Henry Wirz

Henry Wirz was born in Zurich, Switzerland in 1822. After graduating from the University of Zurich he obtained medical degrees from Paris and Berlin. Wirz emigrated to the United States in 1849 and established a medical practice in Kentucky. After marrying he moved to Louisiana.

On the outbreak of the American Civil War he joined the Confederate Army. A sergeant in the Louisiana Volunteers, Wirz was badly wounded at the battle at Fair Oaks (May, 1862) and lost the use of his right arm. Unable to continue in active service, Wirz became a clerk at Libby Prison in Richmond. His commanding officer, Brigadier General John Henry Winder, was impressed by Wirz and he was soon promoted to the rank of major.

Wirz spoke fluent English, German and Dutch, and on the advice of General John Henry Winder, President Jefferson Davis decided to send him on a secret mission to England and France.

When Wirz returned to America he rejoined General John Henry Winder, who was now in charge of all Union Army prisoners east of the Mississippi. During the summer of 1863 an agreement under which Union and Confederate captives were exchanged, came to an end. There was now a rapid increase in the number of prisoners and so it was decided to build Andersonville Prison in Georgia. In April, 1864 Winder appointed Wirz as commandant of this new prison camp.

By August, 1864, there were 32,000 Union Army prisoners in Andersonville. The Confederate authorities did not provide enough food for the prison and men began to die of starvation. The water became polluted and disease was a constant problem. Of the 49,485 prisoners who entered the camp, nearly 13,000 died from disease and malnutrition.

When the Union Army arrived in Andersonville in May, 1865, photographs of the prisoners were taken and the following month they appeared in Harper's Weekly. The photographs caused considerable anger and calls were made for the people responsible to be punished for these crimes. It was eventually decided to charge General Robert Lee, James Seddon, the Secretary of War, and several other Confederate generals and politicians with "conspiring to injure the health and destroy the lives of United States soldiers held as prisoners by the Confederate States".

In August, 1865 President Andrew Johnson ordered that the charges against the Confederate generals and politicians should be dropped. However, he did give his approval for Wirz to be charged with "wanton cruelty". Wirz appeared before a military commission headed by Major General Lew Wallace on 21st August, 1865. During the trial a letter from Wirz was presented that showed that he had complained to his superiors about the shortage of food being provided for the prisoners. However, former inmates at Andersonville testified that Wirz inspected the prison every day and often warned that if any man escaped he would "starve every damn Yankee for it." When Wirz fell ill during the trial Wallace forced to attend and was brought into court on a stretcher.

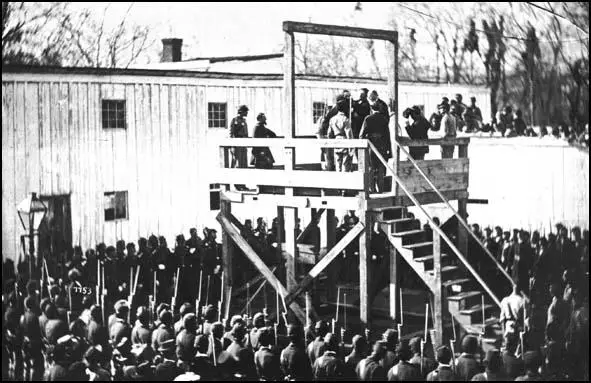

Wirz was found guilty on 6th November and sentenced to death. He was taken to Washington to be executed in the same yard where those involved in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln had died. Alexander Gardner, the famous photographer, was invited to record the event.

The execution took place on the 10th November. The gallows were surrounded by Union Army soldiers who throughout the procedure chanted "Wirz, remember, Andersonville." Accompanied by a Catholic priest, Wirz refused to make a last minute confession, claiming he was not guilty of committing any crime.

Major Russell read the death warrant and then told Wirz he "deplored this duty."Wirz replied that: "I know what orders are, Major. And I am being hanged for obeying them."

After a black hood was placed over his head, and the noose adjusted, a spring was touched and the trap door opened. However, the drop failed to break his neck and it took him two minutes to die. During this time the soldiers continued to chant: "Wirz, remember, Andersonville."

the death warrant to Henry Wirz on the gallows at Washington Penitentiary.

Primary Sources

(1) George Grey attempted to escape from Andersonville but was captured and punished by Henry Wirz. He gave evidence at Wirz's trial.

