Lewis Casson

Lewis Casson, the son of Thomas Casson, a bank-manager, was born in Birkenhead, Cheshire, on 26th October 1875. Soon after he was born the family, that included at this time seven children, moved to Denbigh in Wales and he was educated at Ruthin School.

Thomas Casson was involved in amateur dramatics and used to read the plays of William Shakespeare to the children when they were small. While still at school Lewis played the role of Orlando in As You Like It.

In 1891 the family moved to London where Thomas Casson established a company building theatre organs. After leaving school Casson began working in his father's business. Later he went to college to study chemistry, but then trained as a teacher at St Mark's College, Chelsea, where he gained a teaching certificate.

Casson became a socialist after reading the work of Robert Blatchford. He became a regular reader of The Clarion, a newspaper reflecting the socialist ideas of William Morris, Robert Owen and H. G. Wells. He also attended meetings of the Social Democratic Federation and several times heard its leader, H. M. Hyndman , speak in public. He eventually became a strong supporter of Keir Hardie, the leader of the recently established Labour Party.

Casson eventually became a tutor at St Mark's College. He also acted in plays produced by Charles Fry. These semi-professional productions were staged in halls, swimming-baths and other venues in the East End of London. Fry introduced him to William Poel, who cast him as Don Pedro in Much Ado About Nothing.

In 1903 Harley Granville Barker and John Eugene Verdenne, the co-managers of the Royal Court Theatre, recruited him to appear in The Two Gentlemen of Verona. He stayed with Barker for three repertory seasons and according to one critic, the company "set new standards of acting and production, and were later recognised as the beginning of the modern British theatre". This included eleven works by George Bernard Shaw. Casson appeared as Octavius Robinson in Man and Superman and Adolphus Cusins in Major Barbara. He became friends with Shaw who was one of the founders of the Fabian Society.

In 1908 Casson played Harry Trench in Shaw's Widowers' Houses. The play was a passionate attack on slum landlords. This is one of three plays Shaw published that were termed "unpleasant" because they were intended, not to entertain their audiences but to raise awareness of social problems. The other plays in the group are The Philanderer and Mrs Warren's Profession.

Sybil Thorndike saw Casson in Widowers' Houses and that night she wrote to her brother Russell Thorndike: "Darling Russ, I've seen a man I could marry - it's most absurd. His name is Casson, Lewis Casson... I liked him better than any young man I've ever seen on the stage because he spoke so fast that it woke you up and made you puzzle a bit, instead of going to sleep as a lot of actors who are highbrow make you." Her biographer, Jonathan Croall, wrote: "She had seen his picture outside the theatre that morning, and been attracted by his strong features and nice face... Lewis was good-looking in a stern way, with a strong chin, a determined mouth and an intent and penetrating gaze. While his manner was often reserved or gruff, his intimidating exterior concealed a man of passion, kindness and humour."

May Playfair, the wife of Nigel Playfair, told Sybil Thorndike that he was a good actor, but "rather difficult to get on with". She also told her that he was a socialist. All the actors were interested in politics "but the prince of the lot is this man Casson". Playfair eventually introduced Sybil to Lewis. She later recalled that "when he laughed his face looked quite different, and he's got a really lovely voice... he looked as if he ought to be an engineer or a sailor or something to do with real life - not a bit like an actor, but fearfully highbrow." She wrote to her brother that "he's the sort of man I like, but you needn't worry, he'll never be interested even - he hasn't even looked at me." Thorndike was wrong about this and they were soon spending a lot of time together.

Thorndike wrote to Russell Thorndike about her new boyfriend: "I should imagine he'd never tell a lie - not for any moral reason but simply because he doesn't care what anyone thinks about him... He never talks about himself at all, which is very attractive."

At first Sybil Thorndike disapproved of Casson's socialism. She wrote to her brother: "Do you know anything about politics? I don't, except that you're supposed to vote Conservative if you are respectable, and be anything but a socialist. Well, most of these highbrows are socialist." Thorndike said to Casson: "Whatever do you want to go fussing like this - there's only just time enough to learn about acting without wanting votes and such-like." Casson replied: "Your acting won't be much good if you don't think about the world in which you live and the conditions of the people."

