On this day on 15th February

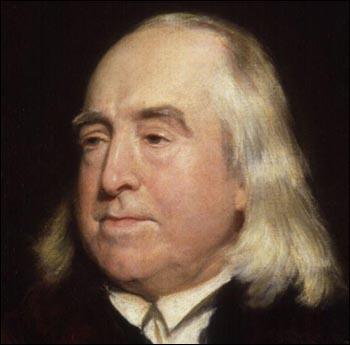

On this day in 1748 Jeremy Bentham, the son of a lawyer, was born in London. A brilliant scholar, Bentham entered Queen's College, Oxford at twelve and was admitted to Lincoln's Inn at the age of fifteen. Bentham was a shy man who did not enjoy making public speeches. He therefore decided to leave Lincoln Inn and concentrate on writing. Provided with £90 a year by his father, Bentham produced a series of books on philosophy, economics and politics.

Bentham's family had been Tories and for the first period of his life he shared their conservative political views. This changed after Bentham read the work of Joseph Priestley. One statement in particular from The First Principles of Government and the Nature of Political, Civil and Religious Liberty (1768) had a major impact on Bentham: "The good and happiness of the members, that is the majority of the members of the state, is the great standard by which every thing relating to that state must finally be determined."

Another important influence on Bentham was the philosopher David Hume. In books such as A Fragment on Government (1776) and Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (1789), Bentham argued that the proper objective of all conduct and legislation is "the greatest happiness of the greatest number". According to Bentham, "pain and pleasure are the sovereign masters governing man's conduct". As the motive of an act is always based on self-interest, it is the business of law and education to make the sanctions sufficiently painful in order to persuade the individual to subordinate his own happiness to that of the community.

In 1798 Bentham wrote Principles of International Law where he argued that universal peace could only be obtained by first achieving European Unity. He hoped that some form of European Parliament would be able to enforce the liberty of the press, free trade, the abandonment of all colonies and a reduction in the money being spent on armaments.

In Catechism of Reformers (1809) Bentham criticised the law of libel as he believed it was so ambiguous that judges were able to use it in the interests of the government. Bentham pointed out that the authorities could use the law to punish any Radical for "hurting the feelings" of the ruling class. Bentham also attacked other aspects of the legal system such as "jury packing".

Radical reformers such as Sir Francis Burdett, Leigh Hunt, William Cobbett, and Henry Brougham praised Bentham's work. Although written in a complex style, radical publishers attempted to communicate his ideas to the working class. Thomas Wooler published extracts in his journal Black Dwarf and eventually published a cheap edition of Catechism of Reformers. When Burdett introduced a series of resolutions in the House of Commons in July 1818, demanding universal suffrage, annual parliaments and vote by ballot, he quoted the writings of Jeremy Bentham to support his case.

In 1824 Bentham joined with James Mill (1773-1836) to found the Westminster Review, the journal of the philosophical radicals. Contributors to the journal included Lord Byron, Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Thomas Carlyle.

Bentham's most detailed account of his ideas on political democracy appeared in his book Constitutional Code (1830). In the book Bentham argued that political reform should be dictated by the principal that the new system will promote the happiness of the majority of the people affected by it. Bentham argued in favour of universal suffrage, annual parliaments and vote by ballot. According to Bentham there should be no king, no House of Lords, no established church. The book also included Bentham's view that women, as well as men, should be given the vote.

In Constitutional Code Bentham also addressed the problem of how government should be organised. For example, he suggested the introduction of rules that would ensure the regular attendance of members of the House of Commons. Government officials should be selected by competitive examination. The book also suggested the continual inspection of the work of politicians and government officials. Bentham pointed out they should be continually reminded that they are the "servants, not the masters, of the public".

Jeremy Bentham died on 6th June 1832.

Jeremy Bentham

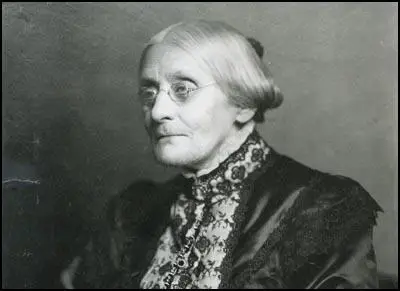

On this day in 1820 Susan Brownhill Anthony, the daughter of Daniel Anthony, a cotton manufacturer, was born in Adams, Massachusetts, on 15th February, 1820. Her father was a Quaker who campaigned against the slave trade.

After an education at her father's school and a Philadelphia boarding school, she began teaching at a female academy near Rochester, New York.

In 1852 Anthony joined with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Amelia Bloomer in campaigning for women's suffrage and equal pay. Anthony also became involved in the campaign for prohibition and was active in the American Anti-Slavery Society and helped escaped slaves on the Underground Railroad.

During the American Civil War Anthony strongly supported the Union cause. She also aided the administration of President Abraham Lincoln by forming the Women's Loyal League. In 1866 Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott and Lucy Stone established the American Equal Rights Association. The following year, the organisation became active in Kansas where Negro suffrage and women's suffrage was to be decided by popular vote. However, both ideas were rejected at the polls. In 1868 Anthony and Stanton founded the political weekly, The Revolution.

In 1869 Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton formed a new organisation, the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). The organisation condemned the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments as blatant injustices to women. The NWSA also advocated easier divorce and an end to discrimination in employment and pay. Anthony toured the country making speeches on women's rights. In one year alone, she travelled 13,000 miles and made over 170 speeches. In 1872 Anthony attempted to vote in a an election in Rochester. She was arrested, charged and later found guilty of violating voting rights.

Another group, the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), was also active in the campaign for women's rights and by the 1880s it became clear that it was not a good idea to have two rival groups campaigning for votes for women. After several years of negotiations, the AWSA and the NWSA merged in 1890 to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Elizabeth Cady Stanton became the NAWSA's first president, but Anthony took over in 1892 and held the post for the next eight years.

Anthony was also a historian and with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Matilda Joslyn Gage, she complied and published the four volume, The History of Woman Suffrage (1881-1902).

Susan B. Anthony died on 13th March, 1906.

