George Dolby

George Dolby was born in 1831. He became a theatre manager but in 1866 Chappell Publishers employed Dolby to work for Charles Dickens in his reading tour of the country. Dolby later recalled: "Though I had known Mr. Dickens for some time previously, this was the first occasion on which I came into contact with him in a business matter ; and there was naturally a feeling of constraint which might have made our first interview tedious but for that geniality, that antidote to reserve, which formed one of his chief characteristics." Dickens insisted that they should be accompanied by William Henry Wills, his assistant at All the Year Round. According to Dolby this was "not only for companionship, but to enable him the more easily to conduct the magazine during his absence from the metropolis." Dickens shook his hand and said: "I hope we shall like each other on the termination of the tour as much as we seem to do now."

According to Claire Tomalin, the author of Dickens: A Life (2011): "Gorge Dolby, a big man, full of energy, optimism and know-how, and talkative, with a stammer he bravely disregarded. He was thirty-five, just married, a theatre manager out of work and keen to take on the running of Dickens' next reading tour. He was sent by Chappell, the music publishers who were setting up the tour, and he won Dickens's confidence at once, and quickly became a friend... They laughed and joked together like boys, and enjoyed the small rituals of travel."

The first tour lasted for three months and included London, Liverpool, Edinburgh, Manchester, Glasgow, Birmingham, Aberdeen and Portsmouth. "That Chappell had no reason to rue their bargain was shown by the fact that on the completion of the tour the gross receipts amounted to nearly £5,000. Such a success had never been known in any similar enterprise; and it was all the more gratifying as Mr. Dickens had, with that consideration for the masses which ever characterized his actions, stipulated, at the commencement of the engagement, that shilling seat-holders should have as good accommodation as those who were willing to pay higher sums for their evening's enjoyment." Dickens had insisted: "I have been the champion and friend of the working man all through my career, and it would be inconsistent, if not unjust, to put any difficulty in the way of his attending my readings."

In his book, Charles Dickens as I Knew Him (1885), Dolby recorded that Dickens usually performed readings from Christmas Carol, Pickwick Papers and David Copperfield: "The scenes in which appeared Tiny Tim (a special favourite with him) affected him and his audience alike, and it not infrequently happened that he was interrupted by loud sobs from the female portion of his audience (and occasionally, too, from men) who, perhaps, had experienced the inexpressible grief of losing a child. So artistically was this reading arranged, and so rapid was the transition from grave to gay, that his hearers had scarcely time to dry their eyes after weeping before they were enjoying the fun of Scrooge's discovery of Christmas Day, and his conversation from his window with the boy in the court below. All these points told with wonderful effect, the irresistible manner of the reader enhancing a thousand times the subtle magic with which the carol is written."

Dickens wrote to John Forster on 21st February, 1867: "The enthusiasm has been unbounded. On Friday night I quite astonished myself; but I was taken so faint afterwards that they laid me on a sofa, at the hall for half an hour. I attribute it to my distressing inability to sleep at night, and to nothing worse. Everything is made as easy to me as it possibly can be. Dolby would do anything to lighten the work, and does everything."

By the end of the tour Dickens became very close friends with Dolby. Michael Slater, the author of Charles Dickens (2009), has argued that the two men "quickly developed an excellent rapport". Dickens told Dolby about his relationship with Ellen Ternan. It was Dolby's job to arrange meetings between Dickens and his mistress when he was touring. In one letter to his manager, Dickens commented: "In answer to your enquiry to Nelly - I do not think I shall be here until Wednesday in the ordinary course. But I can be in town on Tuesday at from 5 to 6, and will dine at the Posts with you, if you like."

Peter Ackroyd pointed out in Dickens (1990): "Dolby was a tall, bald, thick-set man with a loud laugh, and a supply of humorous stories matched only by theatrical gossip. Precisely the kind of man, in other words, that Dickens liked... The forced proximity of Dolby and Dickens, over a number of years, did nothing to destroy the true friendship which grew up between them - both of them professional men, both of them funny and observant. In addition, and most important of all to Dickens, Dolby remained punctilious and trustworthy."