Casson was a strong advocate of women's rights and in Manchester he introduced Thorndike to Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst and Sylvia Pankhurst. Thorndike joined the Women Social & Political Union (WSPU). She considered herself a pacifist and made it clear she was unwilling to take part in violent demonstrations.

Thorndike also joined the Actresses' Franchise League, a group that included Cicely Hamilton, Elizabeth Robins, Kitty Marion, Ellen Terry, Lillah McCarthy, Lena Ashwell, Lily Langtry and Nina Boucicault. The aim of the organisation was "to convince members of the theatrical profession of the necessity of extending the franchise to women" and to produce propaganda shows for suffrage societies.

Later that year Sybil Thorndike wrote to Russell Thorndike: "Lewis Casson has asked me to marry him. I'm so taken aback. He's never even called me by my Christian name. I didn't fall flat on my face when he proposed in the Kardomah restaurant over coffee and toast, but the whole room spun round and so did the houses outside." At the time they were living in Manchester as they were part of a company based at the Gaiety Theatre, established by Annie Horniman.

The couple married in Aylesford on 22nd December, 1908. Elsie Fogerty, the founder of the Central School of Speech and Drama, told Sybil: "You're a lucky girl to have married Lewis Casson. It's the best voice on the stage, the purest production - and I hope you are worthy of it." For their honeymoon they spent two weeks in Buxton and two weeks at Port Madoc. On their return to Manchester, they both appeared in The Silver Box, a play written by John Galsworthy.

In June 1909 Casson and Thorndike and the company staged a three-week season in London at the Coronet in Notting Hill, featuring seven of their best productions. As Jonathan Croall pointed out in his book, Sybil Thorndike: A Star of Life (2008). "They attracted widespread praise from both critics and audiences, especially for their fine ensemble playing."

John Casson was born at Aylesford on 28th October 1909. Soon afterwards, Reverend Arthur Thorndike accepted the living of St. James-the-Less, Westminster. Sybil, Lewis and John went to live in the vicarage in nearby St George's Square. The baby was looked after by Alice Pearce.

In June 1910, Charles Frohman offered Lewis and Sybil Thorndike a season in the United States. This included acting on broadway with leading American actor, John Drew. The following month they began their journey to New York City. They toured the country for a year and only returned to England in July 1911, when Lewis Casson took up the post of director at the Gaiety Theatre.

Lewis and Sybil rented a small semi-detached house at 106 King's Road, Sedgley Park. John and his nurse, Alice Pearce joined them. A second son, Christopher Casson was born on 20th January 1912. Soon afterwards Nelly Kershaw joined the staff. The following month Lewis took a Gaiety company for a six-week season in Canada. During the tour he began an affair with Edyth Goodall, the founder of the Romney Street Group, a forum for non-Christian socialists.

In June 1912 Sybil appeared in Hindle Wakes by Stanley Houghton. The play was directed by Lewis Casson. The plot centred on Fanny (Edyth Goodall), a mill girl, who goes off for a weekend with Alan (J. V. Bryant), her employer's son, and then refuses to marry him, as she wants to retain her economic and social independence. Sybil Thorndike played Beatrice, Alan's fiancée. The play caused a sensation with one leading critic claiming: "To talk of such things familiarly and without restraint, if persisted in on the stage, must inevitably tend to the degradation of public manners."

Lewis Casson continued to put on experimental productions such as a modern interpretation of Julius Caesar with Sybil playing Portia. Charles E. Montague of the Manchester Guardian described it as "a whoop of joy" whereas the Manchester Courier thought it "one of the greatest things the Gaiety has done". However, Annie Horniman disliked it, believing it to be "self-indulgent" and "an example of experiment for experiment's sake". Casson was so upset by these comments he resigned as director of the company.

Diana Devlin, the author of A Speaking Part: Lewis Casson and the Theatre of his Time (1982) wrote about him as he was at this time: "Thirty-eight years old and in the prime of life. Slim and vigorous, with a very upright posture. Those clear blue eyes, which looked so hard at the immediate view that they seemed to see right past it toward some distant horizon. A serious brow, and firmly pressed lips, expressive of his steadfastness. You might not pick him out of a crowd unless you heard his voice - vibrant, with rich harmonics, making everything he said almost more impressive that it was, you might think, with its resonance, its rhythmic sense and its clear intonations, except that through it came the deep conviction behind his words."

