On this day on 1st June

On this day in 1563 Robert Cecil, the son of William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley and Mildred Cooke, was born on 1st June, 1563 at Cecil House, Strand, London. At the time his father was Secretary of State and the main advisor to Queen Elizabeth.

Mathew Lyons has pointed out that Cecil's closeness to Queen Elizabeth resulted in hostility of the nobility. "The group's Catholicism distracts from the more general reactionary nostalgia of its worldview... It was fed by resentment of the rising gentry families, of which Cecil was the most egregious and of course most powerful example; by a sense of sour entitlement, the humiliation of proud men excluded from positions of influence that their ancestors had held."

When he was a child Richard Cecil was dropped by his nursemaid and left with permanent curvature of the spine. (3) He was educated at home, first by his mother, one of the most learned women of her generation, then by tutors. He was taught Greek, Latin, French, Italian, and Spanish, together with music, mathematics, and cosmography. Cecil was thoroughly grounded in the Bible and the prayer book. His parents took care to converse over meals with Richard and the other children. This included Robert Devereux, the young son of Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex, who had died in 1576.

Anka Muhlstein has argued "The two youngsters, so dissimilar in their tastes and talents, had never been close, but William Cecil's affection for Essex and the later's respect for the old man were never disputed." Robert Lacey, the author of Robert, Earl of Essex (1971) has claimed that Robert's presence caused problems for Richard: "Though Essex was younger than Cecil he must even then have overtopped the stunted cripple - and he far outshone him in beauty. Erect and wiry with a handsome head of curly hair, the nine-year-old Robert Devereux charmed everyone he met."

In 1580 Richard Cecil was admitted to Gray's Inn, and received legal instruction while continuing to live at home. In July 1581 he was at Cambridge University but there is no evidence that he completed an academic year, and he did not take a degree. After further tutoring at home in 1582 by William Wilkinson, fellow of St John's College, Cecil spent the summer and autumn of 1583 in Paris.

In August 1584 Cecil was elected to the House of Commons, for the borough of Westminster; he represented it again in 1586. He was a loyal supporter of Queen Elizabeth and followed closely the policies of William Cecil and Sir Francis Walsingham. This included supporting the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots. However, as Walsingham had feared, Elizabeth proved reluctant to execute her rival. Christopher Morris, the author of The Tudors (1955) has argued that Elizabeth feared that Mary's execution might precipitate the rebellion or invasion which everybody feared. "To kill Mary was also foreign to Elizabeth's accustomed clemency and to her native fear of drastic action."

At this time, one contemporary described him as "a slight, crooked, hump-back young gentleman, dwarfish in stature, but with a face not irregular in feature, and thoughtful and subtle in expression, with reddish hair, a thin tawny beard and large, pathetic greenish-coloured eyes." It is claimed that the Queen called him "my elf" or "my pigmy". Cecil later admitted that if you treasure honour, honesty and peace of mind you should stay out of Tudor politics as it was "a great task to prove one's honesty, and yet not spoil one's fortune."

In February 1588 he was involved in negotiations with Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma, in Ostend in the hope of averting war with Spain. He sent detailed observations back to his father, particularly on the build-up of Parma's army for the intended invasion of England. However, the Spanish Armada left Lisbon on 29th May 1588. It numbered 130 ships carrying 29,453 men, of whom some 19,000 were soldiers (17,000 Spanish, 2,000 Portuguese). The plan was to sail to Dunkirk in France where the Armada would pick up another 16,000 Spanish soldiers.

In 1589 Richard Cecil married Elizabeth Brooke, the daughter of William Brooke, 10th Baron Cobham, and his second wife, Frances Newton. Elizabeth had served Queen Elizabeth and had been a maid of honour. William Cecil and Mildred Cecil were delighted with what appears to have been a "love match". They had two children William and Frances, but Elizabeth died eight years after they married during the birth of her third child.

Following the death of Sir Francis Walsingham in 1590, Richard became a more important figure in the government and was knighted in May 1591. Three months later, at the age of twenty-eight, he was elevated to the Privy Council. He was fully committed to the task and in his first year attended 112 meetings out of 164. Cecil was also appointed as high steward of Cambridge University. His father warned him not to question the Queen's judgement. It could be done, but most would be gained by allowing her to make up her own mind.

Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, saw the rise of Robert Cecil in the Privy Council as a threat to his own position. According to Richard Rex this illustrated the conflict between the "sword", the old concept of the nobility as based in military service to the Crown, and the "pen", the new concept of service in administration. With his father suffering from poor health, Cecil became more and more important to the Queen. In February 1594, Cecil was described as coming and going constantly to the court "with his hands full of papers and head full of matter", so preoccupied that he "passeth through the chamber like a blind man not looking upon any".

William Cecil, Lord Burghley, was still the Queen's principal councillor but he was growing old. Aware that she would soon need to replace Burghley, on 5th July 1596, she appointed Robert Cecil as her new Secretary of State. Essex was furious as he now realised that he "was no longer her pre-eminent favourite, but just one among her councillors".

Lord Burghley became seriously ill and seemed to be near death. Queen Elizabeth prayed for him daily and frequently visited him. "When the patient's food was brought and she saw that his gouty hands could not lift the spoon, she fed him. (20) Lord Burghley, the only man that Queen Elizabeth probably loved, died at his Westminster house on 4th August 1598. Elizabeth was deeply affected, retiring to her home to weep alone. (21) It is claimed that for the next few months the Privy Council did their best not to mention him at meetings when the Queen was present because it always made her breakdown in tears.

In his father's will Cecil received Theobalds and the Hertfordshire estates, but the title, the great house Stamford Baron, and the other estates all went to his half-brother, Thomas Cecil, Burghley's son from his first marriage. Some of his enemies believed that without the support of his father, his political career would go into decline. It was expected that Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, would now become the most significant figure in Queen Elizabeth's government.

However, as Lacey Baldwin Smith, the author of Treason in Tudor England (2006) has pointed out "no matter when Cecil entered the revolving door of Elizabethan politics, he invariably contrived to exit in front of Essex, and to do so while the Earl was safely away from court attempting to win military laurels." (24) Cecil "preferred to pursue a more defensive strategy, with the aim of keeping Spain at arm's length" whereas Essex "represented noble and martial valour". It has been argued that for Essex war "was a form of sport or game; for Cecil it was a source of expense and danger."

Before this happened, Queen Elizabeth, sent Essex to Ireland to deal with Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone, who had destroyed an English army at the battle of the Yellow Ford on the Blackwater river. An estimated 900 men were killed including their commander, Henry Bagenal. It was the heaviest defeat the English forces had ever experienced in Ireland. The Queen agreed and gave him a far larger army and more supplies than had been allowed for any previous Irish expedition.

It has been argued that Queen Elizabeth selected the Earl of Essex for this task because he had demonstrated on several occasions his courage and powers of leadership. "More importantly, his popularity gave him an incalculable advantage over the other candidates... Men responded to his name with enthusiasm, and this disposed of the difficulty of raising a large force - an indispensable prerequisite of success. Everyone was eager to serve under Essex."