James T. Fields tried to encourage Dickens to carry out a reading tour of the United States. On 22nd May, 1866, he wrote to reject the suggestion: "Your letter is an excessively difficult one to answer, because I really do not know that any sum of money that could be laid down would induce me to cross the Atlantic to read. Nor do I think it likely that any one on your side of the great water can be prepared to understand the state of the case. For example, I am now just finishing a series of thirty readings. The crowds attending them have been so astounding, and the relish for them has so far out gone all previous experience, that if I were to set myself the task, 'I will make such or such a sum of money by devoting myself to readings for a certain time,' I should have to go no further than Bond Street or Regent Street, to have it secured to me in a day. Therefore, if a specific offer, and a very large one indeed, were made to me from America, I should naturally ask myself, 'Why go through this wear and tear, merely to pluck fruit that grows on every bough at home?' It is a delightful sensation to move a new people; but I have but to go to Paris, and I find the brightest people in the world quite ready for me. I say thus much in a sort of desperate endeavor to explain myself to you. I can put no price upon fifty readings in America, because I do not know that any possible price could pay me for them. And I really cannot say to any one disposed towards the enterprise, 'Tempt me,' because I have too strong a misgiving that he cannot in the nature of things do it."

Mary Dickens, was one of those advising Dickens not to go on a reading tour of America. As she explained in Charles Dickens by His Eldest Daughter (1874): "For many years my father's public readings were an important part of his life, and into their performance and preparation he threw the best energy of his heart and soul, practising and rehearsing at all times and places. The meadow near our home was a favorite place, and people passing through the lane, not knowing who he was, or what doing, must have thought him a madman from his reciting and gesticulation. The great success of these readings led to many tempting offers from the United States, which, as time went on, and we realized how much the fatigue of the readings together with his other work were sapping his strength, we earnestly opposed his even considering."

In January 1867 they began a four month tour that included Ireland and Wales. In Dublin it was feared that Dickens would encounter political protests. Dolby explained: "As a precautionary measure, the public-houses were ordered to be closed from Saturday evening, March 16th (St. Patrick's Eve), till the following Tuesday morning. The public buildings had strong forces within their walls, and the troops were all confined to barracks. Notwithstanding all this, the city life went on as if no danger were anticipated, and hospitality played - as it always does in Dublin - a leading part in the affairs of life. At dinner, Mr. Dickens expressed a wish to make an inspection of the city, and as some of the guests at our friend's house had to do the same thing officially, his desire was very easily gratified. Returning to our hotel for a change of costume, we sallied forth in the dead of the night on outside cars, and under police care, to make a tour of the city; and so effectual were the precautions taken by the Government, that in a drive from midnight until about two o'clock in the morning, we did not see more than about half a dozen persons in the streets, with the exception of the ordinary policemen on their beats. Several arrests of suspected persons had been made in the night, and some of these became our fellow-travellers in the Irish mail on our return to England."

Charles Dickens eventually changed his mind about the American tour and on 13th June, 1867, he wrote to James T. Fields: "I have this morning resolved to send out to Boston in the first week in August, Mr. Dolby, the secretary and manager of my readings; He is profoundly versed in the business of these delightful intellectual feasts, and will come; straight to Ticknor and Fields, and will hold solemn council with them, and will then, go to New York, Philadelphia, Hartford, Washington, etc, and see the rooms for himself and make his estimates.... We mean to keep all this strictly secret, as I beg of you to do, until I finally decide for or against. I am beleaguered by every kind of speculator, in such things on your side of the water; and it is very likely they would take the rooms over our heads - to charge us heavily for them - or would set on foot unheard - of devices for buying up the tickets, etc., if the probabilities oozed out."

After George Dolby returned to London an agreement was signed by Dickens with his American publishers, Ticknor and Fields. Dolby explained: "In making this calculation the expenses have been throughout taken on the New York scale, which is the dearest; as much as twenty per cent, has been deducted for management, including Mr. Dolby's commission; and no credit has been taken for any extra payment on reserved seats, though a good deal of money is confidently expected from this source. But, on the other hand, it is to be observed that four Readings (and a fraction over) are supposed to take place every week, and that the estimate of receipts is based on the assumption that the audiences are, on all occasions, as large as the rooms will reasonably hold. So considering eighty Readings, we bring out the net profit of that number remaining to me, after payment of all charges whatever, as £15,500."

