On this day on 6th October

On this day in 1829, the Rainhill Trials began. Eight conditions were laid down for the locomotives that entered the competition. This included the rule that the maximum weight was to be six tons. All wheels had to be sprung and the cost of the locomotive had to be less than £550. The gross weight of the train was stated to be not less than three times the engine's weight. To qualify for the first prize the locomotive had to reach speeds of 10 mph (16 kpm).

On the first day over 10,000 people turned up to watch the competitors. The locomotives had to run twenty times up and down the track at Rainhill which made the distance roughly equivalent to a return trip between Liverpool and Manchester. Ten locomotives were originally entered for the competition but only five turned up.

On the third day the Rocket covered 35 miles in 3 hours 12 minutes. Hauling 13 tons of loaded wagons, the Rocket averaged over 12 mph. On one trip it reached 25 mph and on a locomotive-only run, 29 mph. After studying all the evidence, the three judges, John Rastrick, Nicholas Wood and John Kennedy, awarded the £500 first prize to the owners of the locomotive. The contract to produce locomotives for the Liverpool & Manchester Railway went to the Robert Stephenson Company at Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

On this day in 1863 the anti-child labour campaigner, Frances Trollope, died.

Frances (Fanny) Milton, the middle child of William Milton (1743–1824), and his first wife, Mary Gresley Milton, was born in Bristol on 10th March 1779. Her father was the vicar of Heckfield, Hampshire. According to Pamela Neville-Sington the author of Frances Trollope (1998): "William Milton... preferred inventing gadgets to saving souls, and his most important idea was the creation of a tidal bypass to control the water levels of the Avon, allowing ships to sail in and out of Bristol more freely. Of his three children, Frances - or Fanny as she was known to her friends and family - resembled her father most. Like him, she was incapable of sitting still and doing nothing if there was a problem to be solved or a situation to be improved. Without the guidance of her mother, who died when Fanny was only five or six years old, she also learned to be self-reliant. Together these traits - initiative, tenacity, and independence of mind - were to give her the courage, strength, and ability to overcome the many crises which she would have to face in her lifetime; but they also made her sometimes act rashly, without thinking, and thus court disaster."

In 1800 her father married Sarah Partington. Fanny did not like her stepmother and along with her sister, Mary, decided to live with her brother Henry in London. When she was twenty-nine she met the barrister, Thomas Trollope. He considered her to have a petite figure, a pleasant face, and "the neatest foot and ankle" on the dance floor. After a year's courtship, they married on 23rd May 1809. Her first child died soon after being born. Over the next nine years Fanny gave birth to six more children: Thomas, Henry, Arthur, Anthony, Cecilia, and Emily.

Thomas later recalled: "My mother's disposition… was of the most genial, cheerful, happy, enjoué nature imaginable… and to any one of us a tête-à-tête with her was preferable to any other disposal of a holiday hour". By contrast, Thomas Anthony, was a harsh father and used to punish the children for small misdemours by pulling their hair. It has been speculated that his agrressive behaviour was caused by the effects of calomel, a mercury-based drug which he took for chronic migraine.

Thomas Trollope eventually took over a 160 acre farm. He had no experience in farming and he was soon heavily in debt. Thomas Trollope's son, Anthony Trollope, said that everything his father touched ended in failure: "But the worse curse to him of all was a temper so irritable that even those he loved the best could not endure it. We were all estranged from him, and yet I believed he would have given his heart's blood for any of us. His life as I knew it was one long tragedy."

In 1827 Frances Trollope and her two daughters spent time visiting Frances Wright at Nashoba, a community in the backwoods of Tennessee dedicated to the education and emancipation of slaves. According to her biographer, Pamela Neville-Sington: "Fanny thought it Henry's best chance to find a good prospect in life; she also hoped to ease the family's financial burdens back home while escaping her husband's dreadful temper. She left her two remaining sons, Tom and Anthony, at home to continue their education. When her friend's utopian dream turned out to be a malaria-ridden swamp, Fanny decamped and headed up the Mississippi to Cincinnati, Ohio."

While living in Cincinnati, Frances Trollope opened up what has been called "America's first shopping mall", the Cincinnati Bazaar. The venture was a disaster and see ended up bankrupt and ill with malaria. She began spending a great deal of time with a young French artist, Auguste Hervieu, who, despite the gossip, was in fact nothing more than a devoted friend. In August 1831 she returned to England.

The following year she published Domestic Manners of the Americans (1832). The book was an attack of what she believed was the hypocrisy of the Americans. "With one hand hoisting the cap of liberty, and with the other flogging their slaves. You will see them one hour lecturing their mob on the indefeasible rights of man, and the next driving from their homes the children of the soil, whom they have bound themselves to protect by the most solemn treaties."

Thomas Trollope, still heavily in debt, died in 1835. Frances Trollope decided to become a novelist. Her novels were very popular and it was not long before she was able to pay off her husband's debts. Trollope believed that novels should deal with important social issues. Her novel, Jonathan Jefferson Whitlaw, was about the evils of slavery, and The Vicar of Wrexhill tackled the subject of church corruption.

