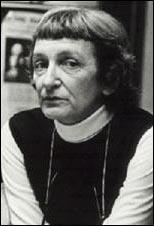

Anne Braden

Anne Gambrell McCarty, the daughter of a salesman, was born in Louisville, Kentucky, on 28th July, 1924. Anne grew up in Anniston, Alabama, where his father's took the family. The household was traditional, middle-class and thoroughly invested in the status quo. "The parents were so much like your average white Southerner of that generation. They were just very accepting of Southern racial politics." (1)

Anne later recalled: "The white southern mentality was literally a Nazi, fascist sort of thing. The attitudes of people I grew up with were not just that Blacks were inferior. To them, the South was the last haven of pure Anglo-Saxon culture, and the rest of the country was corrupted by all sorts of impure strains. New York was so bad because it was filled with a lower breed of humanity from southern Europe. It was agonizing to me when I had to face how wrong all this was. I thought of the people I grew up with as good people - and they were good people in so many ways. But their lives were distorted by the racism they absorbed from the cradle. It seemed tragic to me then and still does." (2)

As a child Anne began to question the racism that existed in Alabama: "As a child, she was moved by Christian teachings of universal brotherhood and sisterhood and of loving one’s neighbor. In her church hung an image of Jesus, surrounded by all the children of the world, of all colors, learning his teachings together. The image stood out to the young Anne because in her experience, children of different colors did not learn together or go to church together. The world that she lived in didn’t seem to match up with Jesus’s teachings." (3)

A Political Education

In 1954, Anne earned a bachelor's degree in English from Randolph-Macon Woman's College in Lynchburg, Virginia. (4) While at college became the editor in chief of the college newspaper, writing about her great passion for moral ideals. It was at Randolph-Macon that "Anne discovered her first female mentors… women who served as role models and who helped Anne expand her vision of her own possibilities as a woman. Anne had grown up in a society where the roles of women were profoundly limited, and where life was even further restricted by notions of individualism that reduced the purpose of life to personal success. The female professors Anne was drawn to, however, emphasized that life was just as much about building stronger communities, and ultimately a better world. Personal happiness was found not through individualistic pursuits, but through contributing to the world and building meaningful connections with others. It was a vision that resonated with Anne, and reminded her of the Christian teachings she felt so compelled by." (5)

A close friend, Harriet Fitzgerald, introduced her to the writings of Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud. Anne believed that the emergence of Adolf Hitler in Nazi Germany and the outbreak of the Second World War increased her opposition to racism: "My college years exactly coincided with World War II. I was part of a generation affected by a spillover of thirties liberalism and a revulsion to the racist philosophy of Nazism during the war. I wasn't that unusual then. Many of my friends in college were not in favor of segregation. We rejected our parents' ideas about race, just as we rejected them about sex." (6)

Carl Braden

After leaving college she became a journalist and eventually she found work with The Louisville Times. There, she met Carl Braden, a fellow reporter who was active in progressive politics. (7) Carl had been born into a struggling working-class family. His father had been a railroad worker and an active trade unionist who had lost his job when Carl was eight years old while involved in a strike demanding better working conditions. "For months afterwards, the family ate almost nothing but beans. One of Carl’s dominant childhood experiences was of hunger – in the deep, psychological sense of not knowing when you would be able to get food to relieve it. For Carl, hunger meant growing up early. He became deeply aware of injustice… of the fact that many people, like his family, worked hard and still had nothing, and yet were harshly judged as poor White trash by families exactly like Anne’s." (8)

Braden parents were Catholics but his father had lost his faith and became an agnostic socialist and insisted that his son was named after Karl Marx. Carl's father was a member of the Socialist Party of America and a follower of Eugene Debs and used to take his son to political meetings. Carl went to a Catholic school, and when he was thirteen the nuns encouraged him to put his intellectual abilities in the service of God and to begin studying to become a priest but left his Roman Catholic seminary in Louisville at the age of 16 to become a newspaper reporter. (9)

Anne married Carl Braden in 1948. She later recalled: "I realized the people I had grown up with - my family, my friends, the people I loved and still love today - were just plain wrong on how they treated Blacks and bettered themselves by taking advantage of them. The hardest thing for any of us to come to grips with is that our own society is wrong because we project our ego onto our society. You really have to turn yourself inside out. But once you can do that, everything begins to fall into place. My personal values changed. Up to then, I'd been very ambitious, wanting to get ahead and be a big reporter. Now I decided I didn't want to work for an establishment paper and just be an observer of life.... Now I wanted to be part of this movement for change. I got head over heels involved, not only in the civil rights movement but in the peace movement." (10)

Henry Wallace and the Progressive Party

Anne and Carl both began supporters of Henry Wallace who had formed the Progressive Citizens of America (PCA). Other members included Rexford Tugwell, Paul Robeson, W.E.B. Du Bois, Arthur Miller, Dashiell Hammett, Helen Keller, Jo Davidson, Thomas Mann, Aaron Copland, Claude Pepper, Eugene O'Neill, Glen H. Taylor, John Abt, Edna Ferber, Thornton Wilder, Carl Van Doren, Fredric March and Gene Kelly. A group of conservatives, including Henry Luce, Clare Booth Luce, Adolf Berle, Lawrence Spivak and Hans von Kaltenborn, sent a cable to Ernest Bevin, the British foreign secretary, that the PCA were only "a small minority of Communists, fellow-travelers and what we call here totalitarian liberals." Winston Churchill agreed and described Wallace and his followers as "crypto-Communists". (11)

Wallace decided to stand in the 1948 Presidential Election. His running-mate was Glen H. Taylor, the left-wing senator for Idaho. The programme of Wallace and Taylor included new civil rights legislation that would give equal opportunities for black Americans in voting, employment and education, repeal of the Taft-Hartley Bill and increased spending on welfare, education, and public works. Their foreign policy program was based on opposition to the Truman Doctrine and the Marshall Plan. Anne and Carl Braden worked for his campaign but Wallace's chances were badly damaged when William Z. Foster, head of the American Communist Party, announced he would be supporting Wallace in the election. (12)

Wallace travelled to the Deep South and called for the end of the Jim Crow laws. He was attacked at every point he stopped and made a speech. One of his followers said: "You can call us black, or you can call us red, but you can't call us yellow." Wallace commented: "To me, fascism is no longer a second-hand experience. No, fascism has become an ugly reality - a reality which I have tasted it neither so fully nor so bitterly as millions of others. But I have tasted it." (13)

Harry S. Truman and his running mate, Alben W. Barkley, polled more than 24 million popular votes and 303 electoral votes. His Republican Party opponents, Thomas Dewey and Earl Warren, won 22 million popular votes and 189 electoral votes. Storm Thurmond ran third, with 1,169,032 popular and 39 electoral votes. Wallace was last with 1,157,063 votes. Nationally he got only 2.38 per cent of the total vote. Only one supporter, Vito Marcantonio, won his seat in Congress.