9th November, 1867, Dickens and Dolby left Liverpool on board the Cuba and following a rough passage, arrived in Boston ten days later. James T. Fields later recalled: "A few of his friends, under the guidance of the Collector of the port, steamed down in the custom-house boat to welcome him. It was pitch dark before we sighted the Cuba and ran alongside. The great steamer stopped for a few minutes to take us on board, and Dickens's cheery voice greeted me before I had time to distinguish him on the deck of the vessel. The news of the excitement the sale of the tickets to his readings had occasioned had been earned to him by the pilot, twenty miles out. He was in capital spirits over the cheerful account that all was going on so well, and I thought he never looked in better health. The voyage had been a good one, and the ten days' rest on shipboard had strengthened him amazingly he said. As we were told that a crowd had assembled in East Boston, we took him in our little tug and landed him safely at Long Wharf in Boston, where carriages were in waiting. Rooms had been taken for him at the Parker House, and in half an hour after he had reached the hotel he was sitting down to dinner with half a dozen friends, quite prepared, he said, to give the first reading in America that very night, if desirable. Assurances that the kindest feelings towards him existed everywhere put him in great spirits, and he seemed happy to be among us."

Dolby reported that there was a great demand for tickets: "The scene in Boston was as nothing compared with the scene in New York, for the line of purchasers exceeded half a mile in length. The line commenced to form at ten o'clock on the night prior to the sale, and here were to be seen the usual mattresses and blankets in the cold streets, and the owners of them vainly endeavouring to get some sleep - an impossibility under the circumstances; for, leaving the bitter cold out of the question, the singing of songs, the dancing of breakdowns, with an occasional fight, made night hideous, not only to the peaceful watcher, but to the occupants of the houses in front of which the disorderly band had established itself. These ladies and gentlemen had my sincere sympathies; for my hotel was within fifty yards of the scene of action, and the shouting, shrieking, and singing of the crowd suggested the night before an execution at the Old Bailey, when executions were still public."

The first performance was at the Tremont Temple in Boston. According to Dolby: "The Tremont Temple had to be tested acoustically, a process that was always gone through in every new room in which he read. The process was very simple, and was conducted in the following manner. Mr. Dickens used to stand at his table, whilst I walked about from place to place in the hall or theatre, and a conversation in a low tone of voice was carried on between us during my perambulations. The hall having been pronounced perfect, a long walk was undertaken; and after a four o'clock dinner (as in England) and a sleep of an hour or so, we went to the Tremont Temple for the great event of the day."

Dolby pointed out in his book, Charles Dickens as I Knew Him (1885), that after he finished his reading from Christmas Carol "a dead silence seemed to prevail - a sort of public sigh as it were - only to be broken by cheers and calls, the most enthusiastic and uproarious, causing Mr. Dickens to break through his rule, and again presenting himself before his audience, to bow his acknowledgments." Dolby continued, "The reading being concluded, and the most enthusiastic signs of approval having been accorded to the reader in the form of recall after recall, Mr. Dickens indulged in his usual rub down, changing his dress-clothes for those he habitually wore when not en grande tenue, and a few of his most intimate friends were admitted into his dressing-room to offer their congratulations on the result of the evening's experiences."

Charles Dickens spent the first six weeks of the tour reading in Boston and New York City. Dolby claimed that Dickens "always regarded Boston as his American home, inasmuch as all his literary friends lived there". Weeks seven to eight was devoted to Philadelphia and Brooklyn. During weeks nine and eleven Dickens read in Baltimore and Washington. By this time Dickens was in poor health and his intended visits to Chicago and St Louis were cancelled. The reading tour was proving to be lucrative and on 15th January, 1868, Dolby paid in £10,000 to Dickens's bank.

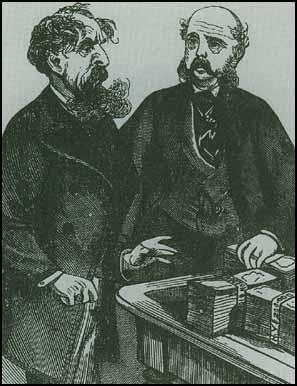

present you with $300,000, the result of your lectures in America. DICKENS: "What only $300,000? Is that all I have made out of these penurous Yankees, after all my abuse of them?

