The Coal Industry: 1600-1925

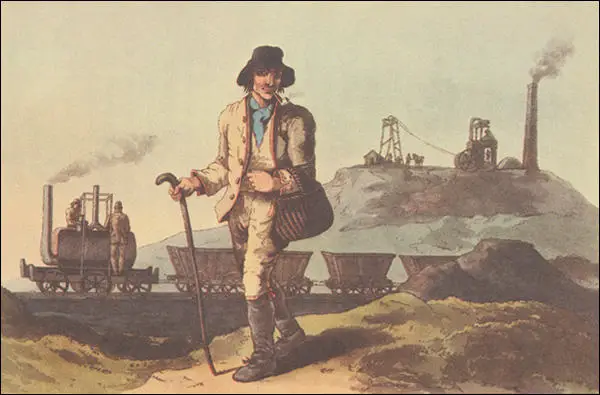

In the 17th century most coal was taken from small and shallow "bell pits". Pits were often on common land and run by small groups of families. These families worked in teams. Hewers used a pick or crowbar to remove the coal from the seam while women and children carried the coal to the surface. Pits seldom employed more than forty of fifty miners and often less than twenty. (1)

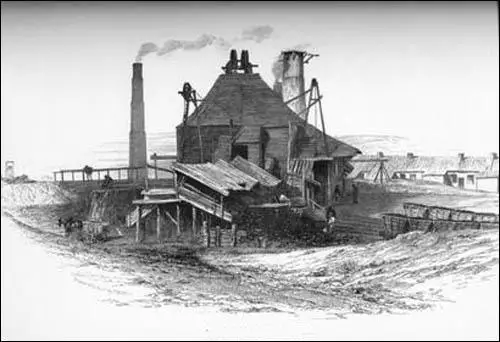

As surface deposits became exhausted, coal miners were forced to go deeper into the ground. One of the major problems of mining for coal in the 17th and 18th centuries was flooding. Colliery owners used several different methods to solve this problem. These included pumps worked by windmills and teams of men and animals carrying endless buckets of water. (2)

Thomas Newcomen worked on developing a machine to pump water out of the mines. He eventually came up with the idea of a machine that would rely on atmospheric air pressure to work the pumps, a system which would be safe, if rather slow. The "steam entered a cylinder and raised a piston; a jet of water cooled the cylinder, and the steam condensed, causing the piston to fall, and thereby lift water." (3)

In 1763 James Watt was sent a steam engine produced by Thomas Newcomen to repair. Although many mine-owners used Newcomen's steam-engines, they constantly complained about the cost of using them. The main problem with it was they needed a great deal of coal and were therefore expensive to run. While putting it back into working order, Watt attempted to discover how he could make the engine more efficient. (4)

The development of Watt's steam engine resulted in a large increase in the demand for coal. Large landowners, such as the Henry Somerset, 5th Duke of Beaufort, in Wales and the Douglas Hamilton, 8th Duke of Hamilton in Scotland, began to take an interest in coal-mining. It now became profitable for these landowners to employ miners to dig coal from seams that were well over 500 feet below the surface. New pits were opened up in South Wales, Scotland, Lancashire and Yorkshire, and output increased from 2,600,000 tons in 1700 to over 10,000,000 in 1795. (5) By 1800 Britain produced about 90% of the world output of coal. Its nearest competitor, France, produced less than a million tons. (6)

The industrial revolution created an increased demand for coal. Alan Ereira, the author of The People's England (1981) points out that this had important consequences for areas with large amount of coal under the ground. "A new pit required new colliers and a new village to house them. Colliery villages were remote, isolated communities, regarded by the world outside as savage encampments. The new villages were inhabited by migrants; the agricultural parts of Durham generally had a shrinking population, but from 1730 to 1801 the population of the country rose from 97,000 to 160,000, as people came to the pits. Pitmen's children, according to a report in 1800, were put down the mine when they were 7 or 8 years old, and sometimes as young as 6." (7)

Combination Laws

In the eighteenth-century colliers in every coal-mining area attempted to form unions. Colliery owners refused to negotiate with these organizations and the colliers were invariably defeated. During this period miners obtained a reputation for militancy and were accused of being followers of the revolutionary doctrines of Tom Paine. As employers were hostile to these early trade unions, their meetings were often held in secret. (8)

This involved the taking of secret oaths: "The oath was taken at the time of initiation into the union, usually in a private room at a tavern at eight or nine o'clock in the evening. On one side of the apartment was a skeleton, above which a drawn sword and a battle axe were suspended, and in front stood a table upon which lay a bible. The officers of the union wore surplices and addressed each other by their titles of president, vice-president, warden, principal conductor, and inside and outside tiler. The new members were blindfolded for parts of the ceremony, which included the singing of hymns and the recitation of prayers." (9)

In 1799 and 1780 William Pitt, the Prime Minister, decided to take action against political agitation among industrial workers. With the help of William Wilberforce, the Combination Laws was passed making it illegal for workers to join together to press their employers for shorter hours or may pay. As a result trade unions were thus effectively made illegal. In theory, the terms of the act applied to combinations of employers as well as to trade unions. "Whatever the letter of the law, it clearly applied only to employees." (10)

A. L. Morton has pointed out in his book, A People's History of England (1938): "These laws were the work of Pitt and of his sanctimonious friend Wilberforce whose well known sympathy for the negro slave never prevented him from being the foremost apologist and champion of every act of tyranny in England, from the employment of Oliver the Spy or the illegal detention of poor prisoners in Cold Bath Fields gaol to the Peterloo massacre and the suspension of habeas corpus." (11)

Explosions in Mines

These deep mines created serious safety problems. Miners had always suffered from the dangers of collapsing roofs. These new deeper mines meant additional problems. Coal seams deep under the ground emitted a gas that the miners called firedamp. As this gas was highly inflammable, it was extremely hazardous for miners to carry candles with them underground. Every year large numbers of miners were killed by gas explosions.

In 1812, an explosion at Felling Colliery near Gateshead killed 92 miners. People from the local community formed a society for preventing accidents. The society asked the chemist, Humphry Davy, if he could help reduce the number of miners being killed from gas explosions. After analyzing the fire-damp, Davy discovered that it was a mixture of carbon and hydrogen. With this information Davy was now able to invent a lamp that would not cause explosions. (12)

However, The Spectator magazine pointed out nearly forty years later that the Davy lamp did not have the desired consequences: "The mineral fuel which constitutes so great a source of our national wealth is not extracted from the earth without a fearful sacrifice of life; either cut off suddenly, or slowly, but as surely, destroyed by inhaling the poisonous gases of the mines. Scarcely a week passes without fatal explosions, of which little notice is taken beyond the immediate scenes of the calamities; nor is it till some thirty or forty human beings have been killed at one flash that public attention is aroused whilst the thousands who are sent to premature graves by the daily operating effects of the insidious atmospheric poison are altogether unminded. The 'safety-lamp,' which in its day was hailed as an important boon conferred by science on the miner, has in practice proved a fatal gift. It has enabled the proprietors of mines to obtain coal in workings that were too 'fiery' to be approached with unprotected flame, and the miner is compelled to breathe an atmosphere which the wire-gauze of his lamp alone prevents from exploding." (13)

It has been argued that the Davy lamp was "the most striking example of the way in which capitalists were able to turn the labours of the humanitarian to their advantage... The lamp was quickly and widely adopted, Davy himself refusing to take any royalties for what he regarded as his gift to humanity. The actual result was an increase in the number of accidents since the owners were able to open up deeper and more dangerous seams, and, in many cases, the existence of the lamp was made an excuse for not providing proper ventilation." (14)

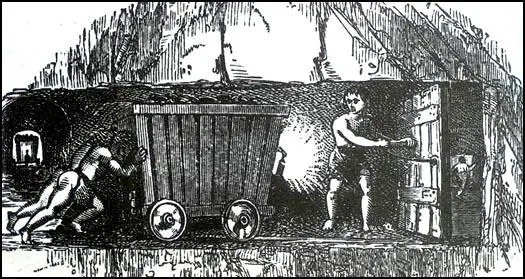

The problem of ventilation was dealt with by having at least two shafts in every pit. A furnace was situated at the bottom of one of these shafts. The hot air rising from the furnace drew fresh air down the other shaft. This fresh air was then directed through the tunnels in the mine by the opening and dosing of trap doors. This job, which required sitting in total darkness, was usually done by children of four or five years old. (15)

Black Lung Disease

Poor ventilation also created long-term health problems. The air underground contained high levels of coal dust. In 1813, Dr. George Pearson reported that in the course of many post-mortem inspections he discovered that "at the age of about twenty twenty-years the lungs have a mottled or marbled appearance" and by the age of 65 onwards they appeared almost uniformly black. At the time the condition became known as "black lung disease" or "black spit". Later the medical profession gave it the name "pneumoconiosis". (16)

he was buried underground without food or light for twelve days.

