On this day on 22nd November

On this day in 1808 Thomas Cook, the only child of John Cook, a labourer, was born at Melbourne, South Derbyshire. His father died in 1812, and his mother remarried James Smithard. This did not improve the family's financial circumstances and Thomas was forced to leave school at the age of ten and found work as a gardener's boy on Lord Melbourne's estate.

Cook attended the local Methodist Sunday School. However, when he reached the age of 13, his mother persuaded him to become a Baptist. Soon afterwards he started as an apprentice as a wood-turner and cabinet-maker with his uncle, John Pegg, who was also a strong Baptist.

During this period Cook was described as "an earnest, active, devoted, young Christian". He soon became a teacher at the Sunday School and eventually was appointed as its superintendent. At seventeen Thomas joined the local Temperance Society and over the next few years spent his spare-time campaigning against the consumption of alcohol.

In 1827 Cook abandoned his apprenticeship to become an itinerant village missionary, on a salary of £36 a year. His biographer, Piers Brendon, points out: "His job was to spread the Word by preaching, distributing tracts, and setting up Sunday schools throughout the south midland counties. Thus began a career in travel.... Cook, a young man with a commanding presence and black penetrating eyes in which some discerned a gleam of fanaticism... All his life he remained a strict and ardent Baptist, although he was tolerant of other protestant sects. Religion gave him a strong desire to help the downtrodden and his political inclinations were liberal."

Cook married Marianne Mason (1807–1884) on the 2nd March, 1833, and settled in Market Harborough. The Baptist church could no longer afford to pay him as a preacher and so set up in trade as a wood-turner. He also became an active member of the local Temperance Society. Cook made speeches and published pamphlets pointing out the dangers of alcohol consumption. He also arranged large group picnics where participants were, according to the Temperance Messenger, sustained with "biscuits, buns and ginger beer". In 1840 Cook decided to make a career out of his temperance beliefs and founded the Children's Temperance Magazine.

In 1841 Cook had the idea of arranging an eleven-mile rail excursion from Leicester to a Temperance Society meeting in Loughborough on the newly extended Midland Railway. Cook charged his customers one shilling and this included the cost of the rail ticket and the food on the journey. The venture was a great success and Cook decided to start his own business running rail excursions. Cook later recalled that this was "the starting point of a career of labour and pleasure which has expanded into … a mission of goodwill and benevolence on a grand scale".

Thomas Cook set up as a bookseller and printer in Leicester. He specialized in temperance literature but also produced books aimed at a local market such as the Leicester Almanack (1842) and Guide to Leicester (1843). He also opened up temperance hotels in Derby and Leicester and continued to organize excursions. The author of Thomas Cook: 150 Years of Popular Tourism (1991) has pointed out: "In 1845, having won a reputation as an entrepreneur who could obtain cheap rates from the railway companies for large parties, he undertook his first profit-making excursion - to Liverpool, Caernarfon, and Mount Snowdon. Cook wrote a handbook which resembled in essential respects the modern tour operator's brochure."

In 1846 Cook took 500 people from Leicester on a tour of Scotland that involved visits to Glasgow and Edinburgh. One of his greatest achievements was to arrange for over 165,000 people to attend the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park in 1851. With the profits from his travel business Cook was able to "abandon the printing trade, give considerable sums to poor relief, promote the erection of a Temperance Hall in Leicester, and finance the rebuilding of his Commercial and Family Temperance Hotel". These were very popular and with the profits from his travel business Cook was able to "abandon the printing trade, give considerable sums to poor relief, promote the erection of a Temperance Hall in Leicester, and finance the rebuilding of his Commercial and Family Temperance Hotel".

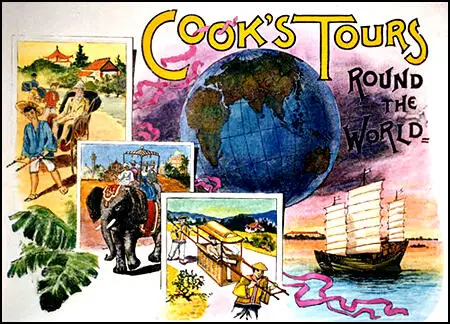

Cook's travel business was badly damaged in 1862 when the Scottish railway companies refused to issue any more group tickets for Cook's popular tours north of the border. Cook now decided to take advantage of new rail links for the conveyance of large numbers of tourists to the continent. In his first year he arranged for 2000 visitors to travel France and 500 to Switzerland. In 1864 Cook began taking tourists to Italy.

Cook's tours of Europe, resulted in him being described as the "Napoleon of Excursions". However, he had his critics. Charles Lever, writing in Blackwood's Magazine, commented that Cook was guilty of swamping Europe with "everything that is low-bred, vulgar and ridiculous". Others complained about the bad taste of taking tourists to the battlefields of the American Civil War.

Cook moved his business to London. His son John managed the London office of the company that was now known as Thomas Cook & Son. John helped to expand the company by opening offices in Manchester, Brussels, and Cologne. In 1869 the company arranged tours of Egypt and the Holy Land, something he described as "the greatest event of my tourist life".

Thomas Cook had a difficult relationship with his son and only made him a partner in 1871. The author of Thomas Cook: 150 Years of Popular Tourism (1991) has suggested: "His reluctance was probably due to disputes between the two men, mainly over financial matters. Unlike Thomas, John believed that business should be kept separate from religion and philanthropy. He also upset his father by being more adventurous in investing money. He opened a hotel at Luxor and refurbished the Nile steamers of the khedive, from whom he obtained the passenger agency, thus helping to make Egypt a safer and more attractive destination."