I was brought back to Andersonville prison and taken to Wirz's quarters. I was ordered by him to be put in the stocks, where I remained for four days, with my feet placed in a block and another lever placed over my legs, with my arms thrown back, and a chain running across my arms. I remained four days there in the sun; that was my punishment for trying to get away from the prison. At the same time a young man was placed in the stocks--the third man from me. He died there. He was a little sick when he went in, and he died there. I do not know his name; if I heard it, I have forgotten it. I am certain he died. The Negroes took him out of the stocks after he was dead, threw him into the wagon, and hauled him away.

Wirz shot a young fellow named William Stewart, a private belonging to the 9th Minnesota Infantry. He and I went out of the stockade with a dead body, and after laying the dead body in the dead-house Captain Wirz rode up to us and asked by what authority we were out there or what we were doing there. Stewart said we were there by proper authority. Wirz said no more, but drew a revolver and shot the man. After he was killed the guard took from the body about twenty or thirty dollars, and Wirz took the money from the guard and rode off, telling the guard to take me to prison.

(2) Edward Kellogg, of the 20th New York Regiment, arrived in Andersonville on 1st March, 1864. He gave evidence at Henry Wirz's trial.

I saw the cripple they called "Chickamauga" shot; he was shot at the south gate. He was in the habit of going off, I believe, to the outside of the gate to talk to officers and the guard, and he wanted to go off this day for something or other. I believe that he was afraid of some of our own men. He went inside the dead-line and asked to be let out. The refused to let him out, and he refused to go outside the dead-line. Captain Wirz came in on his horse and told the man to go outside the dead-line, and went off. After Captain Wirz rode out of the gate the man went inside the dead-line, and Captain Wirz ordered the guard to shoot him, and he shot him. The man lost his right leg, I believe, just above the knee. They called him "Chickamauga." I think he belonged to the Western army and was captured at Chickamauga. I think that was in May. I will not be certain as to the time.

I saw other men shot while I was there. I do not know their names. They were Federal prisoners. The first man I saw shot was shortly after the dead-line was established. I think it was in May. He was shot near the brook, on the east side of the stockade. At that time there was no railing; there was simply posts struck along where they were going to put the dead-line, and this man, in crossing, simply stepped inside one of the posts, and the sentry shot him. He failed to kill him, but wounded him. I don't know his name. I saw a man shot at the brook; he had just come in. He belonged to some regiment in Grant's army. I think this was about the first part of July or the latter part of June. He had just come in and knew nothing about the dead-line. There was no railing across the brook, and nothing to show that there was any such thing as a dead-line there. He came into the stockade, and after he had been shown his place where he was to sleep he went along to the brook to get some water. It was very dark, and a number of men were there, and he went above the rest so as to get better water. He went beyond the dead-line, and two men fired at him and both hit him. He was killed and fell right into the brook. I do not know the man's name. I saw other men shot. I do not know exactly how many. I saw several. It was a common occurrence.

(3) Augustus Moesner was a guard at Andersonville and gave evidence for Henry Wirz at his trial.

I never heard of Captain Wirz shooting, kicking, or beating a Federal prisoner while I was at Andersonville. I swear positively to that; I saw him pushing prisoners into the ranks, but not that they could be hurt. He would take them by the arm and push them into the ranks and say " God damn it! Couldn't you stay in the ranks where you were put?" He would not push them in violently - a gentle push. He was violent in these moments, cursing and swearing, as he always was with us, but he seemed harder than he was. I never saw him take any one by the throat, but by the shoulder or arm. Not with both hands; with one hand. I don't know which hand. I have seen him often go up the line of prisoners; I have seen him counting them, and I never saw him with his pistol in his hand on any of these occasions; it was his custom; he had his pistol in his belt. I saw him in the stockade while I was there; I saw him once at the south gate and once on horseback with Lieutenant Colonel Persons, and I saw him once in the stockade while I was outside. I saw him riding among the prisoners only once after I was taken out. On none of those occasions I never saw him carry a pistol except always in his belt. I swear positively that I never heard of Captain Wirz kicking or shooting a prisoner, nor in any way maltreating him except as I have .

