On this day on 9th June

On this day in 1781 George Stephenson, the son of a colliery fireman, was born at Wylam, eight miles from Newcastle-upon-Tyne, on 9th June, 1781. The cottage where the Stephenson family lived was next to the Wylam Wagonway, and George grew up with a keen interest in machines.

George's first employment was herding cows but when he was fourteen he joined his father at the Dewley Colliery. George was an ambitious boy and at the age of eighteen he began attending evening classes where he learnt to read and write.

According to Maurice W. Kirby: "Stephenson also received instruction in arithmetic, a subject which he mastered quickly, although theoretical calculation remained beyond his capacity. Writing, too, proved to be a persistent difficulty, and in later life he was obliged to employ a secretary to write for him".

Stephenson married Frances Henderson, the daughter of a poor farmer, on 28th November 1802. His only son, Robert Stephenson, was born the following year. Like many colliery workers, he took on a variety of freelance jobs, notably clock-mending. Samuel Smiles has pointed out: "He also diligently set himself to study the principles of mechanics, and to master the laws by which the engine worked. For a workman, he was even at that time more than ordinarily speculative, often taking up strange theories, and trying to sift out the truth that was in them."

Francis Stephenson, who was twelve years older than her husband, died of consumption in May 1806 soon after giving birth to a daughter who also died. He left his young son Robert in the care of relatives and went to Scotland in search of better-paid work but he was forced to return when his father was blinded in a mining accident.

In 1808 he found employment as an engineman at Killingworth Colliery. Every Saturday he took the engines to pieces in order to understand how they were constructed. This included machines made by Thomas Newcomen and James Watt. By 1812 Stephenson's knowledge of engines resulted in him being employed as the colliery's engine wright. The following year the mine-owners asked Stephenson to build a steam engine.

In 1813 George Stephenson became aware of attempts by William Hedley and Timothy Hackworth, at Wylam Colliery, to develop a locomotive. Stephenson successfully convinced his colliery manager, Nicholas Wood, his to allow him to try to produce a steam-powered machine. By 1814 he had constructed a locomotive that could pull thirty tons up a hill at 4 mph. Stephenson called his locomotive, the Blucher, and like other machines made at this time, it had two vertical cylinders let into the boiler, from the pistons of which rods drove the gears.

Where Stephenson's locomotive differed from those produced by John Blenkinsop, Hedley and Hackworth, was that the gears did not drive the rack pinions but the flanged wheels. The Blucher was the first successful flanged-wheel adhesion locomotive. Stephenson continued to try and improve his locomotive and in 1815 he changed the design so that the connecting rods drove the wheels directly. These wheels were coupled together by a chain. Over the next five years Stephenson built sixteen engines at Killingworth. Most of these were used locally but some were produced for the Duke of Portland's wagonway from Kilmarnock to Troon.

Roger Osborne, the author of Iron, Steam and Money: The Making of the Industrial Revolution (2013) has argued: "Stephenson was a brilliant builder of locomotives, his greatest contribution was to bring engines and railways together. He improved the tracks, which were still liable to buckle or break even if they were made of cast iron, and worked to distribute the weight of the engines through more axles."

Working at a colliery, George Stephenson was fully aware of the large number of accidents caused by explosive gases. In his spare time Stephenson began work on a safety lamp for miners. By 1815 he had developed a lamp that did not cause explosions even in parts of the pit that were full of inflammable gases. Unknown to Stephenson, Humphry Davy was busy producing his own safety lamp.

The owners of the colliery were impressed with Stephenson's achievements and in 1819 he was given the task of building a eight mile railroad from Hetton to the River Wear at Sunderland. While he was working on this Stephenson became convinced that to be successful, steam railways had to be made as level as possible by civil engineering works. The track was laid out in sections. The first part was worked by locomotives, this was followed by fixed engines and cables. After the railway reached 250 feet above sea level, the coal wagons travelled down over 2 miles of self-acting inclined plane. This was followed by another 2 miles of locomotive haulage. George Stephenson only used fixed engines and locomotives and had therefore produced the first ever railway that was completely independent of animal power.

On 19th April 1821 an Act of Parliament was passed that authorized a company owned by Edward Pearse to build a horse railway that would link the collieries in West Durham, Darlington and the River Tees at Stockton. Stephenson arranged a meeting with Pease and suggested that he should consider building a locomotive railway. Stephenson told Pease that "a horse on an iron road would draw ten tons for one ton on a common road". Stephenson added that the Blutcher locomotive that he had built at Killingworth was "worth fifty horses".

That summer Edward Pease took up Stephenson's invitation to visit Killingworth Colliery. When Pease saw the Blutcher at work he realised George Stephenson was right and offered him the post as the chief engineer of the Stockton & Darlington company. It was now now necessary for Pease to apply for a further Act of Parliament. This time a clause was added that stated that Parliament gave permission for the company "to make and erect locomotive or moveable engines". Stephenson wrote to Pease: "I am glad to learn that the Parliament Bill has been passed for the Darlington Railway. I am much obliged by the favourable sentiments you express towards me, and shall be happy if I can be of service in carrying into execution your plans".

George Stephenson began working with William Losh, who owned an ironworks in Newcastle. Together they patented their own make of cast iron rails. In 1821 John Birkinshaw, an engineer at Bedlington Ironworks, developed a new method of rolling wrought iron rails in fifteen feet lengths. Stephenson went to see these malleable rails and decided they were better than those that he was making with Losh. Although it cost him a considerable amount of money, Stephenson decided to use Birkinshaw's rails, rather than those he made with Losh, on the Stockton & Darlington line.

In 1823 Edward Pease joined with Michael Longdridge, George Stephenson and his son Robert Stephenson, to form a company to make the locomotives. The Robert Stephenson & Company, at Forth Street, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, became the world's first locomotive builder. Stephenson recruited Timothy Hackworth, one of the engineers who had helped William Hedley to produce Puffing Billy, to work for the company. The first railway locomotive, Locomotion, was finished in September 1825. The locomotive was similar to those that Stephenson had produced at the collieries at Killingworth and Heaton.

Work on the track began in 1822. George Stephenson used malleable iron rails carried on cast iron chairs. These rails were laid on wooden blocks for 12 miles between Stockton and Darlington. The 15 mile track from the collieries and Darlington were laid on stone blocks. While building this railway Stephenson discovered that on a smooth, level track, a tractive force of ten pounds would move a ton of weight. However, when there was a gradient of 1 in 200, the hauling power of a locomotive was reduced by 50 per cent. Stephenson came to the conclusion that railways must be specially designed with the object of avoiding as much as possible changes in gradient. This meant that considerable time had to be spent on cuttings, tunnels and embankments.