By 1872 Thomas Cook & Son was able to offer a 212 day Round the World Tour for 200 guineas. The journey included a steamship across the Atlantic, a stage coach from the east to the west coast of America, a paddle steamer to Japan, and an overland journey across China and India.

Thomas Cook continued to disagree with his son about the way the company should be run. After a serious dispute in 1878, Thomas decided to retire to Thorncroft, the large house which he had built on the outskirts of Leicester, and allow John Cook to run the business on his own.

Piers Brendon has argued: "Cook led a lonely life after the deaths of his unmarried daughter Annie (who drowned in her bath, apparently overcome by fumes from a new gas heater) in 1880 and his wife four years later. He continued to travel, however, making his final pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 1888. Much of his time and money were spent, as they had been throughout his career, in work for the Baptist church, the temperance movement, and other charities. He did not attend the firm's silver jubilee celebrations in 1891; whether this was because of blindness and physical incapacity or because John did not want him there is not clear." Thomas Cook died at Knighton, Leicester, on 18th July 1892.

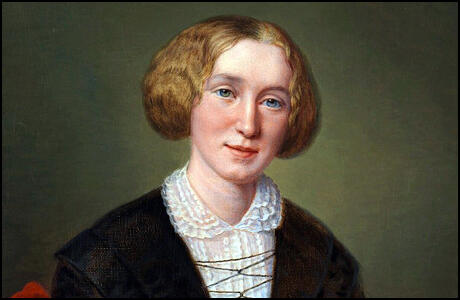

On this day in 1819 Mary Ann Evans (George Eliot) was born. She wrote seven novels: Adam Bede (1859), The Mill on the Floss (1860), Silas Marner (1861), Romola (1862–63), Felix Holt, the Radical (1866), Middlemarch (1871–72) and Daniel Deronda (1876).

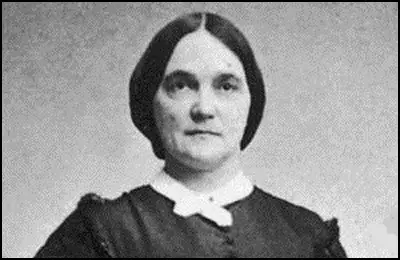

On this day in 1886 Mary Boykin Chesnut died. Mary Miller was born in Pleasant Hill, South Carolina, on 31st March, 1823. The daughter of Stephen Miller, the governor of South Carolina, and Mary Boykin, Mary attended private schools in Camden and Charleston.

On 23rd April, 1840, Mary married James Chesnut, the owner of a large plantation in Mulberry, South Carolina. When Chesnut was elected to the Senate in 1858, Mary accompanied her husband to Washington.

On the outbreak of the American Civil War Chesnut joined the Confederate Army and became a military aide to General P. G. T. Beauregard. Promoted to the rank of general, Chesnut worked as an advisor to President Jefferson Davis. Mary always accompanied her husband during the war and spent time in Charleston, Montgomery, Columbia and Richmond.

Chesnut was opposed to slavery but believed in the right of the Southern states to leave the Union. Between February, 1861 and July, 1865, Chesnut kept a 400,000 word diary of the conflict.

After the war Mary wrote three novels. However, none of these were published during her lifetime. Mary Boykin Chesnut died in Camden, South Carolina, on 22nd November, 1886. Her book, A Diary From Dixie, was not published until 1905.

On this day in 1910 Elsie Bowerman hears about her mother being assaulted by the police on a Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) demonstration. Elsie Bowerman was born in Tunbridge Wells on 18th December 1889. She was educated at Wycombe Abbey School (1901–7) before going to finishing school in Paris.

According to Helena Wojtczak: "Around 1907, the widowed Edith Bowerman, now 43, married 67-year-old Alfred Benjamin Chibnall, a wealthy farmer. This alliance remains mysterious. Hastings Rates books and street directories show no trace that the couple ever lived together."

In 1908 Elsie Bowerman went to Girton College. The following year Bowerman and her mother joined the WSPU. She established a branch in Girton and in October 1910 she invited Margery Corbett-Ashby to speak to the students. Later she arranged for Constance Lytton to speak at the college. She also sold copies of Votes for Women and gave away free copies to those who could not afford the.

On 22nd November, Elsie's mother, Edith Chibnall joined a WSPU deputation to the House of Commons. She was assaulted by a policeman. She explained in a letter to Elsie: "He caught me by the hair and flinging me aside he said, 'Die, then!' I found afterwards that so much force had been used that my hairpins were bent double in my hair and my sealskin coat was torn to ribbons." Elsie replied: "So sorry you have had such a bad time. It is sickening that this endless fighting has to go on. I am frightfully sorry Mrs. Pankhurst & Mrs. Haverfield were arrested... It is a great pity to lose all our best people just before the Election. I hope you won't go on any more raids. I think you have done your share for this week."

In 1911 Bowerman graduated with a second-class degree in medieval and modern languages. She now moved to St Leonards where her mother had established a branch of the WSPU. Bowerman helped her mother run the WSPU shop on the Grand Parade at Hastings. Bowerman was also a paid full-time organizer for the organization.

Elsie Bowerman and her mother decided to take a holiday in the Ohio. On 15th April 1912 they were passengers on the Titanic when it sank. As they were both first-class passengers every effort was made to save them. Elsie later wrote: "The silence when the engines stopped was followed by a steward knocking on our door and telling us to go on deck. This we did and were lowered into life-boats, where we were told to get away from the liner as soon as we could in case of suction. This we did, and to pull an oar in the midst of the Atlantic in April with ice-bergs floating about, is a strange experience."