The couple returned to London and lived at a house owned by her mother at 40 Bessborough Street in Pimlico. Lewis was offered a temporary job as artistic director of the Scottish Repertory Theatre in Glasgow. Sybil, who was pregnant, stayed in London and gave birth to Mary Casson on 22nd May, 1914.

War was declared on 4th August 1914. As a socialist, Lewis Casson opposed the idea of what he considered to be an imperialist war and sympathised with the stance taken by the leaders of the Labour Party such as Keir Hardie and Ramsay MacDonald. However, most of his friends and relatives did respond to the call made by Lord Kitchener on 6th August to join the armed forces. This included his brother William Casson (London Regiment) and Sybil's two brothers, Russell Thorndike and Frank Thorndike (Westminster Dragoons).

As his biographer, Diana Devlin, pointed out: "Like so many Socialists, he had strongly resisted the idea of war. In a world where there was so much work to be done, so many human needs to attend to, what place was there for military expense and national aggression? He sympathised with the Labour demonstration of August 2nd, which Keir Hardie had addressed... He felt torn between the straightforward and courageous patriotism of his brother and the pacific idealism of the neutralists."

Lewis Casson eventually decided that decided that he would also join up. Like most of the Labour Party, the Women Social & Political Union, he trade union movement and other left-wing organisations, he eventually decided to support the war in the hope that at the end of the conflict the people would be rewarded by the government introducing large-scale political and social reforms.

To do so he had to lie about his age as at 39 he was four years over the age limit. He went to the Duke of York's Barracks in Chelsea and joined the Army Service Corps. His wife, Sybil Thorndike, later recalled: "I hated, hated the thought of his fighting Germans, because I'd worked with German musicians, and had such lovely friendships with people of that country. It seemed a most hideous and wretched betrayal of that friendship."

Casson was sent to St. Albans where he met up with his actor and playwright friend Harold Chapin, who he had worked with at the Gaiety Theatre. He was initially put in charge of the cook-house. Later he was transferred to Mechanical Transport to drive lorries.

In January 1915 he was sent to the Western Front. He took part in the offensive at Loos where his brother, William Casson and his friend, Harold Chapin, were both killed. Despite suffering over 50,000 casualties, the British Army failed to break up the German front-line.

Sybil Thorndike continued to work at the Old Vic but after a Zeppelin raid on London killed 28 people on 31st May 1915, her children were sent to live in Dymchurch with her mother, Alice Pearce and Nelly Kershaw. Sybil was pregnant again and she gave birth to Anne Casson in November 1915. Later the family moved to Kingsdown in Kent. As John Casson pointed out in his book, Lewis and Sybil (1972): "Granny swept Alice and Nelly, Christopher and Mary off to the vicarage to keep them out of harm's way... It was the beginning of a long period when Alice and Nelly ruled our lives."

In 1916 Casson was given a commission in the Royal Engineers (Special Brigade) to work on poison gas. John Casson later explained: "It was found that he had a half-completed chemistry degree and so he was thought to be just the fellow who would know about gas." Within a few months he was promoted to captain with his own company, carrying out the deadly work of preparing and placing cylinders and projectors of poison gas along the frontline. Casson was very active in this work during the Battle of the Somme.

Frank Thorndike died of his wounds on 17th August 1917. John Casson later recalled: "Nelly gently told us the news of Frank's death in France. It didn't seem to us the news of Frank's death in France. It didn't seem to us to be a very terrible thing because Sybil had always said that when people died they went off to a place where everybody was happy."

The following year Casson was sent on a mission to lay phosgene cylinders in Arras. During the operation he received a shrapnel wound in his shoulder. He was taken to hospital in France and was later sent back to England. In August 1917 he discovered he had been awarded the Military Cross for this mission.

In January 1918 Major Casson was sent back to the Western Front in order to continue with his work on poison gas. A few months later Casson invented a more efficient mechanism for gas missiles. In the autumn of 1918 he was sent to Washington to discuss gas warfare.

On his return to civilian life Casson suffered from bouts of depression. Some of his friends believed that this was caused by his wartime experiences. However, some family members believed he was suffering the first serious attack of a hereditary depressive illness.

