On this day on 5th November

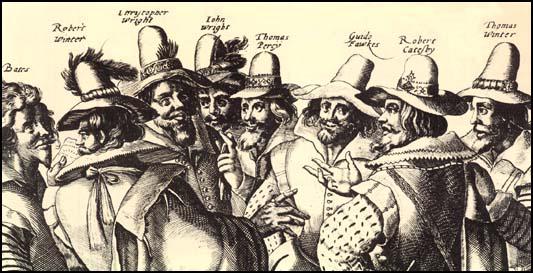

On this day in 1605 Robert Catesby, Thomas Wintour, Guy Fawkes, Thomas Percy, John Wright, Francis Tresham, Everard Digby, Robert Wintour, Thomas Bates and Christopher Wright planned to blow up Parliament.

Catesby's plan involved blowing up the Houses of Parliament on 5th November, 1605. This date was chosen because the king was due to open Parliament on that day. At first the group tried to tunnel under Parliament. This plan changed when Thomas Percy was able to hire a cellar under the House of Lords. The plotters then filled the cellar with barrels of gunpowder. The conspirators also hoped to kidnap the king's daughter, Elizabeth. In time, Catesby was going to arrange Elizabeth's marriage to a Catholic nobleman.

One of the people involved in the plot was Francis Tresham. He was worried that the explosion would kill his friend and brother-in-law, Lord Monteagle. On 26th October, Tresham sent Lord Monteagle a letter warning him not to attend Parliament on 5th November. Monteagle became suspicious and passed the letter to Robert Cecil. Cecil quickly organised a thorough search of the Houses of Parliament.

While searching the cellars below the House of Lords, Sir Thomas Knyvett, keeper of the Palace of Westminster, and his men found Guy Fawkes, who claimed he was John Johnson, the servant of Thomas Percy. He was arrested, and when his men hauled away the faggots and brushwood, they uncovered thirty-six barrels - nearly a ton - of gunpowder.

Guy Fawkes was tortured and admitted that he was part of a plot to "blow the Scotsman (James) back to Scotland". On the 7th November, after enduring further tortures, Fawkes gave the names of his fellow conspirators. "Catesby suggested... making a mine under the upper house of Parliament... because religion had been unjustly suppressed there... twenty barrels of gunpowder were moved to the cellar... It was agreed to seize Lady Elizabeth, the king's eldest daughter... and to proclaim her Queen".

The trial began on the 27th January, 1606. The Attorney-General Sir Edward Coke made a long speech, that included a denial that the King had ever made any promises to the Catholics. He then read out the confessions of the men accused of the crime. Thomas Wintour made a statement where he admitted his involvement but pleaded that his brother, Robert Wintour, should be spared. Everard Digby pleaded guilty, but justified his actions by claiming that the insisting that the King had reneged upon promises of toleration for Catholics.

On 30th January, Everard Digby, Robert Wintour, John Grant, and Thomas Bates, were tied to hurdles and dragged through the crowded streets of London to St Paul's Churchyard. Digby, the first to mount the scaffold, asked the spectators for forgiveness, and refused the attentions of a Protestant clergyman. He was stripped of his clothing, and wearing only a shirt, climbed the ladder to place his head through the noose. He was quickly cut down, and while still fully conscious was castrated, disembowelled, and then quartered, along with the three other prisoners.

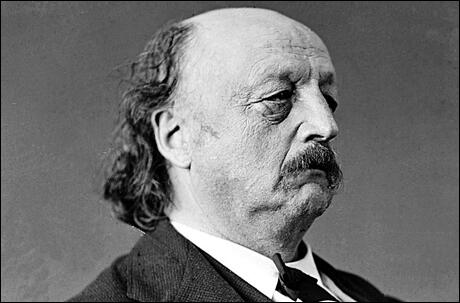

On this day in 1818 Benjamin Butler, American general was born. After graduating from Waterville College in 1838 he became a successful criminal lawyer in Lowell, Massachusetts. As a member of the Democratic Party, Butler served two terms in the state legislature, where he developed a reputation for being sympathetic to the plight of the poor.

Butler supported John Beckenridge against Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 presidential election but immediately gave his support to the Union on the outbreak of the American Civil War. Butler was a brigadier general in the Massachusetts militia and during the Fort Sumter crisis rushed his unit to protect Washington. On 13th May, 1861, Butler used his troops to capture Baltimore. Impressed by his loyalty and initiative, Abraham Lincoln promoted Butler to the rank of major general and sent him to command Fort Monroe in Virginia. Soon afterwards, runaway slaves began to appear at the fort seeking protection. The slaveowners demanded that the runaways should be returned. Butler refused, issuing a statement that he considered the slaves to be "contraband of war".