On the outbreak of the First World War, Bowerman supported the decision by Emmeline Pankhurst, to help Britain's war effort. In 1914 Eveline Haverfield founded the Women's Emergency Corps, an organisation which helped organize women to become doctors, nurses and motorcycle messengers. Christabel Marshall described Haverfield as looking "every inch a soldier in her khaki uniform, in spite of the short skirt which she had to wear over her well-cut riding-breeches in public." Appointed as Commandant in Chief of the Women's Reserve Ambulance Corps, Haverfield was instructed to organize the sending of the Scottish Women's Hospital Units to Serbia.

On 5th July, 1916, Elsie Bowerman wrote to her mother: "Mrs Haverfield has just asked me to go out to Serbia at the beginning of August, to drive a car - May I go? I know Miss Whitelaw would let me off Wycombe to go. It is what I've been dying to do & drive a car ever since the war started. I should have to spend the week after the procession learning to drive - the cars are Fords - if I went I would come home when I come back I would not have to go to W.A. It is really like a chance to go to the front. They want drivers so badly. So do say yes - It is too thrilling for words."

According to Elizabeth Crawford: "In September 1916 Elsie Bowerman sailed to Russia as an orderly with the Scottish women's hospital unit, at the request of the Hon. Evelina Haverfield, a fellow suffragette whom she had known for several years. With this unit she travelled via Archangel, Moscow, and Odessa to serve the Serbian and Russian armies in Romania. The women arrived as the allies were defeated, and were soon forced to join the retreat northwards to the Russian frontier."

While awaiting her passage home, in March 1917, Elsie Bowerman witnessed the overthrow of Tsar Nicholas II in St Petersburg. She wrote to her mother: "Throughout we have met with the utmost politeness & consideration from everyone. Revolutions carried out in such a peaceful manner really deserve to succeed. Today weapons only seem to be in the hands of responsible people - not as yesterday, carried in many cases by excited youths. Heard that the ministers have now surrendered. Some have been shot, or shot themselves."

In 1917 Elsie Bowerman became a member of the The Women's Party, an organisation established by Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst. Its twelve-point programme included: (1) A fight to the finish with Germany. (2) More vigorous war measures to include drastic food rationing, more communal kitchens to reduce waste, and the closing down of nonessential industries to release labour for work on the land and in the factories. (3) A clean sweep of all officials of enemy blood or connections from Government departments. Stringent peace terms to include the dismemberment of the Hapsburg Empire." The party also supported: "equal pay for equal work, equal marriage and divorce laws, the same rights over children for both parents, equality of rights and opportunities in public service, and a system of maternity benefits." Christabel and Emmeline had now completely abandoned their earlier socialist beliefs and advocated policies such as the abolition of the trade unions.

After the passing of the Qualification of Women Act in 1918, Christabel became one of the seventeen women candidates that stood in the post-war election. Christabel Pankhurst represented the The Women's Party in Smethwick. Elsie Bowerman became her agent but despite the fact that the Conservative Party candidate agreed to stand down, she lost a straight fight with the representative of the Labour Party by 775 votes.

In 1922 Elsie Bowerman and Flora Drummond established the Women's Guild of Empire, a right wing league opposed to communism. Drummond's biographer, Krista Cowman, pointed out: "When the war ended she was one of the few former suffragettes who attempted to continue the popular, jingoistic campaigning which the WSPU had followed from 1914 to 1918. With Elsie Bowerman, another former suffragette, she founded the Women's Guild of Empire, an organization aimed at furthering a sense of patriotism in working-class women and defeating such socialist manifestations as strikes and lock-outs." By 1925 it was claimed the organization had a membership of 40,000. In April 1926, Bowerman and Drummond led a demonstration that demanded an end to the industrial unrest that was about to culminate in the General Strike.

Elsie Bowerman, a member of the Middle Temple, read for the bar, and became one of the first women barristers. According to Elizabeth Crawford: "She practised on the south-eastern circuit from 1928 until 1946, was involved with the Sussex sessions from 1928 until 1934, and wrote The Law of Child Protection (1933)."

In 1938, she joined forces with the Marchioness of Reading, to establish the Women's Voluntary Service, and from 1938 to 1940 edited its Monthly Bulletin. During the Second World War she worked for the Ministry of Information (1940–41) and was liaison officer with the North American Service of the BBC (1941–5). Elsie Bowerman suffered a stroke, and died at the Princess Alice Hospital, Eastbourne, on 18th October 1973.

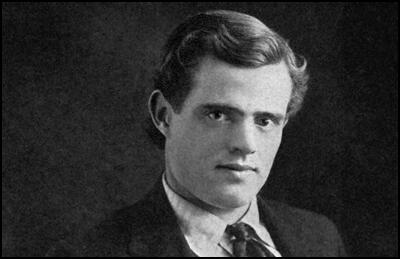

On this day in 1916 Jack London died. London was born in San Francisco on 12th January, 1876. His mother, Flora Wellman, was unmarried, but lived with William Chaney, an itinerant astrologer. Chaney left Flora soon after she became pregnant.

Jack London left school at fourteen because his family could not afford to put him through high school and he began work at Hickmott's, the local canning factory. London had a great love of books and he decided that he would now spend more time in Oakland Library. His reading included books by Rudyard Kipling, Gustave Flaubert, Leo Tolstoy and Herman Melville. London also began writing short-stories. When the San Francisco Morning Call announced a competition for young writers, the 17 year old London submitted Typhoon off the Coast of Japan. It won first prize of $25, with second and third prizes going to men in their early twenties studying at the University of California and at Stanford University.