Casson was also upset by the decision of Harley Granville Barkerto abandon his interest in the theatre. In July 1918 he had married Helen Huntington, a wealthy widow. According to his biographer, Diana Devlin, Casson believed there were other reasons for this decision: "Was there, as Lewis later came to think, some mystery about Barker's post-war career, and his involvement with the Secret Service, which, if uncovered, might explain his change of direction and his almost complete severance from the theatre."

After the war Casson resumed his career in the theatre. He joined forces with Bruce Winston and with the help of Lord Howard de Walden, rented the Holborn Empire from Charles Gulliver. The partnership was launched in February 1920. They began with The Trojan Women, Candida and Medea.

Casson's next venture was Grand Guignol, an idea that had come from Paris. The plays were in a variety of styles, but the most popular and best-known were the horror plays. In September 1920 Casson directed The Hand of Death by Andre de Lorde, a play in which a doctor used his own daughter for an experiment in resuscitation and she regained life just sufficiently to strangle him. The play caused a sensation and one critic, St. John Greer Ervine, wrote: "This sort of thing may interest overfed voluptuaries and creepy-crawly people with flabby insides, but I cannot imagine that this fashion will continue to be popular."

Casson's horror plays caused problems with the Lord Chamberlain, who was in charge of censoring plays. Diana Devlin argues that Casson anticipated Alfred Hitchcock by producing plays that relied on the audience's imagination. Russell Thorndike appeared in several of these horror plays. He later claimed that: "He (Casson) used suggestion rather than blood-dripping props. We frightened our audiences rather than disgusted them."

In July 1922 Casson directed Sybil Thorndike in Jane Clegg a play by St. John Greer Ervine and Scandal, a social melodrama by Henri Bataille. This was followed by The Cenci by Percy Bysshe Shelley. The play had been banned ever since it was written in 1819 because of a story that involves a girl (Beatrice) being raped by her father (Count Cenci). Beatrice then arranges the murder of Cenci and this results in her being tortured.

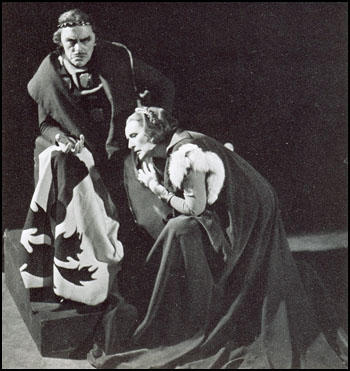

In 1923 George Bernard Shaw wrote the play Saint Joan. The London premiere, which opened on 26th March 1924 at the New Theatre, was produced and directed by Lewis Casson and starred Sybil Thorndike, the actress for whom he had written the part. Shaw helped to rehearse the cast. As Casson later pointed out: "He was always patient, but quite persistent in getting eventually exactly what he wanted, as far as the actor was capable of it. I never remember his teaching any actor an intonation parrot-like, but he had the power, the skill and the vitality to make his version seem the obvious and only one."

The play was a great success and the weekly takings broke the New Theatre record. Elsie Fogerty later wrote: "It achieved at the New Theatre in 1924, that rare triumph of a perfect cast, a perfect production and that curious fitness to the public mood of the day which together showed it to stand apart from all other plays of Shaw." Sybil Thorndike also received considerable praise for her performance as Joan of Arc.

Casson also directed the controversial play, Man and the Masses, written by the Marxist playwright, Ernst Toller. It was the first time that the play had been performed outside Berlin, Moscow and New York. Casson also did seven plays for the recently established British Broadcasting Company. The following year he provided an acclaimed version of Henry VIII, that ran for over three months.

Lewis Casson remained active in politics and as a socialist he fully supported the General Strike. The Trade Union Congress called the strike on the understanding that they would then take over the negotiations from the Miners' Federation. The main figure involved in these negotiations was Jimmy Thomas. Casson lent his car to the leaders during the dispute and told his wife: "this strike will go on and on until the government comes to its senses. The spirit of the people is marvellous."

On the 7th May, Sir Herbert Samuel, Chairman of the Royal Commission on the Coal Industry, approached the Trade Union Congress and offered to help bring the strike to an end. Without telling the miners, the TUC negotiating committee met Samuel and worked out a set of proposals to end the General Strike. These included: (1) a National Wages Board with an independent chairman; (2) a minimum wage for all colliery workers; (3) workers displaced by pit closures to be given alternative employment; (4) the wages subsidy to be renewed while negotiations continued. However, Samuel warned that subsequent negotiations would probably mean a reduction in wages. These terms were accepted by the TUC negotiating committee, but were rejected by the executive of the Miners' Federation.

