On this day on 18th July

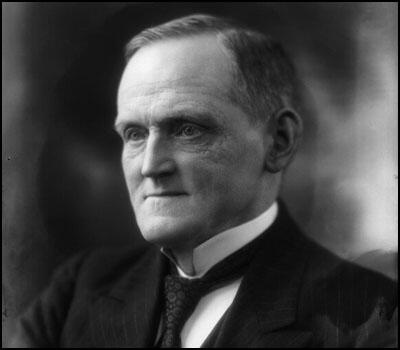

On this day in 1864 Philip Snowden, the son of a weaver, was born in the village of Cowling, in the West Riding of Yorkshire on 18th July, 1864. His parents were devout followers of the religious ideas of John Wesley and as a boy he was brought up as a strict Methodist. John Snowden was a member of the Temperance Society and Philip followed his father's example and never drank alcohol. Philip did well at school and at the age of fifteen was able to work as a clerk in an insurance office.

Snowden joined the Keightley Liberal Club and he agreed to present a paper on the dangers of socialism. While researching this paper Snowden became converted to this new ideology. Snowden left the Liberal Party and joined the local branch of the Independent Labour Party (ILP). Snowden soon developed a reputation as a fine orator and for the next few years he travelled the country making speeches for the ILP. He drew large crowds and only Keir Hardie was considered his equal as a platform speaker.

In 1899 Snowden was elected to the Keightley Town Council and the School Board. He also served as editor of a local socialist newspaper. Snowden continued to travel the country and in 1903 was elected as the national chairman of the Independent Labour Party. Like Keir Hardie, Snowden was a Christian Socialist, and in 1903 the two men wrote a pamphlet together on their beliefs, The Christ that is to Be.

In 1903 Snowden married Ethel Annakin, an active member of the NUWSS. Ethel converted her husband to the cause of votes for women. Over the next ten years, Snowden, who was a member of the Men's League For Women's Suffrage and gave considerable support to the campaign for equal rights.

Snowden made several attempts to enter the House of Commons. Snowden was defeated at Blackburn in the 1900 General Election. He also failed at the Wakefield by-election in 1902. Snowden was finally successful in the 1906 General Election when he was elected as the Labour MP for Blackburn.

During this period Snowden wrote a great deal about his views on Christian Socialism, the Temperance Movement and economics issues. This included The Socialist's Budget (1907), Old Age Pensions (1907), Socialism and the Drink Question (1908), Socialism and Teetotalism (1909) and the Living Wage (1909). In the House of Commons Snowden developed a reputation as an expert on economic issues and advised David Lloyd George on his 1909 People's Budget.

Philip Snowden was a pacifist and refused to support Britain's involvement in the First World War. Philip and Ethel Snowden both joined the Union of Democratic Control (UDC). Other members included Arthur Ponsonby, J. A. Hobson, Charles Buxton, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Norman Angell, Arnold Rowntree, Philip Morrel, Morgan Philips Price, George Cadbury, Helena Swanwick, Fred Jowett, Ramsay MacDonald, Tom Johnston, Arthur Henderson, David Kirkwood, William Anderson, Isabella Ford, H. H. Brailsford, Israel Zangwill, Bertrand Russell, Margaret Llewelyn Davies, Konni Zilliacus, Margaret Sackville, Olive Schreiner and Morgan Philips Price.

The Union of Democratic Control soon emerged at the most important of all the anti-war organizations in Britain and by 1915 had 300,000 members. Frederick Pethick-Lawrence explained the objectives of the UDC: "As its name implies, it was founded to insist that foreign policy should in future, equally with home policy, be subject to the popular will. The intention was that no commitments should be entered into without the peoples being fully informed and their approval obtained. By a natural transition, the objects of the Union came to include the formation of terms of a durable settlement, on the basis of which the war might be brought an an end."

When the First World War was declared two pacifists, Clifford Allen and Fenner Brockway, formed the No-Conscription Fellowship (NCF), an organisation that encouraged men to refuse war service. The NCF required its members to "refuse from conscientious motives to bear arms because they consider human life to be sacred." As Martin Ceadel, the author of Pacifism in Britain 1914-1945 (1980) pointed out: "Though limiting itself to campaigning against conscription, the N.C.F.'s basis was explicitly pacifist rather than merely voluntarist.... In particular, it proved an efficient information and welfare service for all objectors; although its unresolved internal division over whether its function was to ensure respect for the pacifist conscience or to combat conscription by any means"

Snowden also gave his support to the No-Conscription Fellowship. Other members of the group included Bertrand Russell, Bruce Glasier, Robert Smillie, C. H. Norman, William Mellor, Arthur Ponsonby, Guy Aldred, Alfred Salter, Duncan Grant, Wilfred Wellock, Maude Royden, Max Plowman, John Clifford, Cyril Joad, Alfred Mason, Winnie Mason, Alice Wheeldon, William Wheeldon, John S. Clarke, Arthur McManus, Hettie Wheeldon, Storm Jameson and Duncan Grant.

Like other anti-war Labour MPs, Snowden was defeated in the 1918 General Election. Snowden was eventually forgiven and was elected to represent Colne Valley in the 1922 General Election.