The Stockton & Darlington line was opened on 27th September, 1825. Large crowds saw George Stephenson at the controls of the Locomotion as it pulled 36 wagons filled with sacks of coal and flour. The initial journey of just under 9 miles took two hours. However, during the final descent into the Stockton terminus, speeds of 15 mph (24 kph) were reached.

The Durham County Advertiser reported: "The hour of ten arrived before all was ready to start. About this time the locomotive engine, or steam horse, as it was more generally termed, gave note of preparation. The scene, on the moving of the engine, sets description at defiance. Astonishment was not confined to the human species, for the beasts of the field and the fowls of the air seemed to view with wonder and awe the machine, which now moved onward at a rate of 10 or 12 mph with a weight of not less than 80 tons attached to it... The whole population of the towns and villages within a few miles of the railway seem to have turned out, and we believe we speak within the limits of truth, when we say that not less than 40 or 50,000 persons were assembled to witness the proceedings of the day."

The Stockton & Darlington line successfully reduced the cost of transporting coal. By 1825, locomotives on the railway were hauling trains of up to eighty tons at speeds of fifteen miles an hour. The reduction in his transport costs enabled Pearse to cut the price of his coal from 18s. to 8s. 6d. a ton. One newspaper reported that the "Stockton & Darlington rail-road, a work which will for ever reflect honour on its authors, for the new and striking manner in which it practically demonstrated all the advantages of the invention."

In 1826 Stephenson was appointed engineer and provider of locomotives for the Bolton & Leigh railway. He also was the chief engineer of the proposed Liverpool & Manchester railway. Stephenson was faced with a large number of serious engineering problems. This included crossing the unstable peat bog of Chat Moss, a nine-arched viaduct across the Sankey Valley and a two-mile long rock cutting at Olive Mount.

The directors of the Liverpool & Manchester company were unsure whether to use locomotives or stationary engines on their line. To help them reach a decision, it was decided to hold a competition where the winning locomotive would be awarded £500. The idea being that if the locomotive was good enough, it would be the one used on the new railway.

The competition was held at Rainhill during October 1829. Each competing locomotive had to haul a load of three times its own weight at a speed of at least 10 mph. The locomotives had to run twenty times up and down the track at Rainhill which made the distance roughly equivalent to a return trip between Liverpool and Manchester. Afraid that heavy locomotives would break the rails, only machines that weighed less than six tons could compete in the competition. Ten locomotives were originally entered for the Rainhill Trials but only five turned up and two of these were withdrawn because of mechanical problems. Sans Pariel and Novelty did well but it was the Rocket, produced by George and his son, Robert Stephenson, that won the competition.

The Liverpool & Manchester railway was opened on 15th September, 1830. Fanny Kemble was an invited guest to the proceedings: "The most intense curiosity and excitement prevailed, and though the weather was uncertain, enormous masses of densely packed people lined the road, shouting and waving hats and handkerchiefs as we flew by them. We travelled at 35 miles an hour (swifter than a bird flies). When I closed my eyes this sensation of flying was quite delightful. I had been unluckily separated from my mother in the first distribution of places, but by an exchange of seats which she was enabled to make she rejoined me when I was at the height of my ecstasy, which was considerably damped by finding that she was frightened to death, and intent upon nothing but devising means of escaping from a situation which appeared to her to threaten with instant annihilation herself and all her travelling companions."

The prime minister, the Duke of Wellington, and a large number of important people attended the opening ceremony that included a procession of eight locomotives. Unfortunately, when the train stopped at a halfway point to take on water, one of the government ministers, William Huskisson, got down from his carriage and stepped on to the parrallel track where he was hit by a locomotive travelling in the opposite direction. He died later that day.

Thomas Southcliffe Ashton has argued that "it was only with the newly constructed Liverpool and Manchester Railway, that the potentialities of steam transport were fully realized". It soon became clear that large profits could be made by building railways and railways quickly became the basic infrastructure for the nation's transport. As they were built and run by individual companies at their own risk, the result was a fairly haphazard network, including many duplications of routes.

George Stephenson continued to work on improving the quality of the locomotives used on the railway lines he constructed. This included the addition of a steam-jet developed by Goldsworthy Gurney that increased the speed of the Rocket to 29 mph.

In 1838 Stephenson purchased Tapton House, a Georgian mansion near Chesterfield. Stephenson went into partnership with George Hudson and James Sanders and together they opened coalmines, ironworks and limestone quarries in the area. Stephenson also owned a small farm where he experimented with stock breeding, new types of manure and animal food. He also developed a method of fattening chickens in half the usual time. He did this by shutting them in dark boxes after a heavy feed.

Stephenson's second wife, Elizabeth Hindley, died in 1845. George Stephenson married for a third time just before he died at Tapton House, Chesterfield on 12th August, 1848.

On this day in 1817 Jeremiah Brandreth led 300 men on a march on Nottingham. Armed with a few pistols and pikes, Brandreth expected others to join him on the way to the city. This did not happen and the authorities had little difficulty dispersing the proposed insurrection.

Thirty-five of the men were charged with high treason. Brandreth and two others were sentenced to death and another eleven men were transported for life. The men were originally sentenced to being hanged, drawn and quartered, but the quartering was remitted.

On the scaffold one of the men shouted out that they were victims of Lord Sidmouth and Oliver the Spy. Percy Bysshe Shelley campaigned against the use of agent provocateurs in The Examiner. Edward Baines of the Leeds Mercury investigated their claims and was able to find enough evidence to implicate the government in the conspiracy. In his article exposing William Oliver, Baines described him as a "prototype of Lucifer, whose distinguishing characteristic is, first to tempt and then to destroy."

Jeremiah Brandreth (1817)

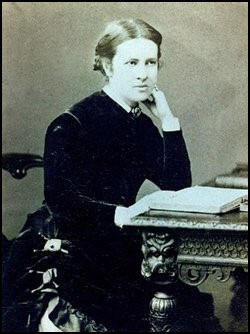

On this day in 1836 pioneer doctor Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, the daughter of Newson Garrett (1812–1893) and Louise Dunnell (1813–1903), was born in Whitechapel, London. Elizabeth's father, was the grandson of Richard Garrett, who founded the successful agricultural machinery works at Leiston.