President Jefferson Davis accused Butler of "inciting African slaves to insurrection" in New Orleans by arming them for war. Davis issued a statement ordering that Butler "no longer be considered or treated simply as a public enemy of the Confederate States of America, but as an outlaw and common enemy of mankind, and that, in the event of his capture, the officer in command of the captured force do cause him to be immediately executed by hanging."

In November, 1863, Edwin M. Stanton, the Secretary of War, sent Butler to New York City with 5,000 troops. Stanton feared that during the presidential elections the city might see a return to the Draft Riots that had taken place that summer. The move was successful and the city remained securely under the control of the Union Army.

Abraham Lincoln decided he wanted Butler as his running mate in the 1864 presidential election. It was argued that this would help Lincoln win the votes of the War Democrats. Simon Cameron was sent to talk to Butler about joining the campaign. However, Butler rejected the offer, jokingly saying that he would only accept if Lincoln promised "that within three months after his inauguration he would die".

The American Civil War radicalized Butler. He became a strong opponent of slavery and refused to return fugitive slaves. He was also one of the few military commanders who favoured the recruitment of black regiments. He established a unit of African American soldiers called the First Regiment Louisiana Native Guards. In December, 1864, he united thirty-seven black regiments to form the Twenty-Fifth Corps. He also arranged for these soldiers to be taught to read and write. These actions made him very popular with the Radical Republicans in Congress.

In 1867 Butler joined with Benjamin Loan and James Ashley in claiming that Andrew Johnson had been involved in the conspiracy to murder Abraham Lincoln. Butler asked the question: "Who it was that could profit by assassination (of Lincoln) who could not profit by capture and abduction? He followed this with: "Who it was expected by the conspirators would succeed to Lincoln, if the knife made a vacancy?" He also implied that Johnson had been involved in tampering with the diary of John Wilkes Booth. "Who spoliated that book? Who suppressed that evidence?"

In November, 1867, the Judiciary Committee voted 5-4 that Andrew Johnson be impeached by high crimes and misdemeanors. The majority report written by Thomas Williams contained a series of charges including pardoning traitors, profiting from the illegal disposal of railroads in Tennessee, defying Congress, denying the right to reconstruct the South and attempts to prevent the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment.

On 30th March, 1868, Johnson's impeachment trial began. Johnson was the first and only president of the United States to be impeached. The trial, held in the Senate in March, was presided over by Chief Justice Salmon Chase. During the trial Butler was one of Johnson's fiercest critics.

Although a large number of senators believed that Johnson was guilty of the charges, they disliked the idea of Benjamin Wade becoming the next president. Wade, who believed in women's suffrage and trade union rights, was considered by many members of the Republican Party as being an extreme radical. James Garfield warned that Wade was "a man of violent passions, extreme opinions and narrow views who was surrounded by the worst and most violent elements in the Republican Party." Others Republicans such as James Grimes argued that Johnson had less than a year left in office and that they were willing to vote against impeachment if Johnson was willing to provide some guarantees that he would not continue to interfere with Reconstruction.

When the vote was taken all members of the Democratic Party voted against impeachment. So also did those Republicans such as Lyman Trumbull, William Fessenden and James Grimes, who did not want Wade to become president. The result was 35 to 19, one vote short of the required two-thirds majority for conviction. A further vote on 26th May, also failed to get the necessary majority needed to impeach Johnson. The Radical Republicans were angry that not all the Republican Party voted for a conviction and Butler claimed that Johnson had bribed two of the senators who switched their votes at the last moment.

On this day in 1857 Ida Tarbell, investigative journalist was born. Ida was an intelligent student and after leaving Allegheny College, Meadville, she found employment as a teacher at Poland Union Seminary in Poland, Ohio. Her main desire was to work as a writer and after two years teaching she began working for Theodore Flood, editor of The Chautauquan. Flood quickly realised her talent and in 1886 she was appointed managing editor. A job she did for the next eight years.

In 1891 Tarbell went to Paris and studied at Sorbonne University for three years. Her main areas of interest were the activities of Anne Louise Germaine de Staël-Holstein and Marie-Jeanne Roland, two women involved in the French Revolution. While in France she continued to contribute to American newspapers.

Samuel McClure, created McClure's Magazine, an American literary and political magazine, in June 1893. Selling at the low price of 15 cents, this illustrated magazine published the work of leading popular writers such as Rudyard Kipling, Robert Louis Stevenson and Arthur Conan Doyle. McClure also produced articles about historical figures from the past and commissioned Tarbell to write about Napoleon Bonaparte.

Lincoln Steffens, the editor of the magazine, was so impressed with her work, he recruited her as a staff writer. Tarbell's 20-part series on Abraham Lincoln doubled the magazine's circulation. In 1900 this material was published in a two-volume book, The Life of Abraham Lincoln. Steffens was interested in using McClure's Magazine to campaign against corruption in politics and business. This style of investigative journalism that became known as muckraking.