When Ramsay MacDonald formed the first Labour Government in January, 1924, he appointed Philip Snowden as his Chancellor of the Exchequer. Snowden reduced taxes on various commodities and popular entertainments, but was criticised by members of the Labour Party for not introducing any socialist measures. Snowden replied that this was not possible as the Labour government had to rely on the support of the Liberal Party to survive. When Stanley Baldwin, the leader of the Conservative Party, became Prime Minister later that year, Snowden's period in office came to an end.

Snowden returned as Chancellor of the Exchequer in the Labour Government of 1929. This coincided with an economic depression and Snowden's main concern was to produce a balanced budget. However, he did manage to make changes to the tax system that resulted in the wealthy paying more and the poor paying less. The economic situation continued to deteriorate and in 1931 Snowden suggested that the Labour government should introduce new measures including a reduction in unemployment pay. Several ministers, including George Lansbury, Arthur Henderson and Joseph Clynes, refused to accept the cuts in benefits and resigned from office.

Ramsay MacDonald now formed a National Government with Conservative and Liberal politicians. Snowden remained Chancellor and now introduced the measures that had been rejected by the previous Labour Cabinet. Labour MPs were furious with what MacDonald and Snowden had done, and both men were expelled from the Labour Party.

Snowden did not stand in the 1931 General Election and instead accepted the title that enabled him to sit in the House of Lords.

Philip Snowden died on 15th May, 1937.

On this day in 1872 the Secret Ballot Act is passed by Parliament. In his first speech as Prime Minister, William Gladstone told the audience that he intended to introduce legislation that would allow secret voting to take place. "I have at all times given my vote in favour of open voting, but I have done so before, and I do so now, with an important reservation, namely, that whether by open voting or by whatsoever means, free voting must be secured."

Michael Partridge, the author of Gladstone (2003) has argued that John Bright only accepted office in the cabinet as President of the Board of Trade, on the understanding that Gladstone would introduce a bill bringing in secret ballot for elections. In 1871 the Ballot Bill by William Forster. It was passed by the House of Commons on 8th August, only for it to be defeated in the House of Lords two days later.

Benjamin Disraeli, the leader of the Conservative Party, made it clear that he was totally opposed to the measure. He argued that the country had experienced too much parliamentary reform over the last few years and that it had encouraged public disorder: "This arrangement about the ballot is part of the, same system, a system which would dislocate all the machinery of the state, and disturb and agitate the public mind."

Gladstone was determined not to give up and the Secret Ballot bill was reintroduced in 1872. It was passed by the House of Commons and when it was sent to the House of Lords the peers were warned that the government would call a general election if they rejected it a second time. As a result the act was passed on 18th July 1872. The first secret-ballot by-election took place as early as 15th August.

Paul Foot points out that in the 1874 General Election, none of Disraeli's terrible prophecies came true and it was a much more fairer contest: "At once, the hooliganism, drunkenness and blatant bribery which had marred all previous elections vanished. employers' and landlords' influence was still brought to bear on elections, but politely, lawfully, beneath the surface."

On this day in 1890 Lydia Becker while visiting the health resort of Aix-les-Bains, she caught diphtheria and died.

Lydia Becker the daughter of Hannibal Becker, the owner of a chemical works in Manchester, and Mary Duncuft, was born on 24th February, 1827. The eldest of fifteen children, Lydia, like the rest of her sisters, was educated at home. After the death of her mother in 1855, Lydia had the responsibility of looking after her younger brothers and sisters.

Lydia developed an interest in botany and in 1864 won an award for her collection of dried plants and in 1866 her book Botany for Novices, was published. The following year Lydia founded the Manchester's Ladies Literacy Society, which despite its name was intended as a society to study scientific matters."

In 1866 Lydia heard Barbara Bodichon give a lecture on women's suffrage at a meeting in Manchester. She was immediately converted to the idea that women should have the vote and wrote an article Female Suffrage for the magazine, The Contemporary Review. Emily Davies and Elizabeth Wolstenholme were two of the women who read the article and later that year they joined with Lydia Becker to form the Manchester Women's Suffrage Committee. Wolstenholme then arranged to have 10,000 copies of the article printed as a pamphlet.

In the House of Commons the Radical MP, John Stuart Mill campaigned with Henry Fawcett and Peter Alfred Taylor for parliamentary reform and in 1866 presented the petition organised by Barbara Bodichon, Emily Davies, Elizabeth Garrett and Dorothea Beale in favour of women's suffrage. Mill, added an amendment to the 1867 Reform Act that would give women the same political rights as men. However, the amendment was defeated by 196 votes to 73.

During the debate on Mill's amendment, Edward Kent Karslake, the Conservative MP for Colchester, said in the House of Commons that the main reason he opposed the measure was that he had not met one woman in Essex who agreed with women's suffrage. Lydia Becker, Helen Taylor and Frances Power Cobbe, decided to take up this challenge and devised the idea of collecting signatures in Colchester for a petition that Karslake could then present to parliament. They found 129 women resident in the town willing to sign the petition and on 25th July, 1867, Karslake presented the list to parliament. Despite this petition the Mill amendment was defeated by 196 votes to 73.

In 1868 she became treasurer of the Married Women's Property Committee and also joined Josephine Butler in her campaign against the Contagious Diseases Acts. Becker continued to write articles about the need for parliamentary reform and in 1870 she established the Women's Suffrage Journal. Becker was also involved in other feminist campaigns.

