On this day on 18th November

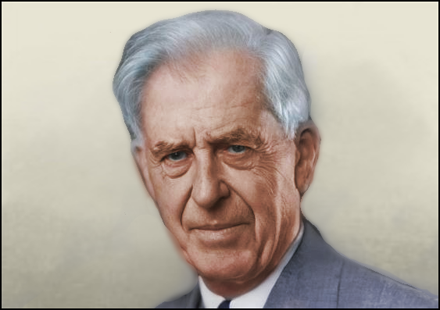

On this day in 1901 George Gallup was born. Gallup's mother-in-law was active in the Democratic Party and in 1932 he carried out a political survey to discover her chances of being elected secretary of state for Iowa. In 1935 he formed his own polling company, the American Institute of Public Opinion. Gallup later explained: "The American Institute of Public Opinion, a non-partisan fact-finding organization which will report the trend of public opinion on one major issue each week". According to Michael Wheeler, the author of Lies, Damn Lies, and Statistics: The Manipulation of Public Opinion in America (2007): "Gallup did not start polling professionally until 1935, but everything he did before then, the journalism and the advertising in particular, had a strong influence on his orientation as a pollster. Much of Gallup's success is attributable to his understanding of what sells newspapers, as well as his own gift for self-promotion. When Gallup began, there were no pollsters as such. He did not pursue a career; rather, he created one."

Gallup's first survey, carried out in October, 1935, concerned the policies of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Gallup argued that he collected this information "by means of personal interviews and mail questionnaires from thousands of voters located in every state in the union... persons in all walks of life have been polled in order to obtain an accurate cross section." Gallup's first poll showed that 60% of those questioned thought that the government was spending too much money on "relief and recovery". A second survey showed that Roosevelt's support had declined dramatically since the 1932 Presidential Election. These poll results were published in leading newspapers.

The 1936 Presidential Election was the first where polls were published in newspapers during the campaign. The Literary Digest sent out 10,000,000 questionnaires to voters. Gallup used a very different strategy: "The sampling procedure described is designed to produce an approximation of the adult civilian population living in the United States, except for the persons in institutions such as prisons or hospitals... The places (where people were interviewed) were selected to provide broad geographic distribution within states and at the same time in combination to be politically representative of the state or group of states in terms of three previous elections."

The Literary Digest predicted that Alfred Landon (57%) would defeat Roosevelt (43%). Gallup's survey showed Roosevelt winning with 55.7% of the vote. Although this was 4% less than Roosevelt actually achieved, Gallup's more scientific method was deemed to be a success. It later emerged the magazine reported its results based on only 15% of the questionnaires set out. It seems that Landon's supporters were much more willing to send back their questionnaires and therefore distorting the results.

Gallup was a member of the Republican Party and he was accused of under-reporting Roosevelt's support in order to influence the final result. Gallup defended himself by arguing that "we pride ourselves on being fact-finders and scorekeepers, nothing else." To demonstrate his neutrality he said that he never voted in elections where he had carried out surveys: "It would be as if the referee at the next Princeton-Yale game announced loudly that he was in favour of Princeton. Everything he would do would be a little suspect."

In 1939 Gallup employed David Ogilvy to work for the Audience Research Institute. Ogilvy later claimed that it was the luckiest break of his life "as it furnished him with immeasurably useful knowledge about the techniques of marketing research, as well as about what made United States citizens really tick". The following year Ogilvy was recruited as an agent by William Stephenson, the head of the British Security Coordination (BSC). As William Boyd has pointed out: "The phrase (British Security Coordination) is bland, almost defiantly ordinary, depicting perhaps some sub-committee of a minor department in a lowly Whitehall ministry. In fact BSC, as it was generally known, represented one of the largest covert operations in British spying history... With the US alongside Britain, Hitler would be defeated - eventually. Without the US (Russia was neutral at the time), the future looked unbearably bleak... polls in the US still showed that 80% of Americans were against joining the war in Europe. Anglophobia was widespread and the US Congress was violently opposed to any form of intervention." An office was opened in the Rockefeller Centre in Manhattan with the agreement of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and J. Edgar Hoover of the FBI.

One of Ogilvy's tasks was to persuade Gallup from publishing polls considered harmful to the British. As Richard W. Steele has pointed out: "public opinion polls had become a political weapon that could be used to inform the views of the doubtful, weaken the commitment of opponents, and strengthen the conviction of supporters." William Stephenson later admitted: "Great care was taken beforehand to make certain the poll results would turn out as desired. The questions were to steer opinion toward the support of Britain and the war... Public Opinion was manipulated through what seemed an objective poll." According to Thomas E. Mahl, the author of Desperate Deception: British Covert Operations in the United States, 1939-44 (1998): "BSC persuaded Gallup... to drop the results of questions that reflected poorly on the British cause."

Michael Wheeler, the author of Lies, Damn Lies, and Statistics: The Manipulation of Public Opinion in America (2007) has argued: "Proving that a given poll is rigged is difficult because there are so many subtle ways to fake data... a clever pollster can just as easily favor one candidate or the other by making less conspicuous adjustments, such as allocating the undecided voters as suits his needs, throwing out certain interviews on the grounds that they were non-voters, or manipulating the sequence and context within which the questions are asked... Polls can even be rigged without the pollster knowing it.... Most major polling organizations keep their sampling lists under lock and key."

David Ogilvy worked closely with Hadley Cantril, who was secretly working for President Franklin D. Roosevelt. In a secret report written by a team of BSC agents that included Roald Dahl and H. Montgomery Hyde, pointed out: "As the campaign against Fifth Columnists in the US continued, BSC was able, through the Gallup Poll, to see how its progress was affecting American public opinion. The results, as polled by Gallup, were most gratifying. On 11 March, only 49% of the American people thought that Britain was doing her utmost to win the war. On 23 April, this proportion had jumped to 65%, although no important naval or military victory had occurred during this period to influence the public in Britain's favour. Gallup's assistant (Ogilvy), who eventually joined the staff of BSC, was able to ensure a constant flow of intelligence on public opinion in the United States, since he had access not only to the questionnaires sent out by Gallup and Cantril and to the recommendations offered by the latter to the White House, but also to the findings of the Survey Division of the Office of War Information and of the Opinion Research Division of the US Army."

