Vivian Woodward

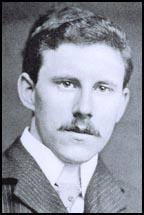

Vivian Woodward was born in Kennington, Surrey, on 3rd June 1879. He was the seventh of eight children born to John and Anna Woodward. Vivian's father was a successful architect and a Freeman of the City of London.

The family also owned a home in Clacton-on-Sea, a town established in 1871 to cater specifically for the wealthy upper middle classes. Vivian went to the private school, Ascham College. An outstanding sportsman, he played cricket for the school First XI at the age of twelve. He was an even better footballer, but his father insisted he concentrated on cricket and tennis while at school.

Woodward was slightly built and opponents used dubious tactics to counteract his speed and skill. However, he soon became the star of the Ascham College team. His father eventually relented and at the age of 16 he was allowed to play centre forward for Clacton Town in the North Essex League First Division. In fact, John Woodward now became vice-president of the club. The local newspaper, the Clacton Graphic, was soon reporting that "V. J. Woodward was the back-bone and centre of attraction in the team".

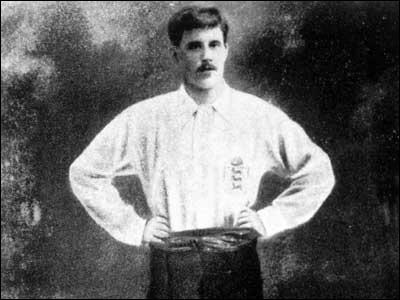

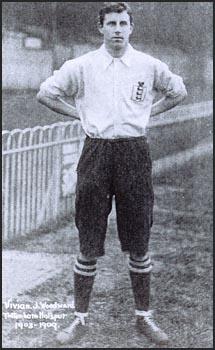

Vivian Woodward became an architect like his father and resisted all attempts to become a professional footballer. However, he did agree to play on amateur terms for Tottenham Hotspur in the Southern League. At the time Spurs was considered to be one of the best teams in the country having won the 1901 FA Cup Final against Sheffield United.

Woodward's work came first and on several occasions he did not play for the team for business reasons. He also missed the first few games of every season because of his commitment to the Spencer Cricket & Lawn Tennis Club. . He was one of England's best tennis players and tended to put this sport before football. When he signed for Spurs the club announced that he would play for them whenever it was "convenient for him to play."

Woodward remained an amateur throughout his football career. He came from a wealthy family and did not even claim bus or train fares or other legitimate expenses. The Tottenham & Stamford Hill Times carried an article about professionalism in football soon after Woodward signed for Tottenham Hotspur: "Football is a profession is making great strides in popularity among the masses of today. A few years back professional football was only considered good enough for the poorest class, and for a man in a fair position to enter the ranks of the pro's - well, he was a fool, at least, that was the opinion of the majority of the south."

Woodward's form for Tottenham Hotspur was so good that he won his first full international cap for England against Ireland on 14th February, 1903. He scored two goals in England's 4-0 victory. The following day the Times reported that Woodward "certainly added to the reputation he is making as a centre-forward." Another journalist described Woodward as: "The human chain of lightning, the footballer with magic in his boots."

In its next edition the Sporting Chronicle remarked: "Woodward is quite young, stands 5ft 10ins, and tips the beam at 11 stone. I should prefer him to be a little heavier, but weight will come... With a subtle craft tucked away in his toes he combines most adroit head work, and between the two he opens out the game in dazzling style. Woodward is a great initiator, the personification of unselfishness, is quick to grasp the ever-changing situation of the game, and, above all, is very cool."

The following month Woodward played for England against Wales. Woodward scored in England's 2-1 win. C. B. Fry was very impressed with Woodward's performance. He wrote: "It must be very satisfactory to the selectors to find Woodward so great a success at centre forward, especially as he is likely to improve for several years to come... It will be a surprise and a great disappointment now if he does not get his cap against Scotland."