Tarbell's articles on John D. Rockefeller and how he had achieved a monopoly in refining, transporting and marketing oil appeared in the magazine between November, 1902 and October, 1904. This material was eventually published as a book, History of the Standard Oil Company (1904). Rockefeller responded to these attacks by describing Tarbell as "Miss Tarbarrel". The New York Times commented that "Miss Tarbell's fine analytical powers and gift for popular interpretation stood her in good stead" in the articles that she wrote for the magazine. It is claimed that these articles were partly responsible for the passing of the Clayton Antitrust Act.

In 1906 Tarbell joined with Lincoln Steffens, Ray Stannard Baker and William A. White to establish the radical American Magazine. Steffens's biographer, Justin Kaplan, the author of Lincoln Steffens: A Biography (1974), has argued: "That summer he and his partners celebrated their freedom from McClure's house of bondage, as they now saw it. There was a spirit of picnic and honeymoon about the enterprise; affections, loyalties, professional comradeship had never seemed quite so strong before and never would again. They dealt with each other as equals." Steffens later commented: "We were all to edit a writers' magazine." Articles by Tarbell for the magazine included John D. Rockefeller: A Character Sketch (July, 1907); Roosevelt vs. Rockefeller (December, 1908); The Mysteries and Cruelties of the Tariff (November, 1910) and The Hunt for the Money Trust (May, 1913). She also wrote several books on the role of women including The Business of Being a Woman (1912) and The Ways of Women (1915).

C. C. Regier, the author of The Era of the Muckrakers (1933) has argued that it is possible to tabulate the achievements of investigative journalism by Tarbell and her friends: "The list of reforms accomplished between 1900 and 1915 is an impressive one. The convict and peonage systems were destroyed in some states; prison reforms were undertaken; a federal pure food act was passed in 1906; child labour laws were adopted by many states; a federal employers' liability act was passed in 1906, and a second one in 1908, which was amended in 1910; forest reserves were set aside; the Newlands Act of 1902 made reclamation of millions of acres of land possible; a policy of the conservation of natural resources was followed; eight-hour laws for women were passed in some states; race-track gambling was prohibited; twenty states passed mothers' pension acts between 1908 and 1913; twenty-five states had workmen's compensation laws in 1915; an income tax amendment was added to the Constitution; the Standard Oil and the Tobacco companies were dissolved; Niagara Falls was saved from the greed of corporations; Alaska was saved from the Guggenheims and other capitalists; and better insurance laws and packing-house laws were placed on the statute books."

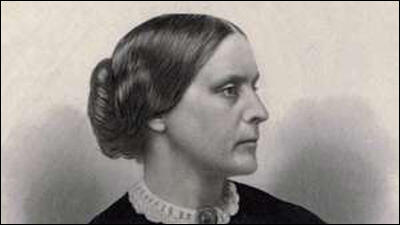

On this day in 1872 in defiance of the law, suffragist Susan B. Anthony votes for the first time, and is later fined $100. In 1869 Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton had formed the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). The organisation condemned the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments as blatant injustices to women. The NWSA also advocated easier divorce and an end to discrimination in employment and pay. Anthony toured the country making speeches on women's rights. In one year alone, she travelled 13,000 miles and made over 170 speeches. In 1872 Anthony attempted to vote in a an election in Rochester. She was arrested, charged and later found guilty of violating voting rights.

On this day in 1906 Priscilla McLaren died from pneumonia at home at Newington House, Blacket Avenue, Edinburgh, on 5th November 1906.

Priscilla Bright, the fifth in the family of eleven children of Jacob Bright (1775–1851) and his wife, Martha Wood Bright, was born in Rochdale on 8th September 1815. John Bright and Jacob Bright were two of her brothers.

Her father was a self-made and successful cotton manufacturer. He was deeply religious and sent his sons to Quaker schools. This education helped to develop in Bright a passionate commitment to political and religious equality.

Priscilla Bright was educated at Hannah Wilson's school in York, and at Hannah Johnson's school in Liverpool. Her "upbringing gave her a keen and active interest in politics which she never lost until the end of her life".

As a girl she visited Newgate prison with her fellow Quaker, Elizabeth Fry. After John Bright's first wife, Elizabeth, died in September 1841, leaving an eleven-year-old daughter, Priscilla Bright moved into her brother's Rochdale home. Like her brothers she was a strong supporter of the Liberal Party and eventually married, Duncan McLaren, who shared her progressive political beliefs. They had one daughter and two sons. She also took on responsibility for five stepchildren, the eldest of whom was seventeen.