On this day in 1835 Henry 'Orator' Hunt died of a stroke at his home in Whitchurch, Hampshire. Hunt, the son of Thomas Hunt, a gentleman farmer, was born in Upavon, on 6th November 1773. After ten years education at the local grammar school, Henry joined his father in looking after the family estates. When Thomas Hunt died in 1797, Henry became the owner of 3,000 acres in Wiltshire as well as a large estate in Somerset. Henry married and during the next few years his wife gave birth to three children.

In 1800 Henry Hunt became involved in a dispute with Lord Bruce, a colonel in the Wiltshire Yeomanry over the killing of some pheasants. Lord Bruce took Hunt to court over the matter. Hunt was found guilty and sentenced to six weeks imprisonment. During his court case, Hunt met Henry Clifford, a radical lawyer who was involved in the campaign for adult suffrage. Clifford introduced Hunt to several of his political friends, including Francis Place, Thomas Hardy and Horne Tooke.

Hunt now became involved in radical politics. This brought him into conflict with local landowners and in 1810 Hunt moved to a new 20,000 acre estates at Worth, near East Grinstead. While living at Rowfant House, Hunt became more active in politics. Hunt had by now achieved a reputation as a magnificent orator and was constantly being asked to speak at public meetings. In 1816 Henry 'Orator' Hunt spoke at large reform meetings at Birmingham (80,000), Blackburn (40,000), Nottingham (20,000), Stockport (20,000) and Macclesfield (10,000).

Samuel Bamford met him at one of these meeetings: "Henry Hunt was a gentlemanly in his manner and attire, six feet and better in height, and extremely well formed. He was dressed in a blue lapelled coat, light waistcoat and kerseys, and topped boots. He wore his own hair; it was in moderate quantity and a little grey. His lips were delicately thin and receding. His eyes were blue or light grey - not very clear nor quick, but rather heavy; except as I afterwards had opportunities for observing, when he was excited in speaking; at which times they seemed to distend and protrude; and if he worked himself furious, as he sometimes would, they became blood-streaked, and almost started from their sockets. His voice was bellowing; his face swollen and flushed; his griped hand beat as if it were to pulverise; and his whole manner gave token of a painful energy."

In 1818 Henry Hunt was selected as the radical candidate for the Westminster constituency. In his campaign Hunt advocated annual parliaments, universal suffrage, the secret ballot and the repeal of the Corn Laws. Although popular with the large crowds that attended his meetings, he was deeply disliked by the majority of the electorate and Hunt won only 84 votes.

On 16th August 1819, Henry 'Orator' Hunt and Richard Carlile spoke at a meeting of 80,000 people on parliamentary reform at St. Peter's Fields in Manchester. The local magistrates ordered the yeomanry (part-time cavalry) to break up the meeting. Just as Henry Hunt was about to speak, the yeomanry charged the crowd and in the process killed eleven people. Afterwards, this event became known as the Peterloo Massacre. Hunt, Samuel Bradford and eight other leaders of the movement were arrested and charged with holding an "unlawful and seditious assembling for the purpose of exciting discontent". Hunt was found guilty and sentenced to two and a half years imprisonment in Ilchester Gaol. While in prison Hunt wrote his Memoirs where he attempted to explain why he had become a radical reformer.

After he was released in October 1822, Hunt returned to his campaign for adult suffrage. With the help of his friend, William Cobbett, Hunt formed the Radical Reform Association. In 1826 he unsuccessfully stood for Somerset but it 1830 he was selected as the radical candidate for Preston, one of the few towns in England that had given the vote to all males who paid taxes.

As well as campaigning for parliamentary reform, Henry 'Orator' Hunt addressed the other issues that concerned the working class people living in a town which employed over 10,000 people in the textile insustry. This included their desire for a ten hour day and an end to child labour. Henry Hunt complained about the way his campaign was reported in the local newspapers: "I have personally visited the factories, and witnessed the sufferings of the overworked children. but, my friends, you never heard of this. No, no, my speeches on the subject were all suppressed by the press."

When the election was held Henry Hunt successfully defeated Edward Stanley, the chief secretary for Ireland in the Whig government by 3,750 votes to 3,392. After his victory, Hunt and an estimated crowd of 16,000 people, marched to Manchester and held a meeting at the site of the Peterloo Massacre.

In the House of Commons, Hunt spoke often on the subject of radical reform. However, Hunt was opposed to the 1832 Reform Act as it did not grant the vote to working class males. Instead he proposed what he called the Preston-type of universal suffrage, "a franchise which excluded all paupers and criminals but otherwise recognized the principle of an equality of political rights that all who paid taxes should have the vote." Some radicals disagreed with Hunt and argued that he should support any attempt to extend the franchise.

Hunt's decision not to support the 1832 Reform Act upset some radicals in Preston and in the 1833 General Election, Henry Hunt was defeated. After the election Henry Hunt told his supporters: "I have done everything in my power to maintain, uphold, and secure your rights, but I have failed upon this occasion. I shall retire into private life with the reflection, that I have never, upon any occasion, flinched from performing my duty to you, and the whole of the working classes of the United Kingdom."

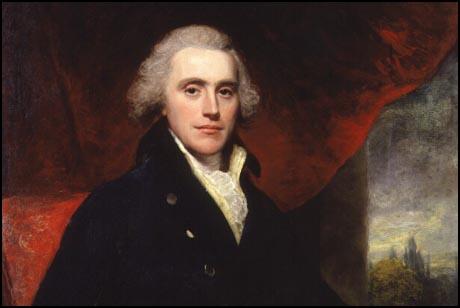

On this day in 1844 Henry Addington, Lord Sidmouth, died. Addington was born in 1759. Henry's father, Dr. Anthony Addington, had several important patients including the prime minister, Lord Chatham and his son, William Pitt. After being educated at Winchester School and Oxford University he became a lawyer.