This build-up of coal dust in the lungs resulted in a variety of different health problems. Many miners suffered from emphysema and bronchitis. Lungs saturated with coal dust could not function properly and this often led to heart failure. The polluted underground atmosphere was also partly responsible for large numbers of miners dying at an early age. Isabel Hogg lost her husband from this disease: "Collier-people suffer much more than others - my good man died nine years since with bad breath; he lingered some years and was entirely off work 11 years before he died." (17)

Child Labour

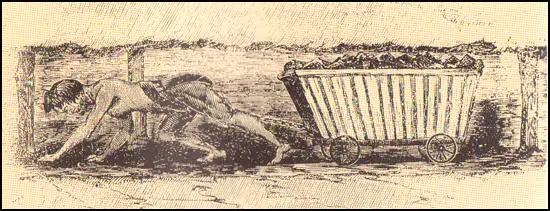

Work in coalmines was both hard and dangerous. Coal seams varied in thickness from eighteen inches in Durham to about seven feet in Yorkshire. Narrow seams meant the miners worked in very confined spaces. David Douglass pointed out: "The thin seams of Durham are a nightmare... Crawing down the seam, only inches would separate the roof from your prostate body, your head would be turned to the side, flat against the floor with maybe a two-inch space above before you made contact with the roof." (18)

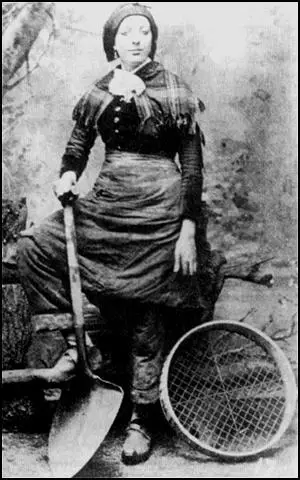

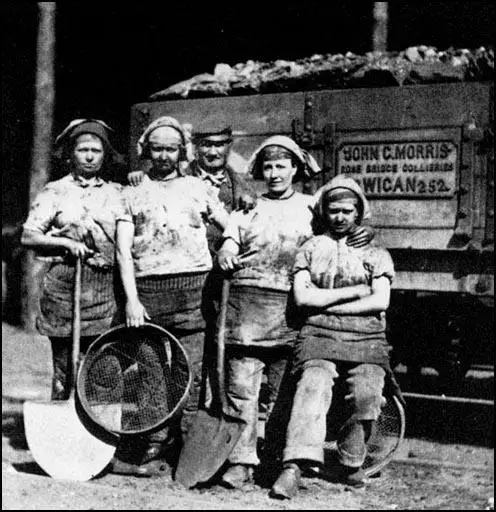

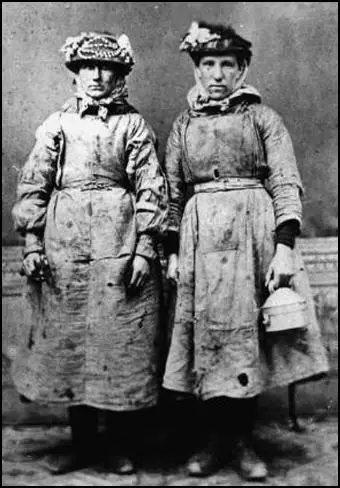

Where possible, pit ponies were used to carry the coal. However, in narrow seams, women and children had the job of carrying the coal while crawling on their hands and knees. Child labour became common mines. "Children were chained, belted, harnessed like dogs in a go-cart, black, saturated with wet, and more than half-naked - crawling upon their hands and feet, and dragging their heavy loads behind them - they present an appearance indescribably disgusting and unnatural." (19)

According to research carried out at the beginning of the 19th century showed that children who worked in the industry spent most of their life underground: "In 1800 the working day for small boys started at 2 a.m., when the caller-out came round. They were down the pit by three o'clock and did not return until after eight at night. They spent the time minding a door. As pits went deeper, and underground workings became more extensive, it was important to control the ventilating currents of air." (20)

Alexander Macdonald started working at New Monkland, in Lanarkshire, in 1835: "I entered the mines at about eight years of age. The condition of the miner's boy then was to be raised about 1 o'clock or 2 o'clock in the morning if the distance was very far to travel, and at that time I had to travel a considerable distance, more than three miles. We remained at the mine until 5 and 6 at night. It was an ironstone mine, very low, working about 18 inches, and in some instances not quite so high. Then I moved to coal mines. There we had low seams also, very low seams. There was no rails to draw upon, that is, tramways. We had leather belts for our shoulders. We had to keep dragging the coal with these ropes over our shoulders, sometimes round the middle with a chain between our legs. Then there was always another behind pushing with his head." (21)

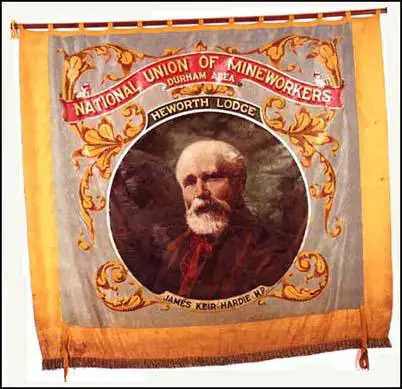

Keir Hardie found work in the small mining village of Newarthill, working for "twelve or fourteen hours a day". Initially he worked as a trapper. "The work of a trapper was to open and close a door which kept the air supply for the men in a given direction. It was an eerie job, all alone for ten long hours, with the underground silence only disturbed by the sighing and whistling of the air as it sought to escape through the joints of the door." (22)

Thomas Burt began work as a trapper boy in Haswell Colliery when he was ten years old. He worked in a team with his uncle, Thomas Weatherburn. "He was a strong, skilful hewer. For many years he had been an engine-man, and had been tempted, or starved, into the coalmines that he might get higher pay. He worked with the steady stroke, the composure, and the effectiveness of a perfect machine... The hewer is paid by the ton. His earnings, therefore, depend partly upon his industry, strength, and skill, and partly upon his luck. In extreme cases, I have known two or three shillings a day difference between one working-place and another". (23)

The children were often beaten for making mistakes. George Anderson was an orphan who worked as the Gosforth Colliery. He was paid 4p a day for his work. "In the night shift I go down at 4 p.m. and come up about 4.30 in the morning. I'm often sleepy. I got my hammers (beaten) twice by being asleep. The putters (men who handled the trams of coal) beat me with their soam-sticks (wooden handles) and hurt me and made me cry because I did not open the doors for them. My door is nearly 2½ miles in. The pit looses (closes) at half past three and though I run I am nigh an hour getting out." (24)

Eric Hopkins, the author claims A Social History of the English Working Classes (1979) claims that the children working in mines were very badly treated: "Children were often beaten as they were in other industries, but in the pits a good deal of cruelty might take place in secret... It was also alleged that immorality was rife in some pits. Men sometimes worked quite naked alongside women who were commonly naked from the waist up, so that (it was said) the women became debased and degraded." (25)

