Football Battalion

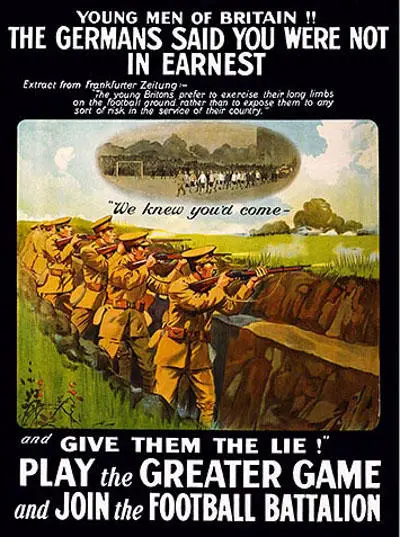

Cricket and rugby competitions stopped almost immediately after the outbreak of the First World War. However, the Football League continued with the 1914-15 season. Most football players were professionals and were tied to clubs through one-year renewable contracts. Players could only join the armed forces if the clubs agreed to cancel their contracts.

On 12th December 1914 William Joynson Hicks established the 17th Service (Football) Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment. This became known as the Football Battalion. According to Frederick Wall, the secretary of the Football Association, the England international centre-half, Frank Buckley, was the first person to join the Football Battalion. At first, because of the problems with contracts, only amateur players like Vivian Woodward, and Evelyn Lintott were able to sign-up.

As Frank Buckley had previous experience in the British Army he was given the rank of Lieutenant. He eventually was promoted to the rank of Major. Within a few weeks the 17th Battalion had its full complement of 600 men. However, few of these men were footballers. Most of the recruits were local men who wanted to be in the same battalion as their football heroes. For example, a large number who joined were supporters of Chelsea and Queen's Park Rangers who wanted to serve with Vivian Woodward and Evelyn Lintott.

According to Ian Nannestad of Soccer History: "The organisers hoped to enlist a full battalion of 1,350 men apparently from the ranks of both amateur and professional players and staunch supporters of senior clubs... Recruitment at the time was principally aimed at unmarried men, of whom there were estimated to be around 600 amongst the ranks of professional footballers. A significant proportion of these were based in the north of England, although the battalion announced it would only recruit men from clubs south of the River Trent. Initial interest was high, with 4-500 present at the meeting, but of these only 35 enlisted on the day, and by the end of the year The Sportsman recorded just 34 additional names."

By March 1915, it was reported that 122 professional footballers had joined the battalion. This included the whole of the Clapton Orient (later renamed Leyton Orient) first team. Three of them were later killed on the Western Front. At the end of the year Walter Tull who had played for Tottenham Hotspur, Northampton Town and Glasgow Rangers joined the battalion. Major Frank Buckley soon recognised Tull's leadership qualities and he was quickly promoted to the rank of sergeant.

Three members of the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee visited Upton Park and made an appeal for volunteers during half-time. Joe Webster, the West Ham United goalkeeper, was one of those who joined the Football Battalion as a result of this appeal.

On 15th January 1916, the Football Battalion reached the front-line. During a two-week period in the trenches four members of the Football Battalion were killed and 33 were wounded. This included Vivian Woodward who was hit in the leg with a hand grenade. The injury to his right thigh was so serious that he was sent back to England to recover. Woodward did not return to the Western Front until August 1916.

The Football Battalion had taken heavy casualties during the Somme offensive in July. This included the death of England international footballer, Evelyn Lintott. The battle was still going on when Woodward arrived but the fighting was less intense. However, on 18th September a German attack involving poison gas killed 14 members of the battalion.

Major Frank Buckley was also seriously injured during this offensive when metal shrapnel had hit him in the chest and had punctured his lungs. George Pyke, who played for Newcastle United, later wrote: "A stretcher party was passing the trench at the time. They asked if we had a passenger to go back. They took Major Buckley but he seemed so badly hit, you would not think he would last out as far as the Casulalty Clearing Station." Buckley was sent to a military hospital in Kent and after operating on him, surgeons were able to remove the shrapnel from his body. However, his lungs were badly damaged and was never able to play football again.