Priscilla McLaren was a supporter of women's suffrage. On 20th May 1867, John Stuart Mill, proposed that women should be granted the same rights as men. "We talk of political revolutions, but we do not sufficiently attend to the fact that there has taken place around us a silent domestic revolution: women and men are, for the first time in history, really each other's companions... when men and women are really companions, if women are frivolous men will be frivolous... the two sexes must rise or sink together."

The 1867 Reform Act gave the vote to every male adult householder living in a borough constituency. Male lodgers paying £10 for unfurnished rooms were also granted the vote. This gave the vote to about 1,500,000 men. The Reform Act also dealt with constituencies and boroughs with less than 10,000 inhabitants lost one of their MPs. The forty-five seats left available were distributed by: (i) giving fifteen to towns which had never had an MP; (ii) giving one extra seat to some larger towns - Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham and Leeds; (iii) creating a seat for the University of London; (iv) giving twenty-five seats to counties whose population had increased since 1832.

Members of the Kensington Society were very disappointed when they heard the news and they decided to form the London Society for Women's Suffrage. Members included Barbara Bodichon, Jessie Boucherett, Emily Davies, Francis Mary Buss, Dorothea Beale, Anne Clough, Millicent Garrett Fawcett, Helen Taylor and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson. Priscilla McLaren decided to form the Edinburgh Society for Women's Suffrage.

In 1870 Priscilla McLaren joined with her sister-in-law, Ursula Bright, Josephine Butler and Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy in forming the Ladies' National Association, an organisation that pressed for the repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts. This legislation allowed policeman to arrest prostitutes in ports and army towns and bring them in to have compulsory checks for venereal disease. If the women were suffering from sexually transmitted diseases they were placed in a locked hospital until cured. It was claimed that this was the best way to protect men from infected women. Many of the women arrested were not prostitutes but they still were forced to go to the police station to undergo a humiliating medical examination.

In 1870 her brother, Jacob Bright and Sir Charles Wentworth Dilke introduced what was the first women's suffrage bill. In one speech he argued: "I know of no reason for the electoral disabilities of women. I know some reasons, which if there are to be electoral disabilities, would lead me to begin elsewhere than with women. Women are less criminal than men: they are more temperate than men the distinction is not small, it is broad and conspicuous; women are less vicious in their habits than men; they are more thrifty, more provident: they give more to the family, and take less to themselves."

After its defeat Jacob Bright introduced another Women's Suffrage Bill in 1871. Once again, William Gladstone, the leader of the Liberal Party, arranged for it to be defeated and commented that women voting in elections would be "a practical evil of an intolerable character".

Priscilla McLaren was active in the demands for changes in the law on women's ownership of property. She became increasingly frustrated with male politicians. She told a conference of the Married Women's Property Committee in 1880 that their struggle was "a question of power... they (men) could not bear that the wife should have power".

The Married Women's Property Act was eventually passed in 1882. Under the terms of the act married women had the same rights over their property as unmarried women. This act therefore allowed a married woman to retain ownership of property which she might have received as a gift from a parent. Before the 1882 Married Women's Property Act was passed this property would have automatically have become the property of the husband.

On this day in 1913 Vivien Leigh, Indian-British actress was born. Leigh won the Academy Award for Best Actress twice, for her performances as Scarlett O'Hara in Gone with the Wind (1939) and Blanche DuBois in the film version of A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), a role she had also played on stage in London's West End in 1949. She also won a Tony Award for her work in the Broadway musical version of Tovarich (1963). Although her career had periods of inactivity, in 1999 the American Film Institute ranked Leigh as the 16th greatest female movie star of classic Hollywood cinema.

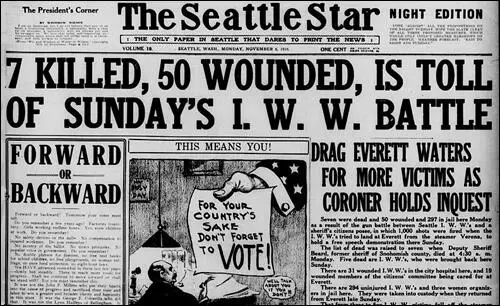

On this day in 1916 there was armed confrontation between the police and members of the Industrial Workers of the World at Everett, Washington. The IWW (also called Wobblies) had arrived in town to give support for striking shingle workers who had been involved in a five-month dispute. Once there, vigilantes employed by businessmen had beaten them up with axe handles and run them out of town.

