On this day on 24th October

On this day in 1537 Jane Seymour, English queen died. Henry VIII married Jane on 30th May 1536. Coming as it did after the death of Catherine of Aragon and the execution of Anne Boleyn, there could be no doubt of the lawfulness of Henry's marriage to Jane. The new queen was introduced at court in June. "No coronation followed the wedding, and plans for an autumn coronation were laid aside because of an outbreak of plague at Westminster; Jane's pregnancy undoubtedly eliminated any possibility of a later coronation."

Jane Seymour gave birth to a boy on 12th October 1537 after a difficult labour that lasted two days and three nights. The child was named Edward, after his great-grandfather and because it was the eve of the Feast of St Edward. It was said that the King wept as he took the baby son in his arms. At the age of forty-six, he had achieved his dream. "God had spoken and blessed this marriage with an heir male, nearly thirty years after he had first embarked on matrimony."

On this day in 1561 Anthony Babington was born. In March 1586, Anthony Babington and six friends gathered in The Plough, an inn outside Temple Bar, where they discussed the possibility of freeing Mary, assassinating Elizabeth, and inciting a rebellion supported by an invasion from abroad. With his spy network, it was not long before Walsingham discovered the existence of the Babington Plot. To make sure he obtained a conviction he arranged for Gifford to visit Babington on 6th July. Gifford told Babington that he had heard about the plot from Thomas Morgan in France and was willing to arrange for him to send messages to Mary via his brewer friend.

However, Babington did not fully trust Gifford and enciphered his letter. Babington used a very complex cipher that consisted of 23 symbols that were to be substituted for the letters of the alphabet (excluding j. v and w), along with 35 symbols representing words or phrases. In addition, there were four nulls and a sybol which signified that the next symbol represents a double letter. It would seem that the French Embassy had already arranged for Mary to receive a copy of the necessary codebook.

Gilbert Gifford took the sealed letter to Francis Walsingham. He employed counterfeiters, who would then break the seal on the letter, make a copy, and then reseal the original letter with an identical stamp before handing it back to Gifford. The apparently untouched letter could then be delivered to Mary or her correspondents, who remained oblivious to what was going on.

The copy was then taken to Thomas Phelippes. Cryptanalysts like Phelippes used several methods to break a code like the one used by Babington. For example, the commonest letter in English is "e". He established the frequency of each character, and tentatively proposed values for those that appeared most often. Eventually he was able to break the code used by Babington. The message clearly proposed the assassination of Elizabeth.

Francis Walsingham now had the information needed to arrest Babington. However, his main target was Mary Stuart and he therefore allowed the conspiracy to continue. On 17th July she replied to Babington. The message was passed to Phelippes. As he had already broken the code he had little difficulty in translating the message that gave her approval to the assassination of Elizabeth. Mary Queen of Scots wrote: "When all is ready, the six gentlemen must be set to work, and you will provide that on their design being accomplished, I may be myself rescued from this place."

Walsingham had enough evidence to arrest Mary and Babington. However, to destroy the conspiracy completely, he needed the names of all those involved. He ordered Phelippes to forge a postscript to Mary's letter, which would entice Babington to name the other men involved in the plot. "I would be glad to know the names and qualities of the six gentleman which are to accomplish the designment; for it may be that I shall be able, upon knowledge of the parties, to give you some further advice necessary to be followed therein, as also from time to time particularly how you proceed."

Simon Singh, the author of The Code Book: The Secret History of Codes & Code-Breaking (2000) has pointed out: "The cipher of Mary Queen of Scots clearly demonstrates that a weak encryption can be worse than no encryption at all. Both Mary and Babington wrote explicitly about their intentions because they believed that their communications were secure, whereas if they had been communicating openly they would have referred to their plan in a more discreet manner. Furthermore, their faith in their cipher made them particularly vulnerable to accepting Phelippes's forgery. Sender and receiver often have such confidence in the strength of their cipher that they consider it impossible for the enemy to mimic the cipher and insert forged text. The correct use of a strong cipher is a clear boon to sender and receiver, but the misuse of a weak cipher can generate a very false sense of security."