Gallup was a close friend of Thomas Dewey and tried very hard to make him the Republican Party candidate in the 1944 Presidential Election. The British Security Coordination secret report claimed that the "Gallup Poll did not prove a reliable guide to the Presidential election of 1944. This was so, largely because Gallup is himself a Republican and a staunch supporter of Dewey. As William Stephenson learned, there was little doubt that Gallup deliberately adjusted his figures in Dewey's favour in the hope of stampeding the electorate." Ernest Cuneo told Stephenson: "Dewey is one of Gallup's principal clients... Dewey is calling up Gallup so often they have to have a clerk to answer him."

Gallup was also accused of trying to get Thomas Dewey elected against Harry S. Truman in the 1948 Presidential Election. Truman lost all nine of the Gallup Poll's post-election surveys. In late September, Dewey had a 17 point lead. According to Albert E. Sindlinger, who worked for Gallup, claimed that "before the 1948 election Dewey and Gallup were on the phone constantly. Dewey was looking for a handle on public opinion and he turned to George Gallup." Sindlinger says Gallup deliberately rigged the polls to favour Dewey. "Gallup's sample excluded people who hadn't voted before. I found that they were heavily pro-Truman, but Gallup just didn't count them." Sindlinger added: "We'd set up the headlines and draft the story, and then we would go out and do the surveys to fill in the gaps. If the results squared with our story, we'd congratulate ourselves on how smart we were. But if they didn't, then the data would be adjusted, supposedly because there was something wrong with the sample."

Gallup was severely embarrassed by Truman winning with 49.6%of the vote compared to 45.1% for Dewey. Sindlinger believes that Gallup's biased polls helped to defeat Dewey as it made the Republicans over-confident. Sindlinger admits that during the campaign he came across a lot of people who said they would not bother to vote because Dewey was a certainty: "pollsters may deny it, but if you look at the evidence it's overwhelmingly clear that polls do influence people."

A number of his subscribing newspapers threatened to cancel their contracts because Gallup's polls did not reflect the result. Gallup replied that scientific surveys be expected to take into account "bribery of voters" and "tampering with ballot boxes"? By 1950 Gallup's market research business picked up. Gallup later explained: "The fact that the polls would recover was in my mind absolutely inevitable. The one thing that sustained me was the fact that no one had ever found a better system for understanding public opinion and I didn't think anyone ever would."

On this day in 1906 Klaus Mann, the son of the novelist, Thomas Mann, was born in Munich. His sister, Erika Mann, had been born the previous year. With a group of friends, Erika and Klaus, they founded an experimental theater troupe, the Laienbund Deutscher Mimiker. In 1924 Klaus wrote Anja and Esther, a play about "a neurotic quartet of four boys and girls" who "were madly in love with each other". The following year he was approached by the actor Gustaf Gründgens, who wanted to direct the play with himself in one of the male roles, Klaus in the other; Erika Mann and Pamela Wedekind, the daughter of the playwright Frank Wedekind, would be the two young women. "Klaus planned to marry Pamela, with whom Erika fell in love, while Erika arranged to marry Gustaf, with whom Klaus began an affair."

The play, which opened in Hamburg in October 1925, attracted vast amounts of publicity, partly because of its scandalous content and partly because it starred three children of two famous writers. A photograph appeared on the cover of Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung. It created a great deal of controversy as "Klaus's lipstick gave him the look of a transvestite".

In 1932 Klaus and Erika Mann joined together with a group of left-wing activists, including Therese Giehse, Walter Mehring, Magnus Henning, Wolfgang Koeppen and Lotte Goslar, to establish a cabaret in Munich called Die Pfeffermühle (The Peppermill).

The production opened on 1st January, 1933. Klaus and Erika wrote most of the material, much of which was anti-Fascist. It ran for two months next door to the local Nazi headquarters, and, since it was so successful, was preparing to move to a larger theatre when the Reichstag went up in flames. Erika and Klaus were on a skiing holiday while the new theatre was being decorated and arrived back in Munich to be warned by the family chauffeur, that they were in danger. Later, Klaus wrote that the chauffeur "had been a Nazi spy throughout the four or five years he lived with us... But this time he had failed in his duty, out of sympathy, I suppose. For he knew what would happen to us if he informed his Nazi employers of our arrival in town."

Adolf Hitler gained power in January 1933. Soon afterwards, a large number of writers were declared to be "degenerate authors". This included Heinrich Mann, Bertolt Brecht, Hans Eisler, Ernst Toller, Thomas Heine, Arnold Zweig, Ludwig Renn, Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud, Franz Kafka and Hermann Hesse. On 10th May, the Nazi Party arranged the burning of thousands of "degenerate literary works" were burnt in German cities.

Thomas Mann was on holiday in France when Hitler took power. Erika and Klaus were warned by the family chauffeur that the Mann family were in danger. (19) Later, Klaus wrote that the chauffeur "had been a Nazi spy throughout the four or five years he lived with us... But this time he had failed in his duty, out of sympathy, I suppose. For he knew what would happen to us if he informed his Nazi employers of our arrival in town."

Erika made contact with her parents, and warned them not to return to Munich. Mann, who was on holiday at the time, was warned that he faced the possibility of being arrested if he returned to Germany. In September, 1933, Thomas, Katia, Gottfried, Monika, Elisabeth and Michael Mann settled in Küsnacht, near Zurich. Erika and Klaus decided to remain in Germany to continue the fight against fascism.

Klaus Mann went to live in Amsterdam, where he worked for the first emigre journal of anti-fascism, Die Sammlung, which attacked Adolf Hitler and his government in Nazi Germany. His father's brother, Heinrich Mann, also contributed to the magazine. Thomas Mann condemned the venture and pleaded with his son and brother to withdraw their support for the journal.

Klaus returned with his parents to the US and sought citizenship only to find that he was once more under investigation by the FBI. So were his friends such as Hans Eisler and Bertolt Brecht were ordered to appear before the Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Eisler and Brecht both decided to leave the country. Mann described the behaviour of members of the HUAC such as John Rankin and J. Parnell Thomas as "fascistic". In his diary he wrote: "What oath would Congressman Rankin or Thomas take if forced to swear that they hated fascism as much as Communism?"

Klaus Mann made several attempts to kill himself. While in Los Angeles in 1948 he attempted suicide by slitting his wrists, taking pills and turning on the gas. Thomas Mann wrote to a friend: "My two sisters committed suicide, and Klaus has much of the elder sister in him. The impulse is present in him, and all the circumstances favour it – the one exception being that he has a parental home on which he can always rely."