Jane Peacock Watson, a coal-bearer from West Linton was interviewed at the age of forty. She began work as a child and was forced to make her children work underground. "I have wrought in the bowels of the earth 33 years and have been married 23 years, and had nine children. Six are alive, three died of typhus a few years since and I have had two dead born. They were so from the oppressive work. A vast of women have dead children... I have always been obliged to work below till forced to go home to bear the bairn (child). We return as soon as we are able, never longer than 10 or 12 days, many less if they are needed. It is only horse work, and ruins the women. It crushes the haunches, bends their ankles, and makes them old women at 40. Women so soon get weak that they are forced to take the little ones down (the mine) to relieve them; even children of six years of age do much to relieve the burthen". (26)

Children's Employment Commission

A serious accident in 1838 at Huskar Colliery in Silkstone, revealed the extent of child labour in the mines. A stream overflowed into the ventilation drift after violent thunderstorms causing the death of 26 children (11 girls aged from 8 to 16 and 15 boys between 9 and 12 years of age). The story of the accident appeared in London newspapers and Queen Victoria put pressure on her prime minister, Lord Melbourne, to hold an enquiry into the working conditions in Britain’s factories and mines. (27)

The investigation was chaired by Anthony Ashley-Cooper (Lord Ashley) and over the next couple of years interviewed a large number of people working in Britain's factories and mines. This included eight-year-old Sarah Gooder: "I'm a trapper in the Gawber pit. It does not tire me, but I have to trap without a light and I'm scared. I go at four and sometimes half past three in the morning, and come out at five and half past (in the afternoon).. I never go to sleep. Sometimes I sing when I've light, but not in the dark; I dare not sing then. I don't like being in the pit.... I would like to be at school far better than in the pit." (28)

Where possible, wagons carrying coal, were drawn by horses, and driven by children. However, in low and narrow underground passages, women were used to pull carts full of coal: Betty Harris, worked in a pit in Little Bolton in Lancashire: "I have a belt round my waist, and a chain passing between my legs, and I go on my hands and feet... I have drawn till I have had the skin off me; the belt and chain is worse when we are in the family way." Ann Eggley was employed at Thorpe's Colliery: "The work is far hard for me. Sometimes when we get home at night we have not power to wash ourselves... Father said last night it was both a shame and disgrace for girls to work as we do, but there is nothing else for us to do." (29)

Financial circumstances meant that women continued to do this work while they were pregnant. Betty Wardle explained how she had worked in a pit since she was six years old. One of her children was born while she was underground. "I had a child born in the pits, and I brought it up the pit-shaft in my skirt." When the interviewer questioned the truth of this statement, she replied: "Ay, that I am; it was born the day after I was married, that makes me to know." (30)

Isabel Wilson was 38 years old when she gave evidence to the Children's Employment Commission: "When women have children... they are compelled to take them down early. I have been married 19 years and have had 10 bairns (children); seven are in life. I was a carrier of coals, which caused me to miscarry five times from the strains, and was ill after each. My last child was born on Saturday morning, and I was at work on the Friday night." (31)

Thomas Wilson, the owner of three collieries in the Barnsley area blamed the miners for the problem. "The employment of females of any age in and about the mines is most objectionable, and I should rejoice to see it put an end to; but in the present feeling of the colliers, no individual would succeed in stopping it in a neighbourhood where it prevailed, because the men would immediately go to those pits where their daughters would be employed... The only way effectually to put an end to this and other evils in the present colliery system is to elevate the minds of the men; and the only means to attain this is to combine sound moral and religious training and industrial habits with a system of intellectual culture much more perfect than can at present be obtained by them."

Wilson warned against the idea that the government should pass legislation to protect these women: "I object on general principles to government interference in the conduct of any trade, and I am satisfied that in mines it would be productive of the greatest injury and injustice. The art of mining is not so perfectly understood as to admit of the way in which a colliery shall be conducted being dictated by any person, however experienced, with such certainty as would warrant an interference with the management of private business. I should also most decidedly object to placing collieries under the present provisions of the Factory Act with respect to the education of children employed therein." (32)

The Children's Employment Commission published its first report on mines and collieries in 1842. The report caused a sensation when details appeared in newspapers. Ivy Pinchbeck pointed out: "A wider interest was secured for the Report by the woodcuts, since they captured the imagination of many who might not have been tempted to read an ordinary Blue Book. Almost more than by their heavy labour, Victorian England was shocked and horrified by accounts of the naked state of some of the workers." (33)

The majority of people in Britain were unaware that women and children were employed as miners. However, nearly three-quarters of the petitions to Parliament were against the proposed regulation of child labour. As many as 86 per cent of petitions came from the technologically backward districts where higher levels of child labour existed and employer's feared that the change of law would lead to lower profits. (34)

Within a week of the report being published Lord Ashley gave notice of the Mines and Collieries Bill that he intended to take through Parliament. He wrote in his diary: "The government cannot, if they would refuse the bill of which I have given notice, to exclude females and children from the coal-pits - the feeling in my favour has become quite enthusiastic; the press on all sides is working most vigorously." (35)

Ashley introduced his Bill in a long eloquent speech. "Their labour... is wasteful and ruinous to themselves and their families... They know nothing that they ought to know, they are rendered unfit for the duties of women by overwork, and become utterly demoralized. In the male the moral effects of the system are very sad, but in the female they are infinitely worse, not alone upon themselves, but upon their families, upon society, and, I may add, upon the country itself. It is bad enough if you corrupt the woman, you poison the waters of life at the very fountain." (36)

Two days later he wrote in his diary: "On the 7th, I brought forward my motion - the success has been wonderful, yes, really wonderful - for two hours the House listened so attentively you might have heard a pin drop, broken only by loud and repeated marks of approbation - at the close a dozen members at least followed in succession to give me praise, and express their sense of the holy cause... Many men, I hear shed tears." (37)

Charles Vane, 3rd Marquess of Londonderry, an owner of several collieries, led the opposition in the House of Lords. He declared that some seams of coal required the employment of women; and certain pits, which could not afford to pay men's wages must either employ women or close down. He ended his speech by claiming that he believed "that the exclusion of female labour would be an injurious manner." (38)

The measure was passed by the House of Lords on 5th July, 1842. As a result of this legislation all females and boys under ten years old were banned from working underground in coal mines. However, only one inspector was appointed for the entire country and so colliery owners continued to employ women and children in mines. The inspector later admitted that he would only enforce the regulations where a child had been killed in the underground accident. Even then, the fines imposed would often fall "not upon the colliery owner, but upon the father or the guardian of the boy". (39)

In 1850 the Commissioner of Mines, Hugh Seymour Tremenheere, estimated that "200 women and girls were still working in collieries in South Wales, many of whom were only eleven or twelve years of age". (40) The government therefore increased the number of inspectors. However, Lord Ashley admitted that underground inspection was "altogether impossible, and, indeed, if it were possible it would not be safe... I for one, should be very loath to go down the shaft for the purpose of doing some act that was likely to be distasteful to the colliers below". (41) In his report of 1854, Tremenheere, reported "two instances where persons attempted inspection of their own accord, were maltreated, and very nearly lost their lives." (42)

Another difficulty was that parish records of baptisms did not contain a record of birth dates, "This posed huge problems for the inspectors who were frequently presented with unofficial and often falsified forms of evidence by parents... Some suggested the examination of children's teeth as a guide to the ages of applicants, whereas others urged the use of statistical evidence of average heights. Nothing could prevent the frequent practice of parents fraudulently presenting older siblings in order to obtain certificates for their younger offspring." (43)

Peter Kirby, the author of Child Labour in Britain, 1750-1870 (2003), has pointed out that many mine owners stopped employing young children, not because it was illegal, but because they were considered to be inefficient. "In the complicated ventilation systems of larger pits, young and inexperienced 'trappers' were often held responsible for causing explosions by leaving open their ventilation doors, and the exclusion of the very young children from complex ventilation systems, where it was applied, had a tangible effect in reducing accidents from explosions."