In 1839 Frances Trollope decided to write a novel on young factory workers. She had become interested in the subject after reading a copy of the book on the life of Robert Blincoe in 1832. Before writing the novel she carried out a fact-finding mission to Manchester. Frances Trollope was accompanied by the French artist, Auguste Hervieu, who had been commissioned to produce illustrations for the book. Trollope and Hervieu spent several weeks visiting factories and having meeting with people involved in the campaign for factory reform. This included Richard Oastler, Joseph Raynor Stephens and John Doherty, the editor of The Poor Man's Advocate .

The first part of Michael Armstrong: Factory Boy, was published in 1840. Frances Trollope was the first woman to issue her novels in monthly parts. Costing one shilling a month, it was also the first industrial novel to be published in Britain. The conservative The Athenaeum, gave it a hostile reception and compared Trollope to James Rayner Stephens: "The most probable immediate effect of her pennings and her pencillings will be the burning of factories and the plunder of property of all kinds. The Rev. James Rayner Stephens has recently been sentenced to eighteen months imprisonment for using seditious and inflammatory language. The author of Michael Armstrong deserves as richly to have eighteen months in Chester Gaol. But if the text be bad, still worse are the plates that illustrate it. What, for instance, must be the effect of the first picture in No. V1 (mill children competing with pigs for food), on the heated imaginations of our great manufacturing towns, figuring as they do in every book-seller's window."

Richard Henry Horne, the author of A New Spirit of the Age (1844) also disliked her novels: "Mrs Trollope takes a strange delight in the hideous and revolting. Nothing can exceed the vulgarity of Mrs Trollope's mob of characters. We have heard it urged on behalf of Mrs. Trollope that her novels are, at all events, drawn from life. So are sign paintings."

Of her novels, The Widow Barnaby and The Widow Married were the most successful. Pamela Neville-Sington has argued: "In her later novels, whether set in a cathedral town, a country estate, or London's West End, Fanny combined witty social commentary with strong and often melodramatic plots. At its best, Fanny's writing is subtle and well observed and, even in the most far-fetched romance, she is able to convey with great skill the foibles and follies of human nature - and of English manners in particular. She astutely aimed to hit the somewhat lowbrow taste of the circulating library."

By the time Frances Trollope died in Florence on 6th October 1863, aged eighty-four, she had written forty books. Her sons, Anthony Trollope (1815-1882) and Thomas Adolphus Trollope (1810-1892), were both successful writers.

in Francis Trollope's Michael Armstrong (1840)

On this day in 1900 Ethel Mannin, the eldest of the three children of Robert Mannin, a postal worker and Edith Gray, a farmer's daughter, was born in Clapham on 11th October 1900. Her father was a socialist and encouraged her to have a career. In her biography she recalled: "My father does not care how I achieve happiness so long as I achieve it."

Her parents sent her to a local private school: In Confessions and Impressions (1930) she recalled: "The school called itself a preparatory school, hut for what it could possibly prepare anyone it would be impossible to say.... I was so agonisingly shy and timid that I was fair game for the older children's teasing. A group of the older girls would amuse themselves by tormenting me until I would say a funny little obscene word...here was also a girl of about twelve whom I thought both grown-up and beautiful, immeasurably beyond me, but she had nothing but contempt for me. She wore petticoats with wide lace to them, and knickers with coloured ribbons run through. She was fond of doing high kicks-presumably to show off this seductive lingerie. I knew a curious quickening of the senses at the sight of her; she was a dashing and lovely being infinitely removed from me. But I have forgotten her name. I suppose that it is because I unconsciously shrink from the memory of her. She was one of my sadistic persecutors."

As a young girl she began writing stories and the first of these appeared in the Lady's Companion in 1910. In 1915 she won a scholarship to attend a commercial school in London. According to her autobiography, Mannin fell in love with one of her teachers: "I loved her, dear heavens, how I loved her! Once when she kissed me at the end of one of our precious lovely Saturday afternoons I walked home in a trance of ecstasy. I loved her literally so much that it hurt, and she was for me the meaning of all things that are." The teacher was also a a member of the Independent Labour Party and the Fabian Society: "Through this Miss X I learned about George Bernard Shaw, the Fabians, Jingoism, and the Independent Labour Party."

After leaving school she found employment as a typist for the advertising agency, Charles F. Higham Ltd. She later recalled "I was given twenty-three shillings a week and was tremendously excited and happy." The following year Charles Frederick Higham promoted her to the post of copywriter. "At sixteen I was writing advertisements, running two house-organs - business magazines - and when I was seventeen was publishing my own stories, articles, verses, in a monthly magazine which Higham bought and left to me to produce." Her employer was to have a great influence on her career: "I have never met anyone to equal him; for sheer individuality he stands head and shoulders above all the others. He has a dynamic quality which I have never found in the same degree of intensity in anyone else.... We are alike in that we both know what we want of life and set out to get it by the most direct route and with unfaltering determination."

Mannin began a relationship with an artist who worked for Higham. "Every evening J.S. and I would have tea together and talk... He did most of the talking. I could not talk. I listened and my young mind sucked up knowledge like a sponge absorbing water." He introduced her to the work of Thomas Paine and Robert Green Ingersoll. She later recalled: "I was deeply religious until I was sixteen, and then the artist... who was my real education, put into my hands the essays of Robert Green Ingersoll and Thomas Paine's Age of Reason, together with a Rational Press Association Annual, and I became an agnostic." He also lent her books and articles by John Stuart Mill, William Morris, Upton Sinclair, Eugene V. Debs, Graham Wallas, Robert Cunningham Graham and Peter Kropotkin. On Sunday afternoons they went to Finsbury Park and heard Tom Mann speak.