London was also developing an interest in politics. He read about Eugene Debs being imprisoned for leading a rail-workers' strike in Chicago. He decided to join a march on Washington led by Jacob S. Coxley. The plan was to demand that Congress allocate funds to create jobs for the unemployed. In Oakland a young printer, Charles T. Kelly, assembled a detachment of two thousand men who would travel to the capital in box-cars provided free of charge by railroad companies anxious to shunt them east and thereby rid the region of potential trouble-makers. When the men reached Des Moines, Iowa, the railroad company decided the journey had come to an end.

At Oakland Library London found a copy of The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. He wrote in his notebook: "The whole history of mankind has been a history of contests between exploiting and exploited; a history of these class struggles shows the evolution of man; with the coming of industrialism and concentrated capital a stage has been reached whereby the exploited cannot attain its emancipation from the ruling class without once and for all emancipating society at large from all future exploitation, oppression, class distinctions and class struggles."

Jack London also read Looking Backward, a novel written by Edward Bellamy. Published in 1888 and set in Boston, the book's hero, Julian West, falls into a hypnotic sleep and wakes in the year 2000, to find he is living in a socialist utopia where people co-operate rather than compete. The novel was highly successful and sold over 1,000,000 copies. It was the third largest bestseller of its time, after Uncle Tom's Cabin and Ben-Hur and it is claimed that the book converted a large number of people to socialism.

Jack London wrote that he had "began a frantic pursuit of knowledge." London discovered that "other and greater minds, before I was born, had worked out all that I thought, and a vast deal more. I discovered that I was a Socialist." He joined the local Socialist Labor Party (SLP) in Oakland and made speeches on street-corners. On 16th February 1896, the San Francisco Chronicle reported: "Jack London, who is known as the boy socialist of Oakland, is holding forth nightly to the crowds that throng City Hall Park. There are other speakers in plenty, but London always gets the biggest crowd and the most respectful attention. the young man is a pleasant speaker, more earnest than eloquent, and while he is a broad socialist in every way, he is not an anarchist."

In July, 1897, Jack London read of gold being found in the Klondike region of the Yukon in north-western Canada. This created a "stampede of prospectors". London approached local newspapers with the idea of reporting on the Klondike Gold Rush. The idea was rejected but London was determined to go and after borrowing money from step-sister Eliza, he began making preparations to leave university.

It has been estimated that over $60 million was spent by prospectors during the Klondike Gold Rush but gold valued at $10 million was extracted from the ground. Jack London was one of those who arrived back home broke (he claimed he found only $4.50 in gold dust). However, the experience had provided him with some great experiences to write about: "I never realised a cent from any properties I had an interest in up there. Still, I have been managing to pan out a living ever since on the strength of the trip." (18)

Jack London was convinced that he now had the material for a successful writing career. As Alex Kershaw, the author of Jack London: A Life (1997) has pointed out: "Sheer discipline would be his lifeline. He would also adopt Kipling's work ethic. Work! Work! And so he established a routine, which was to last a lifetime of writing a thousand words a day. If he fell behind his daily quota, he compensated the following morning." (19)

However, his first stories that he produced were rejected by magazine publishers. It took him six months before the highly regarded Overland Monthly, accepted the first of Jack London's Klondike stories, To The Man on Trail. This was followed by The White Silence that appeared in the February 1899 edition. It received a great reviews and established London was one of the country's most promising writers. George Hamlin Fitch, literary critic of the San Francisco Chronicle, concluded: "I would rather have written The White Silence than anything that has appeared in fiction in the last ten years." (20) London was very disappointed that the magazine only paid him $7.50 for the story.

Jack London now sent his short-stories to Atlantic Monthly, the most important literary magazine in New York City. In January 1900 they paid him $120 for An Odyssey of the North. This brought him to the attention of the publishers Houghton Mifflin, who suggested the idea of collecting his Alaska tales in book form. The result was The Son of the Wolf, which appeared in April 1900. Cornelia Atwood Pratt gave the book a great review: "His work is as discriminating as it is powerful. It has grace as well as terseness, and it makes the reader hopeful that the days of the giants are not yet gone by."

Later that year Jack London won a short-story competition sponsored by Cosmopolitan. The magazine was so impressed that they offered him the post of assistant editor and staff writer. He rejected the idea of being employed by a magazine. He told his friend, Cloudesley Johns: "I shall not accept it. I do not wish to be bound... I want to be free, to write what delights me. No office work for me; no routine; no doing this set task and that set task. No man over me."

In 1901 he agreed to exploit his growing fame by becoming the socialist candidate for Mayor of Oakland.The San Francisco Evening Post reported on 26th January, 1901: "Jack London is announced as a candidate for Mayor of Oakland... I don't know what a socialist is, but if it is anything like some of Jack London's stories, it must be something awful. I understand that as soon as Jack London is elected Mayor of Oakland by the Social Democrats the name of the place will be changed. The Social Democrats, however, have not yet decided whether they will call it London or Jacktown." (29) London received just 246 votes (the winning candidate obtained 2,548). However, he was happy that he was able to bring the principles of socialism to a wider audience.

The New York City publisher, Samuel McClure offered to publish virtually anything Jack London produced. To obtain his services he agreed to pay him a retainer of $100. However, he was disappointed with his first novel, A Daughter of the Snows, and refused to serialize it in McClure's Magazine. McClure sold it to another publisher for $750 and it was published in 1902. Alex Kershaw argues that "A Daughter of the Snows was a badly executed jumble of his current intellectual confusions. Its disorganised melodrama and unconvincing characters failed to impress."