He then goes onto argue that "in less advanced colliery districts, where pits were small or where haulage in narrow seams was necessary and demand for child workers relatively higher, colliery owners were afforded virtual immunity from inspection and prosecution under the Act." In other words, "the Mines Act tended to be applied only where it was in the interests of colliery owners". (44)

It was not until 1872 that the age of boys who could work in the coalmines was raised to 12 and eventually to 13 in 1903. Even so, there is a great deal of evidence to show that colliery owners continued to employ children illegally for many years afterwards. (45)

Miners' Federation of Great Britain

During the early stages of the industrial revolution, coal-mining techniques remained primitive and unmechanized. Hewers hacked out the coal from the seams with their picks at the coal face. Putters supplied the face workers with empty tubs and then pushed the full ones from the coal face to the wagons for hauling to the shaft. As a result of the needs of industry, the output of coal between 1830 and 1850 trebled from 15 million tons to 49 million tons. (46)

The increasing demand for coal improved the bargaining position of the colliers and miners in Northumberland and Durham joined together to gain a reduction in hours and the abolition of the truck system. This encouraged miners from other parts of the country to form district associations.

With the development of the railways in the 1840s, it became increasing difficult for district organizations to apply the necessary pressure on colliery owners. In 1842 colliers formed the Miners Association of Great Britain and Ireland. Certain areas such as Yorkshire and East Midlands failed to join and the mass importation of strike-breakers during industrial disputes continued to undermine local unions.It is estimated that by 1851 the industry employed 216,000. (47)

The Miners Association campaigned against dangerous working conditions. Accidents in shafts caused by rope and chain breakages, flooding, fires and roof falls continued to kill large numbers of miners. Official statistics were not kept, and powerful colliery owners were often successful at persuading local newspapers not to report the deaths of coal-miners. (48)

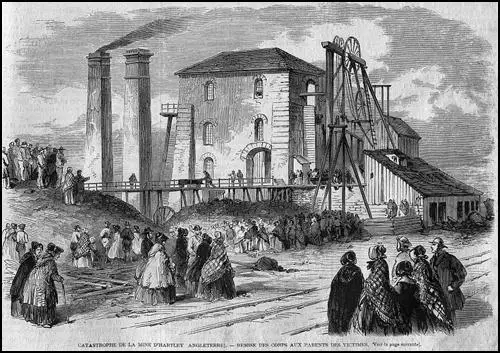

By studying all the statistics that are available, one historian has calculated in some collieries in the 19th century, workers had a 50% chance of being killed in a mining accident. One of the worst mining disaster was at the Hartley Colliery, near Seaton Delaval, on 16th January 1862, when 204 men were killed when the beam of the pit's pumping engine broke and fell down the shaft, trapping the men below. (49)

The Trades Unions were very dissatisfied with the attitude of the government to the legal position of Trade Unionism. In 1869, John Stuart Mill, established the Labour Representation League (LRL) and started a national campaign to secure the return of working men to the House of Commons. The Liberal Party leadership accepted his arguments and at the 1874 General Election the LRL put up 12 Lib-Lab candidates, and of these Thomas Burt and Alexander MacDonald were elected at Morpeth and Stafford respectively. (50)

In May 1879, Scottish mine owners combined to force a reduction of wages. Keir Hardie was appointed Corresponding Secretary of the miners, a post which gave him opportunity to get in touch with other representatives of the mine workers throughout southern Scotland. In the summer of 1880, the Hamilton miners defied their union and went on strike against a wage reduction. The strike was crushed, but Hardie was appointed secretary for the recently formed Ayrshire Miners' Union. (51)

After the passing of the 1884 Reform Act most miners could vote in parliamentary elections. Colliery trade unionists were selected as Liberal Party candidates in several mining constituencies and six of them were elected to Parliament: Charles Fenwick (Wansbeck), William Crawford (Mid-Durham); John Wilson (Houghton); Ben Pickard (Normanton) and William Abraham (Rhondda).

After the 1885 General Election there were eleven of these Liberal-Labour MPs. William Gladstone, the prime minister, offered one of them, Henry Broadhurst, a former stonemason, the post of Under-Secretary at the Home Office. When Broadhurst accepted the post he became the first working man to become a government minister. Broadhurst's loyal support of the Liberal government upset some trade union leaders. When Broadhurst argued against the eight-hour day, Hardie remarked that the minister was more Liberal than Labour. (52)

In 1886 Keir Hardie was appointed secretary of the Scottish Miners' Federation. The following year, Hardie began publishing a monthly newspaper called The Miner. Its first number appeared in January, 1887, and it was published for two years, with Hardie supplying about a third of its content: "It was a very remarkable paper, and to those who are fortunate enough to possess the two volumes, it mirrors in a very realistic way the social conditions of the collier folk of that time, and also throws considerable light on the many phases and aspects of the general Labour movement in the days when it was gropingly feeling its way through many experiments and experiences towards political self-reliance and self-knowledge". (53) The newspaper advocated a Scottish miners' federation and attacked the coal-owners for the bloody suppression of the Lanarkshire workers that took place that year. (54)

In the summer of 1888 the price of coal began to rise. All over Britain miners began to talk about the need for a pay increase. When colliery owners rejected the claims of the Yorkshire Miners' Association, its leader, Ben Pickard, sent out a circular inviting all miners "to attend a conference for the purpose of considering the best means of securing a 10% advance in wages and of trying to find common ground for action." The Conference took place in Derby on 29th October, 1888 where the formation of a new national union was discussed but no agreement was reached.

Ben Pickard called another conference in Newport on 26th November 1889. Pickard selected Newport as it was fiftieth anniversary of the Chartist Newport Uprising. Those attending included Keir Hardie, Thomas Burt, Herbert Smith, Thomas Ashton, Enoch Edwards and Sam Woods. At the conference it was decided to form the Miners' Federation of Great Britain (MFGB). Officers elected included Pickard (president), Woods (vice-president), Edwards (treasurer) and Ashton (secretary). It initially had 36,000 members. (55)

Under Pickard's leadership the MFGB was a great success. His biographer, John Benson, has argued: "By 1893, the federation's 200,000 members represented nearly a third of the mining workforce (and about a seventh of all British trade unionists); seven years later the federation numbered among its members nearly half of all miners (and a sixth of all trade unionists) in the country." (56)

From the beginning the Miners' Federation of Great Britain attempted to have all the colliers' trade unions united in a single body. South Wales joined in 1898 but Northumberland and Durham, with a quarter of all Britain's miners, refused to become part of the MFGB. Negotiations continued and both areas agreed to join. The membership of the MFGB was now over 600,000. This gave the MFGB tremendous strength in the Trade Union Congress, as the organization represented over a quarter of all trade unionists in Britain.