In her autobiography, Confessions and Impressions (1930), she wrote: "I loved him in the perfervid way in which I had loved my Miss X., but at fifteen I was completely sexually unawakened, and even at sixteen, towards the end of our year's association, any manifestation of love-making from him completely bewildered me. I was sixteen and he was twenty-six. I became sufficiently awakened towards the end of the friendship to want to kiss and to be kissed by him, but any caressive intimacy from him merely troubled me. It seemed queer, and I resented it a little and wished he wouldn't." He was a conscientious objector during the First World War and in 1917 he returned to New Zealand in order to avoid joining the British Army.

In 1918 she became romantically involved with John Alexander Porteus (1885–1956), who was the general manager at Highams. She later wrote that during this period that "this friendship lit by passion" was the "happiest I have ver known". On 28th November, 1919, Mannin married Porteus: "I was a very young nineteen, in spite of the experimental adventurings - too young, and too much in love, to be depressed by the dreary registry office, the cold foggy day, and the fact that we had no money and no home." Soon after her marriage she gave birth to her only child, Jean.

With a young baby to look after, Mannin now worked from home. She still wrote advertisements and edited journals for Charles Frederick Higham: "I had a retainer fee from Higham... and increased my journalistic freelance output, and wrote extensively in the provincial press... My output was tremendous; the payment was small as it always is for a beginner. Eventually she turned to novel writing and published Martha in 1923. According to one critic, the novel "elaborately plots the life of the lovechild of an unmarried woman and the price the child has to pay for the sins of the parents." This was followed by the Hunger for the Sea (1924), Sounding Brass (1925) and Pilgrims (1927). The author of The Feminist Companion to Literature in English has argued that "these are socially and politically conscious works, alert to women's oppression".

In 1929 Mannin and Porteus separated and she bought a small house in Wimbledon. Her first volume of autobiography, Confessions and Impressions appeared in 1930. According to her biographer, Beverly E. Schneller: "In 1931 she published her first book of short stories, Green Figs, and her literary success made her popular with the press, who were eager for her progressive views on sexuality, motherhood and professionalism, and marriage."

Mannin was a supporter of progressive education and sent her daughter to Summerhill School. In 1931 she published Common Sense and the Child, a book about the educational theories of A. S. Neill. She argued that "all outside compulsion is wrong... inner compulsion is the only value". Mannin also suggested that "there is no such thing as the naughty child... there are only happy children and unhappy children." She also produced a novel, Linda Shawn (1932), on the subject of progressive education. Love's Winnowing (1932) was her first openly politically novel. In 1934 she began an affair with W. B. Yeats.

Mannin was political active and had declared herself to be a socialist in her early twenties. In 1935 she joined the Independent Labour Party and contributed articles to its journal, The New Leader. In 1936 she travelled to the Soviet Union but in her book, South to Samarkland, she expressed her disillusionment with communism although she always remained firmly on the left. Mannin married Reginald Reynolds, a fellow member of the ILP on 23rd December 1938. She became friendly with Emma Goldman and her next novel, Red Rose, was based on the life of her friend.

Mannin produced seven volumes of autobiography and fourteen travel books, recording her visits to Germany, India, Morocco, Burma, Egypt, Jordan, Italy, and elsewhere. In 1958 she published her first children's books. Mannin also published several books on philosophy including Loneliness: a Study of the Human Condition (1966) and Practitioners of Love: some Aspects of the Human Phenomenon (1969).

Virginia Nicholson, the author of Among the Bohemians (2002) argues: "Ethel Mannin didn't resent the passing of youth, but she felt displaced in the post-War world of the 1950s... In old age her pleasures were correspondingly elderly - good wine, good books, and her roses. Her robust impatience with humbug remained vigorous however. She continued to travel, espoused Buddhism, and signed up to a variety of liberal causes. Passion, she felt, was for the young, but 'the unending struggle against injustice and barbarism in the world' was perennial."

In 1977 Mannin published her final memoir, Sunset over Dartmoor. In July 1984 Mannin was injured in a fall at home in Shaldon, and died of pneumonia and heart failure at Teignmouth Hospital, on 5th December 1984. During her lifetime she had published over a hundred books.

On this day in 1910 Barbara Betts, the daughter of a tax inspector, was born in Bradford on 6th October 1910. Her father was a member of the Independent Labour Party and she was converted to socialism at an early age. Castle was educated at Bradford Girls' Grammar School. Barbara wrote that "the girl's parents were all rich, and the dainty frocks that the pupils wore did credit to the school's reputation of beauty and culture throughout."

Barbara became friends with Mary Hepworth, a cash-desk girl who shared her committment to socialism. "Barbara had some sort of an intellectual battle with her father, who never felt that she did her brains justice. I think he expected too much from her at her age."

