finding an Anglo-Saxon soprano who can interpret revealingly that splendid and original figure, the tragic heroine Thirza. Neither in this part nor that of Mark, the tenor, have I heard or seen more than a tithe of that intensity and spiritual exaltation without which these two characters must fail to make their mark."

Ethel Smyth was a passionate supporter of women's rights and was a close friend of the three sisters, Millicent Garrett Fawcett, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and Agnes Garrett. All the women were members of the National Union of Suffrage Societies. Ethel went to live with them at Firs Cottage, in the village of Rustington. As Ethel pointed out: "Agnes and Rhoda Garrett, who were among the first women in England to start business on their own account and by that time were well-known house decorators of the Morris school... Both women were a good deal older than I, how much I never knew - nor wished to know, for Rhoda and I agreed that age and income are relative things concerning which statistics are tiresome and misleading."

Ethel Smyth met Emmeline Pankhurst in the summer of 1910. Fran Abrams the author of Freedom's Cause (2003), has argued: "Ethel Smyth, an endearingly eccentric bisexual composer who cheerfully confessed to having little or no political background and to caring even less about votes for women - until she met and fell passionately in love with the founder of the WSPU. At first glance Ethel Smyth made a curious companion for a political leader who, despite the violence which attached itself to her movement, remained resolutely feminine. While Emmeline usually had some lace about her person Ethel always dressed in tweeds, deerstalker and tie. Emmeline tended to attack every venture with passion while her new friend regarded the world with a wry, amused cynicism. Ethel, unlike Emmeline, had few sexual or personal inhibitions. But the two women, who at fifty-two were exactly the same age, immediately formed so close an attachment that Ethel decided to give two years of her life to the cause."

Smyth joined the Women's Social and Political Union and the following year she composed the WSPU battle song, The March of the Women . In 1912 the WSPU organised a new campaign that involved the large-scale smashing of shop-windows. Smythe took part in these activities and was with Emmeline Pankhurst when they were arrested: "The Downing Street window selected by Mrs Pankhurst was duly bombarded - I think she had two shots at it before they arrested her - but the stones never got anywhere near the objective. I broke my window successfully and was bailed out of Vine Street at midnight by wonderful Mr Pethick-Lawrence, who was ever ready to take root in any police station, his money bag between his feet, at any hour of the day or night."

Ethel Smyth was sentenced to two months in Holloway Prison. In her autobiography, Female Pipings for Eden (1933) she wrote: "The ensuing two months in Holloway, though one never got accustomed to an unpleasant sensation when the iron door was slammed and the key turned, were as nothing to me because Mrs Pankhurst was in with us. The merciful matron put us in adjoining cells, and at exercise, in chapel and on such other occasions as a kind-hearted matron can make for a prisoner, we saw more of each other than the protocol permitted. For instance she would often leave us together in Mrs Pankhurst's cell at tea-time 'just for a moment', lock us in, and forget to come back and conduct me to my own. But, as with policemen and detectives, Mrs Pankhurst refused to be softened by these favours, or by obviously sincere protestations of the 'it-hurts-me-more-than-it-hurts-you' order. And when, with an accent of cold scorn, she said, 'I would throw up any job rather than treat women as you say it is your didy to treat us,' the worst of it was that everyone knew this was nothing but the truth. According to Fran Abrams: "Ethel helped to organise athletic sports in the prison yard, which was even decorated by the women in the suffragette colours. As the women marched around the exercise yard singing March of the Women, an anthem she had composed for them, Ethel looked on from the window of her cell, marking time with a toothbrush."

On 4th August, 1914, England declared war on Germany. Two days later the NUWSS announced that it was suspending all political activity until the war was over. The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort.

Ethel Smyth has pointed out in her autobiography, Female Pipings for Eden (1933): "Mrs Pankhurst declared that it was now a question of Votes for Women, but of having any country left to vote in. The Suffrage ship was put out of commission for the duration of the war, and the militants began to tackle the common task."