Walter Tull also took part in the major Somme offensive. Tull survived this experience but in December 1916 he developed trench fever and was sent home to England to recover. Tull had impressed his senior officers and recommended that he should be considered for further promotion. When he recovered from his illness, instead of being sent back to France, he went to the officer training school at Gailes in Scotland. Despite military regulations forbidding "any negro or person of colour" being an officer, Tull received his commission in May, 1917. Lieutenant Tull was sent to the Italian front. This was an historic occasion because Tull was the first ever black officer in the British Army. He led his men at the Battle of Piave and was mentioned in dispatches for his "gallantry and coolness" under fire.

In January 1917 Major Frank Buckley was back on the Western Front. The Football Battalion attacked German positions at Argenvillers. Buckley was "mentioned in dispatches" as a result of the bravery he showed during the hand-to-hand fighting that took place during the offensive. The Germans used poison gas during this battle and Buckley's already damaged lungs were unable to cope and he was sent back home to recuperate.

Walter Tull stayed in Italy until 1918 when he was transferred to France to take part in the attempt to break through the German lines on the Western Front. On 25th March, 1918, 2nd Lieutenant Tull was ordered to lead his men on an attack on the German trenches at Favreuil. Soon after entering No Mans Land Tull was hit by a German bullet. Tull was such a popular officer that several of his men made valiant efforts under heavy fire from German machine-guns to bring him back to the British trenches. These efforts were in vain as Tull had died soon after being hit. Tull's body was never found.

Major Frank Buckley kept a record of what happened to the men under his command. He later wrote that by the mid-1930s over 500 of the battalion's original 600 men were dead, having either been killed in action or dying from wounds suffered during the fighting.

Primary Sources

(1) The Sportsman (16th December 1914)

Yesterday’s meeting at the Fulham Town Hall, kindly lent for the purpose by the Mayor, Mr H. G. Norris, must be pronounced a success. It was arranged for the purpose of giving a send-off to the Footballers’ Battalion, officially known as the 17th Service Battalion Middlesex Regiment of Kitchener’s Army, and was attended by four or five hundred officials and players and others interested in the Association game. It had been intended to use the smaller hall, but the players trooped in as one party just before the time fixed (half-past 3) in such numbers that a move was made to the larger one, which was practically filled.

Mr W. Joynson-Hicks, M.P., occupied the chair, having on his right Mr H. G. Norris (the Mayor of Fulham) and on his left the Right Hon W. Hayes-Fisher, P.C., M.P., whilst others on the platform were the Right Hon Lord Kinnaird, K.T. (President of the Football Association), who could not arrive until some time after the meeting had been in progress, Col Grantham, Capt Whiffen, Capt Wells-Holland (Clapton Orient), Messrs J. B. Skeggs (Millwall) and F. J. Wall, who is acting as hon sec of the project. In the body of the hall were directors and officials of most of the leading professional clubs in and around the metropolis, including Messrs C. D. Crisp, J. Hall, and G. Morrell (The Arsenal), A. J. Palmer (Chelsea), S. Bourne (Crystal Palace), T. A. Descock, M. F. Cadman, and P. McWilliam (Tottenham Hotspur), P. Kelso (Fulham), and others too numerous to mention.

The Chairman opened proceedings with a splendid speech, in which he stated that most of those present were fully aware of the reason for which they had assembled, nor were they ignorant of the amount of correspondence and articles which had been appearing in the Press attacking footballers, football clubs, and even those who looked on. But the present was not a meeting called to answer those attacks. The country was at war with a great Power, Germany, and not until the stern struggle was over was it the time for recriminations. There was for the time being no party in the House of Commons, and he wished them to take the same line. Everybody to-day was for the State, everybody against Germany: all were anxious to make the path of those in charge easy, and assure ultimate victory. They could only endure, and then if they thought it worth while after the war was over they could answer their critics. His own view was that that magnificent meeting was an answer, and the best that could be made was to ensure the successful formation of the Footballers’ Battalion , or a Footballers’ Brigade.