Elizabeth Jenkins, the author of Elizabeth the Great (1958) pointed out that it was not long before Essex realised he had made a serious political mistake: "But almost at once, and long before his forces were embarked, Essex was regarding his appointment with self-pitying bitterness. He had felt he owed it to himself to allow no one else to take it, but he foresaw that once he was over the Irish Sea, his enemies in Council would undermine him... He departed on a tide of popular enthusiasm, the crowd following him for four miles as he rode out of London, but from the outset he bore himself in an injured and almost hostile manner to the Queen and Council."

On 27th March, 1599, Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, set off with an army of 16,000 men. He originally intended to attack the Earl of Tyrone in the north, both by sea and by land. On his arrival in Dublin he decided he needed more ships and horses to do this. Information he received suggested he was significantly outnumbered. Essex also feared that Spain would send soldiers to support the 20,000 Irishmen in Tyrone's army.

Essex decided to launch an expedition against Munster and Limerick. Although this did not bring a great deal of success he knighted several of his officers. This upset the Queen as only she had the power to confer knighthoods. This lasted two months and upset Queen Elizabeth who demanded that Essex confronted Tyrone's army. She pointed out that such a large army was costing her £1,000 a day.

Essex insisted he could not do this until more men from England arrived. He also began to worry that his enemies were keeping him short of supplies on purpose: "I am not ignorant what are the disadvantages of absence - the opportunities of practising enemies when they are neither encountered nor overlooked." As a result of military action and especially illness, Essex now only had 4,000 fit men.

Essex reluctantly marched his men north. The two armies faced each other at a ford on the River Lagan. Essex, aware he was in danger of experiencing an heavy defeat, agreed to secret negotiations. The two men announced a truce but it was not known at the what was said during these talks. Essex's enemies back in London began spreading rumours that he was guilty of treachery. It later emerged that Essex had offered without permission, Home Rule for Ireland.

Queen Elizabeth reacted to this news by appointing Robert Cecil to become master of the Court of Wards, a lucrative post that Essex himself had hoped to occupy. Essex wrote to the Queen that "from England I have received nothing but discomfort and soul's wounds" and that "Your Majesty's favour is diverted from me and that already you do bode ill both to me and to it?" According to Pauline Croft this new post "controlled a great array of patronage both at court and in the counties". However, "by far the most significant aspect of his elevation was that it signalled unequivocally that the queen recognized his personal worth and ability".

Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, now lost all his power in government. On 7th February, 1601, he was visited by a delegation from the Privy Council and was accused of holding unlawful assemblies and fortifying his house. Fearing arrest and execution he placed the delegation under armed guard in his library and the following day set off with a group of two hundred well-armed friends and followers, entered the city. Essex urged the people of London to join with him against the forces that threatened the Queen and the country. This included Robert Cecil and Walter Raleigh. He claimed that his enemies were going to murder him and the "crown of England" was going to be sold to Spain.

Walter Raleigh attempted to negotiate with rebel kinsman Sir Ferdinando Gorges on boats in the middle of the Thames, "counselling common sense, discretion, and reliance on the queen's clemency". Gorges refused, honouring his commitment to Essex and warning Raleigh of bloody times ahead. While they talked, Essex's stepfather, Sir Christopher Blount aimed four bullets at Raleigh from Essex House, but the optimistic shots missed their target. Recognizing the futility of negotiation, Raleigh hurried to court and mobilized the guard.

At Ludgate Hill his band of men were met by a company of soldiers. As his followers scattered, several men were killed and Blount was seriously wounded. Essex and about 50 men managed to escape but when he tried to return to Essex House he found it surrounded by the Queen's soldiers. Essex surrendered and was imprisoned in the Tower of London.

On 19th February, 1601, Essex and some of his men were tried at Westminster Hall. He was accused of plotting to deprive the Queen of her crown and life as well as inciting Londoners to rebel. Essex protested that "he never wished harm to his sovereign". The coup, he claimed was merely intended to secure access for Essex to the Queen". He believed that if he was able to gain an audience with Elizabeth, and she heard his grievances, he would be restored to her favour.

During the trial, Essex accused Robert Cecil of favouring the right to the English throne of Archduchess Isabella, daughter of Philip II and co-regent with her husband Albert VII. Cecil dramatically interrupted, stepping out from behind a tapestry to beg permission to defend himself from the wild charge. He demanded that Essex reveal his source for the statement. Essex replied that his uncle Sir William Knollys had told him so. However, when Knollys was brought in, he cleared Cecil completely. Cecil, turning to Essex, told him that his malice proceeded from his passion for war, in contrast to Cecil's own desire for peace in the best interests of the country. He continued, "I stand for loyalty, which I never lost: you stand for treachery, wherewith your heart is possessed". Essex was found guilty of treason and sentenced to death.

In the early hours of 25th February, Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, attended by three priests, sixteen guards and the Lieutenant of the Tower, walked to his execution. In deference to his rank, the punishment was changed to being beheaded in private, on Tower Hill. Essex was wearing doublet and breeches of black satin, covered by a black velvet gown; he also wore a black felt hat. As he knelt before the scaffold Essex made a long and emotional speech of confession where he admitted that he was "the greatest, the most vilest, and most unthankful traitor that ever has been in the land". His sins were "more in number than the hairs" of his head. It took three strokes of the axe to sever his head.

Queen Elizabeth was now sixty-years old: "Her nose had slightly thickened, her eyes became sunken, and as she had lost several teeth on the left side of her mouth it was difficult for foreigners to catch her words when she spoke fast, but the impression she made in her last decade was one of astonishing energy for her years. She was erect and active as ever and though her face was wrinkled her skin preserved its flawless white."

Elizabeth, who had difficulty sleeping, often worked before delight with her officials. All measures relating to public affairs were read over to her and she made notes on them, either in her own hand or dictating her comments to secretaries. Robert Cecil discovered he had to be very careful with the way he treated the Queen. During one long meeting with her one evening he noticed she looked tired and suggested that she "must" go to bed. The Queen replied, "Little man, little man, the word must is not to be used to Princes."

Queen Elizabeth, was 67 years-old on 7th September, 1600. When she was younger she enjoyed riding, walking and dancing. However, for the past few years her frequent illnesses had pulled her down alarmingly. Ambassadors reported that she had suffered from fever, gastric attacks and neuralgia. She was described as "very thin", "the colour of a corpse" and that "her bones could be counted". At the opening of Parliament her robes of velvet and ermine were found to be too heavy for her and on the steps of the throne she staggered and was only saved from falling by the peer who stood next to her.

