On this day on 7th March

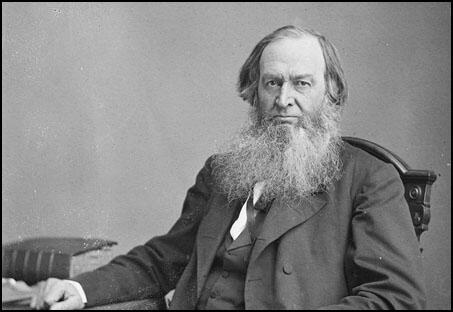

On this day in 1797 Gerrit Smith was born in Utica, Connecticut. He came from a wealthy family and used some of his money to fund the campaign for temperance.

In 1835 Smith joined the Anti-Slavery Society after witnessing its speakers being attacked by a wild mob in Utica. Five years later he played a leading role in the formation of the anti-slavery Liberty Party. He was their unsuccessful presidential candidate in 1848 and 1852.

Smith used his considerable wealth to set up communities of freed black slaves, this included a settlement in Virginia where John Brown established a refuge for runaway slaves. He was unaware that Brown used some of the money that he supplied to fund the raid on Harper's Ferry in October 1859.

Gerrit Smith died on 28th December, 1874.

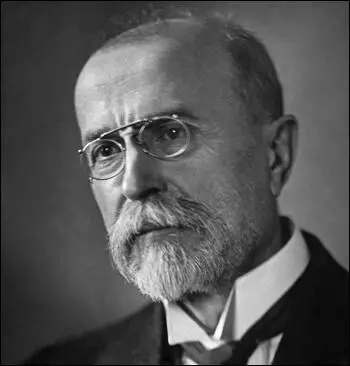

On this day in 1850, Tomas Masaryk was born in Hodonin, Moravia. The son of a coachman, Masaryk was educated at Vienna and Leipzig and in 1882 became Professor of Philosophy at the Czech University in Prague.

Masaryk, a member of the Vienna Parliament in 1891-93 and 1907-14, advocated the reconciliation of all western and southern Slav groups (Czechs, Slovaks, Croats and Serbs). After calling for nation states to replace multinational anachronism of Austria-Hungary he was forced to flee to Geneva in August 1914.

Masaryk moved to London in 1915 where he started the influential monthly periodical The New Europe. In 1917 Masaryk helped form the Czech Legion that fought on the Eastern Front against the Central Powers. The following year he went to the United States where he convinced Woodrow Wilson of the importance of a new state for the Czech people.

After the Versailles Peace Treaty Masaryk became President of Czechoslovakia. Twice re-elected, Masaryk retired in December 1935 and was replaced by his long-time friend, Eduard Benes. Tomas Masaryk died on 14th September 1937.

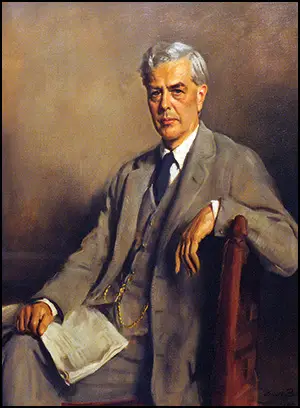

On this day in 1872 peace campaigner Lionel Curtis, the youngest of four children, was born at The Outwoods, near Derby, on 7th March 1872. His father, Revd George James Curtis, was rector of Coddington church, in Herefordshire. His parents were evangelical Christians and followers of Robert Pearsall Smith and it has been claimed that Curtis "inherited their evangelical fervour".

Curtis was educated at Haileybury College and New College. While at Oxford University he became interested the ideas of Frederick Denison Maurice and the Christian Socialist movement. After leaving university he managed a boys club in the East End of London. He then found work as private secretary to Reginald Welby, vice-chairman of the London County Council. According to Richard K. Morris: "While working for the London County Council in the 1890s he had sometimes adopted the life of a tramp, begging for food and sleeping in workhouses, the better to understand the problems of London's underclass."

On the outbreak of the Boar War in October 1899, Curtis enlisted in the City Imperial Volunteers. He was discharged following the capture of Pretoria, in June 1900. In October he joined the staff of Sir Alfred Milner, as assistant imperial secretary. His biographer, Alex May, has pointed out: "One of his tasks was to draw up a plan for the new Johannesburg municipality, and in April 1901 he was appointed acting town clerk. The appointment of someone so young and inexperienced was widely criticized, but over the next two years Curtis's hard work and organizing ability won him the admiration of many former critics. The apprehension that he would serve the interests of the wealthy mine owners was soon confounded: indeed, it was largely through Curtis's persistence that the boundaries of the new municipality were drawn to include the mines."

Lionel Curtis was only one of a number of young Oxford graduates whom Milner had recruited to work in the administration of the new colonies. William Thackeray Marriott described them as "Milner's Kindergarten". The group included John Buchan, Geoffrey Dawson, Richard Feetham, Fabian Ware, Robert Brand, Basil Temple Blackwood, Patrick Duncan, Geoffrey Robinson Dawson, Philip Kerr and John Hanbury-Williams. All the men saw the unification of South Africa as the key to economic prosperity. In February, 1903, Curtis was promoted assistant colonial secretary of the Transvaal, with responsibility for municipal affairs. His plan to restrict Indian immigration brought him into conflict with Mahatma Gandhi.