In July 1902 London moved to England where he worked with the Social Democratic Federation. He was shocked by the poverty he saw and began writing a book about slum life in London. He wrote a letter to the poet, George Sterling, about the proposed book: "How often I think of you, over there on the other side of the world! I have heard of God's country, but this country is the country God has forgotten he forget. I've read of misery, and seen a bit; but this beats anything I could even have imagined. Actually, I have seen things and looked the second time in order to convince myself that it really is so. This I know, the stuff I'm turning out will have to be expurgated or it will never see magazine publication... You will read some of my feeble efforts to describe it some day. I have my book over one-quarter done and am bowling along in a rush to finish it and get out of here. I think I should die if I had to live two years in the East End of London."

In his notes, he wrote "if I were God one hour, I'd blot out all London and its 6,000,000 people, as Sodom and Gomorrah were blotted out, and look upon my work and call it good." Alex Kershaw, the author of Jack London: A Life (1997) has pointed out: "He (Jack London) was exhausted and emotionally drained. He had studied pamphlets, books and government reports on poverty, interviewed scores of men and women, taken hundreds of photographs, tramped miles of streets, stood in breadlines, slept in parks. What he had seen had seared his soul. London was more brutal in its unrelenting misery than the Klondike.... What made Jack such an effective but controversial reporter was his personal involvement. His greatest strength was his passionate bias in favour of capitalism's victims. He knew their suffering because he had felt it himself. His critics had not. Throughout his stay in London, memories of his youth had returned. Only by reassuring himself that he had escaped the conditions of his childhood could he control his fear that he might one day return to them."

The People of the Abyss was published by Macmillan in 1903. It was a surprise success, selling over twenty thousand copies in America. It was not as well received in England. Charles Masterman, who lived in the East End, and was the author of From the Abysss (1902) wrote in The Daily News: "Jack London has written of the East End of London as he wrote of the Klondike, with the same tortured phrase, vehemence of denunciation, splashes of colour, and ferocity of epithet. He has studied it 'earnestly and dispassionately' - in two months! It is all very pleasant, very American, and very young."

Jack London decided to write a novella about a dog named Buck who is a working dog during the Klondike Gold Rush. It was first published in four installments in The Saturday Evening Post, who bought it for $750. George Platt Brett of Macmillan offered to publish it as a book. He asked London to "remove the few instances of profanity in the story, because, in addition to the grown-up audience for the book, there is undoubtedly a very considerable school audience". He agreed to pay $2,000 for the story: "I like the story very well indeed, although I am afraid it is too true to nature and too good work to be really popular with the sentimentalist public."

The Call of the Wild was published in July 1903. It received extremely good reviews and critics hailed it as a "classic enriching American literature", "a spellbinding animal story", "a brilliant dramatisation of the laws of nature". The literary magazine, the Criterion, described it as: "The most virile, freshly conceived, dramatically told, and firmly sustained book of the season is unquestionably Jack London's Call of the Wild... Such books as these clarify the literary atmosphere and give a new, clean vibrant breath in a depression of romances and problems; they act like an invigorating wind from the open sea upon the dullness of a sultry day."

It was an immediate best-seller. The first edition of 10,000 copies sold out in 24 hours. Unfortunately for London, he had sold the rights of the book to his publisher for a flat fee of $2,000. Richard O'Connor, the author of Jack London: A Biography (1964), has argued that the novel was as good as anything Rudyard Kipling had written and had finally "struck the chord that awakened the fullest response" in American readers.

London remained active in politics and was a member of the American Socialist Party. In 1905 he joined with Upton Sinclair to form the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Other members included Norman Thomas, Clarence Darrow, Florence Kelley, Anna Strunsky, Randolph Bourne, Bertram D. Wolfe, Jay Lovestone, Rose Pastor Stokes and J.G. Phelps Stokes. Its stated purpose was to "throw light on the world-wide movement of industrial democracy known as socialism."

Jack London followed The Call of the Wild with The Sea-Wolf (1904), The War of the Classes (1905), The Iron Heel (1907) and Martin Eden (1909), a book that sold a quarter of a million copies within a couple of months of being published in the United States. London, a heavy drinker, wrote about the problems of alcohol in his semi-autobiographical novel, John Barleycorn (1913). This was then used by the Women's Christian Temperance Union in its campaign for prohibition.

With his royalties London bought a 1,400 acre ranch. He told one interviewer that he was still a socialist but: "I've done my part, Socialism has cost me hundreds of thousands of dollars. When the time comes I'm going to stay right on my ranch and let the revolution go to blazes."

London, was disappointed by the failure of the socialist movement to prevent the First World War that began in 1914. However, unlike most members of the American Socialist Party, London did not favour the United States remaining neutral. London, who was proud of his English heritage, was a strong supporter of the Allies against the Central Powers.

In September 1914 London agreed to write a propaganda article for a book being published in protest against the German invasion of Belgium. London's anti-German feelings were revealled in his comments to his wife that: "Germany has no honour, no chivalry, no mercy. Germany is a bad sportsman. German's fight like wolves in a pack, and without initiative of resource if compelled to fight singly."

London received support from Upton Sinclair and William English Walling, but felt isolated by his opinions on the war. He was also angry about how some fellow socialists had attacked him for spending so much money on his ranch. In March, 1916, London resigned from the party claiming that the reason was its "lack of fire and fight".

Floyd Dell complained that London had lost his faith in socialism: "A few years earlier, sent to Mexico as a correspondent, he came back singing the tunes that had been taught him by the American oil-men who were engaged in looting Mexico; he preached Nordic supremacy, and the manifest destiny of the American exploiters. He had, apparently, lost faith in the revolution in which he had once believed."