The 1870 Education Act allowed women to vote and serve on School Boards. Lydia Becker was elected to the Manchester School Board where she took a strong interest in improving the education of girls in the city. Becker criticised the domestic education of girls in Manchester's schools and argued that boys should be taught to mend their own socks and cook their own meals.

In 1874 William Forsyth MP announced he was willing to promote a bill that would grant single, but not married women, the vote. Becker, who was unmarried, created a controversy in the suffrage movement when she supported this proposal. Although Becker only suggested this as a short-term strategy, some married suffragists, such as Emmeline Pankhurst, were outraged by her views. Later that year Becker was forced to resign from the Married Women's Property Committee.

In 1881 Lydia Becker received a letter from the Central Society for Women's Suffrage offering her the post of paid secretary of the organisation. She held the post for the next three years. Becker was elected as president of National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) in 1887.

Becker's biographer, Linda Walker, has argued: "As a public speaker she lacked oratorical flair, but was noted for persuasiveness and clarity of thought; she undertook onerous lecture tours at a time when it was thought unseemly for a lady to appear on a public platform. Physically stout from early womanhood, her broad, flat face, wire-rimmed spectacles, and plaited crown of hair were a cartoonist's delight, and she was much lampooned in the popular press. However, she quickly gained recognition as the movement's key strategist, directing national policy and tactics with a statesmanlike mind: the women-only great demonstrations held throughout the country in 1880 attracted capacity crowds and enormous publicity for the cause."

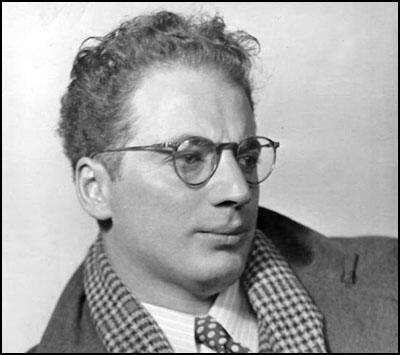

On this day in 1906 playwright Clifford Odets, the son of Jewish immigrants, was born in Philadelphia. He left school at the age of 17 to become an actor. After a series of small parts working in the theatre and on radio, Odets helped form the Group Theatre in New York City. Members held left-wing political views and wanted to produce plays that dealt with important social issues.

Odets, who joined the American Communist Party in 1934, had his first play produced, Waiting for Lefty, in 1935. The play that dealt with trade union corruption, was an immediate success. With his next two plays, Awake and Sing! and Till the Day I Die, Odets established himself as a champion of the underpriviledged.

After the production of Paradise Lost (1935), Odets accepted a lucrative offer to become a film screenwriter and while in Hollywood met and married the actress, Luise Rainer. However, he continued to write plays and with Golden Boy (1937) he had his greatest commercial success. This was followed by Rocket to the Moon (1938), Night Music (1940) and Clash By Night (1941).

A non-conformist actress, Rainer refused to accept the values of Hollywood. In 1937 Rainer had to be forced by Louis B. Mayer to receive her Oscar. She later claimed that: "For my second and third pictures I won Academy Awards. Nothing worse could have happened to me." The studio insisted on forcing her into roles she considered unworthy of her talents. “All kinds of nonsense... I didn’t want to do it, and I walked out." Mayer said, "That girl is a Frankenstein, she’s going to ruin our whole firm... we made you and we are going to destroy you". Rainer decided to leave Hollywood. The director, Dorothy Arzner, claims that she was being badly treated because she had married a communist.

Odets and Luise Rainer moved to New York City. They also spent time in Nichols, Connecticut. Rainer said that Odets was ''my passion’’ but was a possessive man. When Rainer developed a friendship with Albert Einstein, Odets was said to be so consumed with jealousy that he savaged a photograph of Einstein with a pair of scissors. The couple were divorced in 1943.

Odets also wrote The Big Knife (1949), and The Country Girl (1950). Investigated by Joseph McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1953, Odets argued that he had never been under the infuence of the American Communist Party and his work had been based on his deep sympathy for the working classes. Unlike many writers and actors who had been members of the party, Odets was not blacklisted and continued to work in Hollywood. This included the screenplay for the acclaimed, Sweet Smell of Success (1957).

Clifford Odets died on 18th August, 1963.

On this day in 1907 Victor Grayson is elected to Parliament. In January 1907, the Independent Labour Party in Colne Valley selected Victor Grayson as their parliamentary candidate to replace Tom Mann, who had decided to concentrate on trade union matters. In the past, there had been an arrangement where the labour movement supported the Liberal Party candidate in Colne Valley in return for help in winning other seats for ILP candidates. The executive of the Labour Party therefore decided not to endorse Grayson as their candidate. In choosing their candidate the people of Colne Valley "selected someone with little experience whom they trusted."

Keir Hardie was unhappy with the decision. He wrote to John Bruce Glasier that "I don't like the man they have chosen but that cannot be helped". Hardie later reported: "Mr Grayson's work in the movement, valuable as it had been, was a matter of very few years... There was neither anger nor bias against Mr Grayson, but simply a desire that men who had grown grey in the movement should not feel that they were put aside to make room for younger men."

Victor Grayson became a regular speaker in the town. Kenneth O. Morgan points out that Grayson was "a spell-binding orator, with a kind of film-star charisma, a supreme rebel propelled from nowhere to smash down the crumbling edifice of British capitalism". What was also surprising that he was able to do it in Colne Valley: "How could the solid, respectable, nonconformist cotton and woollen workers of Colne Valley, close to much older forms of industrial production, relatively well-housed and well-paid, and almost all in regular employment allow themselves to be so swept up in the millenarian intensity of Grayson's crusade in 1907?"