By the beginning of the 20th century coal was the overwhelmingly predominant source of heat, light, and power in the expanding economy. "The position of the British coal-mining industry... represented a peak of economic achievement. In spite of anxieties about industrial relations, commercial competitiveness and labour productivity, coal occupied a supreme position in the British economy." (57)

The MFGB suffered a set-back when in 1901 the Taff Vale Railway Company sued the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants for losses during a strike. As a result of the case the union was fined £23,000. Up until this time it was assumed that unions could not be sued for acts carried out by their members. This court ruling exposed trade unions to being sued every time it was involved in an industrial dispute. It has been argued that the "Taff Vale case came as the culmination of a whole series of legal decisions in the last decade of the nineteenth century which undermined trade unions right to strike". (58)

The 1906 General Election gave greater power to the mine workers. The old enemy, the Conservative Party, won only 156 seats. The Liberal Party, with 397 seats (48.9%), formed the next government. The Labour Party did well, increasing their seats from 2 to 29. In the landslide victory Arthur Balfour, the leader of the Tories, lost his seat as did most of his cabinet ministers. Margot Asquith wrote: "When the final figures of the Elections were published everyone was stunned, and it certainly looks as if it were the end of the great Tory Party as we have known it." (59)

Some members of the government thought, including the prime minister, Henry Campbell-Bannerman, that Parliament should pass legislation which would protect trade unions. When introducing the Trades Disputes Act, which removed trade union liability for damage by strike action, Campbell-Bannerman, argued: "I have never been, and I do not profess to be now, very intimately acquainted with the technicalities of the question, or with the legal points involved in it. The great object then was, and still is, to place the two rival powers of capital and labour on an equality so that the fight between them, so far as fight is necessary, should be at least a fair one." (60)

In 1910 a strike broke out at the Cambrian Combine, where its miners wanted parity with colliers working richer seams. Keir Hardie and Tom Mann arrived in the area to give the strikers their support. On the 8th November, strikers became involved in hand-to-hand fighting with the Glamorgan Constabulary. The home secretary, Winston Churchill, responded by sending in the British Army to "defend the mine-owners property". Hardie responded by claiming that "the bringing in of troops as typical of the militarism of the so-called Liberal reformers". (61)

Arthur J. Cook played a significant role in the strike. He also became a supporter of a new political creed called syndicalism. Cook argued "that the power of the workers to organise or disrupt their own production – their power to strike – was the only power which the owners were likely to recognise: the only power which might change the miners’ conditions and the only power which could eventually change society". This was in direct opposition to the Labour Party that advocated a parliamentary approach to socialism. (62)

Cook joined forces with two other syndicalists, Noah Ablett and Stephen Owen Davies, to produce the pamphlet, The Miners' Next Step (1912). It stated: "That the organization shall engage in political action, both local and national, on the basis of complete independence of, and hostility to all capitalist parties, with an avowed policy of wresting whatever advantage it can for the working class... Today the shareholders own and rule the coalfields. They own and rule them mainly through paid officials. The men who work in the mine are surely as competent to elect these, as shareholders who may never have seen a colliery. To have a vote in determining who shall be your fireman, manager, inspector, etc., is to have a vote in determining the conditions which shall rule your working life. On that vote will depend in a large measure your safety of life and limb, of your freedom from oppression by petty bosses, and would give you an intelligent interest in, and control over your conditions of work. To vote for a man to represent you in Parliament, to make rules for, and assist in appointing officials to rule you, is a different proposition altogether." (63)

Despite the growth of industrial action, the coal industry continued to grow. In 1913 an estimated 1.1 million men and boys working in the industry and that they produced 287 million tons of fuel. Although the United States and Germany were major competitors, the "British coal industry was still a dominant international force! Its annual production was equivalent to some 23 per cent of the world's supply... Britain's overseas shipments accounted for no less than 55 per cent of all coal traded internationally." (64)

First World War

On the outbreak of the First World War, the former miner's leader, Keir Hardie tried to organize a national strike against Britain's participation in the war. He issued a statement that argued: "The long-threatened European war is now upon us. You have never been consulted about this war. The workers of all countries must strain every nerve to prevent their Governments from committing them to war. Hold vast demonstrations against war, in London and in every industrial centre. There is no time to lose. Down with the rule of brute force! Down with war! Up with the peaceful rule of the people!" (65)

Arthur J. Cook, a leading figure in the MFGB in South Wales was a strong opponent of the war. He was especially angry about the willingness of the government to spend such large sums on the military where they had been slow to deal with the problems of working-class poverty. In one article for the Porth Gazette, he argued "we must do our duty as trade unionists and as citizens to force the Government, who in one night could vote £100 millions for destruction of human life to see that justice is meted out to these unfortunates". (66)

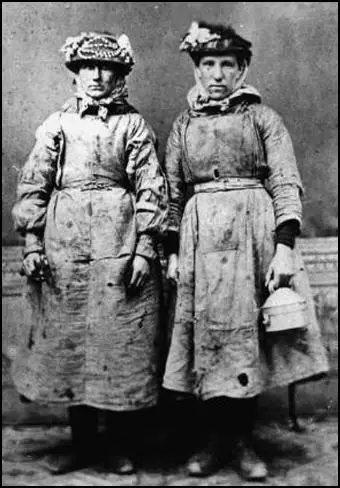

It was very important for the government to avoid strikes during the war and with the help of the Labour Party and the Trade Union Congress an "Industrial Truce" was announced. A further agreement in March 1915, committed the unions for the duration of hostilities to the abandonment of strike action and the acceptance of government arbitration in disputes. In return the government announced its limitation of profits of firms engaged in war work, "with a view to securing that benefits resulting from the relaxation of trade restrictions or practices shall accrue to the State". (67) A. J. P. Taylor, has described these measures as "war socialism". (68)

At the beginning of the war miners were the largest single group of industrial workers in Britain. Coal production increased during the first few months of the conflict. This was mainly due to a greater commitment of the labour force in maximizing output. However, by March 1915, 191,170 miners joined the armed forces. "This was 17.1 per cent of the men engaged in the industry at the beginning of the war and constituted approximately 40 per cent of the miners of military age, 19-38." (69)

The Munitions of War Act was passed by Parliament in 1915 and provided for compulsory arbitration and virtually prohibited all strikes and lockouts. The Act also prohibited any change in the level of wages and salaries in "controlled" establishments without the consent of the Minister of Munitions. In those industries important to the war effort, it forbade workers in those establishments to leave their job without a "certificate of leave". The Labour movement was strongly opposed to this measure but was endorsed by the leadership of the TUC and the Labour Party. (70)

In March 1915 the Miners' Federation of Great Britain (MFGB) demanded a twenty per cent wage increase to compensate for inflation. The coal owners refused to discuss a national wage rise, and negotiations reverted to the districts. Agreements were arrived at satisfactorily in most areas, but in South Wales the owners were only willing to offer ten per cent. In July the miners in South Wales went on strike. (71)

Walter Runciman, the President of the Board of Trade, met with miners leaders but was unable to obtain an agreement. H. H. Asquith, considered using the Munitions of War Act, which effectively made strike action illegal. David Lloyd George warned against this and he negotiated a settlement that quickly conceded nearly all of the miners demands. This included a 18½ per cent wage increase. (72)

Lloyd George now made regular visits to British mining areas giving patriotic speeches about the importance of coal for the war effort and stressing that the miners should work harder in order to maximize output. He argued that "every extra wagon load would bring the war to a more speedy conclusion". In one speech he pointed out: "In peace and war King Coal is the paramount lord of the industry... In wartime it is life for us and death for our foes." (73)

In November 1916, another strike over pay took place in Wales. This time the government agreed to Runciman's proposal that "the government by regulation under the Defence of the Realm Act assume power to take over any of the collieries of the country, the power to be exercised in the first instance in South Wales". It was decided to take full control over shipping, food and the coal industry. Alfred Milner was appointed as Coal Controller. It has been argued that "instigating control of one of Britain's major staple industries was an unprecedented move by the state." (74)

Milner issued his first report on 6th November 1916 and recognizing the gravity of the problem by recommending the immediate freezing of coal prices and suggesting the establishment of a Royal Commission to considering the future of the coal industry. Lloyd George argued that "the control of the mines should be nationalized as far as possible". (75) He acknowledged that this was a new political development and commented that the government had a choice, it needed "to abandon Liberalism or to abandon the war". (76)

The government became very concerned about the activities of Arthur J. Cook, the leader of the miners in the Rhondda. The high casualty-rate during 1916, especially at the Somme Offensive, prompted the government to draft men from essential industries who had hitherto been exempt from conscription. It was decided to take 20,000 miners from the pits and put them in the army. Cook took steps to obstruct the military's attempts to recruit men and posted notices at the local collieries advising miners to disobey instructions to report for army examination. Captain Lionel Lindsay, Chief Constable of Glamorgan applied to the Home Office to have him prosecuted but worried it would result in a strike the suggestion was turned down. (77)