On the 5th November about 300 IWW members met at the IWW Hall in Seattle and then marched down to the docks where they boarded the steamers Verona and Calista which then headed north to Everett. More than 200 vigilantes (citizen deputies) under the authority of Sheriff Donald McRae, met the ships when they sailed into the dock. McRae drew his pistol, told them he was the sheriff, he was enforcing the law, and they couldn't land. The vigilantes then opened fire on the IWW. Passengers aboard the Verona rushed to the opposite side of the ship, nearly capsizing the vessel. The ship's rail broke and a number of passengers were ejected into the water, some drowned as a result but how many is not known, or whether persons who'd been shot also went overboard. Over 175 bullets pierced the pilot house alone.

Two citizen deputies were killed with about 18 others wounded, including Sheriff McRae. The two deputies that were shot were actually shot in the back by fellow deputies; their injuries were not caused by IWW gunfire. It is estimated that about 12 members of the IWW officially were killed.

Seventy-four Wobblies were arrested as a direct result of the Everett Massacre including IWW leader Thomas H. Tracy. They were charged with the murder of the two deputies. After a two-month trial, Tracy was acquitted by a jury on May 5, 1917. Shortly thereafter, all charges were dropped against the remaining 73 defendants and they were released from jail.

On this day in 1925 Sidney Reilly is executed by the secret police of the Soviet Union. In April 1918, Mansfield Smith-Cumming, the head of MI6 sent Reilly to Russia. He joined a team that included the Robert Bruce Lockhart, the Head of Special Mission to the Soviet Government with the rank of acting British Consul-General, George Alexander Hill, Paul Dukes, Cudbert Thornhill, Ernest Boyce, Oswald Rayner and Stephen Alley. Xenophon Kalamatiano, the main American agent in Russia, also joined this conspiracy. The main objective of this group was to bring about the overthrow of the Bolshevik government. Reilly had a passionate hatred for communism. "Bolshevism had been baptised in the blood of the bourgeoise... its leaders were criminals, assassins, murderers, gunmen, desperadoes.... Over all, silent, secret, ferocious, menacing, hung the crimson shadow of the Cheka. The new masters were ruling in Russia."

Jan Buikis, a Soviet agent, made contact with Francis Cromie, the naval attaché at the British Embassy, and requested a meeting with Robert Bruce Lockhart. On 14th August, 1918, Buikis and Colonel Eduard Berzin, met Lockhart. Berzin told Lockhart that there was serious disaffection among the Lettish troops and asked for money to finance an anti-Bolshevik coup. Lockhart, who described Berzin as "a tall powerfully-built man with clear-cut features and hard steely eyes" was impressed by Berzen. He told Lockhart that he was a senior commander of the Lettish (Latvian) regiments that had been protecting the Bolshevik Government ever since the revolution. Berzin insisted that these regiments had proved indispensable to Lenin, saving his regime from several attempted coups d'état.

Robert Bruce Lockhart asked Xenophon Kalamatiano to help arrange funds from America to pay for the overthrow of the Bolsheviks. Colonel Henri de Vertement, the leading French intelligence agent in Russia also contributed money for the venture. Over the next week, George Reilly, Ernest Boyce and George Alexander Hill had regular meetings with Colonel Eduard Berzin, where they planned the overthrow of the Bolsheviks. During this period they handed over 1,200,000 rubles. Unknown to MI6 this money was immediately handed over to Felix Dzerzhinsky, the head of Cheka. So also were the details of the British conspiracy.

Berzin told the agents that his troops had been to assigned to guard the theatre where the Soviet Central Executive Committee was to met. A plan was devised to arrest Lenin and Leon Trotsky at the meeting was to take place on 28th August, 1918. Robin Bruce Lockhart, the author of Reilly: Ace of Spies (1992) has argued: "Reilly's grand plan was to arrest all the Red leaders in one swoop on August 28th when a meeting of the Soviet Central Executive Committee was due to be held. Rather than execute them, Reilly intended to de-bag the Bolshevik hierarchy and with Lenin and Trotsky in front, to march them through the streets of Moscow bereft of trousers and underpants, shirt-tails flying in the breeze. They would then be imprisoned. Reilly maintained that it was better to destroy their power by ridicule than to make martyrs of the Bolshevik leaders by shooting them." Reilly's plan was eventually rejected and it was decided to execute the entire leadership of the Bolshevik Party.

Reilly later recalled: "At a given signal, the soldiers were to close the doors and cover all the people in the Theatre with their rifles, while a selected detachment was to secure the persons of Lenin and Trotsky... In case there was any hitch in the proceedings, in case the Soviets showed fight or the Letts proved nervous... the other conspirators and myself would carry grenades in our place of concealment behind the curtains." However, at the last moment, the Soviet Central Executive Committee meeting was postponed until 6th September.