Elizabeth's father had originally ran a pawnbroker's shop in London, but by the time she was born he owned a corn and coal warehouse in Aldeburgh, Suffolk. The business was a great success and by the 1850s Garrett could afford to send his children away to be educated.

After two years at a school in Blackheath, Elizabeth was expected to stay in the family home until she found a man to marry. However, Elizabeth was more interested in obtaining employment. While visiting a friend in London in 1854, Elizabeth met Emily Davies, a young women with strong opinions about women's rights. Davies introduced Elizabeth to other young feminists living in London.

In 1859 Garrett met Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman in the United States to qualify as a doctor. Elizabeth decided she also wanted a career in medicine. Her parents were initially hostile to the idea but eventually her father, Newson Garrett, agreed to support her attempts to become Britain's first woman doctor.

Garrett tried to study in several medical schools but they all refused to accept a woman student. Garrett therefore became a nurse at Middlesex Hospital and attended lectures that were provided for the male doctors. After complaints from male students Elizabeth was forbidden entry to the lecture hall.

Garrett discovered that the Society of Apothecaries did not specify that females were banned for taking their examinations. In 1865 Garrett sat and passed the Apothecaries examination. As soon as Garrett was granted the certificate that enabled her to become a doctor, the Society of Apothecaries changed their regulations to stop other women from entering the profession in this way. With the financial support of her father, Elizabeth Garrett was able to establish a medical practice in London.

Elizabeth Garrett was now a committed feminist and in 1865 she joined with her friends Emily Davies, Barbara Bodichon, Bessie Rayner Parkes, Dorothea Beale and Francis Mary Buss to form a woman's discussion group called the Kensington Society. The following year the group organized a petition asking Parliament to grant women the vote.

Although Parliament rejected the petition, the women did receive support from Liberals such as John Stuart Mill and Henry Fawcett. Elizabeth became friendly with Fawcett, the blind MP for Brighton, but she rejected his marriage proposal, as she believed it would damage her career. Fawcett later married her younger sister Millicent Garrett.

In 1866 Garrett established a dispensary for women in London (later renamed the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital) and four years later was appointed a visiting physician to the East London Hospital. Elizabeth was determined to obtain a medical degree and after learning French, went to the University of Paris where she sat and passed the required examinations. However, the British Medical Register refused to recognize her MD degree.

During this period Garrett became involved in a dispute with Josephine Butler over the Contagious Diseases Acts. Josephine believed these acts discriminated against women and felt that all feminists should support their abolition. Garrett took the view that the measures provided the only means of protecting innocent women and children.

Although she was a supporter of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) she was not an active member during this period. According to her daughter, Louisa Garrett Anderson, she thought "it would be unwise to be identified with a second unpopular cause. Nevertheless she gave her whole-hearted adherence."

The 1870 Education Act allowed women to vote and serve on School Boards. Garrett stood in London and won more votes than any other candidate. The following year she married James Skelton Anderson, a co-owner of the of the Orient Steamship Company, and the financial adviser to the East London Hospital.

Like other feminists at the time, Elizabeth Garrett retained her own surname. Although James Anderson supported Elizabeth's desire to continue as a doctor the couple became involved in a dispute when he tried to insist that he should take control of her earnings.

Elizabeth had three children, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Margaret who died of meningitis, and Alan. This did not stop her continuing her medical career and in 1872 she opened the New Hospital for Women in London, a hospital that was staffed entirely by women. Elizabeth Blackwell, the woman who inspired her to become a doctor, was appointed professor of gynecology.

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson also joined with Sophia Jex-Blake to establish a London Medical School for Women. Jex-Blake expected to put in charge but Garrett believed that her temperament made her unsuitable for the task and arranged for Isabel Thorne to be appointed instead. In 1883 Garrett Anderson was elected Dean of the London School of Medicine. Sophia Jex-Blake was the only member of the council who voted against this decision.

After the death of Lydia Becker in 1890, Elizabeth's sister, Millicent Garrett Fawcett was elected president of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. By this time Elizabeth was a member of the Central Committee of the NUWSS.

In 1902 Garrett Anderson retired to Aldeburgh. Garrett Anderson continued her interest in politics and in 1908 she was elected mayor of the town - the first woman mayor in England. When Garret Anderson was seventy-two, she became a member of the militant Women's Social and Political Union. In 1908 was lucky not to be arrested after she joined with other members of the WSPU to storm the House of Commons. In October 1909 she went on a lecture tour with Annie Kenney.

However, Elizabeth left the WSPU's in 1911 as she objected to their arson campaign. Her daughter Louisa Garrett Anderson remained in the WSPU and in 1912 was sent to prison for her militant activities. Millicent Garrett Fawcett was upset when she heard the news and wrote to her sister: "I am in hopes she will take her punishment wisely, that the enforced solitude will help her to see more in focus than she always does." However, the authorities realised the dangers of her going on hunger strike and released her.

Evelyn Sharp spent time with Elizabeth and Louisa Garrett Anderson at their cottage in the Highlands: "Dr. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, who had a summer cottage in that beautiful part of the Highlands. I went there on both occasions with her daughter Dr. Louisa Garrett Anderson, and we had great times together climbing the easier mountains and revelling in wonderful effects of colour that I have seen nowhere else except possibly in parts of Ireland.... It was, however, so entertaining to meet both these famous public characters in the more intimate and human surroundings of a summer holiday that we did not grudge the time given to working up a suffrage meeting in the village instead of tramping about the hills. Old Mrs. Garrett Anderson-old only in years, for there was never a younger woman in heart and mind and outlook than she was when I knew her before the war was a fascinating combination of the autocrat and the gracious woman of the world."

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson died in 17th December 1917.

On this day in 1838 The Northern Star praises the work of Chartist activist Elizabeth Hanson. Her husband, Abram Hanson, acknowledged the importance of "the women who are the best politicians, the best revolutionists, and the best political economists... should the men fail in their allegiance the women of Elland, who had sworn not to breed slaves, had registered a vow to do the work of men and women."

Elizabeth Hanson formed the Elland Female Radical Association in March, 1838. She argued "it is our duty, both as wives and mothers, to form a Female Association, in order to give and receive instruction in political knowledge, and to co-operate with our husbands and sons in their great work of regeneration." She became one of the movement's most effective speakers and one newspaper reported she "melted the hearts and drew forth floods of tears".