At a mass meeting on 15th April 1917, Cook called for "peace by negotiations". In an article in The Merthyr Pioneer, he argued: "I am no pacifist when war is necessary to free my class from the enslavement of capitalism... As a worker I have more regard for the interests of my class than any nation. The interests of my class are not benefited by this war, hence my opposition. Comrades, let us take heart, there are thousands of miners in Wales who are prepared to fight for their class. War against war must be the workers' cry." (78)

Arthur J. Cook welcomed the Russian Revolution and according to a MI5 agent he told one meeting: "To hell with everybody bar my class. To me, the hand of the German and Austrian is the same as the hand of my fellow-workmen at home. I am an internationalist. Russia has taken the step, and it is due to Britain to second the same and secure peace and leave the war and its cost to the capitalist who made it for the profiteer." (79)

In November, 1917, the Chief Constable of Glamorgan once again reported the activities of Cook to the Home Office: "It was only reported to me by a Recruiting Officer last night that A. J. Cook, the agitator from the Lewis-Merthyr Colliery, Trehafod, Glamorgan, who I have frequently reported for disloyal utterances, without success, openly declared, whilst denouncing the Recruiting Authorities at Pontypridd, that if he decided that a man should not join the Army the Military Authorities would not dare to send him... Anyone with the slightest knowledge of human nature must be well aware that to punish a conceited upstart of this type, especially when he is a man of no real influence, like Cook, always gives universal satisfaction." (80)

Cook continued to make speeches against the war. When he visited the village of Ynyshir he called on miners to do what they could to bring the war to an end: "Are we going to allow this war to go on? The government wants a hundred thousand men. They demand fifty thousand immediately, and the Clyde workers would not allow the government to take them. Let us stand by them, and show them that Wales will do the same. I have two brothers in the army who were forced to join, but I say No! I will be shot before I go to fight. Are you going to allow us to be taken to the war? If so, I say there will not be a ton of coal for the navy." (81)

Once again Captain Lionel Lindsay contacted the Home Office: "As promised I enclose a list of the ILP and advanced Syndicalists employed at our collieries, who are really the cause of a good deal of the trouble in this part of the coalfield, not only at our own collieries, but also in the neighbourhood. Of this lot, Cook is by far the most dangerous. As he considers himself an orator he has most to say at the various meetings in the district, and without exception, the policy which he preaches is the down-tool policy, and he is also concerned with the peace-cranks." (82)

In March 1918 the Home Office acceded to Lindsay's pressure and Cook as arrested and charged with sedition, Charged under the Defence of the Realm Act and was found guilty "of making statements likely to cause disaffection to His Majesty among the civilian population" and was sentenced to three months' imprisonment. Miners in the Rhondda threatened strike action and Cook was released after serving only two months. (83)

Coal production fell dramatically between 1916-1918. J. F. Martin, the author of The Government and the Control of the British Coal Industry, 1914-1918 (1981) pointed out: "The decline in the amount of coal extracted per man-shift and the reduction in the number of shifts worked per year were part of a common cause, namely the decline in the physical ability of the male workers in the industry. To a large extent this was an inevitable legacy of the recruitment of large numbers of men in the early stages of war. Most of the miners who enlisted were in fact the youngest and fittest members of the industry. Thus it can be rightly assumed that their removal had a disproportionate effect on the remaining men's ability to produce coal, apart from the fact that the industry lost its highest productivity workers." (84)

The Coal Industry: 1919-1925

Two weeks after the end of the war, the prime minister, David Lloyd George gave a speech in Wolverhampton: "‘The work is not over yet – the work of the nation, the work of the people, the work of those who have sacrificed. Let us work together first. What is our task? To make Britain a fit country for heroes to live in. I am not using the word ‘heroes’ in any spirit of boastfulness, but in the spirit of humble recognition of fact. I cannot think what these men have gone through. I have been there at the door of the furnace and witnessed it, but that is not being in it, and I saw them march into the furnace. There are millions of men who will come back. Let us make this a land fit for such men to live in. There is no time to lose. I want us to take advantage of this new spirit. Don’t let us waste this victory merely in ringing joybells." (85)

However, the government was slow to provide a "country for heroes to live in". After the war the ending of price controls, prices rose twice as fast during 1919 as they had done during the worst years of the war. That year 35 million working days were lost to strikes, and on average every day there were 100,000 workers on strike - this was six times the 1918 rate. There were stoppages in the coal mines, in the printing industry, among transport workers, and the cotton industry. There were also mutinies in the military and two separate police strikes in London and Liverpool. (86)

The miners were encouraged to go back to work by the government agreeing to establish a royal commission under John Sankey, a high court judge. Others on the commission included trade unionists, Robert Smillie, Herbert Smith and Frank Hodges. Other progressive figures such as R. H. Tawney, Sidney Webb and Leo Chiozza Money, were also included, but Arthur Balfour, and several conservative businessmen meant that they could not publish a united report.

In June 1919 the Sankey Commission came up with four reports, which ranged from complete nationalization on the part of the workers' representatives to restoration of undiluted private ownership on that of the owners. On 18th August, Lloyd George used the excuse of this disagreement to reject nationalization but offered the prospect of reorganization. When this was rejected by the Miners' Federation of Great Britain, the government kept control of the industry. It also agreed to pass legislation that would guarantee the miners a seven-hour day. (87)

In January 1921, Arthur J. Cook, the left-wing militant from South Wales became a member of the executive of the Miners' Federation of Great Britain (MFGB). "A month later the decontrol of the mining industry was announced, with a consequent end to a national wages agreement and wage reductions. A three-month lock-out from April 1921 ended in defeat for the miners; at its end Cook was again gaoled for two months' hard labour for incitement and unlawful assembly". (88)

Will Paynter, later recorded: "Cook had been a union leader at the colliery next down the valley to where I worked and we heard much of his exploits there as a fighter for wages and particularly for pit safety... He was... a master of his craft on the platform. I attended many of his meetings when he came to the Rhondda and he was undoubtedly a great orator, and had terrific support throughout the coalfields." (89) During this period he developed a reputation as a great orator. John Sankey, a High Court Judge, once stood at the back of a crowded miners' meeting to hear Cook speak. "Within fifteen minutes half the audience was in tears and Sankey admitted to having the greatest difficulty in restraining himself from weeping." (90)

In 1924 Harry Pollitt was appointed General Secretary of the National Minority Movement, a Communist-led united front within the trade unions. Pollitt worked alongside Tom Mann and according to one document the plan was "not to organize independent revolutionary trade unions, or to split revolutionary elements away from existing organizations affiliated to the T.U.C. but to convert the revolutionary minority within each industry into a revolutionary majority." Cook and a large number of miners also joined this organization. (91)

Newspapers became increasingly concerned about the political activities of Cook. The Daily Mail reported that at a Labour Party meeting he claimed that people such as Jimmy Thomas and Tom Shaw "had no political class consciousness, and that the Labour leaders and trade union leaders were square pegs in round holes. He was glad to find some Red Socialists in London. He hoped he would find more later". The newspaper quoted Cook as saying: "I believe solely and absolutely in Communism. If there is no place for the Communists in the Labour Party, there is no place for the Right Wingers. I believe in strikes. They are the only weapon". (92)

Frank Hodges, general secretary of the Miners' Federation of Great Britain (MFGB) was elected for Litchfield in the 1923 General Election. Under the rules of the union he now had to resign his post but he initially refused. It was not until he was appointed as Civil Lord of the Admiralty in the Labour Government that he agreed to go. However, his time in Parliament did not last long and he was defeated in the 1924 General Election. (93)