Robert Cecil made strenuous attempts to sort out the Queen's finances that had been badly damaged by recent military adventures. Cecil advocated a foreign policy of peaceful co-existence with other major powers in Europe. When she ascended the throne the ordinary revenue amounted to some £200,000 a year, to which parliamentary subsidies added £50,000. By 1600 ordinary revenue had increased to £300,000, and parliamentary subsidies were now worth £135,000. Yet during this period the Queen's expenditure had gone up far more than her income. This was partly due to inflation. Between 1560 and 1600 prices had risen by at least 75%.

Queen Elizabeth had to constantly appeal to Parliament to grant her more money. However, by 1601 members began to express doubts about whether the country could actually bear so heavy a burden of taxation. They also complained bitterly about Elizabeth's policy of granting of monopolies. These were patents granted to individuals which allowed them to manufacture or distribute certain named articles for their private profit. It was a device by which Elizabeth could confer benefits on favoured courtiers without putting her to any personal expense.

In the 1601 Parliament one member called monopolists "bloodsuckers of the commonwealth" and argued that they brought "the general profit into a private hand". In the last few years the Queen had granted at least thirty new patents on items that included currants, iron, bottles, vinegar, brushes, pots, salt, lead and oil. Francis Bacon suggested that Parliament petition the Queen over this issue but some members wanted to take more direct action. Robert Cecil said he had never seen Parliament like this before: "This is more fit for a grammar school than a court of Parliament". As a result of these complaints proclamations were therefore issued cancelling the principal monopolies. In return, Parliament agreed to impose taxes in order to increase the Queen's income.

Robert Cecil believed that James VI of Scotland was by far the strongest claimant to the English throne, but Elizabeth could not be brought to acknowledge him openly as her heir. In May 1601 Cecil took the decision to begin secret negotiations with James. "The secret correspondence between them was legally treasonable, but Cecil sensed that such a link was the only practical way to ensure in advance that the transition of power, whenever it came, would be peaceful."

Cecil's covert correspondence was in code. Cecil was "10", Elizabeth "24" and James "30". Although he knew the Queen would disapprove of these negotiations he later justified his actions by arguing that "even with strictest loyalty and soundest reason for faithful ministers to conceal sometimes both thoughts and actions from princes when they are persuaded it is for their greater service". He added "if her Majesty had known all I did... her age... joined to the jealously of her sex, might have moved her to think ill of that which helped to preserve her."

Queen Elizabeth's final illness began late in 1602 and thereafter her decline was steady. Robert Cecil wrote to George Nicholson, the Queen's agent in Edinburgh, that Elizabeth "hath good appetite, and neither cough nor fever, yet she is troubled with a heat in her breasts and dryness in her mouth and tongue, which keeps her from sleep, greatly to her disquiet."

Unable to eat much and unwilling to sleep, her last days were difficult. Aware that she was dying Cecil attempted to persuade her to nominate a successor. Believing her unable to speak, they offered to run through a list of candidates and asked her to lift a finger if she wished to approve one. Various names left her unmoved. However, when she got to the name of Edward Seymour, Viscount Beauchamp, she burst into life: "I will have no rascal's son in my seat, but one worthy to be a king."

Soon afterwards an abscess burst in her throat and she recovered a little and was able to sip some broth. Then she declined again and knowing the end was coming, Cecil asked her if she accepted James VI of Scotland as her successor. She had lost the power of speech and merely made a gesture towards her head which they interpreted as one of consent.

Comte de Beaumont, the French ambassador, wrote to King Henry IV on 14th March, that the Queen did not speak for three days. When she regained consciousness she said, "I wish not to live any longer, but desire to die." He added that "she is moreover said to be no longer in her right senses: this, however, is a mistake; she has only had some slight wanderings at intervals."

Four days later Beaumont reported: "The Queen is already quite exhausted, and sometimes, for two or three days together, does not speak a word. For the last two days she has her finger almost always in her mouth, and sits upon cushions, without rising or lying down, her eyes open and fixed on the ground. Her long wakefulness and want of food have exhausted her already weak and emaciated frame, and have produced heat in the stomach, and also the drying up of all the juices, for the last ten or twelve days."

On 24th March, 1603, Archbishop John Whitgift was instructed to visit Queen Elizabeth. The seventy-three year old head of the church knelt by her bed and prayed. After about 30 minutes he attempted to get up but she made a sign that suggested he carried on praying. He did so for another half-hour and when he attempted to rise, the Queen gestured with her hand to keep on the floor. Eventually, she sank into unconsciousness and he was allowed to leave the room. She died later that day.

It was Robert Cecil who read out the proclamation announcing James as the next king of England on the day Elizabeth died, first at Whitehall, then in front of St Paul's Cathedral and a third time at Cheapside Cross. James wrote from Edinburgh informally confirming all the privy council in their positions, adding in his own hand to Cecil, "How happy I think myself by the conquest of so wise a councillor I reserve it to be expressed out of my own mouth unto you".

Cecil remained in London for a short time, to ascertain that there was no outbreak of trouble in the capital or elsewhere over the change of dynasty, and also to make arrangements for Elizabeth's funeral. On Thursday 28th April, a procession of more than a thousand people made its way from Whitehall to Westminster Abbey. "Led by bell-ringers and knight marshals, who cleared the way with their gold staves, the funeral cortege stretched for miles. First came 260 poor women... Then came the lower ranking servants of the royal household and the servants of the nobles and courtiers. Two of the Queen's horses, riderless and covered in black cloth, led the bearers of the hereditary standards... The focal point of the procession was the royal chariot carrying the Queen's hearse, draped in purple velvet and pulled by four horses... On top of the coffin was the life-size effigy of Elizabeth... Sir Walter Raleigh and the Royal Guard walking five abreast, brought up the rear, their halberds held downwards as a sign of sorrow."

James VI told Thomas Cecil, 1st Earl of Exeter, that he had full confidence in his half-brother. "He said", reported Thomas, "he heard you were but a little man, but he would shortly load your shoulders with business". Robert Cecil was appointed as the king's Secretary of State. Cecil argued in a letter that he should be given "liberty to negotiate… at home and abroad with friends and enemies in all matters of speech and intelligence". Above all he insisted on the need for complete trust on both sides. "The prince's assurance must be his confidence in the secretary and the secretary's life his trust in the prince… the place of a secretary is dreadful if he serve not a constant prince".

When he opened his first Parliament in March 1604 James reminded members that he was the descendant of the royal houses of both York and Lancaster. "But the union of these two princely houses is nothing comparable to the union of two ancient and famous kingdoms, which is the other inward peace annexed to my person." One member of Parliament, Sir Christopher Pigott, made it quite clear that he was opposed to a union of the two countries. He told the House of Commons the Scots were "beggars, rebels and traitors" who had murdered all the kings. James was furious and ordered him to be sent to the Tower of London.

In November 1604 James VI wrote to Cecil complaining that English officials did not welcome the Scots, for they feared loss of office for themselves. He decided against giving Scotsmen senior posts in his administration. However, he did plan to reward his followers and a total of 158 Scotsman were given positions in his government and household.