Casson was appalled by what he considered was a betrayal of the miners. For several months the miners held out, but by October 1926 hardship forced men to begin to drift back to the mines. By the end of November most miners had reported back to work. However, many were victimized and remained unemployed for many years. Those that were employed were forced to accept longer hours, lower wages and district agreement.

Casson's main success in 1926 was Granite by Clemence Dane. He played the role of the "Nameless Man" and Sybil Thorndike gave another impressive performance as Judith. The critic St. John Greer Ervine argued that "Lewis Casson's acting as the Nameless Man was powerful in its sinister quiet. There was something unearthly and inhuman about this figure."

Lewis Casson became known as a demanding director. On one occasion he told a young actor he was pleased with his performance. "I'm glad your're satisfied, sir." the man replied. "I said I was pleased," Casson barked, "I am never satisfied."

Macbeth (1926) was followed by The Greater Love (1927), a romantic Russian melodrama by J. B. Fagan. The cast of the play included Sybil Thorndike and Charles Laughton. Casson returned to acting and was Shylock in the Merchant of Venice. Lewis and Sybil toured South Africa in 1928.

Lewis Casson remained active in politics and as a socialist he was delighted when in the 1929 General Election the Labour Party won 288 seats, making it the largest party in the House of Commons. Ramsay MacDonald became Prime Minister, but had to rely on the support of the Liberals to hold onto power.

The election of the Labour Government coincided with an economic depression and Ramsay MacDonald was faced with the problem of growing unemployment. MacDonald asked George May, to form a committee to look into Britain's economic problem. When the May Committee produced its report in July, 1931, it suggested that the government should reduce its expenditure by £97,000,000, including a £67,000,000 cut in unemployment benefits. MacDonald, and his Chancellor of the Exchequer, Philip Snowden, accepted the report but when the matter was discussed by the Cabinet, the majority voted against the measures suggested by May.

Ramsay MacDonald was angry that his Cabinet had voted against him and decided to resign. When he saw George V that night, he was persuaded to head a new coalition government that would include Conservative and Liberal leaders as well as Labour ministers. Most of the Labour Cabinet totally rejected the idea and only three, Philip Snowden, Jimmy Thomas and John Sankey agreed to join the new government. MacDonald was determined to continue and his National Government introduced the measures that had been rejected by the previous Labour Cabinet. Labour MPs were furious with what had happened and MacDonald was expelled from the Labour Party.

Miles Malleson, was a socialist writer who was appalled by the cut in unemployment benefits and approached Lewis Casson about producing a play about the plight of the working-class. It was eventually decided to collaborate on a play about the Tolpuddle Martyrs. Casson agreed to play the role of George Loveless, the leader of the group transported for attempting to establish a trade union. Casson toured Six Men of Dorset all over England, visiting mainly the industrial towns and those places suffering from high unemployment.

In September 1937 Casson worked with J. P. Priestley for the first time when he directed I Have Been Here Before. The play dealt with the theory of "time-warps" that had been developed by Peter Ouspensky. The cast included Casson and Wilfred Lawson. The following year he directed Lawrence Olivier in Coriolanus. The critic, James Agate noted: "Vocally Mr. Olivier's performance is magnificent: his voice is gaining depth and resonance and his range of tone is now extraordinary." This was followed by Henry V and Man and Superman. Casson also played the part of Sir Anthony Absolute in The Rivals, a play written by Richard Brinsley Sheridan.

Casson was asked to head a Old Vic tour around the Mediterranean. The British Council sponsored the tour to improve various cultural relations. The trip that lasted between January and April, 1939, included visits to Portugal, Italy, Egypt and Greece. The company included Alec Guinness, Anthony Quayle, Cathleen Nesbitt, Andrew Cruikshank, Curigwen Lewis and Cecil Ramage. Some newspapers complained about the trip to a country ruled by a fascist dictator, Benito Mussolini. Casson defended the decision: "I feel that at a time like this, when the world is in a state of strain and tension, it's particularly important not to let what, after all, are political differences interfere with the ordinary human relations between nations."