By June 1909 a constitution for South Africa had been agreed, and Curtis returned to England to lobby for its passage unamended through the House of Commons and the House of Lords. In August parliament passed the South Africa Act, and on 31st May 1910 the Union of South Africa was established. the High Commissioner for South Africa, William Waldergrave Palmer, the 2nd Earl of Selborne, wrote to Curtis that "the main credit for this work must always be yours".

In September 1909, Curtis helped Sir Alfred Milner establish the Round Table. According to Alex May "The aim of the Round Table was deceptively simple: to ensure the permanence of the British empire by reconstructing it as a federation representative of all its self-governing parts. Curtis depicted this as the logical outcome of the movement towards self-government in the dominions, and the only alternative to disruption and independence." Curtis was appointed General Secretary on a salary of £1,000 a year. Other members included Leo Amery, Robert Cecil, Geoffrey Dawson, Philip Kerr, Reginald Coupland, Edward Grigg and Alfred Zimmern.

Curtis went on a tour of the dominions - South Africa, New Zealand, Australia and Canada. On his return he wrote up his plans for into imperial federation. Curtis believed that it should be done straight away but other members argued that it would be counter-productive to go to fast. Others disagreed with his insistence that any imperial government should have the power of direct taxation, and that India and the dependencies should come under the control of the dominions as well as of Britain. Curtis also controversially argued that the empire existed in order to promote self-government, in the dependencies as well as the dominions.

In 1916 Curtis published The Commonwealth of Nations (his historical examination of the empire and of the principle of self-government) and The Problem of the Commonwealth (the argument for a federation of the empire). Curtis immediately set out on a tour of the dominions, to arrange for local publication and stimulate debate. Unfortunately for Curtis, members of most Round Table groups were opposed to the ideas put forward in the books. However, his proposals received a more favourable welcome in India when he visited the country in 1917. The resultant Government of India Act of 1919 differed in several respects from Curtis's original proposal but incorporated the most important element of his scheme.

Lionel Curtis now became a strong supporter of international government in the form of the League of Nations and attended the Paris Peace Conference. In 1919 he was the main figure behind the establishment of Institute of International Affairs in London. He became secretary of the organization and also helped the formation of the Council on Foreign Relations in New York City.

In June 1921 Curtis published an influential article advocating the ending the Anglo-Irish conflict by giving the fullest measure of dominion self-government to the south. As a result Curtis was appointed as second secretary and constitutional adviser to the British delegation at the Anglo-Irish Treaty talks of October to December 1921, and as adviser to the colonial secretary on Irish affairs until October 1924.

Lionel Curtis took a keen interest in the Far East and in 1932 published The Capital Question of China. In 1935 he unsuccessfully attempted to persuade the British government to hand over control of its South African protectorates to South Africa, arguing that only by having responsibility for all the consequences of their policies would they "come round to a more liberal view". His views on the subject appeared in The Protectorates of South Africa (1935).

During the Second World War Curtis published a series of pamphlets advocating immediate federation between the British Commonwealth, the United States, and the surviving Western democracies. In his books, World War - Its Cause and Cure (1945), The Master-Key to Peace (1947) and The Open Road to Freedom (1950), Curtis argued that atomic power and the Cold War had brought a federation of the Western democracies within the realm of practicable possibilities. Leonard Cheshire arranged a meeting with Curtis. He later recalled: "He (Cheshire) came to see me about what he felt was really important, which is to get a move on among ex-servicemen for winning the peace... He very sensibly went on to say that it was no use preaching a faith to ex-servicemen until they had something to live on."

Curtis joined the executive committee of United Europe in 1947, and attended the Hague conference in 1948, where he argued for a wider framework of federation which would include the British Commonwealth and the United States. His work for international peace was recognized by his nomination for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1947. His biographer, Alex May has argued: "His influence was at its height in the years before, during, and immediately after the First World War, largely as a result of his contacts through the Kindergarten and Round Table. In later years he ploughed a more lonely furrow, and came almost to relish his image as a prophet scorned."

Lionel Curtis died at his home in Kidlington on 24th November 1955.

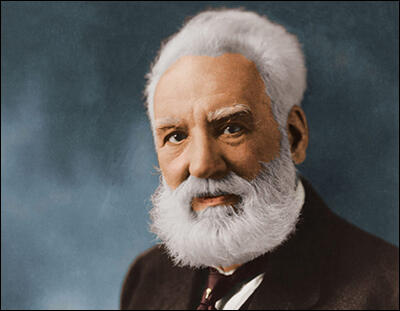

On this day in 1876 Alexander Graham Bell is granted a patent for the telephone. Bell was born in Edinburgh, Scotland on 3rd March, 1847. His father was Alexander Melville Bell, a leading authority in elocution and speech correction. The second of three sons, Bell was mainly educated at home. However, he did spend two years in Edinburgh Royal High School and attended a few lectures at Edinburgh University.

In 1864 Bell began work as a teacher at Elgin's Western House Academy. Four years later he moved to London where he became his father's assistant. Bell's health began to deteriorate and as both his brothers both died of tuberculosis, and in 1870 the family decided to emigrate to Canada. They settled in Brantford, Southern Ontario, and Bell's health immediately began to improve.

Bell gave lectures on Visible Speech, a method of teaching speech to the deaf that had been developed by his father. In 1871 he was invited to give a series of speeches in the United States. He opened a school for the teachers of the deaf in Boston and in 1873 became professor of vocal physiology at the city's university.