James Catton, Britain's top football journalist at the time, thought that Woodward was a better inside-right than centre-forward: "Much was required to arouse Vivian John Woodward to resentment because his game was all art and no violence. It may be that Woodward had hard experiences in some of his matches against Scotland, while he was played in the centre, but there came a day when he was moved to inside-right, and there he was at his very best - his perfect heading and his deft passes having great effect."

Woodward was selected for the Scotland game that took place on 4th April, 1903. Woodward beat Ted Doig in the Scotland goal after only 10 minutes but England lost the game 2-1. It had been a great start to his international career scoring four goals in his first three games. C. B. Fry and other commentators compared him to the great Gilbert Oswald Smith, who Woodward had replaced in the England team.

Frederick Wall, the president of the Football Association, thought that Woodward was a better player than Smith: "I am going to make a statement that may be considered startling, but as my opinion is honest, I am not concerned if it does not agree with the views of others. G.O. Smith and Woodward were both great players, but the Tottenham and Chelsea forward was the better. Why was he the better footballer? Woodward was the more versatile, the more consistent, and cleverer with his heading... And it should be remembered that Woodward... was faster than he looked, and that he had a neat trick of feinting, or what some call 'selling the dummy'. The most unselfish of forwards, he was a master-model of team work."

Although Woodward always played for England but was not always available for Tottenham Hotspur. In the 1906-07 season Woodward did not play his first game until the start of October. The Tottenham Herald reported: "After an indifferent beginning the Spurs... are perhaps the most respected team in the Southern League... The introduction of V. J. Woodward has had a most beneficial effect... He has pulled the forwards together, and the team has brightened up all round."

Woodward was only slightly built and he was often the target of some very rough tackling. This resulted him in missing a lot of games through injury. After a game against Fulham on 29th October, 1906, when Woodward took a terrible battering, newspapers called for referees and football authorities to do more to protect skillful players against the crude tactics of defenders.

As the journalist, Arthur Haig-Brown, pointed out in 1903: "It is a 1,000 pities that his lack of weight renders him a temptation which the occasionally unscrupulous half-back finds himself unable to resist." However, he went onto point out that this did not stop him scoring a lot of goals: "His record of goals both in League matches and in Internationals is a flattering one, for, all said and done, the most important duty of a centre forward is to find the net, and find it often."

Although he was only 5ft 10ins tall and weighed less than 11 stone, Woodward was considered the best header of the ball in football. Frederick Wall, the president of the Football Association, argued that in 50 years of watching football, only Sandy Turnbull and Dixie Dean could compare with Woodward in the air. As he pointed out: "Woodward was as dangerous near goal with his head as any man I have seen."

In 1906 the Football Association began organizing amateur internationals. The England team went on an international tour and in their first game they beat France 15-0 with Woodward scoring eight goals.

Woodward returned to the full-international side on 6th April 1907. The England team included Steve Bloomer, Bob Crompton, William Wedlock and Colin Veitch but could only draw 1-1 against Scotland.

Woodward arrived late again for the start of the 1907-08 season. On 6th September, 1907, the club reported that: "V. J. Woodward will remain faithful to cricket and tennis for a little longer, and therefore will not turn out for the Spurs just yet." That year Woodward was appointed as a director of the club. Woodward played his first game on 5th October. After a slow start he began scoring goals as Tottenham Hotspur climbed up the table. Woodward scored both goals in Spurs' 2-1 victory over Millwall. The referee was unsure if the ball had crossed the line for the first goal. Woodward declared that it did and the referee accepted this claim as he said it "was well-known that Woodward would not cheat."

Normally, Woodward refused to play over Christmas. However, that year, because Tottenham Hotspur stood a good chance of winning the title, Woodward played in the game against Northampton Town on Christmas Day. Woodward scored both goals in the 2-0 win. The Tottenham Herald argued that "Woodward's value to the Spurs seems to increase with every match. On Wednesday (25th December) he was again the chief figure in the home front line, and is adding to his reputation by scoring goals, eleven in the last four matches."