In October 1916 London urged Theodore Roosevelt to run for president against Woodrow Wilson. However, he told the New York World that although he supported Roosevelt "nobody in this fat land will vote (for him) because he exalts honour and manhood over the cowardice and peace-lovingness of the worshipers of fat."

London's health deteriorated rapidly in 1916. He was suffering from uraemia, a condition that impairs the functioning of the kidneys. On 21st November, 1916, Jack London died from a morphine overdose. From the available evidence it is not clear whether this was an accident or suicide.

Floyd Dell later recalled: "His death, as a tired cynic, to whom life no longer was worth living - according to the accounts of his friends - was a miserable anti-climax. But he died too early. If he had lived a little longer, he would have seen the Russian Revolution. Life would have had some meaning for him again. He would have had something in his own vein to write about. And he might have died with honor."

On this day in 1962 Mabel Tuke, died of cerebral thrombosis in Ashbrooke Nursing Home, 12 St John's Road, Nevilles Cross, Durham,

Mabel Lear, he eldest of three daughters, of Richard Lear (1834–1894), was born at Plumstead on 19th May 1871. Her father was clerk of works in the Royal Engineers Department.

The family moved to Lichfield and on 25th February 1895 she married James Quarton Braidwood, a gas engineer. As her biographer, Elizabeth Crawford, has pointed out: "Nothing can be traced of the fate of this marriage; it was presumably ended, possibly in South Africa, by the death of her husband. In 1901 she married, probably in South Africa, George Moxley Tuke, a captain in the South African constabulary." After her husband's early death she returned in 1905 to England. On the boat from South Africa she met Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, who told her about the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU).

Mabel Tuke joined the WSPU and in 1906 she became the organisation's honorary secretary based at Clement's Inn. She was especially close to Christabel Pankhurst and Emmeline Pankhurst. As Elizabeth Crawford pointed out: "She was affectionately known as Pansy, a nickname obviously inspired by her luminous dark eyes. Beautiful, soft, and appealing, she represented the womanly image that the Pankhursts were keen to promote in order to counteract the popular conception of the suffragettes."

On 1st March 1912 she was arrested for breaking a window in 10 Downing Street. She was found guilty and received a three weeks sentence in Holloway Prison. While she was in prison she was charged with conspiracy. However, these charges were dropped.

After leaving prison Mabel Tuke was in such poor health she returned to South Africa. In the summer of 1913 she was living with Christabel Pankhurst in Paris.

According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999): In 1925 Mabel Tuke took part with Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst, in the ill-fated scheme to run a tea-shop at Jules-les-Pins on the French Riviera. Mrs Tuke provided most of the capital and did the baking." The venture was unsuccessful and they returned to England in the spring of 1926.

Mabel Tuke died of cerebral thrombosis in Ashbrooke Nursing Home, 12 St John's Road, Nevilles Cross, Durham, on 22 November 1962.

On this day in 1963 John F. Kennedy is assassinated. On 10th June, 1963, Kennedy gave a speech at the American University that included the following passage: "Today the expenditure of billions of dollars every year on weapons acquired for the purpose of making sure we never need them is essential to the keeping of peace. But surely the acquisition of such idle stockpiles - which can only destroy and never create - is not the only, much less the most efficient, means of assuring peace. I speak of peace, therefore, as the necessary, rational end of rational men. I realize the pursuit of peace is not as dramatic as the pursuit of war, and frequently the words of the pursuers fall on deaf ears. But we have no more urgent task. Some say that it is useless to speak of peace or world law or world disarmament, and that it will be useless until the leaders of the Soviet Union adopt a more enlightened attitude. I hope they do. I believe we can help them do it. But I also believe that we must reexamine our own attitudes, as individuals and as a Nation, for our attitude is as essential as theirs. And every graduate of this school, every thoughtful citizen who despairs of war and wishes to bring peace, should begin by looking inward, by examining his own attitude towards the possibilities of peace, towards the Soviet Union, towards the course of the cold war and towards freedom and peace here at home."

However, as James W. Douglass has pointed out in JFK and the Unspeakable (2008): “Only nine days after his American University address, Kennedy had ratified a CIA program contradicting it. Kennedy’s regression can be understood in the political context of the time. He was, after all, an American politician, and the Cold War was far from over. For the remaining five months of his life, John Kennedy continued a policy of sabotage against Cuba that he may have seen as a bone thrown to his barking CIA and military advisers but was in any case a crime against international law. It was also a violation of the international trust that he and Nikita Khrushchev had envisioned and increasingly fostered since the missile crisis. Right up to his death, Kennedy remained in some ways a Cold Warrior, in conflict with his own soaring vision in the American University address.”

On 22nd November, 1963, President John F. Kennedy arrived in Dallas. It was decided that Kennedy and his party, including his wife, Jacqueline Kennedy, Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, Governor John Connally and Senator Ralph Yarborough, would travel in a procession of cars through the business district of Dallas. A pilot car and several motorcycles rode ahead of the presidential limousine. As well as Kennedy the limousine included his wife, John Connally, his wife Nellie, Roy Kellerman, head of the Secret Service at the White House and the driver, William Greer. The next car carried eight Secret Service Agents. This was followed by a car containing Lyndon Johnson and Ralph Yarborough.

At about 12.30 p.m. the presidential limousine entered Elm Street. Soon afterwards shots rang out. John Kennedy was hit by bullets that hit him in the head and the left shoulder. Another bullet hit John Connally in the back. Ten seconds after the first shots had been fired the president's car accelerated off at high speed towards Parkland Memorial Hospital. Both men were carried into separate emergency rooms. Connally had wounds to his back, chest, wrist and thigh. Kennedy's injuries were far more serious. He had a massive wound to the head and at 1 p.m. he was declared dead.