Robert Cecil led the successful negotiations with the envoys of Philip III of Spain. The peace brought great benefits to English trade, despite occasional objections from English merchants trading to Spain, who found conditions there much harder than they expected. It enhanced the prosperity of both London and the other ports in England. The 1604 treaty allowed Englishmen to trade and settle in the West Indies and North America. Cecil was rewarded by being given the title of Viscount Cranborne. The following year he became the Earl of Salisbury.

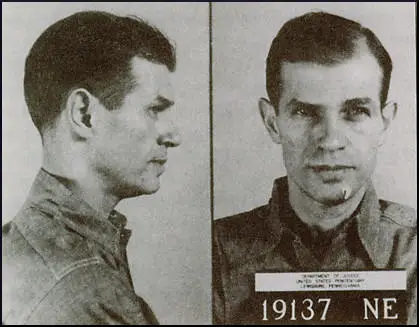

In 1605 Robert Catesby devised the Gunpowder Plot, a scheme to kill James and as many Members of Parliament as possible. At a meeting at the Duck and Drake Inn, Catesby explained his plan to Guy Fawkes, Thomas Percy, John Wright and Thomas Wintour. All the men agreed under oath to join the conspiracy. Over the next few months Francis Tresham, Everard Digby, Robert Wintour, Thomas Bates and Christopher Wright also agreed to take part in the overthrow of the king.

Catesby's plan involved blowing up the Houses of Parliament on 5th November. This date was chosen because the king was due to open Parliament on that day. At first the group tried to tunnel under Parliament. This plan changed when Thomas Percy was able to hire a cellar under the House of Lords. The plotters then filled the cellar with barrels of gunpowder. The conspirators also hoped to kidnap the king's daughter, Elizabeth. In time, Catesby was going to arrange Elizabeth's marriage to a Catholic nobleman.

One of the people involved in the plot was Francis Tresham. He was worried that the explosion would kill his friend and brother-in-law, Lord Monteagle. On 26th October, Tresham sent Lord Monteagle a letter warning him not to attend Parliament on 5th November. Monteagle became suspicious and passed the letter to Robert Cecil. Cecil quickly organised a thorough search of the Houses of Parliament. While searching the cellars below the House of Lords they found Guy Fawkes and the gunpowder. Fawkes claimed he was John Johnson, the servant of Thomas Percy.

Guy Fawkes was tortured and admitted that he was part of a plot to "blow the Scotsman (James) back to Scotland". On the 7th November, after enduring further tortures, Fawkes gave the names of his fellow conspirators. Fawkes, Everard Digby, Robert Wintour, Thomas Bates, and Thomas Wintour, were all hanged, drawn and quartered.

This is the traditional story of the Gunpowder Plot. However, in recent years some historians have begun to question this version of events. Some have argued that the plot was really devised by Cecil. This version claims that Cecil blackmailed Catesby into organising the plot. It is argued hat Cecil's aim was to make people in England hate Catholics. For example, people were so angry after they found out about the plot, that they agreed to Cecil's plans to pass a series of laws persecuting Catholics.

Cecil's biographer, Pauline Croft, has argued that this is unlikely to have been true: "In the inflamed atmosphere after November 1605, with wild accusations and counter-accusations being traded by religious polemicists, there were allegations that Cecil himself had devised the Gunpowder Plot to elevate his own importance in the eyes of the king, and to facilitate a further attack on the Jesuits. Numerous subsequent efforts to substantiate these conspiracy theories have all failed abysmally."

Robert Cecil definitely took advantage of the situation. Henry Garnett, head of the Jesuit mission in England, was arrested. As Roger Lockyer has pointed out: "The evidence against him was largely circumstantial, but the government was determined to tar all the missionary priests with the brush of sedition in the hope of thereby depriving them of the support of the lay catholic community. A further step in this direction came in 1606, with the drawing up of an oath of allegiance which all catholics were required to take."

James VI was a regular visitor to Salisbury's magnificent home, Theobalds. The king loved hunting in the great park and in May 1607 Salisbury agreed to exchange the estate for a grant of other royal properties, most importantly the old palace of Hatfield House. Cecil now spent over £38,000 on its redevelopment. "Salisbury... set out to build a new mansion that was far different in style from the sprawling palace that Lord Burghley had erected. Compact, comfortable, and sumptuously decorated, Hatfield House marked a new departure in English domestic architecture."

Robert Cecil, Earl of Salisbury, took over the Treasury in 1608. He discovered that the King was well over a million pounds in debt and running an annual deficit approaching £100,000. In an effort to solve the problem he increased the number of Impositions (duties on selected imports and exports which were levied by virtue of the royal prerogative and without any parliamentary sanction). As a result of his efforts the debt was substantially reduced, but he could not eliminate it altogether.

Salisbury proposed that Parliament should vote the King a sum of £600,000, so that the debt should be eliminated and a reserve fund established. In return the King would surrender a number of its feudal prerogatives and the reform of the Court of Wards. After several months of haggling the House of Commons agreed that if the Court of Wards was abolished it would provide £200,000 a year. However, when the members consulted their constituents and found that there was widespread opposition to the plan.

It has been argued that Salisbury "bore the brunt of the growing dislike of the Court's financial privileges and the patronage system - and indeed, he was as responsible as anyone for turning the Tudor method of getting things done into the vicious Stuart machine of bribery".

James blamed Salisbury for this failure: "Your greatest error hath been that ye ever expected to draw honey out of gall, being a little blinded with the self-love of your counsel in holding together of this Parliament." Salisbury responded to James by making it clear that he had little more to offer: "I be not able to recover your estate out of the hands of those great wants to which your parliament hath now abandoned you".

Despite these harsh words James showed his appreciation of Salisbury's tireless efforts on his behalf by renewing, for a further nineteen years, the extremely lucrative silk farm concession originally granted in 1601. It is estimated that this concession was worth about £7,000 per annum.

In February 1612, Robert Cecil, Earl of Salisbury, was taken very ill suffering from severe stomach pains. He went to Bath, his condition being made worse by the rattling of the coach on a five days' journey. He then decided to return to London but he failed to arrive, dying of stomach cancer at Marlborough, Wiltshire, on 24th May 1612.

On this day in 1801 Brigham Young was born in Whittingham, Vermont. He worked as a carpenter and joiner in Mendon, New York. In 1830 Young read the Book of Mormon. Two years later Young joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and was sent to preach in Canada.

In 1834 Young accompanied Joseph Smith in the Mormon march to Missouri. The following year he was named third of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. In 1839 Young travelled to England where he established a mission that eventually was responsible for persuading large numbers to emigrate to the United States.

Young returned to the Mormon community of Nanvoo in Commerce, Illinois. By 1843 the Mormons had over 20,000 members. Mormon views on plural marriage created a great deal of local hostility and Joseph Smith and his brother, Hyrum Smith, were imprisoned. On 27th June, 1844, 150 masked men broke into Carthage jail and killed the two men.