On his return to London Casson played Colonel Pickering in a revival of Pygmalion. On the outbreak of the Second World War Casson joined the Air Raids Precaution Service in Chelsea. His son John Casson joined the Royal Navy but Sybil Thorndike and their son and daughter, Christopher Casson and Anne Casson were pacifists and refused to take part in the war effort.

In 1939 Herbrand Sackville, 9th Lord de la Warr, the President of the Board of Education, established the Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts (CEMA) was formed to promote amateur and professional arts through the country. Casson was appointed as Advisor on Professional Theatre for CEMA. Soon afterwards Casson talked to the CEMA about the possibility of turning the Old Vic into a state-subsidised National Theatre.

The following year Casson was approached by John Gielgud about joining forces with Harley Granville Barker to direct him in King Lear. Barker, who had been living in retirement in France, agreed to become involved in the project as long as he was allowed to do it anonymously. The play opened in April 1940 with a cast that included Nicholas Hannen, Jack Hawkins, Cathleen Nesbitt, Fay Compton, Jessica Tandy, Stephen Haggard and Harcourt Williams.

During this production news reached Lewis Casson that his son, John Casson, who was in charge of a bomber squadron on the Arc Royal, was shot down over Norway. He was told he was "missing, believed killed". It was some time before they heard that he survived and was a prisoner-of-war in Germany.

In April 1940 Casson took the lead role in an Old Vic production of Macbeth. The company then went on a CEMA sponsored tour of South Wales. The first performance was in Newport. That night, the manager of the theatre's house, where Casson and his wife Sybil Thorndike were to have stayed, was completely destroyed in a Luftwaffe air raid. His two children were also killed.

The company also performed in the Rhondda Valley. Sybil later told of how she spoke at a large gathering of educationalists, and the local dignitary introduced her as "a famous member of the oldest profession in the world. The ten week tour was a great success and box-office takings were so good that the Old Vic did not have to call upon the guarantee against loss which the CEMA had provided.

In 1941 Casson took Macbeth to Northern England (January) and North Wales (March). He also directed Medea and Candida at the Old Vic and in September took the productions to South Wales. The following year he toured North Wales as well as directing Jacob's Ladder, a play by Laurence Housman.

During this period Casson began working with Tyrone Guthrie. He introduced him to Douglas Campbell, a former lorry driver who wanted to become an actor. Campbell was an ardent pacifist and during their first meeting they had a heated argument over the war. After that first meeting, Casson said: "that's an opinionated young man. But I like him." He later married Casson's daughter, Anne Casson.

In June 1943 Casson appeared in The Moon is Down, a novel about Nazi-occupied Europe that had been written by John Steinbeck had been turned into a play. Also in the cast was Paul Schofield who played the part of a young miner sentenced to death. The following year he directed Sheppy by Somerset Maugham.

Casson also played an important role in the establishment of the Actors' Association. This organization was merged with the Stage Guild to form the British Actors' Equity Association. Casson served as president of Equity between 1941 to 1945.

In June 1945 Casson was knighted. Later that year he visited occupied Germany. Casson was appalled at the amount of war damage he saw. When he was in Hamburg he wrote to Sybil Thorndike: "We are supposed to pride ourselves on the accuracy of our bombing, so we can only conclude that the smashing up of miles and miles of fine workmen's flats and small houses was deliberate, for whole districts of wealthy homes are almost untouched."

Casson became a controversial figure when he questioned the idea that the German people should be held responsible for the concentration camps. He stated that if that was the case, the British people should be held responsible for the blanket-bombing of German cities. He also condemned what he called "Daily Express propaganda" about atrocities committed by the Red Army.

Casson campaigned for the Labour Party during the 1945 General Election. He was delighted at the party's landslide victory. "Well, Labour will have to get to work this time. There can be no shirking on the ground that they had insufficient parliamentary majority."

In August 1945 Casson spoke out in protest against using the atom bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He argued: "How far we have travelled down the Nazi road." He rejected the idea that nuclear weapons would lead to a peaceful world. Casson remarked that this had been said "at every stage since the invention of gunpowder."