Addington's friendship with the Pitt family helped him obtain the seat for Devizes in 1784. Later that year, William Pitt, like his father before him, became prime minister of Britain. Henry Addington was a loyal supporter of Pitt's Tory administration. Although Addington was only thirty, in 1789 Pitt suggested that he should become speaker of the House of Commons. Addington agreed with the proposal and with the help of Pitt was elected as speaker. The post received a salary of £6,000 a year and this enabled Addington to purchase a large estate in Reading.

William Pitt's policy of Catholic Emancipation so upset King George III that he asked Addington to help him remove his prime minister. After discussing the matter with William Pitt, Addington agreed, and in 1801 he became Britain's new prime minister. Several ministers such as George Canning and Lord Castlereagh who agreed with Pitt's policy on Catholics, refused to serve under Addington. Henry Addington was an unpopular prime minister and in 1804 large numbers of his own party turned against him and he decided to resign.

The following year Addington was granted the title of Lord Sidmouth and agreed to serve as a minister in Pitt's government. However, he only served under William Pitt for six months. When Pitt refused to promote Viscount Sidmouth's friends he resigned from the cabinet.

In 1812 Lord Liverpool became prime minister and he offered Sidmouth the post of Home Secretary in his new government. Viscount Sidmouth now had the responsibility of dealing with social unrest in Britain. This included making machine-breaking an offence punishable by death. On one day alone, fourteen Luddites were executed in York. Social unrest continued and in 1817, Sidmouth was responsible for the passing of what became known as the Gagging Acts. This resulted in the arrest and imprisonment of radical journalists such as Richard Carlile.

The unpopularity of Sidmouth increased in 1819 after he wrote a letter supporting the action of the magistrates and the Manchester & Salford Yeomanry at what opponents called the Peterloo Massacre. In November 1819, Sidmouth persuaded Parliament to pass a series of repressive measures that became known as the Six Acts. Sidmouth retired from office in 1821. He continued to support the Tories in parliament and voted against Catholic Emancipation in 1829 and the Reform Act of 1832.

On this day in 1844 Thomas Hawksley is interviewed by a Parliamentary Committee. Nottingham became one of the first towns in Britain to pipe fresh water into all homes. Hawksley was appointed as chief engineer and in 1844 he told Parliament about his work: "Before the supply was laid on in the houses water was sold chiefly to the labouring-classes by carriers at the rate of one farthing a bucket; and if the water had to be carried any distance up a court a halfpenny a bucket was, in some instances, charged. In general it was sold at about three gallons for a farthing. But the Company now delivers to all the town 76,000 gallons for £1; in other words, carries into every house 79 gallons for a farthing, and delivers water night and day, at every instant of time that it is wanted, at a charge 26 times less than the old delivery by hand."

In 1847 the British government proposed a Public Health Bill that was based on some of the recommendations of Edwin Chadwick. There were still a large number of MPs who were strong supporters of what was known as laissez-faire. This was a belief that government should not interfere in the free market. They argued that it was up to individuals to decide on what goods or services they wanted to buy. These included spending on such things as sewage removal and water supplies. George Hudson, the Conservative Party MP, stated in the House of Commons: "The people want to be left to manage their own affairs; they do not want Parliament... interfering in everybody's business."

Supporters of Chadwick argued that many people were not well-informed enough to make good decisions on these matters. Other MPs pointed out that many people could not afford the cost of these services and therefore needed the help of the government. The Health of Towns Association, an organisation formed by doctors, began a propaganda campaign in favour of reform and encouraged people to sign a petition in favour of the Public Health Bill. In June 1847, the association sent Parliament a petition that contained over 32,000 signatures. However, this was not enough to persuade Parliament, and in July the bill was defeated.

A few weeks later news reached Britain of an outbreak of cholera in Egypt. The disease gradually spread west, and by early 1848 it had arrived in Europe. The previous outbreak of the disease in Britain in 1831, had resulted in the deaths of over 16,000 people. Faced with the possibility of a cholera epidemic, the government decided to try again. This new bill involved the setting up of a Board of Health Act, that had the power to advise and assist towns which wanted to improve public sanitation.

In an attempt to persuade the supporters of laissez-faire to agree to a Public Health Act, the government made several changes to the bill introduced in 1847. For example, local boards of health could only be established when more than one-tenth of the ratepayers agreed to it or if the death-rate was higher than 23 per 1000. Chadwick was disappointed by the changes that had taken place, but he agreed to become one of the three members of the central Board of Health when the act was passed in the summer of 1848. However, the act was passed too late to stop the outbreak of cholera that arrived in Britain that September. In the next few months, cholera killed 80,000 people. Once again, it was mainly the people living in the industrial slums who caught the disease.

By 1853 over 160 towns and cities had set up local boards of health. Some of these boards did extremely good work and were able to introduce important reforms. Thomas Hawksley, for example, after his success in Nottingham, was appointed to many major water supply projects across England, including schemes for Liverpool, Sheffield, Leicester, Leeds, Derby, Oxford, Cambridge, Sunderland, Lincoln, Darlington, Wakefield and Northampton.

Thomas Hawksley was consulted in 1857 about the London main drainage scheme. Hawksley was also involved in the building of the Thornton Park Reservoir (1860), Dale Dike Reservoir (1864), Bradgate Reservoir (1868) and Waskerley Reservoir (1872). He was also president of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers in 1876–7, and became a fellow of the Royal Society in 1878.

Thomas Hawksley died on 23rd September 1893 at his home, 14 Phillimore Gardens, Kensington, at the age of eighty-six.

On this day in 1883 Fritz Gerlich, the eldest of the three sons of wholesale and retail fishmonger Paul Gerlich and his wife Therese, was born in Stettin, Germany. After attending the Marienstiftungymnasium, before arriving at the University of Munich in 1902.

Gerlich began studying natural sciences but shifted to history, receiving a doctorate for a dissertation on an eleventh-century Germanic emperor. After leaving university, Gerlich worked in the state archives. He held conservative views and published several anti-socialist articles in the right-wing press.