It has been argued by Rebecca Jennings, the author of A Lesbian History of Britain (2007), that Smythe was a lesbian and that she was probably the lover of Emmeline Pankhurst, Edith Craig and Christabel Marshall. She also became involved with Virginia Woolf, who wrote in her diary: "An old woman of seventy-one has fallen in love with me... It is like being caught by a giant crab."

In 1922 Smyth was reated a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire. She also wrote two volumes of autobiography, Female Pipings for Eden (1933) and What Happened Next (1940).

Ethel Smyth died on 8th May 1944.

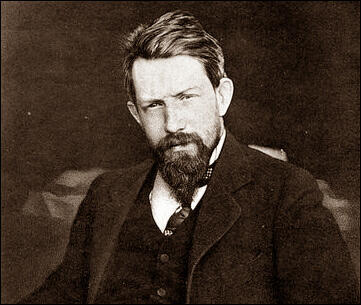

On this day in 1870 Vladimir Illich Ulyanov (later known as Lenin) was born in Simbirsk, Russia. His father, Ilya Ulyanov, a former science teacher, had recently become a local schools inspector. He held conservative views and was a devout member of the Russian Orthodox Church. Lenin had two older siblings, Anna (born 1864) and Alexander (born 1868). They were followed by three more children, Olga (born 1871), Dmitry (born 1874), and Maria (born 1878).

His mother, Maria Blank Ulyanov, had a German grandmother, and according to Maria Ulyanov. the children were "reared to a certain degree in German traditions". Maria was largely self-educated and taught herself German, French and English. She helped Vladimir with his studies and taught him to read and gave him piano lessons. He later gave this up as he thought playing the piano was "an unbecoming occupation for boys".

In 1874 Ilya Ulyanov was promoted to the post of director of schools. "Upon his shoulders lay the responsibility for the training, assignment, and discipline of the teachers, and for the organization and curricula of the elementary schools. In a province as backward and poor as Simbirsk the job was likely to be of back-breaking proportions. It took not only career considerations but real devotion to education on the part of Ulyanov to exchange the more congenial post of the high school teacher... for the task of supervising elementary education in a bleak province of about one million inhabitants."

Lenin was educated at the Simbirsk Gymnasium. His headmaster was Fyodor Kerensky, the father of Alexander Kerensky. Although Lenin despised the conservative views of his teachers he still managed to do well in his examinations. While at school he developed a love for history and languages. His brother, Dmitry, later recalled the meticulous care that he put into his homework: "He never wrote them on the eve of the day when they were to be handed in, as most students did. On the contrary, on being assigned the subject, Vladimir Ilyich set to work immediately. On a quarter of a sheet of paper he would make an outline together with the introduction and conclusion. He would then take another sheet, fold it in half, and make a rough draft on the left side of the paper, in accordance with his outline. The right side or margin remained clear. Here he would enter additions, explanations, corrections, as well as source indications... Then, shortly before it was necessary to hand it in, he would take some new clean sheets of paper and write the composition... referring to his notes and sources in various books."

His father was a monarchist and was a supporter of Tsar Alexander II and his Emancipation Manifesto that proposed 17 legislative acts that would free the serfs in Russia. Alexander announced that personal serfdom would be abolished and all peasants would be able to buy land from their landlords. The State would advance the the money to the landlords and they would recover it from the peasants in 49 annual sums known as redemption payments. However, as his critics pointed out: "With a population of sixty-seven million, Russia had twenty-three million serfs belonging to 103,000 landlords. The arable land which the freed peasantry had to rent or buy was valued at about double its real value (342 million roubles instead of 180 million); yesterday's serfs discovered that, in becoming free, they were now hopelessly in debt."

It is claimed that Ilya Ulyanov "believed in change, redemption, improvement, enlightenment, good deeds, cold baths, fresh air, and self-discipline" When the Tsar was assassinated in April 1881, he was extremely upset and left his office immediately, came home, put on his uniform and went to the cathedral, where a memorial service was conducted. "His children remarked on how shaken he was by the tragic event."

Ilya Ulyanov died of a brain haemorrhage in January 1886, when Lenin was 16. Soon afterwards he lost his faith. A friend later wrote: "When he perceived clearly that there was no God, he tore the cross violently from his neck, spat upon it contemptuously, and threw it away. In short he freed himself from religious prejudices in typical revolutionary Leninist fashion, without prolonged hesitation or timid consideration, without mental struggle with the spirit of doubt."