Walsingham allowed the letters to continue to be sent because he wanted to discover who else was involved in this plot to overthrow Elizabeth. Eventually, on 25th June 1586, Mary wrote a letter to Anthony Babington. In his reply, Babington told Mary that he and a group of six friends were planning to murder Elizabeth. Babington discovered that Walsingham was aware of the plot and went into hiding. He hid with some companions in St John's Wood, but was eventually caught at the house of the Jerome Bellamy family in Harrow. On hearing the news of his arrest the government of the city put on a show of public loyalty, witnessing "her public joy by ringing of bells, making of bonfires, and singing of psalms".

Babington home was searched for documents that would provide evidence against him. When interviewed, Babington, who was not tortured, made a confession in which he admitted that Mary had written a letter supporting the plot. At his trial, Babington and his twelve confederates were found guilty and sentenced to hanging and quartering. "The horrors of semi-strangulation and of being split open alive for the heart and intestines to be wrenched out were regarded, like those of being burned to death, as awful but in the accepted order of things."

Gallows were set up near St Giles-in-the-Field and the first seven conspirators, led by Babington, were executed on 20th September 1586. Babington's last words were “Spare me Lord Jesus”. Another conspirator, Chidiock Tichborne, made a long speech where he blamed Babington "for drawing him in". The men "were hanged only for a short time, cut down while they were still alive, and then castrated and disembowelled".

The other seven were brought to the scaffold the next day and suffered the same death, "but, more favourably, by the Queens commandment, who detested the former cruelty". They hung until they were dead and only then suffered the barbarity of castration and disembowelling. The last to suffer was Jerome Bellamy, who was found guilty of hiding Babington and the others at his family's house in Harrow. His brother cheated the hangman by killing himself in prison.

On this day in 1857 Sheffield Football Club is founded in England. Football was a very popular sport in Sheffield and in 1857 a group of men established the club at Bramall Lane. It is believed to be the first football club in the world. Two former Harrow students, Nathaniel Creswick and William Prest, published their own set of rules for football. These new rules allowed for more physical contact than those established by some of the public schools. Players were allowed to push opponents off the ball with their hands. It was also within the rules to shoulder charge players, with or without the ball. If a goalkeeper caught the ball, he could be barged over the line. At first the Sheffield Club played friendly games against teams in London and Nottingham.

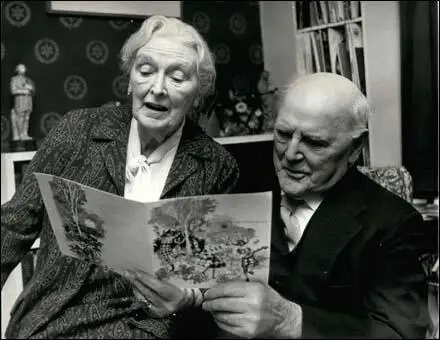

On this day in 1882 Sybil Thorndike, English actress is born She trained as a pianist but decided on theatre and in 1904 appeared in The Merry Wives of Windsor. She married Lewis Casson on 22nd December, 1908. After spending four years touring the United States with a Shakespearean Repertory Company she returned to England and became a leading figure in Annie Horniman's Repertory Company in Manchester. She also worked at the Old Vic (1914-19). Thorndike established herself as Britain's leading actress in Saint Joan (1924) by George Bernard Shaw.

Thorndike took a keen interest in politics and was a supporter of the Popular Front government in Spain during the Spanish Civil War. She joined with Emma Goldman, Rebecca West, Fenner Brockway and C. E. M. Joad to establish the Committee to Aid Homeless Spanish Women and Children.

On this day in 1906 several members of the Women's Social and Political Union including Emmeline Pethick Lawrence, Annie Kenney, Mary Gawthorpe, Dora Montefiore, Teresa Billington-Greig, Edith How-Martyn, Adela Pankhurst and Minnie Baldock are sent to prison for "using threatening and abuse words and behaviour with intent to provoke a breach of the peace."

On this day in 1906 Sylvia Pankhurst is sentenced to fourteen days in prison for making a disturbance in court.