Woodward was appointed captain of the England team that played Ireland on the 5th February, 1908. He scored the second goal in England's 3-1 victory. The following month he scored a hat-trick in a 7-1 win over Wales. The next game was against Scotland. The England team included George Hilsdon, Bob Crompton, William Wedlock and Evelyn Lintott but could only draw 1-1.

The constant calls on Woodward's services in both full and amateur internationals meant that he missed a lot of Spurs' end of season matches, with the result that they won just four out of their last ten fixtures. Woodward went on tour with the England team in June 1908. This included a 11-1 victory over Austria, with Woodward scoring four of the goals.

Tottenham Hotspur was elected to the Second Division of the Football League in 1908. This time Woodward agreed to play for the team from the start of the season. In their first game against Wolverhampton Wanderers Woodward scored Spurs' first ever Football League goal after only six minutes. This 1-0 victory was followed by 19 more and at the end of the season Spurs finished in second place to Bolton Wanderers. Spurs had been promoted to football's First Division after just one year in the Football League.

The 1908 Olympic Games took place in London. Woodward was captain of the England team that beat Sweden (12-1) and Holland (4-0) to reach the final against Denmark. England won the gold medal by beating Denmark 2-0 on 24th October, 1908. Also in the team was Kenneth Hunt of Wolverhampton Wanderers and Harry Stapley of West Ham United.

Woodward is in the centre of the front row. Harry Stapley is sitting to Woodward's right. William McGregor is standing on the left with Kenneth Hunt next to him.

In the summer of 1909 Woodward went on another tour of Europe as captain of England's amateur team. Woodward scored four goals in England's 9-0 win over Switzerland. He also contributed to the 11-0 victory over France in Paris.

On his return to England he announced that he intended to retire from top class football as he needed to concentrate on his architectural practice. During his time at Tottenham Hotspur he had scored 62 goals in 131 league and cup games.

Woodward decided to play instead for Chelmsford in the South Essex League. However, on 20th November, 1909, he changed his mind and announced he would play for Chelsea. It seems that Woodward was a good friend of Chelsea's chairman and he had been asked to help out during an injury crisis.

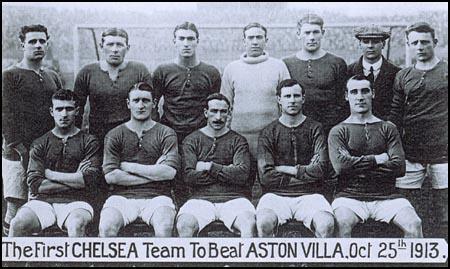

Woodward played his first game in the First Division of the Football League against Sheffield Wednesday on 27th November 1909. That game ended in defeat but the following week Chelsea beat Bristol City 4-1 with Woodward scoring two of the goals with headers. Despite the goals scored by Woodward, Chelsea was still relegated that season. Woodward's form was so good he was recalled to the international team and played in the 1-1 draw with Ireland.

In the 1910-11 season Chelsea finished in 3rd place in the Second Division. That year he played his final game for England, scoring two goals in the 6-1 victory over Wales. Over an eight year period he had scored 29 goals in 23 games (13 as captain). A record that stood until Tom Finney beat it in 1958. However, Finney played in 72 games for his 30 goals.

On 31st March, 1911, Woodward broke his arm in a game against Derby County. That year he played in only 19 out of 38 games. However, this was enough to help Chelsea finish 2nd in the league and promoted to the First Division.

The 1912 Olympic Games took place in Stockholm, Sweden. Woodward was once again captain of the England team that beat Hungary (7-0) and Finland (4-0) to reach the final against Denmark. Woodward won his second goal medal when England beat Denmark 4-2 on 4th July, 1912.

Chelsea again struggled in the First Division but with Woodward scoring 11 goals in 30 games, the club avoided relegation. The following season Chelsea finished in 8th place. Woodward, now 36 years old, was losing his pace and only scored four goals that season.

Woodward continued to play tennis and on two occasions, 1912 and 1913, reached the final of the Lawn Tennis Championship. He continued to captain the England amateur team playing his last game against Sweden on 12th June 1914. In 44 amateur internationals, Woodward scored an amazing 57 goals in 44 games.