Lenin's brother, Alexander Ulyanov studied natural sciences at St. Petersburg University. He was an excellent student and at first he took no interest in politics and told a fellow student in 1886: "It is absurd, even immoral, for a man who has no understanding of medicine to cure the sick. How much more absurd and immoral it is to seek to heal social ills without understanding their cause."

Lenin idolized his older brother but was dismissive of his lack of interest in politics: "Alexander will never be a revolutionist. On his last summer visit home he spent his time preparing a dissertation on Annelides and worked constantly with his microscope. A revolutionist cannot possibly devote so much time to the study of Annelides." Ulyanov's studies won him a gold medal in zoology. However, after the death of his father, he became involved in politics.

Alexander Ulyanov became a member of the People's Will (Narodnaya Volya) and organization that had assassinated Alexander II and now had plans to kill his son, Alexander III. In secret meetings at his apartment, plans were laid to kill the Tsar on 1st March 1887, the sixth anniversary of the assassination of his father. Ulyanov also prepared a manifesto to the Russian people, to be published immediately after the Tsar's death. It began: "The spirit of the Russian land lives and the truth is not extinguished in the hearts of her sons."

As David Shub, the author of Lenin (1948), has pointed out, the secret police was aware of the conspiracy. "The date was advanced several days when the terrorists learned that the Tsar was planning to leave for his summer palace in the Crimea. Assassins were planted in the square before St Isaac's Cathedral. But the Tsar did not appear and at twilight the conspirators returned to their underground headquarters. Ulyanov then heard that on 28 February the Tsar was to drive along the Nevsky Prospect, probably to attend memorial services at his father's crypt in the Cathedral of St Peter and St Paul. Once more the terrorists waited, but no Tsar's carriage appeared. The secret police, suspecting an assassination plot, had warned the monarch to remain in the Winter Palace. Hours later the terrorists left their stations along the Nevsky and met in a tavern. One of them, Andreiushkin, had been shadowed for days by detectives. They followed him to the tavern, where he and his comrades were seized."

In Ulyanov's possession they found a code-book with a number of incriminating names and addresses, including that of the Polish revolutionary leader, Josef Pilsudski. Over the next few days hundreds of suspects were picked up in various cities and towns throughout Russia, the police having obtained the key to the code by torturing one of the terrorists. They singled out fifteen men, including Ulyanov, for trial. The charge: conspiracy to assassinate the Tsar.

Alexander's mother, Maria Ulyanov, wrote a letter to Tsar Alexander III and asked for permission to see her son. The Tsar wrote in the margin of the letter: "I think it would be advisable to allow her to visit her son, so that she might see for herself the kind of person this precious son of hers is." During her visit Ulyanov told his mother that he was sorry for the suffering he had caused her but admitted that his first allegiance was to the revolutionary movement. As a revolutionist, he had no alternative but to fight for his country's liberation.

At his trial Alexander Ulyanov refused to be represented by counsel and carried out his own defence. In an attempt to save his own comrades, he confessed to acts he had never committed. In his final address to the court Ulyanov argued: "My purpose was to aid in the liberation of the unhappy Russian people. Under a system which permits no freedom of expression and crushes every attempt to work for their welfare and enlightenment by legal means, the only instrument that remains is terror. We cannot fight this regime in open battle, because it is too firmly entrenched and commands enormous powers of repression. Therefore, any individual sensitive to injustice must resort to terror. Terror is our answer to the violence of the state. It is the only way to force a despotic regime to grant political freedom to the people." He stated that he was not afraid to die as "there is no death more honourable than death for the common good".

