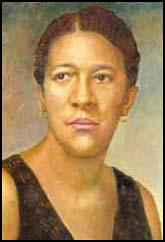

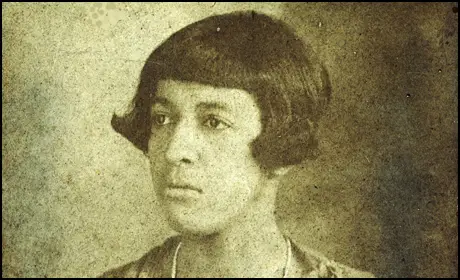

Modjeska Simkins

Modjeska Monteith was born on 5th December, 1899. She attended Benedict College, South Carolina and after graduating in 1921 became a schoolteacher at the Booker T. Washington School in Columbia. When she married Andrew Simkins, a prosperous African American businessman, she was forced to resign as the local public school system did not allow married women to teach.

In 1931 Simkins found employment with the South Carolina Tuberculosis Association. Her role was to raise funds and assist in health education among African Americans. Shocked by the poverty she witnessed, Simkins became more concerned with politics and joined the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP).

Simkins established clinics for tuberculosis testing at churches, schools and cotton mills. She also published a newsletter and arranged for annual meetings with other African American leaders. The South Carolina Tuberculosis Association became concerned about her political activities and in 1941 she was told that she would have to leave the NAACP. When Simkins refused she was fired.

A popular lecturer on civil rights, in 1942 Simkins was appointed secretary of the South Carolina Conference of the NAACP. In this post she undertook lawsuits on behalf of African Americans. Her campaign to force South Carolina to remove racial differences in teachers salaries achieved success in 1944. Simkins next campaign was to persuade the South Carolina Democratic Party to reform its voting system.

In December, 1947, Simkins was one of the fifty-one African American leaders who urged Henry Wallace to run for president as the Progressive Party candidate. The following year Simkins played a prominent role in Wallace's failed attempt to become president. She was also active in the campaign to persuade Congress to pass an Anti-Lynching bill.

After the war Simkins supported her friends, Benjamin Davis, Paul Robeson and Eslanda Goode in their struggle with the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). In July, 1948, Davis and ten other leaders of the American Communist Party was charged with violating the Alien Registration Act. This act made it illegal for anyone in the United States to advocate, abet, or teach the desirability of overthrowing the government. In October, 1949, after a nine-month trial, Davis was found guilty of violating the act. He was sentenced to five years in prison and a $10,000 fine.

In 1949 Simkins began her campaign to end segregation in public schools. Her efforts resulted in the Supreme Court ruling in 1952 that separate schools were acceptable as long as they were "separate and equal". It was not too difficult for the NAACP to provide information to show that black and white schools in the South were not equal. In 1954 the Supreme Court announced that separate schools were not equal and ruled that they were therefore unconstitutional.

In November, 1957, Simkins was removed as state secretary of the NAACP. The main reason for this was that some people objected to Simkins close relationship with the American Communist Party. Although she never joined the party, she was willing to work with its members and had been vocal in her support of those blacklisted during the McCarthy Era.

Simkins continued to campaign for desegregation and in 1963 helped her niece to become the first African American student since reconstruction to enter the University of South Carolina.

Modjeska Monteith Simkins died in 1992.

Primary Sources

(1) Katherine Allen, Advocate for the People: Modjeska Monteith Simkins (5th December, 2019)

On May 17, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka struck down racial segregation in schools. For Modjeska Monteith Simkins, who co-authored the petition that became Briggs v. Elliott, one of the five cases that comprised the Brown decision, the Supreme Court's ruling was far from either the beginning or the end of a lifetime spent fighting for human rights. Over the course of her 92 years, she displayed a courage and perseverance that many argue was unmatched.

Modjeska Monteith was born in Columbia, S.C. on December 5, 1899. After graduating from Benedict College she taught at the segregated Booker T. Washington High School but was forced to resign after marrying Andrew W. Simkins in 1929. Rather than stay at home, she became the first Director of Negro Work for the South Carolina Tuberculosis Association, where she witnessed the stark disparities in treatment and health education for black and white South Carolinians.

Her time with the SCTA positioned her as an authority on the issues African Americans faced in South Carolina - namely discrimination in the form of unequal and even denied access to education, healthcare, economic opportunities, and the ballot. Simkins, in this instance and throughout her life, chose action over inaction and moral anger over despair.

By 1941, Simkins moved to organize African American resistance on a broad scale. That year she became the secretary of the South Carolina NAACP State Conference of Branches. Simkins also convinced budding activist and newspaper publisher John H. McCray to move his Charleston Lighthouse newspaper to Columbia, a move she and her husband helped finance. The merger of McCray's paper and the Sumter Informer in 1941 marked the emergence of a black press that continually advocated action over appeasement, helped mobilize support for NAACP efforts, and kept citizens informed of ongoing injustices in communities across the state.

Firmly established in the leadership of the NAACP, Simkins joined with other activists to challenge South Carolina's continued flouting of established law. Key cases included the fight for equal pay for black teachers, the fight to end the all-white Democratic primary in South Carolina, the fight to end segregation in intrastate transportation, and the fight to end segregation in public schools, in Briggs v. Elliott. Thurgood Marshall argued the latter, and often stayed with Simkins while in South Carolina prepping for this trial and others.

Rarely told as part of this story is the reaction of white citizens against South Carolina communities and individuals fighting for these rights. Columbian George Elmore lost his business and home. The petitioners in Briggs v. Elliott faced "economic terrorism" and actual acts of terror - Rev. Delaine's home and church were burned, and he later fled South Carolina, never to return. John H. McCray spent two months on a chain gang after being convicted of libel in 1950 in the lead up to the Brown v. Board decision. Here again, Simkins emerged relatively unscathed, and her family's stake in Victory Savings Bank allowed Simkins to provide financial assistance to others in the movement. Simkins' husband maintained a diversified real estate portfolio in Columbia that catered to African Americans, and she later operated Motel Simbeth, which appeared in The Negro Traveler's Green Book. Simkins relationship with SNYC and other left-wing groups with rumored ties to the Communist Party led to her name appearing in memos to the House Un-American Activities Committee.

In 1955 she founded and led the Richland County Citizens Committee, which advocated for the desegregation of the state hospital and against all levels of corruption in what she always called "the power structure." In campaign materials created for an unsuccessful run for Columbia City Council in 1983, she called out the status quo of race and gender relations, contending that "over one-half of all Columbians are women and over one-third of them are black, yet Columbia's political decisions have always been made by white men." For all her contributions, Simkins only received broad recognition of her work towards the end of her life, although today she is often considered South Carolina's foremost human rights activist.