On the outbreak of the First World War Woodward immediately joined the Territorial Army and applied for a commission in the British Army. On 9th February 1915 he was transferred to the 17th Service (Football) Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment as a second lieutenant. The Football Battalion had been founded on 12th December 1914 by William Joynson Hicks. Other members of this regiment included Walter Tull and Evelyn Lintott.

However, before he was sent to the Western Front, he still played a few games for Chelsea. That year Chelsea reached the FA Cup Final. The army agreed to release Woodward so that he could end his career at Wembley. Woodward declined the offer as he was unwilling to deprive Bob Thompson, who had been the team's regular centre-forward that season, of winning a medal. Chelsea was beaten 3-1 by Sheffield United in the final. During his time at Chelsea he had scored 34 goals in 116 games.

On 15th January 1916, the Football Battalion reached the front-line. During a two-week period in the trenches four members of the Football Battalion were killed and 33 were wounded. This included Woodward who was hit in the leg with a hand grenade. The injury to his right thigh was so serious that he was sent back to England to recover.

Woodward did not return to the Western Front until August 1916. The Football Battalion had taken heavy casualties during the Somme offensive in July. This included the death of England international footballer, Evelyn Lintott. The battle was still going on when Woodward arrived but the fighting was less intense. However, on 18th September a German attack involving poison gas killed 14 members of the battalion.

In December 1916 the Brigade Inter-Company Football Tournament took place. The 17th Middlesex beat 1st Kings (12-0) and 2nd South Staffs (10-0) on the way to the final against the 34th Brigade RFA. Understandably, the Football Battalion won the tournament. It is not known who played in these matches but it seems likely that Captain Woodward played a prominent part in this victory.

On 26th March 1917 Woodward was sent back to England to be trained as a physical training instructor at the Physical and Recreation Training School Headquarters at Aldershot. In early 1918 Woodward joined the First Army in France. After the Armistice Woodward because the coach of the British Army Football team. In 1919, aged 39, he captained the English Army to victory in the final of the "Inter-Theatre-of-War Championship" at Stamford Bridge. Woodward scored one of the goals in England's 3-2 victory over the French Army.

Vivian Woodward was eventually demobilized on 23rd May 1919 and returned to his new home at the Towers, Weeley Heath, near Clacton. Although now over forty, he still played the occasional game for Chelmsford and Clacton. On 4th March, 1920, Woodward played for Essex against Suffolk. Despite scoring a stunning goal, he could not prevent Suffolk winning 4-3. Woodward played his last game on 15th September 1920 when he turned out for Chelsea in a charity match for the families of soldiers.

Woodward also retired from his successful architectural practice in order to run a farm at Weeley Heath. He was especially proud that he had designed the main stand in the Antwerp Stadium. Woodward also established a diary business in Connaught Avenue, Frinton-on-Sea. Woodward kept his interest in football by serving as a director of Chelsea (1922-1930).

During the Second World War Woodward was a Air Raid Warden. In 1949 he was taken ill and entered a nursing home in Castlebar Road, Ealing. In 1953 he was visited by the journalist, Bruce Harris, who reported that Woodward was "bedridden, paralysed, infirm beyond his seventy-four years". Woodward complained that "no one who used to be with me in football has been to see me for two years".

Vivian Woodward died in the nursing home on 6th February, 1954.

Primary Sources

(1) The Sporting Chronicle (25th January, 1903)

This match was worth playing if it was only to discover Vivian J.Woodward, the centre of Tottenham Hotspur, who has now developed into the centre of England. Woodward is quite young, stands 5ft 10ins, and tips the beam at 11 stone. I should prefer him to be a little heavier, but weight will come. Born in the vicinity of Kennington Oval, he learned his football at a school in Clacton-on-Sea; but his experience in club play was limited to Chelmsford, and there Spurs found this amateur treasure. His form in the North and South match was a revelation to all the northern visitors, and, as a secretary to a leading Football League club remarked, he would like to put Woodward in his bag and take him away. With a subtle craft tucked away in his toes he combines most adroit head work, and between the two he opens out the game in dazzling style. Woodward is a great initiator, the personification of unselfishness, is quick to grasp the ever-changing situation of the game, and, above all, is "very cool".