Andrew Wade Case

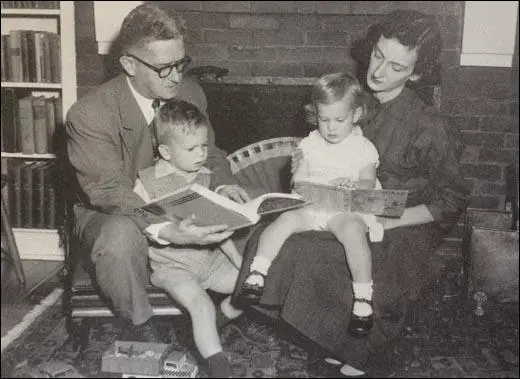

Carl Braden began work Louisville Courier-Journal whereas Anne Braden gave up work to raise her three children, James, Elizabeth and Anita. She was also an active member of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). In 1954 the Bradens became involved in helping Andrew Wade, an electrician, in buying a house. "Carl and I were both part of a statewide committee to repeal the Kentucky school segregation law. We were also involved in trying to break down discrimination in hospitals. In the spring of 1954, a Black friend, Andrew Wade, asked us if we would buy a house and transfer it to him. He and his wife had one child, two and a half years old, and another on the way. They were crowded into a small apartment and were anxious to move out of the city. Andrew had tried, but as soon as sellers found out he was Black, he wouldn't get the house. He decided the only way left was to have a white person buy it for him. Before he came to us, he had asked several others. For one reason or another, they refused. But we felt he had a right to a new house and never thought twice about doing it." (14)

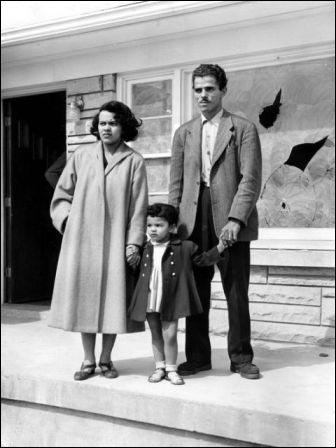

Andrew, his pregnant wife, Charlotte and their 2-year-old daughter Rosemary - moved into their new home at 4010 Rone Court, Louiseville. Anne Braden later recalled: "That night, they heard gunshots, and somebody was firing at the house, and Andrew says he told his wife to get down, but it didn’t hit anybody. And they looked out and there was a cross burning in the field next to them.” In the days that followed "a stone bearing a racial epithet hurled into a window, the local dairy refused to deliver milk; the Wades’ newspaper subscription canceled because the carrier wouldn’t deliver it." (15)

home in Shively the day after someone hurled a a rock through the front window.

Anne Braden explained: "A Wade Defense Committee was formed that had strong support in the Black community, but not a lot of whites. We got the police to put up a guard, which we never trusted. Some people volunteered to stay all night to help the Wades to keep watch.." (16) One of the guards was Lewis Lubka. “I was in the back kitchen with a gun. And when we were shot at we shot back. I was working days and helping guard the house at nights.” (17)

Millard Grubbs, a member of the Ku Klux Klan, who lived in Alabama, wrote to the local newspaper, Shively Newsweek, claiming that the Wade purchase as a "Communist conspiracy" to establish "a black beach-head in every white sub-division". He argued that segregation had been ordained by God and condemning the Marxist world plotters" who would undermine it. He went on to say that Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman and Dwight D. Eisenhower were involved in this conspiracy and that to challenge segregation was part of a "rising red bureaucracy". He ended his letter by inviting "loyal white people" to join his newly formed American White Brotherhood. (18)

The night of June 27, 1954, a bomb went off under Rosemary's room, causing $7,000 worth of damages to the property. Luckily, she had gone to spend the night with her grandmother. (19) The Louisville Police Chief Carl E. Heustis told Carl Braden that he had a confession from the man (a former policeman) who set the dynamite and there'd be an arrest in a few days. (20) Although the people responsible, the same who had participated in the cross burning just weeks earlier, were identified, they were neither arrested or indicted for the crime. (21)

On 16th September, the state prosecutor made a statement that there were two theories about the bombing. As Anne Braden explained: "One was that the neighbors blew it up to get the Wades out of the area. The other was that it was a Communist plot to stir up trouble between the races and bring about the overthrow of the governments of Kentucky and the United States. The prosecutor was developing the theory that Wade would never have thought of moving there on his own, because Black people are really happy with things as they are until white radicals stir them up." (22)

On 1st October, 1954, instead of the grand jury producing indictments against the people who blew up the house, those white people who had been supportive of the Wades were charged with sedition. This included Anne and Carl Braden, Vernon Bown, Louise Gilbert, LaRue Spiker, Lew Lubka and I. O. Ford. Bown, a young white man who stayed with Charlotte Wade during the day while Andrew Wade was at work, was charged with the dynamiting of the house. (23) Amber Duke has argued that the only way this can be explained is that this was at the time of McCarthyism and anti-Communist hysteria. (24)

Anne recalled: "They raided our house and took all of our files. We'd been in touch with many different groups, and we had folders on left-wing organizations. They took a lot of our books. Carl had grown up in a socialist home, and he had a Marxist and left-wing library. They took anything with a Russian name: books by Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, and Turgenev from a Russian literature course I had in college. The commonwealth detective who went through them testified that he didn't really know too much about books. When he was in school, he said, they made him read, and it turned him against books, and he hadn't read much since." (25)

The Bradens became victims of what became known as McCarthyism. On 9th February, 1950, Joseph McCarthy, a senator from Wisconsin, made a speech claiming to have a list of 205 people in the State Department that were known to be members of the American Communist Party (later he reduced this figure to 57). The list of names was not a secret and had been in fact published by the Secretary of State in 1946. These people had been identified during a preliminary screening of 3,000 federal employees. Some had been communists but others had been fascists, alcoholics and sexual deviants. If screened, McCarthy's own drink problems and sexual preferences would have resulted in him being put on the list. (26)

For the next two years McCarthy's Senate committee investigated various government departments and questioned a large number of people about their political past. Some lost their jobs after they admitted they had been members of the Communist Party. McCarthy made it clear to the witnesses that the only way of showing that they had abandoned their left-wing views was by naming other members of the party. This witch-hunt and anti-communist hysteria became known as McCarthyism. (27)

Lynn Burnett has argued: "During the period of McCarthyism, right-wing forces exploited the growing tensions between the Soviet Union and the United States that developed in the wake of the Second World War. They used those tensions to whip the American public into a state of fear: Communism, they said, would spread rapidly across the globe unless severe measures were taken. They warned that Communists had already infiltrated deep into American society, and were working with the Soviet Union to undermine the United States from the inside. After using this wildly unsubstantiated myth to whip the public into a state of fear, these forces then used that fear as an excuse to destroy causes they opposed – including civil rights and organized labor – under the pretense that such causes were Communistic. It was easy to manufacture the connection because Communists were, indeed, major supporters of racial justice and labor rights. Because Communists were highly involved in those causes, anyone devoted to those causes would have worked around and known Communists themselves. In the period of McCarthyism, anyone who was around Communists was framed as a Communist sympathizer, which was then equated with being an enemy of the state. This is what was now happening to Anne and Carl Braden." (28)

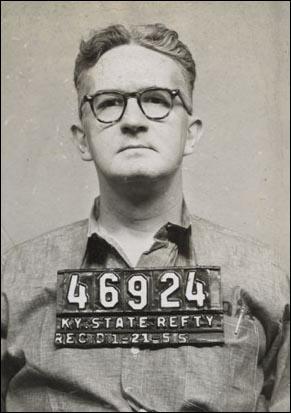

The defendants asked for and were granted separate trials. The state insisted that Carl Braden, the perceived ringleader face trial of the initial sedition charge. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) provided Louis Lusky as his defence attorney and he faced an all-white jury. The state provided nine former American Communist Party. members, now paid FBI informants. "Their testimonies were largely biographical, detailing the evils of communism in their own lives and asserting that the CP-USA was an organization bent on the overthrow of the USA government." (29)

Prosecuting attorney, Scott Hamilton contended that the dynamiting of the Wade house was a Communist plot to excite racial hatred. He told the jury: "Sedition is communism and communism is sedition - there is no distinction." The defence on the other hand, argued that the prosecution was trying to get the jury to "say something the law doesn't say". Braden's attorney said the issue was simply "whether or not a man has the right to an opinion different from those in the community." (30)

Anne pointed out: "Carl was tried first. It was December... Every once in a while, they'd imply that we blew up the house, that Vernon Bown's radio was used to set off the dynamite. They introduced our books; tables of them were on trial. But the main testimony came from nine "expert" witnesses, gotten from the House Un-American Activities Committee. They were there to create atmosphere. None of them claimed to know Carl, but they testified that anybody who read those books was probably a Communist. They said that the purchase and resale of the Wade house fit in with the Communist program for the South, of taking land away from white people and giving it to Black people. They actually got on the witness stand and said that." (31)