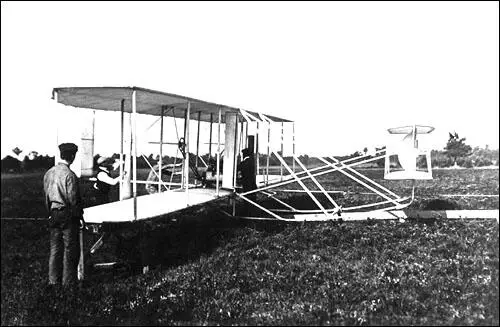

On this day in 1911 Orville Wright remains in the air nine minutes and 45 seconds in a glider at Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina. In 1908 Orville and Wilbur Wright produced the Wright Model A. This was a two-seater with an improved control system. It had a much more powerful engine and could reach a speed of 44 mph (71 kpm). However, on 17th September, the brothers had their first plane crash. Orville Wright was seriously injured and his passenger, Thomas Selfridge, was killed.

Wilbur took the machine to France and at a demonstration at the military field at Camp d'Auvours, set an endurance record of 2 hours 20 minutes 23 seconds. It also set an altitude record of 362 feet (110 m). As a result of the tests the brothers were able to sell construction licences for the Wright Model A to Britain, France and Germany. After the death of Wilbur Wright from typhoid fever in 1912, Orville lost interest in aviation and sold the Wright Company in 1915.

On this day in 1925 Jack Leslie was chosen to play for England against Ireland. However, the invitation to play for his country was withdrawn at the last moment. Leslie told the journalist, Brian Woolnough: "They must have forgot I was a coloured boy."

John (Jack) Leslie was born in Canning Town, London, on 17th August, 1901. He played for local team, Barking Town, before joining Plymouth Argyle in 1921. Leslie played at centre-forward and over the next thirteen years he scored 131 goals in 383 games.

Leslie was one of the first non-white players to play professional football. Others included Arthur Wharton, Walter Tull, Fred Corbett and Hassan Hegazi.

Leslie retired from professional football in 1934. He later worked as a member of the backroom staff of his local club, West Ham United .

Jack Leslie died on 25th November 1988.

On this day in 1929 Black Thursday on the New York Stock Exchange. Prices fell dramatically as sellers tried to find people willing to buy their shares. That evening, five of the country's bankers, led by Charles Edward Mitchell, chairman of the National City Bank, issued a statement saying that due to the heavy selling of shares, many were now under-priced. This statement failed to halt the reduction in demand for shares.

The New York Times reported: "The most disastrous decline in the biggest and broadest stock market of history rocked the financial district yesterday.... It carried down with it speculators, big and little, in every part of the country, wiping out thousands of accounts. It is probable that if the stockholders of the country's foremost corporations had not been calmed by the attitude of leading bankers and the subsequent rally, the business of the country would have been seriously affected. Doubtless business will feel the effects of the drastic stock shake-out, and this is expected to hit the luxuries most severely."

On the opening of the Wall Street Stock Exchange on 29th October, 1929, John D. Rockefeller, the American oil industry business magnate and successful industrialist, issued a statement which attempted to regain confidence in the state of the economy: "Believing that fundamental conditions of the country are sound and that there is nothing in the business situation to warrant the destruction of values that has taken place on the exchanges during the past week, my son and I have for some days been purchasing sound common stocks."

This did not have the desired impact on the market for that day over 16 million shares were sold. The market had lost 47 per cent of its value in twenty-six days. "Efforts to estimate yesterday's market losses in dollars are futile because of the vast number of securities quoted over the counter and on out-of-town exchanges on which no calculations are possible. However, it was estimated that 880 issues, on the New York Stock Exchange, lost between $8,000,000,000 and $9,000,000,000 yesterday. Added to that loss is to be reckoned the depreciation on issues on the Curb Market, in the over the counter market and on other exchanges."

Although less than one per cent of the American people actually possessed stocks and shares, the Wall Street Crash was to have a tremendous impact on the whole population. The fall in share prices made it difficult for entrepreneurs to raise the money needed to run their companies. Frederick Lewis Allen pointed out: "Billions of dollars' of profits - and paper profits - had disappeared. The grocer, the window-cleaner, and the seamstress had lost their capital. In every town there were families which had suddenly dropped from showy affluence into debt. Investors who had dreamed of retiring to live on their fortunes now found themselves back once more at the very beginning of the long road to riches. Day by day the newspapers printed the grim reports of suicides."