At the beginning of January 1949, Klaus Mann wrote in his diary: "I do not wish to survive this year." In April, in Cannes, he received a letter from a West German publisher to say that his novel, Mephisto, could not be published in the country because of the objections of Gustaf Gründgens (the book is a thinly-disguised portrait of Gründgens, who abandoned his conscience to ingratiate himself with the Nazi Party).

Klaus wrote to Erika about his problems with his publisher and his financial difficulties. "I have been luck with my family. One cannot be entirely lonely if one belongs to something and is part of it." Klaus Mann died in of an overdose of sleeping pills on 21st May 1949.

Klaus Mann (c. 1932)

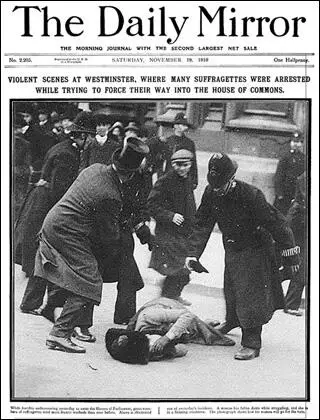

On this day 1910, Emmeline Pankhurst, led 300 women in a protest against the defeat of the Conciliation Bill. In January 1910, H. H. Asquith called a general election in order to obtain a new mandate. However, the Liberals lost votes and was forced to rely on the support of the 42 Labour Party MPs to govern. Henry Brailsford, a member of the Men's League For Women's Suffrage wrote to Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the National Union of Woman's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), suggesting that he should attempt to establish a Conciliation Committee for Women's Suffrage. "My idea is that it should undertake the necessary diplomatic work of promoting an early settlement".

Emmeline Pankhurst, the leader of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) agreed to the idea and they declared a truce in which all militant activities would cease until the fate of the Conciliation Bill was clear. A Conciliation Committee, composed of 36 MPs (25 Liberals, 17 Conservatives, 6 Labour and 6 Irish Nationalists) all in favour of some sort of women's enfranchisement, was formed and drafted a Bill which would have enfranchised only a million women but which would, they hoped, gain the support of all but the most dedicated anti-suffragists. Fawcett wrote that "personally many suffragists would prefer a less restricted measure, but the immense importance and gain to our movement is getting the most effective of all the existing franchises thrown upon to woman cannot be exaggerated."

The Conciliation Bill was designed to conciliate the suffragist movement by giving a limited number of women the vote, according to their property holdings and marital status. After a two-day debate in July 1910, the Conciliation Bill was carried by 109 votes and it was agreed to send it away to be amended by a House of Commons committee. Asquith made a speech where he made it clear that he intended to shelve the Conciliation Bill.

On hearing the news, Emmeline Pankhurst, led 300 women from a pre-arranged meeting at the Caxton Hall to the House of Commons on 18th November, 1910. Sylvia Pankhurst was one of the women who took part in the protest and experienced the violent way the police dealt with the women: "I saw Ada Wright knocked down a dozen times in succession. A tall man with a silk hat fought to protect her as she lay on the ground, but a group of policemen thrust him away, seized her again, hurled her into the crowd and felled her again as she turned. Later I saw her lying against the wall of the House of Lords, with a group of anxious women kneeling round her. Two girls with linked arms were being dragged about by two uniformed policemen. One of a group of officers in plain clothes ran up and kicked one of the girls, whilst the others laughed and jeered at her."

Henry Brailsford was commissioned to write a report on the way that the police dealt with the demonstration. He took testimony from a large number of women, including Mary Frances Earl: "In the struggle the police were most brutal and indecent. They deliberately tore my undergarments, using the most foul language - such language as I could not repeat. They seized me by the hair and forced me up the steps on my knees, refusing to allow me to regain my footing... The police, I understand, were brought specially from Whitechapel."

Paul Foot, the author of The Vote (2005) has pointed out, Brailsford and his committee obtained "enough irrefutable testimony not just of brutality by the police but also of indecent assault - now becoming a common practice among police officers - to shock many newspaper editors, and the report was published widely". However, Edward Henry, the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, claimed that the sexual assaults were committed by members of the public: "Amongst this crowd were many undesirable and reckless persons quite capable of indulging in gross conduct."

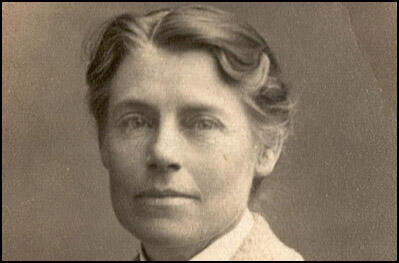

On this day in 1910 suffragette Evelina Haverfield is charged with assaulting a policeman. Haverfield was an early member of the National Union of Suffrage Societies she joined the Women's Social and Political Union in March 1908. She later explained that she joined the WSPU after hearing Minnie Baldock speak at a public meeting. Sylvia Pankhurst recalled: "When she first joined the Suffragette movement her expression was cold and proud... I was repelled when she told me she felt no affection for her children."

In 1909 Haverfield joined Annie Kenney, Mary Blathwayt and Elsie Howey to organise the women's suffrage campaign in the West Country. During this period she became honorary secretary of the Sherborne branch of the WSPU. She retained her membership of the NUWSS and in June 1909 took part in its caravan campaign with Isabella Ford and Ray Strachey.

On 29th June 1909 she was arrested with Emmeline Pankhurst during a demonstration outside the House of Commons. Although she was defended in court by Lord Robert Cecil she was found guilty and fined. The case went to appeal but was dismissed in December and the fine was upheld.

Evelina Haverfield, along with Vera Holme and Maud Joachim, was a mounted marshal for a WSPU procession on 22nd July 1910. On 18th November 1910, she was charged with assaulting a policeman by hitting him in the mouth. In court it was reported that Haverfield had said during the assault that she had not hit him hard enough and that "next time I will bring a revolver." She was sentenced to a fine or a month's imprisonment. She did not go to prison as her fine was paid without her consent. Three days later she was arrested for trying to break through a police cordon outside the House of Commons. This time she was sent to Holloway Prison for two weeks.

On this day 1915, Walter Tull arrives in France. On the outbreak of the First World War Tull immediately abandoned his football career and offered his services to the British Army. On 21st December, 1914, Tull became the first Northampton Town player to join the Football Battalion (17th Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment). At the time it was commanded by Major Frank Buckley.