Carl Braden was found guilty of sedition. His punishment was fixed at fifteen years' imprisonment and a $5,000 fine. His employer, the Louisville Courier-Journal, immediately issued a statement saying it had dismissed Braden: "This newspaper has gone on the time-honored principles, rooted in our American Constitution, that a man is innocent until proved guilty. Since Braden was charged by the grand jury on October 1st, he has performed no work for this organization. His conviction now puts a permanent end to his connection with the Courier-Journal." (32)

Anne Braden's trial was due to start on 14th February, but then it got postponed to the 28th, and then again and again until April, when they agreed to put off all the Wade trials until the higher courts ruled on Carl's case. At the time several civil rights activists had been sent to prison for sedition. This included Steve Nelson in Pennsylvania, who been charged under the 1919 Pennsylvania Sedition Act for attempting to overthrow the state and federal government. Unable to use wiretap evidence the prosecution was forced to rely on the testimony of FBI informant Matt Cvetic. Nelson was convicted, fined $10,000 and sentenced to 20 years in prison. Concurrent with the Pennsylvania Sedition case, Nelson and five co-defendants were indicted in 1953 under the Smith Act. All six men were found guilty and each sentenced to 5 years and fined $10,000. (33)

Steve Nelson argued his case in the publication of The Thirteenth Juror (1955). His lawyers argued that the testimony of Matt Cvetic was deeply flawed. Daniel J. Leab, the author of I Was a Communist for the FBI: The Unhappy Life and Times of Matt Cvetic (2000) that by 1955 Cvetic had been largely discredited as a witness and the Justice Department's Committee on Security Witnesses unanimously recommended that he not be used as a witness unless his testimony could be corroborated by external sources." (34)

In 1956 in Pennsylvania v. Nelson, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the 1919 Pennsylvania Sedition Act. The court ruled that the enactment of the Smith Act superseded the enforceability of the Pennsylvania Sedition Act and all similar state laws. In the same year the Supreme Court granted Nelson and the other five defendants in the Smith Act case a new trial on the grounds that testimony had been perjured in the earlier case. By the beginning of 1957 the Government decided to drop all charges, bringing six years of legal battles to an end. (35)

Anne Braden pointed out that their case had influenced the decision of the Supreme Court. "They saw it as a horrible example of what happens when you turn every local prosecutor loose with a state sedition law." The state prosecutor dropped all sedition charges against Anne and her co-defendants but it was not until 1956 that they overturned Carl Braden's conviction. (36) The Wade family attempted to repair their home, but amid continuing hostility, sold the house at a loss and moved back into west Louisville. (37)

Anne Braden - Civil Rights Activist

Anne and Carl could not, however, return to their old lives. In order to stay safe and be in a supportive environment, they moved into a Black neighborhood, where their children wouldn’t have to see their parents being constantly ostracized. In 1957, the Bradens joined the Southern Conference Education Fund (SCEF), an organization dedicated to building White southern support for integration, and had thrown their full support behind the Bradens during their sedition trial. Its monthly newsletter, the Southern Patriot, was produced for the supporters of civil rights across the nation. During Carl’s incarceration, the Patriot had published articles by Anne and had helped her gain a national audience. The executive director of the SCEF was Jim Dombrowski and its vice president was Modjeska Simpkins. (38)

Anne recalled: "Jim Dombrowski, the architect of the ongoing SCEF, was one of the greatest people who ever lived in the South. He was a founder, with Myles Horton and Don West, of Highlander Folk School. He's been involved in various struggles for social justice since the early 1930s. He saw the need for a group of Blacks and whites working together with a one-point program: End segregation in the South... In 1957 Carl and I went to work for SCEF. They didn't have much money, so we worked for practically nothing at first. Our main job was to reach white people and help them see that civil rights was their battle, too. We didn't have many resources, and we were fighting against a lot of fear. We traveled around, linking up with college professors, students, teachers, professional people, and ministers - many of whom lost their churches when they took a stand for equal rights." (39)

The SCEF worked closely with other civil rights organizations such as Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). She also became friends with Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks. Another close associate was Virginia Durr, a White Southern aristocrat whose husband, Clifford Durr, had worked for Franklin D. Roosevelt during the New Deal. Writing to a friend in 1959, Virginia said, “I have made a new friend, Anne Braden… Who sees life in Alabama as I do, but with even deeper insight, much deeper I think. She is a lovely and charming and gentle person with a brilliant mind and is such a comfort to me.” A few months later, she wrote: “Anne Braden has been here recently and she is a perfect darling and I love her and I think she is a very good writer too. After she was gone, the Attorney General came out with a huge warning to all the people of Alabama to beware of her as she was so dangerous.” (40)

In 1958 the House Committee on UnAmerican Activities (HUAC) announced it wanted to investigate left-wing activists in the Deep South. The SCEF produced a letter signed by 200 Black leaders that in essence said: "We've got enough problems down here. Our churches are being bombed. Our kids are being attacked as they go to school. The last thing we need is the House Un-American Activities Committee coming here to attack white people who are supporting justice." (41)

Carl Braden was indicted in 1958 for contempt of Congress after refusing on First Amendment grounds to testify before the HUAC. He stated "My beliefs and my associations are none of the business of this Committee." Braden's conviction was upheld 5-4 in the Supreme Court in 1961 and he went to prison but was released early in 1962. (42)

The Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham was used as a meeting-place for civil rights leaders such as Martin Luther King, Ralph David Abernathy and Fred Shutterworth. Tensions became high when the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) became involved in a campaign to register African American to vote in Birmingham.

On Sunday, 15th September, 1963, a white man was seen getting out of a white and turquoise Chevrolet car and placing a box under the steps of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. Soon afterwards, at 10.22 a.m., the bomb exploded killing Denise McNair (11), Addie Mae Collins (14), Carole Robertson (14) and Cynthia Wesley (14). The four girls had been attending Sunday school classes at the church. Twenty-three other people were also hurt by the blast. The bombing was the fourth in less than a month, and fiftieth in two decades, in what had become known as "Bombingham." (43)

Diane Nash and her husband, James Bevel, in response to the bombing, became committed to raising a nonviolent army in Alabama. Its main objective was obtaining the vote for every black adult in the state. Alabama and other southern states had effectively excluded blacks from the political system since disenfranchising them at the turn of the century. In 1962, Deputy Attorney General Burke Marshall reported that “racial denials of the right to vote” existed in eight states, with only fourteen percent of eligible black citizens registered to vote in Alabama. In Mississippi, 42% of the population were black but only 2% were registered to vote. (44)

This eventually became known as the Selma Voting Rights Campaign. Nash told Martin Luther King: "He (King) could notorious a battered people for nonviolent action and then give them nothing to do. After the church bombing, she and Bevel had realized that a crime so heinous pushed even nonviolent zealots like themselves to the edge of murder. They resolved to do one of two things; solve the crime and kill the bombers, or drive (Governor George Wallace and Police Chief Albert J. Lingo) from office by winning the right for Negroes to vote across Alabama." (45)

Diane Nash attracted the attention of President John F. Kennedy, who selected her to serve on a committee to develop a national civil rights platform, which later became the 1964 Civil Rights Act. The next year, Nash planned marches from Selma to Montgomery to support voting rights for African Americans in Alabama. Anne and Carl Braden took part in the march. When the peaceful protesters tried to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge to head to Montgomery, police severely beat them. Stunned by images of law enforcement agents brutalizing the marchers, Congress passed the 1965 Voting Rights Act. (46)