Within a short time, 100,000 American companies were forced to close and consequently many workers became unemployed. As there was no national system of unemployment benefit, the purchasing power of the American people fell dramatically. This in turn led to even more unemployment. Yip Harburg pointed out that before the Wall Street Crash, the American citizen thought: "We were the prosperous nation, and nothing could stop us now.... There was a feeling of continuity. If you made it, it was there forever. Suddenly the big dream exploded. The impact was unbelievable."

On this day in 1947 Susan Lawrence, who never married, died at her home, 28 Bramham Gardens, South Kensington and was cremated at Golders Green. On her death The Times obituarist wrote: "Tall and gaunt of figure in her later years, with rather close-cropped grey hair, piercing eyes, and an engaging habit of darting a finger at one in conversation, speaking in a rather sibilant, husky voice, she was the most transparently honest and unegotistical of politically minded women."

Susan Lawrence, the daughter of Nathaniel Lawrence, a wealthy solicitor, and Laura Bacon, was born in London on 12th August 1871. After being educated at University College and Newnham College, she worked as a school manager. In 1900 she was elected to the London School Board and four years later, was co-opted to the education committee of the London County Council.

Lawrence was originally a supporter of the Conservative Party. According to her biographer, David W. Howell: "As an undergraduate Lawrence was a committed Conservative, a supporter of empire and the Church of England. Her concern with education incorporated a strong emphasis on provision for church schools, which was evident in her subsequent activities as a school manager and a member of the London school board. She had a deep commitment to philanthropy and a thorough appreciation of the principles underlying the work of the Charity Organization Society. In March 1910 she was elected to the London county council (LCC) as a Municipal Reform (Conservative) councillor for affluent West Marylebone." However, under the influence of Beatrice Webb and Sidney Webb, she joined the Fabian Society (1911) and the Labour Party (1912).

After meeting Mary Macarthur, Lawrence joined the Women's Trade Union League and spent the next ten years working for the cause. Despite her monocle and aristocratic manner, Lawrence gradually won over working women in London. As well as helping to organize women workers, Lawrence co-wrote two books on the subject, Women in the Engineering Trades (1917) and Labour Women and International Legislation (1919). During the First World War, Lawrence was a Fabian representative on the War Emergency Workers' National Committee, "a grand coalition of Labour and socialists that avoided divisive debate over the legitimacy of the war and concentrated on practical proposals for working-class amelioration."

In November 1919 Susan Lawrence was elected to Poplar Council. The Labour Party had won 39 of the 42 council seats. In 1921 Poplar had a rateable value of £4m and 86,500 unemployed to support. Whereas other more prosperous councils could call on a rateable value of £15 to support only 4,800 jobless. George Lansbury proposed that the Council stop collecting the rates for outside, cross-London bodies. This was agreed and on 31st March 1921, Poplar Council set a rate of 4s 4d instead of 6s 10d. On 29th the Councillors were summoned to Court. They were told that they had to pay the rates or go to prison. At one meeting Millie Lansbury said: "I wish the Government joy in its efforts to get this money from the people of Poplar. Poplar will pay its share of London's rates when Westminster, Kensington, and the City do the same."

On 28th August over 4,000 people held a demonstration at Tower Hill. The banner at the front of the march declared that "Popular Borough Councillors are still determined to go to prison to secure equalisation of rates for the poor Boroughs." The Councillors were arrested on 1st September. Five women Councillors, including Susan Lawrence, Millie Lansbury and Julia Scurr, were sent to Holloway Prison. Twenty-five men, including George Lansbury and John Scurr, went to Brixton Prison. On 21st September, public pressure led the government to release Nellie Cressall, who was six months pregnant. Julia Scurr reported that the "food was unfit for any human being... fish was given on Friday, they told us, that it was uneatable, in fact, it was in an advanced state of decomposition".

Instead of acting as a deterrent to other minded councils, several Metropolitan Borough Councils announced their attention to follow Poplar's example. The government led by Stanley Baldwin and the London County Council was forced to back down and on 12th October, the Councillors were set free. The Councillors issued a statement that said: "We leave prison as free men and women, pledged only to attend a conference with all parties concerned in the dispute with us about rates... We feel our imprisonment has been well worth while, and none of us would have done otherwise than we did. We have forced public attention on the question of London rates, and have materially assisted in forcing the Government to call Parliament to deal with unemployment."