The Colne Valley Guardian was shocked by the appeal of Grayson's socialist campaign: "It is somewhat of a paradox but nevertheless true, that the measure of its discontent, and the higher the wages, the more eager is the straining after the chimerical ideals of Socialism. For the last seven or eight years the Colne Valley has enjoyed an unparalleled period of commercial prosperity. That has not been due entirely to the manufacturers, nor yet to the mill-workers but to both combined."

Harry Hoyle, who was only 12 years old at the time, remembers Grayson speaking in the town: "I can picture him now in front of the Co-op at the Market Place in Marsden. They had a wagon for a platform... He seemed so enthusiastic about everything he attempted, he gave you the impression that this is what we want and this is what we must have... it was infectious. It was really. People just went hay-wire. They went mad at his meetings."

Colne Valley ILP refused to back down and in the by-election held in July, 1907, Grayson stood as an Independent Socialist candidate. Only three leading figures in the ILP, Katherine Glasier, Philip Snowden and J. R. Clynes were willing to speak at his meetings during the campaign. As Reg Groves, the author of The Strange Case of Victor Grayson (1975), has pointed out: "The socialists had no money, save the pennies collected amongst their fellow workers in the mills and factories and at meetings. As the campaign grew, money was raised by more desperate measures; watches, household goods, even wedding rings were pawned to keep the supply of money flowing. They had no efficient, smooth working electoral machinery; it had to be improvised on the spot. The trade union machinery which might well have added much in the way of organisation and wide-flung influence was not likely to give its unstinted support, since the Labour Party refused its endorsement; the ILP, too, was antagonistic, and many of the local union officials favoured a policy of working with the Liberals, not against them."

Although the ILP was committed to the parliamentary road to socialism, during the election, Grayson advocated revolution. In his election address Grayson wrote: I am appealing to you as one of your own class. I want emancipation from the wage-slavery of Capitalism. I do not believe that we are divinely destined to be drudges. Through the centuries we have been the serfs of an arrogant aristocracy. We have toiled in the factories and workshops to grind profits with which to glut the greedy maw of the Capitalist class. Their children have been fed upon the fat of the land. Our children have been neglected and handicapped in the struggle for existence. We have served the classes and we have remained a mob. The time for our emancipation has come. We must break the rule of the rich and take our destinies into our own hands. Let charity begin with our children. Workers, who respect their wives, who love their children, and who long for a fuller life for all. A vote for the landowner or the capitalist is treachery to your class. To give your child a better chance than you have had, think carefully ere you make your cross. The other classes have had their day. It is our turn now."

At least forty clergymen worked on Grayson's behalf. His supporters sung Jerusalem, England Arise and The Red Flag at meetings and their main slogan was "Socialism - God's Gospel for Today". One of his most important campaigners was W. B. Graham, the giant curate of Thongsbridge. The left-wing journalist, Robert Blatchford, described him as "six foot a socialist and five inches a parson". Graham's mission was the "Christianizing of Christianity".

Victor Grayson also campaigned for votes for women. Hannah Mitchell joined his campaign and later recalled: "I must have worked the Colne Valley from end to end, often under the auspices of the Colne Valley Labour League. Sometimes we just went... from door to door to ask the women to come and listen (to Victor Grayson), which the Colne Valley women were usually willing to do." Emmeline Pankhurst also visited the town in support of Grayson. The Daily Mirror pointed out that "Colne Valley mill girls... many of them who cared nothing about votes before are now eager in their desire to enjoy the privileges of the franchise."

In one of his speeches Grayson outlined his view on women's suffrage: "The placing of women in the same category, constitutionally, as infants, idiots and Peers, does not impress me as either manly or just. While thousands of women are compelled to slave in factories, etc., in order to earn a living; and others are ruined in body and soul by unjust economic laws created and sustained by men, I deem it the meanest tyranny to withhold from women the right to share in making the laws they have to obey. Should I be honoured with your support, I am prepared to give the most immediate and enthusiastic support to a measure giving women the vote on the same terms as men. This is as a step to the larger measure of complete Adult Suffrage."

The election took place on 18th July, 1907. Almost every eligible registered elector cast his vote and a turn-out of eighty-eight per cent was recorded. Grayson received 3,648 votes and this gave him a majority over his two opponents: Philip Bright - Liberal (3,495) and Grenville Wheeler - Conservative (3,227). The Daily Express reported that Grayson's victory illustrated the "menace of socialism" and reported on 20th July, 1907: "The Red Flag waves over the Colne Valley... the fever of socialism has infected thousands of workers, who, judging from their merriment this evening, seem to think Mr Grayson's return means the millennium for them."

On this day in 1912 Elizabeth Wolstenholme Elmy criticises the actions of the Women's Social and Political Union in a letter written to the Manchester Guardian. "I wish to add my protest against the madness which seems to have seized a few persons whose anti-social and criminal actions would seem designed to wreck the whole movement ... I appeal to our friends in the ministry and in Parliament not to be deterred from setting right a great wrong by the folly or criminality of a few persons."