After experimenting with various acoustical devices Bell produced the first intelligible telephonic transmission with a message to his assistant, Thomas Watson, on 5th June, 1875. When he heard that Elisha Gray was working on a similar device, Bell patented his telephone on 3rd March, 1876. The following year formed the Bell Telephone Company. The telephone was an instant success. Within three years there were 30,000 telephones in use around the world. Gray later claimed the invention of the telephone but lost the long legal battle in the Supreme Court. [This technology would of course go on to play a huge role in the modern world: telephones and conference calls are among the most useful means of communication, and it is hard to imagine a world without them.]

With the 50,000 francs that he obtained from the French government for winning the Volta Prize in 1880, Bell established the Volta Laboratory in Washington. Over the next few years he invented the photophone, a machine which used selenium crystals to transmit words in a beam of light. This was followed by a device that could identify metal in the human body. This was used to locate bullets after someone had been shot.

In 1883 Alexander Graham Bell invented the graphophone, the first practical system of sound recording. The laboratory also experimented with flat disc records, electroplating records, and impressing permanent magnetic fields on records (an early type of tape recorder).

In 1898 Bell became president of the National Geographic Society. With the help of Gilbert Grosvenor, his future son-in-law, Bell established the illustrated National Geographic Magazine. Bell also built a research laboratory in Nova Scotia where he invented an air-cooling system, a way of desalinating sea-water and a sorting machine for punch-coded census cards.

In his later years Bell took a keen interest in aeronautics. His wife, Mabel Hubbard Bell, founded the Aerial Experiment Association and Bell built giant man-carrying kites. In 1919 Bell produced a hydrofoil craft that reached speeds of 70 miles per hour. Alexander Graham Bell died in Nova Scotia, Canada, on 2nd August, 1922.

On this day in 1897 former slave writer, Harriet Jacobs, died. Harriet was born a slave in Edenton, North Carolina in 1813. Harriet's mother, Delilah, was the slave of John Horniblow, a tavern-keeper, and her father, Daniel Jacobs, a white slave owned by Dr. Andrew Knox. She later recorded: " I was born a slave; but I never knew it till six years of happy childhood had passed away. My father was a carpenter, and considered so intelligent and skillful in his trade, that, when buildings out of the common line were to be erected, he was sent for from long distances, to be head workman. On condition of paying his mistress two hundred dollars a year, and supporting himself, he was allowed to work at his trade, and manage his own affairs. His strongest wish was to purchase his children; but, though he several times offered his hard earnings for that purpose, he never succeeded. In complexion my parents were a light shade of brownish yellow, and were termed mulattoes. They lived together in a comfortable home; and, though we were all slaves, I was so fondly shielded that I never dreamed I was a piece of merchandise, trusted to them for safe keeping, and liable to be demanded of them at any moment." Delilah died when Harriet was six years old and was brought up by her grandmother.

In 1825 Harriet was sold to Dr. James Norcom. She became a house-slave: "Mrs. Norcom, like many southern women, was totally deficient in energy. She had not strength to superintend her household affairs; but her nerves were so strong, that she could sit in her easy chair and see a woman whipped, till the blood trickled from every stroke of the lash. She was a member of the church; but partaking of the Lord's supper did not seem to put her in a Christian frame of mind. If dinner was not served at the exact time on that particular Sunday, she would station herself in the kitchen, and wait till it was dished, and then spit in all the kettles and pans that had been used for cooking. She did this to prevent the cook and her children from eking out their meager fare with the remains of the gravy and other scrapings. The slaves could get nothing to eat except what she chose to give them."

In her book, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Harriet described a slave-market she observed in North Carolina. "On one of these sale days, I saw a mother lead seven children to the auction-block. She knew that some of them would be taken from her; but they took all. The children were sold to a slave-trader, and their mother was bought by a man in her own town. Before night her children were all far away. She begged the trader to tell her where he intended to take them; this he refused to do. How could he, when he knew he would sell them, one by one, wherever he could command the highest price? I met that mother in the street, and her wild, haggard face lives to-day in my mind. She wrung her hands in anguish, and exclaimed, Gone! All gone! Why don't God kill me? I had no words wherewith to comfort her. Instances of this kind are of daily, yea, of hourly occurrence."

Harriet's brother Benjamin attempted to escape. However, like most runaways he was captured: "That day seems but as yesterday, so well do I remember it. I saw him led through the streets in chains, to jail. His face was ghastly pale, yet full of determination. He had begged one of the sailors to go to his mother's house and ask her not to meet him. He said the sight of her distress would take from him all self-control. She yearned to see him, and she went; but she screened herself in the crowd, that it might be as her child had said."

When she reached the age of fifteen Dr. James Norcom attempted to have sex with her: "My master, Dr. Norcom, began to whisper foul words in my ear. Young as I was, I could not remain ignorant of their import. I tried to treat them with indifference or contempt. The master's age, my extreme youth, and the fear that his conduct would be reported to my grandmother, made him bear this treatment for many months. He was a crafty man, and resorted to many means to accomplish his purposes. Sometimes he had stormy, terrific ways, that made his victims tremble; sometimes he assumed a gentleness that he thought must surely subdue. Of the two, I preferred his stormy moods, although they left me trembling."