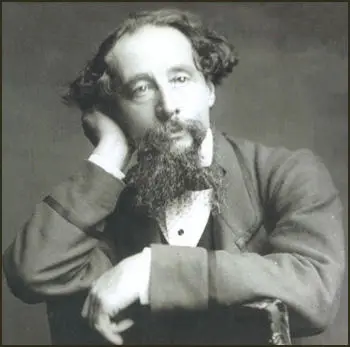

On this day in 1870 Charles Dickens died. The traditional version of his death was given by his official biographer, John Forster. He claimed that Dickens was having dinner with Georgina Hogarth at Gad's Hill Place when he fell to the floor: "Her effort then was to get him on the sofa, but after a slight struggle he sank heavily on his left side... It was now a little over ten minutes past six o'clock. His two daughters came that night with Mr. Frank Beard, who had also been telegraphed for, and whom they met at the station. His eldest son arrived early next morning, and was joined in the evening (too late) by his youngest son from Cambridge. All possible medical aid had been summoned. The surgeon of the neighbourhood (Stephen Steele) was there from the first, and a physician from London (Russell Reynolds) was in attendance as well as Mr. Beard. But human help was unavailing. There was effusion on the brain."

The Times reported on 11th June, 1870: "During the whole of Wednesday Mr Dickens had manifested signs of illness, saying that he felt dull, and that the work on which he was engaged was burdensome to him. He came to the dinner-table at six o'clock and his sister-in-law, Miss Hogarth, observed that his eyes were full of tears. She did not like to mention this to him, but watched him anxiously, until, alarmed by the expression of his face, she proposed sending for medical assistance.... Miss Hogarth went to him, and took his arm, intending to lead him from the room. After one or two steps he suddenly fell heavily on his left side, and remained unconscious and speechless until his death, which came at ten minutes past six on Thursday, just twenty-four hours after the attack."

George Dolby went to Gad's Hill Place as soon as he heard the news: "I went to Gad's Hill at once, where I was most kindly and gently received by Miss Dickens and Miss Hogarth, who told me the story of his last moments. The body lay in the dining-room, where Mr. Dickens had been seized with the fatal apoplectic fit. They asked me if I would go and see it, but I could not bear to do so. I wanted to think of him as I had seen him last. I went away from the house, and out on to the Rochester road. It was a bright morning in June, one of the days he had loved; on such a day we had trodden that road together many and many a time. But never again, we two, along that white and dusty way, with the flowering hedges over against us, and the sweet bare sky and the sun above us. We had taken our last walk together."

After the publication of her book, The Invisible Woman (1990), Claire Tomalin received a letter from J. C. Leeson, telling her a story that had been passed down in the family, originating with his highly respectable great-grandfather, a Nonconformist minister, J. Chetwode Postans, who became pastor of Lindon Grove Congregational Church in 1872. He was told later by the caretaker that Charles Dickens did not collapse atGad's Hill Place, but at another house "in compromising circumstances". Tomalin took a keen interest in this story as at the time, Ellen Ternan was living at nearby Windsor Lodge. After investigating all the evidence Tomalin has speculated that Dickens was taken ill while visiting the home he rented for Ternan. She then arranged for a horse-drawn vehicle to take Dickens to Gad's Hill.

John Everett Millais was invited to draw Dickens's dead face. On 16th June, Kate Dickens Perugini wrote to Millais: "Charlie - has just brought down your drawing. It is quite impossible to describe the effect it has had upon us. No one but yourself, I think, could have so perfectly understood the beauty and pathos of his dear face as it lay on that little bed in the dining-room, and no one but a man with genius bright as his own could have so reproduced that face as to make us feel now, when we look at it, that he is still with us in the house. Thank you, dear Mr. Millais, for giving it to me. There is nothing in the world I have, or can ever have, that I shall value half as much. I think you know this, although I can find so few words to tell you how grateful I am."

The Times ran an editorial calling for Charles Dickens to be buried in Westminster Abbey. This was readily accepted and on 14th June, 1870, his oak coffin was carried in a special train from Higham to Charing Cross Station. The family travelled on the same train and they were met by a plain hearse and three coaches. Only four of his children, Charles Culliford Dickens, Mamie Dickens, Kate Dickens Collins and Henry Fielding Dickens attended the funeral. George Augustus Sala gave the number of mourners as fourteen.

Dickens's last will and testament, dated 12th May 1869 was published on 22nd July. As Michael Slater has commented: "Like Dickens's novels, his last will has an attention-grabbing opening" as it referred to his mistress, Ellen Ternan. It stated: "I give the sum of £1,000 free of legacy duty to Miss Ellen Lawless Ternan, late of Houghton Place, Ampthill Square, in the county of Middlesex." It is assumed that he made other, more secret, financial arrangements for his mistress. For example, it is known that she received £60 a year from the house he owned in Houghton Place. According to her biographer, she was now a "woman approaching middle age, in delicate health, solitary and inured to dependence on a man who could give her neither an honourable position nor even steady companionship."

The total estate amounted to over £90,000. "I give the sum of £1,000 free of legacy duty to my daughter Mary Dickens. I also give to my said daughter an annuity of £300 a year, during her life, if she shall so long continue unmarried; such annuity to be considered as accruing from day to day, but to be payable half yearly, the first of such half yearly payments to be made at the expiration of six months next after my decease. If my said daughter Mary shall marry, such annuity shall cease; and in that case, but in that case only, my said daughter shall share with my other children in the provision hereinafter made for them."

Charles Dickens used the will to highlight the role that Georgina Hogarth had played in his life: "I give to my dear sister-in-law Georgina Hogarth the sum of £8,000 free of legacy duty. I also give to the said Georgina Hogarth all my personal jewellery not hereinafter mentioned, and all the little familiar objects from my writing-table and my room, and she will know what to do with those things. I also give to the said Georgina Hogarth all my private papers whatsoever and wheresoever, and I leave her my grateful blessing as the best and truest friend man ever had."

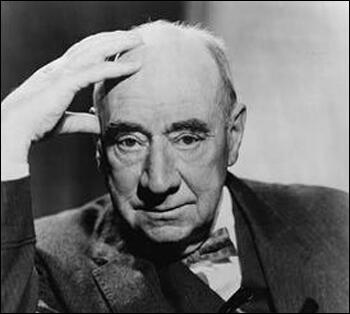

On this day in 1917 historian Eric Hobsbawm, the son of a Jewish tradesman, was born in Alexandria, Egypt. After the First World War ended his parents moved to Austria. By the time he was thirteen, both his parents had died. He went to live with his aunt in Berlin.