Cartoon in American Newspaper (April, 1868)

By this time Dickens was in poor health and his intended visits to Chicago and St Louis were cancelled. Dickens took a brief rest before resuming his tour and in March visited Syracuse, Rochester, Buffalo, Albany, Portland and Maine. By this time he was suffering from the old problem of a swollen left foot. He told Mamie Dickens that he was mainly on a liquid diet. He listed his daily intake as being a tablespoonful of rum in a tumbler of fresh cream, a pint of champagne, an egg beaten up in sherry (twice) and soup, last thing at night. He added: "I don't eat more than half a pound of solid food in the whole four-and-twenty hours."

On 22nd April, Dickens left for Liverpool on board the Russia . The New York Tribune reported: "It was a lovely day - a clear blue sky overhead - as he (Charles Dickens) stood resting on the rail, chatting with his friends, and writing an autograph for that one, the genial face all aglow with delight, it was seemingly hard to say the word 'Farewell,' yet the tug-boat screamed the note of warning, and those who must return to the city went down the side. All left save Mr. Fields. 'Boz' held the hand of the publisher within his own. There was an unmistakable look in both faces. The lame foot came down from the rail, and the friends were locked in each other's arms. Mr. Fields then hastened down the side, not daring to look behind. The lines were cast off. A cheer was given for Mr. Dolby, when Mr. Dickens patted him approvingly upon the shoulder, saying, 'Good boy'. Another cheer for Mr. Dickens, and the tug steamed away."

Dolby reported after the tour: "The original scheme embraced eighty Readings in all, of which seventy-six were actually given. Taking one city with another, the receipts averaged $3,000 each Reading, but as small places such as Rochester, New Bedford, and many others of the same class did not exceed $2,000 a night, the receipts in New York and Boston (where the largest sum was taken), far exceeded the $3,000 mentioned above. The total receipts were $228,000, and the expenses were $39,000, including hotels, travelling expenses, rent of halls, etc., and, in addition, a commission of 5% to Messrs. Ticknor and Fields on the gross receipts in Boston. The advertising expenses were very trifling - a preliminary advertisement announcing the sale of tickets being. all that was necessary. The hotels for Mr. Dickens, myself, and occasionally Mr. Osgood, and our staff of three men averaged $60 a day."

Dolby continued to see Dickens on a regular basis after he returned to London. He recorded in his book, Charles Dickens as I Knew Him (1885): "The last time I saw Charles Dickens, was on Thursday, June 2, 1870, when I made one of my weekly visits to the office. Getting there just in time for luncheon, I found him greatly absorbed in business matters, and although the same old greeting was awaiting me, it was painfully evident that he was suffering greatly both in mind and body. During luncheon, many plans for the future were talked of between us, amongst others an early visit to Gad's Hill, where we were to make a thorough inspection of the new conservatory, and several other improvements, in which both of us were greatly interested. But he was very busy that afternoon, and I rose to leave earlier than usual. Then came our final parting, though we neither of us thought of it as such. We shook hands across the office-table, and after a hearty grasp of the hand, and the words from him, 'next week then,' I turned to go, though with a troubled sense that I was leaving my chief in great pain. He rose from the table, and followed me to the door; I noticed the difficulty of his walk, and the pained look on his face, but was unwilling to speak, so without another word on either side, we parted."

Charles Dickens died on 8th June, 1870. The traditional version of his death was given by his official biographer, John Forster. He claimed that Dickens was having dinner with Georgina Hogarth at Gad's Hill Place when he fell to the floor: "Her effort then was to get him on the sofa, but after a slight struggle he sank heavily on his left side... It was now a little over ten minutes past six o'clock. His two daughters came that night with Mr. Frank Beard, who had also been telegraphed for, and whom they met at the station. His eldest son arrived early next morning, and was joined in the evening (too late) by his youngest son from Cambridge. All possible medical aid had been summoned. The surgeon of the neighbourhood (Stephen Steele) was there from the first, and a physician from London (Russell Reynolds) was in attendance as well as Mr. Beard. But human help was unavailing. There was effusion on the brain."

George Dolby went to Gad's Hill Place as soon as he heard the news: "I went to Gad's Hill at once, where I was most kindly and gently received by Miss Dickens and Miss Hogarth, who told me the story of his last moments. The body lay in the dining-room, where Mr. Dickens had been seized with the fatal apoplectic fit. They asked me if I would go and see it, but I could not bear to do so. I wanted to think of him as I had seen him last. I went away from the house, and out on to the Rochester road. It was a bright morning in June, one of the days he had loved; on such a day we had trodden that road together many and many a time. But never again, we two, along that white and dusty way, with the flowering hedges over against us, and the sweet bare sky and the sun above us. We had taken our last walk together."

Dolby also arranged reading tours for Mark Twain. The novelist described Dolby as "large and ruddy, full of life and strength and spirits, a tireless and energetic talker, and always overflowing with good nature and bursting with jollity." Twain also enjoyed his great fund of anecdotes and stories. Another acquaintance said he could be extremely noisy and was not "over-refined" and used to entertain his friends by standing on his head upon a chair.

George Dolby died in a paupers' hospital, the Fulham Infirmary, in 1900.

Primary Sources

(1) George Dolby, Charles Dickens as I Knew Him (1885)

That Chappell had no reason to rue their bargain was shown by the fact that on the completion of the tour the gross receipts amounted to nearly £5000. Such a success had never been known in any similar enterprise; and it was all the more gratifying as Mr. Dickens had, with that consideration for the masses which ever characterized his actions, stipulated, at the commencement of the engagement, that shilling seat-holders should have as good accommodation as those who were willing to pay higher sums for their evening's enjoyment; " for," said he, "I have been the champion and friend of the working man all through my career, and it would be inconsistent, if not unjust, to put any difficulty in the way of his attending my readings."

(2) George Dolby, Charles Dickens as I Knew Him (1885)

A private rehearsal was given on March 18th, at Southwick Place, Hyde Park, in a furnished house which Mr. Dickens had taken for the season. This audience consisted of the members of his family, and Mr. Robert Browning, Mr. Wilkie Collins, Mr. Charles Fechter, Mr. John Forster, Mr. Arthur Chappell, Mr. Charles Kent, and myself. It is hardly necessary to say that the verdict was unanimously favourable. Everybody was astonished by the extra-ordinary ease and fluency with which the patter of the "Cheap Jack " was delivered, and the subtlety of the humour which pervaded the whole presentation. To those present, the surprise was no less great than the results were pleasing; indeed, it is hard to see how it could well have been otherwise, for seldom, and but too seldom in the world's history, do we find a man gifted with such extraordinary powers, and, at the same time, possessed of such a love of method, such will, such energy, and such a capacity for taking pains. An example of this is the interesting fact that, although to many of his hearers at that eventful rehearsal of "Doctor Marigold" it was the first time it had been read, Mr. Dickens had, since its appearance as a Christmas number, only three months previously, adapted it as a

(3) George Dolby, Charles Dickens as I Knew Him (1885)

The Reading of the 14th of April having been given in the afternoon, we had thus an evening to ourselves, and a consultation was held as to the best means of whiling away the hour. Mr. Dickens's tastes being inclined to theatre or circus, we repaired to the circus; for, appreciative as he was of the actor's art, he had an immense admiration for the equestrian, and never failed to visit a circus whenever the chance presented itself. The admiration he felt and the pleasure he derived from witnessing legitimate feats of horsemanship were, however, frequently marred by the indiscretions of the clown, who, as soon as it became known that Mr. Dickens was amongst the audience, would improvise some stupidly contrived pun having reference to his name or books, or would perpetrate an atrocity in the shape of a conundrum.

(4) George Dolby, Charles Dickens as I Knew Him (1885)

On my arrival in Glasgow on the morning following the Edinburgh Reading, I found that every ticket was

sold for all the available parts of the city hall, even to the shilling places; and that the agents, in the hope

of saving the public from visiting the hall on a fruitless errand, and desiring to avoid a recurrence of those

expressions of discontent which had been lavishly bestowed upon them on a former occasion, had, a caution characteristic of their nationality, issued bills and advertisements to the effect that "no money would be taken at the doors." Notwithstanding the notice, however, large crowds collected, to be again disappointed.

The Readings on this occasion were the "Christmas Carol" and the "Trial from Pickwick." The former, next to "David Copperfield," was the most popular with the author... The scenes in which appeared Tiny Tim (a special favourite with him) affected him and his audience alike, and it not infrequently happened that he was interrupted by loud sobs from the female portion of his audience (and occasionally, too, from men) who, perhaps, had experienced the inexpressible grief of losing a child. So artistically was this reading arranged, and so rapid was the transition from grave to gay, that his hearers had scarcely time to dry their eyes after weeping before they were enjoying the fun of Scrooge's discovery of Christmas Day, and his conversation from his window with the boy in the court below. All these points told with wonderful effect, the irresistible manner of the reader enhancing a thousand times the subtle magic with which the carol is written.

(5) George Dolby, Charles Dickens as I Knew Him (1885)

During the dinner orderlies were continually arriving at our host's house with dispatches, giving such details as could be collected of the probable "rising" that night, and it was clear that had any such movement taken place, the authorities would have proved fully equal to the occasion.

As a precautionary measure, the public-houses were ordered to be closed from Saturday evening, March 16th (St. Patrick's Eve), till the following Tuesday morning. The public buildings had strong forces within their walls, and the troops were all confined to barracks. Notwithstanding all this, the city life went on as if no danger were anticipated, and hospitality played - as it always does in Dublin - a leading part in the affairs of life.

At dinner, Mr. Dickens expressed a wish to make an inspection of the city, and as some of the guests at our friend's house had to do the same thing officially, his desire was very easily gratified. Returning to our

hotel for a change of costume, we sallied forth in the dead of the night on outside cars, and under police

care, to make a tour of the city; and so effectual were the precautions taken by the Government, that in a drive from midnight until about two o'clock in the morning, we did not see more than about half a dozen persons in the streets, with the exception of the ordinary policemen on their beats. Several arrests of suspected persons had been made in the night, and some of these became our fellow-travellers in the Irish mail on our return to England.

Contrary to our fears, the political disturbances had done no harm to Mr. Dickens's reputation in his

capacity as a reader, for our audiences were quite up to the average of our visits to Ireland in quiet times and what at the outset looked most embarrassing, turned out a really enjoyable time, which was rendered not the less pleasant by a demonstrative reception in Belfast, where no trace of Fenianism could be discovered.

(6) Charles Dickens, letter to James T. Fields (13th June, 1912)

I have this morning resolved to send out to Boston in the first week in August, Mr. Dolby, the secretary and manager of my readings; He is profoundly versed in the business of these delightful intellectual feasts, and will come; straight to Ticknor and Fields, and will hold solemn council with them, and will then, go to New York, Philadelphia, Hartford, Washington, etc, and see the rooms for himself and make his estimates.... We mean to keep all this strictly secret, as I beg of you to do, until I finally decide for or against. I am beleaguered by every kind of speculator, in such things on your side of the water; and it is very likely they would take the rooms over our heads - to charge us heavily for them - or would set on foot unheard - of devices for buying up the tickets, etc., if the probabilities oozed out.

(7) George Dolby, Charles Dickens as I Knew Him (1885)

As it was then about six in the morning, I took advantage of the "early call " - so unceremoniously given - to get up, take a walk on deck, and catch my first glimpse of New York City, and its beautiful harbour, of which I had heard so much. The sun was shining brilliantly, and, as it was Sunday, the ships at the wharves were displaying their best bunting, in honour of the day. What a sight the city presents under these circumstances! Flags of every nationality, streaming out in bold relief against the clear blue sky, which gives a power and tone to the bright colours that no other sky in the world (in my experience) can produce.

The city looked as if it were fast asleep, but it was not - and never is! The New Yorker is ever on the alert, for business or pleasure, and this being a pleasure day, as all Sundays are in New York, the streets were found, even at that early hour in the morning, to be quite alive with people hurrying to meet a steamer, or to catch a train in Jersey City, or elsewhere, to carry them off to the pretty country around Englefield, or some other equally charming spot, or to take them up the famed Hudson River - one of the most beautiful in the world.

The steamer was brought to at the wharf, as quietly as if she had a fear of waking up her living freight, most of whom were fast asleep, and, in some cases, snoring, in the comfortable state-rooms; for on

these vessels the passenger can remain in his room as long as his inclination dictates, and when he does get up, he has all the luxury of an hotel to fly to for his creature comforts.