Carl Braden the executive director of the Southern Conference Education Fund, became the leader of the Training Institute for Propaganda and Organizing in Louisville, Kentucky in 1971. However, he died of a heart attack in Louisville on 18th February, 1975. He was 60 years old. (47)

Anne Braden continued to be active in the civil rights movement. Suzy Post was one of those who worked closely with her: “She (Anne Braden) was a fascinating woman and she did fascinating things. Louis (Coleman) worked with her, hand in glove. He was a staff person for the Louisville Urban League at the time that Anne was out there fomenting rebellion. She was very dour. Any white person who wasn’t working for social justice, she wanted to make feel guilty. She was very Christian in her approach to it. I mean, she thought if you weren’t working actively for social justice for people of color, you were against it. She took a very it’s-all-black-or-it’s-all-white point of view, and she had no sense of humor. None.” (48)

David J. Leonard has commented: "Braden was committed to and involved in a myriad of movements, fighting against economic injustice, environmental injustice, war, classism, racism, and sexism. Where there was violence and degradation, Anne Braden was likely fighting alongside countless others... Her ethics and ethos, a willingness to confront injustice whereever it confronted her... Braden expresses a level of fearlessness that spit in the face of white supremacy, patriarchy, and class inequality. She was always standing in opposition to white supremacy, on the other side of the police state, yet the danger and the consequences never led her to shy away from a fight." (49)

In an interview she gave just before her death, Anne Braden said: "When you get involved in trying to change society, the people who run things don't just let you do it without hitting back in some way. That's a given. There's always the temptation, when things get rough, to withdraw. And to a certain extent, we whites usually can. I was lucky, in a way, that I never had to withstand that temptation. After the sedition case, life burned my bridges behind me. And looking back on it, I'm glad it did." (50)

Anne Braden died, age 81, in Louisville on 6th March, 2006.

Primary Sources

(1) Anne Braden, interviewed in Bob Schultz & Ruth Schultz, The Price of Dissent: Testimonies to Political Repression in America (2001)

I born in Kentucky, a descendant of the first white child born there - white as compared to Indian. My family saw it as a mark of distinction. The white southern mentality was literally a Nazi, fascist sort of thing. The attitudes of people I grew up with were not just that Blacks were inferior. To them, the South was the last haven of pure Anglo-Saxon culture, and the rest of the country was corrupted by all sorts of impure strains. New York was so bad because it was filled with a lower breed of humanity from southern Europe.

It was agonizing to me when I had to face how wrong all this was. I thought of the people I grew up with as good people - and they were good people in so many ways. But their lives were distorted by the racism they absorbed from the cradle. It seemed tragic to me then and still does....

My college years exactly coincided with World War II. I was part of a generation affected by a spillover of thirties liberalism and a revulsion to the racist philosophy of Nazism during the war. I wasn't that unusual then. Many of my friends in college were not in favor of segregation. We rejected our parents' ideas about race, just as we rejected them about sex. But I don't think any of the people I went to college with ended up getting thrown in jail for sedition by the time they were thirty. And what makes the difference, what makes some get involved while others fade back into the scenery - which is what most people did - is accident. I think it's who you meet in certain times of your life, what your experiences are...

I realized the people I had grown up with - my family, my friends, the people I loved and still love today - were just plain wrong on how they treated Blacks and bettered themselves by taking advantage of them. The hardest thing for any of us to come to grips with is that our own society is wrong because we project our ego onto our society. You really have to turn yourself inside out. But once you can do that, everything begins to fall into place. My personal values changed. Up to then, I'd been very ambitious, wanting to get ahead and be a big reporter. Now I decided I didn't want to work for an establishment paper and just be an observer of life.... Now I wanted to be part of this movement for change. I got head over heels involved, not only in the civil rights movement but in the peace movement....

Carl and I were both part of a statewide committee to repeal the Kentucky school segregation law. We were also involved in trying to break down discrimination in hospitals. In the spring of 1954, a Black friend, Andrew Wade, asked us if we would buy a house and transfer it to him. He and his wife had one child, two and a half years old, and another on the way. They were crowded into a small apartment and were anxious to move out of the city. Andrew had tried, but as soon as sellers found out he was Black, he wouldn't get the house. He decided the only way left was to have a white person buy it for him. Before he came to us, he had asked several others. For one reason or another, they refused. But we felt he had a right to a new house and never thought twice about doing it....

A Wade Defense Committee was formed that had strong support in the Black community, but not a lot of whites. We got the police to put up a guard, which we never trusted. Some people volunteered to stay all night to help the Wades to keep watch. By the end of June, just as things seemed to be quieting down, somebody blew up their house. Dynamite was set under their little girl's bedroom. Luckily, she had gone to spend the night with her grandmother. Mr. and Mrs. Wade happened to be talking to a friend on the other side of the house. It was just by the grace of God nobody was killed...

They raided our house and took all of our files. We'd been in touch with many different groups, and we had folders on left-wing organizations. They took a lot of our books. Carl had grown up in a socialist home, and he had a Marxist and left-wing library. They took anything with a Russian name: books by Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, and Turgenev from a Russian literature course I had in college. The commonwealth detective who went through them testified that he didn't really know too much about books. When he was in school, he said, they made him read, and it turned him against books, and he hadn't read much since...

Carl was tried first. It was December... Every once in a while, they'd imply that we blew up the house, that Vernon Bown's radio was used to set off the dynamite. They introduced our books; tables of them were on trial. But the main testimony came from nine "expert" witnesses, gotten from the House Un-American Activities Committee. They were there to create atmosphere. None of them claimed to know Carl, but they testified that anybody who read those books was probably a Communist. They said that the purchase and resale of the Wade house fit in with the Communist program for the South, of taking land away from white people and giving it to Black people. They actually got on the witness stand and said that...

Jim Dombrowski, the architect of the ongoing SCEF, was one of the greatest people who ever lived in the South. He was a founder, with Myles Horton and Don West, of Highlander Folk School. He's been involved in various struggles for social justice since the early 1930s. He saw the need for a group of Blacks and whites working together with a one-point program: End segregation in the South... In 1957 Carl and I went to work for SCEF. They didn't have much money, so we worked for practically nothing at first. Our main job was to reach white people and help them see that civil rights was their battle, too. We didn't have many resources, and we were fighting against a lot of fear. We traveled around, linking up with college professors, students, teachers, professional people, and ministers - many of whom lost their churches when they took a stand for equal rights.

(2) Lynn Burnett, The Life of Anne Braden (28th July, 2019)

Anne Braden is one of the greatest examples we have of a White Southerner, steeped in the culture of segregation, breaking free from that culture and becoming a powerful voice for Black liberation. Born in 1924 and raised in a well-off family in Alabama, Anne questioned segregation as a child and again while in college, before finally making a clean break with White supremacy as a journalist in the mid-1940s. When the civil rights movement broke out a decade later, Anne was one of the few figures that White Southerners could look to as an example of how to liberate themselves from their own oppressive culture and beliefs, and to work for racial justice. Her life, however, has lessons for us all: for we all benefit from understanding how White people can break free from the grip of racism, stand in solidarity with people of all colors, and come together to build a better world.

Like many Southerners, Anne Braden grew up in a deeply religious household. As a child, she was moved by Christian teachings of universal brotherhood and sisterhood and of loving one’s neighbor. In her church hung an image of Jesus, surrounded by all the children of the world, of all colors, learning his teachings together. The image stood out to the young Anne because in her experience, children of different colors did not learn together or go to church together. The world that she lived in didn’t seem to match up with Jesus’s teachings.

Nor did segregation match up with Anne’s sense of fairness as a child. When Anne’s clothes were worn out, her family passed them down to a little Black girl who was bigger than Anne… so the clothes were not only worn out but were too tight. Growing up in a paternalistic culture, the fact that little Black kids were often given the discarded clothes of little White kids was viewed by the adults in Anne’s life as an act of compassion and generosity. But the young Anne viewed it as unfair. She imagined being the little Black girl, and she knew she wouldn’t be happy to have to wear those tight, worn-out clothes. However, when Anne asked questions about the poverty she saw amongst African Americans, the adults in her life told her that Black people were a “simpler race” with fewer needs, and were “happy with the way things were.” Anne, however, could never fully believe this.