In April 1946 Casson directed and acted in Man and Superman. Two months later he played Woodrow Wilson in the play In Time to Come. In 1947 he was the Duke of York in Richard II, a play directed by Ralph Richardson at the New Theatre. He also took the leading role of the idealistic history professor in The Linden Tree, a play by J. B. Priestley. His grand-daughter, Diana Devlin, commented: "A man of integrity and dedication, fierceness and kindness, a lover of family, work and beauty... having to play nearer to his real self than ever before, was able to express some of his own ideals through it."

Casson went into semi-retirement at the age of 75. The couple purchased Cedar Cottage at Wrotham. He still played the occasional role. This included The Winter's Tale (1951), Much Ado About Nothing (1952) and Oedipus Rex (1953).

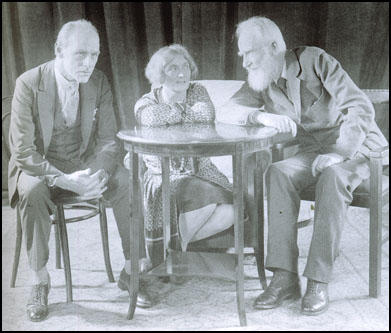

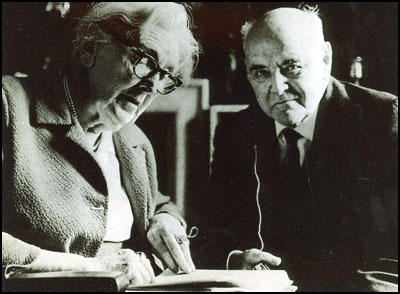

The following year Casson and Sybil Thorndike devised a programme of literary readings. They took this on a tour of Australia and New Zealand (1954), India, Hong Kong and Malaya (1955) and South Africa, Rhodesia, Kenya, Israel and Turkey (1956). Diana Devlin argued: "I doubt if another actor could speak poetry more beautifully than Lewis. He prepared each piece elaborately, marking the text until it looked like a musical score, to remind himself of the significance and shape of each phrase... Each tiny pause, each subtle inflection, was designed to reveal to the audience the developing pattern of the piece, and to carry them through to the next moment."

In 1959 Lewis and Sybil celebrated their golden wedding by appearing together in Eighty in the Shade, a play specially written for them by Clemence Dane. One critic, Cecil Wilson, pointed out in the Daily Mail: "To make it a worthy Casson occasion it should at least be a pair of parts, but Sir Lewis takes such a modest back seat that the evening rests entirely on his enchanting wife."

In the early 1960s Lewis developed eye-problems that made reading impossible. With the help of Sybil Thorndike he managed to appear in Uncle Vanya (July, 1962), Queen B (September 1963) and Arsenic and Old Lace (February, 1966). His last appearance was as the Lord Chief Justice in Night Must Fall by Emlyn Williams.

Lewis Casson died in the Nuffield Nursing Home on 16th May 1969.

Primary Sources

(1) Sybil Thorndike, letter to Russell Thorndike (January 1908)

When he (Lewis Casson) laughed his face looked quite different, and he's got a really lovely voice... he looked as if he ought to be an engineer or a sailor or something to do with real life - not a bit like an actor, but fearfully highbrow.... I should imagine he'd never tell a lie - not for any moral reason but simply because he doesn't care what anyone thinks about him... He never talks about himself at all, which is very attractive.

(2) Diana Devlin, A Speaking Part: Lewis Casson and the Theatre of his Time (1982)

Thirty-eight years old and in the prime of life. Slim and vigorous, with a very upright posture. Those clear blue eyes, which looked so hard at the immediate view that they seemed to see right past it toward some distant horizon. A serious brow, and firmly pressed lips, expressive of his steadfastness. You might not pick him out of a crowd unless you heard his voice - vibrant, with rich harmonics, making everything he said almost more impressive that it was, you might think, with its resonance, its rhythmic sense and its clear intonations, except that through it came the deep conviction behind his words.

(3) Jonathan Croall, Sybil Thorndike: A Star of Life (2008)

Sybil and Lewis were in Dymchurch on 28 June 1914 when the Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo. A few days later, standing on the beach looking across to France just thirty miles away, Lewis announced: "There's going to be war in Europe." According to Russell, Sybil's instant reply was: "Thank God you're not a soldier then." The war was to bring tragedy and hardship to her and her family, but prove a rich and rewarding period in her development as an actress.