As a result of his poor eyesight, Gerlich was unable to join the German Army during the First World War. He became a strong opponent of the Russian Revolution and in 1917 joined Alfred von Tirpitz, Wolfgang Kapp and Anton Drexler to form the German Fatherland Party. Gerlich published the book Communism as the Theory of the Thousand Year Reich (1919). In the book he denounced anti-Semitism, which he believed had grown worse because of the leading role that Jews had taken in the revolution.

In 1920 Gerlich was appointed as editor in chief of the Münchner Neueste Nachrichten. Over the next couple of years he emerged as a respected and influential figure in the nationalist movement. In the spring of 1923 Gerlich had a meeting with Adolf Hitler. It is believed that at the meeting, Hitler gave his word of honour that he would support the right-wing Bavarian prime minister Gustav von Kahr and would not resort to illegal putschist methods. Gerlich was appalled by the Beer Hall Putsch on 8th November 1923. Gerlich wrote in his newspaper that it was "one of the greatest betrayals in German history".

Gerlich left the Münchner Neueste Nachrichten after he was taken over by the reactionary nationalist, Alfred Hugenberg, who had started funding Hitler. In 1931, with the financial support of Prince Erich von Waldburg-Zeil, he began publishing a weekly political newspaper, Der Gerade Weg, that attacked the policies of the extreme right, National Socialist German Workers Party and the extreme left, German Communist Party (KPD). Gerlich advocated the restoration of the monarchy under Crown Prince Rupprecht.

In his newspaper, Gerlich predicted that if Hitler gained power it would lead to "enmity with neighbouring countries, internal totalitarianism, civil war, international war, lies, hatred, fratricide and infinite trouble." Ron Rosenbaum has pointed out that what makes Gerlich so unusual is that he was "an early, credulous supporter of the extreme nationalist politics Hitler represented" but he became the "most outspoken centre of anti-Hitler journalism on the conservative side of the political spectrum" in Germany.

On the morning of Saturday, 19th September, 1931, Geli Raubal, the niece of Adolf Hitler, was found on the floor of her room in the flat. She had been killed by a Walther 6.35 pistol that was owned by Hitler. Anti-Hitler newspapers, including Der Gerade Weg, suggested that Hitler had murdered Geli. According to the son of a man who worked for Gerlich, the newspaper got hold of a copy of "a state's attorney inquiry into the matter of Geli Raubal" that purportedly "showed that Geli was killed by order of Hitler."

Ronald Hayman, the author of Hitler & Geli (1997) has pointed out: "Seeing an opportunity to discredit Hitler, Gerlich used all his journalistic skills to investigate Geli's death. As his suspicions hardened, he collected evidence for publication in pamphlet form. If we can trust the summary of the pamphlet in The Memoirs of Bridget Hitler, he got affidavits from Willi Schmidt, the critic Geli had consulted about teachers in Vienna, and from one of the police inspectors who had visited the flat. This man - we do not know whether it was Sauer or Forster - believed that Hitler had been in the flat when the shot was fired.... Gerlich came to the conclusion that, instead of leaving for Nuremburg, Hitler had postponed his trip. Herr Zehnter, the owner of a Munich restaurant called the Bratwurstglockl, testified that Hitler arrived with Geli on the evening of Friday the 18th, that they were in a private room on the first floor till nearly one in the morning, and that Hitler, who rarely touched alcohol, was drinking beer. According to this summary of the pamphlet, he and Geli went back to the flat, where he threatened her with his revolver and shot her."

It has been claimed by Ron Rosenbaum that Adolf Hitler was particularly upset by an article by Gerlich that appeared on 17th July 1932 in Der Gerade Weg, that had the headline, "Does Hitler have Mongolian Blood?". In his book, Explaining Hitler: The Search for the Origins of his Evil (1998), Rosenbaum argues: "It still has the power to shock: Adolf Hitler married to a black bride. More than six decades after this extraordinary photocomposite image of Hitler in top hat and wedding tails, arm in arm with a black bride in a scene of wedding-day bliss, appeared on the front page of one of Munich's leading newspapers, this mocking representation of Hitler - in a context of decapitation, miscegeneration, transgressive sex, and violent defacement - still gives off an aura of recklessness of danger."

In the article Fritz Gerlich uses Hitler's ridiculous "racial science" to prove Hitler was not Aryan but Mongolian. He takes a close look at Hitler's nose, which he describes as "Slavonic". The Slavic type, he points out, "was formed by the intermingling after the Hun invasion of Mongols with original Slav bloodstock." Gerlich goes on to argue: "The war-strategy of those times made it customary for the victorious armies to have sex with the woman and girls of the defeated peoples... We have to suppose that in the home region of Hitler's family foreign, no Nordic blood remained."

Gerlich then goes on to look at Hitler's political ideas: "Adolf Hitler explains that in his political movement there is only one will and that's his... He never has to explain what he does... his followers have to carry out his commands without any information... The contrast between the real Nordic ideal and the one of Hitler cannot be expressed any more dramatically. Hitler's attitude is absolutely un-Nordic and un-Germanic. It is, racially, pure Mongolian... It is Mongolian absolute despotism that is expressed in Hitler's attitude and that can be explained by the fact that this man is a typical bastard who has mainly non-Nordic blood in his veins."

In a follow-up article the next week's edition of Der Gerade Weg, Gerlich argues: "We can't understand how people who call themselves righteous Catholics could feel upset by the juxtaposition of Hitler and a Negro woman. What exactly bothers you, dear ladies and gentlemen? Didn't you learn, in the first principles of our religion's catechism, not only that all men have their souls bestowed on them by God but also that we are all descendants of one father and one mother, children of Adam and Eve: According to our own Catholic principles, Negroes are our brothers and sisters even by blood, It is totally impossible for those of us with Catholic world views to 'degrade' a Central European like Adolf Hitler by pairing him with a Negro woman. A Negro woman isn't a person of inferior race.... We regard a Negro woman as our sister in blood."

On 9th March, 1933, Max Amann and Emil Maurice led a gang of stormtroopers into the Gerlich's offices, smashed all the machines and destroyed the contents of desks, files, cupboards and drawers, including the copy for the next issue of the newspaper. Ronald Hayman has suggested that the newspaper planned to carry articles on the death of Geli Raubal and on the Reichstag Fire.