Arthur J. Cook went on to secure the official South Wales nomination and subsequently won the national ballot by 217,664 votes to 202,297. Fred Bramley, general secretary of the TUC, was appalled at Cook's election. He commented to his assistant, Walter Citrine: "Have you seen who has been elected secretary of the Miners' Federation? Cook, a raving, tearing Communist. Now the miners are in for a bad time." However, his victory was welcomed by Arthur Horner who argued that Cook represented “a time for new ideas - an agitator, a man with a sense of adventure”. (94)

Red Friday

On 30th June 1925 the mine-owners announced that they intended to reduce the miner's wages. Will Paynter later commented: "The coal owners gave notice of their intention to end the wage agreement then operating, bad though it was, and proposed further wage reductions, the abolition of the minimum wage principle, shorter hours and a reversion to district agreements from the then existing national agreements. This was, without question, a monstrous package attack, and was seen as a further attempt to lower the position not only of miners but of all industrial workers." (95)

On 23rd July, 1925, Ernest Bevin, the general secretary of the Transport & General Workers Union (TGWU), moved a resolution at a conference of transport workers pledging full support to the miners and full co-operation with the General Council in carrying out any measures they might decide to take. A few days later the railway unions also pledged their support and set up a joint committee with the transport workers to prepare for the embargo on the movement of coal which the General Council had ordered in the event of a lock-out." (96) It has been claimed that the railwaymen believed "that a successful attack on the miners would be followed by another on them." (97)

In an attempt to avoid a General Strike, the prime minister, Stanley Baldwin, invited the leaders of the miners and the mine owners to Downing Street on 29th July. The miners kept firm on what became their slogan: "Not a minute on the day, not a penny off the pay". Herbert Smith, the president of the National Union of Mineworkers, told Baldwin: "We have now to give". Baldwin insisted there would be no subsidy: "All the workers of this country have got to take reductions in wages to help put industry on its feet." (98)

The following day the General Council of the Trade Union Congress triggered a national embargo on coal movements. On 31st July, the government capitulated. It announced an inquiry into the scope and methods of reorganization of the industry, and Baldwin offered a subsidy that would meet the difference between the owners' and the miners' positions on pay until the new Commission reported. The subsidy would end on 1st May 1926. Until then, the lockout notices and the strike were suspended. This event became known as Red Friday because it was seen as a victory for working class solidarity. (99)

Primary Sources

(1) Edward Davies, a doctor at Cyfarthfa was interviewed by a Parliamentary Commission in 1841.

The average duration of a collier's life is considerably less than of other workmen... because of the frequency of fatal accidents... As age advances, they suffer from chronic bronchial problems.

(2) James Brown, a doctor from Pembrokeshire, was interviewed by a Parliamentary Commission in 1841.

The average life of a collier is about forty; they rarely reach forty-five years of age... The entire population of Begelly and East Williamson is 1,463... Of this mining population, there are not six colliers of sixty years of age.

(3) Sarah Gooder, aged eight, was interviewed by the Children's Employment Commission Report (1842)

I'm a trapper in the Gawber pit. It does not tire me, but I have to trap without a light and I'm scared. I go at four and sometimes half past three in the morning, and come out at five and half past. I never go to sleep. Sometimes I sing when I've light, but not in the dark; I dare not sing then. I don't like being in the pit. I am very sleepy when I go sometimes in the morning. I go to Sunday-schools and read Reading made Easy.... They teach me to pray... I have heard tell of Jesus many a time. I don't know why he came on earth, I'm sure, and I don't know why he died, but he had stones for his head to rest on. I would like to be at school far better than in the pit.

(4) Rosa Lucas, aged seventeen, Lamberhead Green Colliery (19th May, 1841)

Q: You are a drawer, I believe, when at work?

A: Yes, I am.

Q: Where do you work?

A: At Mr. Morris's. I used to work at Blundell's.

Q: What age were you when you first began to work in the pits?

A: I was about 11 I think.

Q: Do you work at night in Morris's pits?

A: Yes, when I was able to work. I worked one week in the day time and the next at night, the same as the drawers did.

Q: Are there any children in the pit where you work?

A: Oh, yes, both little employed in the pits.and big some not older or bigger than him (pointing to a little boy of six or seven years old); they put them to tenting air-doors.

Q: What hours do you work?

A: I go down between three and four in the morning and sometimes I have done by five o'clock in the afternoon, and sometimes sooner.

Q: Have you any fixed hour for dinner?

A: Yes, we have an hour for dinner dinner during the day.in the day-time, but we don't stop at night.

Q: When you are working the night-turn, what hours do you work?

A: I go at night at two o'clock in the afternoon, and sometimes three. I come up it will be about three o'clock in the morning, and sometimes before.

Q: You have no regular times for meals at night?

A: No, we never stop at during the night.

Q: Do you find the work very hard?

A: Yes, it is very hard work for a woman. from over work.I have been so tired many a time that I could scarcely wash myself. I was obliged to leave Mr. Blundell's pit, it was so hot... I could scarcely ever wash myself at night, I was so tired; and I felt very dull and stiff when I set off in the morning.

Q: Have you ever had many accidents besides the one you are now suffering from?

A: Yes, I had once a great big hole in my other leg. I thought it was the water that did it, for I was working in a wet place then.

Q: Are Mr. Morris's pits dry?

A: Yes, very dry.

Q: How did the accident happen you are now suffering from?

A: I was sitting on the edge of a tub at the bottom, and a great stone fell from the roof on my foot and ankle, and crushed it to pieces, and it was obliged to be taken off.

Q: Have you ever seen the drawers beaten?

A: Yes, some gets beaten. Mary inflicted on drawers. Tuity gets beaten nearly every day.

Q: What do they beat her with?

A: A pick-arm.

Q: What do they beat her for?

A: I suppose it is for 'sauce;' she has a very saucy tongue.

Q: What age is she?

A: She is 23 years old.

Q: What is your father?

A: He was a collier, but he was killed in a coal-pit. I go past the place where he was killed many a time when I am working, and sometimes I think I see something.

(5) The testimony of Ann Eggley, aged 18, appeared in The Physical and Moral Condition of the Children and Young Persons employed in Mines and Manufactures (1843)

We go at four in the morning, and sometimes at half-past four. We begin to work as soon as we get down. We get out after four, sometimes at five, in the evening. We work the whole time except an hour for dinner, and sometimes we haven't time to eat. I hurry by myself, and have done so for long. I know the corves are very heavy they are the biggest corves anywhere about. The work is far too hard for me; the sweat runs off me all over sometimes. I am very tired at night. Sometimes when we get home at night we have not power to wash us, and then we go to bed. Sometimes we fall asleep in the chair. Father said last night it was both a shame and disgrace for girls to work as we do, but there was nought else for us to do. I have tried to get winding to do, but could not. I begun to hurry when I was seven and I have been hurrying ever since. I have been 11 years in the pit.

The girls are always tired. I was poorly twice this winter; it was with headache. I hurry for Robert Wiggins; he is not akin to me. I riddle for him. We all riddle for them except the littlest when there is two. We don't always get enough to eat and drink, but we get a good supper. I have known my father go at two in the morning to work when we worked at Twibell's, where there is a day-hole to the pit, and he didn't come out till four. I am quite sure that we work constantly 12 hours except on Saturdays. We wear trousers and our shifts in the pit, and great big shoes clinkered and nailed.

The girls never work naked to the waist in our pit. The men don't insult us in the pit. The conduct of the girls in the pit is good enough sometimes and sometimes bad enough. I never went to a day-school. I went a little to a Sunday-school, but I soon gave it over. I thought it too bad to be confined both Sundays and weekdays. I walk about and get the fresh air on Sundays. I have not learnt to read. I don't know my letters. I have never learnt nought. I never go to church or chapel; there is no church or chapel at Gawber, there is none nearer than a mile. If I was married I would not go to the pits, but I know some married women that do. The men do not insult the girls with us, but I think they do in some. I have never heard that a good man came into the world who was God's Son to save sinners. I never heard of Christ at all. Nobody has ever told me about him, nor have my father and mother ever taught me to pray. I know no prayer; I never pray. I have been taught nothing about such things.