Ulyanov's mother pleaded with her son to ask for imperial clemency. He refused, although some of his co-defendants petitioned the Tsar and their death sentences were commuted. Helen Rappaport, the author of Conspirator: Lenin in Exile (2009): "On 8 May, having been lulled into a false sense of security that their sentences were to be commuted, the men were woken at 3.30 a.m. and informed that they were to be executed in half an hour's time. The prison officials had been so secretive in the construction of the gallows during those intervening three days that none of the prisoners in the isolation block had known. But they only had room for three gallows, which had been made up in sections, outside the prison, and silently assembled near the main entrance, without so much as a single blow of an axe being heard. As the rest of the prisoners slept the heavy sleep of those with an eternity on their hands, the commandant, priest and guards accompanied the five prisoners in single file to the place of execution. The condemned men were offered the consolation of a priest but all refused. There being only three gallows, they had to hang them in two batches... The sack was thrown over their heads and the stools kicked from under them. The condemned in Russia were not yet accorded the merciful death of the trapdoor, but a slower one, by strangulation."

When the St Petersburg newspaper carrying the news of Ulyanov's execution reached his family in Simbirsk. His 17 year-old brother, Lenin, was reported as saying "I'll make them pay for this! I swear it." However, he was not tempted to become a terrorist like his brother. According to his sister Maria, Lenin said: "No , we shall not take take that road (the one chosen by Alexander) our road must be different." Lenin was later to write: "The utter uselessness of terror is clearly shown by the experience of the Russian revolutionary movement... Individual acts of terrorism create only a short-lived sensation, and lead in the long run to an apathy, and the passive awaiting of yet another sensation."

Joel Carmichael has pointed out, Lenin and other young intellectuals in Russia turned away from terrorism to the ideas of Karl Marx: "Perhaps the chief appeal that Marxism held for the Russian intelligentsia, even more so than for the intellectuals of other countries, was its combination of a powerful messianic yearning with an appearance of scientific methodology. It offered youthful enthusiasts the best of both worlds. Their ardent desire to change the world was fortified by sound, or seemingly sound, scientific reasons as to why this was not only possible, but was, even more seductively, inevitable. As far as Russia was concerned, Marxism may be summed up as the contention that Russian history is a part of world history and that, because of this, Russia must pass through capitalism in order to reach the future socialist society. It was not the peasantry, Marxists thought, that would be able to lead the march to socialism, but the industrial working class. Terrorism had to be abandoned as a tactic that was both futile and, in view of the objectively developing social forces, superfluous. The main task of the revolutionary leaders was to be the creation of a disciplined working-class party to conduct Russia into the promised land."

As the brother of a state criminal, attempts were made to stop Lenin from entering university. Eventually he was allowed to study law at Kazan University. While at university Lenin became involved in politics. After one protest demonstration he was arrested and taken to the local police station. One of the police officers asked: "Why are you rebelling, young man? After all, there is a wall in front of you." Lenin confidently replied: "The wall is tottering, you only have to push it for it to fall over."

Lenin was now expelled from Kazan University and so he went to St. Petersburg and studied as an external student. After passing his law exams in 1891, Lenin started practising law in Samara. He studied the works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels but complained that he could find "no one in Samara who was interested in Marxist theory although there was a small group of Narodniki (populists) and a fairly good, illegal library... but there was no one with whom he could carry on intelligent theoretical discussions."

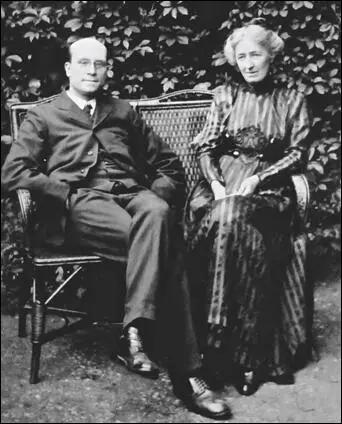

On this day in 1899 Alfred Salter writes letter to Ada Brown on love and politics."I have no lingering hankering after the fleshpots of Sudbury or Guy's or Harley Street, but I have sometimes hesitated a little - perhaps I ought to say quailed - before the dull, interminable, leisureless grind, the weary monotonous treadmill of work, that so certainly awaits me if I am to practise down here amongst the working people, and if I am to do so honourably and honestly and do my practice for other ends than money-getting... But it must be done, and the greatness of the task demands a proportionately great effort on my part. I think that the quality I admire most is fearlessness, and, in spite of haunting fears, I believe I have enough in my composition to dare to take up what I know is my divine vocation in a bold, confident, yes, and a defiant spirit. But I shall sorely need your help, your love, your support and your consolation. Without it life would be without flavour, future without hope, strife without encouragement. And yet it has been dawning on me recently that I have no right to ask you to share such risks, risks that may make you suffer. Anyhow, I have no business to go further without laying before you the fullest possible consequences of joining your life to mine and of throwing in your lot with me."

