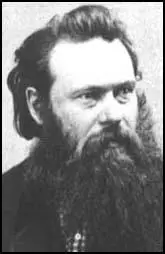

Alexander Gardner

Alexander Gardner was born in Paisley, Renfew, Scotland on 17th October, 1821. The family moved to Glasgow and at the age of fourteen Gardner left school and became an apprentice jeweler.

As a young man Gardner became interested in the socialist ideas being advocated by Robert Owen. Inspired by the New Harmony community established by Robert Dale Owen and Fanny Wright in Indiana, Gardner helped establish the Clydesdale Joint Stock Agricultural & Commercial Company. The plan was to raise funds and to acquire land in the United States.

In 1850 Gardner, his brother James Gardner, and seven others travelled to the United States. He purchased land and established a cooperative community close to Monona, in Clayton County, Iowa. Gardner returned to Scotland to help raise more money and to recruit new members.

Gardner used some of his funds to purchase the newspaper, the Glasgow Sentinel. Published every Saturday, the newspaper reported on national and international news. In his editorials, Gardner advocated social reforms that would benefit the working class. Within three months of taking control of the newspaper, circulation had grown to 6,500, making it the second-best selling newspaper in Glasgow.

In May, 1851, Gardner visited the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park, where he saw the photographs of Matthew Brady. Soon afterwards Gardner, who had always been interested in chemistry and science, began experimenting with photography. He also began reviewing exhibitions of photographs in the Glasgow Sentinel.

Gardner decided to emigrate to the United States in the spring of 1856. He took with him his mother, his wife, Margaret Gardner, and their two children. When he arrived at the Clydesdale colony, he discovered that several members were suffering from tuberculosis. His sister, Jessie Sinclair, had died from the disease and her husband was to follow soon afterwards.

Gardner decided to abandon the Clydesdale community and settle his family in New York. Soon afterwards he found employment as a photographer with Matthew Brady. Gardner was an expert in the new collodion (wet-plate process) that was rapidly displacing the daguerreotype. Gardner specialized in making what became known as Imperial photographs. These large prints (17 by 20 inches) were very popular and Brady was able to sell them for between $50 and $750, depending on the amount of retouching with india ink that was required.

In the 1850s Brady's eyesight began to deteriorate and began to rely heavily on Gardner to run the business. In February, 1858, Gardner was put in charge of Brady's gallery in Washington. He quickly developed a reputation as an outstanding portrait photographer. He also trained the young apprentice photographer, Timothy O'Sullivan.

On the outbreak of the American Civil War there was a dramatic increase in the demand for Gardner's work as soldiers wanted to be photographed in uniform before going to the front-line. The following officers were all photographed at the Matthew Brady Studio: Nathaniel Banks, Don Carlos Buell, Ambrose Burnside, Benjamin Butler, George Custer, David Farragut, John Gibbon, Winfield Hancock, Samuel Heintzelman, Joseph Hooker, Oliver Howard, David Hunter,John Logan, Irvin McDowell, George McClellan, James McPherson, George Meade, David Porter, William Rosecrans, John Schofield, William Sherman, Daniel Sickles, George Stoneman, Edwin Sumner, George Thomas, Emory Upton, James Wadsworth and Lew Wallace.

In July, 1861 Matthew Brady and Alfred Waud, an artist working for Harper's Weekly, travelled to the front-line and witnessed Bull Run, the first major battle of the war. The battle was a disaster for the Union Army and Brady came close to being captured by the enemy.