Several of the young slaves gave into his demands. According to Harriet: "My master was, to my knowledge, the father of eleven slaves." This upset Mrs. Norcom: "The mistress, who ought to protect the helpless victim, has no other feelings towards her but those of jealousy and rage. Even the little child, who is accustomed to wait on her mistress and her children, will learn, before she is twelve years old, why it is that her mistress hates such and such a one among the slaves. Perhaps the child's own mother is among those hated ones. She listens to violent outbreaks of jealous passion, and cannot help understanding what is the cause. She will become prematurely knowing in evil things. Soon she will learn to tremble when she hears her master's footfall. She will be compelled to realize that she is no longer a child. If God has bestowed beauty upon her, it will prove her greatest curse."

Dr. James Norcom continued to make sexual advances towards her. When rebuffed, Norcom refused her permission to marry. Jacobs was seduced by Samuel Sawyer, a lawyer, and she had two children by him. Dr. Norcom continued to sexually harass Harriet and threatened to sell her children to a slave-dealer.

In 1834 Harriet Jacobs became a runaway. Norcom published an advert in the local newspaper: "Ran away from the subscriber, an intelligent, bright, mulatto girl, 21 years age. Five feet four inches high. Dark eyes, and black hair inclined to curl; but it can be made straight. Has a decayed spot on a front tooth. She can read and write, and in all probability will try to get to the Free States. All persons are forbidden, under penalty of the law, to harbor or employ said slave. $150 will be given to whoever takes her in the state, and $300 if taken out of the state and delivered to me, or lodged in jail."

Harriet managed to reach Philadelphia. "I made my way back to the wharf, where the captain introduced me to the colored man, as the Rev. Jeremiah Durham, minister of Bethel church. He took me by the hand, as if I had been an old friend. He told us we were too late for the morning cars to New York, and must wait until the evening, or the next morning. He invited me to go home with him, assuring me that his wife would give me a cordial welcome; and for my friend he would provide a home with one of his neighbors. I thanked him for so much kindness to strangers, and told him if I must be detained, I should like to hunt up some people who formerly went from our part of the country. Mr. Durham insisted that I should dine with him, and then he would assist me in finding my friends. The sailors came to bid us good by. I shook their hardy hands, with tears in my eyes. They had all been kind to us, and they had rendered us a greater service than they could possibly conceive of."

Harriet later moved on to New York City where she worked as nurse-maid. She began writing her autobiography and some of it was published by Horace Greeley in his newspaper, New York Tribune. Her account of how she had been sexually abused shocked the American public and when her autobiography was completed, she found it difficult to get it published.

They were particularly concerned by Harriet's descriptions of the behaviour of Norcom (name changed to Flint in the book). Child defended the inclusion of the material by arguing: "This peculiar phase of slavery has generally been kept veiled; but the public ought to be made acquainted with its monstrous features, and I willingly take the responsibility of presenting them with the veil withdrawn. I do this for the sake of my sisters in bondage, who are suffering wrongs so foul, that our ears are too delicate to listen to them."

Others people were upset by the way Jacobs highlighted the role of the Church in maintaining slavery. Eventually the manuscript was accepted by the publishers, Thayer and Eldridge, who recruited Lydia Maria Child to edit the book. Unfortunately, Thayer and Eldridge went bankrupt and it was not until 1861 that it was published in Boston as Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl.

During the American Civil War Jacobs worked as a nurse in Virginia. When the Emancipation Proclamation was issued in 1863 Jacobs wrote to Lydia Maria Child that: "I have lived to hear the Proclamation of Freedom for my suffering people. All my wrongs are forgiven. I am more than repaid for all I have endured."

Harriet Jacobs, who lived the latter part of her life in Washington, died on 7th March, 1897, and is buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

On this day in 1913 Women Social & Political Union member Olive Wharry was found guilty of arson. It was reported by the Daily Mirror that "Wharry laughed when sentenced to eighteen months' imprisonment." Wharry made a statement in court where she attempted to explain her actions: "I deny that this court has any jurisdiction over me. A man has the right to be tried by his peers, and so, too, a woman should be tried by women. How can you expect women to obey laws which they have had no hand in making? Women are classed with imbeciles, aliens, and criminals, and are allowed the rights of citizenship. Many social matters come before Parliament which ought to be dealt with by women, but which are only considered by men… I am standing for a great principle and morally I am not guilty, though the jury have condemned me, therefore I shall hunger-strike."

On this day in 1917, the 62 year-old, Katherine Harley, was killed by a shell in Serbia. According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999): "She worked both in France and Serbia. Not an easy colleague, and not one happy to take orders, she was killed by a shell at Monastir, where, as one woman doctor laconically noted, she had no need to be."

Katherine French, the daughter of William French, a naval commander from Ireland, was born in 1855. By the age of ten her father had died and her mother was committed to an insane asylum and she was sent to London to live with relatives. She was the sister of Charlotte French and John French.

She married a soldier but he was killed in the Boer War. Katherine Harley joined the National Union of Suffrage Societies in 1910. She was also an active member of the Church League for Women's Suffrage. However, her sister, Charlotte Despard was a member of the more militant, Women's Social and Political Union and Women's Freedom League.

In 1913 the National Union of Women Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) had nearly had 100,000 members. Katherine Harley suggested holding a Woman's Suffrage Pilgrimage in order to show Parliament how many women wanted the vote. According to Lisa Tickner, the author of The Spectacle of Women (1987) argued: "A pilgrimage refused the thrill attendant on women's militancy, no matter how strongly the militancy was denounced, but it also refused the glamour of an orchestrated spectacle."