In the 1923 General Election, Lawrence became Labour MP for East Ham North. Two other rate rebels, John Scurr, and George Lansbury were all elected to the House of Commons. The Labour Party won 191 seats. Although the Conservative Party had 258 seats, Herbert Asquith announced that the Liberal Party would not keep the Tories in office. If a Labour Government were ever to be tried in Britain, he declared, "it could hardly be tried under safer conditions".

On 22nd January, 1924 Stanley Baldwin resigned. At midday, Ramsay MacDonald went to Buckingham Palace to be appointed prime minister. MacDonald had not been fully supportive of the Poplar Councillors since he thought that "public doles, Popularism, strikes for increased wages, limitation of output, not only are not Socialism but may mislead the spirit and policy of the Socialist movement." George Lansbury was therefore not offered a post in his Cabinet.

John Wheatley, the new Minister of Health, had been a supporter of the Poplar Councillors. Edgar Lansbury wrote in The New Leader that he was sure that Wheatley would "understand and sympathise with them in this horrible problem of poverty, misery and distress which faces them." Lansbury's assessment was correct and as Janine Booth, the author of Guilty and Proud of It! Poplar's Rebel Councillors and Guardians 1919-25 (2009), has pointed out: "Wheatley agreed to rescind the Poplar order. It was a massive victory for Poplar, whose guardians had lived with the threat of legal action for two years and were finally vindicated."

During the Labour government of 1924 she was parliamentary private secretary to Charles Trevelyan at the Board of Education. Defeated the the 1924 General Election, Lawrence returned to the House of Commons at a by-election in April 1926.

When Ramsay MacDonald formed a Labour Government after the 1929 General Election, Lawrence became Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of Health. In this post she helped guide the Widows, Orphans and Old Age Pensions Bill through Parliament. David W. Howell, her biographer, has pointed out: " Like others among her generation of Labour women, such as Ethel Bentham and Margaret Bondfield, and in contrast to Lady Astor and some of the younger Labour women like Jennie Lee and Ellen Wilkinson, Lawrence was completely indifferent to pressure to present a feminine image. It was noted how, as a minister, she took no interest in her choice of clothes, sending round to a department store for half a dozen inexpensive dresses to be sent to her office, and briefly raising her head from her papers to select one by pointing with a pencil."

The election of the Labour Government coincided with an economic depression and Ramsay MacDonald was faced with the problem of growing unemployment. In January 1929, 1,433,000 people were out of work, a year later it reached 1,533,000. By March 1930, the figure was 1,731,000. In June it reached 1,946,000 and by the end of the year it reached a staggering 2,725,000. That month MacDonald invited a group of economists, including John Maynard Keynes, J. A. Hobson, George Douglas Cole and Walter Layton, to discuss this problem. However, he rejected all those ideas that involved an increase in public spending.

In March 1931 Ramsay MacDonald asked Sir George May, to form a committee to look into Britain's economic problems. The committee included two members that had been nominated from the three main political parties. At the same time, John Maynard Keynes, the chairman of the Economic Advisory Council, published his report on the causes and remedies for the depression. This included an increase in public spending and by curtailing British investment overseas.

Philip Snowden rejected these ideas and this was followed by the resignation of Charles Trevelyan, the Minister of Education. "For some time I have realised that I am very much out of sympathy with the general method of Government policy. In the present disastrous condition of trade it seems to me that the crisis requires big Socialist measures. We ought to be demonstrating to the country the alternatives to economy and protection. Our value as a Government today should be to make people realise that Socialism is that alternative."

When the May Committee produced its report in July, 1931, it forecast a huge budget deficit of £120 million and recommended that the government should reduce its expenditure by £97,000,000, including a £67,000,000 cut in unemployment benefits. The two Labour Party nominees on the committee, Arthur Pugh and Charles Latham, refused to endorse the report.