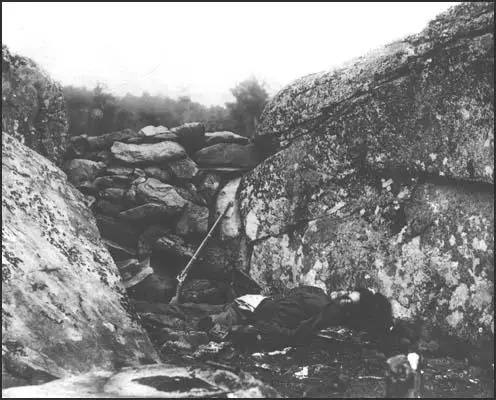

Soon after arriving back from the front Matthew Brady decided to make a photographic record of the American Civil War. He sent Gardner, James Gardner, Timothy O'Sullivan, William Pywell, George Barnard, and eighteen other men to travel throughout the country taking photographs of the war. Each one had his own travelling darkroom so that that collodion plates could be processed on the spot. This included Gardner's famous President Lincoln on the Battlefield of Antietam and Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter (1863).

In November, 1861, Gardner was appointed to the staff of General George McClellan, the commander of the Army of the Potomac. Granted the honorary rank of captain, Gardner photographed the battles of Antietam (September, 1862), Fredericksburg (December, 1862), Gettysburg (July, 1863) and the siege of Petersburg (June, 1864-April, 1865).

He also photographed Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, David Herold, Michael O'Laughlin, Edman Spangler and Samuel Arnold after they were arrested and charged with conspiring to assassinate Abraham Lincoln. He also took photographs of the execution of Surratt, Powell, Atzerodt and Herold were hanged at Washington Penitentiary on 7th July, 1865. Four months later he photographed the execution of Henry Wirz, the commandant of Andersonville Prison in Georgia.

After the war Brady established Gardner own gallery in Washington. This included taking photographs of convicted criminals for the Washington police force. He also published a two-volume collection of 100 photographs from the American Civil War, Gardner's Photographic Sketchbook of the War (1866).

In 1867 Gardner became the official photographer of the Union Pacific Railroad. As well as documenting the building of the railroad in Kansas, Gardner also photographed Native Americans living in the area. Alexander Gardner died in Washington in 1882.

Primary Sources

(1) Plans for the Clydesdale Joint Stock Agricultural & Commercial Company written by Alexander Gardner in 1848.

For the purpose of acquiring land in some suitable locality in the United States of America in which to establish by means of the united capital and industry of its partners a comfortable home for themselves and families where they may follow a more simple useful and rational mode of life than is found practicable in the complex and competitive state of society from which they have become anxious to retire.

(2) Alexander Gardner, editorial in the Glasgow Sentinel (April, 1852)

The present proprietor who had long felt the necessity of an efficient and independent Democratic newspaper in Scotland was induced to become the purchaser April last not as mere speculation in the usual sense of the term but as a means of enlightening the public on the great political, educational, and social questions of the times and of guiding right the popular mind of this country on all matters of state policy whatever advice was necessary or important.

(3) Alexander Gardner, reviewing an exhibition of photographs taken by Roger Fenton during the Crimean War (8th December, 1855)

The portraits of the heroes who have done so much for the honour of the allies are most vividly portrayed. We can hardly commend any of the photographs more than another, but we would suggest to the visitor to pay particular attention to the one on the "Council of War" held on the night previous to the taking of Mamelon.

(4) The Dumbarton Herald (10th January, 1856)

It will be seen from an advertisement in another column that Mr. Gardner is practicing among us as a photographic artist and the portraits he has turned out of several well known townsmen entitle him to be considered among the foremost professors of this beautiful art.

(5) Advert in the Washington Daily National Intelligencer (26th January, 1858)

M. B. Brady respectfully announces that he has established a Gallery of Photographic Art in Washington. he is prepared to execute commissions for the Imperial Photograph, hitherto made only at his well-known establishment in New York. A variety of unique and rare photographic specimens are included in his collection, together with portraits of many of the most distinguished citizens of the United States.

(6) A review of the exhibition of the photographs of Peninsula Campaign called Scenes and Incidents appeared in the New York World in July, 1862.

Brady's Photographic Corps, heartily welcomed in each of our armies, has been a feature as distinct and omnipresent as the corps of balloon, telegraph, and signal operators. They have threaded the weary stadia of every march; have hung on the the skirts of every battle scene; have caught the compassion of the hospital, the romance of the bivouac, the pomp and panoply of the field review.