Alfred and Ada Salter decided to devote their lives to the people of Bermondsey and he established a general medical practice in the area. Salter rented out a shop on Jamaica Road and turned it into a surgery. They were married at Raunds on 22nd August 1900. Fenner Brockway has argued: "In Jamaica Road they began the partnership which was to bring something little short of a revolution to Bermondsey and its people."

Salter's takings during the first week amounted to 12s. 6d. As one source points out: "This did not last long, however; within a few weeks his problem became too many clients. It was not only his low charges which attracted patients: it was the treatment he gave and the way in which he gave it, it was the energy with which he insisted on beds in hospitals for urgent cases." Salter was so successful that he soon needed to recruit four other doctors to the surgery. They were chosen because they shared his basic values of Christian Socialism. Salter ran the surgery as a local cooperative and the five doctors shared their takings equally.

Ada and Alfred Salter were members of the Liberal Party but gradually grew disillusioned with its lack of radicalism and in May 1908 they joined the Independent Labour Party (ILP).This was partly because of the leadership of James Keir Hardie and his policies of "the school-feeding of hungry children, for old-age pensions, for the maintenance of the unemployed." They joined with twelve friends to establish a ILP branch in Bermondsey.

On this day in 1899 Lenin explains why he no longer considered Peter Struve a "comrade". Struve was born in Perm, Russia, in 1870. While studying at the University of St. Petersburg he was converted to Marxism. Over the next few years Struve wrote a series of articles on economics for radical journals published abroad.

In 1897 moved to Switzerland where he joined George Plekhanov, Pavel Axelrod, Vera Zasulich and Lev Deich and the rest of the Liberation of Labour Group living in exile. Struve helped the group to publish the newspaper, Rabochee Delo (Worker's Cause). Struve also became editor of the Marxist periodical, Novoe Slovo (New Word).

Struve was a foundation member of the Social Democratic Labour Party (SDLP) and in 1898 wrote the party's manifesto. He also wrote Critical Notes on the Economic Development of Russia and edited Nachalo (Beginning). However, Lenin considered that Struve had abandoned Marxism and no longer considered him a Marxist.

Following the abdication of Nicholas II Struve served as Minister of Foreign Affairs in the Provisional Government. An opponent of the October Revolution, Struve moved to France where he supported the White Army during the Civil War.

On this day in 1905 the Liberal Party takes control of East Grinstead council for the first time from the Conservative Party and Joseph Rice became chairman. The East Grinstead Observer reported: "The election of Joseph Rice as chairman of the East Grinstead Urban Council marks an entirely new departure on the part of that body. It is the first time a member of the trading community has been elected to that honourable position. By the choice made, the Council had recognised the claims of a class which really forms the very backbone of East Grinstead society and which is the chief contributor to the rates in the district. Many people entertain fears for the future. For my part, I have none."

On this day in 1910 Colonel Linley Blathwayt creates a suffragette arboretum in a field adjacent to the house. The idea was for women to be invited to plant a tree to commemorate their prison sentences and hunger strikes. On 23rd April 1909 Emily Blathwayt recorded in her diary that Annie Kenney, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Constance Lytton and Clara Codd all planted trees. "Beautiful day for the tree planting and Linley photographed the three in a group at each tree. Annie put the West one, Mrs. P. Lawrence, South, and Lady Constance the East. Miss Codd came to the field."