When Adolf Hitler gained power in 1933, what was left of Hobsbawn's family moved to London. He later recalled: "In Germany there wasn't any alternative left. Liberalism was failing. If I'd been German and not a Jew, I could see I might have become a Nazi, a German nationalist. I could see how they'd become passionate about saving the nation. It was a time when you didn't believe there was a future unless the world was fundamentally transformed."

Hobsbawn did well in his English school and he won a scholarship to study history at King's College, Cambridge. While a student joined the Communist Party of Great Britain. He also edited the student weekly, Granta.

On the outbreak of the Second World War Hobsbawn joined the British Army. Despite speaking German, French, Spanish and Italian fluently he was turned down for intelligence work. He served with the Royal Engineers and later with the Educational Corps. MI5 created a file on Hobsbawm in 1942. Although he was cleared of “suspicion of engaging in subversive activities or propaganda in the army”, he was prevented from joining the Intelligence Corps. At the end of the war, in July 1945, an MI5 officer noted: “As he is known to be in contact with communists I should be interested to see all his personal correspondence”.

After the war Hobsbawm returned to Cambridge University where he completed a PhD on the Fabian Society. In 1947 he became a lecturer at Birkbeck College. Hobsbawn joined E. P. Thompson, Christopher Hill, Rodney Hilton, A. L. Morton, Raphael Samuel, George Rudé, John Saville, Dorothy Thompson, Edmund Dell, Victor Kiernan and Maurice Dobb in forming the Communist Party Historians' Group. In 1952 members of the group founded the journal, Past and Present. Over the next few years the journal pioneered the study of working-class history.

John Saville later wrote: "The Historian's Group had a considerable long-term influence upon most of its members. It was an interesting moment in time, this coming together of such a lively assembly of young intellectuals, and their influence upon the analysis of certain periods and subjects of British history was to be far-reaching."

During this period MI5 and police special branch officers tapped and recorded his telephone calls, intercepted his private correspondence and monitored his contacts. MI5 said the object of keeping checks on Hobsbawm was “to establish the identities of his contacts and to unearth overt or covert intellectual Communists who may be unknown to us”.

Hobsbawm's first book,Primitive Rebels, was published in 1959. This was followed by The Age of Revolution (1962), Labouring Men (1964), Industry and Empire (1968), Bandits (1969). In 1969 Hobsbawn co-wrote Captain Swing with George Rudé.

Eric Hobsbawm, unlike most of his friends, remained a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain. However, he did protest against the Soviet invasion of Hungary. MI5 files show that at a meeting at the party’s headquarters at King Street, at the end of 1956, Hobsbawm, Christopher Hill and Doris Lessing agreed to write a letter attacking the party leadership’s “uncritical support … to Soviet action in Hungary”, a reference to the crushing of the uprising there. That support, the letter explained, was “the undesirable culmination of years of distortion of facts”. Hill, who left the party a year later, used the phrase “the crimes of Stalin” at the meeting, according to the MI5 report. The party’s paper, The Daily Worker, refused to publish the letter.

Hobsbawm also diagreed with the actions of the Soviet Union in Czechoslovakia in 1968. According to Richard Norton-Taylor: "Hobsbawm never left the Communist party but the MI5 files show he argued with the party leadership so strongly that it considered dismissing him, according to transcripts of MI5’s bugged conversations."

In 1970 he became professor of history at Birkbeck College, a post he held for twelve years. Other books by Hobsbawn include Revolutionaries (1973), The Age of Capital (1975), History of Marxism (1978), Workers (1984), The Age of Empire (1987), Nations and Nationalism (1990), The Age of Extremes (1994), On History (1997), Uncommon People (1998), The New Century (1999), Interesting Times (2002) and Globalisation, Democracy and Terrorism (2008).

Eric Hobsbawm died on 1st October, 2012.

On this day in 1927 Victoria Woodhull, died. Victoria Claflin, the sixth of ten children, was born in Homer, Ohio on 23rd September, 1838. When Victoria was a child the family was forced to leave Homer after her father, Reuben Claflin, was accused of an insurance fraud. She received very little education and spent most of her childhood with her family's travelling medicine show.

At the age of fifteen Victoria married Canning Woodhull. The following year she gave birth to Byron Woodhull. Over the next few years she earned a living by telling fortunes, selling patent medicines and performing a spiritualist act with her sister, Tennessee Claflin.

Canning Woodhull was an alcoholic and in 1864 she divorced him and two years later married Colonel James Blood. In 1868 Victoria Woodhull moved to New York City where she became friends with millionaire railroad magnate, Cornelius Vanderbilt. With Vanderbilt's backing, the enterprising sisters went into business as Wall Street's first female stockbrokers. The sisters made a large amount of money and this enabled them to publish their own journal, Woodhull and Claflin's Weekly.

Woodhull's journal was used to promote women's suffrage and other radical causes such as the 8 hour work day, graduated income tax, and profit sharing. Woodhull also exposed fraudulent activities that were then rampant in the stock market. Woodhull became the leader of the International Working Men's Association (the First International) in New York City and in 1872 controversially became the first person to publish The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Frederick Engels.

In May 1872 Victoria Woodhull was nominated as the presidential candidate of the Equal Rights Party. Although laws prohibited women from voting, there was nothing stopping women from running for office. Woodhull suggested that Frederick Douglass should become her running partner but he declined the offer.

During the campaign Woodhull called for the "reform of political and social abuses; the emancipation of labor, and the enfranchisement of women". Woodhull also argued in favour of improved civil rights and the abolition of capital punishment. These policies gained her the support of socialists, trade unionists and women suffragists. However, conservative leaders of the American Woman Suffrage Association, such as Susan Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, were shocked by some of her more extreme ideas and supported Horace Greeley in the election.

Friends of President Ulysses Grant decided to attack Victoria Woodhull's character and she was accused of having affairs with married men. It was also alleged that Victoria's previous husband was an alcoholic and her her sister, Utica Claflin, took drugs. Woodhull became convinced that Henry Ward Beecher was behind these stories and decided to fight back. She now published a story in the Woodhull and Claflin's Weekly that Beecher was having an affair with a married woman.