(7) The New York Times on the photographs taken by Andrew Gardner, Matthew Brady, James Gardner, George Barnard and Timothy O'Sullivan (21st July, 1862)

Brady's artists have accompanied the army on nearly all its marches, planting their sun batteries by the side of our Generals' more deathful ones, and taking towns, cities and forts with much less noise and vastly more expedition. The result is a series of pictures christened Incidents of War, and nearly as interesting as the war itself: for they constitute the history of it, and appeal directly to the great throbbing hearts of the north.

(8) After seeing the photographs taken by Alexander Gardner at of the battle at Antietam, the writer, Oliver Wendell Holmes recorded his views on the nature of war.

Let him who wishes to know what war is look at this series of illustrations. It is so nearly like visiting the battlefield to look over these views that all the emotions excited by the actual sight of the stained and sordid scene, stewed with rags and wrecks, come back to us, and we buried them in the recesses of our cabinet as we would have buried the mutilated remains of the dead they too vividly represented. The sight of these pictures is a commentary on civilization such as the savage might well triumph to show its missionaries.

(9) Andrew Gardner took the famous picture Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter on 5th July, 1863. Two years later he wrote an account of the photograph.

The space between two large rocks was walled up and the loop holed so that he could take deliberate aim at any one who showed himself on round top, he had been wounded on the head with part of a shell. As the canteen and surrounding indicates that he had lain sometime before he died. When passing over the field in November afterwards I took a friend to see the place and there the bones lay in the clothes he had been wearing. He had evidently never been buried.

(x) Captain Christian Rath, was placed in charge of the execution of Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, David Herold, Michael O'Laughlin, Edman Spangler and Samuel Arnold. He was later interviewed about his role in the event.

I was determined to get rope that would not break, for you know when a rope breaks at a hanging there is a time-worn maxim that the person intended to be hanged was innocent. The night before the execution I took the rope to my room and there made the nooses. I preserved the piece of rope intended for Mrs. Surratt for the last.

I had the graves for the four persons dug just beyond the scaffolding. I found some difficulty in having the work done, as the arsenal attaches were superstitious. I finally succeeded in getting soldiers to dig the holes but they were only three feet deep.

The hanging gave me a lot of trouble. I had read somewhere that when a person was hanged his tongue would protrude from his mouth. I did not want to see four tongues sticking out before me, so I went to the storehouse, got a new white shelter tent and made four hoods out of it. I tore strips of the tent to bind the legs of the victims.

(x) William Coxshall, a member of the Veteran Reserve Corps, was assigned the task of dropping the trapdoor on the left side of the gallows.

The prison door opened and the condemned came in. Mrs. Surratt was first, near fainting after a look at the gallows. She would have fallen had they not supported her. Herold was next. The young man was frightened to death. He trembled and shook and seemed on the verge of fainting. Atzerodt shuffled along in carpet slippers, a long white nightcap on his head. Under different circumstances, he would have been ridiculous.

With the exception of Powell, all were on the verge of collapse. They had to pass the open graves to reach the gallows steps and could gaze down into the shallow holes and even touch the crude pine boxes that were to receive them. Powell was as stolid as if he were a spectator instead of a principal. Herold wore a black hat until he reached the gallows. Powell was bareheaded, but he reached out and took a straw hat off the head of an officer. He wore it until they put the black bag on him. The condemned were led to the chairs and Captain Rath seated them. Mrs. Surratt and Powell were on our drop, Herold and Atzerodt on the other.

Umbrellas were raised above the woman and Hartranft, who read the warrants and findings. Then the clergy took over talking what seemed to me interminably. The strain was getting worse. I became nauseated, what with the heat and the waiting, and taking hold of the supporting post, I hung on and vomited. I felt a little better after that, but not too good.

Powell stood forward at the very front of the droop. Mrs. Surratt was barely past the break, as were the other two. Rath came down the steps and gave the signal. Mrs. Surratt shot down and I believed died instantly. Powell was a strong brute and died hard. It was enough to see these two without looking at the others, but they told us both died quickly.