According to Ron Rosenbaum, the author of Explaining Hitler: The Search for the Origins of his Evil (1998): "The nature of the expose he'd been about to publish - some said it concerned the circumstances of the death of Hitler's half-niece Geli Raubal in his apartment, others said it concerned the truth about the February 1933 Reichstag fire or foreign funding of the Nazis - has been effectively lost to history."

Fritz Gerlich was taken to Dachau where he was murdered on 30th June, 1934, the Night of the Long Knives. To notify his wife, they sent her his blood-spattered spectacles. Other Catholics murdered that day included Erich Klausener, the President of the Catholic Action movement and Adalbert Probst, national director of the Catholic Youth Sports Association. Richard Evans, the author of The Third Reich in Power (2005) has suggested that "Klausener's murder sent a clear message to Catholics that a revival of independent Catholic political activity would not be tolerated".

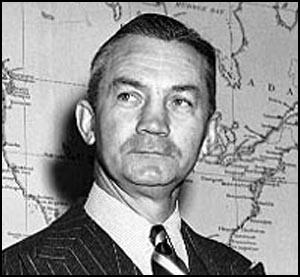

On this day in 1892 American politician James Forrestal, the son of an Irish immigrant, was born in Matteawan, New York. After attending local schools he joined the Matteawan Journal at the age of sixteen. He also worked as a reporter on the Mount Vernon Argus before becoming city editor on the Poughkeepsie News Press.

Aware that progress would be slow without a college education, in 1912 he went to Princeton University. Three years later Forrestal left Princeton without getting a degree and went to work for the New York World.

In 1916 Forrestal joined the banking firm Dillon, Read & Company as a bond salesman in New York. The following year he moved to Canada where he joined the Royal Flying Corps. By 1918 he qualified as a pilot but did not see active service in the First World War.

After the war Forrestal returned to Dillon, Read & Company. Progress was rapid. He was appointed head of the New York office's sales department and in 1923 was a partner in the firm. Three years later he became vice-president and in 1938, when he was forty-six years old, he became its president.

In 1940 Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Forrestal as one of his advisers. His duties included working as a liaison officer between the president, the Treasury Department and other governmental financial agencies. Roosevelt was impressed with Forrestal and in August 1940 he was appointed under secretary of the navy with special responsibility for procurement and production. In 1941 Forrestal went to London to negotiate the Lend-Lease agreement.

When William Knox died on 23rd April 1944, Forrestal became the new Secretary of the Navy. In this post he visited the Pacific three times and Europe twice and watched the D-Day landings in June, 1944. Forrestal held the post until September 1947 when he became Secretary of Defence.

After the war Forrestal became associated with the campaign against communism. This upset liberals in Washington who still believed it was possible to develop good relations with Joseph Stalin and the Soviet Union. In September 1946 he joined with James F. Byrnes to get Henry Wallace sacked after he made a speech calling for an end to the Cold War.

In 1948 the journalist Drew Pearson revealed in his newspaper column that during the 1930s Forrestal had been guilty of tax evasion and share manipulation. Other journalists made claims that Forrestal had owned shares in large companies in Nazi Germany and had used his influence to stop the bombing of German cities during the Second World War.

Harry S. Truman was unhappy with Forrestal's performance as Secretary of Defence and on 28th March 1949 forced him to resign from office. Soon afterwards, Forrestal, suffering from depression, was admitted to Bethesda Hospital. On 22nd May 1949 James Forrestal committed suicide by throwing himself out of a 16th-floor hospital window.

On this day in 1899 Gale Sondergaard was born in Litchfield, Minnesota. She became an actress and while working for the Theatre Guild met and married Herbert Biberman. The couple moved to Hollywood and she acted in 38 films in thirteen years. This included Anthony Adverse (1936), The Life of Emile Zola (1937), Sons of Liberty (1939), The Mark of Zorro (1940), A Night to Remember (1943), and Road to Rio (1947).

After the Second World War the House of Un-American Activities Committee began an investigation into the Hollywood Motion Picture Industry. In September 1947, the HUAC interviewed 41 people who were working in Hollywood. These people attended voluntarily and became known as "friendly witnesses". During their interviews they named several people who they accused of holding left-wing views. This included Gondergaard and her husband Herbert Biberman.

Biberman appeared before the HUAC on 29th October, 1947, but like, Alvah Bessie, Lester Cole, Albert Maltz, Adrian Scott, Dalton Trumbo, Edward Dmytryk, Ring Lardner Jr., Samuel Ornitz and John Howard Lawson, he refused to answer any questions. Known as the Hollywood Ten, they claimed that the 1st Amendment of the United States Constitution gave them the right to do this. The House of Un-American Activities Committee and the courts during appeals disagreed and all were found guilty of contempt of Congress and Herbert Biberman was sentenced to six months in Texarkana Prison and fined $1,000.

Blacklisted by the studios, Sondergaard did not appear in another Hollywood film until Slaves (1969). This was followed by Savage Intruder (1970), Pleasantville (1976), The Return of a Man Called Horse (1976) and Echoes (1983). Gale Sondergaard died on 14th August, 1985.

On this day in 1914 Hale Boggs was born in Long Beach, Mississippi. He graduated from the law department of Tulane University in 1935 and soon afterwards started work as a lawyer in New Orleans.

A member of the Democratic Party he was elected to Congress and served from January 1941 to January 1943. He left politics in 1943 to enlist in the United States Naval Reserve and served in the Potomac River Naval Command during the rest of the Second World War.

After the war Boggs returned to politics and in January 1946 was once again elected to the Senate. He held several posts including majority whip, chairman of the Special Committee on Campaign Expenditures and majority leader.

On the death of John F. Kennedy in 1963 his deputy, Lyndon B. Johnson, was appointed president. He immediately set up a commission to "ascertain, evaluate and report upon the facts relating to the assassination of the late President John F. Kennedy." Boggs was invited to join the commission under the chairmanship of Earl Warren. Other members of the commission included Richard B. Russell, Gerald Ford, Allen W. Dulles, John J. McCloy and John S. Cooper.