The Army soon recognized Tull's leadership qualities and he was quickly promoted to the rank of sergeant. Tull arrived in France on 18th November 1915. He was initially billeted at Les Ciseaux, 16 miles from the front line. He had still not seen action when he wrote a letter to Edward Tull-Warnock in January 1916: "For the last three weeks my Battalion has been resting some miles distant from the firing line but we are now going up to the trenches for a month or so. Afterwards we shall begin to think about coming home on leave. It is a very monotonous life out here when one is supposed to be resting and most of the boys prefer the excitement of the trenches."

Walter Tull had impressed his senior officers and recommended that he should be considered for further promotion. Despite military regulations forbidding "any negro or person of colour" being an officer, Tull received his commission in May, 1917. Tull therefore became the first Black combat officer in the British Army. As Phil Vasili has pointed out in his book, Colouring Over the White Line: "According to The Manual of Military Law, Black soldiers of any rank were not desirable. During the First World War, military chiefs of staff, with government approval, argued that White soldiers would not accept orders issued by men of colour and on no account should Black soldiers serve on the front line."

Lieutenant Walter Tull was sent to the Italian front. This was an historic occasion because Tull was the first ever black officer in the British Army. He led his men at the Battle of Piave and was mentioned in dispatches for his "gallantry and coolness" under fire. "You were one of the first to cross the river Piave prior to the raid on 1st-2nd January, 1918, and during the raid you took the covering party of the main body across and brought them back without a casualty in spite of heavy fire."

Tull stayed in Italy until 1918 when he was transferred to France to take part in the attempt to break through the German lines on the Western Front. On 25th March, 1918, 2nd Lieutenant Tull was ordered to lead his men on an attack on the German trenches at Favreuil. Soon after entering No Mans Land Tull was hit by a German bullet. Tull was such a popular officer that several of his men made valiant efforts under heavy fire from German machine-guns to bring him back to the British trenches. These efforts were in vain as Tull had died soon after being hit. One of the soldiers who tried to rescue him later told his commanding officer that Tull was "killed instantaneously with a bullet through his head."

Tull's body was never found. On 17th April 1918, Lieutenant Pickard wrote to Walter's brother and said: "Being at present in command (the captain was wounded) - allow me to say how popular he was throughout the Battalion. He was brave and conscientious; he had been recommended for the Military Cross, and had certainly earned it, the Commanding Officer had every confidence in him, and he was liked by the men. Now he has paid the supreme sacrifice; the Battalion and Company have lost a faithful officer; personally I have lost a friend. Can I say more, except that I hope that those who remain may be true and faithful as he."

On this day in 1919 Andrée Borrel was born in France. The daughter of working-class parents, she grew up on the outskirts of Paris. At fourteen she left school to become a dressmaker. In 1933 she moved to Paris where she found work as a shop assistant in a bakery, the Boulangerie Pujo. Two years later she moved to a shop called the Bazar d'Amsterdam.

On the outbreak of the Second World War Borrel moved with her mother to Toulon on the Mediterranean coast. After training with the Red Cross she joined the Association des Dames de France and worked in Beaucaire treating wounded soldiers of the French Army.

After France surrendered Borrel and her friend, Maurice Dufour, joined the French Resistance. They established a villa outside Perpignan close to the Spanish border. Over the next six months they joined the network led by Albert Guérisse, that helped British airman shot down over France to escape back to Britain.

In December 1940 the network was betrayed Borrel and Dufour were forced to abandon the villa and hid in Toulouse. Eventually they escaped to Portugal where Borrel went to work at the Free French Propaganda Office at the British Embassy in Lisbon. Borrel stayed in Portugal until April 1942 when she travelled to London.

On her arrival Borrel was taken to the Royal Patriotic School where she was interrogated in case she was a double agent. Although she was known to have strong socialist views she was recruited by the Special Operations Executive (SOE) as a British special agent.

Given the code name "Denise", Andrée Borrel and Lise de Baissac, became the first women agents to be was parachuted into France on 24th September 1942. They landed in the village of Boisrenard close to the town of Mer. After staying with the French Resistance for a couple of days Baissac moved to Poiters to start a new network whereas Borrel went to Paris to join the new Prosper Network that was to be led by Francis Suttill and included Jack Agazarian and Gilbert Norman.

Suttill was impressed with Borrel and despite her young age in March 1943 became second in command of the network. He told the Special Operations Executive in London that she "has a perfect understanding of security and an imperturbable calmness." He added: "Thank you very much for having sent her to me."

On 23rd June, 1943, the three key members of the Prosper Network, Andrée Borrel, Francis Suttill and Gilbert Norman, were arrested. Borrel was taken to Avenue Foch, the Gestapo headquarters, in Paris. After being interrogated she was sent to Fresnes Prison.

On 13th May 1944 the Germans transported Borrel and seven other SOE agents, Vera Leigh, Diana Rowden, Sonya Olschanezky, Yolande Beekman, Eliane Plewman, Odette Sansom and Madeleine Damerment to Nazi Germany.

On 6th July 1944, Borrel along with Vera Leigh, Diana Rowden and Sonya Olschanezky, were taken to the Concentration Camp at Natzweiler. Later that day they were injected with phenol and put in the crematorium furnace.

On this day 1938, Vernon Bartlett, the anti-appeasement candidate won the -seat of Bridgwater. Bartlett worked as a journalist for the Daily Chronicle and Picture Post. He wrote about Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany and warned against the appeasement policy of Neville Chamberlain and the Conservative government. Bartlett was a harsh critic of the Munich Agreement and afterwards was approached by Richard Acland to stand as an anti-Chamberlain candidate at a by-election in Bridgwater. Bartlett agreed and surprisingly won the previously safe Tory seat and became a member of the House of Commons.

Bartlett was a founder member of the 1941 Committee. Other members included Edward G. Hulton, J. B. Priestley, Kingsley Martin, Richard Acland, Michael Foot, Tom Winteringham, Violet Bonham Carter, Konni Zilliacus, Victor Gollancz, Storm Jameson and David Low. In December 1941 the committee published a report that called for public control of the railways, mines and docks and a national wages policy. A further report in May 1942 argued for works councils and the publication of "post-war plans for the provision of full and free education, employment and a civilized standard of living for everyone."

Later that year Bartlett, Richard Acland, J. B. Priestley and other members of the 1941 Committee established the socialist Common Wealth Party. The party advocated the three principles of Common Ownership, Vital Democracy and Morality in Politics. The party favoured public ownership of land and Acland gave away his Devon family estate of 19,000 acres (8,097 hectares) to the National Trust.