(2) The London Gazette, report on the death of Donald Bell (8th September, 1916)

For most conspicuous bravery. During an attack a very heavy enfilade fire was opened on the attacking company by a hostile machine gun. 2nd Lt. Bell immediately, and on his own initiative, crept up a communication trench and then, followed by Corpl. Colwill and Pte. Batey, rushed across the open under very heavy fire and attacked the machine gun, shooting the firer with his revolver, and destroying gun and personnel with bombs. This very brave act saved many lives and ensured the success of the attack. Five days later this very gallant officer lost his life performing a very similar act of bravery.

(3) The Guardian (25th March, 1998)

Playing at inside left, Tull's future looked bright. Then, in a game at Bristol City in 1909, he was racially abused by fans in what the Football Star called "language lower than Billingsgate". The incident was deeply traumatic for Tull and the club. The following season, he played only three first-team games; the season after, he was sold for "a heavy transfer fee" to Northampton Town. There, Tull flourished again, playing 110 first-team games for the club, mostly at wing-half. He was probably their biggest star. In 1914, he was on the point of signing for Glasgow Rangers. Then came war. It was perhaps inevitable, given the spirit of muscular Christianity in which he was raised, that Tull should make a swift transition from sport to war. What was less inevitable was that he should conduct himself with even more distinction on the battlefield than on the playing field. Yet he did. He enlisted in the 17th (1st. Football) Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment, alongside many other professional footballers. By 1916, he had been made a sergeant. Among other actions, he was involved in the murderous first battle of the Somme. We can only guess the horrors he endured, but they did not break him.

(4) Walter Tull's commanding officer in the 23rd Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment, sent a letter to Edward Tull after the death of his brother (March, 1918)

He was popular throughout the battalion. He was brave and conscientious. The battalion and company had lost a faithful officer, and personally I have lost a friend.

(5) Leigh Roose, letter to George Holley from Gallipoli (June, 1915)

If ever there was a hell on this occasionally volatile planet then this oppressively hot, dusty, diseased place has to be it. If I have seen the fragments of one plucky youth whose body... or what there remains of it... has been swollen out of all proportion by the sun, I have seen several hundred. The bombardment is relentless to the extent that you become accustomed to its tune, a permanent rata-tat-tat complemented by bursting shells... and vet at night the stars are so bright in this largest of skies that one cannot help but be pervaded with a feeling of serenity, peculiar as that appears.

(6) London Gazette (21st September 1916)

Private Leigh Roose, who had never visited the trenches before, was in the sap when the flammenwerfer attack began. He managed to get back along the trench and, though nearly choked with fumes with his clothes burnt, refused to go to the dressing station. He continued to throw bombs until his arm gave out, and then, joining the covering party, used his rifle with great effect.

(7) Ian Nannestad, Soccer History (Issue 1)

How successful was the Footballers’ Battalion in its early stages? The organisers hoped to enlist a full battalion of 1,350 men apparently from the ranks of both amateur and professional players and staunch supporters of senior clubs. Athletic News dreamed of a future where there might be “the Chelsea Company, the Tottenham Company, the Millwall Company, the Fulham Company, and so on,” but the reality was somewhat different in relation to professional players.

Recruitment at the time was principally aimed at unmarried men, of whom there were estimated to be around 600 amongst the ranks of professional footballers. A significant proportion of these were based in the north of England, although the battalion announced it would only recruit men from clubs south of the River Trent. Initial interest was high, with 4-500 present at the meeting, but of these only 35 enlisted on the day, and by the end of the year The Sportsman recorded just 34 additional names.

Student Activities

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)

Football and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Football on the Western Front (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)