(2) J. A. H. Catton, The Story of Association Football (1926)

But one would never have imagined from his conduct in private life that Woodward was a sportsman - a footballer, a runner, a cricketer, and a great lover of all games as games. He refused to make a profit out of them. It was difficult to induce him to accept even legitimate expenses, which he cut down to the lowest possible figure.

He adored his mother, and it was no uncommon sight to see mother and son wending their way to a match in company. I was introduced to this courtly lady and enjoyed a little chat with her, for she evidently followed football...

Vivian Woodward was one of the most modest of men. And in judgment one of the most charitable. Only once in all the years that we often met did I hear him criticise the conduct of another man. I felt sure that this person deserved more than the mild censure passed upon him - because a harsh remark was so foreign to Woodward's nature.

He had a great contempt for men who engaged in rough play, because he was the fairest fellow who ever put a boot to a ball. Once after a certain Cup-tie he was really wrath about the way that their opponents had treated his team. It was a replayed match in Lancashire. There was a brother amateur on the other side and he apologised to Woodward for the character of the game that his club had played. Woodward did not mind the thrashing that his club had received, but he turned to me and said: "I don't call it football at all. It was brutal."

Much was required to arouse Vivian John Woodward to resentment because his game was all art and no violence. It may be that Woodward had hard experiences in some of his matches against Scotland, while he was played in the centre, but there came a day when he was moved to inside-right, and there he was at his very best - his perfect heading and his deft passes having great effect.

(3) C. B. Fry, statement made in (January, 1903)

It must be very satisfactory to the selectors to find Woodward so great a success at centre forward, especially as he is likely to improve for several years to come, and will thus, perhaps, provide them with another "G.O.". At present I see not much likeness between Woodward and G.O. Smith. Indeed, the fact that they are both amateurs is about the full extent of the resemblance. But Woodward is a fine player who may become a great one, and he has a style of his own which is sufficiently good in itself... He is to be heartily congratulated on his success. It will be a surprise and a great disappointment now if he does not get his cap against Scotland.

(4) Alan R. Haig-Brown, The Leading Amateurs of Season 1902-03 (1903)

Perhaps the name which was most prominent in football circles during 19O2-3 was that of Vivian Woodward. G.O. Smith had taken his well-earned laurel wreath into seclusion, and an anxious eye was being cast round for his successor. Few thought he was to be found among the ranks of amateurs until the Spurs brought to light young Woodward, and England decided that what was good enough for the London Cup-fighters was good enough for her. He is a player with a great future before him. Though built somewhat on the light side he is clever and tricky, a master of the art of passing. It is a 1,000 pities that his lack of weight renders him a temptation which the occasionally unscrupulous half-back finds himself unable to resist. His record of goals both in League matches and in Internationals is a flattering one, for, all said and done, the most important duty of a centre forward is to find the net, and find it often.

(5) Frederick Wall, 50 Years of Football (1935)

I am going to make a statement that may be considered startling, but as my opinion is honest, I am not concerned if it does not agree with the views of others. G.O. Smith and Woodward were both great players, but the Tottenham and Chelsea forward was the better. Why was he the better footballer? Woodward was the more versatile, the more consistent, and cleverer with his heading.

Woodward, who was an architect and surveyor, was a strong-looking young man of twenty-three when he came out with Tottenham Hotspurs. Very nearly 5 ft. 11 in., he weighed at that time 11 st. I rather fear that the strenuous game he played took a lot of vitality out of him. Strenuous is used in the sense of sapping his own strength rather than in applying it outwardly to his opponents.

Force was never his motto. A man who had perfect control of the ball with either foot, he was a wonderful judge of the moment to make the pass to a chum who would foresee where Woodward would next be for the return pass. His adroitness with either the inside or outside of his foot was only equalled by the accuracy of his heading.