(8) George Dolby, Charles Dickens as I Knew Him (1885)

The fixing of the date for the first Reading, viz., Monday, December 2, 1867, seemed to increase that excitement tenfold; and especially when it was known that the first sale of tickets would take place at the publishing house of Messrs. Ticknor and Fields, No. 12, Tremont Street, Boston, on Monday morning, November 18th, at nine o'clock. Vague rumours were in circulation, and fears were entertained, that in the great excitement the general public would get no chance of buying tickets, for that the speculators, not only of Boston, but of New York, were making their plans to purchase all the tickets they could get, in the hope of selling them at a premium. These rumours caused a considerable amount of pressure to be put upon every one connected with the enterprise, by friends and acquaintances who wanted to have tickets beforehand, or at all events to have their places marked before the sale commenced; and so great was the demand in this respect, that Mr. Fields had on his list, on the night prior to the sale, orders for nearly 250 tickets for each of the first four Readings, and every one else connected in the firm was in a proportionately similar position. As such a course would have been obviously unfair to those persons who had no private influence with the "powers," I most distinctly declined to allow the sale to be conducted in any but a fair and straightforward manner, and decided that tickets for the course of the first four Readings only were to be sold the first day, and if any were left they were to be sold as required on the following days.

In addition to the private demand for tickets, I was beset in every conceivable manner, not only through

the post, but by personal application from people who were, or who pretended to be, afflicted in a variety of ways, by. deafness, blindness, paralysis ; and all were anxious to avoid the trouble and annoyance of purchasing their tickets in the usual course. Strange to say, in consequence of their various afflictions they all wanted front seats, a demand it was impossible' to comply with. I came to the conclusion that the afflicted ones formed a large proportion of the population of Boston.

(9) George Dolby, Charles Dickens as I Knew Him (1885)

The scene in Boston was as nothing compared with the scene in New York, for the line of purchasers

exceeded half a mile in length. The line commenced to form at ten o'clock on the night prior to the sale, and here were to be seen the usual mattresses and blankets in the cold streets, and the owners of them vainly endeavouring to get some sleep - an impossibility under the circumstances; for, leaving the bitter cold out of the question, the singing of songs, the dancing of breakdowns, with an occasional fight, made night hideous, not only to the peaceful watcher, but to the occupants of the houses in front of which the disorderly band had established itself.

These ladies and gentlemen had my sincere sympathies; for my hotel was within fifty yards of the scene of action, and the shouting, shrieking, and singing of the crowd suggested the night before an execution at the Old Bailey, when executions were still public.

(10) George Dolby, Charles Dickens as I Knew Him (1885)

The reception accorded to Mr. Dickens, in making his appearance at the little table, had never been

surpassed by the greetings he was in the habit of receiving in Edinburgh and Manchester, and was

calculated to unnerve a man of even greater moral courage than he was possessed of. Those who were

not applauding and waving handkerchiefs were seriously "taking in" the appearance of the man to whom they owed so much, which up to this time they knew only by the bad photographs in the shop

windows.... When everything was quiet, and the deafening cheers which had greeted his appearance had subsided, a terrible silence prevailed, and it seemed a relief to his hearers when he at last commenced the Reading.

(11) George Dolby, Charles Dickens as I Knew Him (1885)

When at last the Reading of "The Carol" was finished, and the final words had been delivered, and "so, as Tiny Tim observed, God bless us every one," a dead silence seemed to prevail - a sort of public sigh

as it were - only to be broken by cheers and calls, the most enthusiastic and uproarious, causing Mr. Dickens to break through his rule, and again presenting himself before his audience, to bow his acknowledgments.

(12) George Dolby, Charles Dickens as I Knew Him (1885)

The Reading being concluded, and the most enthusiastic signs of approval having been accorded to the

Reader in the form of recall after recall, Mr. Dickens indulged in his usual " rub down," changing his dress-clothes for those he habitually wore when not en grande tenue, and a few of his most intimate friends were admitted into his dressing-room to offer their congratulations on the result of the evening's experiences.

(13) The New York Tribune (23rd April, 1868)

It was a lovely day - a clear blue sky overhead - as he (Charles Dickens) stood resting on the rail, chatting with his friends, and writing an autograph for that one, the genial face all aglow with delight, it was seemingly hard to say the word 'Farewell,' yet the tug-boat screamed the note of warning, and those who must return to the city went down the side.

All left save Mr. Fields. "Boz" held the hand of the publisher within his own. There was an unmistakable look in both faces. The lame foot came down from the rail, and the friends were locked in each other's arms. Mr. Fields then hastened down the side, not daring to look behind. The lines were cast off.