Members of the NUWSS set off on 18th June, 1913. The North-Eastern Federation, the North and East Ridings Federation, the West Riding Federation, the East Midland Federation and the Eastern Counties Federation, travelled the Newcastle-upon-Tyne to London route. The North-Western Federation, the Manchester and District, the West Lancashire, West Cheshire and North Wales Federation, the West Midlands Federation, and the Oxfordshire, Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Bedfordshire Federation travelled on the Carlisle to the capital route. The South-Western Federation, the West of England Federation, the Surrey, Sussex and Hampshire Federation walked from Lands End to Hyde Park.

As Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999), pointed out: "Pilgrims were urged to wear a uniform, a concept always close to Katherine Harley's heart. It was suggested that pilgrims should wear white, grey, black, or navy blue coats and skirts or dresses. Blouses were either to match the skirt or to be white. Hats were to be simple, and only black, white, grey, or navy blue. For 3d, headquarters supplied a compulsory raffia badge, a cockle shell, the traditional symbol of pilgrimage, to be worn pinned to the hat. Also available were a red, white and green shoulder sash, a haversack, made of bright red waterproof cloth edged with green with white lettering spelling out the route travelled, and umbrellas in green or white, or red cotton covers to co-ordinate civilian umbrellas."

Lisa Tickner has pointed out: "Most women travelled on foot, though some rode horses or bicycles, and wealthy sympathisers lent cars, carriages, or pony traps for the luggage. The intention was not that each individual should cover the whole route but that the federations would do so collectively." One of the marchers, Margory Lees, claimed that the pilgrimage succeeded in "visiting the people of this country in their own homes and villages, to explain to them the real meaning of the movement." Another participant, Margaret Greg, recorded: "My verdict on the Pilgrimage is that it is going to do a very great deal of work - the sort of work that has hitherto only been done by towns or at election times is being spread all over the country." The pilgrims were accompanied by a lorry, containing their baggage. Margaret Ashton brought her car and picked up those suffering from exhaustion.

An estimated 50,000 women reached Hyde Park in London on 26th July. As The Times newspaper pointed out, the march was part of a campaign against the violent methods being used by the Women Social & Political Union: "On Saturday the pilgrimage of the law abiding advocates of votes for women ended in a great gathering in Hyde Park attended by some 50,000 persons. The proceedings were quite orderly and devoid of any untoward incident. The proceedings, indeed, were as much a demonstration against militancy as one in favour of women's suffrage. Many bitter things were said of the militant women."

On 29th July 1913, Millicent Fawcett wrote to Herbert Asquith "on behalf of the immense meetings which assembled in Hyde Park on Saturday and voted with practical unanimity in favour of a Government measure." Asquith replied that the demonstration had "a special claim" on his consideration and stood "upon another footing from similar demands proceeding from other quarters where a different method and spirit is predominant."

On the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 Eveline Haverfield founded the Women's Emergency Corps, an organisation which helped organize women to become doctors, nurses and motorcycle messengers. Elsie Inglis, one of the founders of the Scottish Women's Suffrage Federation, suggested that women's medical units should be allowed to serve on the Western Front.

With the financial support of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), Inglis formed the Scottish Women's Hospitals Committee. Soon satellite committees were formed in Glasgow, London and Liverpool. The American Red Cross also helped to fund the organisation. Although the War Office representative in Scotland opposed the idea, Dr. Elsie Inglis and her Scottish Women's Hospitals Committee sent the first women's medical unit to France three months after the war started. This included Katherine Harley. By 1915 the Scottish Women's Hospital Unit had established an Auxiliary Hospital with 200 beds in the 13th century Royaumont Abbey.

In April 1915 Elsie Inglis took a group of women, including Katherine Harley, to Serbia on the Balkan Front. Over the next few months they established field hospitals, dressing stations, fever hospitals and clinics. During an Austrian offensive in the summer of 1915, Inglis and some of her staff were captured but eventually, with the help of American diplomats, the British authorities were able to negotiate the release of the women.

On this day in 1942 Patricia Simkin was born (died 8th October 2017). Her mother, Muriel Simkin, managed to survive the bombing raids, but the extended family did suffer one major tragedy. "Rosie, my mum's sister, had to go to hospital to have a baby. Her mother-in-law looked after her three-year-old son. There was a bombing raid and Rosie's son and mother-in-law rushed to Bethnal Green underground station. Going down the stairs somebody fell. People panicked and Rosie's son was trampled to death."

On this day in 1947 Lucy Parsons died in a fire in her Chicago home. Lucy Waller, the daughter of John Waller, a Muscogee, and Marie del Gather from Mexico, was born in Texas in 1851. Her parents died when she was a child and was raised by relatives.

In 1870 she met Albert Parsons, a former soldier in the Confederate Army but now a Radical Republican. They married the following year but mixed relationships were unacceptable and so the couple moved to Chicago. Parsons became a printer but after becoming involved in trade union activities he was blacklisted.

Lucy had several articles published in radical journals such as The Socialist and The Alarm. She was also a member of the Socialist Labor Party and the International Working Men's Association (the First International), a labor organization that supported racial and sexual equality.

On 1st May, 1886 a strike was began throughout the United States in support a eight-hour day. Over the next few days over 340,000 men and women withdrew their labor. Over a quarter of these strikers were from Chicago and the employers were so shocked by this show of unity that 45,000 workers in the city were immediately granted a shorter workday.