After the death of Joseph Smith Young emerged as the new leader of the Mormons. Driven out of Illinois, Young led the expedition to the Rocky Mountains. He selected Salt Lake in Utah as the main gathering place of the Mormons and in December, 1847 became president of the church.

In 1850 President Millard Fillmore appojnted Young as governor of Utah. He held the position until 1857 when President James Buchanan sent in federal troops led by General Albert S. Johnson to remove him from power. Although denied political office, Young remained president of the Mormon church.

Unlike some religions like the Quakers, the Mormons supported the idea of owning slaves. Young told Horace Greeley in 1859: "We consider it of divine institution and not to be abolished... If slaves are brought here by those who owned them in the states, we do not favor their escape from the service of those owners."

Brigham Young argued in 1870: "Since the day that we first trod the soil of these valleys, have we received any assistance from our neighbors? No, we have not. We have built our homes, our cities, have made our farms, have dug our canals and water ditches, have subdued this barren country, have fed the stranger, have clothed the naked, have immigrated the poor from foreign lands, have placed them in a condition to make all comfortable and have made some rich. We have fed the Indians to the amount of thousands of dollars yearly, have clothed them in part, and have sustained several Indian wars, and now we have built thirty-seven miles of railroad."

In 1871 Brigham Young was arrested for bigamy. A supporter of the doctrine of plural marriage, during his lifetime Young had over fifty wives and had 59 children by 16 of his wives. However, he admitted: "some of those sealed to me are old ladies whom I regard rather as mothers than wives, but whom I have taken home to cherish and support."

Brigham Young died in Salt Lake City on 29th August, 1877. By this time he had acquired a considerable fortune and left over $2,500,000 to his wives and children.

On this day in 1915 Harold Chapin, letter to Alice Chapin about life in the trenches.

Things have quieted down now - only aeroplanes and anti-aircraft guns with occasional, very occasional, five minutes of shelling disturb the town. After the inferno which raged "out there" for the last two weeks the result of which you have seen by the papers, (it looks little enough but has cost both sides the most enormous efforts and really signifies much), the comparative calm is almost uncanny. Men of this or that battalion are wandering aimlessly about the streets, getting arrears of food into them, and losing slowly the strained and distrait manner that their experiences have engendered...

These things almost please one by their very perfection of eeriness and horror. Do you understand? They are like the works of some gigantic supernatural artist in the grotesque and horrible. I shall never fear the picturesque in stage grouping again. Never have I seen such perfect grouping as when, after a shell had fallen round the comer from here a fortnight ago, three of us rushed round and the light of an electric torch lit up a little interior ten feet square, with one man sitting against the far wall, another lying across his feet and a dog prone in the foreground, all dead and covered evenly with the dust of powdered plaster and masonry brought down by the explosion! They might have been grouped so for forty years - not a particle of dust hung in the air, the white light showed them, pale whitey brown, like a terracotta group. That they were dead seemed right and proper - but that they had ever been alive - beyond all credence.

On this day in 1916 Louis Brandeis becomes the first Jew appointed to the United States Supreme Court. Louis Brandeis, the son of Jewish parents, was born in Louisville, Kentucky in 13th November, 1856. He was educated in Louisville and Dresden in Germany before graduating from Harvard University in 1877.

Brandeis worked as a lawyer in Boston where he showed a strong sympathy for the trade union movement and women's rights. This included him working without fees to fight for causes he believed in such as the minimum wage and anti-trust legislation.

Brandeis advised President Woodrow Wilson on policy and influenced his New Freedom economic doctrine. Brandies also published two important books during this period, Other People's Money (1914) and Business - A Profession (1914).

A supporter of trade union rights, Brandeis argued in these two books that the retailer should make sure that "the goods which he sold were manufactured under conditions which were fair to the workers - fair as to wages, hours of work, and sanitary conditions." He went on to claim that if the business community considered moral issues when producing and selling goods then 'big business' will then mean "business big not in bulk or power but great in service and grand in manner. Big business will then mean professionalized business, as distinguished from the occupation of petty trafficking or more moneymaking."

In 1916 Brandeis was appointed to the Supreme Court and this decision was attacked by business interests and anti-Semites. One of the justices, James McReynolds, hostility towards Jews was so strong he always refused to sit next to Brandeis during meetings. Over the next few years Brandeis was a strong advocate of individual rights and freedom of speech. This included his opposition to the Espionage Act passed during the First World War.

Louis Brandeis was often aligned with his friend, Oliver Wendell Holmes, in his decisions on the Supreme Court. Brandies favoured government intervention to control the economy and therefore defended most of the New Deal legislation that was introduced by Franklin D. Roosevelt during his period as president. However, Brandeis did argue that the National Recovery Administration (NRA) was unconstitutional.

Brandeis was a supporter of equality. He once said: "We can have democracy in this country, or we can have great wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can't have both." To those who argued that achieving equality of impossible, he replied: "Most of the things worth doing in the world had been declared impossible before they were done."

Louis Brandeis, who retired in February, 1939, died in Washington on 5th October, 1941. I. F. Stone wrote in the PM newspaper. He argued that the "Attorney for the People" derived his strength from his "vast appetite for the concrete details of any situation or problem, and his intellectual patience... Brandeis believed in the reasonableness of human beings and the possibilities of reaching them by persuasion."

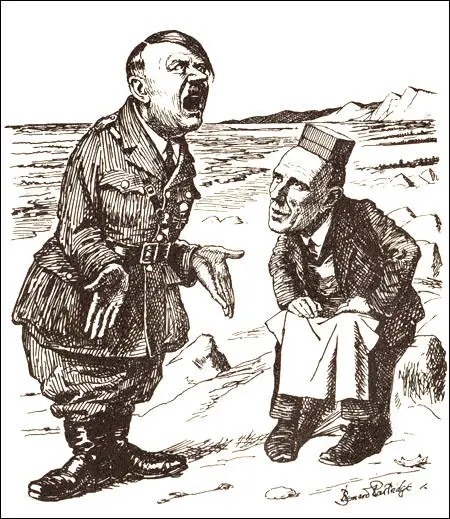

On this day in 1937 Nevile Henderson attended a banquet arranged by the German-English Society of Berlin. A large number of leading Nazis were in attendance when he made a speech where he defended Adolf Hitler and urged the British people to "lay less stress on Nazi dictatorship and much more emphasis on the great social experiment which is being tried out in this country."

This speech provoked an uproar and some left-wing journalists described him as "our Nazi ambassador at Berlin". However, some newspaper editors, including Geoffrey Dawson, the editor of The Times, supported this approach to Nazi Germany. In the House of Commons the Conservative Party MP, Alfred Knox offered congratulations "to HM Ambassador in Berlin on having made a real contribution to the cause of peace". Richard Griffiths, the author of Fellow Travellers of the Right (1979), has pointed out that "Henderson was not just an eccentric individual, as has been suggested; he stands as an example of a whole trend in British thought at the time."