A cheer was given for Mr. Dolby, when Mr. Dickens patted him approvingly upon the shoulder, saying,

"Good boy." Another cheer for Mr. Dickens, and the tug steamed away.

(14) George Dolby, Charles Dickens as I Knew Him (1885)

We had undergone so much in the way of demonstrations and ovations in America that, certainly for a time, Mr. Dickens was desirous of avoiding anything of the kind, feeling in want of rest and retirement after the fatigues and excitement of our campaign, and for this reason his arrival home was conducted in the manner described.

It came to the knowledge of Miss Hogarth and Miss Dickens, that had the Chief arrived at his own

station of Higham, the villagers had intended to take the horse out of his carriage, and to drag him to his

own house. So, in order to avoid this, he arranged to have his carriage meet him at Gravesend, and to drive from there. The villagers, not to be done out of their anticipated pleasure, turned out on foot, and in their market carts and gigs ; and escorting Mr. Dickens on the road, kept on giving him shouts of welcome, the houses along the road being decorated with flags. His own servants wanted to ring the alarm bell in the little belfry at the top of the house, but that idea was speedily crushed. The following day being Sunday, the bells of his own church rang out a peal after the morning service in honour of his return.

Meeting Mr. Dickens on the following Thursday named, I was surprised to find all traces of his late fatigues and ill-health had disappeared, and, to quote the words of his own medical man, he was looking

"seven years younger." The sea air, and the four days' rest at Gad's Hill, favoured by beautiful weather, had brightened him so that he looked as if he had never had a day's illness in his life.

(15) George Dolby, Charles Dickens as I Knew Him (1885)

The original scheme embraced eighty Readings in all, of which seventy-six were actually given. Taking one city with another, the receipts averaged $3,000 each Reading, but as small places such as Rochester, New Bedford, and many others of the same class did not exceed $2,000 a night, the receipts in New York and Boston (where the largest sum was taken), far exceeded the $3,000 mentioned above. The total receipts were $228,000, and the expenses were $39,000, including hotels, travelling expenses, rent of halls, etc., and, in addition, a commission of 5 % to Messrs. Ticknor and Fields on the gross receipts in Boston. The advertising expenses were very trifling - a preliminary

advertisement announcing the sale of tickets being. all that was necessary. The hotels for Mr. Dickens, myself, and occasionally Mr. Osgood, and our staff of three men averaged $60 a day.

(16) George Dolby, Charles Dickens as I Knew Him (1885)

The last time I saw Charles Dickens, was on Thursday, June 2, 1870, when I made one of my weekly visits to the office. Getting there just in time for luncheon, I found him greatly absorbed in business matters, and although the same old greeting was awaiting me, it was painfully evident that he was suffering greatly both in mind and body.

During luncheon, many plans for the future were talked of between us, amongst others an early visit

to Gad's Hill, where we were to make a thorough inspection of the new conservatory, and several other

improvements, in which both of us were greatly interested. But he was very busy that afternoon, and

I rose to leave earlier than usual. Then came our final parting, though we neither of us thought of it

as such. We shook hands across the office-table, and after a hearty grasp of the hand, and the words from him, "next week then," I turned to go, though with a troubled sense that I was leaving my chief in great pain. He rose from the table, and followed me to the door; I noticed the difficulty of his walk, and

the pained look on his face, but was unwilling to speak, so without another word on either side, we parted.

An affair of business took me from London immediately afterwards, and I was prevented from calling at

the office on the following Thursday, at the usual time. As it was understood between us that whenever I did not do this, a future meeting should be arranged by post, I meant to write him a letter on the following day. But that letter was never written, for I read in the newspapers the next morning that my friend and chief was dead.

I went to Gad's Hill at once, where I was most kindly and gently received by Miss Dickens and Miss

Hogarth, who told me the story of his last moments. The body lay in the dining-room, where Mr. Dickens had been seized with the fatal apoplectic fit. They asked me if I would go and see it, but I could

not bear to do so. I wanted to think of him as I had seen him last. I went away from the house, and out on to the Rochester road. It was a bright morning in June, one of the days he had loved; on such a day we had trodden that road together many and many a time. But never again, we two, along that white and dusty way, with the flowering hedges over against us, and the sweet bare sky and the sun above us. We had taken our last walk together.