Over the next few months Emmeline Pankhurst, Adela Pankhurst, Mary Phillips, Vera Holme, Jessie Kenney, Georgina Brackenbury, Marie Brackenbury, Aeta Lamb, Theresa Garnett, Lilian Dove-Wilcox, Adela Pankhurst, Marion Wallace-Dunlop, Vera Wentworth and Elsie Howey also took part in this ceremony. After the visit of Christabel Pankhurst Emily Blathwayt wrote in her diary: "Christabel has planted her cedar of Lebanon by the pond; it was raining all the time. There is a wonderful charm about Christabel; she looks sweet and not like her photo. She is quiet and retiring." Eventually, even women who had not been to prison, such as Millicent Fawcett and Lilias Ashworth Hallett planted trees.

Jessie Kenney developed a "lung condition" also spent time recovering at Eagle House. Others who visited during this period included Constance Lytton, Elsie Howey, Mary Phillips, Charlotte Despard, Mary Allen, Charlotte Marsh, Lilias Ashworth Hallett, Aeta Lamb, Georgina Brackenbury, Marie Brackenbury, Marie Naylor, Laura Ainsworth, Lilian Dove-Wilcox, Theresa Garnett, Gladice Keevil, Maud Joachim, Vida Goldstein, Minnie Baldock, Vera Wentworth, Clare Mordan and Helen Watts. Colonel Blathwayt photographed the women. These were then signed and sold at WSPU bazaars.

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence wrote an article in Votes for Women in February 1909, they acknowledged the help given by the Blathwayt family to the cause of women's suffrage: "I say to you young women who have private means or whose parents are able and willing to support you while they give you freedom to choose your vocation. Come and give one year of your life to bringing the message of deliverance to thousands of your sisters... Put yourself through a short course of training under one of our chief officers or at headquarters in London, and then become one of our honorary staff organisers. Miss Annie Kenney, in the West of England, has two such honorary organisers. Miss Blathwayt is the only daughter of Colonel Lindley Blathwayt, of Bath. Yet her parents have set her free with their fullest approbation and sympathy, and with a generous allowance, to devote her whole time to the work."

On this day in 1915 Private W. Hay described a chlorine gas attack during the First World War. "We knew there was something was wrong. We started to march towards Ypres but we couldn't get past on the road with refugees coming down the road. We went along the railway line to Ypres and there were people, civilians and soldiers, lying along the roadside in a terrible state. We heard them say it was gas. We didn't know what the Hell gas was. When we got to Ypres we found a lot of Canadians lying there dead from gas the day before, poor devils, and it was quite a horrible sight for us young men. I was only twenty so it was quite traumatic and I've never forgotten nor ever will forget it."

After the first German chlorine gas attacks, Allied troops were supplied with masks of cotton pads that had been soaked in urine. It was found that the ammonia in the pad neutralized the chlorine. These pads were held over the face until the soldiers could escape from the poisonous fumes. Other soldiers preferred to use handkerchiefs, a sock, a flannel body-belt, dampened with a solution of bicarbonate of soda, and tied across the mouth and nose until the gas passed over. Soldiers found it difficult to fight like this and attempts were made to develop a better means of protecting men against gas attacks. By July 1915 soldiers were given efficient gas masks and anti-asphyxiation respirators.

One disadvantage for the side that launched chlorine gas attacks was that it made the victim cough and therefore limited his intake of the poison. Both sides found that phosgene was more effective than chlorine. Only a small amount was needed to make it impossible for the soldier to keep fighting. It also killed its victim within 48 hours of the attack. Advancing armies also used a mixture of chlorine and phosgene called 'white star'.

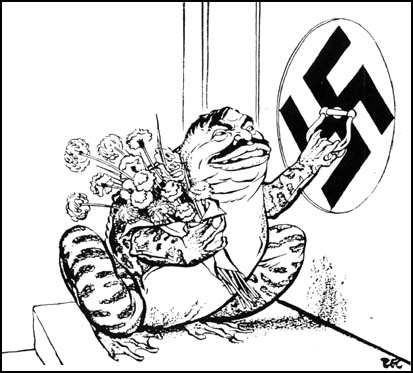

On this day in 1938 Margot Asquith, the wife of the former Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, accuses cartoonist David Low of encouraging hostility to Nazi Germany. "I thought your cartoon on Wednesday (20th April, 1938) in the Evening Standard both cruel and mischievous. I know the P.M. - do you? He is a man of iron courage, calm and resolution. Neville is doing the only right, wise, thing, unless you want war. Hate, threats - which you can't carry out - and suspicion do not advance peace, and if the P.M. fails we can always go back to the policy of the war-mongers - Winston Churchill and Co. I think Neville has saved the world by his courage - and so do much cleverer people than I."