When a man who had been ordered to wear a ball and chain complained that he was sick, a doctor was sent for, and if he found that it was so, the ball and chain would be taken off and the man would be sent to the hospital if necessary; also, when new squads of prisoners came in, and there were men among them who claimed to be sick, the doctor who was officer of the day was sent for, and he had to see if the men were really sick or not; the they were they were sent to the hospital. I recollect also that once there was a man amongst them who told me he was a hospital steward in our army; I spoke to Captain Wirz about it, and the man was immediately sent to the hospital as a steward; he was paroled and was not sent into the stockade at all. Some of the hospital attendants serenaded Captain Wirz and Dr. Stevenson, and I understood Dr. White too.

(4) Dr. John Bates was assistant surgeon at Andersonville and gave evidence for Henry Wirz at his trial.

The effect of scurvy upon the systems of the men as it developed itself there was the next thing to rottenness. Their limbs would become drawn up. It would manifest itself constitutionally. It would draw them up. They would go on crutches sideways, or crawl upon their hands and knees or on their haunches and feet as well as they could. Some could not eat unless it was something that needed no mastication. Sometimes they would be furnished beef tea or boiled rice, or such things as that would be given them, but not to the extent which I would like to see. In some cases they could not eat corn bread; their teeth would be loose and their gums all bleeding. I have known cases of that kind. I do not speak of it as a general thing. They would ask me to interest myself and get them something which they could swallow without subjecting them to so much pain in mastication. It seemed to me I did express my professional opinion that men died because they could not eat the rations they got.

I cannot state what proportion of the men in whose cases it became necessary to amputate from gangrenous wounds, and also to reamputate from the same cause, recovered. Never having charged my mind on the subject, and not expecting to be called upon in such a capacity, I cannot give an approximate opinion which I would deem reliable. In 1864, amputations from that cause occurred very frequently indeed; during the short time in 1865 that I was there, amputations were not frequent.

The prisoners in the stockade and the hospital were not very well protected from the rain; only by their own meager means, their blankets, holes in the earth, and such things. In the spring of 1865, when I was in the stockade, I saw a shed thirty feet wide and sixty feet long - the sick principally were in that. They were in about the same condition as those in the hospital. As to the prisoners generally, their only means of shelter from the sun and rain were their blankets, if they carried any along with them. I regarded that lack of shelter as a source of disease.

Rice, peas, and potatoes were the common issue from the Confederate government; but as to turnips, carrots, tomatoes, and cabbage, of that class of vegetables, I never saw any. There was no green corn issued. Western Georgia is generally considered a pretty good corn-growing country. Green corn could have been used as an anti-scorbutic and as and antidote. A vegetable diet, so far as it contains any alterative or medical qualities, serves as an anti-scorbutic.

The ration issued to the patients in the hospital was corn meal, beef, bacon - pork occasionally but not much of it; at times, green corn, peas, rice, salt, sugar, and potatoes. I enumerate those as the varieties served out. Potatoes were not a constant ration; at times they were sent in, perhaps a week or two weeks at a time, and then they would drop off. The daily rations was less from the time I went there in September, through October, November, and December, than it was from January till March 26th, the time I left. I never made a calculation as to the number of rations intended for each man; I was never called to do that. So far as I saw, I believe I would feel safe in saying that, while there might have been less, the amount was not over twenty ounces for twenty-four hours.

(5) A. G. Blair, who was captured at the battle of the Wilderness gave evidence at Henry Wirz's trial.

Captain Wirz planted a range of flags inside the stockade, and gave the order, just inside the gate, "that if a crowd of two hundred (that was the number) should gather in any one spot beyond those flags and near the gate, he would fire grape and canister into them. I think that the number of men shot during my imprisonment ranged from twenty-five to forty. I do not know that I can give any of their names. I did know them at the time, because they had tented right around me, or messed with me, but their names have slipped my mind. Two of them belonged to the 40th New York Regiment. Those two men were shot just after I got there, in the latter part of June, 1864.

I saw the sentry raise his gun. I shouted to the man. I and several of the rest gave the alarm, but it was to late. Both of these men did not die; one was shot through the arm; the other died; he was shot in the right breast. I did not see Captain Wirz present at the time. I did not hear any orders given to the sentinels, or any words from the sentinels when they fired; nothing more than they often said that it was done by orders from the commandant of the camp, and that they were to receive so many days furlough for every Yankee devil they killed. Those twenty-five or forty men were shot from the middle of June, 1864, until the 1st of September. There were men shot every month. I cannot say that I ever saw Captain Wirz present when any of these men were shot. The majority of those whom I saw shot were killed outright; expired in a few moments.