Some senior figures at MI5 were very opposed to appeasement and supplied Neville Chamberlain with a document from a spy close to Hitler quoting him as saying: "If I were Chamberlain I would not delay for a minute to prepare my country in the most drastic way for a total war... It is astounding how easy the democracies make it for us to reach our goal....If the information which has proved generally reliable and accurate in the past is to be believed, Germany is at the beginning of a Napoleonic era and her rulers contemplate a great expansion of German power."

On this day in 1940 Philip Zec produces a cartoon on Dunkirk. A group of fifteen British and nine American journalists were allowed to travel with British troops to Europe. They were looked after by a group of Old Etonian, military officers, who were often drunk. This included the large landowner, Charles Tremayne, who was known to drink neat gin for breakfast and consumed three bottles of it every day. O. D. Gallagher, who worked for The Daily Mail later told Phillip Knightley: "The conducting officers were such astounding caricatures of British army regular officers and upper classes as to be scarcely credible. They were either drunk half the time or half drunk all the time."

Just over 338,200 troops (of whom 150,200 were French) were brought out through Dunkirk, mainly between 26th May and 4th June, and crossed the Channel to Britain in naval ships and in a flotilla of small craft assembled for the occasion. The total casualties of the British Army in France was 68,111. In all, 338,226 men were brought to England from Dunkirk, of whom 139,097 were members of the French Army. Left behind in France were 2,472 guns, 20,000 motorcycles, and almost 65,000 other vehicles. Almost all of the 445 British tanks that had been sent to France with the BEF were abandoned. Six destroyers had been sunk and nineteen damaged. The RAF had also lost 474 aircraft.

General William Ironside, chief of the Imperial General Staff, told Anthony Eden, "This is the end of the British Empire." Churchill appealed to the newspapers not to present it as a major defeat. The Daily Mirror described the operation as "Bloody Marvellous" and the Sunday Dispatch suggested that divine intervention had been responsible. It pointed out that Dunkirk had followed a nation-wide service of prayer and that during the evacuation "the English Channel, that notoriously rough stretch of water which has brought distress to so many holiday-makers in happier times, became as calm and smooth as a pond... and while the smooth sea was aiding our ships, a fog was shielding our troops from devastating attack by the enemy's air strength."

The New York Times went along with this message: "So long as the English tongue survives, the word Dunkirk will be spoken with reverence. For in that harbour, in such a hell as never blazed on earth before, at the end of a last battle, the rags and blemishes that have hidden the soul of democracy fell away. There, beaten but unconquered, in shining splendor, she faced the enemy."

Edward Murrow, of CBS, the radio station, was the only dissenting voice when he claimed that "there is a tendency to call the withdrawal a victory." However, this was something only available to an American audience. Phillip Knightley, the author of The First Casualty: The War Correspondent as Hero, Propagandist and Myth Maker (1982), has pointed out that "it was not until the late 1950s and early 1960's - nearly twenty years after the event - that a fuller, truer picture of Dunkirk began to emerge."

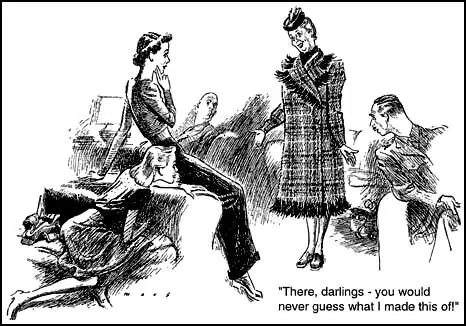

On this day in 1941 the British government introduces plans to ration clothes. A points system allowed people to buy one completely new outfit a year. To save fabric, men's trousers were made without turnups, while women's skirts were short and straight. Frills on women's underwear were banned.

Women's magazines were packed with handy hints on how, for example, old curtains might be cut up to make a dress. Stockings were in short supply so girls coloured their legs with gravy browning. Sometimes a friend would draw a line down the back of their legs with an eyebrow pencil for a seam.

In May 1943, the annual clothing coupon allowance was cut from 48 to 36 per adult. Later this number of coupons was cut to 20. When one considers that a coat needed 18 coupons this reduction caused serious problems for people.

On this day in 1949 Alistair Cooke, writes about the trial of Alger Hiss. "The trial will be haunted at every turn by the great political issue that bedevils the conscience and well-being of every responsible citizen of a democratic country. Has a democrat the right to be a communist and to keep his job and a good opinion of society? Across the square in which Mr Hiss will be tried, the trial of 11 communist leaders goes on to try to establish for the first time a court test of whether a communist is ipso facto a man dedicated to overthrow by force the government of this country. In the public mind the two trials set up a riptide in the ocean of fear and distrust that washes across all American discussion of communism. It is the sense of this embroilment in a conflict of belief that is happening to lesser men now suspect in their fields of scholarship or government, and the degree of mystery that surrounds the personal relationship of two brilliant young men, that has made this trial fascinating to people uninterested in the legal issue and made it read so far like an unwritten novel by Arthur Koestler."

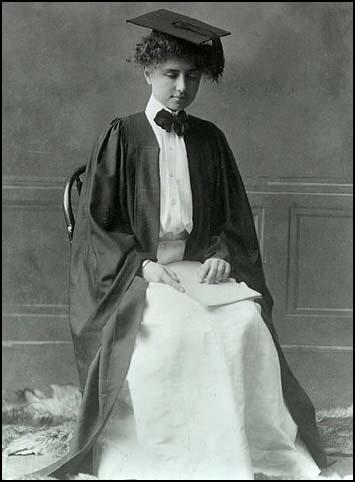

On this day in 1968 social activist Helen Keller died in Westport, Connecticut. Helen Keller was born in Tuscumbia, Alabama on 27th June, 1880. Her father, Arthur H. Keller, was the editor for the North Alabamian, and had fought in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War. At 19 months she suffered "an acute congestion of the stomach and brain (probably scarlet fever) which left her deaf and blind.

She later wrote in The Story of My Life: "In the dreary month of February, came the illness which closed my eyes and ears and plunged me into the unconsciousness of a new born baby. They called it acute congestion of the stomach and brain. The doctor thought I could not live. Early one morning, however, the fever left me as suddenly and mysteriously as it had come. There was great rejoicing in the family that morning, but no one not even the doctor, knew that I should never see or hear again." As a child she was taken to see Alexander G. Bell. He suggested that the family should contact the Perkins Institute for the Blind in Boston.

In 1886 the Perkins Institute provided Keller with the teacher Anne Sullivan. She later recalled: "We walked down the path to the well-house, attracted by the fragrance of the honeysuckle with which it was covered. Some one was drawing water and my teacher placed my hand under the spout. As the cool stream gushed over one hand she spelled into the other the word water, first slowly, then rapidly. I stood still, my whole attention fixed upon the motions of her fingers. Suddenly I felt a misty consciousness as of something forgotten - a thrill of returning thought; and somehow the mystery of language was revealed to me. I knew then that "w-a-t-e-r" meant the wonderful cool something that was flowing over my hand. That living word awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, joy, set it free! There were barriers still, it is true, but barriers that could in time be swept away." The 21 year old Sullivan worked out an alphabet by which she spelled out words on Helen's hand. Gradually Keller was able to connect words with objects.