Anne would later insist that she was not an exceptional child for questioning segregation. Rather, this process of questioning was a normal part of growing up in the White South. However, in the decades before the civil rights movement forced the conversation, White Southerners rarely discussed segregation: it was simply an accepted fact of life. Those who did dare to question it found themselves marginalized and isolated, or even forced out of the region under threat of violence and economic retaliation. Anne didn’t become aware that people questioned segregation at all until she went to college… an opportunity many White Southerners, and especially White Southern women, did not have. In the White South, with its culture of silence around racial disparity, there were few opportunities for children to explore their concerns about fairness and justice. As they grew up, they usually acclimated into the culture of White supremacy they were raised in. Anne Braden often emphasized that the same would have happened to her had other events in her life not unfolded.

When Anne was a teenager, she began to worry that she was unpopular and unattractive. She realized that boys were often attracted to girls who made them feel like they were the smart ones, and so she began to downplay her intelligence. Indeed, she quickly became popular after making this decision. When the time came to go to college, she still had boys on her mind, and so rejected the idea of going to a women’s college. However, World War II had begun while she was in high school. In 1940 Congress initiated a peacetime draft, and Anne realized that given the likelihood of the U.S. entering the war, that few men would be on campus. She changed her mind and made a decision that would alter the course of her life: she decided to go to a women’s college after all.

In an environment where she didn’t feel the need to downplay her intelligence, Anne was able to find herself. Instead of rejecting her love of learning, she embraced it, later writing that “I don’t think I knew the excitement of an idea until I got to college.” She studied literature and journalism and became the editor in chief of the college newspaper, writing about her great passion for moral ideals and the tremendous struggles against fascism and for democracy happening overseas. Anne won many awards for her work and graduated from Stratford Women’s College as valedictorian.

It was at Stratford that Anne discovered her first female mentors… women who served as role models and who helped Anne expand her vision of her own possibilities as a woman. Anne had grown up in a society where the roles of women were profoundly limited, and where life was even further restricted by notions of individualism that reduced the purpose of life to personal success. The female professors Anne was drawn to, however, emphasized that life was just as much about building stronger communities, and ultimately a better world. Personal happiness was found not through individualistic pursuits, but through contributing to the world and building meaningful connections with others. It was a vision that resonated with Anne, and reminded her of the Christian teachings she felt so compelled by.

Anne had been five years old when the Great Depression began, and although her own father held a steady job and their family was economically secure, she had strong memories of endless streams of beggars getting off the trains going door-to-door begging. She was also aware, as a child, that African Americans rode these trains as well, but never dared to beg in White neighborhoods. As a teenager, she understood the rising threats of fascism overseas; of global destabilization; and finally of world war. The notion of a life devoted to something larger than ones own self spoke to Anne’s religious sensibilities, but it seemed especially important given the dire times Anne was living through. She was drawn to these professors, and they took her under their wings. One of them began inviting Anne to intellectual gatherings, where Anne was introduced to the professor’s sister, Harriet Fitzgerald. Harriet became the first person Anne Braden met who did not merely disagree with segregation, but took an active stance against it.

Harriet had a female lover in New York, and may have had romantic feelings for Anne as well. She made a special effort to help Anne cultivate herself as an intellectual – introducing her to the works of influential thinkers of the era, including Freud and Marx – and sought to help Anne overcome the prejudices she was raised with. Although Anne did not share Harriet’s romantic desires for women, she was able to experience a deep emotional support from Harriet that made all of her previous experiences with men seem superficial. Anne described their connection as a kind of intense intellectual excitement she had not yet experienced, later expressing that “before I met Harriet, I never knew that kind of excitement was possible between two human beings. Later I told her that I didn’t think I would have ever been able to have the kind of relationship I had with Carl [her future husband] had it not been for her. Never after that have I felt any sexual interest in someone who did not excite me intellectually.”

Anne had a major racial awakening when she went to visit Harriet in New York. Harriet – hoping to help Anne break free from her segregationist upbringing – arranged for her to have dinner with a Black woman from the South, under the pretense that they had similar intellectual interests. Anne later wrote: “I went to the meeting with some misgivings. Never in my life had I eaten with a Negro.” Anne later realized that the woman was well aware of how she would have felt as a White woman from the South, and was consciously trying to put Anne at ease. The Black woman was, essentially, working with Harriet to help Anne process, work through, and eventually break free from her White supremacist upbringing.

The two women soon fell into deep conversation… and once they did, Anne ceased to think about the fact that she was White and her conversationalist was Black. They were simply two people having an excellent conversation. Suddenly, in the middle of the conversation, Anne became aware of the fact that she had forgotten about race entirely. A shockwave rippled through her: there was no actual “race problem!” It was an illusion. She later wrote that at this moment, “some heavy shackles seemed to fall from my feet.” The chains that prevented her from being able to embody the spiritual visions she was drawn to as a child – of loving one’s neighbor as oneself; as striving for universal sisterhood and brotherhood – were starting to break.

By this time, Anne had transferred to Randolph-Macon Women’s College – a larger school, where she would be even more intellectually challenged. Here, she studied dance, became aware of the deep connections between her physical, mental, and spiritual health, and fell in love with the Russian authors Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky. She began running with an “artsy” crowd, and amongst this crowd – many of whom consciously thought of themselves as outsiders – it was common to oppose segregation. Anne’s conversation in New York, combined with her participation in this crowd, led her, for the first time, to develop a conscious stance against segregation. A third and final element in the development of that consciousness during her college years was World War II: as Anne later wrote, “We were aware that in fighting Hitler, we were fighting a racist ideology, though I don’t think we used that word ‘racist.’ It didn’t escape people I knew that those ideas about racial superiority were akin to what we had here in the South.”

By the time Anne graduated from college in 1945 – shortly before the end of the war – she had developed an anti-racist consciousness. However, she had not yet acted on that consciousness, nor did she know how too. She had yet to meet people who were engaged in actual struggle, and was not even aware that major struggles against racial oppression were sparking up all over the South. All of this would soon change.

Following her graduation, Anne returned home to live with her parents and became a full time reporter examining local political issues. When fascism was finally defeated overseas, a sense of euphoria swept through her: democratic ideals had won the day! Authoritarianism had been defeated! However, as Black GI’s returned from the war, they made it clear that they had not fought and died overseas fighting Hitler’s racist authoritarianism, only to return home and be subjected to the racist authoritarianism of Jim Crow. They would not rest until democracy was extended to their people as well. Lynchings skyrocketed as Black men in uniform fought for the basic rights to democracy for Black Americans. As a reporter who had to chronicle these events, Anne’s euphoria about the success of democracy quickly faded.

She sank into depression. Without her college community and her easy access to professors and mentors, Anne didn’t know where to turn. Her concerns could not easily – or even safely – be discussed. Like many White Southerners who were troubled by segregation, Anne felt alone. Not yet aware of the communities and organizations that embodied her newly found anti-racist values, she turned inwards. Without community, she threw herself into work and into writing… but also into isolation.

It did not help that she was back home. As African Americans increasingly stood up for their rights after the war, many White Southerners reacted by taking increasingly stronger stances for keeping things the way they were. Anne’s father was one of those people. Both of her parents were deeply disturbed by Anne’s newfound anti-racist perspectives, and her father expressed that he regretted ever sending her to college. During one of their many arguments, Anne expressed that she supported a federal anti-lynching law. Her father exploded: “We ought to have a good lynching every once and a while to keep the N****** in his place!” Although he later regretted saying it, the outburst shook Anne to her core. She had always seen her father as a gentle and loving man, and she felt confident that he would never actually join a lynch mob. Still, here was an otherwise good-hearted man who had justified murder in his own heart and mind. It was one of the key moments in Anne’s life that caused her to think of White supremacy as something that distorted the souls of White people; that caused them to act against the spiritual and ethical values they believed in, and that made it impossible for them to live out truly ethical or spiritual lives. White supremacy, for Anne, became something that White people needed to free themselves from.