With the exception of Alec Turnbull ("Sandy"), of Manchester, and Dean, of Everton, in these latter days, Woodward was as dangerous near goal with his head as any man I have seen. And it should be remembered that Woodward - they called him "Jack" - was faster than he looked, and that he had a neat trick of feinting, or what some call "selling the dummy." The most unselfish of forwards, he was a master-model of team work. He must have scored hundreds of goals.

In the 23 matches of this South African tour in 1910, he was the chief scorer with 32 goals, but there were others who distinguished themselves.

Now let me say that Woodward was soft-spoken, courteous, modest; he never talked about his football, and seldom discussed that of his mates. If he could not speak well of a man he preferred silence. He was devoted to his mother, whom he often took to matches, and did not leave her until she was comfortably seated.

In many respects he was a man who stood alone, combining unsuspected strength of mind and body with a suavity of manner. His personality and play left an abiding impression on the football of South Africa, and there have been not a few who have talked about the seed that was sown by Woodward. The boys, especially those at school, watched him closely.

The harvest was gathered some fourteen years after, in 1924, when South Africa sent a team of amateurs to England. Well they played, for our elevens, representing the strength of English amateurism, could only win the international contests at Southampton and Tottenham by 3-2. I am not so sure that the F.A. side ought to have won at Tottenham. A draw would have more justly reflected the merits of the teams.

Woodward was never a man who lived out of the game. He lived for the game, although he also played cricket. The Football Association found it difficult to get a bill of expenses from him. When the European war broke out he was one of the first to join the Football Battalion of the 17th Middlesex. He was, too, one of the first casualties, but he survived, attained the rank of major, and afterwards devoted himself to farming in Essex, a county that he knew well in his early days.

(6) The Times (23rd March, 1907)

The England selection committee have not yet succeeded in finding a satisfactory set of forwards, the want of a really competent centre forward being the great difficulty. There is always V.J. Woodward to fall back upon; but there is no denying that he has lost a little of his pace, and is more easily knocked off the ball than was the case last year - as a result, it may well be, of the drastic treatment which has been meted out to him by unscrupulous defenders in the rough-and-tumble of Southern League football.

(7) Chelsea programme (27th November, 1909)

We have had so much bad luck of late that, when a genuine piece of the right stuff comes along, we may be pardoned for sitting down and making a proper meal of it. The Bradford result was about the climax of trouble and, we had just got out our miserable looks and our "humpy" speeches when suddenly something occurred to lift us out of the doldrums. There was many a glad smile round the regions of Stamford Bridge when it was announced that Vivian J. Woodward had thrown in his lot with the Chelsea Club.

Possibly Chelsea never have had such a slice of luck. I should say that without a doubt Vivian Woodward is the most popular man in football today. Popular with players, Popular with the spectators wherever and whenever he plays, he owes his unique position chiefly to one thing. First, foremost, and all the time he is a gentleman. He may play well or he may play moderately (he never plays badly), but no matter how he plays his very presence in a team is ever a great factor Of success. He inspires his men with his unflagging energy. He inspires a confidence in them as no other player could ever do. I do not think that there is any doubt that Vivian Woodward was mainly responsible for Tottenham Hotspur's sensational rise to the First Division.

(8) The Sporting Chronicle (30th November, 1909)

The most cheering news we have had during our time of desolation is the intimation that Vivian John Woodward is going to assist Chelsea. Had the great Vivian been a professional player his transfer fee, I fancy, would have been something near a record one. Instead Woodward comes to us for love, and we may take it that he is already the idol of Stamford Bridge. Vivian Woodward always has been and ever will be the people's favourite. Small wonder. Great as he is as a player, his first claim to popularity lies in the fact that he has ever been first and foremost a gentleman. I question if any footballer has ever been so universally popular, and he carries his honours with the air of a bashful debutant. Honours have been showered upon him, and never has he been known, either on or off the field, to belie his title of the perfect gentleman.

(9) East Essex Gazette (February, 1954)

A supreme soccer artist, Woodward fascinated crowds with his magnificent ball control. His biggest personal triumph in Essex was when he beat Harwich & Parkeston "off his own bat", while playing for Chelmsford at Colchester in the Essex Senior Cup. That day he scored three goals, and had a hand in the fourth, Harwich losing, 4-1.