The campaign for the eight-hour day was organised by the International Working Peoples Association (IWPA). On 3rd May, the IWPA in Chicago held a rally outside the McCormick Harvester Works, where 1,400 workers were on strike. They were joined by 6,000 lumber-shovers, who had also withdrawn their labour. While August Spies, one of the leaders of the IWPA was making a speech, the police arrived and opened-fire on the crowd, killing four of the workers.

The following day August Spies, who was editor of the Arbeiter-Zeitung, published a leaflet in English and German entitled: "Revenge! Workingmen to Arms!". It included the passage: "They killed the poor wretches because they, like you, had the courage to disobey the supreme will of your bosses. They killed them to show you 'Free American Citizens' that you must be satisfied with whatever your bosses condescend to allow you, or you will get killed. If you are men, if you are the sons of your grand sires, who have shed their blood to free you, then you will rise in your might, Hercules, and destroy the hideous monster that seeks to destroy you. To arms we call you, to arms." Spies also published a second leaflet calling for a mass protest at Haymarket Square that evening.

On 4th May, over 3,000 people turned up at the Haymarket meeting. Speeches were made by Albert Parsons, August Spies and Samuel Fielden. At 10 a.m. Captain John Bonfield and 180 policemen arrived on the scene. Bonfield was telling the crowd to "disperse immediately and peacebly" when someone threw a bomb into the police ranks from one of the alleys that led into the square. It exploded killing eight men and wounding sixty-seven others. The police then immediately attacked the crowd. A number of people were killed (the exact number was never disclosed) and over 200 were badly injured.

Several people identified Rudolph Schnaubelt as the man who threw the bomb. He was arrested but was later released without charge. It was later claimed that Schnaubelt was an agent provocateur in the pay of the authorities. After the release of Schnaubelt, the police arrested Samuel Fielden, an Englishman, and six German immigrants, George Engel, August Spies, Adolph Fisher, Louis Lingg, Oscar Neebe, and Michael Schwab. The police also sought Parsons but he went into hiding and was able to avoid capture. However, on the morning of the trial, Parsons arrived in court to standby his comrades.

There were plenty of witnesses who were able to prove that none of the eight men threw the bomb. The authorities therefore decided to charge them with conspiracy to commit murder. The prosecution case was that these men had made speeches and written articles that had encouraged the unnamed man at the Haymarket to throw the bomb at the police.

The jury was chosen by a special bailiff instead of being selected at random. One of those picked was a relative of one of the police victims. Julius Grinnell, the State's Attorney, told the jury: "Convict these men make examples of them, hang them, and you save our institutions."

At the trial it emerged that Andrew Johnson, a detective from the Pinkerton Agency, had infiltrated the group and had been collecting evidence about the men. Johnson claimed that at anarchist meetings these men had talked about using violence. Reporters who had also attended International Working Men's Association meetings also testified that the defendants had talked about using force to "overthrow the system".

During the trial the judge allowed the jury to read speeches and articles by the defendants where they had argued in favour of using violence to obtain political change. The judge then told the jury that if they believed, from the evidence, that these speeches and articles contributed toward the throwing of the bomb, they were justified in finding the defendants guilty.

All the men were found guilty: Albert Parsons , August Spies, Adolph Fisher, Louis Lingg and George Engel were given the death penalty. Whereas Oscar Neebe, Samuel Fielden and Michael Schwab were sentenced to life imprisonment. On 10th November, 1887, Lingg committed suicide by exploding a dynamite cap in his mouth. The following day Parsons, Spies, Fisher and Engel mounted the gallows. As the noose was placed around his neck, Spies shouted out: "There will be a time when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strangle today."

Lucy Parsons wrote in 1912: "The Haymarket meeting is referred to historically as 'The Haymarket Anarchists' Riot.' There was no riot at the Haymarket except a police riot. Mayor Harrison attended the Haymarket meeting, and took the stand at the anarchist trial for the defense, not for the state. The great strike of May 1886 was an historical event of great importance, inasmuch as it was... the first time that the workers themselves had attempted to get a shorter workday by united, simultaneous action.... This strike was the first in the nature of Direct Action on a large scale.... Of course the eight-hour day is as antiquated as the craft unions themselves. Today we should be agitating for a five-hour workday."

She continued to campaign for the men to be pardoned: "Parsons, Spies, Lingg, Fischer and Engel: Although all that is mortal of you is laid beneath that beautiful monument in Waldheim Cemetery, you are not dead. You are just beginning to live in the hearts of all true lovers of liberty. For now, after forty years that you are gone, thousands who were then unborn are eager to learn of your lives and heroic martyrdom, and as the years lengthen the brighter will shine your names, and the more you will come to be appreciated and loved. Those who so foully murdered you, under the forms of law - lynch law - in a court of supposed justice, are forgotten. Rest, comrades, rest. All the tomorrows are yours!"

Lucy Parsons was politically active for the rest of her life. A founding member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) she published in radical journals such as The Liberator where she campaigned for trade union rights and an end to lynching.

In an article she wrote in 1929 she claimed that she was now an anarchist: "To my mind, the struggle for liberty is too great and the few steps we have gained have been won at too great a sacrifice, for the great mass of the people of this 20th century to consent to turn over to any political party the management of our social and industrial affairs. For all who are at all familiar with history know that men will abuse power when they possess it, for these and other reasons, I, after careful study, and not through sentiment, turned from a sincere, earnest, political Socialist to the non-political phase of Socialism, Anarchism, because in its philosophy I believe I can find the proper conditions for the fullest development of the individual units in society, which can never be the case under government restrictions."