Anne escaped the tensions of her home by taking a job in Birmingham in the summer of 1946, reporting on the events at the courthouse. Bull Connor – who would later go down in history for ordering fire-hoses and attack dogs to be turned on civil rights protestors in 1963 – was the police commissioner. Well known for his brutality, Connor’s police forces had recently murdered five Black veterans who had dared to stand up for their rights after returning from war. Anne witnessed Black veterans lined up at the courthouse, trying to register to vote. The same men came week after week, without success. She wanted to write an article about these voter registration attempts, but the newspaper didn’t consider it worth reporting on.

As Anne covered the events at the courthouse, she was forced to realize that there was not one legal system, but two. There, she saw that if a Black man killed a White man, the outcome for the Black man – no matter what the circumstances, such as clear cases of self-defense – would be execution. On the other hand, she saw that if a White man killed a Black man, the judge would almost always rule that the killing had been justified. She saw that if a White man raped a Black woman, the case was simply dismissed: it was not even worth discussion. But if a Black man so much as looked at a White woman in an “improper” way, it was usually ruled as “assault with intent to rape.” Braden reported on one case in which a Black man was charged with “assault with intent to rape,” when he had looked at a White woman in an “insulting way” from across the street. It would be nearly a decade until the case of Emmett Till – murdered for whistling at a White woman in the summer of 1955 – brought such injustices before the eyes of the nation, and helped to ignite the civil rights movement.

One day, a deputy at the courthouse began flirting with Anne. Hoping to impress her, he opened a cabinet drawer and pulled out the skull of a Black man who – he hinted, with a proud gleam in his eye – he had helped kill. He told her that the murder would, of course, never be solved. Anne later wrote: “I looked at the skull. It became larger before my eyes. It filled the room and the world. It became a symbol of the death that gripped the South.” The death – the murder – that her own, loving father supported. Anne was filled with horror and rushed out of the room. The violence against Black people in the Deep South was so casual it was usually not even deemed worthy of reporting or discussing, but now Anne found herself facing it fully. It was too much for her. After eight months of facing brutal truths in Birmingham, she took another newspaper job in the Upper South: in Louisville, Kentucky, where she had been born before moving to the Deep South as a baby. It would be in Louisville that she encountered civil rights activists for the first time, and met people who helped pull her into the movement.

When Anne first arrived in Louisville, she felt a great sense of relief at the absence of brutality that she perceived. Unlike the constant, casual violence of the Deep South, there had been no outright racial violence in Louisville for a long time. The buses were not segregated. African Americans could vote, which meant that there were politicians who actually represented Black interests. Unlike in the Deep South, Black issues were not made invisible to the White community, but were actually reported on. There were even White people who openly opposed racial oppression. However, most spaces were still segregated, including parks, hotels, restaurants, theatres, hospitals, and schools. And as was true throughout the country, African Americans were restricted to living in impoverished neighborhoods, and suffered from rampant job discrimination. However, the mere fact that there was any degree of desegregation and any degree of Black political power was what initially jumped out at Anne.

On her first day of work at the Louisville Times – March 31, 1947 – Anne was introduced to her new colleagues… including the man who would become her future husband, Carl Braden. Unlike Anne, who had been born into a very comfortable upper-middle-class life, Carl had been born into a struggling working-class family. His father had been a railroad worker who worked such long hours he almost never saw his family. A union man, he lost his job when Carl was eight years old for participating in a failed strike demanding better working conditions. For months afterwards, the family ate almost nothing but beans. One of Carl’s dominant childhood experiences was of hunger – in the deep, psychological sense of not knowing when you would be able to get food to relieve it. For Carl, hunger meant growing up early. He became deeply aware of injustice… of the fact that many people, like his family, worked hard and still had nothing, and yet were harshly judged as poor White trash by families exactly like Anne’s. Carl joined gangs and learned to fight when he was very young. Like so many others, he also learned to drink and smoke to alleviate the pain of having ones dignity ripped away. He would continue to drink, smoke, and fight until World War II, when he decided to swear off it all to better commit himself to his work as a journalist and labor organizer.

Carl had been a very thoughtful child – a voracious reader who spent hours listening to the conversations of his large extended family, who often gathered around the kitchen table for discussion. Carl’s father was an agnostic socialist who had named his son after Karl Marx; whereas his mother and her extended family were all devout Catholics. Carl’s father was not anti-religious, but believed that matters of the afterlife and questions about God were beyond the human capacity to understand. He stayed quiet when conversations turned towards religion, but often mentioned at the end of religious conversations that Jesus’s teachings seemed right in alignment with socialism to him. The young Carl agreed with his father. They were all talking about loving thy neighbor, about the brotherhood and sisterhood of humankind that his future wife Anne had also been drawn to as a child. Carl’s heroes, growing up, were Christian saints on the one hand, and socialist leaders on the other. To him, they seemed to hold the same ideals.

When Carl was not out roaming around with his gang getting into fights, he was at home absorbed in books. His parents had only gone to elementary school, and they pushed their children to do well in school so they could have a better life than them. Carl went to a Catholic school, and when he was thirteen the nuns encouraged him to put his intellectual abilities in the service of God and to begin studying to become a priest. Carl accepted this as an honor that would help him fulfill his young desire to live a life of social responsibility. However, by the time he was sixteen, he found himself rebelling against the church, and soon dropped out of school entirely. He had not turned against the church’s teachings, however, but was rather rebelling against the structures of authority within his church, school, family, and ultimately, society. Looking for work as a young, rebellious, working-class intellectual, Carl gravitated towards journalism, just as Anne would later do. He was given the task of reporting on the police department, where he witnessed incredible corruption and brutality. Eight years older than his future wife Anne, Carl was soon reporting on the Great Depression, including the intense labor struggles of local impoverished coal miners… all while still a teenager. The combination of his upbringing and the things he witnessed as a reporter led him to become a devoted labor organizer.

When Anne was first introduced to Carl, he was covering labor issues for the newspaper, while she was covering education. However, from time to time, Anne would help Carl on his labor reporting. When she showed interest in the subject, he began giving her books to read on socialism and the history of labor organizing. She was soon attending union meetings with him. Anne had been raised to believe that people like her family were well off because they were smart, disciplined, and hard working, and that if people were poor it meant they had made bad decisions or were lazy. Anne had long doubted these class prejudices, and understanding the history of labor organizing – and getting to know the organizers themselves – destroyed them completely. She came to see the working class as another exploited group suffering from negative stereotypes, who, like African American freedom fighters, were dignified, intelligent, and fighting hard for the right to live a decent life. Carl helped Anne commit herself to ending class oppression, and she helped him commit himself to the battle against White supremacy....

Anne Braden was thrown into infamy, however, before she had a chance to embrace the work she would one day be most remembered for. In March of 1954, a Black World War II veteran named Andrew Wade approached the Bradens for help. Wade had been trying to purchase a home outside of the segregated Black communities of Louisville – he simply wanted a nicer, larger home for his growing family than was available in Black neighborhoods. Wade had a successful business, and came close to closing a deal on a few houses… but as soon as he met the real estate agents and they saw that he was Black, he was rejected. Wade asked some of his White friends if they would be willing to purchase the house under their name, and then transfer it to him. They refused. Wade then approached the Bradens. He did not know them personally, but they had developed a reputation for supporting Black causes by that time. They did not hesitate to support him....