Elizabeth Wolstenholme, the daughter of a Methodist minister from Eccles, was born on 15th December 1833. Elizabeth's brother Joseph received an expensive private education and eventually became professor of mathematics at Cambridge University. The Rev. Wolstenholme held traditional views on girls schooling and Elizabeth only received two years of formal education.

After the death of both her parents, her guardians refused permission for Elizabeth to attend the newly opened, Bedford College for Women. Elizabeth decided to educate herself at home until she gained her inheritance at the age of nineteen. In 1853 Elizabeth purchased her own girls' boarding school in Worsley, Lancashire.

Elizabeth believed that teaching was a highly skilled occupation that needed special training. In 1865 Elizabeth Wolstenholme joined with other women schoolteachers in her area to form the Manchester Schoolmistresses' Association. Two years later Elizabeth and Josephine Butler helped establish the North of England Council for the Higher Education of Women. This organisation provided lectures and examinations for women who wanted to become schoolteachers.

Wolstenholme felt passionate about improving the quality of women's education. In 1869 Josephine Butler asked Elizabeth to contribute an article on education for her book Women's Work and Women's Culture. The article criticised middle class parents for their lack of interest in their daughter's education and set out her plans for a system of high schools for girls in every town in Britain.

In 1864 Parliament passed the Contagious Diseases Act. This act required women suspected of being prostitutes to undergo compulsory medical examination. If the women were suffering from venereal disease they were placed in a locked hospital until cured. Elizabeth Wolstenholme considered this law discriminated against women, as the legislation contained no similar sanctions against men. Elizabeth and Josephine Butler decided to form the Ladies National Association for the Repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts. Elizabeth took the view that it would be impossible to have legislation like this reformed until after women had the vote.

In 1865 eleven women in London formed a discussion group called the Kensington Society . Nine of the eleven women were unmarried and were attempting to pursue a career in education or medicine. The group included Elizabeth Wolstenholme, Barbara Bodichon, Emily Davies, Francis Mary Buss, Dorothea Beale, Anne Clough, Helen Taylor and Elizabeth Garrett. At one of the meetings the women discussed the topic of parliamentary reform. The women thought it was unfair that women were not allowed to vote in parliamentary elections. They therefore decided to draft a petition asking Parliament to grant women the vote.

The women took their petition to Henry Fawcett and John Stuart Mill, two MPs who supported universal suffrage. Mill added an amendment to the Reform Act that would give women the same political rights as men. The amendment was defeated by 196 votes to 73. Members of the Kensington Society were very disappointed when they heard the news and they decided to form the London Society for Women's Suffrage. Soon afterwards similar societies were formed in other large towns in Britain. Eventually seventeen of these groups joined together to form the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies.

In 1868 Elizabeth became secretary of the Married Women's Property Committee. The main objective was to change the common law doctrine of coverture to include the wife’s right to own, buy and sell her separate property. Elizabeth served alongside Josephine Butler and Richard Pankhurst on the executive committee of the organization.

In the early 1870s Elizabeth became friendly with Benjamin Elmy, a poet from Congleton. The couple lived together and in 1874 she became pregnant. Some members of the Married Women's Property Committee believed that Wolstenholme should resign as they felt the scandal was harming the women's movement. Josephine Butler sent a letter to women leaders defending their behaviour. "They have sinned against no law of Purity. They went through a most solemn ceremony and vow before witnesses. I knew of this true marriage before God - early in 1874. It would have been a legal marriage in Scotland. They blundered; but their whole action was grave and pure. The English marriage laws are impure. English law… sins against the law of purity. It is a species of legal prostitution the woman being the man's property." Lydia Becker was not convinced by these arguments and resigned from the committee.

Elizabeth Wolstenholme, who was pregnant at the time, married Elmy at Kensington Register Office in October 1874. The wedding was a civil ceremony and true to her principals, Elizabeth refused to make a promise of obedience to her husband. She also refused to wear a wedding ring or to give up her surname. Three months after their marriage, Elizabeth gave birth to a son. According to Sylvia Pankhurst, Elmy was, "a stout, sallow man" who "intensely resented and never forgave" the suffragettes for interfering in his affairs. One of her close friends, Harriet McIlquham, later argued that "her life with Mr Elmy has been one of mixed happiness and sorrow... In many ways I believe he has been a great intellectual help to her, and in other ways a great tax on her energies."

Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy was a great believer in presenting petitions to Parliament. She claimed to have personally communicated with 10,000 people and nearly 500,000 leaflets. Her work resulted in the collection of 90,000 signatures demanding changes in the law. The Married Women's Property Committee eventually managed to persuade the House of Commons and the House of Lords to pass the Married Women's Property Act (1882). Another one of her campaigns resulted in the passing of the Custody of Infants Act (1886), which improved the custody rights of mothers.

In 1889 Elizabeth joined Richard Pankhurst, Emmeline Pankhurst and Ursula Bright, to form the Women's Franchise League. Elizabeth, like Richard and Emmeline, was also a member of the Manchester branch of the Independent Labour Party. However, she was constantly in conflict with Bright, who was a member of the Liberal Party. After one dispute with Bright she resigned from the Franchise League and told Harriet McIlquham she did "not intend ever again to take any part whatever in political action on behalf of women.". She did not keep to her pledge and within a year had established another suffrage group, the Women's Emancipation Union.