On 31st August 1918 Dora Kaplan attempted to assassinate Lenin. It was claimed that this was part of the British conspiracy to overthrow the Bolshevik government and orders were issued by Felix Dzerzhinsky, the head of Cheka, to round up the agents based in British Embassy in Petrograd. The naval attaché, Francis Cromie was killed resisting arrest. According to Robin Bruce Lockhart: "The gallant Cromie had resisted to the last; with a Browning in each hand he had killed a commissar and wounded several Cheka thugs, before falling himself riddled with Red bullets. Kicked and trampled on, his body was thrown out of the second floor window."

Ernest Boyce and Robert Bruce Lockhart were both arrested but Sidney Reilly had a lucky escape. He arranged to meet Cromie that morning. He arrived at the British Embassy soon after Cromie had been killed: "The Embassy door had been battered off its hinges. The Embassy flag had been torn down. The Embassy had been carried by storm." Reilly now went into hiding and after paying 60,000 rubles to be smuggled out of Russia on board a Dutch freighter.

Reilly arrived back in London with another agent, George Alexander Hill, were asked to return to London in November 1918. Mansfield Smith-Cumming, the head of MI6 was very pleased with the information the two men had smuggled out of Russia and arranged for them to receive the Military Cross. Smith-Cumming then asked the men if they were willing to return to Russia. The main objective was to assess the prospects of the White Army led by General Anton Denikin against the Red Army in the Russian Civil War. The men agreeed but was shocked when they were told that their train bound for Odessa was departing in two hours. Hill and Reilly realised that it was a dangerous mission and if they were caught by the Bolsheviks they would be executed.

Reilly wrote to Robert Bruce Lockhart: "I told "C" (and I am anxious that you should know it too) that I consider that there is a very earnest obligation upon me to continue to serve - if my services can be made use of in the question of Russia and Bolshevism. I feel that I have no right to go back to the making of dollars until I have discharged my obligations. I also venture to think that the state should not lose my services. I would devote the rest of my wicked life to this kind of work.... I need not enlarge upon my motives to you; I am sure you will understand them and if you can do something I should feel grateful. I should like nothing better than to serve under you. I don't believe that the Russians can do anything against the Bolsheviks without our most active support. The salvation of Russia has become a most sacred duty which we owe to the untold thousands of Russian men and women who have sacrificed their lives because they trusted in the promise of our support."

Ernest Boyce, the MI6 station chief in Helsinki, wrote to Reilly asking him to meet the leaders of Monarchist Union of Central Russia in Moscow. Reilly replied: "Much as I am concerned about my own personal affairs which, as you know, are in a hellish state. I am, at any moment, if I see the right people and prospects of real action, prepared to chuck everything else and devote myself entirely to the Syndicate's interests. I was fifty-one yesterday and I want to do something worthwhile, while I can."

According to Keith Jeffery, the author of MI6: The History of the Secret Intelligence Service (2010), Boyce had sent Reilly into Russia without clearing the scheme with his superiors in London. "Boyce had to take some of the blame for the tragedy. Back in London, as recalled by Harry Carr, his assistant in Helsinki" he was "carpeted by the Chief for the role he had played in this unfortunate affair."

After a number of delays caused mainly by Reilly's debt-ridden business dealings, he met Ernest Boyce in Paris before crossing the Finnish border on 25th September 1925. At a house outside Moscow two days later he had a meeting with the leaders of MUCR, where he was arrested by the secret police. Reilly was told he would be executed because of his attempts to overthrow the Bolshevik government in 1918.

According to the Soviet account of his interrogation, on 13th October 1925, Reilly wrote to Felix Dzerzhinsky, head of Cheka, saying he was ready to cooperate and give full information on the British and American Intelligence Services. Sidney Reilly's appeal failed and he was executed on 5th November 1925. For his role in the "liquidation" of Savinkov and Reilly, Artur Artuzov was awarded the Order of the Red Banner.

On this day in 1959 Gladice Keevil, aged 75, at St Thomas Hospital, Lambeth, London. She left effects valued at £19,970. 6s 7d.

Gladice Keevil, he youngest of six children born to Georgina Mary Moon (1852–1947) and William Richard Keevil (1853–1929), was born in 1884. Her father was a "Farmer & Dairyman" of Clutterhouse Farm, Cricklewood, Middlesex. At the time of the 1891 Census, the family had a female domestic servant living at the farm.

After being educated at the Frances Mary Buss School in Camden and at Lambeth Art School she worked as a governess for 18 months in France and the United States. On her return to England in 1907 she joined the Women's Social and Political Union.

Keevil worked closely with Emma Sproson who was a member of the Wolverhampton Independent Labour Party. In April 1907 the two women arranged for Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence to join them in a series of Market place meetings. Keevil also recruited Hilda Burkitt as a paid organiser in Birmingham. "Hilda held regular evening meetings in parks and on street corners to bring the movement to attention of residents on their way home from work."

In February 1908 she was one of those arrested with Emmeline Pankhurst in taking part in a demonstration outside the House of Commons. Keevil was found guilty and spent six weeks in Holloway Prison. On her release she was appointed National Organiser in the Midlands and established a regional office in Birmingham. Later she was joined by Ada Flatman.

Gladice Keevil also spoke at Hyde Park meeting on 21st June 1908. The Daily News reported that: "Miss Keevil was a particularly striking figure. Robed in flowing white muslin, her lithe figure swayed to every changing expression, and the animated face that smiled and scolded by turns beneath the black straw hat and waving white ostrich feather, was the centre of one of the densest crowds."

Colonel Linley Blathwayt was sympathetic to the WSPU cause and he built a summer-house in the grounds of the estate that was called the "Suffragette Rest". Members of the WSPU who endured hunger strikes went to stay at Eagle House and the summer-house. Colonel Blathwayt decided to create a suffragette arboretum in a field adjacent to the house. The idea was for women to be invited to plant a tree to commemorate their prison sentences and hunger strikes.

Mary Blathwayt recorded Gladice Keevil's visit in May 1908. "Miss Keevil came over from Market Drayton ... She and I held an open air meeting at the Wharf. I took the chair, the first time I have ever done such a thing. I read out a few words of introduction, announced a meeting for tomorrow and called upon Miss Keevil to speak."

The WSPU organised a mass meeting to take place on 21 June 1908 called Women's Sunday at Hyde Park. The leadership intended it "would out-rival any of the great franchise demonstrations held by the men" in the 19th century. Sunday was chosen so that as many working women as possible could attend. It is claimed that it attracted a crowd of over 300,000. At the time, it was the largest protest to ever have taken place in Britain. Speakers included Gladice Keevil, Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst, Adela Pankhurst, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Mary Gawthorpe, Jennie Baines, Rachel Barrett, Marie Brackenbury, Georgina Brackenbury, Annie Kenney, Nellie Martel, Marie Naylor, Flora Drummond and Edith New.

Gladice Keevil became a popular speaker at WSPU meetings all over the country. B. M. Willmott Dobbie pointed out that she was "noted for her good looks." This included a meeting in Leeds on 26th July 1908, which included speeches from Emmeline Pankhurst, Annie Kenney, Mary Gawthorpe, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Jennie Baines, Adela Pankhurst, and Flora Drummond. The local newspaper reported: "Miss Gladys Keevil, a young lady with a winning smile and a most becoming hat, exerted a distinct influence upon her hearers. She admitted that some of the doings of the Suffragettes had not been quite lady-like, but she pleaded that they had done nothing unwomanly."

On 22nd September 1909 Mary Leigh, Charlotte Marsh, Laura Ainsworth, Mabel Capper, Patricia Woodcock, Hilda Burkitt and Rona Robinson conducted a rooftop protest at Bingley Hall, Birmingham, where Herbert Asquith was addressing a meeting from which all women had been excluded. Using an axe, Leigh removed slates from the roof and threw them at the police below. Sylvia Pankhurst later recalled: "No sooner was this effected, however, than the rattling of missiles was heard on the other side of the hall, and on the roof of the house, thirty feet above the street, lit up by a tall electric standard was seen the little agile figure of Mary Leigh, with a tall fair girl (Charlotte Marsh) beside her. Both of them were tearing up the slates with axes, and flinging them onto the roof of the Bingley Hall and down into the road below-always, however, taking care to hit no one and sounding a warning before throwing. The police cried to them to stop and angry stewards came rushing out of the hall to second this demand, but the women calmly went on with their work."

The Freeman's Journal reported: "Mary Leigh and Mabel Capper have long been among the most reckless members of the suffragist movement. They were two of a large band who visited Birmingham in September, 1909, and were arrested with others on charge arising out of a desperate and well-organised attempt to storm Bingley Hall where Mr Asquith was speaking to an audience of ten thousand. Leigh and another, eluding the vigilance of the police, climbed on to the roof of an adjoining factory, from which she threw ginger beer bottles, slates, and other missiles on the glass roof of Bingley Hall, and into the street when the Premier was passing in a motor car. While awaiting his appearance the women amused themselves by throwing projectiles at the crowd in the street and the police, several officers being struck. A policeman who climbed on the roof - a hazardous undertaking - found Leigh with her boots off, jumping about like a cat, as he described it, and armed with an axe used for the purpose of ripping slates from the roof: 'Come on up at your peril,' the women shouted to the officers, who were struck several times before effecting an arrest."

At a meeting in Birmingham that evening Gladice Keevil pointed out that the WSPU felt "very grateful to the few men who were courageous enough to protest where Mr Asquith was speaking on the Budget". However, it was vitally important that women influenced government policy: "What was wanted was the women's point of view. It was the housekeeping women who know how to make a pound go as far as a man would take 25s so really the Budget was a great argument in their favour." She added "that the Suffragists were determined that... women were going to take their share of the work of building up the nation."