The Braden’s were soon receiving a continuous stream of death threats: the phone rang every five or ten minutes; and because the Bradens were worried about the Wades, they felt compelled to pick up each and every call. Anne, however, noticed a pattern in the threatening voices, and realized that it was likely only half a dozen people calling on rotations, hoping that if each of them only called once an hour, their voice would not be recognized. This decreased her stress, but then a call came in saying that “something” would happen today. And then: in six hours. Five. Four. Three. Two. One. The calls kept coming. Fifteen minutes. Carl was unfazed, staying focused on his reading in the living room. He said that if they were really going to be attacked they wouldn’t be warned. Anne later reflected that Carl had long ago learned to shrug off physical threats. But it was her first time confronting them. She took the kids and left the house in case a bomb had been planted...

Shortly after the bombing, Anne appeared in court to serve as a witness in the investigation that was taking place. When she was called to the stand, she expected to be questioned about the threats to her family. Did she know who made them? Did she have any insights into who might have been involved in the bombing? Anne, however, was not asked these questions. Instead, she was grilled on her political beliefs. Had she been a member of any “subversive” organizations? Did she associate with Communists? What kind of literature did she read? Anne found herself at the center of a highly publicized, anti-Communist witch-hunt during one of the most politically repressive periods in U.S. history: McCarthyism.

During the period of McCarthyism, right-wing forces exploited the growing tensions between the Soviet Union and the United States that developed in the wake of the Second World War. They used those tensions to whip the American public into a state of fear: Communism, they said, would spread rapidly across the globe unless severe measures were taken. They warned that Communists had already infiltrated deep into American society, and were working with the Soviet Union to undermine the United States from the inside. After using this wildly unsubstantiated myth to whip the public into a state of fear, these forces then used that fear as an excuse to destroy causes they opposed – including civil rights and organized labor – under the pretense that such causes were Communistic. It was easy to manufacture the connection because Communists were, indeed, major supporters of racial justice and labor rights. Because Communists were highly involved in those causes, anyone devoted to those causes would have worked around and known Communists themselves. In the period of McCarthyism, anyone who was around Communists was framed as a Communist sympathizer, which was then equated with being an enemy of the state. This is what was now happening to Anne and Carl Braden.

(3) The New York Times (14th December, 1954)

Carl Braden, a newspaper man, tonight was convicted of advocating sedition. His punishment was fixed at fifteen years' imprisonment and a $5,000 fine.

After the criminal court jury handed down its verdict, the 40-year-old defendant was jailed immediately. Under Kentucky law, the jury fixes both the verdict and the penalty but both can be rejected by the judge...

After Braden's employment by the Courier-Journal has come to an end with his conviction. "This newspaper has gone on the time-honored principles, rooted in our American Constitution, that a man is innocent until proved guilty. Since Braden was charged by the grand jury on October 1st, he has performed no work for this organization. His conviction now puts a permanent end to his connection with the Courier-Journal."

Braden a copy editor, had been on leave with pay pending outcome of the case against him.

The newspaper man, his wife, Anne, 30, and four other white persons were indicted for advocating sedition following an explosion at the home of a Negro last June.

Braden had purchased the house in an all-white neighborhood, then transferred it to Andrew Wade, a Negro electrical contractor.

The Bradens and three other persons were accused in a second indictment of stirring up racial strife to promote communism. The state contended the dynamiting was a Communist plot to excite racial hatred. Ending its case on the thirteenth day of the trial, the Commonwealth told the jury it had a simple issue before it: "Sedition is communism and communism is sedition - there is no distinction."

The defence on the other hand, argued that the prosecution was trying to get the jury to "say something the law doesn't say". Braden's attorney said the issue was simply "whether or not a man has the right to an opinion different from those in the community."

(4) Rick Howlett, Remembering the Wades, the Bradens and the Struggle for Racial Integration in Louisville (1st December, 2014)

This year, many in Louisville have been marking the anniversary of a touchstone event of the Civil Rights era.

It started 60 years ago when white activists, led by Carl and Anne Braden purchased a home on behalf of a young black family

That act touched off weeks of racial violence and led to serious criminal charges against the activists.

Today, the neighborhood in Shively seems a most unlikely place for cross-burnings, gunfire and a dynamite attack, but that’s exactly what happened along the street over the course of several weeks in 1954.

The hostility began when an African-American family - Andrew Wade, his pregnant wife, Charlotte and their 2-year-old daughter Rosemary - moved into their new home at 4010 Rone Court.

Andrew Wade was an electrician who wanted to move his family to the suburbs but was turned down by a succession of white real estate agents, who refused to cross the illegal but still highly observed line of segregation.

In an interview from the 1980s featured in the documentary Anne Braden: Southern Patriot, Wade recalls a piece of advice he received from agent.

“He said ‘Wade, let’s be realistic - if you see a house, you like the house, regardless of where it is, get a white person if necessary if it’s in a white neighborhood to buy the house for you and transfer it to you. It’s that simple.'”

So, that’s what he did. Wade enlisted the help of acquaintances Carl and Anne Braden, left-wing activists who had been vocal in their opposition to Louisville’s housing segregation laws..

The transaction was completed but trouble began as soon as the Wades moved in.

“That night, they heard gunshots, and somebody was firing at the house, and Andrew says he told his wife to get down, but it didn’t hit anybody. And they looked out and there was a cross burning in the field next to them,” Anne Braden recalled in the documentary.

There would more trouble in the days to come; a stone bearing a racial epithet hurled into a window, the local dairy refused to deliver milk; the Wades’ newspaper subscription canceled because the carrier wouldn’t deliver it.

Police were stationed nearby for protection, but the Wades and their white allies didn’t trust them, so they formed a committee whose members would take turns staying in the house.

One of the guards was Lewis Lubka. “I was in the back kitchen with a gun. And when we were shot at we shot back. I was working days and helping guard the house at nights,” said Lubka, the last surviving activist who’s now 88 and lives in Fargo, North Dakota.

Several weeks went by and tensions seemed to ease a bit. But just after midnight on June 27, 1954: “We was coming in and a bomb went off under the house,” Lubka said.

The home was blown up with dynamite. The explosives were placed under Rosemary’s room. No one was in the house at the time.

Cate Fosl is a biographer of Anne Braden and heads the Anne Braden Institute for Social Justice Research at the University of Louisville. She said it was no secret who was responsible for this and other attacks, but:

“No indictments were returned against any of the neighbors, even though they had admitted to burning a cross and being hostile to the idea. But all of the indictments were against the whites who supported the Wades in this quest for a house,” Fosl said.

Anne and Carl Braden and the five other whites were charged with sedition, accused of hatching a Communist plot to buy the home, blow it up, touch off a race war and overthrow the Commonwealth of Kentucky.

Today, it sounds outrageous. But in an interview from the collections of the Kentucky Historical Society, Anne Braden provided some context: this happened at the confluence of McCarthyism and the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling that outlawed school segregation.

“And I always felt that the Wades and us became lightning rods. They couldn’t get at the Supreme Court but that could get to us,” Anne Braden said.

Carl Braden was convicted of sedition and spent eight months in prison.

The following year a ruling came down from the U.S. Supreme Court in a Pennsylvania case that said, in essence, sedition is a federal crime, not a state offense.

Fosl said the Bradens and the Wades would be proud of how the once-troubled Shively neighborhood has changed.

“It is one of the most integrated, multi-racial, multi-cultural neighborhoods in Louisville today,” Fosl said.

It’s also the home of 31-year-old postal worker Steve Ebbs, his wife, and two young daughters.

On a October morning, Ebbs is standing next to a historical marker erected near the Wade home site a few years ago.

He’s the great-nephew of Andrew and Charlotte Wade, and lives down the street from 4010 Rone Court, now called Clyde Drive.

Ebbs has been the family’s spokesman during the anniversary commemorations.

“It’s something that I really take pride in,” Ebbs said.