After the war Bartlett joined the Labour Party. However, he retired from politics at the 1950 General Election and decided to become a full-time journalist. As well as working for the Daily Chronicle he was staff reporter for the Manchester Guardian between 1954 and 1963. The author of several books, his autobiography, And Now, Tomorrow, was published in 1960. Vernon Bartlet died on 18th January 1983.

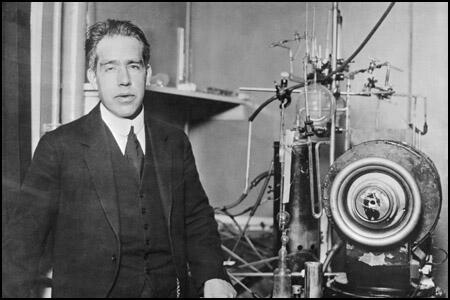

On this day in 1962 the scientist Niels Bohr died. Bohr was born in Copenhagen, Denmark, on 7th October, 1885. The son of a physiology professor he got his PhD in physics from the University of Copenhagen in 1911. Bohr worked with Ernest Rutherford in Manchester (1912-16) where he developed a model of atomic structure and helped to establish the validity of quantum theory.

In 1920 Bohr became director of the Institute of Theoretical Physics in Copenhagen. Several leading physicists went to work with Bohr including Edward Teller and Werner Heisenberg. In 1922 he won the Nobel Prize for physics. Otto Frisch, a young scientist who fled from Nazi Germany worked closely with Bohr in Copenhagen. In 1938 Frisch introduced Bohr to Lise Meitner, a Jewish refugee from Germany. Meitner explained her theory of uranium fission and argued that by splitting the atom it was possible to use a few pounds of uranium to create the explosive and destructive power of many thousands of pounds of dynamite.

At a conference held in Washington in January, 1939, Bohr explained the possibility of creating nuclear weapons. After working with Enrico Fermi and Leo Szilard, Bohr showed that only the isotope uranium-235 would undergo fission with slow neutrons.

Niels Bohr continued with his research after Denmark was invaded by the German Army. With the help of the British Secret Service he escaped to Sweden in 1943. He then moved on to the USA where he joined Robert Oppenheimer, Edward Teller, Enrico Fermi, David Bohm, James Franck, James Chadwick, Otto Frisch, Emilio Segre, Eugene Wigner, Felix Bloch, Leo Szilard and Klaus Fuchs on the Manhattan Project. Over the next two years Bohr helped develop the atom bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

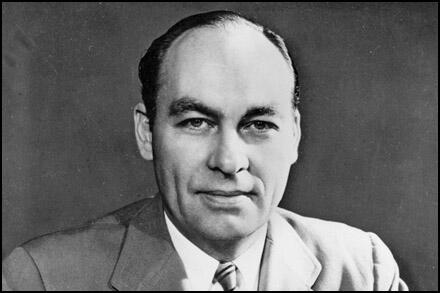

On this day in 1965 the progressive politician, Henry A. Wallace died. In late November, 1932, Raymond Moley told Wallace that President Franklin D. Roosevelt wanted to see him in Warm Springs, Georgia. Roosevelt asked Wallace if he would join his team in Washington that were drafting new legislation for when he became president. He agreed and on 6th February, 1933, Wallace was invited to become Secretary of Agriculture. Wallace waited six days before accepting the post.

President Roosevelt asked Rexford Tugwell what post he would like. He replied that he would like to be appointed assistant secretary of agriculture under Wallace. The authors of American Dreamer: A Life of Henry A. Wallace (2001) has commented: "They presented a rather odd picture together - the dapper Columbia University professor and the tousled Iowa editor - but they made a good team. They were men of ideas and shared a vision of government that was activist and progressive. Wallace knew the practical aspects of American farming in the way a sailor knew the stars. And Tugwell knew Franklin Roosevelt."

On 8th March 1933, Wallace and Tugwell met with Roosevelt and asked him to expand the scope of the special congressional session to include the agricultural crisis as well as the banking emergency. Roosevelt agreed to this suggestion and it was agreed to summon the nation's farm leaders to an "emergency conference" to be held in Washington. Wallace went on national radio and told the country: "Today, in this country, men are fighting to save their homes. That is not just a figure of speech. That is a brutal fact, a bitter commentary on agriculture's twelve years' struggle.... Emergency action is imperative."

On 11th March, Wallace reported: "The farm leaders were unanimous in their opinion that the agricultural emergency calls for prompt and drastic action.... The farm groups agree that farm production must be adjusted to consumption, and favor the principles of the so-called domestic allotment plan as a means of reducing production and restoring buying power." The conference also called for emergency legislation granting Wallace extraordinarily broad authority to act, including power to control production, buy up surplus commodities, regulate marketing and production, and levy excise taxes to pay for it all.

John C. Culver and John C. Hyde, the authors of American Dreamer: A Life of Henry A. Wallace (2001) have pointed out: "The sense of urgency was hardly theoretical. A true crisis was at hand. Across the Corn Belt, rebellion was being expressed in ever more violent terms. In the first two months of 1933, there were at least seventy-six instances in fifteen states of so-called penny auctions, in which mobs of farmers gathered at foreclosure sales and intimidated legitimate bidders into silence. One penny auction in Nebraska drew an astounding crowd of two thousand farmers. In Wisconsin farmers bent on stopping a farm sale were confronted by deputies armed with tear gas and machine guns. A lawyer representing the New York Life Insurance Company was dragged from the courthouse in Le Mars, Iowa, and the sheriff who tried to help him was roughed up by a mob."

The objective of the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) was for a reduction in food production, which would, through a controlled shortage of food, raise the price for any given food item through supply and demand. The desired effect was that the agricultural industry would once again prosper due to the increased value and produce more income for farmers. In order to decrease food production, the AAA would pay farmers not to farm and the money would go to the landowners. The landowners were expected to share this money with the tenant farmers. While a small percentage of the landowners did share the income, the majority did not.

George N. Peek, who had been placed in charge of the AAA by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, was was adamantly opposed to the production quotas, which he saw as a form of socialism. The authors of American Dreamer: A Life of Henry A. Wallace (2001) have argued: "Crusty and dogmatic, Peek still seethed with resentment over Wallace's appointment as secretary, a position he coveted. Moreover, Peek had no use for the domestic allotment plan, which was the heart of the AAA program." To Peek the plan represented "the promotion of planned scarcity" and according to his autobiography, Why Quit Our Own? (1936), he was "steadfastly against it" from the outset.