The Warren Commission reported to President Johnson ten months later. It reached the following conclusions:

(1) The shots which killed President Kennedy and wounded Governor Connally were fired from the sixth floor window at the southeast corner of the Texas School Book Depository.

(2) The weight of the evidence indicates that there were three shots fired.

(3) Although it is not necessary to any essential findings of the Commission to determine just which shot hit Governor Connally, there is very persuasive evidence from the experts to indicate that the same bullet which pierced the President's throat also caused Governor Connally's wounds. However, Governor Connally's testimony and certain other factors have given rise to some difference of opinion as to this probability but there is no question in the mind of any member of the Commission that all the shots which caused the President's and Governor Connally's wounds were fired from the sixth floor window of the Texas School Book Depository.

(4) The shots which killed President Kennedy and wounded Governor Connally were fired by Lee Harvey Oswald.

(5) Oswald killed Dallas Police Patrolman J. D. Tippit approximately 45 minutes after the assassination.

(6) Within 80 minutes of the assassination and 35 minutes of the Tippit killing Oswald resisted arrest at the theater by attempting to shoot another Dallas police officer.

(7) The Commission has found no evidence that either Lee Harvey Oswald or Jack Ruby was part of any conspiracy, domestic or foreign, to assassinate President Kennedy.

(8) In its entire investigation the Commission has found no evidence of conspiracy, subversion, or disloyalty to the US Government by any Federal, State, or local official.

(9) On the basis of the evidence before the Commission it concludes that, Oswald acted alone.

Boggs had doubts that John F. Kennedy and J. D. Tippit had been killed by Lee Harvey Oswald and that Jack Ruby was not part of any conspiracy." According to Bernard Fensterwald: "Almost from the beginning, Congressman Boggs had been suspicious over the FBI and CIA's reluctance to provide hard information when the Commission's probe turned to certain areas, such as allegations that Oswald may have been an undercover operative of some sort. When the Commission sought to disprove the growing suspicion that Oswald had once worked for the FBI, Boggs was outraged that the only proof of denial that the FBI offered was a brief statement of disclaimer by J. Edgar Hoover. It was Hale Boggs who drew an admission from Allen Dulles that the CIA's record of employing someone like Oswald might be so heavily coded that the verification of his service would be almost impossible for outside investigators to establish."

It has been claimed by John Judge that when Alan Dulles was asked by Hale Boggs about releasing the evidence, he replied, "Go ahead and print it, nobody will read it anyway."

According to one of his friends: "Hale felt very, very torn during his work (on the Commission) ... he wished he had never been on it and wished he'd never signed it (the Warren Report)." Another former aide argued that, "Hale always returned to one thing: Hoover lied his eyes out to the Commission - on Oswald, on Ruby, on their friends, the bullets, the gun, you name it."

Hale Boggs disappeared while on a campaign flight from Anchorage to Juneau, Alaska, on 16th October, 1972. Also killed in the accident was Nick Begich, a member of the House of Representatives. No bodies were ever found and in 1973 his wife, Lindy Boggs, was elected in her husband's place.

The Los Angeles Star, on November 22, 1973, reported that before his death Boggs claimed he had "startling revelations" on Watergate and the assassination of John F. Kennedy.

On this day in 1928 H. H. Asquith died. Asquith became prime minister on 5th April 1908. Asquith appointed David Lloyd George as his Chancellor of the Exchequer. Other members of his team included Winston Churchill (Board of Trade), Herbert Gladstone (Home Secretary), Charles Trevelyan (Board of Education), Richard Haldane (Secretary of State for War), Reginald McKenna (First Lord of the Admiralty) and John Burns (President of the Local Government Board).

Asquith took a gamble when he appointed Lloyd George to such a senior position. He was far to the left of Asquith but he reasoned that a disgruntled Lloyd George would be less of a problem inside the government as out. Asquith wrote: "The offer which I make is a well-deserved tribute to your long and eminent service to our party and to the splendid capacity which you have shown in your administration of the Board of Trade."

David Lloyd George in one speech had warned that if the Liberal Party did not pass radical legislation, at the next election, the working-class would vote for the Labour Party: "If at the end of our term of office it were found that the present Parliament had done nothing to cope seriously with the social condition of the people, to remove the national degradation of slums and widespread poverty and destitution in a land glittering with wealth, if they do not provide an honourable sustenance for deserving old age, if they tamely allow the House of Lords to extract all virtue out of their bills, so that when the Liberal statute book is produced it is simply a bundle of sapless legislative faggots fit only for the fire - then a new cry will arise for a land with a new party, and many of us will join in that cry."

Lloyd George had been a long opponent of the Poor Law in Britain. He was determined to take action that in his words would "lift the shadow of the workhouse from the homes of the poor". He believed the best way of doing this was to guarantee an income to people who were to old to work. Based on the ideas of Tom Paine that first appeared in his book Rights of Man, Lloyd George's proposed the Old Age Pensions Act in his first budget.

In a speech on 15th June 1908, he pointed out: "You have never had a scheme of this kind tried in a great country like ours, with its thronging millions, with its rooted complexities... This is, therefore, a great experiment... We do not say that it deals with all the problem of unmerited destitution in this country. We do not even contend that it deals with the worst part of that problem. It might be held that many an old man dependent on the charity of the parish was better off than many a young man, broken down in health, or who cannot find a market for his labour."

However, the Labour Party was disappointed by the proposal. Along with the Trade Union Congress they had demanded a pension of at least five shillings a week for everybody of sixty or over, Lloyd George's scheme gave five shillings a week to individuals over seventy; and for couples the pension was to be 7s. 6d. Moreover, even among the seventy-year-olds not everyone was to qualify; as well as criminals and lunatics, people with incomes of more than £26 a year (or £39 a year in the case of couples) and people who would have received poor relief during the year prior to the scheme's coming into effect, were also disqualified."