“I’ve made sure that my children understand the significance of the fact that there’s a monument here and it is our blood relatives that went through what they did to receive something like this. So I make sure that I definitely give it the respect that it’s due.”

Carl Braden’s state conviction was later reversed and the charges against the other defendants were dropped.

Branded as Communist troublemakers, all the defendants had trouble finding work in the following years. Carl Braden died in 1975. Anne Braden continued her work opposing housing and school segregation.

The Wade family attempted to repair their home, but amid continuing hostility, sold the house at a loss and moved back into west Louisville, where Charlotte Wade still lives. She no longer speaks publicly about the case. Andrew Wade died in 2005.

Anne Braden, who died in 2006 at the age of 81, told the Kentucky Historical Society she had no regrets about helping the Wades buy their dream home.

“It would have been unthinkable for us to say no, because this is something we believed in. You live by what you believe in or you don’t, that’s all.”

(5) The Harvard Crimson (16th February, 1956)

A former Louisville newspaperman convicted of violating a Kentucky sedition law defended his actions before a sparse New Lecture Hall audience last night, claiming that the charges against him were subterfuge to punish him for selling a house in a white district to a Negro.

Released under $40,000 bail pending appeal on his December 13, 1954 conviction, Carl Braden asserted that the sedition charges against him was a "cover-up" for the dynamiting by white neighbors of the house he bought for a Negro friend.

In a hostile question period, Braden denied that he had ever been a member of the Communist party, and rejected the implication that the bombing had been part of a "Communist plot" to exploit the segregation issue. Law enforcement agencies in Louisville, he said, attempted to "cover up the bombing by instituting a witch-hunt."

Braden, a copy editor on the Louisville Courier-Journal from 1950 until five minutes after his conviction, brought the house for Andrew Wade IV, a Negro. He then transferred title to Wade, and a series of threats and cross-burnings ensued. Two months after Wade and his family moved into the home, it was dynamited. An indictment was obtained against a friend of Wade's charging that he blew the house up. This indictment has not been tried, but Braden was tried and convicted of sedition, on charges asserting that he brought the situation about to exploit the segregation issue.

Braden, now on a speaking tour with Wade, was optimistic about the future of the South. "I think we're going to end segregation there," he said. "We're going to change the political situation, too," he continued. "We're going to throw out all those stumblebums like Eastland." But he emphasized that the end of segregation in housing was a necessary prerequisite to solution of the South's other problems.

(6) Amber Duke, Faces of Liberty: Anne & Carl Braden (13th November, 2014)

"As long as I have life and strength, I hope to be on the barricades of that struggle [for justice]. I hope and trust the ACLU will be there too.” - Anne Braden, 1990

A history of the struggle for civil rights in Kentucky would not be complete without Anne and Carl Braden. In 1954, before a Kentucky branch of the ACLU existed, the couple (who had already taken action as union and desegregation activists) decided to help the Wades, an African American family, buy a house in an otherwise all-white neighborhood in the Shively neighborhood of Louisville.. The Wades had reached out to the Bradens to purchase the home on their behalf after several real estate deals had fallen through when the Wades’ race was discovered. The Wades moved into their new home, only to face violence and exclusion from their white neighbors–including a burning cross and eventually a bombing.

After the bombing, the Bradens, along with a small group of activists, were charged with sedition and taken to court at a time when officials were caught up with McCarthyism and anti-Communist hysteria. Carl spent months in jail on a sedition conviction before being released on a bond. The Bradens’ sedition charges epitomize the way that McCarthyism was used to restrict Kentuckians’ free speech rights in the 1950s–and why the ACLU-KY was founded in 1955.

The Bradens were not deterred from their passion for activism: they continued to speak out, especially against racism. The couple were again charged with sedition in 1967 as a result of their opposition to strip mining.

But, as Anne wrote, “these were different times.” She described how the court atmosphere had changed in the 13 years since 1954: “When the sheriff brought us to Lexington from the Pike County jail for the hearing, we walked into a courtroom filled not with our enemies but our friends - activists from the University of Kentucky student movement. When the prosecutor asked me, ‘Are you or have you ever been...,’ the courtroom burst into laughter. . . . I then knew that the 1950s were finally over.”

After Carl died in 1975, Anne Braden continued her civil rights and anti-racism activism, working off and on with, and sometime against, the ACLU-KY for decades until her death in 2006. Anne was the first recipient of the national ACLU's Roger Baldwin Medal of Liberty, which is perhaps second only to the Presidential Medal of Freedom as a high honor in the country for people dedicated to defending the Constitution and Bill of Rights.

(7) David J. Leonard, Anne Braden: Defiant, Inspiring, and Self-Aware (23rd January, 2013)

Emblematic of a generation of men and women in the South that challenged their parents’ generation’s views on race, jobs, gender, sexuality, and a broader sense of the world, Anne Braden did more than look backwards. She, like Bayard Rustin, was a woman “ahead of her times, yet the times didn’t know it.” Anne Braden: Southern Patriot, a documentary from California Newsreel, highlights how she did not merely respond to the regressive and oppressive realities of the South, but instead looked forward toward a more just and equal society.

Like Ella Baker, Braden was committed to and involved in a myriad of movements, fighting against economic injustice, environmental injustice, war, classism, racism, and sexism. Where there was violence and degradation, Anne Braden was likely fighting alongside countless others. The film highlights not only her work, but her ethics and ethos, a willingness to confront injustice whereever it confronted her. Through the film, Braden expresses a level of fearlessness that spit in the face of white supremacy, patriarchy, and class inequality. She was always standing in opposition to white supremacy, on the other side of the police state, yet the danger and the consequences never led her to shy away from a fight.

What Anne Braden’s life reveals, and what Anne Braden: Southern Patriot demonstrates in vivid detail, is how her work was both an external fight and an ongoing reconciliation with her own whiteness. Her fight was with her own privileges and their relationship to a broader system of white supremacy. In a powerful moment in the film, Braden recounts a moment of clarity where she felt the impact of American racism in her own ethos and worldview as much as with those “backwards neighbors”:

In the mornings before I came downtown I would call the courthouse, to see if anything big happened overnight, because if there had I’d have to skip breakfast usually and go on to the courthouse and get the details and get it into the first edition of the afternoon paper. When I would get downtown I often stopped for breakfast and met a friend there. And the waitress was putting our food down on the table. And so he said anything doing? And I said no, just a colored murder. And I don’t think I’d have ever thought anything about it if that black waitress hadn’t been standing there. She was pouring coffee into our cups and her hand was sort of shaking, but there wasn’t an expression on her face. It was like she had a mask. And my first impulse was that I wanted to get up and go put my arms around her and say, “Oh I’m sorry. I didn’t mean that. It’s not that I don’t think the life of your people is important. It’s my newspaper that says what news is.” And then I just suddenly realized I had meant exactly what I’d said.

Listening to these words, and others from Braden, I was struck by the resonance within our own moment. The silence afforded to Chicago compared to Sandy Hook, for example, and the erasure of anti-black state violence and mass incarceration from public discourse highlight how Braden’s assessment still matters 40 years later. Her diagnosis of society, and every white member of society, remains an unfortunate reality and this is why her life’s work deserves attention.

Throughout her life, Anne Braden’s fight was not just with white supremacy, but also most importantly with white America. In actions and words, she challenged white America to make a choice, to decide whether or not to challenge racism, whether or not to accept the unearned benefits of American racism:

“What you win in the immediate battles is little compared to the effort you put into it but if you see that as a part of this total movement to build a new world, you know what could be. You do have a choice. You don’t have to be a part of the world of the lynchers. You can join the other America. There is another America!”

In a powerful letter she lays out the history of white supremacy, state violence, and the complicity of white women. She addresses patriarchy, and how white domesticity operates in relationship to white racism, and the demonization of black male sexuality.: