The Blutcher

In 1813 George Stephenson became aware of attempts by William Hedley and Timothy Hackworth, at Wylam Colliery, to develop a locomotive. Stephenson successfully convinced the owners of Killingworth Colliery to allow him to try to produce a steam-powered machine. By 1814 he had constructed a locomotive that could pull thirty tons up a hill at 4 mph (6.5 kpm). Stephenson called his locomotive, The Blutcher (the name of a general in the Prussian Army, who had just helped Britain to defeat Napoleon).

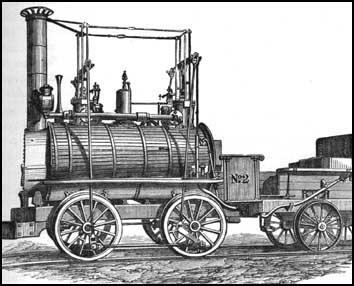

Stephenson's locomotive, with its two vertical cylinders let into the boiler, from the pistons of which rods drove the gears, was very similar to those produced at the time by John Blenkinsop, William Hedley and Timothy Hackworth. Where The Blutcher differed from these other locomotives was that the gears did not drive the rack pinions but the flanged wheels. Stephenson's machine was therefore the first successful flanged-wheel adhesion locomotive. Stephenson continued to try and improve his locomotive and in 1815 he changed the design so that the connecting rods drove the wheels directly. These wheels were coupled together by a chain.

Over the next few years, The Blutcher was constantly being improved by Stephenson. In an attempt to try and get up more power and to lessen the noise of the escaping steam Stephenson turned the exhaust into the chimney and produced what became known as the blast pipe.

The owners of the colliery were impressed with Stephenson's achievements and in 1819 he was given the task of building a eight mile railroad from the newly opened colliery at Hetton-le-Hole to the River Wear at Sunderland. When this railroad was opened in 1822, Stephenson's Blutcher was kept very busy.

Stephenson also used the Blutcher to convince Edward Pearse the major shareholder of the Stockton & Darlington company to build a locomotive, rather than a horse railway. Stephenson told Pease that "a horse on an iron road would draw ten tons for one ton on a common road". Stephenson added that the Blutcher locomotive that he had built at Killingworth was "worth fifty horses". That summer Edward Pease took up Stephenson's invitation to visit Killingworth Colliery. When Pease saw The Blutcher at work he realised George Stephenson was right and offered him the post as the chief engineer of the Stockton & Darlington company.