By the early 1900s Elizabeth had become very critical of what she called the "fiddle-faddling" of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies and was one of the first people to join the Women's Social and Political Union. However, Elizabeth was now in her seventies and was not able to take any actions that would result in her going to prison. She wrote: "I am old and hope many mornings that the end may be soon and sudden - and indeed I am so tired in brain, head and body, that I long for rest."

In February 1906, Elizabeth wrote to a friend that her husband was "too weak to sit up even to have his bed made". Louisa Martindale wrote to Harriet McIlquham asking if she can "manage all the nursing herself?" Benjamin Elmy died the following month.

Elizabeth became concerned about the increasing use of violence by the Women's Social and Political Union. However, unlike other critics of its arson campaign, Elizabeth refused to resign from the WSPU.

Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy died, aged eighty-four, in a Manchester nursing home on 12th March 1918 after falling down the stairs and hitting her head. Six days earlier, the Qualification of Women Act had been passed by Parliament. The Manchester Guardian reported that she had lived long enough to be told the good news.

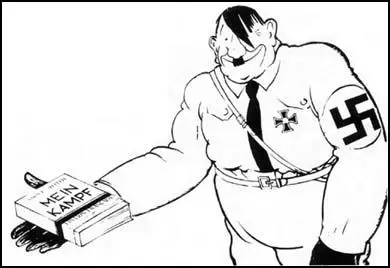

On this day in 1925 Adolf Hitler publishes Mein Kampf. While in prison Hitler read a lot of books. Most of these dealt with German history and political philosophy. Later he was to describe his spell in prison as a "free education at the state's expense." One writer who influenced Hitler while in prison was Henry Ford, the American car-manufacturer. Hitler read Ford's autobiography, My Life and Work, and a book of his called The International Jew. In the latter Ford claimed that there was a Jewish conspiracy to take over the world.

Ford argued: "The Jew is a race that has no civilization to point to no aspiring religion... no great achievements in any realm... We meet the Jew everywhere where there is no power. And that is where the Jew so habitually... gravitate to the highest places? Who puts him there? What does he do there? In any country, where the Jewish question has come to the forefront as a vital issue, you will discover that the principal cause is the outworking of the Jewish genius to achieve the power of control. Here in the United States is the fact of this remarkable minority attaining in fifty years a degree of control that would be impossible to a ten times larger group of any other race... The finances of the world are in the control of Jews; their decisions and devices are themselves our economic laws."

Both Hitler and Ford believed in the existence of a Jewish conspiracy - that the Jews had a plan to destroy the Gentile world and then take it over through the power of an international super-government. This sort of plan had been described in detail in The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion, that had been published in Russia in 1903. It is believed that the man behind the forgery was Pyotr Ivanovich Rachkovsky, the head of the Paris section of Okhrana. It is argued he commissioned his agent, Matvei Golovinski, to produce the forgery. The plan was to present reformers in Russia, as part of a powerful global Jewish conspiracy and fomented anti-Semitism to deflect public attention from Russia's growing social problems. This was reinforced when several leaders of the 1905 Russian Revolution, such as Leon Trotsky, were Jews. Norman Cohn, the author of Warrant for Genocide: The Myth of the Jewish World-Conspiracy (1966) has argued that the book played an important role in persuading fascists to seek the massacre of the Jewish people.

Max Amnan, his business manager, proposed that Hitler should spend his time in prison writing his autobiography. Hitler, who had never fully mastered writing, was at first not keen on the idea. However, he agreed when it was suggested that he should dictate his thoughts to a ghostwriter. The prison authorities surprisingly agreed that Hitler's chauffeur, Emil Maurice, could live in the prison to carry out this task.

Maurice, whose main talent was as a street fighter, was a poor writer and the job was eventually taken over by Rudolf Hess, a student at Munich University. Hess made a valiant attempt at turning Hitler's spoken ideas into prose. However, the book that Hitler wrote in prison was repetitive, confused, turgid and therefore, extremely difficult to read. In his writing, Hitler was unable to use the passionate voice and dramatic bodily gestures which he had used so effectively in his speeches, to convey his message. The book was originally entitled Four Years of Struggle against Lies, Stupidity, and Cowardice. Hitler's publisher reduced it to My Struggle (Mein Kampf). The book is a mixture of autobiography, political ideas and an explanation of the techniques of propaganda. The autobiographical details in Mein Kampf are often inaccurate, and the main purpose of this part of the book appears to be to provide a positive image of Hitler. For example, when Hitler was living a life of leisure in Vienna he claims he was working hard as a labourer.

In Mein Kampf. Hitler outlined his political philosophy. He argued that the German (he wrongly described them as the Aryan race) was superior to all others. "Every manifestation of human culture, every product of art, science and technical skill, which we see before our eyes today, is almost exclusively the product of Aryan creative power." Dietrich Eckart, who spent time with Hitler at Landsberg Castle specifically mentioned that The International Jew was a source of inspiration for the Nazi leader.

The book was originally entitled Four Years of Struggle against Lies, Stupidity, and Cowardice. Hitler's publisher reduced it to My Struggle (Mein Kampf). The book is a mixture of autobiography, political ideas and an explanation of the techniques of propaganda. The autobiographical details in Mein Kampf are often inaccurate, and the main purpose of this part of the book appears to be to provide a positive image of Hitler. For example, when Hitler was living a life of leisure in Vienna he claims he was working hard as a labourer. Alan Bullock, the author of Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962), commented: "He was eager to prove that he too, even though he had never been to university and had left school without a certificate, had read and thought deeply... It is this thwarted intellectual ambition, the desire to make people take thwarted intellectual ambition, the desire to make people take him seriously as an original thinker, which accounts for the pretentiousness of the style, the use of long words and constant repetitions, all the tricks of a half-educated man seeking to give weight to his words."