Wallace appointed Jerome Frank as the AAA's general counsel. John C. Culver has argued: "Frank was liberal, brash, and Jewish. Peek loathed everything about him. In addition, Frank surrounded himself with idealistic left-wing lawyers... whom Peek also despised." This included Adlai Stevenson, Alger Hiss and Lee Pressman. Peek later wrote that the "place was crawling with... fanatic-like... socialists and internationalists."

Peek's main objective was to raise agricultural prices through cooperation with processors and large agribusinesses. Other members of the Agricultural Department such as Jerome Frank was primarily concerned to promote social justice for small farmers and consumers. On 15th November, 1933, Peek demanded that Wallace should fire Frank for insubordination. Wallace, who agreed more with Frank than Peek, refused.

George N. Peek became completely disillusioned with the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA). He wrote in his autobiography, Why Quit Our Own? (1936): "There is no use mincing words... The AAA became a means of buying the farmer's birthright as a preliminary to breaking down the whole individualistic system of the country." However, it was clear that President Franklin D. Roosevelt supported Wallace over Peek.

In December 1933, Wallace accompanied Roosevelt on a visit to Warm Springs. Peek seized the opportunity to announce a half-million-dollar plan to subsidize the sale of butter in Europe. Peek's action was intended as a declaration of independence, but Rexford Tugwell, acting secretary in Wallace's absence, took it as insubordination. Tugwell wrote in his autobiography that "it was becoming obvious that if we did not get rid of George Peek, he would get rid of us." He said this to Roosevelt and it was agreed that Peek should be moved from the AAA.

A few days later, Wallace made a speech where he said the dairy program had been a failure. Although he did not make reference to George N. Peek, it was clearly a comment of his policy at the AAA. John Franklin Carter commented: "That is the coolest political murder that has been committed since Roosevelt came into office." Peek resigned from the AAA on 11th December, 1933. The same day, President Roosevelt named Peek his Special Advisor on Foreign Trade.

Under the terms of the Agricultural Adjustment Act farmers were paid money not to grow crops and not to produce dairy produce such as milk and butter. The money to pay the farmers for cutting back production of about 30% was raised by a tax on companies that bought the farm products and processed them into food and clothing.

Henry A. Wallace controversially agreed that hog farmers should be allowed to slaughter pigs weighing less than one hundred pounds instead of allowing them to reach their usual market weight of two hundred pounds. It was argued that pigs would be reduced by five or six million, prices would rise, and the edible portions of the pigs could be used to feed the hungry. William E. Leuchtenburg, the author of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal (1963), has pointed out: "Wallace reluctantly agreed to a proposal of farm leaders to forestall a glut in the hog market by slaughtering over six million little pigs and more than two hundred thousand sows due to farrow. While one million pounds of salt pork was salvaged for relief families, nine-tenths of the yield was inedible, and most of it had to be thrown away. The country was horrified by the mass matricide and infanticide. When the piglets overran the stockyards, and scampered squealing through the streets of Chicago and Omaha, the nation rallied to the side of the victims of oppression, seeking to flee their dreadful fate."

Newspapers denounced Wallace's plan as "pig infanticide". Wallace was surprised by the criticism as it is "just as inhumane to kill a big hog as a little one". Wallace added: "To hear them talk, you would have thought that pigs are raised for pets. Nor would they realize that the slaughter of little pigs might make more tolerable the lives of a good many human beings being dependent on hog prices." Some one million pounds of pork, and pork by-products, such as lard and soap, was distributed to poor. Wallace pointed out: "Not many people realized how radical it was - this idea of having the Government buy from those who had too much, in order to give to those who had too little."

Wallace was popular with farmers. As Frances Perkins pointed out: "Wallace was very able, clear-thinking, high-minded, a man of patriotism and nobility of character. Her had a following among farmers. He was one of the few people with an agricultural background who had begun to make himself comprehensible to the industrial working people of the country." The journalist, John Franklin Carter, commented: "He is as earthy as the black loam of the corn belt, as gaunt and grim as a pioneer. With all of that, he has an insatiable curiosity and one of the keenest minds in Washington, well-disciplined and subtle, with interests and accomplishments which range from agrarian genetics to astronomy. If the young men and women of this country look to the west for a liberal candidate for the Presidency - as they may in 1940 - they will not be able to overlook Henry Wallace."

Sherwood Anderson was another who was impressed with Wallace: "He has an inner rather than an outward smile... perhaps just at bottom sense of the place in life of the civilized man... no swank... something that gives us confidence." However, others accused him of faddism and pointed out that on one occasion lived on corn meal and milk after learning that this had been the food of Julius Caesar and his army in Gaul.

Wallace and Rexford Tugwell were seen as the leading liberals in Roosevelt's government. Tugwell defended his liberal views by arguing: "Liberals would like to rebuild the station while the trains are running; radicals prefer to blow up the station and forgo service until the new structure is built." Wallace and Tugwell had a strong following amongst liberals in the Democratic Party. John C. Hyde commented "the reformers... saw in Wallace a reflection of themselves: young, idealistic, open-minded, comfortable with intellectual give-and-take, and repulsed by the excesses of capitalism."

Henry A. Wallace played an important role in the 1936 Presidential Election. The Des Moines Register reported: "Of all the members of the New Deal cabinet, Wallace - originally a nonpartisan selection - now bears the most political responsibility and has been shoved forward as the No. 2 in the campaign." During the election campaign, President Franklin D. Roosevelt was attacked for not keeping his promise to balance the budget. The National Labour Relations Act was unpopular with businessmen who felt that it favoured the trade unions. Some went as far as accusing Roosevelt of being a communist. However, the New Deal was extremely popular with the electorate and Roosevelt easily defeated the Republican Party candidate, Alfred M. Landon, by 27,751,612 votes to 16,681,913.

Wallace continued to argue for government intervention. On 1st April, 1937, Wallace gave a lecture at the University of North Carolina entitled, Technology, Corporations and the General Welfare, where he argued the country could no longer afford the luxury of laissez-faire capitalism: "The impact of modern technology through the corporate form of organization, and the control by corporations over price and production, are such as to make the problem of the one-third of the population at the bottom of the heap practically hopeless unless the government steps in definitely and powerfully on behalf of the general welfare.