To pay for these pensions Lloyd George had to raise government revenues by an additional £16 million a year. In 1909 Lloyd George announced what became known as the People's Budget. This included increases in taxation. Whereas people on lower incomes were to pay 9d. in the pound, those on annual incomes of over £3,000 had to pay 1s. 2d. in the pound. Lloyd George also introduced a new super-tax of 6d. in the pound for those earning £5,000 a year. Other measures included an increase in death duties on the estates of the rich and heavy taxes on profits gained from the ownership and sale of property. Other innovations in Lloyd George's budget included labour exchanges and a children's allowance on income tax.

Archibald Primrose, Lord Rosebery, the former Liberal Party leader, stated that: "The Budget, was not a Budget, but a revolution: a social and political revolution of the first magnitude... To say this is not to judge it, still less to condemn it, for there have been several beneficent revolutions." However, he opposed the Budget because it was "pure socialism... and the end of all, the negation of faith, of family, of property, of Monarchy, of Empire."

David Lloyd George admitted that he would never have got his proposals through the Cabinet without the strong support of Asquith. He told his brother: "Budgeting all day... the Cabinet was very divided... Prime Minister decided in my favour to my delight". He told a friend: "The Prime Minister has backed me up through thick and thin with splendid loyalty. I have the deepest respect for him and he has real sympathy for the ordinary and the poor."

His other main supporter in the Cabinet was Winston Churchill. He spoke at a large number of public meetings of the pressure group he formed, the Budget League. Churchill rarely missed a debate on the issue and one newspaper report suggested that he had attended one late night debate in the House of Commons in his pajamas. Some historians have claimed that both men were using the measure to further their political careers.

Robert Lloyd George, the author of David & Winston: How a Friendship Changed History (2005) has suggested that their main motive was to prevent socialism in Britain: "Churchill and Lloyd George intuitively saw the real danger of socialism in the global situation of that time, when economic classes were so divided. In other European countries, revolution would indeed sweep away monarchs and landlords within the next ten years. But thanks to the reforming programme of the pre-war Liberal government, Britain evolved peacefully towards a more egalitarian society. It is arguable that the peaceful revolution of the People's Budget prevented a much more bloody revolution."

The Conservatives, who had a large majority in the House of Lords, objected to this attempt to redistribute wealth, and made it clear that they intended to block these proposals. Lloyd George reacted by touring the country making speeches in working-class areas on behalf of the budget and portraying the nobility as men who were using their privileged position to stop the poor from receiving their old age pensions. The historian, George Dangerfield, has argued that Lloyd George had created a budget that would destroy the House of Lords: "It was like a kid, which sportsmen tie up to a tree in order to persuade a tiger to its death."

Asquith's strategy was to offer the peers the minimum of provocation and hope to finesse them into passing the legislation. Lloyd George had a different style and in a speech on 30th July, 1909, in the working-class district of Limehouse in London on the selfishness of rich men unwilling "to provide for the sick and the widows and orphans". He concluded his speech with the threat that if the peers resisted, they would be brushed aside "like chaff before us".

Edward VII was furious and suggested to Asquith that Lloyd George was a "revolutionary" and a "socialist". Asquith explained that the support of the King was vital if the House of Lords was to be outmanoeuvred. Asquith explained to Lloyd George that the King "sees in the general tone, and especially in the concluding parts, of your speech, a menace to property and a Socialistic spirit". He added it was important "to avoid alienating the King's goodwill... and... what is needed is reasoned appeal to moderate and reasonable men" and not to "rouse the suspicions and fears of the middle class".

It was clear that the House of Lords would block the budget. H. H. Asquith asked the King to create a large number of Peers that would give the Liberals a majority. Edward VII refused and his private secretary, Francis Knollys, wrote to Asquith that "to create 570 new Peers, which I am told would be the number required... would practically be almost an impossibility, and if asked for would place the King in an awkward position".

On 30th November, 1909, the Peers rejected the Finance Bill by 350 votes to 75. Asquith had no option but to call a general election. In January 1910, the Liberals lost votes and was forced to rely on the support of the 42 Labour Party MPs to govern. Asquith increased his own majority in East Fife but he was prevented from delivering his acceptance speech by members of the Women Social & Political Union who were demanding "Votes for Women".

John Grigg, the author of The People's Champion (1978) argues that the reason why the "people failed to give a sweeping, massive endorsement to the People's Budget" was that the electorate in 1910 was "by no means representative of the whole British nation". He points out that "only 58 per cent of adult males had the vote, and it is a fair assumption that the remaining 42 per cent would, if enfranchised, have voted in very large numbers for Liberal or Labour candidates. In what was still a disproportionately middle-class electorate the fear of Socialism was strong, and many voters were susceptible to the argument that the Budget was a first installment of Socialism."

Some of his critics on the left of the party believed that Asquith had not mounted a more aggressive campaign against the House of Lords. It was argued that instead of threatening its power to veto legislation, he should have advocated making it a directly elected second chamber. Asquith felt this was a step to far and was more interested in a negotiated settlement. However, to Colin Clifford, this made Asquith look "weak and indecisive".

In a speech on 21st February, 1910, Asquith outlined his plans for reform: "Recent experience has disclosed serious difficulties due to recurring differences of strong opinion between the two branches of the Legislature. Proposals will be laid before you, with convenient speed, to define the relations between the Houses of Parliament, so as to secure the undivided authority of the House of Commons over finance and its predominance in legislation."

The Parliament Bill was introduced later that month. "Any measure passed three times by the House of Commons would be treated as if it had been passed by both Houses, and would receive the Royal Assent... The House of Lords was to be shorn absolutely of power to delay the passage of any measure certified by the Speaker of the House of Commons as a money bill, but was to retain the power to delay any other measure for a period of not less than two years."

Edward VII died in his sleep on 6th May 1910. His son, George V, now had the responsibility of dealing with this difficult constitutional question. David Lloyd George had a meeting with the new king and had an "exceedingly frank and satisfactory talk about the political crisis". He told his wife that he was not very intelligent as "there's not much in his head". However, he "expressed the desire to try his hand at conciliation... whether he will succeed is somewhat doubtful."

James Garvin, the editor of The Observer, argued it was time that the government reached a negotiated settlement with the House of Lords: "If King Edward upon his deathbed could have sent a last message to his people, he would have asked us to lay party passion aside, to sign a truce of God over his grave, to seek... some fair means of making a common effort for our common country... Let conference take place before conflict is irrevocably joined."

A Constitutional Conference was established with eight members, four cabinet ministers and four representatives from the Conservative Party. Over the next six months the men met on twenty-one occasions. However, they never came close to an agreement and the last meeting took place in November. George Barnes, the Labour Party MP, called for an immediate creation of left-wing peers. However, when a by-election at Walthamstow suggested a slight swing to the Liberals, Asquith decided to call another General Election.

David Lloyd George called on the British people to vote for a change in the parliamentary system: "How could anyone defend the Constitution in its present form? No country in the world would look at our system - no free country, I mean... France has a Senate, the United States has a Senate, the Colonies have Senates, but they are all chosen either directly or indirectly by the people."

The general election of December, 1910, produced a House of Commons which was almost identical to the one that had been elected in January. The Liberals won 272 seats and the Conservatives 271, but the Labour Party (42) and the Irish (a combined total of 84) ensured the government's survival as long as it proceeded with constitutional reform and Home Rule.

The Parliament Bill, which removed the peers' right to amend or defeat finance bills and reduced their powers from the defeat to the delay of other legislation, was introduced into the House of Commons on 21st February 1911. It completed its passage through the Commons on 15th May. A committee of the House of Lords then amended the bill out of all recognition.

According to Lucy Masterman, the wife of Charles Masterman, the Liberal MP for West Ham North, that David Lloyd George had a secret meeting with Arthur Balfour, the leader of the Conservative Party. Lloyd George had bluffed Balfour into believing that George V had agreed to create enough Liberal supporting peers to pass a new Parliament Bill.

Although a list of 249 candidates for ennoblement, including Thomas Hardy, Bertrand Russell, Gilbert Murray and J. M. Barrie, had been drawn up, they had not yet been presented to the King. After the meeting Balfour told Conservative peers that to prevent the Liberals having a permanent majority in the House of Lords, they must pass the bill. On 10th August 1911, the Parliament Act was passed by 131 votes to 114 in the Lords.

On this day in 1935 David Low published a cartoon on the Italian invasion of Ethiopia. In October 1935 Pierre Laval joined with Samuel Hoare, Britain's foreign secretary, in an effort to resolve the crisis created by the Italian invasion of Ethiopia. The secret agreement, known as the Hoare-Laval Pact, proposed that Italy would receive two-thirds of the territory it conquered as well as permission to enlarge existing colonies in East Africa. In return, Ethiopia was to receive a narrow strip of territory and access to the sea. Details of the Hoare-Laval Pact was leaked to the press on 10th December, 1935. The scheme was widely denounced as appeasement of Italian aggression and Laval and Hoare were both forced to resign.

On this day in 1998 American journalist Martha Gellhorn died in London. Gellhorn, the daughter of George Gellhorn, a gynecologist, and Edna Fischel, was born in St. Louis on 8th November, 1908. When she was a child her mother was involved in the women's suffrage movement.

Gellhorn attended Bryn Mawr College but left in 1927 to begin a career as a writer. Her first articles appeared in the New Republic, but determined to become a foreign correspondent, she moved to France to work for the United Press bureau in Paris.

While in Europe she became active in the pacifist movement and wrote about her experiences in the book, What Mad Pursuit (1934). When Gellhorn returned home she was hired by Harry Hopkins as an investigator for the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, where she had the task of reporting the impact of the Depression on the United States. Her reports for that agency caught the attention of Eleanor Roosevelt, and the two women became lifelong friends. Her findings were the basis of a novella, The Trouble I've Seen (1936).

In 1937 Gellhorn was employed by Collier's Weekly to report the Spanish Civil War. While there she started an affair with Ernest Hemingway and the couple married in 1940. Gellhorn travelled to Germany where she reported the rise of Adolf Hitler and in 1938 was in Czechoslovakia. After the outbreak of the Second World War wrote about these events in the novel, A Stricken Field (1940).

Gellhorn worked for Collier's Weekly throughout the Second World War and later recalled how she "followed the war wherever I could reach it." This included reporting from Finland, Hong Kong, Burma, Singapore and Britain. She even impersonated a stretcher bearer in order to witness the D-Day landings. Her book about the war, The Undefeated, was published in 1945.

Gellhorn also covered the arrival of allied troops at Dachau: "In their joy to be free, and longing to see their friends who had come at last, many prisoners rushed to the fence and died electrocuted. There were those who died cheering, because that effort of happiness was more than their bodies could endure. There were those who died because now they had food, and they ate before they could be stopped, and it killed them. I do not know words to describe the men who have survived this horror for years, three years, five years, ten years, and whose minds are as clear and unafraid as the day they entered. I was in Dachau when the German armies surrendered unconditionally to the Allies. We sat in that room, in that accursed cemetery prison, and no one had anything more to say. Still, Dachau seemed to me the most suitable place in Europe to hear the news of victory. For surely this war was made to abolish Dachau, and all the other places like Dachau, and everything that Dachau stood for, and to abolish it for ever."

After the war Gellhorn worked for Atlantic Monthly. This included all the major world conflicts, including the Vietnam War. In an interview with Shelia MacVicar she pointed out: "I hated Vietnam the most, because I felt personally responsible. It was my own country doing this abomination. I am talking about what was done in South Vietnam to the people whom we, supposedly, had come to save. I'm seeing napalmed children in the hospital, seeing old women with a piece of white sulphur burning away inside of them, seeing the destroyed villages, seeing people dropping of hunger and dying in the streets. My complete horror remains with me as a source of grief and anger and shame that surpasses all the others."

Martha Gellhorn published a large number of books including a collection of articles on war, The Face of War (1959), a novel about McCarthyism in the United States, The Lowest Trees Have Tops (1967), an account of her life with Ernest Hemingway, entitled, Travels With Myself and Another (1978) and a collection of her peacetime journalism, The View From the Ground (1988).