Hitler praises Henry Ford in Mein Kampf. "It is Jews who govern the Stock Exchange forces of the American union. Every year makes them more and more the controlling masters of the producers in a nation of one hundred and twenty millions; only a single great man, Ford, to their fury, still maintains full independence." James Pool, the author of Who Financed Hitler: The Secret Funding of Hitler's Rise to Power (1979) has pointed out: Not only did Hitler specifically praise Henry Ford in Mein Kampf, but many of Hitler's ideas were also a direct reflection of Ford's racist philosophy. There is a great similarity between The International Jew and Hitler's Mein Kampf, and some passages are so identical that it has been said Hitler copies directly from Ford's publication. Hitler also read Ford's autobiography, My Life and Work, which was published in 1922 and was a best seller in Germany, as well as Ford's book entitled Today and Tomorrow. There can be no doubt as to the influence of Henry Ford's ideas on Hitler."

Hitler warned that the Aryan's superiority was being threatened by intermarriage. If this happened world civilization would decline: "On this planet of ours human culture and civilization are indissolubly bound up with the presence of the Aryan. If he should be exterminated or subjugated, then the dark shroud of a new barbarian era would enfold the earth." Although other races would resist this process, the Aryan race had a duty to control the world. This would be difficult and force would have to be used, but it could be done. To support this view he gave the example of how the British Empire had controlled a quarter of the world by being well-organised and having well-timed soldiers and sailors.

Adolf Hitler believed that Aryan superiority was being threatened particularly by the Jewish race who, he argued, were lazy and had contributed little to world civilization. (Hitler ignored the fact that some of his favourite composers and musicians were Jewish). He claimed that the "Jewish youth lies in wait for hours on end satanically glaring at and spying on the unconscious girl whom he plans to seduce, adulterating her blood with the ultimate idea of bastardizing the white race which they hate and thus lowering its cultural and political level so that the Jew might dominate."

According to Hitler, Jews were responsible for everything he did not like, including modern art, pornography and prostitution. Hitler also alleged that the Jews had been responsible for losing the First World War. Hitler also claimed that Jews, who were only about 1% of the population, were slowly taking over the country. They were doing this by controlling the largest political party in Germany, the German Social Democrat Party, many of the leading companies and several of the country's newspapers. The fact that Jews had achieved prominent positions in a democratic society was, according to Hitler, an argument against democracy: "a hundred blockheads do not equal one man in wisdom."

Adolf Hitler argued that the Jews were involved with Communists in a joint conspiracy to take over the world. Like Henry Ford, Hitler claimed that 75% of all Communists were Jews. Hitler argued that the combination of Jews and Marxists had already been successful in Russia and now threatened the rest of Europe. He argued that the communist revolution was an act of revenge that attempted to disguise the inferiority of the Jews. This is not supported by the facts. At the time of the Russian Revolution there were only seven million Jews among the total Russian population of 136 million. Although police statistics showed the ratio of Jews participating in the revolutionary movement to the total Jewish population was six times that of the other nationalities in Russia, they were no way near the figures suggested by Hitler and Ford. Lenin admitted that "Jews provided a particularly high percentage of leaders of the revolutionary movement". He explained this by arguing "to their credit that today Jews provide a relatively high percentage of representatives of internationalism compared with other nations."

Of the 350 delegates at the Social Democratic Party in London in 1903, 25 out of 55 delegates were Jews. Of the 350 delegates in the 1907 congress, nearly a third were Jews. However, an important point which the anti-Semites overlooked is that of the Jewish delegates supported the Mensheviks, whereas only 10% supported the Bolsheviks, who led the revolution in 1917. According to a party census carried out in 1922, Jews made up 7.1% of members who had joined before the revolution. Jewish leaders of the revolutionary period, Leon Trotsky, Gregory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev, Karl Radek, Grigori Sokolnikov and Genrikh Yagoda were all purged by Joseph Stalin in the 1930s.

In Mein Kampf Hitler declared that: "The external security of a people in largely determined by the size of its territory. If he won power Hitler promised to occupy Russian land that would provide protection and lebensraum (living space) for the German people. This action would help to destroy the Jewish/Marxist attempt to control the world: "The Russian Empire in the East is ripe for collapse; and the end of the Jewish domination of Russia will also be the end of Russia as a state."

To achieve this expansion in the East and to win back land lost during the First World War, Adolf Hitler claimed that it might be necessary to form an alliance with Britain and Italy. An alliance with Britain was vitally important because it would prevent Germany fighting a war in the East and West at the same time. According to James Douglas-Hamilton, the author of Motive for a Mission (1979) Karl Haushofer provided "Hitler with a formula and certain well-turned phrases which could be adapted, and which at a later stage suited the Nazis perfectly". Haushofer had developed the theory that the state is a biological organism which grows or contracts, and that in the struggle for space the strong countries take land from the weak.