Within two hours of the killing, a suspect, Lee Harvey Oswald, was arrested. Throughout the the time Oswald was in custody, he stuck to his story that he had not been involved in the assassination. On 24th November, while being transported by the Dallas police from the city to the county jail, Oswald was shot dead by Jack Ruby.

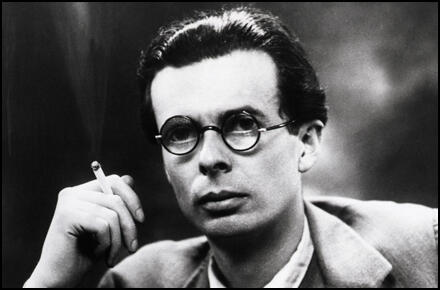

On this day in 1963 Aldous Huxley died. Huxley, the third son of Leonard Huxley, a teacher at Charterhouse School and subsequently editor of The Cornhill Magazine, was born in Godalming on 26th July 1894.

His mother, Julia Frances Huxley, was the daughter of Thomas Arnold (1823–1900) and the granddaughter of Thomas Arnold (1795–1842) of Rugby School. His grandfather was T. H. Huxley and his aunt was Mary Humphry Ward. His eldest brother was Julian Huxley.

Huxley attended Prior's Field, a progressive school founded by his mother. He arrived at Eton College in the autumn 1908. Soon afterwards his mother died that according to one biographer, destroyed his faith in life. In 1911 Huxley was struck down by a staphylococcic infection in the eye that left him purblind for eighteen months. According to David King Dunaway: "At home Huxley taught himself to read Braille, to touch-type, and to play the piano. His eyesight improved to one-quarter of normal vision in one eye (he spent half a century experimenting with alternative therapies and surgery)."

Huxley won a scholarship to Balliol College, to read English language and literature. However, he could only study by dilating his eyes with drops and using a large magnifying glass. While at Oxford University Huxley contributed articles to The Athenaeum. This brought him into contact with John Middleton Murry who introduced him to writers such as D. H. Lawrence and Katherine Mansfield.

Aldous Huxley began spending time with Philip Morrell and Ottoline Morrell at their home Garsington Manor near Oxford. It was also a refuge for conscientious objectors. They worked on the property's farm as a way of escaping prosecution. It also became a meeting place for a group of intellectuals described as the Bloomsbury Group. Members included Virginia Woolf, Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell, John Maynard Keynes, David Garnett, E. M. Forster, Duncan Grant, Lytton Strachey, Dora Carrington, Gerald Brenan, Ralph Partridge, Bertram Russell, Leonard Woolf, Desmond MacCarthy and Arthur Waley. Other people who Huxley met at Garsington included Dorothy Brett, Mark Gertler, Siegfried Sassoon, Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, Thomas Hardy, Vita Sackville-West, Harold Nicolson and T.S. Eliot.

One of the members of this group, Frances Partridge, later recalled in her autobiography, Memories (1981): "They were not a group, but a number of very different individuals, who shared certain attitudes to life, and happened to be friends or lovers. To say they were unconventional suggests deliberate flouting of rules; it was rather that they were quite uninterested in conventions, but passionately in ideas. Generally speaking they were left-wing, atheists, pacifists in the First World War, lovers of the arts and travel, avid readers, Francophiles. Apart from the various occupations such as writing, painting, economics, which they pursued with dedication, what they enjoyed most was talk - talk of every description, from the most abstract to the most hilariously ribald and profane."

Leonard Woolf first met Huxley at Garsington Manor. He later commented: "The Oxford generations of the nineteen tens and nineteen twenties produced a remarkable constellation of stars of the first magnitude and I much enjoyed seeing them twinkle in the Garsington garden. There for the first time I saw the young Aldous Huxley folding his long, grasshopper legs into a deckchair and listened entranced to a conversation which is unlike that of any other person that I have talked with. I could never grow tired of listening to the curious erudition, intense speculative curiosity, deep intelligence which, directed by a gentle wit and charming character, made conversation an art."

Aldous Huxley fell in love with Dora Carrington during this period. "Her short hair, clipped like a page's, hung in a bell of elastic gold about her cheeks. She had large blue china eyes, whose expression was one of ingenuous and often puzzled earnestness." Although she enjoyed his company she was not looking for a physical relationship with Huxley. He told Dorothy Brett: "Carrington and I had a long argument on the subject of virginity: I may say it was she who provoked it by saying that she intended to remain a vestal for the rest of her life. All expostulations on my part were in vain."

After obtaining a first at Oxford University, Huxley taught at Repton School and at Eton College, where among his students were George Orwell and Harold Acton. He also published four volumes of poetry: The Burning Wheel (1916), Jonah (1917), The Defeat of Youth (1918), and Leda (1920). Lytton Strachey liked Huxley's poetry but claimed that "he looked like a piece of seaweed" but he was "incredibly cultured."

Aldous Huxley married, Maria Nys, a Belgian refugee who he had met at Garsington Manor, on 10th July 1919. The following year she gave birth to a son, Matthew (April 1920). They lived in a small flat in Hampstead, and as well as contributing to literary journals he began work on his first novel, Crome Yellow (1921). Scott Fitzgerald wrote that the novel was "the highest point so far attained by Anglo-Saxon sophistication" and that Huxley was "the wittiest man now writing in English".

Crome Yellow brought Huxley instant fame but upset his friends who appeared in the novel. This included Dora Carrington (Mary Bracegirdle). In the novel Huxley recreated his many discussions with Carrington. She explained what she was looking for in a man: "It must be somebody intelligent, somebody with intellectual interests that I can share. And it must be somebody with a proper respect for women, somebody who's prepared to talk seriously about his work and his ideas and about my work and my ideas. It isn't, as you see, at all easy to find the right person."