In 1929 Barbara and Mary attended the Independent Labour Party conference in Derby. That year she was the school's Labour candidate in the mock election to coincide with the 1929 General Election. Her campaign was highly impressive and one girl said that "she made you want to listen to her". She became head girl and later that year won a place at St. Hugh's College.

One of her best friends at Oxford University was Olive Shapley. She pointed out that she was very popular and had "a comet-like tail of men in pursuit". Olive later recalled: "She was small and pretty, and I think she disliked being pretty. She had these beautiful fine features, lovely little nose and beautiful skin and hair, and I think she would rather have been more dramatic looking."

In 1932 Barbara began an affair with William Mellor. As Anne Perkins, the author of Red Queen (2003) has pointed out: "Mellor was already forty-four, only six years younger than her father and exactly twice Barbara's age. He was glamorous, confident and married, with a baby son. He became her mentor, her alternative father, a man who loved her totally and compellingly." Castle later admitted "Mellor was in many ways much like my father. They were of that same bigness. He was about my father's generation, a bit younger than my father but considerably older than I was."

William Mellor introduced Castle to Stafford Cripps, the leader of the left-wing of the Labour Party. Other members of this group included Aneurin Bevan, Ellen Wilkinson, Frank Wise, Jennie Lee, Harold Laski, Frank Horrabin, Barbara Betts and G. D. H. Cole. In 1932 the group established the Socialist League.

With the rise of Adolf Hitler in Nazi Germany, Castle and Mellor became convinced that the Labour Party should establish a United Front against fascism with the Communist Party of Great Britain and the Independent Labour Party. In April 1934 Mellor had a meeting with Fenner Brockway and Jimmy Maxton, two leaders of the ILP, "to talk over ways and means of securing working-class unity". He also had meetings with Harry Pollitt, the General Secretary of the Communist Party of Great Britain.

William Mellor told Castle in 1934: "In the end I am a socialist and an agitator because I want a free world in which human relationships shall be free from the constrictions and restraints imposed by... and taboos that spring from, religious... fears. I'm a politician only because this world as it is kills individuality, destroys freedom and fetters human beings... We may have to go through hell to get there but even that wouldn't be too big a price to pay."

In the 1935 General Election Mellor, was the Labour candidate in Enfield. Mellor wrote to his mother that Barbara Castle was of great help in his campaign: "Barbara is working like a trojan and speaking like an angel." Mellor was defeated but Castle pointed out that he added five thousand to the Labour vote on "a 100% left-wing programme".

Castle continued to attack the leadership of the Labour Party for not establishing a United Front with the Independent Labour Party and Communist Party of Great Britain and along with William Mellor and Stafford Cripps established the Socialist League. This upset the leaders of the Trade Union Congress and as they still controlled the Daily Herald Mellor was warned that he was in danger of losing his job. When he refused to back-down he was sacked in March 1936.

William Mellor now established the Town and County Councillor, a journal for Labour supporters in local government. He appointed Barbara Betts, on £4 a week, as one of the journalists on the paper. He also gave work to Michael Foot, who had just left university.

In January 1937 Stafford Cripps and George Strauss decided to launch a radical weekly, The Tribune, to "advocate a vigorous socialism and demand active resistance to Fascism at home and abroad." Mellor was appointed editor and others such as Barbara Betts, Aneurin Bevan, Ellen Wilkinson, Harold Laski, Michael Foot, Winifred Batho and Noel Brailsford agreed to write for the paper.

William Mellor wrote in the first issue: "It is capitalism that has caused the world depression. It is capitalism that has created the vast army of the unemployed. It is capitalism that has created the distressed areas... It is capitalism that divides our people into the two nations of rich and poor. Either we must defeat capitalism or we shall be destroyed by it." Stafford Cripps wrote encouragingly after the first issue: "I have read the Tribune, every line of it (including the advertisements!) as objectively as I can and I must congratulate you upon a very first-rate production.''

Barbara continued to support the idea of a United Front against fascism. On 17th May 1937 she said at a meeting in Leicester: "The Socialist League stands unrepentant before the Labour movement for its action in entering into agreement with the Independent Labour Party and Communist Party of Great Britain to conduct a campaign for unity of the working class against the National Government. It stands unrepentant because it believes the workers of Great Britain cannot at this crucial moment afford the luxuries of apathy, drift and division.... Driven into a corner by the weakness of its own arguments the National Executive has resurrected as its one objection the finances of the Unity Campaign."

In October 1937, Barbara was sent by The Tribune to report on the situation in the Soviet Union. "Many a short-sighted visitor to Russia has been shocked by external evidence of poverty... But the Russians don't get alarmed. The coming of the luxurious they know is all a matter of time. And in the meanwhile they enjoy what capitalism can't offer its workers: security today, hope of abundance tomorrow... here is no shadow of slump and unemployment - only an insatiable demand for more and yet more workers."

Stafford Cripps declared that the mission of the Socialist League and The Tribune was to recreate the Labour Party as a truly socialist organization. This soon brought them into conflict with Clement Attlee and the leadership of the party. Hugh Dalton declared that "Cripps Chronicle" was "a rich man's toy". Threatened with expulsion, in May 1937 Cripps agreed to abandon the United Front campaign and to dissolve the Socialist League.

By 1938 Stafford Cripps and George Strauss had lost £20,000 in publishing The Tribune. The successful publisher, Victor Gollancz, agreed to help support the newspaper as long as it dropped the United Front campaign. When William Mellor refused to change the editorial line, Cripps sacked him and invited Michael Foot to take his place. However, as Mervyn Jones has pointed out: "It was a tempting opportunity for a 25-year-old, but Foot declined to succeed an editor who had been treated unfairly."

William Mellor now concentrated on editing the Town and County Councillor. Rumours about Mellor began to circulate. Barbara wrote to her mother claiming that Victor Gollancz was behind these stories: "Gollancz, we have every reason to believe, is spreading fairy stories about the matter all over the country, and we are helpless."

In April 1942 Mellor wrote to Barbara: "I have loved you since the first day I saw you. And after ten years - it's nearly that, sweet - rich with lovely memories and black with the recollection of my own cowardice in not following the course love set, I know now that my love is deeper, more compelling, more understanding and finer, I hope, than at any time." However, he still refused to divorce his wife and marry Barbara.

In the summer of 1942 William Mellor was told by his doctor that he had a stomach ulcer. He was told that he must take six months rest or to have an operation. Mellor felt that his job was too insecure to take too much time off so he opted for an operation. At first it seemed to go well, but then complications set in. On 8th June, 1942, two weeks after the operation, William Mellor died.

In 1943 she made her first speech at the national conference of the Labour Party. This included an attack on the leadership of the party for not doing enough to force the government to implement the Beveridge Report. In July 1944 she married the journalist, Ted Castle.

Babara Castle worked as housing correspondent of the Daily Mirror during the Second World War and in the 1945 General Election she was elected to represent Blackburn in the House of Commons. Soon afterwards Stafford Cripps, the Minister of Trade, appointed Castle as one of his aides. Over the next few years she was associated with the left-wing of the party led by Aneurin Bevan.

Castle was Chairperson of the Labour Party (1958-59) and after the party won the 1964 General Election the new prime minister, Harold Wilson, appointed her as Minister of Overseas Development (1964-65) and Minister of Transport (1965-68). In this post she introduced the 70 mph speed limit, breathalyzer tests for suspected drunken drivers and compulsory seat belts. Wilson pointed out in his autobiography: Memoirs: 1916-1964 (1986): "Barbara proved an excellent minister. She was good at whatever she touched. I doubt if any member of the Cabinet worked longer hours or gave more productive thought to what they were doing."

In 1968 Castle became Secretary of State for Employment and Productivity (1968-70) and attempted to introduce the government's controversial prices and incomes policy. The publication of the white paper, In Place of Strife (1969) brought her into conflict with the trade unions and the left-wing of the Labour Party. Her critics were particularly hostile to the proposal for compulsory strike ballots. As Anne Perkins has pointed out: "Barbara's stock crashed to earth. But the ramifications went far beyond personal disaster. The episode accelerated a renewed alienation between party activists and the Labour leadership."

Castle lost office when the Conservative Party won the 1970 General Election. When the Labour Party returned to power in 1974 she became Secretary of State for Social Services (1974-76). In this post she introduced child benefit and established the link between pensions and earnings. She also attempted to bring an end to pay beds in the NHS. This led to doctors taking industrial action which closed accident and emergency wards in hospitals. When Jim Callaghan replaced Harold Wilson as prime minister he sacked Castle by claiming she was too old too serve in the cabinet.

Castle was a member of the European Parliament (1979-89) where she served as vice-chairperson of the Socialist Group (1979-86) and in 1990 joined the House of Lords. Over the next few years she successfully campaigned to restore the link between pensions and earnings. As The Times pointed out: "Lady Castle of Blackburn, a passionate socialist of the old school, kept up her scrutiny of government well into her eighties. At the 1999 Labour Party conference she savaged ministers for tying pensions to inflation, a move that led to the infamous 75p increase."

Castle published her political diaries and an autobiography, Fighting All the Way (1993). Barbara Castle died at her home in Buckinghamshire on 3rd May 2002.

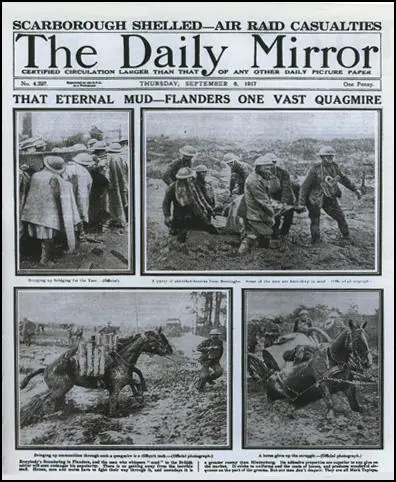

On this day in 1917 Canadian troops capture the village of Passchendaele in the Third Battle of Ypres. Three more attacks took place in October and on the 6th November the village of Passchendaele was finally taken by British and Canadian infantry. Sir Douglas Haig was severely criticized for continuing with the attacks long after the operation had lost any real strategic value. Since the beginning of the offensive, British troops had advanced five miles at a cost of at least 250,000 casualties, though some authorities say 300,000. "Certainly 100,000 of them occurred after Haig's insistence on continuing the fighting into October. German losses over the whole of the Western Front for the same period were about 175,000."