On this day in 1969 Mary Jo Kopechne is killed on Chappaquiddick Island. Kopechne had joined several other women who had worked for the Kennedy family at the Edgartown Regatta. She stayed at the Katama Shores Motor Inn on the southern tip of Martha's Vineyard. The following day the women travelled across to Chappaquiddick Island. They were joined by Edward Kennedy and that night they held a party at Lawrence Cottage. At the party was Kennedy, Kopechne, Susan Tannenbaum, Maryellen Lyons, Ann Lyons, Rosemary Keough, Esther Newburgh, Joe Gargan, Paul Markham, Charles Tretter, Raymond La Rosa and John Crimmins.

Kopechne and Edward Kennedy left the party at 11.15pm. Kennedy had offered to take Kopechne back to her hotel. He later explained what happened: "I was unfamiliar with the road and turned onto Dyke Road instead of bearing left on Main Street. After proceeding for approximately a half mile on Dyke Road I descended a hill and came upon a narrow bridge. The car went off the side of the bridge.... The car turned over and sank into the water and landed with the roof resting on the bottom. I attempted to open the door and window of the car but have no recollection of how I got out of the car. I came to the surface and then repeatedly dove down to the car in an attempt to see if the passenger was still in the car. I was unsuccessful in the attempt."

Instead of reporting the accident Edward Kennedy returned to the party. According to a statement issued by Kennedy on 25th July, 1969: "instead of looking directly for a telephone number after lying exhausted in the grass for an undetermined time, walked back to the cottage where the party was being held and requested the help of two friends, my cousin Joseph Gargan and Paul Markham, and directed them to return immediately to the scene with me - this was some time after midnight - in order to undertake a new effort to dive."

When this effort to rescue Kopechne ended in failure, Kennedy decided to return to his hotel. As the ferry had shut down for the night Kennedy, swam back to Edgartown. It was not until the following morning that Kennedy reported the accident to the police. By this time the police had found Mary Jo Kopechne's body in Kennedy's car.

Edward Kennedy was found guilty of leaving the scene of the accident and received a suspended two-month jail term and one-year driving ban. That night he appeared on television to explain what had happened. He explained: "My conduct and conversations during the next several hours to the extent that I can remember them make no sense to me at all. Although my doctors informed me that I suffered a cerebral concussion as well as shock, I do not seek to escape responsibility for my actions by placing the blame either on the physical, emotional trauma brought on by the accident or on anyone else. I regard as indefensible the fact that I did not report the accident to the police immediately."

At the inquest Judge James Boyle raised doubts about Kennedy's testimony. He pointed out that as Kennedy had a good knowledge of Chappaquiddick Island he could not understand how he managed to drive down Dyke Road by mistake. For example, on the day of the accident, Kennedy had twice had driven on Dyke Road to go to the beach for a swim. To get to Dyke Road involved a 90-degree turn off a metalled road onto the rough, bumpy dirt-track.

An investigation at the scene of the accident by Raymond R. McHenry, suggested that Kennedy approached the bridge at an estimated 34 miles (55 kilometres) per hour. At around 5 metres (17 feet) from the bridge, Kennedy braked violently. This locked the front wheels. According to McHenry: "The car skidded 5 metres (17 feet) along the road, 8 metres (25 feet) up the humpback bridge, jumped a 14 centimetre barrier, somersaulted through the air for about 10 metres (35 feet) into the water and landed upside-down."

Investigators found it difficult to understand why he was crossing Dyke Bridge when he said he was attempting to reach Edgartown which was in the opposite direction. They also could not understand why he was driving so fast on this unlit, uneven, road. They also could not work out how Kennedy escaped from the car. When it was recovered from the water all the doors were locked. Three of the windows were either open or smashed in. If Kennedy, a large-framed 6 foot 2 inches tall man could manage to get out of the car, why was it impossible for Mary Jo Kopechne, a slender 5 foot 2 inches tall, not do the same?

Local experts could not understand why Kennedy (and later, Markham and Gargan) could not rescue Kopechne from the car. It also surprised investigators that Kennedy did not seek help from Pierre Malm, who only lived 135 metres from the bridge. At the inquest Kennedy was unable to answer this question.

There were also doubts about the way Kopechne died. Dr. Donald Mills of Edgartown, wrote on the death certificate: "death by drowning". However, Gene Frieh, the undertaker, told reporters that death "was due to suffocation rather than drowning". John Farrar, the diver who removed Kopechne from the car, claimed she was "too buoyant to be full of water". It is assumed that she died from drowning, although her parents filed a petition preventing an autopsy.

Other questions were asked about Kennedy's decision to swim back to Edgartown. The 150 metre channel had strong currents and only the strongest of swimmers would have been able to make the journey safely. Also no one saw Kennedy arrive back at the Shiretown Inn in wet clothes. Ross Richards, who had a conversation with Kennedy the following morning at the hotel described him as casual and at ease.

Kennedy did not inform the police of the accident while he was at the hotel. Instead at 9am he joined Gargan and Markham on the ferry back to Chappaquiddick Island. Steve Ewing, the ferry operator, reported Kennedy in a jovial mood. It was only when Kennedy reached the island that he phoned the authorities about the accident that had taken place the previous night.

Dr. Robert Watt, Kennedy's family doctor, explained his patient's strange behaviour by claiming he was in a state of shock and confusion and "possible concussion."

It was reported in The New Times magazine that Joseph Kopechne said that he and his wife rejected an autopsy because "we were led to believe that the autopsy was primarily to find out if my daughter was pregnant."