Victoria Woodhull was arrested and charged under the Comstock Act for sending obscene literature through the mail and was in prison on election day. (Woodhull's name did not appear on the ballot because she was one year short of the Constitutionally mandated age of thirty-five.) Over the next seven months Woodhull was arrested eight times and had to endure several trials for obscenity and libel. She was eventually acquitted of all charges but the legal bills forced her into bankruptcy.

In 1878 Woodhull moved to England. She continued to campaign for women's rights and in 1895 she established the Humanitarian newspaper. In 1897 she gave up publishing and moved to Bredon's Norton, where she built a village school and became a champion for education reform in English schools.

On this day in 1954 Joseph N. Welch helps to bring down Senator Joseph McCarthy. Welch challenged Roy Cohn to provide McCarthy's list of 130 Communists or subversives in defense plants "before sundown". McCarthy said that if Welch was so concerned about persons aiding the American Communist Party, he should check on a man in his Boston law office named Fred Fisher, who had once belonged to the National Lawyers Guild (NLG). Welch had privately discussed the matter with Fisher beforehand and the two agreed Fisher should not participate in the hearings.

Welch dismissed Fisher's association with the NLG as a youthful indiscretion and attacked McCarthy for naming the young man before a nationwide television audience without prior warning or previous agreement to do so: "Until this moment, Senator, I think I have never really gauged your cruelty or your recklessness. Fred Fisher is a young man who went to the Harvard Law School and came into my firm and is starting what looks to be a brilliant career with us. ... Little did I dream you could be so reckless and so cruel as to do an injury to that lad... It is, I regret to say, equally true that I fear he shall always bear a scar needlessly inflicted by you. If it were in my power to forgive you for your reckless cruelty I would do so. I like to think I am a gentleman, but your forgiveness will have to come from someone other than me.

When McCarthy tried to renew his attack, Welch interrupted him: "Senator, may we not drop this? We know he belonged to the Lawyers Guild ... Let us not assassinate this lad further, Senator. You've done enough. Have you no sense of decency, sir? At long last, have you left no sense of decency?"

Welch's TV performance turned the tide of public and press opinion against McCarthy overnight. The following night, Edward Murrow, in his TV programme, See It Now commented: "Mr. Welch, a veteran of the courtroom, was near to tears because a young man whom he liked, knew, trusted and worked with had been attacked. It is safe to assume, I think, that had Mr. Welch never heard of Mr. Fisher, his emotion - his anger - would have been considerably less. It seems to this reporter that there is a widespread tendency on the part of all human beings to believe that because a thing happens to a stranger, or to someone far away, it doesn't happen at all.

Despite modern communications it is difficult to communicate over any considerable distance, unless there be some common denominator of experience. You cannot describe adequately the destruction of a city, or a reputation, to those who have never witnessed either. You cannot describe adequately aerial combat to a man who has never had his feet off the ground. We can read with considerable equanimity of the death of thousands by war, flood or famine in a far land, and that intelligence jars us rather less than a messy automobile accident on the corner before our house. Distance cushions the shock. This is the way humans behave and react. Their emotions are not involved, their anger or their fear not aroused until they approach near to danger, doubt, deceit or dishonesty. If these manifestations do not affect us personally, we seem to feel that they do not exist.... It must be presumed, I think, that Counsel Welch is familiar, very familiar, with Senator McCarthy's record and tactics. He had, up to yesterday, maintained an almost affable, avuncular relationship with the Senator. He was pressing Mr. Cohn - but by Mr. Cohn's admission doing him no personal injury - when Senator McCarthy delivered his attack upon Mr. Fisher, at which point Counsel Welch reacted like a human being."

McCarthy lost the chairmanship of the Government Committee on Operations of the Senate. He was now without a power base and the media lost interest in his claims of a communist conspiracy. As one journalist, Willard Edwards, pointed out: "Most reporters just refused to file McCarthy stories. And most papers would not have printed them anyway." Although some historians claim that this marked the end of McCarthyism, others argue that the anti-communist hysteria in the United States lasted until the end of the Cold War.

On this day in 1964 Max Aitken, Lord Beaverbrook, died of cancer at Cherkley Court. William Maxwell Aitken, the third son and fifth member of a family of ten children, whose father, William Cuthbert Aitken (1834–1913), was a Presbyterian minister, was born in Maple, Ontario, on 25th May 1879. His biographer, David George Boyce, has argued: "Until he was sixteen he attended the local school, where he was described as a bright but idle boy and (an epithet which he was to relish later in life) mischievous. He was also sensitive and nervous and harboured a fear of death that remained with him."

In 1895 he failed his examination for Dalhousie University after refusing to sit the Latin and Greek papers. He moved to Chatham where he became local correspondent of The Montreal Star and an agent for the Great West Life insurance company. He then moved to St John, with the intention of being a lawyer. However, he eventually worked as a full-time insurance agent, but this did not turn out to be a very successful venture.

In 1900 Aitken moved to Halifax, a rapidly growing town that was developing an infrastructure of gas, telephones, and tramways. Aitken became friendly with John Fitzwilliam Stairs, a financial expert and highly successful businessman. With the help of Stairs he began dealing on the stock market. He also bought and sold companies as well as investing in Cuba and Puerto Rico.

On 29th January 1906 he married Gladys Henderson Drury. The authors of Beaverbrook: A Life (1992) pointed out: "The bride was Gladys Drury, a girl universally liked and universally thought beautiful. She was very young, eighteen to his twenty-six, with long auburn hair and green eyes... The Drurys were a cut above the Aitkens. The bride's distinguished father, Lieutenant-Colonel (later Brigadier-General) Charles Drury, had lately been appointed to a coverted post demanding social as well as military accomplishments; he was the first Canadian to command the Halifax garrison after the British Army relinquished its responsibilities." Their first child, Janet, was born on 9th July 1908.

In 1909 the cement industry in Canada was in grave trouble. Overproduction and the establishment of new companies meant that the producers had to cut their prices to the point where they found it very difficult to be profitable. Aitken began buying these companies and merging them into one company he called Canada Cement. By September 1909 he had a near monopoly of the cement industry.

Sir Sandford Fleming, Canada's leading industrialists, accused of Aitken of corrupt business activities, claiming that he had bought the merged companies for some $14,000,000, whereas he had told the shareholders that he had paid over $27,000,000, and issued himself with bonds and shares far in excess of the companies' true cost. The case received a great deal of publicity and after paying back a large sum of money to shareholders, he decided to move to London.

Aitken soon became friends with Andrew Bonar Law, a leading figure in the Conservative Party. As David George Boyce has pointed out: "The two men got on well, despite their very different individual temperaments: both had Scots-Canadian connections, both were sons of the manse, both were businessmen." Aitken gave Bonar Law business advice. A.J.P. Taylor claimed in his book, Beaverbrook (1972) that Bonar Law "probably benefited to the extent of some £10,000 a year."

In November 1910 Law recommended him as a possible parliamentary candidate for Ashton under Lyne. Aitken agreed to fight the seat and with plenty of money to spend on publicity he was able to organise a good campaign. A local reporter claimed: "He set a new fashion in electioning... He planned the election exactly as though it were some great new business enterprise." Aitken won the seat by 196 votes.

Aitken rarely spoke in the House of Commons. However, he became a leading political figure because of his financial contributions to Conservative Party. Aitken bought Cherkley Court, a large house near Leatherhead, which became a centre of political gatherings. Aitken began to appear in political cartoons. David Low commented: "He was not a ready-made subject for caricature. Large head, boyish face, full cheeks, wide forehead, unruly hair, small nose with peculiar curve, wide grin belied by sharp light eye, slight small figure, short neck, high shoulders, neat extremities, hairy hands, undistinguished dark blue suit. The whole thing lay in the wide grin belied by the sharp eye."

In 1911 Aitken and several senior figures in the party put up £40,000 to buy The Globe, the oldest of London's seven evening newspaper. Founded in 1803 and printed on pink paper. According to the authors of of Beaverbrook: A Life (1992): "The Globe, though unsuccessful, gave Aitken useful practice in dealing with advertisers and editors, like a young fighter testing his skills in the amateur ring before turning professional." Aitken also purchased shares in The Daily Express.

Aitken remained close to Andrew Bonar Law and supported him in his bid to oust Arthur Balfour as party leader. In October 1911 Aitken wrote to his friend, Rudyard Kipling: "Bonar Law has come to the conclusion that Balfour's position is very dangerous. Bonar is loyal to his leader, but admits that he may owe his allience elsewhere in the near future." Balfour resigned on 8th November.

At a meeting of Conservative MPs on 13th November, it was discovered that it seemed to be a contest between Joseph Chamberlain and Walter Long. Bonar Law only had 40 firm supporters. Balfour's secretary wrote to his boss during the leadership contest: "Much intrigue has been at work.... Bonar Law's own methods are open to much criticism. In this struggle I am told that he has been run by Max Aitken, the little Canadian adventurer who sits for Ashton-under-Lyne. Aitken practically owns the Daily Express and the Daily Express has run Bonar Law for the last two days for all it is worth. The real Bonar Law appears to be a man of boundless ambition untempered by any particular nice feelings. It is a revelation."

With the help of Aitken, Bonar Law became the new leader. It has been argued that Bonar Law's accession to the leadership probably saved the unity of the Conservative Party. David Low has argued: "He (Aitken) dislocated the pattern, ruptured the continuity, pushed traditions and institutions around. His loyalty was placed where and when, in his arbitrary judgment, at any given time, it was deserved. He certainly did not conform to anything. He was nobody but himself. Two simple ideas underlaid the success story in Canadian business: mergers and the exploitation of new values there from. His subsequent story in British politics had run on the same lines. His main political operations had been all mergers, achieved or attempted, of people, parties and/or policies." H. G. Wells suggested: "If ever Max ever gets to Heaven, he won't last long. He will be chucked out for trying to pull off a merger between Heaven and Hell after having secured a controlling interest in key subsidiary companies in both places, of course."

The outbreak of the First World War in August 1914 gave Aitken the opportunity to show his organisational skills. On 3rd October, 1914, 30,000 Canadian troops sailed for England. They camped on Salisbury Plain while they received training before being sent to the Western Front. Aitken became honorary lieutenant-colonel and was appointed to help the Canadian Overseas Expeditionary Force. He was instrumental in creating the Canadian War Records Office in London and arranged for stories about Canadian forces appearing in newspapers. In January 1916 Aitken published the first volume of Canada in Flanders.

Valentine Browne, 6th Earl of Kenmare, met Aitken during this period: "He was not very tall but sturdy enough. His head was large and round - eyes far apart. He was dressed in the uniform of a Canadian colonel, wearing no strap on his belt and boots laced up the centre. Not a military figure from a Guardsman's point of view but singularly engaging from a young man's angle. The approach to youth is delicate. Some have a sensitive touch and they alone always know how to get response out of mankind... Max Aitken had this touch."

In 1916 Aitken purchased a controlling interest in The Daily Express. However, he kept this a secret as he disapproved of the way the war was being pursued and used his newspaper to undermine the power of Herbert Asquith. He was also involved in the plot to remove Asquith from power. He later recalled that it was the most important thing that he had done in politics: "The destruction of the Asquith Government which was brought about by an honest intrigue. If the Asquith government had gone on, the country would have gone down."

The consequences of the Battle of the Somme in the summer of 1916 put further pressure on Asquith. Colin Matthew has commented: "The huge casualties of the Somme implied a further drain on manpower and further problems for an economy now struggling to meet the demands made of it... Shipping losses from the U-boats had begun to be significant... Early in November 1916 he called for all departments to write memoranda on how they saw the pattern of 1917, the prologue to a general reconsideration of the allies' position."

At a meeting in Paris on 4th November, 1916, David Lloyd George came to the conclusion that the present structure of command and direction of policy could not win the war and might well lose it. Lloyd George agreed with Maurice Hankey, secretary of the Imperial War Cabinet, that he should talk to Andrew Bonar Law, the leader of the Conservative Party, about the situation. Bonar Law remained loyal to Asquith and so Lloyd George contacted Aitken instead and told him about his suggested reforms.

On 18th November, Aitken lunched with Bonar Law and put Lloyd George's case for reform. He also put forward the arguments for Lloyd George becoming the leader of the coalition. He later recalled in his book, Politicians and the War (1928): "Once he had taken up war as his metier he seemed to breathe its true spirit; all other thoughts and schemes were abandoned, and he lived for, thought of and talked of nothing but the war. Ruthless to inefficiency and muddle-headedness in his conduct, sometimes devious, if you like, in the means employed when indirect methods would serve him in his aim, he yet exhibited in his country's death-grapple a kind of splendid sincerity."