A copy of this newspaper can be obtained from Historic Newspapers.

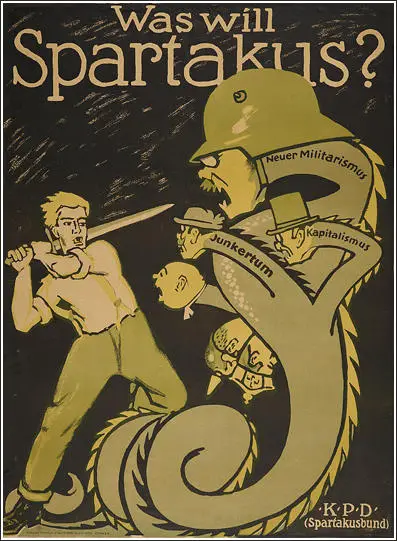

On this day in 1918, Karl Liebknecht, who was still in prison for his anti-war activities, demanded an end to the monarchy and the setting up of Soviets in Germany. Other members of the Spartacus League such as Rosa Luxemburg, Paul Levi and Leo Jogiches all recognised that a "successful revolution depended on more than temporary support for certain slogans by a disorganised mass of workers and soldiers". By 13th January, 1919 the rebellion had been crushed and most of its leaders were arrested. This included Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, who refused to flee the city, and were captured on 16th January and taken to the Freikorps headquarters. "After questioning, Liebknecht was taken from the building, knocked half conscious with a rifle butt and then driven to the Tiergarten where he was killed. Rosa was taken out shortly afterwards, her skull smashed in and then she too was driven off, shot through the head and thrown into the canal."

On this day in 1928 Josip Broz sentenced to 5 years in jail. On his release he went to live in the Soviet Union and in 1934 began working for the Comintern. Soon afterwards he obtained the nickname Tito. On the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War the Comintern established the Dimitrov Battalion. Named after Georgi Dimitrov the battalion comprised of Greeks and people from the Balkans. Tito eventually became one of the battalion's senior commanders.

On this day in 1944 Karl Hulten and Elizabeth Jones, killed a taxi driver in London. Three days earlier, Hulten, a member of the United States Army met Jones, an eighteen-year-old Welsh striptease dancer. On their first date they ended up using Hulten's truck to knock a young girl from her bike and stealing her handbag. The following day they gave a lift to a woman carrying two heavy suitcases. After stopping the car Hulten attacked the woman with an iron bar and then dumped her body in a river. On 6th October the couple hailed a hire car on Hammersmith Broadway. When they reached a deserted stretch of road they asked the taxi driver to stop. Hulten then shot the driver in the head and stole his money and car. The following day they spent the money at White City dog track. The couple were arrested on the 9th October. There was great public interest in the case of the GI gangster and his striptease dancer. The public was deeply shocked by the degree of violence the couple had used during their crime spree and it came as no surprise when both Karl Hulten and Elizabeth Jones were found guilty of murder and sentenced to death. Hulten was executed at Pentonville Prison on 8th March 1945 but Jones was reprieved at the last moment and was released in May 1954.

On this day in 1945 the writer Beatrice Kaufman died. Moss Hart entered the room five minutes later and found George Kaufman beating his head against the wall. He had always consulted Beatrice when he was writing plays. Arthur Kober said: "George valued her opinion probably more than anyone else." At the funeral he told his friend Russel Crouse, "I'm finished. Through. I'll never write again."

Beatrice Bakrow, the daughter of Julius Bakrow and Sarah Adler Bakrow, in Oxford Street, Rochester, on 20th January, 1895. According to her biographer, Michael Galchinsky: "She had two brothers, Leonard and Julian. Although few direct references to her Jewishness found their way into her later editorial work and writings, her early life fits the description of upper-middle-class German Jews who thought of themselves as liberal, modern, and forward-looking."

In 1913 Julius Bakrow sent her to Wellesley College but was expelled during her first year for staying out after hours. Her mother met her at the railway station and said: "Beatrice, you've been thrown out of Wellesley. What kind of man will you now?" In 1914 she entered University of Rochester but stayed only a year.

Beatrice Bakrow met the journalist, George S. Kaufman, in 1916, at the wedding of a mutual friend, Allan Friedlich. Howard Teichmann, the author of George S. Kaufman: An Intimate Portrait (1972), claimed that "Bea had developed into one of those large, unattractive girls who compensate for their lack of beauty by being bright, warm, ambitious, stylish, and charming. There was enough charm, enough style, enough ambition, enough warmth, and enough brightness within her to keep him at her side for the entire evening. Like her father, Bea had a full, slow, and rather lazy way of speaking. She did all the talking, and, characteristically, George listened - with interest."

The following day Beatrice and George drove by motor car to Niagara Falls. On her arrival home, Beatrice told her parents that she was going to marry Kaufman. Julius Bakrow objected to her choice when he discovered he was a journalist. "A vehement argument followed, but Bea stood firm and emerged victorious... Her friends in Rochester were astounded. Not only who was George Kaufman but who were his family, what were they, where did they come from, what business were they in, what did he do for a living, and, of course, the ultimate question: how did his future prospects look?"