Hilda Burkitt like the other women arrested at the rooftop protest at Bingley Hall, Birmingham, immediately decided to go on hunger-strike, a strategy developed by Marion Wallace-Dunlop a few weeks earlier. Wallace-Dunlop had been immediately released when she had tried this in Holloway Prison, but the governor of Winson Green Prison, was willing to feed the women by force.

On the 20th September, 1909, Hilda declared in an official petition to the Home Office that until her political status was acknowledged, she would "refuse to take any Prison Food, & as far as is in my power I shall break all prison rules". She demanded that the Home Office "reply to my Petition at once, as if I should die through my fasting, my death will lie at your door." Hilda pointed out that she was "ready to lay down my life, to bring about the Freedom of my Sex."

Hilda refused to eat any food. "Hilda was examined in the morning by the prison doctor and one sent especially by the Home Office. That afternoon, she was taken to the prison kitchen, where four wardresses, a matron and two doctors attempted and eventually succeeded in restraining her to a chair with a blanket. Hilda shouted 'I will not take food! I refuse! I will not swallow!' and continued to resist attempts to feed her from a cup. In response, the prison doctor declared that ‘illegal or not, I'm going to use it' and proceeded to attempt feeding by nasal tube. Hilda continued to resist and coughed the tube out twice.... The doctors then gagged her and used a stomach tube to feed her through her mouth. Afterwards, Hilda repeated what she had said to the wardresses - 'I'm broken, but not beaten'. These experiences were repeated throughout her month in Winson Green as she undertook three hunger strikes, lasting 86, 91 and 24 hours respectively. Suffering great pain, she only managed sleep for four nights out of the entire month."

Gladice Keevil visited Hilda Burkitt in prison and the Nursing Home where she was taken after her release. She also complained about the way Mary Leigh had been treated in prison: "Miss Keevil also spoke on Friday at the weekly meeting in the Bull Ring, when, in spite of threatening weather, there was a good crowd, and many more questions were asked. Great indignation is felt at the continued imprisonment of Mrs Leigh while other women of more influential position have been released."

In July 1910, Gladice Keevil addressed several meetings in Northern Ireland. This included one speech at the Ulster Minor Hall: "Miss Keevil, who was cordially welcomed explained that they (WSPU) made their claim for the vote not on the grounds of sentiment but on the ground of simple justice. Women were considered adult enough to pay taxes, but not to vote." One member of the audience commented that she was a "clever speaker and knows her subject".

Keevil was a regular visitor to Eagle House near Batheaston. Her host, Emily Blathwayt, described her as "a very nice girl... she seems interested in all subjects and enjoyed everything here... one of the nicer Suffragettes". On 4th November 1910 Colonel Linley Blathwayt planted a tree, a Picea Pungens Kosteriana, in her honour in his suffragette arboretum in a field adjacent to the house.

Gladice Keevil was still active in the WSPU on 28th November, 1912. This came to an end when she married Leslie Rickford, a 25-year-old bank clerk. She gave birth to three children: Lionel (born 1st June, 1914, Barnet, Middlesex - died 23rd May,1997, Worthing, West Sussex), Richard (born 1st June, 1914, Barnet, Middlesex – died 16th March,1990, Dartmouth, Devon) and Cecil (born 1917, Barnet, Hertfordshire - died 8th July 1964 at Warne House, Burpham, near Arundel, West Sussex).

After their marriage the family lived at 180 Willifield Way, Hendon. Between 1925 and 1946 Gladice Rickford made several journeys to India and Pakistan. It appears that by the 1920s, Gladice's husband, Leslie Rickford was a banker based in Bombay, India. After the Second World War he was a bank manager in England and the couple lived at 10 Houndean Rise, Lewes, Sussex.

After her husband's death in 1956 Gladice Rickford moved to the Wall Cottage, Burpham, near Arundel, West Sussex.

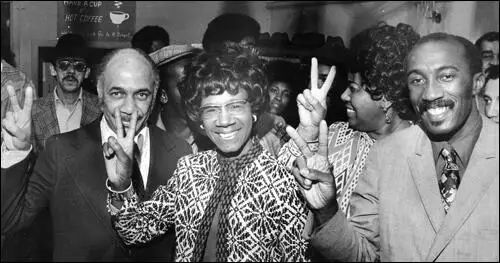

On this day in 1968 Shirley Chisholm became the first African American woman elected to Congress. She served for seven terms until 1983. In the 1972 United States presidential election she became the first black candidate to run for a major party's nomination for President of the United States, and the first woman to run for the Democratic Party 's presidential nomination.