The cabinet decided to form a committee consisting of Ramsay MacDonald, Philip Snowden, Arthur Henderson, Jimmy Thomas and William Graham to consider the report. On 5th August, John Maynard Keynes wrote to MacDonald, describing the May Report as "the most foolish document I ever had the misfortune to read." He argued that the committee's recommendations clearly represented "an effort to make the existing deflation effective by bringing incomes down to the level of prices" and if adopted in isolation, they would result in "a most gross perversion of social justice". Keynes suggested that the best way to deal with the crisis was to leave the Gold Standard and devalue sterling. Two days later, Sir Ernest Harvey, the deputy governor of the Bank of England, wrote to Snowden to say that in the last four weeks the Bank had lost more than £60 million in gold and foreign exchange, in defending sterling. He added that there was almost no foreign exchange left.

Philip Snowden presented his recommendations to the MacDonald Committee that included the plan to raise approximately £90 million from increased taxation and to cut expenditure by £99 million. £67 million was to come from unemployment insurance, £12 million from education and the rest from the armed services, roads and a variety of smaller programmes. Arthur Henderson and William Graham rejected the idea of the proposed cut in unemployment benefit and the meeting ended without any decisions being made.

Susan Lawrence and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence both decided to resign from the government if the cuts to the unemployment benefit went ahead: Pethick-Lawrence wrote: "Susan Lawrence came to see me. As Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Health, she was concerned with the proposed cuts in unemployment relief, which she regarded as dreadful. We discussed the whole situation and agreed that, if the Cabinet decided to accept the cuts in their entirety, we would both resign from the Government."

Ramsay MacDonald went to see George V about the economic crisis on 23rd August. He warned the King that several Cabinet ministers were likely to resign if he tried to cut unemployment benefit. MacDonald wrote in his diary: "King most friendly and expressed thanks and confidence. I then reported situation and at end I told him that after tonight I might be of no further use, and should resign with the whole Cabinet.... He said that he believed I was the only person who could carry the country through."

According to Harold Nicolson, the King decided to consult the leaders of the Conservative and Liberal Parties. Herbert Samuel told the King that he should try and persuade MacDonald to make the necessary economies. Stanley Baldwin agreed and said he was willing to serve under MacDonald in a National Government.

After another Cabinet meeting where no agreement about how to deal with the economic crisis could be achieved, Ramsay MacDonald went to Buckingham Palace to resign. Sir Clive Wigram, the King's private secretary, later recalled that George V "impressed upon the Prime Minister that he was the only man to lead the country through the crisis and hoped that he would reconsider the situation." At a meeting with Stanley Baldwin, Neville Chamberlain and Herbert Samuel MacDonald told them that if he joined a National Government it "meant his death warrant". According to Chamberlain he said "he would be a ridiculous figure unable to command support and would bring odium on us as well as himself."

On 24th August 1931 Ramsay MacDonald returned to the palace and told the King that he had the Cabinet's resignation in his pocket. The King replied that he hoped that MacDonald "would help in the formation of a National Government." He added that by "remaining at his post, his position and reputation would be much more enhanced than if he surrendered the Government of the country at such a crisis." Eventually, he agreed to form a National Government.

The Labour Party was appalled by what they considered to be MacDonald's act of treachery. Arthur Henderson commented that MacDonald had never looked into the faces of those who had made it possible for him to be Prime Minister.

On 8th September 1931, the National Government's programme of £70 million economy programme was debated in the House of Commons. This included a £13 million cut in unemployment benefit. Tom Johnson, who wound up the debate for the Labour Party, declared that these policies were "not of a National Government but of a Wall Street Government". In the end the Government won by 309 votes to 249, but only 12 Labour M.P.s voted for the measures.

On 26th September, the Labour Party National Executive decided to expel all members of the National Government including Ramsay MacDonald, Philip Snowden, Jimmy Thomas and John Sankey. As David Marquand has pointed out: "In the circumstances, its decision was understandable, perhaps inevitable. The Labour movement had been built on the trade-union ethic of loyalty to majority decisions. MacDonald had defied that ethic; to many Labour activists, he was now a kind of political blackleg, who deserved to be treated accordingly."

The 1931 General Election was held on 27th October, 1931. MacDonald led an anti-Labour alliance made up of Conservatives and National Liberals. It was a disaster for the Labour Party with only 46 members winning their seats. Lawrence lost her seat for East Ham North.