Kaufman approached his friend, Franklin Pierce Adams, and told him: "Keep the middle of next March open, will you, Frank? I've found a kid upstate who's a peach." Adams, who had observed that the young journalist had never had a girlfriend before, asked: "Are you telling me you're getting married?" Kaufman replied: "Unless it's declared unconstitutional, I am." Adams agreed to be Kaufman's best man at the wedding.

Beatrice and George were married in high-style at the Rochester Country Club on 15th March, 1917. George was too busy with his work at his new post at the New York Times to take a honeymoon. Glancing at the newspapers as they boarded the train that took them back to New York City, George discovered that Tsar Nicholas II had been forced to abdicate. He commented to Beatrice: "Well, it took the Russian Revolution to keep us off the front page."

Beatrice later told a friend: "We were terribly innocent. We were both virgins, which shouldn't happen to anybody." She soon found herself pregnant but unfortunately the child was deformed and stillborn. As their friend, Howard Teichmann, has pointed out: "Beatrice was as crushed as any woman would be, but George's reaction was totally unexpected and heartbreaking to both of them. Following their misfortune, George found himself physically unable to have sexual intercourse with Bea.... There were embarrassed conversations followed by empty promises. First came twin beds, then separate bedrooms, and although George remained Bea's husband, he never again was her lover."

According to Dorothy Michaels Nathan, her friend from childhood, "Beatrice started seeing men even before George started with women." Another friend, the author Alexander King, saw it differently: "Beatrice was one of those great daring women who knows that her husband is having extramarital relations and knows that everybody else knows it, and knows that this can be borne either by throwing fits in lobbies or by being Wife Number One. And she was Wife Number One."

Brian Gallagher, the author of Anything Goes: The Jazz Age of Neysa McMein and her Extravagant Circle of Friends (1987), has argued: "Their lack of sexual experience must have contributed to George's inability to have intercourse with Bea after her miscarriage early in their marriage, and so helped start him on a twenty-year sexual binge... Bea, in the meanwhile, made her own, quite full sexual life, although something of its substitute character is seen in the fact that a majority of the men in it bore a distinct resemblance to George."

Beatrice was determined to establish her own career. At first she was a press agent for three sisters, Constance Talmadge, Norma Talmadge and Natalie Talmadge. Later she worked as a play reader for the Broadway producer, Morris Gest, and as an editor with the publisher, Horace Liveright. It is claimed that she played an important role in discovering and promoting the talent of Clifford Odets, Ernest Hemingway, John Steinbeck, William Faulkner, Djuna Barnes, Bennett Cerf, Oscar Levant, Moss Hart and William Saroyan.

In 1919 George S. Kaufman began taking lunch with a group of young writers in the dining room at the Algonquin Hotel. One of the members, Murdock Pemberton, later recalled that he owner of the hotel, Frank Case, did what he could to encourage this gathering: "From then on we met there nearly every day, sitting in the south-west corner of the room. If more than four or six came, tables could be slid along to take care of the newcomers. we sat in that corner for a good many months... Frank Case, always astute, moved us over to a round table in the middle of the room and supplied free hors d'oeuvre. That, I might add, was no means cement for the gathering at any time... The table grew mainly because we then had common interests. We were all of the theatre or allied trades." Case admitted that he moved them to a central spot at a round table in the Rose Room, so others could watch them enjoy each other's company.

This group eventually became known as the Algonquin Round Table. Other regulars at these lunches included Beatrice Kaufman, Robert E. Sherwood, Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, Alexander Woollcott, Heywood Broun, Harold Ross, Franklin Pierce Adams, Donald Ogden Stewart, Edna Ferber, Ruth Hale, Jane Grant, Neysa McMein, Alice Duer Miller, Charles MacArthur, Marc Connelly, Frank Crowninshield, John Peter Toohey, Lynn Fontanne, Alfred Lunt and Ina Claire.

In 1921 Beatrice Kaufman joined the Lucy Stone League. The first list of members included only fifty names. This included Ruth Hale, Heywood Broun, Jane Grant, Neysa McMein, Franklin Pierce Adams, Anita Loos, Zona Gale, Janet Flanner and Fannie Hurst. Its principles were forcefully expressed in a booklet written by Hale: "We are repeatedly asked why we resent taking one man's name instead of another's why, in other words, we object to taking a husband's name, when all we have anyhow is a father's name. Perhaps the shortest answer to that is that in the time since it was our father's name it has become our own that between birth and marriage a human being has grown up, with all the emotions, thoughts, activities, etc., of any new person. Sometimes it is helpful to reserve an image we have too long looked on, as a painter might turn his canvas to a mirror to catch, by a new alignment, faults he might have overlooked from growing used to them. What would any man answer if told that he should change his name when he married, because his original name was, after all, only his father's? Even aside from the fact that I am more truly described by the name of my father, whose flesh and blood I am, than I would be by that of my husband, who is merely a co-worker with me however loving in a certain social enterprise, am I myself not to be counted for anything."

It is claimed that Beatrice Kaufman was very promiscuous.Howard Teichmann tells the story of how she used to seduce young men: "At one of the larger parties that she and George gave so regularly, Beatrice spotted an attractive young man. There were several bedrooms in the Kaufman apartment, but none seemed appropriate. Stepping out, she and the young man went to the Plaza Hotel, where he signed the register. The room clerk looked over this unlikely couple with no baggage and a single intention." The clerk told the young man that there were no rooms available. When the young man told her this, Beatrice walked up to the desk and exclaimed: "See here, I am Mrs George S. Kaufman!" With this comment the clerk gave them a room.