Ottoline Morrell felt betrayed by Huxley for writing about her in Crome Yellow. The character, Priscilla Wimbush, was described as having a "large square middle-aged face, with a massive projecting nose and little greenish eyes, the whole surmounted by a lofty and elaborate coiffure of a curiously improbable shade of orange." Ottoline was also furious about his rude and unfunny descriptions of her friends, Dorothy Brett, Dora Carrington, Bertram Russell and Mark Gertler. She told Huxley that his book reminded her of "poor photography".

Huxley followed Crome Yellow with Antic Hay (1923) and Those Barren Leaves (1925). According to David King Dunaway, all three novels "satirized social behaviour in post-war Britain using friends and family as fodder for incisive characterizations... The comic lightness of the novels was undermined by much wider social concerns.... Moreover, a dark thread runs through Huxley's musings on corruption in the smart set; his characters are torn between pleasures of the flesh and an austere dedication to the spirit, and Huxley was willing to expose human frailty, to illuminate hypocrisy."

Huxley continued the idea of writing about people he knew in his next novel, Point Counter Point (1928). Characters in this novel included Lucy Tantamount (Nancy Cunard), John Bidlake (Augustus John), Everard Webley (Oswald Mosley), Mark Rampion (D. H. Lawrence), Mary Rampion (Frieda Lawrence), Denis Burlap (John Middleton Murry) and Beatrice Gilray (Katherine Mansfield).

Beatrice Webb praised the writing of Huxley but disliked the subject matter of his books. She put in him the same group as D. H. Lawrence, Compton MacKenzie, David Garnett and Norman Douglas: "clever novelists... all depicting men and women as mere animals, and morbid at that. except always that these bipeds practise birth control and commit suicide. so it looks as if the species would happily die out. it is an ugly and tiresome idol of the mind, but it lends itself to a certain type of fantastic wit and stylish irony.

Huxley's books sold very well and with his royalties he purchased a villa in Bandol on the south coast of France. He also had a summer home at Forte dei Marmi in Tuscany. After the death of his friend, D. H. Lawrence, Huxley arranged for the publication of The Letters of D. H. Lawrence (1932). As well as novels, plays and short stories, Huxley wrote a large number of articles for newspapers and magazines.

In summer 1932 Huxley published Brave New World. It was an international best-seller and established him as Britain's best-known novelist between the wars. Translated into twenty-eight languages, the novel was inspired by Men Like Gods, a utopian novel by H. G. Wells. However, George Orwell argued that the novel "must be partly derived from" We by the Russian writer, Yevgeny Zamyatin. Huxley denied that he had ever heard of this book.

David King Dunaway has pointed out: "The novel, the first about human cloning, is a dystopia set five centuries in the future, when overpopulation has led to biogenetic engineering. Through computerized genetic selection, social engineers create a population happy with its lot. All the earth's children are born in hatcheries, and Soma, a get-happy pill, irons out most problems."

Time Magazine saw it as an attack on the culture of the United States with Henry Ford as the new God (worshippers say "Our Ford" instead of "Our Lord"): "Huxley's 1932 work - about a drugged, dull and mass-produced society of the future - has been challenged for its themes of sexuality, drugs and suicide. The book parodies H.G. Wells' utopian novel Men Like Gods and expresses Huxley's disdain for the youth and market-driven culture of the U.S. Chewing gum, then as now a symbol of America's teenybopper shoppers, appears in the book as a way to deliver sex hormones and subdue anxious adults; pornographic films called feelies are also popular grown-up pacifiers."

Beatrice Webb was also highly critical of the book: "I have been reading Aldous Huxley's Point Counter Point, and pondering over this strangely pathological writing, pathological without knowing it. The febrile futility of the particular clique he describes reminds me of that far more powerful book The Magic Mountain, by Thomas Mann. Far more powerful because Mann is describing a society of sick people ... Huxley's group do not know that they are sick and are presented as a sample of normal human life. What with their continuous and promiscuous copulations, their shallow talk and chronic idleness, the impression left is one of simple disgust at their bodies and minds.... And the book, apart from arousing a morbid interest in morbidity, is dull, dull, dull. In a few years' time it will be unreadable - it represents a fashion. In this characteristic of fashionableness Aldous Huxley is like his maternal aunt, Mrs Humphry Ward; also in his tendency to preach."

Aldous Huxley's next novel was Eyeless in Gaza (1936). Huxley then suffered from "writer's block" and it was several years before he could complete another novel. In 1937 Aldous and Maria Huxley travelled to North America, spending time in New York City and San Cristobal, where he finished, Ends and Means (1937), a book explaining his pacifist beliefs.

In January 1938 the Huxleys moved to California and was employed by Hollywood film studios. He wrote the screenplays for Pride and Prejudice (1940), Madame Curie (1943), Jane Eyre (1943), A Woman's Vengeance (1948), Prelude to Fame (1950) and Alice in Wonderland (1951). He found working with studio executives difficult who he described as having "the characteristics of the minds of chimpanzees".

Huxley's next book, The Devils of Loudun (1952), was "a historical recreation of a story of demonically possessed French nuns and exorcists". Based on the true events in the small French town of Loudun in 1631, it features the activities of Father Urbain Grandier. As Time Magazine pointed out: "In The Devils of Loudun, Aldous Huxley with skill and scholarship resurrects one of the forgotten scandals of Christendom. The result is a brilliantly quarrelsome tract that is also one of the most fascinating historical narratives of the year."