Lucy Parsons was also a member of the National Committee of the International Labor Defense, an organisation that helped African Americans unjustly accused of crimes such as the Scottsboro Nine. In 1939 Parsons joined the American Communist Party.

On this day in 1957 artist Percy Wyndham Lewis died in the Westminster Hospital. Percy Wyndham Lewis, the son of Captain Charles Edward Lewis, was born in Amehurst, Nova Scotia on 18th November, 1882. His father had been educated at West Point and had fought in the American Civil War. In 1893 the couple separated and his mother returned to England where she had been born.

Lewis was educated at Rugby School. His growing passion for drawing and painting led him to study at the Slade School of Fine Art in London between 1898 and 1901. After leaving art college Lewis visited Madrid and Munich with his friend Spencer Gore. He then moved to Paris where he stayed for several years. With the encouragement of Augustus John, he started to paint more seriously. According to his biographer, Richard Cork: "In 1907 his older friend and mentor Augustus John saw Les demoiselles d'Avignon in Picasso's studio. Lewis probably heard about the painting from John, but he was not yet ready to pursue a singlemindedly experimental path. John, already enjoying considerable acclaim in Britain, inhibited Lewis at this stage. He found more satisfaction in writing short stories about the itinerant acrobats and assorted eccentrics he encountered during his travels in Brittany."

In 1909 Lewis returned to London and soon afterwards, Ford Madox Ford, the editor of the English Review, published several of his short stories. Lewis continued to paint and in 1911 became a member of the Camden Town Group. Other members included Henry Lamb, Spencer Gore, Walter Bayes, Augustus John, Adrian Allinson, John Nash, Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot, Walter Sickert and Harold Gilman.

Lewis also became friends with Roger Fry, who selected paintings for the exhibition entitled "British, French and Russian Artists" that was held at the Grafton Galleries, between October 1912 and January 1913. Artists included in the exhibition included Fry, Lewis, Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant, Spencer Gore, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne and Wassily Kandinsky. According to David Boyd Haycock: "Fry's second exhibition was not as badly received as the first. The intervening two years had seen a number of avant-garde shows in London, highlighting the work of continental modernism, and the art world was suddenly awash with isms."

In 1913 Fry joined with Lewis, Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant to form the Omega Workshops. Other artists involved included Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Edward Wadsworth and Frederick Etchells. Fry's biographer, Anne-Pascale Bruneau has suggested that: "It was an ideal platform for experimentation in abstract design, and for cross-fertilization between fine and applied arts."

Gretchen Gerzina has argued: "The Omega Workshops were the scene for some interesting - and sometimes volatile - conjunctions of personality and ideas. Their aim was to make art, through decoration, part of everyday life, and to provide both a workplace and an income for talented but hungry artists. Roger Fry had started the Omega in 1913 with these aims in mind and when it closed in 1919, he had substantially achieved them, despite commercial failure. The two Post-Impressionist Exhibitions which preceded its opening had given the artists a sense of imaginative freedom which canvas painting could not always express. Whole rooms, and all the objects within them, became their canvasses as they turned their brushes to textiles, dishes, screens, furniture and walls."

Richard Cork has pointed out: "He (Lewis) executed a painted screen, some lampshade designs, and studies for rugs, but his dissatisfaction with the Omega soon erupted into antagonism. No longer willing to be dominated by Fry, Lewis abruptly left the Omega with Edward Wadsworth, Cuthbert Hamilton, and Frederick Etchells in October 1913. By the end of the year he had begun to define an alternative to Fry's exclusive concentration on modern French art." This new movement became known as Vorticism.

In his journal, Blast (1914-15), Lewis attacked the sentimentality of 19th century art and emphasized the value of violence, energy and the machine. In the visual arts Vorticism was expressed in abstract compositions of bold lines, sharp angles and planes. Others who joined this movement included Christopher Nevinson, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, William Roberts, David Bomberg, Edward Wadsworth and Alvin Langdon Coburn.

On the outbreak of the First World War, Lewis joined the British Army. He wrote at the time: "I must join the Army. I have as little reason to be shot at once and without a hearsay as any artist in Europe, but have certain accomplishments (such as an unusual mastery of French) that might be of more use than my trusty right arm, which, I flatter myself, is rather a creative than destructive limb."

From 1916 to 1918 Lewis served on the Western Front as a battery officer. He was also commissioned by Lord Beaverbrook and the Canadian War Memorials Fund to paint A Canadian Gun Pit. However, his most famous war painting is A Battery Shelled. The art critic of The Daily Express argued: "Wyndham Lewis endeavours to show the war in terms of energy - Battery Shelled - in which the symbolism dominates, in which men lose their human form in action; chimneys wave and bend, and the very shells zigzag in lumps and masses across the sky."

The war changed Percy Wyndham Lewis' views on art as a result of his experiences in the First World War. He told a friend that Vorticism was only "a little narrow segment of time, on the far side of the war... you have to regard, as far as I am concerned, as a black solid mass, cutting off all that went before it". It has been argued that the "destructive power of a war dominated by terrible mechanical weapons altered Lewis's attitude towards the machine age."