Sullivan's teaching skills and Keller's abilities, enabled her at the age of 16 to pass the admissions examinations for Radcliffe College. While at college she wrote the first volume of her autobiography, The Story of My Life. It was published serially in the Ladies' Home Journal and, in 1902, as a book. By the time she had graduated in 1904 she had mastered five languages.

While at college she developed a strong interest in women's rights and became a militant campaigner in favour of universal suffrage. She also became friends with several notable public figures including John Greenleaf Whittier, Oliver Wendell Holmes and William Dean Howells. The journalist, Max Eastman, became a friend during this period. He later recalled: "The gleam of true, courageous and unaffected joy in living that shone out of her gray-blue eyes. Her face was round; she was a round-limbed girl, perpetually young in her bearing, as though her limitations had made it easy instead of hard to grow older."

Keller's political views were influenced by conversations she had with John Macy (Anne Sullivan's husband) and reading New Worlds for Old by H. G. Wells. In 1909 Keller became a socialist and was active in various campaigns including those in favour of birth control, trade unionism and against child labour and capital punishment.

Keller was a supporter of Emmeline Pankhurst and the militant Women's Social and Political Union in Britain. She told the New York Times: "I believe the women of England are doing right. Mrs Pankhurst is a great leader. The women of America should follow her example. They would get the ballot much faster if they did. They cannot hope to get anything unless they are willing to fight and suffer for it.

In 1912 Keller was interviewed by Ernest Gruening, a young journalist working for the Boston American. He later wrote about it in his autobiography, Many Battles (1973): "She had never before been interviewed for publication, so I communicated with her teacher-companion, Anne Sullivan Macy, and on securing assent went to their home in Wrentham... Helen Keller who, besides being deaf since infancy, was also blind. Miss Keller's voice was high-pitched with a peculiar metallic ring, but her speech was remarkably clear.... Miss Keller came out of the porch to greet me and, asking me to sit beside her, told me to put the fore and middle fingers on her right hand on my lips. By that means she could understand everything I said. She spoke with enthusiasm of her aspirations to help others who were deaf and blind, and revealed that she was a socialist, repeatedly referring to socialism as the cure for the nation's ills."

Keller joined the Socialist Party of America and campaigned for Eugene Debs and his running-mate, Emil Seidel, in the 1912 Presidential Election. During the campaign Debs explained why people should vote for him: "You must either vote for or against your own material interests as a wealth producer; there is no political purgatory in this nation of ours, despite the desperate efforts of so-called Progressive capitalists politicians to establish one. Socialism alone represents the material heaven of plenty for those who toil and the Socialist Party alone offers the political means for attaining that heaven of economic plenty which the toil of the workers of the world provides in unceasing and measureless flow. Capitalism represents the material hell of want and pinching poverty of degradation and prostitution for those who toil and in which you now exist, and each and every political party, other than the Socialist Party, stands for the perpetuation of the economic hell of capitalism." Debs and Seidel won 901,551 votes (6.0%). This was the most impressive showing of any socialist candidate in the history of the United States.

A book on Keller's socialist views, Out of the Dark, was published in 1913. She later wrote "I had once believed that we are all masters of our fate - that we could mould our lives into any form we pleased. I had overcome deafness and blindness sufficiently to be happy, and I supposed that anyone could come out victorious if he threw himself valiantly into life's struggle. But as I went more and more about the country I learned that I had spoken with assurance on a subject I knew little about. I forgot that I owed my success partly to the advantages of my birth and environment. Now, however, I learned that the power to rise in the world is not within the reach of everyone." Hattie Schlossberg wrote in the New York Call: "Helen Keller is our comrade, and her socialism is a living vital thing for her. All her speeches are permeated with the spirit of socialism."

In 1912 Keller joined the theIndustrial Workers of the World (IWW). A socialist trade union group that opposed the policies of American Federation of Labour. Keller wrote later: "Surely the demands of the IWW are just. It is right that the creators of wealth should own what they create. When shall we learn that we are related one to the other; that we are members of one body; that injury to one is injury to all? Until the spirit of love for our fellow-workers, regardless of race, color, creed or sex, shall fill the world, until the great mass of the people shall be filled with a sense of responsibility for each other’s welfare, social justice cannot be attained, and there can never be lasting peace upon earth."

Keller also wrote articles for the socialist journal, The Masses. Keller, a pacifist, believed that the First World War had been caused by the imperialist competitive system and that the USA should remain neutral. After the USA declared war on the Central Powers in 1917, the journal came under government pressure to change its policy. When it refused to do this, the journal lost its mailing privileges. In July, 1917, it was claimed by the authorities that cartoons by Art Young, Boardman Robinson and Henry J. Glintenkamp and articles by Max Eastman and Floyd Dell had violated the Espionage Act. Under this act it was an offence to publish material that undermined the war effort. One of the journals main writers, Randolph Bourne, commented: "I feel very much secluded from the world, very much out of touch with my times. The magazines I write for die violent deaths, and all my thoughts are unprintable."

TheIndustrial Workers of the World also came under pressure for its opposition to the First World War. In 1914, one of the leaders of the IWW, Joe Haaglund Hill was accused of the murder of a Salt Lake City businessman. Convicted on circumstantial evidence and despite of mass protests, Hill was shot by a firing squad on 19th November, 1915. Whereas another IWW leader, Frank Little, was lynched in Butte, Montana. Another leader of the IWW, William Haywood, was arrested under the Espionage Act.

In an article published in The Liberator, Keller argued: "During the last few months, in Washington State, at Pasco and throughout the Yakima Valley, many IWW members have been arrested without warrants, thrown into bull-pens without access to attorney, denied bail and trial by jury, and some of them shot. Did any of the leading newspapers denounce these acts as unlawful, cruel, undemocratic? No. On the contrary, most of them indirectly praised the perpetrators of these crimes for their patriotic service! On August 1st, of 1917, in Butte, Montana, a cripple, Frank Little, a member of the Executive Board of the IWW, was forced out of bed at three o’clock in the morning by masked citizens, dragged behind an automobile and hanged on a railroad trestle. Were the offenders punished? No. A high government official has publicly condoned this murder, thereby upholding lynch-law and mob rule."

Newspapers that had previously praised Keller's courage and intelligence now drew attentions to her disabilities. The editor of the Brooklyn Eagle wrote that her "mistakes sprung out of the manifest limitations of her development." Keller was furious and wrote a letter of complaint to the newspaper. "At that time the compliments he paid me were so generous that I blush to remember them. But now that I have come out for socialism he reminds me and the public that I am blind and deaf and especially liable to error.... Socially blind and deaf, it defends an intolerable system, a system that is the cause of much of the physical blindness and deafness which we are trying to prevent."