Together, Aitken, Lloyd George, Bonar Law and Edward Carson, drafted a statement addressed to Asquith, proposing a war council triumvirate and the Prime Minister as overlord. On 25th November, Bonar Law took the proposal to Asquith, who agreed to think it over. The next day he rejected it. Further negotiations took place and on 2nd December Asquith agreed to the setting up of "a small War Committee to handle the day to day conduct of the war, with full powers", independent of the cabinet. This information was leaked to the press by Carson. On 4th December The Times used these details of the War Committee to make a strong attack on Asquith. The following day he resigned from office. On 7th December George V asked Lloyd George to form a second coalition government.

Aitken expected David Lloyd George, the new prime minister, to appoint him as President of the Board of Trade, but this did not happen. Instead he was granted a peerage and as Lord Beaverbrook he became a leading political figure in Britain. However, Beaverbrook remained critical of the government and in 1917 he helped finance The Imperialist, a newspaper run by the right-wing MP, Noel Pemberton Billing. His biographer, Geoffrey Russell Searle, has pointed out that "Billing campaigned for a unified air service, helped force the government to establish an air inquiry, and advocated reprisal raids against German cities. He also became adept at exploiting a variety of popular discontents."

The journal also claimed the existence of a secret society called the Unseen Hand. As Ernest Sackville Turner, the author of Dear Old Blighty (1980) has pointed out: "One of the great delusions of the war was that there existed an Unseen (or Hidden, or Invisible) Hand, a pro-German influence which perennially strove to paralyse the nation's will and to set its most heroic efforts at naught... As defeat seemed to loom, as French military morale broke and Russia made her separate peace, more and more were ready to believe that the Unseen Hand stood for a confederacy of evil men, taking their orders from Berlin, dedicated to the downfall of Britain by subversion of the military, the Cabinet, the Civil Service and the City; and working not only through spiritualists, whores and homosexuals."

Lord Beaverbrook decided against supporting The Imperialist after he was told that he was to become the first Minister of Information, responsible for Allied propaganda in Allied and neutral countries. Lord Northcliffe became Director of Propaganda, with the job of controlling propaganda in enemy countries.

On 9th February, 1918, Noel Pemberton Billing launched a savage attack on Lord Beaverbrook in The Imperialist. "His name for the moment is Beaverbrook; and was Max Aitken, which some people believe is derived from an original name of Isaacs. If this is true, he belongs to the same tribe as our Lord Chief Justice Ambassador, and the ruling and representing of Britain has become a close tribal affair ... It seems, if they have accepted Lord Beaverbrook as Minister of Propaganda, they have walked into the first trap baited by a banking organisation most to be feared by those who wish this country well."

After the war Beaverbrook concentrated on his newspaper business. He told the readers of the Daily Express that his newspaper was "the prophet of equal opportunity and the unrelenting opponent of that system of preferred chances which gives one man an unfair opportunity over a more competent rival." In 1919 the newspaper's circulation was under 400,000; but by 1930 it was 1,693,000 and in 1937 it stood at 2,329,000, the largest circulation of any newspaper in the British Isles.

Beaverbrook, who developed ideas pioneered by Alfred Harmsworth and the Daily Mail, turned the Daily Express into the most widely read newspaper in the world. Beaverbrook also founded the Sunday Express (1921) and in 1929 purchased the Evening Standard. Beaverbrook's biographer, David George Boyce, has tried to explain the success of his newspaper: "This was because of its popular, aggressive tone, but also its optimism, enthusiasm, and claim to speak for those who were, like Beaverbrook himself, determined to stand up for themselves and take control of their own lives. There were also lively features, and all this in the style of the new journalism. Beaverbrook, like his great predecessor Northcliffe, was careful to keep up with the new technology and to experiment with layout. Unlike Northcliffe he did not use stunts to promote sales: his success was based on his belief in the importance of the words on the page, and to this end he hired first-rate staff - financial writers like Francis Williams and the great cartoonist David Low (whom Beaverbrook brought to the Evening Standard in 1927)."

Beaverbrook was a strong supporter of appeasement in the late 1930s and his newspaper praised Neville Chamberlain and the Munich Agreement, with the Daily Express claiming on 22nd September 1938 that Britain had made no pledge to protect the frontiers of Czechoslovakia. In March 1939 he denied that Chamberlain had made any absolute guarantee to Poland, and when war broke out in September, Beaverbrook's political judgement was severely damaged.

After a meeting with Winston Churchill on 10th May, 1940, Beaverbrook threw his energy behind the war effort. Churchill appointed Beaverbrook minister of aircraft production, knowing how good Beaverbrook was at inspiring and driving staff. Beaverbrook took over responsibility for repairs to damaged aircraft, as well as production of new planes. On 2nd August he became a member of the war cabinet.

Other posts held by Beaverbrook during the Second World War included Minister of Supply (1941-2), Minister of War Production (1942), and Lord Privy Seal (1943-45). He eventually clashed with Ernest Bevin. The historian, A.J.P. Taylor, has argued: "Beaverbrook had a fatal weakness. He had no political following. He commanded no wide popularity in parliament or in the country. He was in his own words, a court favourite, who owed his position to Churchill's friendship. The protecting hand was now withdrawn. Beaverbrook's defeat was cloaked by the excuse of physical illness. No doubt more lay behind. Churchill could not go into battle against Bevin. Besides he did not want to. Beaverbrook was as enthusiastic for Soviet Russia and the Second Front as any factory worker. Churchill resisted these enthusiasms. This brought Beaverbrook down. He left the government."

In 1947 Lord Beaverbrook told the Royal Commission on the Press he ran his papers for propaganda purposes, and that he was unwilling to allow his editors to oppose policies that were "dear to his heart". He argued: "No paper is any good at all for propaganda unless it has a thoroughly good financial position. So we worked very hard to build up a commercial position on that account". The commission later reported that Beaverbrook picked staff who shared his views and policies. This included his views on the European Common Market (EEC) which he complained was "an American device to put us alongside Germany. As our power was broken and lost by two German wars, it is very hard on us now to be asked to align ourselves with those villains".

His biographer, David George Boyce, points out: "He argued that free enterprise was the way forward, but he was not a consistently right-wing thinker: the cold war was, he thought, unnecessary. He still clung to the ideas of imperial unity, freedom from foreign entanglements, and a distant relationship with the United States of America, all of which though not necessarily mistaken - were out of touch with the times. He remained the empire crusader, opposing British acceptance of an American loan in 1947, and, above all, against the British application to join the European Common Market (EEC)."