Although she failed to become MP again, she continued to be a member of the national executive for the Labour Party. Lawrence was a strong critic of the Soviet Union, yet her last significant intervention within the party's national executive in March 1940 was to oppose the expulsion from the party of the pro-Soviet lawyer D. N. Pritt for his position on the Russo-Finnish War. Lawrence lost her seat on the executive in 1941, and afterwards concentrated on transcribing books into Braille.

Jeannie MacKay, Susan Lawrence and Nellie Cressall (1921)

On this day in 1947 Walt Disney testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee. After complaining about how his films were not distributed in the Soviet Union he was asked: "Have you had at any time, in your opinion, in the past, have you at any time in the past had any Communists employed at your studio?" Disney replied: "Yes, in the past I had some people that I definitely feel were Communists." According to Disney they were behind a strike that had taken place at his studio: "Well, it proved itself so with time, and I definitely feel it was a Communist group trying to take over my artists and they did take them over.... I wouldn't go along with their way of operating."

Disney was asked if he believed the Communist Party of the United States should be banned: "Well, I don't believe it is a political party. I believe it is an un-American thing. The thing that I resent the most is that they are able to get into these unions, take them over, and represent to the world that a group of people that are in my plant, that I know are good, 100 per cent Americans, are trapped by this group, and they are represented to the world as supporting all of those ideologies, and it is not so, and I feel that they really ought to be smoked out and shown up for what they are, so that all of the good, free causes in this country, all the liberalisms that really are American, can go out without the taint of communism. That is my sincere feeling on it."

On this day in 1954 President Dwight Eisenhower pledged United States support to South Vietnam. Eisenhower's government was severely concerned about the success of communism in South East Asia. Between 1950 and 1953 they had lost 142,000 soldiers in attempting to stop communism entering South Korea. The United States feared that their efforts would have been wasted if communism were to spread to South Vietnam. Eisenhower was aware that he would have difficulty in persuading the American public to support another war so quickly after Korea. He therefore decided to rely on a small group of Military Advisers' to prevent South Vietnam becoming a communist state.

On this day in 2005 Rosa Parks died. In Montgomery, like most towns in the Deep South, buses were segregated. Rosa Parks and other civil rights activists considered using CORE tactics in Montgomery. However, under pressure from the NAACP, this never took place. Thurgood Marshall, head of the NAACP's legal department, was strongly against these tactics and warned that a "disobedience movement on the part of Negroes and their white allies, if employed in the South, would result in wholesale slaughter with no good achieved."

In early 1955, Claudette Colvin, a 15 year old black girl was dragged off a bus in Montgomery and arrested for not giving up her seat to a white person. The NAACP now agreed to take up the Colvin incident as a test case. It believed that this would result in a similar outcome to the 1954 Supreme Court decision on segregation in education. However, the NAACP decided to drop the idea when they discovered that Colvin was pregnant. They knew that the authorities in Montgomery would use this against them in the propaganda war that would inevitably take place during this legal battle.

On 1st December, 1955, Rosa Parks, left Montgomery Fair, the department store where she worked, and got on the same bus as she did every night. As always she sat in the "black section" at the back of the bus. However, when the bus became full, the driver instructed Rosa to give up her seat to a white person. This had happened to Rosa several times before. In fact, the same bus driver had forced her off the bus in 1943 for committing the same offence. Once again she refused and was arrested by the police. She was found guilty of violating the segregation law and fined.

It was only at this stage, after consulting friends and family, that she decided to approach the NAACP and volunteer to become a test case. This was a brave decision as she knew it would result in persecution by the white authorities. For example, Parks was immediately sacked from her tailoring job with Montgomery Fair.

Martin Luther King, a pastor at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, agreed to help organize protests against bus segregation. It was decided that from 5th December, black people in Montgomery would refuse to use the buses until passengers were completely integrated. King was arrested and his house was fire-bombed. Edgar Nixon suffered the same fate. Others involved in the Montgomery Bus Boycott also had to endure harassment and intimidation, but the protest continued.

For thirteen months the 17,000 black people in Montgomery walked to work or obtained lifts from the small car-owning black population of the city. Eventually, the loss of revenue and a decision by the Supreme Court forced the Montgomery Bus Company to accept integration, and the boycott came to an end on 20th December, 1956. After the success of this campaign, Parks became known as the "mother of the Civil Rights Movement".