She and her family moved back to Pimlico just as war was declared on 4 August. The days that followed were marked by widespread fervour, with crowds cheering, waving flags, riding on taxi roofs and singing patriotic songs, as thousands of soldiers said goodbye to their families. In the theatre new productions were suspended and old ones closed, leaving Sybil, Lewis and thousands of others unemployed. On 6 August Lord Kitchener issued the call to arms, "Your King and Country Need You". Russell had joined the Westminster Dragoons the previous year, and Frank, now 20, enlisted in the same regiment, but without telling the family.

Within three weeks the brothers had set sail in high spirits for the Middle East. Sybil's father wanted to enlist, but at 60 was barred from doing so, even as a chaplain. Lewis meanwhile was in a dilemma. As a socialist he opposed the idea of war, and sympathised with the anti-war elements in the Labour Party, led by Keir Hardie. He was also attracted to the idealistic pacifism of the Neutrality Committee, which included Gilbert Murray and Ramsay MacDonald. But he also felt it his duty to defend his country. On the day he and Sybil saw Russell and Frank off, he told Sybil that he had to join up, in what he hoped would be "a war to finish war for ever".

Sybil was naturally unhappy: "I hated, hated the thought of his fighting Germans, because I'd worked with German musicians, and had such lovely friendships with people of that country," she later wrote. "It seemed a most hideous and wretched betrayal of that friendship." But having discussed the matter with her parents, who supported Lewis' view and promised to look after Sybil and the children, she reluctantly gave way. While she opposed the war, she was not yet a full-blooded pacifist, believing that "this country is going to smash the beastly engine of war and make a new world, something bigger and better than has ever been known before".

Although the age-limit for recruitment had been raised to thirty-five, Lewis still had to slice four years off his age in order to join the Army Service Corps in St Alban's, where he was soon fully occupied. "He is driving a motor lorry and being a cook and doing stews, and washing up, and working from 4.15am all the livelong day," Sybil told a Manchester friend in October. "I believe he is quite enjoying himself - he certainly is developing unsuspected talents!" But the war was now impinging on her life too, as wounded soldiers and Belgian refugees poured into London. "Isn't this war awful? One really cannot believe all the tragedy and frightfulness is true, but when one sees the wounded here in London it does suddenly come home."

(4) John Casson, Lewis & Sybil (19xx)

We stayed at Kingsdown off and on until early in 1918, and in June of 1917 1 saw my first piece of real life serious drama without any acting. We were in the little sitting-room one afternoon and Sybil was kneeling on the floor helping us with some game. Suddenly there was a loud knocking. "Open the front door, John darling," said Sybil and I reached up and undid the latch. A tall fat girl stood outside who thrust into my hand an orange envelope saying as she did so, "Telegram for yer mum." Never as long as I live shall I forget the look of abject terror on Sybil's face as she tore open the telegram. In those days of long casualty lists telegrams were frequent and horrifying, and Sybil fully expected to read that Lewis had been killed in action. But as she read she gave a great sigh of relief and said: "Thank God, he's wounded." At 7 years old I was astonished that she should be so pleased to know that Lewis was wounded until she told me that this would probably mean he would be coming home soon. And some weeks later when she came on her next visit, she brought Lewis with her.

He came wearing the uniform of a captain in the Royal Engineers, for he had been commissioned in 1916. It was found then that he had a half-completed chemistry degree and so he was thought to be just the fellow who would know about gas. One night he had been ordered to lay a large number of cylinders of phosgene out in No Man's Land. There was himself, a sergeant and a dozen privates from the R.E.s and he was to have had a large carrying party of a hundred Australians. The Australians, for some reason, failed to turn up and so Lewis took his baker's dozen engineers and they did the job on their own. Lewis got a Military Cross for the night's work and a wound in his shoulder from a piece of shrapnel. One night, forty years later, he told the story of it at a dinner in Melbourne. He never understood why the Australians were not very enthusiastic when he thanked them for his M.C.!

(5) Diana Devlin, A Speaking Part: Lewis Casson and the Theatre of his Time (1982)

I doubt if another actor could speak poetry more beautifully than Lewis. He prepared each piece elaborately, marking the text until it looked like a musical score, to remind himself of the significance and shape of each phrase... Each tiny pause, each subtle inflection, was designed to reveal to the audience the developing pattern of the piece, and to carry them through to the next moment.