(6) The testimony of Betty Harris, aged 37, appeared in The Physical and Moral Condition of the Children and Young Persons employed in Mines and Manufactures (1843)

I was married at 23 and went into a colliery when I was married. I used to weave when about 12 years old, and can neither read nor write. I work to Andrew Knowles, of Little Bolton, and make sometimes about 7s. a week, sometimes not so much. I am a drawer, and work from six o'clock in the morning to six at night. stop about an hour at noon to eat my dinner: I have bread and butter for dinner; I get no drink. I have two children, but they are too young to work. I worked at drawing when I was in the family way. I know a woman who has gone home and washed herself, taken to her bed, been delivered of a child, and gone to work again under a week. I have a belt round my waist, and a chain passing between my legs, and I go on my hands and feet. The road is very steep, and we have to hold the rope; and, where there is no rope, by anything we can catch hold of. There are six women and about six boys and girls in the pit I work in; it is very hard work for a woman. The pit is very wet where I work, and the water comes over the clog-tops always, and I have seen it up to my thighs: it rains in at the roof terribly; my clothes were wet through almost all day long. I never was ill in my life but when I was lying-in. My cousin looks after the children in the day-time, I am very tired when I get home at night; I fall asleep sometimes before I get washed. I am not so strong as I was, and cannot stand my work so well as I used to do. I have drawn till I have had the skin off me: the belt and chain is worse when we are in the family way. My feller [husband] has beaten me many a time for not being ready. I were not used to it at first, and he had little patience: I have known many a man beat his drawer. I have known men take liberties with the drawers, and some of the women have bastards. I think it would be better if we were paid once a week instead of once a month, for then I would buy victuals with ready money. It is bad to live on 7s., and rent 1s. 6d.

I have been hurt once: I got on a waggon of coals in the pit to get out of the way of the next waggon, and the waggon I was on went off before I could get off, and crushed my bones about the hips between the roof and the coals: I was ill 23 weeks. Mr. Fitzgerald and Mr. Fletcher will not have Mr. women in the pits. I have heard of knocks or joults: I had my arm broken by a waggon; I had gotten all out of the road by my arm. and it broke my arm.

The women are frequently wicked, and swear dreadfully at the bottom of the pit at each other, about their turn to hook-on. They are like to stand up for themselves; keeping one from hooking-on is like taking the meat out of one's mouth. There are some women that go to church regularly, and some that does not. Women with a family can seldom go to church. Some have a mother to look after. Collier's houses are generally ill off for furniture. I have a table and a bed, and I have a tin kettle to boil potatoes in. I wear a pair of trousers and a jacket, and am very hot when working, but cold when standing still. They beat the children badly; if they are very little they get beat. There is a great deal on managing a house; some can manage better than others; those that can write and have been properly taught can manage best. My husband can read and write.

(7) Betty Wardle, Children's Employment Commission Report (1842)

Q: Have you ever worked in a coal pit?

A: Ay, I have worked in a pit since I was six years old.

Q: Have you any children?

A: Yes, I have four children; two of them were born while I worked in the pits.

Q: Did you work in the pits whilst you were in the family way?

A: Ay, to be sure. I had a child born in the pits, and I brought it up the pit-shaft in my skirt.

Q: Are you quite sure you are telling the truth?

A: Ay, that I am; it was born the day after I was married, that makes me to know.

Q: Did you draw with the belt and chain?

A: Yes, I did.

(8) Thomas Wilson, owner of three collieries in the area of Silkstone, interviewed by Parliamentary Commission (1841)

The employment of females of any age in and about the mines is most objectionable, and I should rejoice to see it put an end to; but in the present feeling of the colliers, no individual would succeed in stopping it in a neighbourhood where it prevailed, because the men would immediately go to those pits where their daughters would be employed.

The only way effectually to put an end to this and other evils in the present colliery system is to elevate the minds of the men; and the only means to attain this is to combine sound moral and religious training and industrial habits with a system of intellectual culture much more perfect than can at present be obtained by them.

I object on general principles to government interference in the conduct of any trade, and I am satisfied that in mines it would be productive of the greatest injury and injustice. The art of mining is not so perfectly understood as to admit of the way in which a colliery shall be conducted being dictated by any person, however experienced, with such certainty as would warrant an interference with the management of private business. I should also most decidedly object to placing collieries under the present provisions of the Factory Act with respect to the education of children employed therein.

First, because, if it is contended that coal-owners, as employers of children, are bound to attend to their education, this obligation extends equally to all other employers, and therefore it is unjust to single out one class only; secondly, because, if the legislature asserts a right to interfere to secure education, it is bound to make that interference general; and thirdly, because the mining population is in this neighbourhood so intermixed with other classes, and is in such small bodies in any one place, that it would be impossible to provide separate schools for them.

(9) Isabel Wilson, 38 years old, Children's Employment Commission Report (1842)

When women have children... they are compelled to take them down early. I have been married 19 years and have had 10 bairns (children); seven are in life. I was a carrier of coals, which caused me to miscarry five times from the strains, and was ill after each. My last child was born on Saturday morning, and I was at work on the Friday night.

Once met with an accident; a coal brake my cheek-bone, which kept me idle some weeks.

None of the children read, as the work is no regular. I did read once, but no able to attend to it now; when I go below lassie 10 years of age keeps house and makes the broth or stir-about.

(10) Isabel Hogg, aged 53, Children's Employment Commission Report (1842)

I have been married 37 years; it was the practice to marry early, when the coals were all carried on women's backs, men needed us; from the great sore labour false births are frequent and very dangerous.

I have four daughters married, and all work below till they bear their bairns (children) - one is very badly now from working while pregnant, which brought on a miscarriage from which she is not expected to recover.

Collier-people suffer much more than others - my good man died nine years since with bad breath; he lingered some years and was entirely off work 11 years before he died.

You must just tell the Queen Victoria that we are good loyal subjects; women-people here don't mind work, but they object to horse-work; and that she would have the blessings of all the Scotch coal-women if she would get them out of the pits, and send them to other labour.

(11) Children's Employment Commission Report (1842)

The chief miners, the undergoers, were lying on their sides, and with their picks were clearing away the coal to a height of a little more than two feet. Boys were employed in clearing out what the men had disengaged... Children were chained, belted, harnessed like dogs in a go-cart, black, saturated with wet, and more than half-naked - crawling upon their hands and feet, and dragging their heavy loads behind them - they present an appearance indescribably disgusting and unnatural.

(12) Alexander Macdonald, evidence before the Royal Commission on Trade Unions (28th April, 1868)

I entered the mines at about eight years of age. The condition of the miner's boy then was to be raised about 1 o'clock or 2 o'clock in the morning if the distance was very far to travel, and at that time I had to travel a considerable distance, more than three miles. We remained at the mine until 5 and 6 at night. It was an ironstone mine, very low, working about 18 inches, and in some instances not quite so high. Then I moved to coal mines. There we had low seams also, very low seams. There was no rails to draw upon, that is, tramways. We had leather belts for our shoulders. We had to keep dragging the coal with these ropes over our shoulders, sometimes round the middle with a chain between our legs. Then there was always another behind pushing with his head...

That work was done by boys, such as I was, from 10 to 11 down to eight, and I have known them as low as seven years old. In the mines at that time the state of ventilation was frightful... It did not lead to frequent accidents; but it lead to premature death... There was no explosive gas in those mines I was in, or scarcely any. I may state incidentally here that in the first ironstone mine I was in there were some 20 or more boys besides myself, and I am not aware at this moment that there is one alive excepting myself.

Student Activities

The Coal Industry: 1600-1925 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the Coalmines (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour in the Collieries (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)