Percy Wyndham Lewis began a relationship with Edith Sitwell. According to her biographer, Victoria Glendinning, "this is the only occasion on record when any man is alleged to have shown direct sexual interest in Edith". During this period he began painting a portrait of Sitwell. This was abandoned in 1923 when he decided to give up painting. Over the next few years he concentrated on writing The Man of the World, a book that was never published.

In 1927 he returned to painting and his most important painting during this period was Bagdad. A novel, The Apes of God, was published in 1930. This was followed by an admiring book on Adolf Hitler. His neo-fascist political views seriously damaged his reputation and just before the outbreak of the Second World War, Wyndham Lewis returned to Canada. He lived in Toronto before being appointed as a lecturer at Assumption College in Windsor.

Lewis moved back to London in 1945. The following year he became the art critic of The Listener. He held the post until losing his sight in 1951. With the help of friends he managed to publish the autobiographical Self-Condemned (1954) and The Human Age (1955).

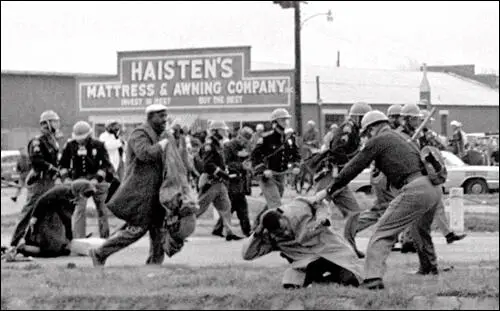

On this day in 1965 a Selma protest march is attacked by mounted police. After the murder of Jimmie Lee Jackson during the voter registration drive by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) it was decided to dramatize the need for a federal registration law. With the help of Martin Luther King and Ralph David Abernathy of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), leaders of the SCCC organised a protest march from Selma to the state capitol building in Montgomery, Alabama. The first march on 1st February, 1965, led to the arrest of 770 people. A second march, led by John Lewis and Hosea Williams, on 7th March, was attacked by mounted police. The sight of state troopers using nightsticks and tear gas was filmed by television cameras and the event became known as Bloody Sunday.

Martin Luther King led another march of 1,500 people two days later. After crossing the Pettus Bridge the marchers were faced by a barricade of state troopers. King disappointed many of his younger followers when he decided to turn back in order to avoid a confrontation with the troopers. Soon afterwards, one of white ministers on the march, James J. Reeb, was murdered.

President Lyndon B. Johnson now decided to take action and sent troops, marshals and FBI Agents to protect the protesters. On Thursday, 25th March, King led 25,000 people to the Alabama State Capitol and handed a petition to Governor George Wallace, demanding voting rights for African Americans. That night, the Ku Klux Klan killed Viola Liuzzo while returning from the march.

On 6th August, 1965, Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act. This removed the right of states to impose restrictions on who could vote in elections. Johnson explained how: "Every American citizen must have an equal right to vote. Yet the harsh fact is that in many places in this country men and women are kept from voting simply because they are Negroes." The legislation now empowered the national government to register those whom the states refused to put on the voting list.

On this day in 2002 pioneering journalist Shelley Mydans died in Sacramento, California,. Shelley Mydans, the daughter of a university professor, was born in Stanford, United States, in 1915. After college she moved to New York where she found work with as a journalist with the Literary Digest.

In 1936 she joined the staff of Life Magazine where she met the photographer Carl Mydans. In 1938 the couple married and the following year they were sent to Europe to cover the Second World War. At first they went to England before covering the war in Sweden, Finland, Portugal, Italy, China, and Hong Kong. During this period they travelled over 45,000 miles in pursuit of picture stories.

Shelley and her husband were in the Philippines when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor. Trapped in Manila they were captured by the Japanese Army and were interned with other Americans and remained in captivity until December 1943. Shelley wrote a novel, Open City, about her experiences in a Japanese prison camp.

When the US Army regained the Philippines in 1945 Carl Mydans flew to Manila. However, General Douglas MacArthur refused to allow women correspondents to cover the war and she had to go to Guam. She later recalled: "I was accredited to the navy, but I was not - because I was a woman - allowed to cover action on naval ships or planes and my articles had to be confined to such things as the navy flight nurses and marine base camps."

After the war Shelley worked for ABC network and wrote scripts for the March of Time radio series but resigned when her first child was born.

On this day in 2006 Gordon Parks died. Gordon Parks was born in Fort Scott, Kansas, on 30th November, 1912. Parks worked as a nightclub pianist and a railroad waiter, before taking up photography.

In 1937 Parks was invited by Roy Stryker to join the the federally sponsored Farm Security Administration. This small group of photographers, including Esther Bubley, Marjory Collins, Mary Post Wolcott, Arthur Rothstein, Walker Evans, Russell Lee, Jack Delano, Charlotte Brooks, John Vachon, Carl Mydans, Dorothea Lange and Ben Shahn, were employed to publicize the conditions of the rural poor in America. Parks also worked on the Standard Oil project before becoming a staff photographer with Life Magazine (1948-68).

Parks made his directorial debut with Flavio (1964). This was followed by The World of Piri Thomas(1968) and The Learning Tree (1969), an adaptation of his autobiographical novel about growing up in Kansas. Other films made by Parks include Shaft (1971), Shaft's Big Score (1972), The Super Cops (1973), Leadbelly (1976) and Solomon Northup's Odyssey (1984).

the Frederick Douglass housing project in June, 1942.