Wallace's left-wing views made him increasingly unpopular in the Democratic Party and Roosevelt came under pressure to drop him as his vice-president in 1944. Jack L. Bell argued: "The Vice President knows from experience that if President Roosevelt is a candidate he will pick his own running-mate. His friends say that if he is able to demonstrate that he speaks for the liberals and labor it will be difficult for Mr. Roosevelt to cast him aside."

Even liberals in Roosevelt's administration such as Harry Hopkins argued that Wallace was too left-wing and should be dropped as vice-president for the 1944 Presidential Election. A public opinion poll showed that Wallace was a popular figure and a survey to discover who Roosevelt's running-mate should be, suggested that he should be selected: The results were as follows: Wallace (46%), Cordell Hull (21%), James Farley (13%), Sam Rayburn (12%), James F. Byrnes (5%) and Harry F. Byrd (3%).

Walter Lippmann argued against Wallace being nominated as he considered him to be emotionally unsuited to be president: "We can't take the risk. This man may go crazy. we know that Roosevelt is not immortal." Robert Hannegan, the chairman of the Democratic National Committee, was totally opposed to Wallace and suggested that he should select Harry S. Truman instead. Roosevelt told Wallace he had a problem because some people were telling him that they thought he was "a Communist - or worse".

At the Democratic National Convention in 1944 Wallace upset most of the party bosses by making a passionate defence of liberalism. "The future belongs to those who go down the line unswervingly for the liberal principles of both political democracy and economic democracy regardless of race, color or religion. In a political, educational and economic sense there must be no inferior races. The poll tax must go. Equal educational opportunities must come. The future must bring equal wages for equal work regardless of sex or race. Roosevelt stands for all this. That is why certain people hate him so. That also is one of the outstanding reasons why Roosevelt will be elected for a fourth time."

In McCook, Nebraska, a dying George Norris heard the speech and immediately sent him a letter: "I do not suppose it would be considered a proper speech for that occasion by the politicians. If you had been trying to appease somebody you made a mistake, but you were talking straight into the faces of your enemies who were trying to defeat you, and no matter what they may think or what effect it may have on them, the effect on the country and all those who will read that speech is that it was one of the most courageous exhibitions ever seen at a political convention in this country."

Claude Pepper organized a parade in favour of Wallace. Jennet Conant, the author of The Irregulars: Roald Dahl and the British Spy Ring in Wartime Washington (2008), has argued: "Senator Claude Pepper, who was with the Florida delegation, thought that Wallace parade had pulled it off. From what he could see, standing on his chair and looking down at the forest of state standards raised in the air, it appeared that 'if a vote was taken that evening, Wallace would be nominated'. The Wallace demonstrators looked like they were about to riot. Hannegan, realizing that emotions had become too hot, hastily yelled at the party chairman to adjourn the night session. Pepper tried to reach the platform, to appeal to the floor not to adjourn. With a bang of his gavel, it was over. The crowd groaned in protest, but the police were already ushering them toward the exists."

The speech put President Franklin D. Roosevelt in a difficult position and he now refused to come out openly for Wallace. The vote at the end of the first ballot was 429 to Wallace and 319 for Harry S. Truman. Conservatives in the party now decided to take action. Other candidates, Herbert O'Conor and John Hollis Bankhead, withdrew in favour of Truman. Robert Hannegan now approached others to change their vote. Hannegan later said, he would like his tombstone to be inscribed with the words: "Here lies the man who stopped Henry Wallace from becoming President of the United States." At the next ballot Truman won 1,031 votes against Wallace's 105. It later emerged that Bernard Baruch had offered Roosevelt a million dollars if he ran on a ticket without Wallace.

In the 1944 Presidential Election Roosevelt and Truman comfortable beat Thomas E. Dewey and John W. Bricker by 25,612,916 votes (53.4%) to 22,017,929 votes (45.9%). Wallace loyally supported Roosevelt during the election and he was rewarded by being given the post of Secretary of Commerce. He retained the post after Roosevelt died on on 7th May, 1945. Although most of the liberals in the administration lost their posts.

Henry A. Wallace became highly critically of the foreign policy of Harry S. Truman and James F. Byrnes. In his diary, he wrote: "It is obvious to me that the cornerstone of the peace of the future consists in strengthening our ties of friendship with Russia. It is also obvious that the attitude of Truman, Byrnes, and both the war and navy departments is not moving in this direction. Their attitude will make for war eventually."

On 12th September, 1946 Wallace made a speech about the atom bomb: "During the past year or so, the significance of peace has been increased immeasurably by the atom bomb, guided missiles, and airplanes which soon will travel as fast as sound. Make no mistake about it - another war would hurt the United States many times as much as the last war... He who trusts in the atom bomb will sooner or later perish by the atom bomb - or something worse. I say this as one who steadfastly backed preparedness throughout the thirties. We have no use for namby-pamby pacifism. But we must realize that modern inventions have now made peace the most enticing thing in the world - and we should be willing to pay a just price for peace."

Wallace went on to argue that the government needed to tackle racism: "The price of peace - for us and for every nation in the world - is the price of giving up prejudice, hatred, fear and ignorance.... Hatred breeds hatred. The doctrine of racial superiority produces a desire to get even on the part of its victims. If we are to work for peace in the rest of the world, we here in the United States must eliminate racism from our unions, our business organizations, our educational institutions, and our employment practices. Merit alone must be the measure of men."

James F. Byrnes was furious about the speech and he sent a message to President Harry S. Truman: If it is not possible for you, for any reason, to keep Mr. Wallace, as a member of your cabinet, from speaking on foreign affairs, it would be a grave mistake from every point of view for me to continue in office, even temporarily." Truman wanted to keep Byrnes and after complaints from James Forrestal, Secretary of Defence, he forced Wallace to resign on 20th September, 1946.

Wallace received several letters of support. Albert Einstein wrote: "Your courageous intervention deserves the gratitude of all of us who observe the present attitude of our government with grave concern. Hellen Keller also praised Wallace: "Rejoicing I watch you faring forth on a renewed pilgrimage looking not downwards to ignoble acquiescence or around at fugitive expediency, but upward to mind-quickening statecraft and life-saving peace for all lands." Thomas Mann sent a telegram: "Like millions of good Americans we not only share your views on foreign policy but are deeply impressed with your courage and consistency in defending them."

After he left government Wallace returned to journalism. Michael Straight, the publisher of The New Republic, appointed Wallace as editor of the magazine on a salary of $15,000 a year. Money was not an issue for Wallace as Pioneer Hi-Bred earned more than $150,000 in dividends in 1946. Wallace wrote that: "As editor of The New Republic I shall do everything I can to rouse the American people, the British people, the French people, the Russian people and in fact the liberally-minded people of the whole world, to the need of stopping this dangerous armament race."