On this day in 1942 French politician Pierre Laval explains why he supported Adolf Hitler. "In the event of a victory over Germany by Soviet Russia and England, Bolshevism in Europe would inevitably follow. Under these circumstances I would prefer to see Germany win the war. I feel that an understanding could be reached (with Germany) which would result in a lasting peace with Europe and believe that a German victory is preferable to a British and Soviet victory."

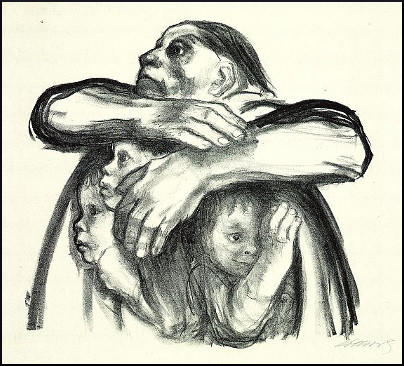

On this day in 1945 artist Käthe Kollwitz died.aged seventy-eight, at Moritzburg on 22nd April, 1945. Her biographer, Martha Kearns, commented: "She died without worldly possessions, but rich in her own person." In her time she had developed the strength "to take life as it is... to do one's work powerfully... not to deny oneself, the personality one happens to be, but to embody it."

Kollwitz had been a long-time critic of Adolf Hitler. In 1938 she finished the sculpture, Tower of Mothers. When this was shown at a local exhibition, it was seized by the Nazi government and described as being an example of "degenerate art". She wrote in her journal: "There is this curious silence surrounding the expulsion of my work from the Academy show.... Scarcely anyone had anything to say to me about it. I thought people would come, or at least write - but no. Such a silence around us."

In January, 1942, Kollwitz, aged 74, produced her last lithographic, Seed Crops should not be Milled. She wrote in her journal, "I have finished my lithograph... This time the seed for the planting - sixteen-year-old boys - are all around the mother, looking out from under her coat and wanting to break loose. But the old mother who is holding them together says, No! You stay here! For the time being you may play rough-and-tumble with one another. But when you are grown up you must get ready for life, not for war again."

Käthe Kollwitz, whose grandson, Peter, was named after her son killed in the First World War, joined the German Army. He was killed during the advance on Stalingrad in October, 1942. His father, Hans Kollwitz, recalled: "Even then she bore herself proudly, did not grieve openly, scarcely wept; she tried to give us strength to bear it. But the blow had been deep and damaging."

In 1943 Kollwitz produced her last self-portrait. Her biographer, Martha Kearns, has argued: "It is the last of eighty-four self-portraits, possibly the longest chronology of self-portraits by a woman in Western art, certainly a stunning psychological charting of a woman's life."

The terror-bombing of Berlin meant that in the summer of 1943, Kollwitz was forced to seek refuge in the home of a friend in Nordhausen. She was a prolific letter writer and in one letter to Georg Gretor, her adopted son, she wrote: "Oh, Georg, how good it all was... the fullness and richness of our lives overwhelms me again and again with feelings of gratitude. Let us tell you once more how we all have loved you."

On 23rd November, 1943, her apartment on 25 Weissenburger Strasse was destroyed by bombs and she lost family photographs, letters and mementos of her husband, sons and grandsons. She wrote: "It was my home for more than fifty years. Five persons whom I have loved so dearly have gone away from those rooms forever. Memories filled all the rooms... Only an idea remains, and that is fixed in the heart."

A week later her son's home was also destroyed during a bombing raid. Kollwitz wrote in her journal: "every war already carries within it the war which will answer it. Every war is answered by a new war, until everything, everything is smashed... That is why I am so wholeheartedly for a radical end to this madness, and why my only hope is in a world socialism... Pacifism simply is not a matter of calm looking on; it is work, hard work."