An amateur through and through, Woodward had only one word for the modern soar in transfer fees. "Shocking!" was his comment. That was a remark which those who knew him would expect him to make.

Woodward was considered to be the finest centre forward ever to play for England. Which, when it is considered that he succeeded the great G.O. Smith - is remarkable.

(10) Charlie Buchan, A Lifetime in Football (1955)

On our side at inside-left was the immaculate amateur Vivian J. Woodward. It was the first time I had figured in the same team with this great sportsman and brilliant player.

Woodward, rather frailly built though above average height, could play anywhere in the three inside-forward positions. He was the perfect example of a "two-footed" player.

Rarely have I seen another forward do so much with so little apparent effort. He made the ball do the work, opening up the play and finding his colleagues with beautifully-timed passes.He seemed to stroll through the game yet was seldom out of position. He did his best to make the game easy for those who were playing around him. I could not tell, really, if he were fast or not. He seemed to have no concern with speed.

(11) Norman Jacobs, Vivian Woodward: Football's Gentleman (2005)

With the coming of the depression at the end of the 1920s and into the 1930s, life proved to be a bit more difficult for him but he battled through without complaining - as was his nature - and when the Second World War broke out, he once again answered his country's call by becoming an APP warden.

Towards the end of 1949, Woodward became very ill, suffering from nervous exhaustion. He was no longer able to carry on farming or running his business and he was moved into a nursing home in Castlebar Road, Ealing, Middlesex, under the care of a committee set up by the Football Association. As if it wasn't bad enough that he was suffering from nervous exhaustion and stuck in a nursing home, he had a very unfortunate experience in 1950, when Andrew Ralston,a divisional representative of the council of the Football Association, died suddenly at his bedside while visiting him.

Some time after this, in 1953, he was visited by sports journalist and writer, Bruce Harris. He had been told that Woodward was in the nursing home by Mr J.R. Baxter, a former member of the Footballers' Regiment who had served under Captain Woodward and was now a London Transport bus driver. Together the two men went to see Mr Baxter's former commanding officer. The following is Harris's account of the visit:

"We found Woodward bedridden, paralysed, infirm beyond his seventy-four years, well looked after materially. The Football Association and his two former clubs are good to him; relatives visit him often. "But", he told me in halting speech, "no one who used to be with me in football has been to see me for two years. They never come - I wish they would."The FA sent along a television set. It is little use to him, I fear, in his weak health. He gets more from the sound radio at the bedside. He has trouble in reading but can listen now and then. Woodward's heyday as a footballer fell between the century's opening and the 1914-18 war. Then lie joined up in the Middlesex Regiment, which according to Mr Baxter had "internationals in every platoon". Woodward, wounded in France, took to farming in Essex after the war, was hit by the depression, failed in health and now, in the twilight of his life lacks the company of his own sporting kind in a room lie cannot leave.

(12) Evening News (February, 1954)

Vivian J. Woodward, one of the greatest centre forwards England ever had, died last night, aged seventy-four, at a nursing home at Ealing. He had been ill for four years.

Woodward had a most illustrious career. He was a director of Tottenham Hotspur as well as their centre forward. He was also a director of Chelsea during the time he played for that club.

For many years he was England's centre forward or inside right and, including his amateur and Olympic Games honours, played for England more often than any other player.

He was an out-and-out amateur. Directors of the Spurs and Chelsea have told me they could not get him to charge his bus fares for matches.

He played entirely for his love of the game, and under a code which nowadays would be thought not to belong to this world.

(13) The Times (February, 1954)

Mr Vivian Woodward was to many of my generation the greatest footballer they ever saw, and the living embodiment of the finest spirit of the game. His brilliant play and his outstanding leadership of the victorious British team in the Olympic Games at Stockholm in 1912 will never be forgotten by those who were there; he did much to form the splendid tradition of clean play and sportsmanship which has endured in the Olympic competition ever since.