Wallace formed the Progressive Citizens of America (PCA). Members included Rexford Tugwell, Paul Robeson, W.E.B. Du Bois, Arthur Miller, Dashiell Hammett, Hellen Keller, Jo Davidson, Thomas Mann, Aaron Copland, Claude Pepper, Eugene O'Neill, Glen H. Taylor, John Abt, Edna Ferber, Thornton Wilder, Carl Van Doren, Anne Braden, Carl Braden, Fredric March and Gene Kelly. A group of conservatives, including Henry Luce, Clare Booth Luce, Adolf Berle, Lawrence Spivak and Hans von Kaltenborn, sent a cable to Ernest Bevin, the British foreign secretary, that the PCA were only "a small minority of Communists, fellow-travelers and what we call here totalitarian liberals." Winston Churchill agreed and described Wallace and his followers as "crypto-Communists".

Wallace also led the attacks against the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). On 19th May, 1947, he argued: "We burned an innocent woman on charge of witchcraft. We earned the scorn of the world for lynching negroes. We hounded labor leaders and socialists at the turn of the century. We drove 100,000 innocent men and women from their homes in California because they were of Japanese ancestry.... We branded ourselves forever in the eyes of the world for the murder by the state of two humble and glorious immigrants - Sacco and Vanzetti.... These acts today fill us with burning shame. Now other men seek to fasten new shame on America.... I mean the group of bigots first known as the Dies Committee, then the Rankin Committee, now the Thomas Committee - three names for fascists the world over to roll on their tongues with pride."

Americans for Democratic Action (ADA), that included Arthur Schlesinger, Eleanor Roosevelt, Walter Reuther, Hubert Humphrey, Asa Philip Randolph, John Kenneth Galbraith,Walter F. White,Louise Bowen, Chester Bowles, Louis Carlo Fraina, Stewart Alsop, Reinhold Niebuhr, George Counts, David Dubinsky and Joseph P. Lash, refused to support Wallace and the Progressive Citizens of America (PCA) because they objected to the fact that it allowed members of the American Communist Party (ACP) to join: "We reject any association with Communism or sympathizers with communism in the United States as completely as we reject any association with Fascists or their sympathizers."

In January 1948, The New Republic reached a circulation of a record 100,000. Michael Straight was unhappy with Wallace's involvement of the Progressive Citizens of America, his collaboration with the ACP. Straight was a supporter of the Marshall Plan and the anti-communism policies of President Harry S. Truman and therefore decided to sack Wallace as editor.

Wallace decided to stand in the 1948 Presidential Election. His running-mate was Glen H. Taylor, the left-wing senator for Idaho. Wallace's chances were badly damaged when William Z. Foster, head of the American Communist Party, announced he would be supporting Wallace in the election. The New York Post reported: "Who asked Henry Wallace to run? The answer is in the record. The Communist Party through William Z. Foster and Eugene Dennis were the first... The record is clear. The call to Wallace came from the Communist Party and the only progressive organization admitting Communists to its membership."

The programme of Wallace and Taylor included new civil rights legislation that would give equal opportunities for black Americans in voting, employment and education, repeal of the Taft-Hartley Bill and increased spending on welfare, education, and public works. Their foreign policy program was based on opposition to the Truman Doctrine and the Marshall Plan.

Wallace received support from Pete Seeger and Paul Robeson and they agreed to appear with him in Burlington, North Carolina. Seeger later recalled: "There were times when a song lightened the atmosphere. I think it probably helped prevent people from getting killed. It was a very - touch and go proposition, that tour. A number of people thought Wallace was going to be assassinated... The police allowed some of the Ku Klux Klan to get away - with throwing things. Once they found out they could get away with that, then they really descended."

David King Dunaway has pointed out: "Monday morning, August 30, 1948, fifteen cars in Wallace's contingent brought Seeger and the candidate to the textile town of Burlington, North Carolina. A grim mood hung over the entourage: The night before, a supporter had been stabbed twice by anti-Wallace crowds. A hostile throng of 2,500 awaited the caravan. It took four policemen to clear the road for the automobiles to reach the public square.... The driver of the lead car, Marge Frantz, was an immediate target. The sight of blacks and whites in the same convertible (the top fortunately rolled up) sent a shock wave through the already excited crowd. A few cars back, Pete sat guarding his banjo and guitar. The angry Southerners crawled onto the hood of his car and peered down inside as it slowed to a halt. The mob started banging on the car doors, and the shell of metal must have seemed awfully thin.

He waited coolly as the crowd pressed in, yelling obscenities and 'Go back to Russia.' No one seemed to be in the mood for a sing-along. According to the plan, Seeger was supposed to leave the car, wait while a mike was positioned, and lead the crowd in group singing. But when he stuck his head out, the eggs started to fly. One hit Wallace, spattering his white shirt. It was clear no mike would be set up... There wasn't even time to tune up, when no amount of banjo picking was going to stop the cold war."

Wallace travelled to the Deep South and called for the end of the Jim Crow laws. He was attacked at every point he stopped and made a speech. One of his followers said: "You can call us black, or you can call us red, but you can't call us yellow." Wallace commented: "To me, fascism is no longer a second-hand experience. No, fascism has become an ugly reality - a reality which I have tasted it neither so fully nor so bitterly as millions of others. But I have tasted it."

Glen H. Taylor also campaigned against racial discrimination. In Alabama he entered a public hall through an entrance marked "Colored". He pointed out in his autobiography, The Way It Was With Me (1979): "I was a United States senator, and by God, I wasn't going to slink down a dark alley to get to a back door for Bull Connor or any other bigoted son of a bitch. I'd go in any goddamned door I pleased, and I pleased to go in that door right there." Taylor was arrested and at a subsequent trial he was fined $50 and given a 180-day suspended sentence on charges of breach of peace, assault, and resisting arrest.

Harry S. Truman and his running mate, Alben W. Barkley, polled more than 24 million popular votes and 303 electoral votes. His Republican Party opponents, Thomas Dewey and Earl Warren, won 22 million popular votes and 189 electoral votes. Storm Thurmond ran third, with 1,169,032 popular and 39 electoral votes. Wallace was last with 1,157,063 votes. Nationally he got only 2.38 per cent of the total vote. Only one supporter, Vito Marcantonio, won his seat in Congress.