Chat Moss

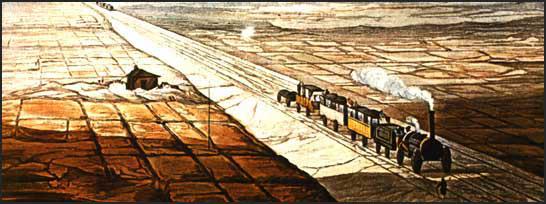

Chat Moss is a vast peat bog lying north of the River Irwell and five miles west of Manchester. Almost twelve square miles in area with the widest part lying across the direct route between Liverpool and Manchester.

All the early route surveys of proposed railway routes between Liverpool and Manchester made detours to avoid Chat Moss. The owners of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway were therefore surprised when their chief engineer, George Stephenson, argued that it was possible to cross the peat bog.

Members of the House of Commons also had doubts about Stephenson's proposal and this was one of the main reasons why Parliament rejected the Liverpool & Manchester company's plans for a railway in 1824. Stephenson was unwilling to change his proposed route and two years later Parliament gave in and passed the bill given permission for the building of the railway.

John Dixon was recruited as resident engineer and together they devised a strategy for crossing Chat Moss. George Stephenson believed that it would be possible to use a floating raft to support the four mile trackbed across the bog. At first a footpath of heather was laid along the proposed route. This worked well and so it was broadened out to carry a contractor's line on which boys pushed the one ton wagons of construction material.

Over 200 men were employed to lay drains on each side of the track area. Although this worked in the shallower parts, it made no impact on the deeper areas of the bog. George Stephenson now had to change his plan and the drain was replaced with barrels and casks jointed together and coated with clay to create a form of pipe. This improved the situation but at an area known as the Blackpool Hole, the barrels continued to rise to the surface.

It was suggested to Stephenson that he should abandon his strategy and instead build a viaduct across the bog. Stephenson refused to accept defeat, and no doubt influenced by the large amounts of money already used at Chat Moss, decided to keep trying. One of the men on the site, Robert Stannard, suggested a plan that would produce a firm but pliable track. Stephenson accepted Stannard's idea of timber laid in herring-bone fashion. This was combined with moss, heather and brushwood hurdles.

Progress was slow and the track across Chat Moss was not finished until December, 1829. On 1st January 1830, the Rocket successfully hauled a one-ton carriage train across the four mile section.

Primary Sources

(1) Samuel Smiles described Chat Moss in his book Lives of the Engineers (1899)

Chat Moss is an immense peat bog of about twelve square miles. Unlike the bogs or swamps of Cambridge and Lincolnshire, which consist principally of soft mud or silt, this bog is a vast mass of spongy vegetable pulp. The spagni, or bog-mosses, cover the entire area; one year's growth rising over another, the older growths not entirely decaying. the peculiar character of the Moss has prevented an insuperable difficulty in the way of reclaiming it by any system of extensive drainage.

(2) Thomas Harrison, an opponent of the proposed Liverpool & Manchester Railway, criticised Stephenson's plan to cross Chat Moss.

It is ignorance almost inconceivable. It is perfect madness. Every part of the scheme shows that this man has applied himself to a subject of which he has no knowledge, and to which he has no science to apply.

(3) On 25th April, 1825, George Stephenson gave evidence to the House of Commons committee looking into the proposed Liverpool & Manchester Railway. Edward Alderson, criticised Stephenson's plans for Chat Moss.

Everybody knows that the iron sinks immediately on its being put upon the surface. I have heard of culverts, which have been put upon the Moss, which after been surveyed the day before, have the next morning disappeared. As fast as one is added, the lower one sinks! There is nothing, it appears, except long sedgy grass, and a little soil to prevent it sinking into the shades of eternal night.

(4) On 23rd December, 1837 George Stephenson made a speech in Birmingham about building the railway over Chat Moss.

After working for weeks and weeks we went on filling in without the slightest apparent effect. Even my assistants began to feel uneasy and to doubt the success of the scheme. The directors, too, spoke of it as a hopeless task, and at length they became seriously alarmed, so much so, indeed, that a board meeting was held on Chat Moss to decide whether I should proceed any further. they had previously taken the opinion of other engineers, who reported unfavourably. We had to go on. An immense outlay had been incurred and a great loss would have been occasioned had the scheme been then abandoned.

(5) Samuel Smiles later interviewed George Stephenson and Robert Stephenson about how they managed to overcome Chat Moss.

George Stephenson's idea was, that a railroad might be made to float upon the bog. As a ship, or raft, capable of sustaining heavy loads floated in water, so in his opinion, might a light road be floated upon a bog. The first thing done was to form a footpath of heather along the proposed road, on which a man might walk without risk of sinking. A single line of temporary railway was then laid down, formed of ordinary cross-bars about 3 feet long and an inch square, with holes punched through them at the ends and nailed down to temporary sleepers. Along this way ran the waggons in which were conveyed the materials requisite to form the permanent road. These waggons carried about a ton each, and were propelled by boys running behind them along the narrow iron rails. The boys became so expert that they would run the 4 miles at the rate of 7 or 8 miles an hour without missing a step.

(6) Samuel Smiles, Life of George Stephenson (1875)

During the progress of these works the most ridiculous rumours were set afloat. The drivers of the stage-coaches who feared for their jobs, brought the most alarming intelligence into Manchester from time to time, that "Chat Moss was blown up!" "Hundred of men and horses had sunk and the works were completely abandoned!" The engineer himself was declared to have swallowed up in the Serbonian bog; and "railways were at an end for ever!"