In 1919 Keller appeared in an autobiographical film, Deliverance, in an attempt to spread "a message of courage, a message of a brighter, happier future for all men". Keller as a young girl was played by Etna Ross and as a young woman by Ann Mason. According to one critic: "In the final and most inspirational sequence, we see the real Helen Keller working tirelessly as a public figure to improve conditions for other blind people, and helping them to learn useful trades."

When Helen Keller decided after 1921 that her main work was to be devoted to raising funds for the American Foundation of the Blind, her activities for the socialist movement diminished but did not cease. Philip S. Foner has argued: "No matter what social cause she espoused, Keller was always on the radical side of the movement." As a left-wing socialist she disliked "parlor socialists" who quickly abandoned the struggle when the situation became difficult and later became "hopelessly reactionary."

In 1929 she published her book Mainstream. It included the following: "I had once believed that we are all masters of our fate - that we could mould our lives into any form we pleased ... I had overcome deafness and blindness sufficiently to be happy, and I supposed that anyone could come out victorious if he threw himself valiantly into life's struggle. But as I went more and more about the country I learned that I had spoken with assurance on a subject I knew little about. I forgot that I owed my success partly to the advantages of my birth and environment ... Now, however, I learned that the power to rise in the world is not within the reach of everyone."

Keller's childhood education was depicted in The Miracle Worker, a play by William Gibson, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1960. An Oscar-winning feature film in 1962, starring Anne Bancroft and Patty Duke, appeared two years later.

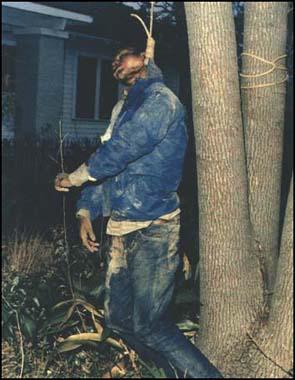

On this day in 1997 Frances Coleman published an article in Mobile Register on the lynching of Michael Donald

June 6 will be a sad day for Alabamians, whether their skins are white, black or brown. On that day -- the previous night, really, at 12:01 a.m. - the state of Alabama will electrocute Henry Francis Hays for beating a black man to death 16 years ago, and then hanging his body from a tree.

The execution will rip the scab from the old, deep, nasty wound of racism, which in the 20th-century South alternately heals and festers. It will fester again this week as residents of the Heart of Dixie re-live the brutal death of 19-year-old Michael Donald.

It is a story of contrasts: The murderer, a white man, grew up in a home filled with hate and violence. The victim was reared by a loving mother and doting older siblings.

Henry Hays knew what he was about that night, when he and a friend set out to kill a black man. Michael Donald, on the other hand, was innocently walking up the street on a spring evening in Mobile to buy some cigarettes, when fate delivered him into the white men's hands.

Most vivid, though, is the contrast between fiction and reality. Michael Donald was murdered -- beaten to death with a tree limb -- not in the 1930s or '40s, even in the 1960s, but in 1981. Such things weren't supposed to happen almost 30 years after the Supreme Court declared "separate but equal'' unconstitutional, and nearly 20 years after the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Nor were they supposed to happen in Mobile, which in the 1960s had somehow managed to avoid the racial violence that erupted in Selma and Birmingham.

Black men kidnapped and beaten, their bodies strung up in a tree? That was something that happened on the dark back roads of Dallas County or over in the Mississippi Delta, not in Alabama's second-largest city.

But hate crimes aren't constrained by time, place or suppositions. The reality is that Michael Donald died just 16 years ago at the hands of two Ku Klux Klansmen. So what if his death came years after lynchings were supposed to have ceased, and in a place not known for such things?

Barely out of childhood, he was a tragic, latter-day victim of a time when it was safer to be white -- when to be a black girl or woman was to invite sexual violence, and to be a black boy or man was to evoke daily disrespect, laced always with the potential for a fatal confrontation.

In the early hours of Friday morning, Henry Hays will pay for ending Michael Donald's life that day in 1981. He claims that he is innocent -- death row residents generally say that - but the evidence shows otherwise. Yet Hays is also a victim, albeit in a much different way than Donald.

Reared by an abusive father who beat his sons mercilessly, he was steered into a life of brutality and hate -- a life that one day included membership in the KKK. Hays learned little about love and less about tolerance.

Death penalty advocates tout execution as a deterrent to crime, and maybe it is in some respects. Henry Hays' death, though, will serve mostly as a sad commentary on a society that in 1997 - less than three years from the turn of the century - is having to electrocute a man for murdering another man, solely because of the color of his skin.

On this day in 2004 historian William Manchester died in Middletown, Connecticut. William Manchester was born in Springfield, Massachusetts, on 1st April, 1922. His father was a soldier who had been decorated for bravery during the First World War.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor Manchester joined the United States Marines. He was hospitalized after being wounded in the knee while fighting at Guadalcanal. Determined to take part in the fighting he hitchhiked to the front but soon afterwards he was blown up by a mortar round and was left for dead for over four hours. During the Second World War he won the Navy Cross, the Silver Star and two Purple Hearts.

In 1945 Manchester found work as a copyboy with the Daily Oklahoman. He then attended the University of Massachusetts and the University of Missouri. After graduating he worked under H. L. Mencken at the Baltimore Sun. This resulted in the book, Disturber of the Peace; The Life of H.L. Mencken (1951).

Manchester left journalism in 1955 to became Adjunct Professor of History and Writer-in-Residence at Wesleyan University. Books by Manchester published during this period include Shadow of the Monsoon (1956) and A Rockefeller Family Portrait (1959). Manchester, who had met John F. Kennedy during the Second World War, wrote Portrait of a President in 1962.

In 1964 Jacqueline Kennedy commissioned Manchester to write an account of the assassination of her husband. However, she was unhappy with the manuscript and managed to get Manchester to make several changes. Jacqueline was particularly upset by Manchester's portrayal of Lyndon B. Johnson. Despite the author's willingness to tone down his criticisms of Johnson she was still not happy with the final version on the book. Jacqueline tried to stop the book being published and offered Look Magazine $1m to kill its serialization (the magazine had paid $665,000 for the right to serialize the book).

The Death of a President was finally published in 1967 and it went on to sell 1.6m copies. Manchester next book, The Arms of Krupp (1968), was a look at the two German arms manufacturers, Gustav Krupp and Alfried Krupp. The book explored the Krupp family's links to Adolf Hitler and his government. Although Krupp, was convicted of war crimes at the Nuremburg trials he was released by John J. McCloy, the high commissioner in American occupied Germany, in 1951. Manchester argued that Krupp was freed because he was considered essential to the Cold War effort.

Other books by William Manchester included The Glory and the Dream: A Narrative History of America, 1932-1972 (1974), American Caesar: Douglas MacArthur (1978), Goodbye, Darkness: A Memoir of the Pacific War (1980), Remembering Kennedy (1983), The Last Lion: Winston Spencer Churchill (1983), Magellan (1994) and No End Save Victory (2001).