In 1934 George S. Kaufman became involved in a national scandal. Franklin Thorpe, the husband of the actress Mary Astor, told the newspapers during a custody battle, that his wife's diary revealed that she had been having an affair with Kaufman. The story made the front page of the New York Times. At the time Beatrice was on holiday in London with Edna Ferber, Charles MacArthur, Helen Hayes, Irving Berlin, Margaret Leech and Raoul Fleishmann.

Leech recalled that "Beatrice was terribly upset and embarrassed. Newsman were standing around waiting for her, and she couldn't even go out to a restaurant without being mobbed by them." Fleishmann found her red-eyed from crying in her hotel room: "I'm so sorry. I'm so horribly upset that this should happen to George. I can't stand the thought of how badly he feels."

When they all arrived back in New York City there were at least forty reporters at the pier waiting for them. Beatrice went up to them and said: "I am not going to divorce Mr. Kaufman. Young actresses are an occupational hazard for any man working in the theatre." In the divorce court Mary Astor admitted that she had been having an affair with Kaufman. However, the diary was deemed as admissible and the judge ordered it be sealed and impounded.

In 1935 George S. Kaufman went to work in Hollywood. She wrote about the experience to her mother: "The party at the (Donald Ogden) Stewarts was great fun the other night and my evening was made for me when Mr. Chaplin sat down beside me and stayed for hours. Or did I write you that: I can't remember. He is very amusing and intelligent and I enjoyed talking to him a great deal. Paulette Goddard was there too - very beautiful; everyone says they are married. Joan Bennett, Clark Gable, the Fredric Marches, Dotty Parker, Mankiewiczes, etc. A delicious buffet dinner, with talk and bridge afterwards. Their house is lovely. Saturday night's party which Kay Francis gave was swell, too. She took over the entire Vendome restaurant and had it made over like a ship -a swell job. I seemed to know almost everyone there - there were over a hundred people. A sprinkling of movie stars - James Cagney, the Marches again, June Walker, etc. I arrived home at a quarter to five completely exhausted, having danced and drunk a good deal."

One of their closest friends, Ruth Goetz, later recalled: "They really lived high. Beatrice liked all the goodies of life. She was a great, robustious, fat, yummy woman, bouncy as hell. She loved people and drinking and eating. And she proposed to live that way. She was driven to work by her chauffeur, in her limousine, with a lap robe across her knees. She liked funny people and she liked fellows and she liked women. She was wonderfully hospitable and dear. She wanted a good time, and George was a man who never wanted a good time in his life. I think he had many good times, but they came to him by accident. She had to fill in many a long, dreary spell, which she did. She filled it with thousands of friends and a household that she ran extremely lavishly. Beatrice and George, in a curious way, they made it with that marriage, they really did. It was totally unsuited. The things she liked, he didn't. But he would have had no friends without her. She served her end of the marriage and he his. The marriage was on the surface, although one knew that the core was out of it and had been for many years. Still she really loved him. And so it worked. If one person goes on loving, it can be managed."

Edna Ferber thought that despite her many affairs, Beatrice was a good wife: "The wonderful Beatrice was the great influence in George's life. Sustaining, warm, perceptive, enormously companionable, she could go out to the corner to mail a letter and make the errand sound more adventurous and amusing than Don Quixote's journeyings." Another friend, Esther Adams, the wife of Franklin Pierce Adams, commented "Beatrice was like putting your hands in front of a warm stove. She was so appreciative and humorous.""

On this day in 1951 Joseph Stalin proclaims the Soviet Union has the atomic bomb.

On this day in 1960 Spartacus, screenplay by Dalton Trumbo, blacklisted because of McCarthyism premieres in New York City. Trumbo became the first blacklisted writer to use his own name when he wrote the screenplay for a Hollywood film. Based on the novel by another left-wing blacklisted writer, Howard Fast, it is a film that examines the spirit of revolt. Trumbo refers back to his experiences of the House of Un-American Activities Committee. At the end, when the Romans finally defeat the rebellion, the captured slaves refuse to identify Spartacus. As a result, all are crucified. Ironically, much of Spartacus was filmed on land owned by William Randolph Hearst. It was Hearst's newspapers that played such an important role in making McCarthyism possible.

On this day in 1973, Egyptian and Syrian forces launched a surprise attack on Israel. On 6th October 1973, Egyptian and Syrian forces launched a surprise attack on Israel. Two days later the Egyptian Army crossed the Suez Canal while Syrian troops entered the Golan Heights. Israeli troops counter-attacked on 8th October. They crossed the Suez Canal near Ismailia and advanced towards Cairo. The Israelis also recaptured the Golan Heights and moved towards the Syrian capital. The October War came to an end when the United Nations arranged a cease-fire on 24th October. The following year UN troops established a peace-keeping force on the Golan Heights. In September 1978, with the support of Jimmy Carter, the president of the United States, Menachem Begin of Israel and Anwar Sadat of Egypt signed a peace treaty between the two countries.